Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium replicates in macrophages, where it is subjected to antimicrobial substances, including superoxide, antimicrobial peptides, and proteases. The bacterium produces two periplasmic superoxide dismutases, SodCI and SodCII. Although both are expressed during infection, only SodCI contributes to virulence in the mouse by combating phagocytic superoxide. The differential contribution to virulence is at least partially due to inherent differences in the SodCI and SodCII proteins that are independent of enzymatic activity. SodCII is protease sensitive, and like other periplasmic proteins, it is released by osmotic shock. In contrast, SodCI is protease resistant and is retained within the periplasm after osmotic shock, a phenomenon that we term “tethering.” We hypothesize that in the macrophage, antimicrobial peptides transiently disrupt the outer membrane. SodCII is released and/or phagocytic proteases gain access to the periplasm, and SodCII is degraded. SodCI is tethered within the periplasm and is protease resistant, thereby remaining to combat superoxide. Here we test aspects of this model. SodCII was released by the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B or a mouse macrophage antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP), while SodCI remained tethered within the periplasm. A Salmonella pmrA constitutive mutant no longer released SodCII in vitro. Moreover, in the constitutive pmrA background, SodCII could contribute to survival of Salmonella during infection. SodCII also provided a virulence benefit in mice genetically defective in production of CRAMP. Thus, consistent with our model, protecting the outer membrane against antimicrobial peptides allows SodCII to contribute to virulence in vivo. These data also suggest direct in vivo cooperative interactions between macrophage antimicrobial effectors.

Survival in macrophages is essential for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence (26, 36). In the phagosome, Salmonella is challenged with a plethora of antimicrobial substances, including superoxide, produced by NADPH oxidase, cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs), which disrupt bacterial membranes, and phagocytic proteases (7, 35). These oxidative and nonoxidative effectors act to inhibit or kill invading bacteria (38), but direct mechanistic interactions among these effectors in vivo are largely speculative.

Salmonella resistance to the oxidative burst of phagocytes requires periplasmic Cu/Zn-cofactored superoxide dismutase (SodC) (5). Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain 14028 produces two periplasmic superoxide dismutases. SodCII is chromosomally encoded, whereas SodCI is encoded on the fully functional Gifsy-2 bacteriophage (18). These two enzymes are 60% identical at the amino acid level. We and others have shown that only SodCI contributes to virulence during infection in the animal. In contrast, SodCII is not required during infection, even in the absence of SodCI (21). It is clear that SodCI specifically protects against phagocytic superoxide; there is no other role for the enzyme (5, 22).

Transcription of sodCI is controlled by PhoPQ and is induced ∼17-fold in bacteria recovered from cultured macrophages or mouse spleens (13). The sodCII gene is controlled by RpoS and is also induced ∼3- to 4-fold during infection of macrophages and mice (13). Although sodCI is more highly induced in the phagosome, differential gene expression cannot explain the disparity in their contributions to virulence: a strain containing SodCI expressed from the sodCII promoter was fully virulent, whereas SodCII expressed from the sodCI promoter did not contribute to virulence (21). Thus, both proteins are apparently made during infection, suggesting that some physical difference between the two proteins allows SodCI, but not SodCII, to effectively combat phagocytic superoxide.

SodCI is reported to have a 2.7-fold higher specific activity than that of SodCII (2). These two enzymes also differ in their affinities for Cu and Zn (2). Other differences have been noted as well (2). But it seems unlikely that subtle differences in enzymatic activity can completely explain the all-or-nothing phenotype observed during infection. Overproduction of SodCII from the sodCI promoter does not complement a sodCI null phenotype (21). Moreover, even if SodCII accounted for only a fraction of the activity, one would expect to see a phenotype conferred by loss of SodCII in a sodCI null background. Such a synthetic interaction is observed with mutations in the cytoplasmic SODs, which protect against endogenously generated superoxide (5).

We have sought other properties, beyond enzymatic activity per se, to explain the inability of SodCII to protect against phagocytic superoxide. From our work and that of others, we know that SodCI is dimeric and protease resistant (2, 22, 33). We have also discovered that SodCI is “tethered” within the periplasm by a noncovalent ionic interaction. In vitro, this is manifested as limited release by osmotic shock (21, 22). In contrast, SodCII is monomeric, protease sensitive, and released normally from the periplasm (22). We found that SodC from Brucella abortus, expressed from the sodCI locus, was able to complement sodCI, resulting in full virulence (22). This enzyme is monomeric and released by osmotic shock but is protease resistant, suggesting that the latter property is critical in the phagocyte (21, 22). However, in the phagosome, Salmonella is also subjected to antimicrobial peptides, which disrupt membranes, similar to an osmotic shock (45). Therefore, we believe that tethering might also contribute to the ability of SodCI to protect Salmonella from phagosomal killing.

Taking all these data into consideration, our current working model proposes that macrophages deliver a variety of antimicrobial substances to the Salmonella-containing phagosome. CAMPs at least transiently disrupt the outer membrane of the bacterium. Periplasmic proteins such as SodCII are released and/or phagocytic proteases gain access to the periplasm, and SodCII is degraded under these conditions. The presence of CAMPs and additional phagosomal conditions induce the PhoPQ regulon, which includes sodCI, leading to resistance to antimicrobial peptides (3, 13). SodCI is tethered within the periplasm and is inherently protease resistant. Therefore, it remains to detoxify the phagocytic superoxide. Here we provide evidence in support of this model.

Consistent with this model, Uzzau et al. (44) and Ammendola et al. (1) have noted that the steady-state level of SodCII protein is low in bacteria recovered from macrophages or animals, whereas SodCI levels are high. However, they have proposed that the low levels of SodCII are due to transcriptional downregulation in response to the host environment. Most recently, these investigators proposed that sodCII transcription was downregulated in response to the low Zn levels found in the macrophage phagosome, although no molecular mechanism was proposed (2). The experiments performed in this study distinguish between these two interpretations of the available data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and reagents.

Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl per liter), with 15 g of agar per liter added for solid medium. The concentrations of the antibiotics used were as follows: ampicillin and kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 25 μg/ml. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was purchased from Fisher, N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) was purchased from CalBiochem, and polymyxin sulfate B was purchased from Alexis. The 34-amino-acid mature cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) was synthesized by the Protein Facility Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Strain construction.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains used in this study are isogenic derivatives of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain 14028. Deletion of genes and concomitant insertion of antibiotic resistance cassettes were carried out using lambda Red-mediated recombination (6, 8). All constructs were confirmed by PCR analysis and transduced into an unmutagenized wild-type background, using phage P22 HT105/1 int-201 (24). In some cases, the antibiotic resistance cassette was recombined out of the chromosome by FLP, produced from the temperature-sensitive plasmid pCP20 (6). Transcriptional lac fusions were constructed by integrating fusion plasmids into FRT scar sites by FLP-mediated recombination as described previously (8).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotypea | Deletion or cloned endpointsb | Source or referencec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| 14028 | Wild type | ATCC | |

| JSG435 | pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam | 16 | |

| JSG1050 | pmrI::MudJ | 43 | |

| TN3740 | LT2 leu-485 trp-190::(lacI lacp T7 pol spc) | C. G. Miller | |

| JS531 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 | 1516586-1516598 | 13 |

| JS900 | Φ(sodCI+-6xhis-lac+)2920 | 1098178-1130040 | |

| JS901 | ΔhtrA::Kan | 244465-245933 | |

| JS902 | ΔkatE11::Cam | 1397114-1399406 | |

| JS903 | Δzur::Cam | 4461801-4462315 | |

| JS904 | ΔoppA-F::Cam | 1858868-1841314 | |

| JS905 | Φ(sodCI+-6xhis-lac+)2920 zyd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS906 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 zyd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS907 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 ΔhtrA::Kan zyd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS908 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 ΔrpoS1191::Tet | ||

| JS909 | Φ(katE-lac+)11 | ||

| JS910 | Φ(katE-lac+)11 ΔrpoS1191::Tet | ||

| JS911 | Φ(znuA-lac+) | ||

| JS912 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 ΔznuA::Cam | ||

| JS913 | Φ(katE-lac+)11 ΔznuA::Cam | ||

| JS914 | Φ(znuA-lac+) Δzur::Cam | ||

| JS915 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 Δzur::Cam | ||

| JS916 | ΔsodCI-104::Cam ΔsodCII-103::Kan/pMC101 | ||

| JS917 | ΔsodCI-104::Cam ΔsodCII-103::Kan/pMC102 | ||

| JS918 | ΔznuA::Cam | 1986415-1987359 | |

| JS921 | ΔoppA-F::Cam trp190::(lacI lacp T7 pol spc) ΔsodA101 ΔsodB102 ΔsodCI-104 ΔsodCII-103/pBK103 | ||

| JS922 | ΔsodA101 ΔsodB 102 ΔsodCI::Tet ΔsodCII-105::Cam/pMC102 | ||

| JS923 | ΔphoN::Kan/pBK104 | ||

| JS924 | ΔsodA101 ΔsodB102 ΔsodCI::Tet ΔsodCII-105::Cam/pMC101 | ||

| JS925 | ΔsodA101 ΔsodB102 ΔsodCI::Tet ΔsodCII-105::Cam/pRK106 | ||

| JS926 | zjd::Tn10d-Cam/pMC101 | ||

| JS927 | pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam/pMC101 | ||

| JS928 | pmrI::MudJ | ||

| JS929 | pmrI::MudJ pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS930 | Φ(sodCII+-lac+)110 pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS931 | ΔsodCI-104::Kan zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS932 | ΔsodCI-104::Kan sodCII-106::Tet zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS933 | ΔsodCI-104::Kan pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS934 | ΔsodCI-104::Kan ΔsodCII-106::Tet pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-Cam | ||

| JS935 | ΔsodCII-103::Kan | ||

| JS936 | ΔsodCI-104::Cam ΔsodCII-103::Kan | ||

| Plasmids | |||

| pBK103 | pET21b sodCI-6xhis | 1130056-1130586 | |

| pMC101 | pWKS30 sodCI | 21 | |

| pMC102 | pWSK29 sodCII | 21 | |

| pRK106 | pWKS30 sodCI Y87E Y109E | 22 | |

| pBK104 | pWSK30 phoA-6xhis | ||

| pKD46 | 6 | ||

| pCP20 | 6 | ||

| pKG136 | 8 |

All Salmonella strains are isogenic derivatives of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain 14028.

Numbers indicate the base pairs that are deleted or cloned (inclusive), as defined in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 genome sequence (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

This study unless specified otherwise. ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

A phoA-6×His allele was constructed by including a sequence encoding a 6×His tag in the 3′ PCR primer (CGC GGA TCC TTA CTA GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG TTT CAG CCC CAG AGC G) and amplifying the phoA gene from the Escherichia coli chromosome (with 5′ primer TTG TAC ATG AAG CTT ATA AAG TGA AAC AAA). The resulting PCR product contained a HindIII site 5′ of the phoA open reading frame (ORF), which was in frame with the 6×His sequence, followed by a stop codon and a BamHI site on the 3′ end. This fragment was cloned into pWKS30 (47). The resulting plasmid was introduced into a phoN deletion strain. The sodCI gene was amplified using primers (5′ primer, CGA GGT AAC ATA TGA AAT ACA C; and 3′ primer, TTG CTC GAG TTT CTC AAT GAC AC) that introduced an NdeI site at the start codon and an AvaI site at the 3′ end, replacing the stop codon. This fragment was cloned into the pET21b plasmid, resulting in the sodCI ORF being in frame with 6×His-encoding sequences at the 3′ end. This plasmid was introduced into an otherwise sod null strain that produced the T7 polymerase under the control of LacI (JS921). Therefore, SodCI-6×His was produced upon the addition of IPTG.

The chromosomal sodCI-6×His allele was constructed by incorporating sequences encoding 6×His into the 5′ primer (TGG TGG CGG TGC ACG TTT TGC CTG TGG TGT CAT TGA GAA ACA CCA CCA CCA CCA CCA CTA GTA AGT GTA GGC TGG AGC TGC TTC G) used to amplify (with 3′ primer CTT TAG GGT CGA GCG CAT TTC GTG CCC CAT ATA TGA ATA TCC TCC) a Kanr cassette from plasmid pKD3 (6). This cassette was integrated downstream of the sodCI open reading frame via lambda Red-mediated recombination, such that the 6×His-encoding sequence was in frame with sodCI. The associated deletion extends through the left attachment site of the Gifsy-2 phage, which prevents phage induction or amplification (13).

Antibody production and Western blot analysis.

A peptide corresponding to the N-terminal 20 amino acids of mature SodCII was synthesized and used to raise antibody in a rabbit by Proteintech Group. Anti-His monoclonal antibody was purchased from Abcam, anti-β-galactosidase antibody was purchased from Zymed, and anti-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (anti-CAT) rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Zymed) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Abcam) was used as secondary antibody. Protein samples were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The proteins were transferred to Hybond-ECL membranes (Amersham). The appropriate region of the membrane was excised and exposed to the indicated primary and secondary antibodies. The Western blot procedure and the detection of HRP-conjugated antibodies with a chemiluminescence system were done according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham). Control experiments (not shown) with appropriate deletion mutants confirmed the specificity of the various antibodies and the identities of the bands in our Western analyses.

Immunodetection in bacteria recovered from infected macrophages.

RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; HyClone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% l-glutamine (BioWhittaker). Macrophages were seeded into six-well plates at 1 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells/well. The sodCI+-6xhis-lacZ+ and sodCII+-lacZ+ fusion strains were grown for 16 h in LB with aeration. Bacterial cells were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). An aliquot was frozen at −20°C; this was considered the LB sample. An aliquot of remaining bacterial cells was opsonized in 50% mouse serum for 30 min at 37°C. Bacteria were then diluted in DMEM and used to infect macrophages at a multiplicity of infection of ∼10. After 30 min of incubation, the wells were washed three times with PBS, and then DMEM containing 12.5 μg of gentamicin/ml was added to the wells to kill extracellular bacteria. After 20 min of additional incubation, the wells were washed once with PBS. DMEM with 12.5 μg of gentamicin/ml was added to the wells, and this was designated time zero. After 16 h, the wells were washed three times with PBS and macrophages were lysed with 1% Triton X-100. The released bacteria were washed with sterile distilled water and suspended in PBS. The number of bacteria in each sample was determined by plating dilutions of the sample. The remaining samples were frozen at −20°C. Based on the number of viable cells recovered, equal numbers (∼106) of recovered bacteria and bacteria from the original LB culture were boiled in loading buffer, and immunodetection was performed as described above.

Immunodetection in bacteria recovered from infected mouse spleens.

The sodCI+-6xhis-lacZ+ and sodCII+-lacZ+ fusion strains were grown in LB with aeration for 16 h. An aliquot was frozen at −20°C (the LB sample). Cells were diluted in sterile 0.15 M NaCl to ∼5,000 CFU/ml. An aliquot was diluted and plated to determine the actual number of cells. For each strain, two BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with ∼1,000 cells. Bacterial cells were extracted from splenic tissue as described previously (40). In short, after 4 days of infection, the two mice were sacrificed, and the spleens were recovered and homogenized together in PBS. The samples were centrifuged, and to release the bacteria, the pellets were suspended in sterile deionized water containing 40 units bovine DNase (Sigma). The bacteria were recovered by centrifugation and suspended in PBS. Serial dilutions of each suspension were plated on LB agar to determine the number of viable bacteria. The remaining samples were frozen at −20°C. Based on the number of viable cells recovered, equal numbers (∼106) of recovered bacteria and bacteria from the original LB culture were boiled in loading buffer, and immunodetection was performed as described above.

Enzyme assays.

Cyanide-sensitive SOD activity was determined using the xanthine oxidase-cytochrome c method (27). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was assayed as described previously (19). The total protein concentration of each extract was measured using a Coomassie blue dye-based assay from Pierce.

In most cases, SodC activity was determined in strains that are otherwise sod nulls and in which cyanide-resistant SOD activity, which we routinely measure, is negligible. To measure the effects of the chelators EDTA and TPEN on SodC activity, SodCI- or SodCII-expressing plasmids were introduced into a ΔsodCI ΔsodCII strain. This strain still produces cytoplasmic SodA and SodB. It is known that chelators can inhibit growth of sodA sodB mutants (25). The strains were grown for 16 h in LB and the indicated amount of EDTA or TPEN with aeration. These strains grew well under all of these conditions. Cyanide-resistant SOD activity (SodA and SodB) was subtracted from total SOD activity to yield the activity contributed by SodCI or SodCII.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed using a microtiter plate assay as previously described (41). In most cases, cultures were grown for 16 h in LB with aeration. For experiments examining the effects of EDTA and TPEN, cells were grown in 250 μl of LB in a 96-well plate while shaking at 37°C in an ELX808IU microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments). This allowed us to easily monitor growth under these conditions. β-Galactosidase units are defined as (μmol of ONP formed min−1) × 106/(OD600 × ml of cell suspension), where ONP is ortho-nitrophenol and OD600 is the optical density at 600 nm, and are reported as means ± standard deviations (n = 4).

Preparation of cellular fractions released by antimicrobial peptide or osmotic shock.

Cells were grown in 20 ml of LB with aeration for 16 h. For whole-cell lysates, 10 ml of culture was centrifuged and cells were suspended in 1 ml PBS. The cells were disrupted in a French pressure cell, and the resulting lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were used for Western analysis or to determine SodC activity. “Osmotic shockates” were obtained as described previously (21). In short, 10 ml of the same cultures was centrifuged, and the cells were suspended in 5 ml 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 0.5 mM EDTA. Samples were centrifuged again, and cell pellets were suspended in 2 ml plasmolysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 2.5 mM EDTA, 20% [wt/vol] sucrose, pH 7.4). After sitting at room temperature for 10 min, the cells were centrifuged, suspended in 1 ml ice-cold double-distilled water (ddH2O), and incubated on ice for 15 min. The cells were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was considered the osmotic shockate.

To obtain cationic antimicrobial peptide-released fractions, 20-ml aliquots of late-exponential-phase culture were washed and suspended in 1 ml of PBS. One sample was disrupted in a French pressure cell, and the resulting lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were used for Western analysis or to determine SodC activity (whole-cell extract; considered 100%). The remaining samples were treated with the indicated amount of polymyxin B or CRAMP antimicrobial peptide. After 20 min of incubation at 37°C, cells were spun down at 15,000 × g and supernatants were filtered (0.22-μm low-protein-binding filter; Millipore). The supernatants were used for Western analysis or to measure the amount of Sod activity released by antimicrobial peptide. In control experiments, the viability of cells before and after treatment was determined by plating dilutions of samples. Also, whole-cell extract and antimicrobial peptide-released fractions were assayed for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity.

Mouse competition assays.

For each competition assay, the two indicated strains were grown in LB for 16 h, mixed 1:1, and then diluted in sterile 0.15 M NaCl to 5,000 CFU/ml. Groups of 5 to 11 female BALB/c mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc.) or congenic Cnlp−/− mice (CRAMP− on a BALB/c background [34]) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.2 ml of inoculum (approximately 1,000 total bacteria). Inocula were plated on LB and then replica plated onto the appropriate selective medium to determine the actual number and percentage of each strain used for the infection. The animals were sacrificed after 4 days of infection. The spleens were harvested and homogenized, and dilutions were plated on LB agar. Colonies were replica plated onto selective medium to determine the percentage of each strain recovered. A competitive index was calculated as follows: (percent strain A recovered/percent strain B recovered)/(percent strain A inoculated/percent strain B inoculated). Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. In most cases, the strains were rebuilt by phage P22-mediated transduction, and the mouse virulence assay was repeated to confirm that the phenotype was the result of the designated mutation.

All animal work was reviewed and approved by either the University of Illinois IACUC (performed under protocol 07070) or The Ohio State University IACUC (performed under protocol 2009A0057).

RESULTS

SodCII is decreased posttranscriptionally in macrophages and mice.

