Abstract

Streptococcus gallolyticus (formerly known as Streptococcus bovis biotype I) is an increasing cause of endocarditis among streptococci and frequently associated with colon cancer. S. gallolyticus is part of the rumen flora but also a cause of disease in ruminants as well as in birds. Here we report the complete nucleotide sequence of strain UCN34, responsible for endocarditis in a patient also suffering from colon cancer. Analysis of the 2,239 proteins encoded by its 2,350-kb-long genome revealed unique features among streptococci, probably related to its adaptation to the rumen environment and its capacity to cause endocarditis. S. gallolyticus has the capacity to use a broad range of carbohydrates of plant origin, in particular to degrade polysaccharides derived from the plant cell wall. Its genome encodes a large repertoire of transporters and catalytic activities, like tannase, phenolic compounds decarboxylase, and bile salt hydrolase, that should contribute to the detoxification of the gut environment. Furthermore, S. gallolyticus synthesizes all 20 amino acids and more vitamins than any other sequenced Streptococcus species. Many of the genes encoding these specific functions were likely acquired by lateral gene transfer from other bacterial species present in the rumen. The surface properties of strain UCN34 may also contribute to its virulence. A polysaccharide capsule might be implicated in resistance to innate immunity defenses, and glucan mucopolysaccharides, three types of pili, and collagen binding proteins may play a role in adhesion to tissues in the course of endocarditis.

Several studies have reported that the proportion of infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus gallolyticus has increased during the last decades, concomitantly with a decrease of cases due to oral streptococci (35). S. gallolyticus is now becoming the first cause of infectious endocarditis among streptococci in Europe (16). Furthermore, S. gallolyticus endocarditis is associated with rural residency, suggesting transmission from animals (29). However, the reasons for the emergence of this pathogen remain poorly understood. S. gallolyticus belongs to the Streptococcus bovis group known for more than 60 years to cause endocarditis (45). Recently, the former species S. bovis has been divided into four major species (50, 53). S. gallolyticus corresponds to S. bovis biotype I (mannitol fermentation positive), the closely related species S. pasteurianus to biotype II/2 (mannitol negative and β-glucuronidase positive), and the more distantly related species S. infantarius to biotype II/1 (mannitol negative and β-glucuronidase negative). S. macedonicus, the fourth species, commonly found in cheese, is nonpathogenic and also considered a S. gallolyticus subspecies (53, 62). A majority of endocarditis cases was due, among the formerly S. bovis group, to S. gallolyticus strains (4).

Multiple studies have shown that endocarditis due to S. gallolyticus as well as positive blood culture for this species is often associated with gastrointestinal malignancy (4, 6). This association has led to a strong indication for gastrointestinal investigation and endoscopic follow-up in the case of S. gallolyticus infections (66). The association of S. gallolyticus infection with colon cancer is a major but still unsolved issue. It may be just incidental, as the alteration of the digestive mucosa may favor the translocation of the bacteria into the bloodstream. Alternatively, the tumor may contribute to the proliferation of S. gallolyticus in close proximity to the gut epithelium, increasing its probability of translocating through the gut barrier. It has also been suggested that the bacterium itself contributes to carcinogenesis (60, 69). In addition to human disease, S. gallolyticus may also cause diseases in animals, like septicemia in pigeons (19), outbreaks in broiler flocks (11), or bovine mastitis (28).

Independent from its association to disease, S. gallolyticus has been isolated as a tannin-resistant bacterium from the feces of different mammalian herbivores, including the koala (48) or the Japanese large wood mouse (52), and it is also a normal inhabitant of the rumen (39). Its resistance to tannins is linked to its tannase activity, a characteristic which also led this bacterium to be named “gallolyticus” as it is able to decarboxylate gallate, an organic acid derived from tannin degradation. S. gallolyticus is also known to express other degradative functions unique among streptococci, like a bile salt hydrolase or an amylase. These properties allow its multiplication outside the animal host, as S. gallolyticus was isolated from a digester fed with shea cake (derived from the nuts of the African tree Vitellaria paradoxa) rich in tannins and aromatic compounds (12). S. gallolyticus is a commensal of the human intestinal tract but remains a rarely detected (2.5 to 15%) low-abundance species (10, 40). In herbivores, overgrowth of S. bovis may become deleterious. For example, ingestion of large amounts of rapidly fermented cereal grains leads to a destabilization of the rumen flora and to the proliferation of acid-tolerant bacteria, including S. gallolyticus. This is accompanied by the overproduction of mucopolysaccharides that stabilize the foam, resulting in feedlot bloat, a significant cause of economical loss (14).