We hypothesized that SodCII is subject to proteolysis in the macrophage, accounting for decreased protein levels despite induced gene expression (22). Other investigators have attributed low SodCII protein levels to transcriptional downregulation (2, 10). To explicitly distinguish these two models, we investigated SodCI and SodCII protein levels in bacteria recovered from RAW 264.7 macrophage cells or spleens of infected mice. We used transcriptional lacZ fusions in which the reporter gene was inserted immediately after the sodCI or sodCII stop codon (13). Thus, we could simultaneously monitor the steady-state levels of SodC (I or II) and β-galactosidase by Western analysis. The strains also contained a cassette encoding CAT, which we monitored to ensure equal loading of gels. In the case of SodCII, the primary antibody used was raised against a peptide corresponding to the first 20 amino acids of the mature protein, and the construct encoded wild-type protein. The SodCI construct contained a C-terminal six-His tag, and protein levels were monitored using an anti-His-tag monoclonal antibody. The SodCI fusion construct was also associated with a deletion from the 3′ end of the sodCI open reading frame through the left attachment site of the Gifsy-2 phage, thereby preventing phage induction or amplification, which could interfere with our assays (13). SodCI-6×His retains full enzymatic activity, and strains encoding this sodCI-6xhis transcriptional lacZ fusion are fully virulent (data not shown).

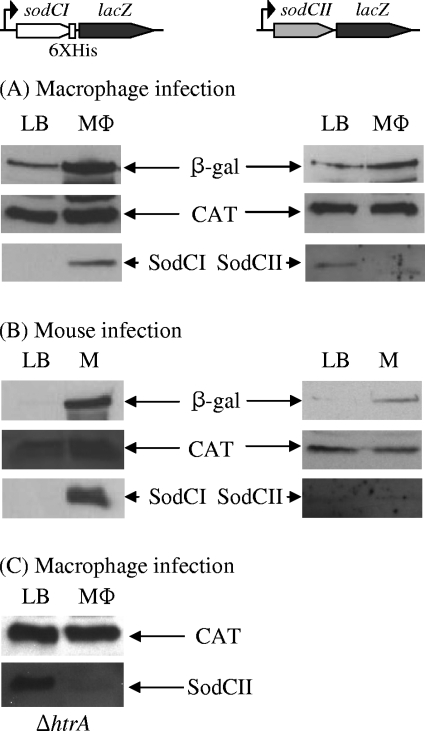

These strains were used to infect both tissue culture macrophages and mice. Bacteria were recovered from tissue culture cells 16 h after infection. In the mouse infections, bacteria were recovered from spleens after 4 days, using a previously described procedure (40). In each case, the number of viable cells recovered was determined by plating for CFU. Control cultures were grown for 16 h in LB. Equal numbers of viable cells were loaded onto gels, and separated proteins were blotted to nitrocellulose. The molecular weights of β-galactosidase, CAT, and SodC (I or II) differ enough that the corresponding region of each blot could be cut out and probed for the respective protein. Figure 1A and B show that the steady-state levels of both SodCI protein and β-galactosidase were significantly increased in bacteria recovered from macrophages and mice. This is consistent with previous data showing a transcriptional increase of sodCI upon infection and a corresponding increase in protein levels (13, 44). The levels of β-galactosidase expressed from the sodCII fusion also increased, albeit to a lesser extent, consistent with previous data showing that sodCII is transcriptionally activated in the phagosome (13). However, SodCII protein was barely detected in bacteria recovered from either macrophages or mice. The most plausible explanation is that SodCII is made but degraded in the phagosome, consistent with our model (22).

FIG. 1.

Expression and steady-state levels of SodCI and SodCII in vivo. Strains contain a chromosomal lacZ fusion in which the reporter gene is inserted just downstream of the stop codon for either sodCI-6xhis or sodCII. (A) Bacteria were recovered from LB after 16 h or from macrophages (MΦ) after 16 h of infection. (B) Bacteria were recovered from LB after 16 h or from mouse spleens (M) after 4 days of infection. (C) Same as in panel A, except that the background strain was a ΔhtrA mutant. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from equal numbers of bacteria, separated by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Each set of panels represents a single gel for which the resulting nitrocellulose membrane was cut into sections and processed with primary antibody directed against the indicated protein. These results are representative of experiments performed 2 to 6 times. The strains used were JS905, JS906, and JS907.

Degradation of SodCII could result from either bacterial proteases in the periplasm or phagosomal proteases. HtrA is the primary periplasmic protease that has previously been implicated in Salmonella pathogenesis (29). We tested possible SodCII degradation by HtrA during macrophage infection by repeating the above experiment in an htrA null background. SodCII was expressed in the htrA mutant background in LB, and the steady-state level of SodCII dramatically decreased in macrophages (Fig. 1C). This suggests that HtrA is not responsible for SodCII degradation during macrophage infection. We also know that SodCII, even without metal cofactors, is stable in the periplasm in vitro (21).

The sodCII gene is not regulated in response to zinc.

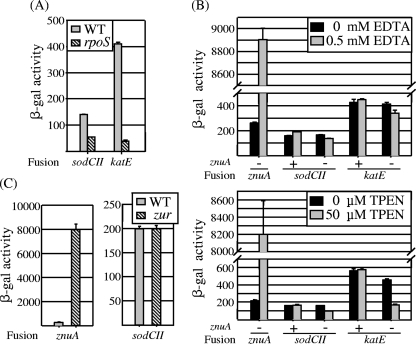

Campoy et al. (4) have shown that Salmonella mutants lacking ZnuA, the periplasmic Zn-binding protein component of the high-affinity Zn transport system, are attenuated, suggesting that the host environment is Zn limited. Ammendola et al. (2) suggested that sodCII transcription is decreased in response to the low-Zn environment, although no specific mechanism was proposed. It is known that sodCII is regulated by the alternative sigma factor RpoS (9, 13, 14); no other regulatory system is known to affect sodCII transcription in Salmonella. To clarify this issue, we asked if sodCII transcription was affected by the Zn concentration of the medium. We assayed β-galactosidase activity produced from the sodCII-lacZ fusion in both wild-type and znuA mutant backgrounds in the presence and absence of chelators. As controls for this experiment, we also monitored expression from single-copy lacZ fusions to znuA, known to be regulated in response to zinc (32), and katE, which is regulated by RpoS (23) (Fig. 2A). Strains were grown in LB, with or without 0.5 mM EDTA (the conditions used by Ammendola et al. [2]) or 50 μM TPEN, a more specific zinc chelator (39). The addition of either chelator caused a dramatic (>35-fold) increase in znuA expression, as expected (Fig. 2B). (Note that the znuA fusion creates a znuA null mutation.) The addition of EDTA or TPEN had little to no effect on expression of either sodCII or katE in a wild-type background. In the znuA mutant background, the presence of chelator did lead to a slight decrease in sodCII expression. Importantly, however, the katE fusion also decreased in expression under these conditions. It should be noted that the znuA mutant grows poorly at these concentrations of chelator. The simplest explanation for these results is that under these restricted growth conditions, the RpoS regulon is not fully induced in the znuA mutant.

FIG. 2.

Transcription of sodCII is regulated by RpoS but is not directly affected by zinc level. (A) β-Galactosidase activity in strains containing sodCII-lacZ or katE-lacZ fusion in wild-type (WT) or rpoS null background, grown overnight in LB. The strains used were JS531, JS908, JS909, and JS910. (B) β-Galactosidase activity in strains containing lacZ fusions to the indicated genes in znuA+ or znuA null background, grown overnight in LB containing either EDTA or the zinc chelator TPEN, as indicated. The strains used were JS911, JS531, JS912, JS909, and JS913. (C) β-Galactosidase activity in strains containing znuA-lacZ or sodCII-lacZ fusion in wild-type or zur null background, grown overnight in LB. The strains used were JS911, JS914, JS531, and JS915.

The genes encoding the Znu transport system are repressed by Zur when the regulator binds Zn (30, 31). Figure 2C shows that in a zur null background, znuA expression was induced 40-fold, analogous to the induction seen in the presence of chelators. Induction of the high-affinity transport system in this mutant likely alters the intracellular concentration of Zn. However, expression of sodCII was unaffected by loss of Zur (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that Zur has no role in sodCII regulation. Together, these data strongly suggest that Zn has no direct role in sodCII expression.

Metal acquisition.

SodC proteins acquire Cu and Zn adventitiously in the periplasm. The metal ions can also be removed from the cofactored proteins by chelation. It has been suggested (2) that differential affinity and stability of metal binding in SodCI and SodCII contribute to their different roles in macrophage survival. We previously examined the steady-state levels of SodCI and SodCII recovered from bacteria grown in the presence of the Cu chelator TETA (21). We performed a similar experiment examining the steady-state activities of SodCI and SodCII recovered from bacteria grown in the presence of the Zn chelator TPEN. We performed a parallel experiment examining the ability of the wild type versus the znuA mutant to grow in various concentrations of the chelator. In the absence of chelator, both SodCI and SodCII, expressed from lac promoters on equivalent plasmids, produced approximately equal absolute levels of SOD activity (Fig. 3A). Subsequent addition of Cu and Zn to the extracts showed that this represented 83% of recoverable SodCI activity and 30% of SodCII activity. At increasing concentrations of TPEN, the amounts of active SodCI and SodCII decreased, with SodCI being more active than SodCII at lower TPEN concentrations (Fig. 3A). At 20 μg/ml TPEN, both SodCI and SodCII activities were reduced to ∼40% of those observed in the absence of chelator. The activities of both enzymes continued to decrease at higher concentrations. A similar trend was observed in our previous TETA experiments (21). Interestingly, 20 μg/ml TPEN was also the concentration at which the znuA mutant started to show a growth defect (Fig. 3B). A znuA mutant was attenuated in an animal model (4; data not shown), suggesting that the phagosome might be limited in Zn. Under these conditions, it is possible that only a fraction of both SodCI and SodCII is active. However, their relative abilities to acquire metals do not seem to explain the different roles of these two enzymes in virulence.

FIG. 3.

SodCI and SodCII activities in the presence of zinc chelator. (A) Strains producing SodCI or SodCII from a plasmid (in an otherwise sod null background) were grown overnight in LB with the indicated concentration of the zinc chelator TPEN. SOD-specific activity was determined from whole-cell extracts. (B) Wild-type and znuA null strains were grown overnight in LB with the indicated concentration of TPEN, and the resulting OD600 was determined. The strains used were JS916, JS917, 14028, and JS918.

Antimicrobial peptides cause release of periplasmic proteins.

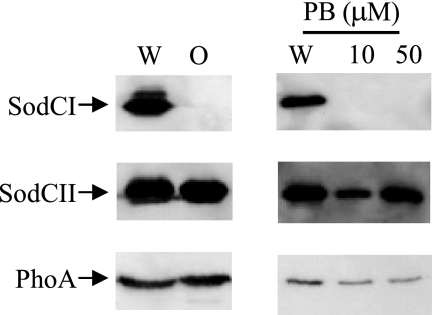

SodCI, unlike other periplasmic proteins, is not released by osmotic shock but rather is “tethered” within the periplasm by a noncovalent mechanism (21, 22). One could argue that osmotic shock is not physiologically relevant. However, it is known that cationic antimicrobial peptides also cause the release of periplasmic proteins (45). We hypothesized that cationic antimicrobial peptides encountered during infection could cause the release of SodCII and other periplasmic proteins and/or expose the periplasmic proteins to phagocytic proteases. SodCI would remain tethered. To test this hypothesis, we compared the release of SodCI, SodCII, and E. coli PhoA, as a control, from Salmonella cells treated with sublethal concentrations of polymyxin B sulfate versus osmotic shock. In each case, proteins from untreated whole cells or in the supernatant from an equivalent number of treated cells were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins of interest were detected by Western analysis. Figure 4 shows that both SodCII and PhoA were quantitatively released by osmotic shock. In contrast, virtually no SodCI was detectable in the supernatant of osmotically shocked cells, consistent with our previous data (21, 22). When cells were treated with polymyxin B sulfate, significant percentages of SodCII and PhoA were released into the supernatant. Again, SodCI was not released under these conditions. Thus, both osmotic shock and treatment with polymyxin B sulfate cause the release of periplasmic proteins, but SodCI remains tethered within the periplasm.

FIG. 4.

Polymyxin causes release of periplasmic proteins. The left panel shows the results of osmotic shock (O) as described in Materials and Methods. The right panel shows the results of treatment at the indicated concentration of polymyxin B (PB). In each case, a whole-cell extract (W) was compared to the supernatant from an equivalent number of cells after treatment. Proteins in each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with primary antibody directed against the indicated protein. The strains used were JS921, JS922, and JS923.

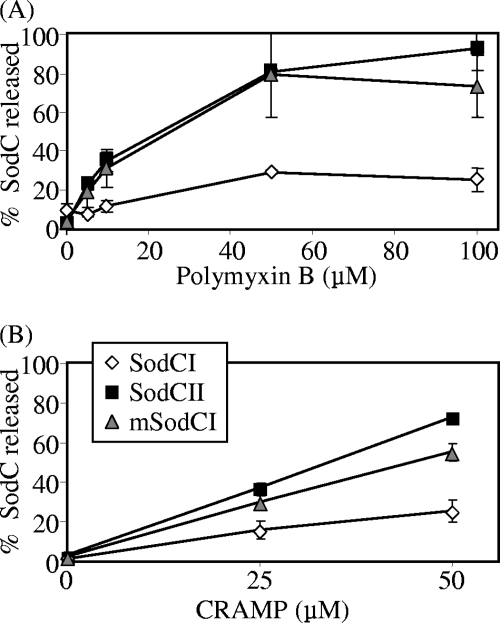

The effect of polymyxin on SodC release from the periplasm was tested at various concentrations. Figure 5A shows that a maximum of 20% of SodCI was released, even in the presence of 100 μM polymyxin. In contrast, almost 100% of SodCII was released under these conditions. We had previously constructed a monomeric SodCI allele by altering two amino acids in the dimer interface (22). This enzymatically active mutant also happened to be released by osmotic shock (22). As expected, this monomeric SodCI was also released by polymyxin treatment, to approximately the same extent as SodCII. It is important that the concentrations tested were sublethal concentrations of polymyxin. At 50 μM, no detectable amount of the cytoplasmic protein glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was released into the supernatant (data not shown), and plating pelleted cells after treatment recovered 85% ± 11% of the starting CFU.