Virulence and colonization factors of S. gallolyticus in humans are largely unknown. Studies of the bird host have shown that this Streptococcus species expresses a capsular polysaccharide, and five different serotypes have been described (19). In addition, electron microscopy studies have revealed the presence of fimbria-like structures on the surface of S. gallolyticus. It was hypothesized that capsules and/or fimbriae are involved in virulence (63). S. gallolyticus isolates responsible for endocarditis exhibited heterogeneous patterns of adherence to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which suggests that they produce different surface components (55). Recently, a collagen binding adhesin together with 10 putative ECM binding proteins were identified in the draft genome sequence of a human isolate of S. gallolyticus (54).

Here we describe the sequence and analysis of the genome of S. gallolyticus strain UCN34 isolated from a human case of endocarditis associated with colon cancer. Analysis of the predicted proteins revealed unique metabolic and cell surface features among streptococci, which contribute to its adaptation to the rumen and to its ability to cause endocarditis. We showed by comparative genomics that many of the corresponding genes were probably acquired by lateral gene transfer (LGT) from other Firmicutes of the gut microbiota.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus strain UCN34 was isolated in 2001 at the Hospital in Caen (Calvados, France) and is resistant to tetracycline. It was recovered from blood cultures of a 70-year-old man with a 1-month history of intermittent fever. The patient was found to have endocarditis of his native aortic valve. He was successfully treated with amoxicillin and gentamicin. Subsequent digestive endoscopy revealed a colic cancer, which led to a partial colectomy. For the construction of the large insert library and the shotgun libraries, pSYX34 and XL10-blue Kanr (Stratagene) or pcDNA2.1 (Invitrogen) and XL2-blue were used as vectors or recipient strains, respectively. Escherichia coli and S. gallolyticus strains were grown in Luria and brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, respectively.

Sequencing and assembly methods.

Genome sequencing was performed using the conventional whole-genome shotgun strategy (24, 26). Two libraries (1- to 2-kb and 2- to 3-kb inserts) were generated by random mechanical shearing of genomic DNA and cloning into pcDNA-2.1 (Invitrogen). A scaffold was obtained by end sequencing clones from a medium-size insert library (5 to 10 kb) in the low-copy-number vector pSYX34 (68). Recombinant plasmids were used as templates for cycle sequencing reactions consisting of 35 cycles (96°C for 30 s; 50°C for 15 s; 60°C for 4 min) in a thermocycler. Samples were precipitated and loaded onto 96-lane automatic capillary 3700 and 3730 DNA sequencers (Applied Biosystems). In an initial step, 30,240 sequences from the three libraries were assembled into 144 contigs using the Phred/Phrap/Consed software (22, 32). CAAT Box (25) was used to predict links between contigs. PCR amplification products amplified from UCN34 chromosomal DNA as template were used to fill gaps and to resequence low-quality regions using primers designed by Consed. If no link was predicted between contigs, direct sequencing with chromosomal DNA as template was performed. Sequence reactions consisted of 99 cycles (96°C for 30 s; 50°C for 15 s; 60°C for 4 min) in a thermocycler. A total of 250 mM betaine was added to the reaction mixture.

Annotation methods.

The CAAT Box environment (25) was used for genome annotation. Coding sequences (CDS) were defined by combining GeneMark predictions (38) with visual inspection of each open reading frame (ORF) for the presence of a start codon with an upstream ribosome binding site and BlastP similarity searches of the Nrprot database (2). The GeneMark predictions were trained on a set of ORFs longer than 300 codons encoding proteins similar to proteins with known function present in public databases. Initially, only CDS longer than 80 codons were retained. Subsequently, all CDS between 40 and 80 codons were searched using the same matrix, but only those with a high coding probability, as predicted by GeneMark, were retained. In a final step, all intergenic regions were searched for short or truncated genes by BlastX comparisons with protein sequence libraries. Limits of the rRNA operons were identified by homology with the other streptococcal genomes; tRNAs were searched using tRNAscan-SE (41).

All predicted CDS were examined visually. Function predictions were based on BlastP similarity searches and on the analysis of motifs using the PFAM databases. Toppred2 was used to identify transmembrane domains (15), SignalP version 2.0 to predict signal peptide regions (44), and LipPred to predict lipoproteins (58). Orthologs between S. gallolyticus UCN34 and Streptococcus agalactiae (strain NEM316) (31), Streptococcus suis (strain 05ZYH33) (13), Streptococcus thermophilus (strain CNRZ1066) (7), Streptococcus mutans (strain UA159) (1), Streptococcus sanguinis (strain SK36) (67), Streptococcus uberis (strain 0140J) (64), Streptococcus pyogenes (strain M1) (23), Streptococcus pneumoniae (strain TIGR4) (59), and Streptococcus zooepidemicus (strain MGCS10565) (5) were defined as genes showing bidirectional best hits by S. gallolyticus proteome BlastP comparisons. The threshold was set to a minimum of 50% sequence identity and a ratio of 0.8 to 1.25 of the protein length. Multiple sequence alignments were done using T-Coffee, and the phylogenetic trees by a Bayesian analysis using MrBayes at the phylogeny website (http://www.phylogeny.fr/) (20).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The S. gallolyticus UCN34 genome sequence is available from DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL under accession number FN597254.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General properties and comparative genomics.

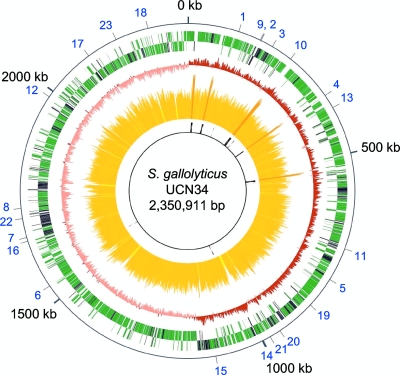

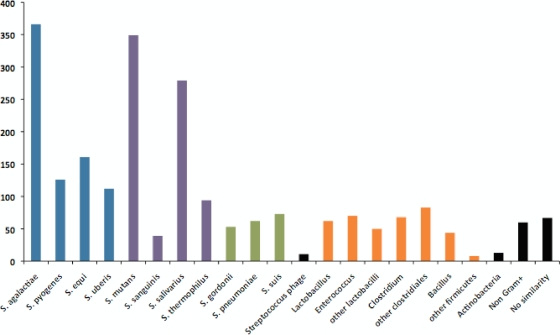

The genome of S. gallolyticus strain UCN34 consists of a single circular chromosome of 2,350,911 bp (Fig. 1). It is second in size among streptococcal strains for which complete genome sequences are publicly available, being only 37 kb smaller than the S. sanguinis SK36 genome (67). The G+C content of the genome is 37.6%. It contains six rRNA operons, 71 tRNA genes, and 2,239 protein coding genes, 13 of which are pseudogenes. The average gene size is 306 codons, accounting for 87% of the genome. These values are similar to the average values reported for the genus Streptococcus (5). We assigned functional annotations to 1,586 proteins, whereas 574 proteins were annotated as conserved hypothetical proteins. S. gallolyticus UCN34 encodes only 79 proteins without similarity to proteins described in the sequence databases (E value threshold of e-3). This small number of orphan genes probably reflects both the large number of sequenced streptococcal genomes and the relative paucity of UCN34 in mobile genetic elements, which commonly carry orphan genes (17). However, 454 genes, i.e., one-fifth of the predicted genes, encode proteins showing a best BlastP hit with proteins from nonstreptococcal species. Most of them are clustered in genomic regions of up to 61 genes (in black in Fig. 1). The best BlastP hits were predominantly with other Firmicutes species, principally with enterococci, lactobacilli, bacilli, and clostridia, bacterial species also present in the rumen microbiota and in the human gut (Fig. 2). This result suggests that these genes were acquired by LGT. Analysis of the functional categories of these genes revealed that they are enriched in functions related to transport, carbohydrate metabolism, cofactor biosynthesis, detoxification, and regulation, which may account for the specific adaptation of S. gallolyticus to the rumen environment (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 1.