FIG. 5.

SodCII is preferentially released by polymyxin B and CRAMP. Strains producing SodCI, SodCII, or monomeric SodCI (mSodCI) from plasmids (in an otherwise sod-negative background) were treated with various concentrations of polymyxin B (A) or CRAMP (B). The SOD activity released into the supernatant was compared to that in a corresponding whole-cell extract. The strains used were JS924, JS922, and JS925.

Mouse macrophages produce the cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide CRAMP, which is known to contribute to protection against Salmonella infection (38). We evaluated the effect of this antimicrobial peptide by using an in vitro-synthesized 34-amino-acid peptide corresponding to mature CRAMP (12). Upon treatment of Salmonella with increasing concentrations of CRAMP, SodCII was preferentially released compared to SodCI. Monomeric SodCI was also significantly released under these conditions (Fig. 5B). As described above, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was not released under these conditions (data not shown). Together, these data show that treatment with antimicrobial peptides leads to release of periplasmic proteins. SodCI is unusual in that it remains largely tethered within the periplasm.

SodCII can contribute to virulence in a constitutive PmrA background.

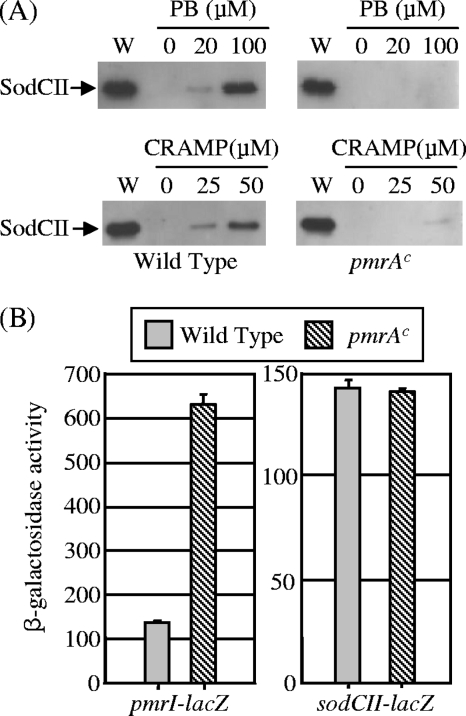

Our model posits that SodCII is degraded by phagocytic proteases that gain access to the enzyme upon disruption of the outer membrane by CAMPs. If this is true, then SodCII should contribute to protection from phagocytic superoxide if it can be protected from proteolysis. The PhoPQ regulon is induced in response to the phagocytic environment. PhoPQ activation leads to induction of the PmrAB two-component system, which in turn induces expression of several genes whose products modify the structure of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), conferring increased resistance to CAMPs (15). Mutations that constitutively activate the PmrA sensor kinase confer resistance to polymyxin and other CAMPs (15, 37, 45). We compared the release of SodCII upon treatment with polymyxin or CRAMP in pmrA(Con) versus wild-type backgrounds. As described above, a large amount of SodCII was released from the wild-type cells by treatment with either 100 μM polymyxin or 50 μM CRAMP. In contrast, little SodCII was released from the pmrA(Con) bacteria under the same conditions (Fig. 6A). The pmrA(Con) mutation had no effect on the regulation of sodCII, whereas the known PmrAB-regulated gene pmrI (42) was clearly induced in this background (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

SodCII is not release by polymyxin B or CRAMP in a constitutive PmrA background. (A) Wild-type (left) and pmrA(Con) (right) strains were treated with the indicated concentration of polymyxin B (PB) or CRAMP. In each case, a whole-cell extract (W) was compared to the supernatant from an equivalent number of cells after treatment. Proteins in each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-SodCII antibody. The strains used were JS926 and JS927. (B) β-Galactosidase activity in strains containing pmrI-lacZ or sodCII-lacZ fusion in wild-type or pmrA(Con) background, grown overnight in LB. PmrA does not control the transcription of sodCII. The strains used were JS928, JS929, JS906, and JS930.

We then tested if SodCII can contribute to virulence in a mouse model of infection when protected from antimicrobial peptides in a pmrA(Con) background. First, we competed a sodCI mutant (which produces wild-type SodCII) against a sodCI sodCII double mutant. In an i.p. competition assay, these two strains competed evenly (Table 2). This finding is identical to previous results (21, 44) and shows that in a wild-type background, SodCII does not contribute to virulence, even in the absence of SodCI. We then performed the same competition assay, except that both strains also contained the pmrA(Con) mutation. In this background, the strain that produced SodCII outcompeted the strain lacking periplasmic superoxide dismutase. This result suggests that when Salmonella is protected from antimicrobial peptides, SodCII can function and contribute to virulence, consistent with our model.

TABLE 2.

Competition assays to measure the contribution of SodCII during infection

| Mouse genotype | Salmonella strain A genotypea | Salmonella strain B genotypea | Median CIb | No. of mice | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | ΔsodCI ΔsodCII | ΔsodCI | 1.14§† | 14 | NS |

| ΔsodCI ΔsodCII pmrA(Con) | ΔsodCI pmrA(Con) | 0.58§ | 18 | 0.01 | |

| Cnlp−/− BALB/c | ΔsodCI | Wild type | 0.10 | 2 | 0.002 |

| ΔsodCI ΔsodCII | ΔsodCI | 0.64† | 11 | 0.01 |

Strains used were JS931, JS932, JS933, JS934, JS935, JS936, and 14028.

Competitive index, calculated as follows: (percent strain A recovered/percent strain B recovered)/(percent strain A inoculated/percent strain B inoculated). The indicated results are significantly different (§, P = 0.05; †, P = 0.05).

Student's t test was used to compare the output and the inoculums. NS, not significant.

SodCII can contribute to virulence in Cnlp−/− knockout mice.

Next, we tested if SodCII can contribute to virulence in a Cnlp−/− mouse, which cannot produce CRAMP (34). First, we competed a sodCI mutant against a wild-type strain in Cnlp−/− mice to ensure that these knockout mice produce phagocytic superoxide (5). The data in Table 2 show that the sodCI mutant was attenuated 10-fold compared to the wild-type strain, similar to the phenotype conferred in normal BALB/c mice (21). Second, the sodCI sodCII double mutant was competed against the sodCI single mutant. The strain lacking SodCII was attenuated compared to the sodCII+ strain. Indeed, the competitive index was strikingly similar to the results observed in the pmrA(Con) background. Thus, either infection of mice that cannot produce CRAMP or protection of the outer membrane by constitutive induction of the PmrAB regulon establishes conditions where SodCII is capable of protecting against phagocytic superoxide.