Circular genome map of S. gallolyticus UCN34 showing the position and orientation of predicted genes. From outside to inside, circle 1, protein coding genes on the + and − strands, with genes with nonstreptococcal best BlastP hit in black; circle 2, G/C bias (G+C/G−C); circle 3: G+C content, with <30.9% G+C in yellow, between 30.9% and 44.4% G+C in orange, and with >44.4% G+C in red; circle 4, stable RNA coding genes. Numbers in blue on the external circle correspond to genes discussed in the text: polysaccharide utilization (1, gallo_0112; 2, gallo_0162; 3, gallo_0189; 4, gallo_0330; 5, gallo_0757; 6, gallo_1462; 7, gallo_1577-1578; 8, amyE), vitamin biosynthesis (9, panBCD; 10, panE; 11, ribDEAH; 12, bioBDY), polysaccharide biosynthesis (13, gallo_0364-0367; 14, cps operon; 15, gallo_1052-1057), pilus operons (16, gallo_1568-1570; 17, gallo_2040-2038; 18, gallo_2179-2177), and detoxification (19, bsh; 20, gallo_0906; 21, tanA; 22, gallo_1609; 23, gallo_2106). The scale in kb is indicated outside the genome, with the predicted origin of replication being at position 0.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of best BlastP hits. Blue, pyogenic streptococci; purple, viridans group streptococci; green, other streptococci; orange, other Firmicutes; black, others.

To get a better insight into the relationship of S. gallolyticus with other streptococcal species, we compared its genome sequence with those of 10 other completely sequenced streptococcal species (Table 1). S. gallolyticus showed the largest number of orthologous genes with S. agalactiae, a gut-adapted pyogenic Streptococcus species and a major cause of neonatal infections that also causes mastitis in the bovine host, and with S. mutans, a Streptococcus species of the viridans group responsible for dental caries. A high proportion of best BlastP hits was also found with S. salivarius, a commensal Streptococcus species from the dorsum of the tongue and the saliva belonging also to the viridans group (Fig. 2). Therefore, S. gallolyticus shares properties mainly with two oral streptococci from the viridans group and with the gut-associated species S. agalactiae. As these different species do not cluster phylogenetically (57), this gene content conservation likely reflects conserved lifestyle and niche adaptation rather than phylogenetic proximity. In contrast, 687 genes of strain UCN34 did not show any ortholog among the 10 other sequenced streptococci. Among these genes, 244 have, nevertheless, a best BlastP hit with a streptococcal gene. This observation indicates that they have been acquired by LGT from other streptococci or that they are paralogous genes. In addition to having transport, carbohydrate metabolism, and regulatory functions, they are enriched in genes coding for surface proteins and proteins implicated in cell wall biosynthesis (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These functions are probably involved in the interaction of S. gallolyticus with the gut environment and its ability to cause disease in humans (see below).

TABLE 1.

Genome comparison

| Parameter | S. agalactiae NEM316 | S. pyogenes SF370 | S. zooepidemicus MGCS10565 | S. uberis 0140 | S. mutans UA159 | S. sanguinis SK36 | S. gordonii Challis | S. pneumoniae TIGR4 | S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 | S. suis 05ZYH33 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of orthologs | 1,128 | 974 | 1,008 | 1,095 | 1,211 | 1,052 | 1,051 | 972 | 1,048 | 954 |

| No. of CDS | 2,094 | 1,697 | 1,893 | 1,825 | 1,960 | 2,270 | 2,051 | 2,104 | 1,915 | 2,186 |

| % of orthologsa | 54 | 57 | 53 | 60 | 62 | 46 | 51 | 46 | 55 | 44 |

| No. of best orthologs | 372 | 115 | 124 | 134 | 386 | 40 | 59 | 47 | 215 | 56 |

| No. of orthologs identified in a single genome | 40 | 15 | 13 | 18 | 44 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 25 | 24 |

| No. of best BlastP hitsb | 392 | 130 | 163 | 119 | 382 | 45 | 57 | 67 | 258 | 79 |

According to the target genome.