DISCUSSION

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain 14028 produces two periplasmic superoxide dismutases, SodCI and SodCII. Although some original data suggested that mutations in sodCII attenuated virulence, there is now consensus that only SodCI contributes to protection of Salmonella from phagocytic superoxide (2, 21, 22, 44); SodCII plays no role during infection, even in stains lacking SodCI. Presumably, SodCII does protect against periplasmic superoxide in some environment or condition outside the host (20). Why do virulent strains require the additional phage-encoded enzyme SodCI to survive in macrophages? What prevents SodCII from functioning in the phagosome? The inability of SodCII to contribute to virulence is likely due to multiple factors. SodCI has a slightly higher specific activity (2). The two enzymes might also differ in the ability to function under metal-limiting conditions (2), although they respond similarly when cells are grown in the presence of either Cu or Zn chelators (21) (Fig. 3). Yet these subtle differences in enzymatic activity do not seem sufficient to explain the complete inability of SodCII to contribute to protection against phagocytic superoxide.

The genes encoding SodCI and SodCII are also differentially regulated. However, this differential regulation also does not explain the disparity in function (21). The sodCI gene is controlled by PhoPQ and is induced ∼17-fold in macrophages (13). In this study, we confirmed the sodCI transcriptional induction and a corresponding increase in the amount of protein, consistent with recent reports (2, 44). Expression of sodCII is controlled by RpoS (13). There is no evidence of additional regulation. Our data show that this gene is not controlled in response to Zn levels, as recently suggested (2). We have previously shown that sodCII is induced 3- to 4-fold in macrophages and that induction is RpoS dependent (13). In this study, we confirmed this transcriptional induction in macrophages and mice. However, the steady-state level of SodCII protein did not increase proportionally (Fig. 1). This is consistent with previous reports showing low levels of SodCII protein during infection (2, 44), although it should be noted that the Flag-tagged SodCI and SodCII proteins used by these investigators are enzymatically inactive (10; data not shown). The constructs used in our study are fully active.

Accounting for all the data, our current working model proposes that macrophages deliver a variety of antimicrobial molecules to the Salmonella-containing phagosome, including antimicrobial peptides, proteases, and superoxide. The antimicrobial peptides at least transiently disrupt the outer membrane of the bacterium. Periplasmic proteins such as SodCII are released and/or phagocytic proteases gain access to the periplasm. SodCII is degraded under these conditions. In contrast, SodCI is transcriptionally induced in the phagosome, is tethered within the periplasm, and is inherently protease resistant. These properties allow the protein to detoxify phagocytic superoxide in the face of these additional antimicrobial effectors.

Consistent with this model, we have shown here that if the bacterium is protected from the action of antimicrobial peptides, then SodCII can contribute to pathogenesis. SodCII does not fully replace SodCI under these conditions. This finding suggests that protection from degradation may be incomplete. Indeed, we could not detect a significant increase in the steady-state level of SodCII in the pmrA(Con) background in either macrophages or mice (data not shown), but we know that additional factors are important for protection against antimicrobial peptides. This is evidenced by the fact that a phoP mutant is sensitive to a >100-fold lower concentration of CRAMP than that required to inhibit a pmrA mutant (data not shown). We could not use phoQ constitutive mutants in our experiments because these strains are highly attenuated (28). As outlined above, it is also possible that other factors contribute to the robustness of SodCI action during growth in macrophages.

Our results imply that as Salmonella cells adapt to grow in the macrophage, the periplasmic contents are vulnerable to loss or degradation. Although not all periplasmic proteins would be equally susceptible, it is likely that other periplasmic proteins, in addition to SodCII, are damaged or lost. It depends on the function of the protein whether simple leakage would affect function. For example, we have shown that SodC from Brucella abortus, although released by osmotic shock, is protease resistant and can complement sodCI and protect against phagocytic superoxide (22). But periplasmic binding proteins involved in transport, for example, would be nonfunctional if separated from their membrane components.

Despite this apparent vulnerability, Salmonella cells do adapt and propagate in the macrophage. This is likely a recurring battle, as most macrophages in the host have only a few Salmonella organisms, suggesting that bacteria are constantly being engulfed by new macrophages and must adapt to the new environment (26). Alternatively, once a bacterium adapts, it would be fully prepared for the new macrophage. If our model is correct, we would expect SodCII levels to recover and contribute to protection under these conditions. It is also known that superoxide acts early during macrophage infection, which could further reflect this window of vulnerability during adaptation (46).

Surprisingly little is known about the mechanism by which various antimicrobial effectors of macrophages damage or kill bacteria. Even less is known about the interactions between these killing mechanisms. Evidence suggests that serine proteases are required to proteolytically activate CRAMP (38) and that reactive oxygen-dependent signaling is required to activate transcription of the gene encoding CRAMP (38), as well as other defenses (11, 17). It is also known by in vitro work that antimicrobial peptides can act synergistically and can facilitate the action of lysozyme by overcoming the outer membrane barrier (48), but in vivo data are lacking. Our work provides direct evidence that antimicrobial effectors of macrophages do not act independently; rather, they cooperate to damage bacteria. Namely, antimicrobial peptides allow proteases access to periplasmic proteins, including the bacterial defense against phagocytic superoxide. We have provided evidence that the primary target(s) of superoxide is extracytoplasmic (5), but whether the ability of superoxide to inhibit or kill bacteria is directly enhanced by the action of other effector functions, such as antimicrobial peptides, is an unknown but interesting concept.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI63230 to J.M.S. and AI043521 to J.S.G.

We also thank Brad McGwire for his assistance with the Cnlp−/− mice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammendola, S., M. Ajello, P. Pasquali, J. S. Kroll, P. R. Langford, G. Rotilio, P. Valenti, and A. Battistoni. 2005. Differential contribution of SodC1 and SodC2 to intracellular survival and pathogenicity of Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Microbes Infect. 7:698-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammendola, S., P. Pasquali, F. Pacello, G. Rotilio, M. Castor, S. J. Libby, N. Figueroa-Bossi, L. Bossi, F. C. Fang, and A. Battistoni. 2008. Regulatory and structural differences in the Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutases of Salmonella enterica and their significance for virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 283:13688-13699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader, M. W., S. Sanowar, M. E. Daley, A. R. Schneider, U. Cho, W. Xu, R. E. Klevit, M. H. Le, and S. I. Miller. 2005. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell 122:461-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campoy, S., M. Jara, N. Busquets, A. M. Perez De Rozas, I. Badiola, and J. Barbe. 2002. Role of the high-affinity zinc uptake znuABC system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:4721-4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig, M., and J. M. Slauch. 2009. Phagocytic superoxide specifically damages an extracytoplasmic target to inhibit or kill Salmonella. PLoS One 4:e4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Groote, M. A., U. A. Ochsner, M. U. Shiloh, C. Nathan, J. M. McCord, M. C. Dinauer, S. J. Libby, A. Vazquez-Torres, Y. Xu, and F. C. Fang. 1997. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase protects Salmonella from products of phagocyte NADPH-oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13997-14001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellermeier, C. D., A. Janakiraman, and J. M. Slauch. 2002. Construction of targeted single copy lac fusions using lambda red and FLP-mediated site-specific recombination in bacteria. Gene 290:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang, F. C., M. A. DeGroote, J. W. Foster, A. J. Baumler, U. Ochsner, T. Testerman, S. Bearson, J. C. Giard, Y. Xu, G. Campbell, and T. Laessig. 1999. Virulent Salmonella typhimurium has two periplasmic Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7502-7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueroa-Bossi, N., S. Ammendola, and L. Bossi. 2006. Differences in gene expression levels and in enzymatic qualities account for the uneven contribution of superoxide dismutases SodCI and SodCII to pathogenicity in Salmonella enterica. Microbes Infect. 8:1569-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forman, H. J., and M. Torres. 2002. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling: respiratory burst in macrophage signaling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 166:S4-S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo, R. L., K. J. Kim, M. Bernfield, C. A. Kozak, M. Zanetti, L. Merluzzi, and R. Gennaro. 1997. Identification of CRAMP, a cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide expressed in the embryonic and adult mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13088-13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golubeva, Y. A., and J. M. Slauch. 2006. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium periplasmic superoxide dismutase SodCI is a member of the PhoPQ regulon and is induced in macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 188:7853-7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gort, A. S., D. M. Ferber, and J. A. Imlay. 1999. The regulation and role of the periplasmic copper, zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunn, J. S. 2008. The Salmonella PmrAB regulon: lipopolysaccharide modifications, antimicrobial peptide resistance and more. Trends Microbiol. 16:284-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunn, J. S., and S. I. Miller. 1996. PhoP-PhoQ activates transcription of pmrAB, encoding a two-component regulatory system involved in Salmonella typhimurium antimicrobial peptide resistance. J. Bacteriol. 178:6857-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwinn, M. R., and V. Vallyathan. 2006. Respiratory burst: role in signal transduction in alveolar macrophages. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 9:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho, T. D., N. Figueroa-Bossi, M. Wang, S. Uzzau, L. Bossi, and J. M. Slauch. 2002. Identification of GtgE, a novel virulence factor encoded on the Gifsy-2 bacteriophage of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184:5234-5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imlay, K. R., and J. A. Imlay. 1996. Cloning and analysis of sodC, encoding the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:2564-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korshunov, S., and J. A. Imlay. 2006. Detection and quantification of superoxide formed within the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:6326-6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnakumar, R., M. Craig, J. A. Imlay, and J. M. Slauch. 2004. Differences in enzymatic properties allow SodCI but not SodCII to contribute to virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain 14028. J. Bacteriol. 186:5230-5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnakumar, R., B. Kim, E. A. Mollo, J. A. Imlay, and J. M. Slauch. 2007. Structural properties of periplasmic SodCI that correlate with virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 189:4343-4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loewen, P. C., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1994. The role of the sigma factor sigma S (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:53-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maloy, S. R., V. J. Stewart, and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Genetic analysis of pathogenic bacteria: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY.

- 25.Maringanti, S., and J. A. Imlay. 1999. An intracellular iron chelator pleiotropically suppresses enzymatic and growth defects of superoxide dismutase-deficient Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3792-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastroeni, P., A. Grant, O. Restif, and D. Maskell. 2009. A dynamic view of the spread and intracellular distribution of Salmonella enterica. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCord, J. M., and I. Fridovich. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244:6049-6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, S. I., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. Constitutive expression of the PhoP regulon attenuates Salmonella virulence and survival within macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 172:2485-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mo, E., S. E. Peters, C. Willers, D. J. Maskell, and I. G. Charles. 2006. Single, double and triple mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium degP (htrA), degQ (hhoA) and degS (hhoB) have diverse phenotypes on exposure to elevated temperature and their growth in vivo is attenuated to different extents. Microb. Pathog. 41:174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Outten, C. E., D. A. Tobin, J. E. Penner-Hahn, and T. V. O'Halloran. 2001. Characterization of the metal receptor sites in Escherichia coli Zur, an ultrasensitive zinc(II) metalloregulatory protein. Biochemistry 40:10417-10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patzer, S. I., and K. Hantke. 1998. The ZnuABC high-affinity zinc uptake system and its regulator Zur in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1199-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patzer, S. I., and K. Hantke. 2000. The zinc-responsive regulator Zur and its control of the znu gene cluster encoding the ZnuABC zinc uptake system in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275:24321-24332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pesce, A., A. Battistoni, M. E. Stroppolo, F. Polizio, M. Nardini, J. S. Kroll, P. R. Langford, P. O'Neill, M. Sette, A. Desideri, and M. Bolognesi. 2000. Functional and crystallographic characterization of Salmonella typhimurium Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase coded by the sodCI virulence gene. J. Mol. Biol. 302:465-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinheiro da Silva, F., R. L. Gallo, and V. Nizet. 2009. Differing effects of exogenous or endogenous cathelicidin on macrophage Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunol. Cell Biol. 87:496-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radtke, A. L., and M. X. O'Riordan. 2006. Intracellular innate resistance to bacterial pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1720-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter-Dahlfors, A., A. M. Buchan, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 186:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roland, K. L., L. E. Martin, C. R. Esther, and J. K. Spitznagel. 1993. Spontaneous pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 define a new two-component regulatory system with a possible role in virulence. J. Bacteriol. 175:4154-4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberger, C. M., R. L. Gallo, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. Interplay between antibacterial effectors: a macrophage antimicrobial peptide impairs intracellular Salmonella replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2422-2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shumaker, D. K., L. R. Vann, M. W. Goldberg, T. D. Allen, and K. L. Wilson. 1998. TPEN, a Zn2+/Fe2+ chelator with low affinity for Ca2+, inhibits lamin assembly, destabilizes nuclear architecture and may independently protect nuclei from apoptosis in vitro. Cell Calcium 23:151-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slauch, J. M., M. J. Mahan, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1994. Measurement of transcriptional activity in pathogenic bacteria recovered directly from infected host tissue. Biotechniques 16:641-644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slauch, J. M., and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. cis-acting ompF mutations that result in OmpR-dependent constitutive expression. J. Bacteriol. 173:4039-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamayo, R., A. M. Prouty, and J. S. Gunn. 2005. Identification and functional analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PmrA-regulated genes. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamayo, R., S. S. Ryan, A. J. McCoy, and J. S. Gunn. 2002. Identification and genetic characterization of PmrA-regulated genes and genes involved in polymyxin B resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 70:6770-6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uzzau, S., L. Bossi, and N. Figueroa-Bossi. 2002. Differential accumulation of Salmonella [Cu, Zn] superoxide dismutases SodCI and SodCII in intracellular bacteria: correlation with their relative contribution to pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 46:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaara, M., T. Vaara, M. Jensen, I. Helander, M. Nurminen, E. T. Rietschel, and P. H. Makela. 1981. Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide from the polymyxin-resistant pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. FEBS Lett. 129:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vazquez-Torres, A., J. Jones-Carson, P. Mastroeni, H. Ischiropoulos, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 192:227-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan, H., and R. E. Hancock. 2001. Synergistic interactions between mammalian antimicrobial defense peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1558-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]