In this species, by BlastP search against the NCBI nr protein database.

S. gallolyticus metabolizes a broad range of carbohydrates of plant origin.

The most remarkable feature of the catabolism of S. gallolyticus as deduced from the genome sequence is that it should have the capacity to degrade diverse complex polysaccharides (Table 2). Strain UCN34 was predicted to utilize plant storage carbohydrates, like various forms of alpha glycoside polymers, including starch and glycogen. Furthermore the genome encodes nine members of the maltogenic alpha amylase family (glycosidase family 13), including a secreted alpha amylase homologous to the Bacillus subtilis amyE gene product. In addition, S. gallolyticus UCN34 should be able to utilize polymers of fructose, levan, and inulin, which are storage polysaccharides in plants, as we identified a gene encoding a secreted membrane-bound fructan hydrolase (fruA). Unique among streptococci is the presence of genes encoding secreted enzymes predicted to be involved in the degradation of insoluble polysaccharides of the plant cell wall. The gene gallo_0162 encodes a putative secreted mannanase with a C-terminal domain similar to known Bacillus mannanases, whereas the N-terminal domain is a carbohydrate-binding domain, and gene gallo_0330 encodes a secreted protein highly similar to Ruminococcus albus endoglucanase V with cellulase activity (47). Strain UCN34 also synthesizes two putative secreted pectate lyases (Gallo_1577 and Gallo_1578). The catalytic domain of these two paralogous proteins is similar to that of the pectate lyase from Clostridium acetobutylicum. Finally, gallo_0189 encodes a putative secreted arabinogalactan endo-1,4-beta-galactosidase similar to a protein from Enterococcus faecium. These genes encoding glycosyl hydrolases are located in chromosomal regions sharing few orthologs with other streptococci, suggesting that they might have been gained by LGT.

TABLE 2.

Secreted polysaccharide hydrolases

| Gene name | Predicted activity | Best blast hit | Binding domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant cell wall constituents | |||

| gallo_0162 | Mannanase | Bacillus | Lectin domain |

| gallo_1578 | Pectate lyase | Clostridium acetobutylicum | |

| gallo_1577 | Pectate lyase | Clostridium acetobutylicum | Lectin domain |

| gallo_0189 | Endo-beta-1,4-galactanase | Enterococcus faecium | |

| gallo_0330 | Beta-1,4-endoglucanase V (cellulase) | Ruminococcus albus | |

| Plant reserve polysaccharides | |||

| gallo_0757 | Alpha-amylase | S. equi | Starch binding |

| gallo_1462 | Pullulanase | S. suis | LPXTG motif |

| amyE | Alpha-amylase | B. subtilis | |

| gallo_0112 | Fructan hydrolase | S. sanguinis | LPXTG motif |

It is known that S. gallolyticus is able to use a broad range of carbohydrates, like cellobiose, fructose, galactose, glucose, lactose, maltose, mannitol, melibiose, raffinose, and trehalose (12). In order to investigate the predictions made from the genome analysis, we further tested the capacity of S. gallolyticus to utilize different carbon sources using the API-50 assay (bioMérieux). This showed that strain UCN34 is indeed able to ferment mannose, N-acetylglucosamine, salicin, sucrose, inulin, starch, glycogen, and gentobiose (data not shown). In agreement with these observations, genome analysis revealed an extremely broad range of sugar permeases, as among the 322 genes possibly involved in transport, 80 were predicted as specific for carbon sources. As an example, strain UCN34 expresses 25 transporters of the phosphotransferase systems (PTS), whereas S. mutans and S. uberis, two species known for their ability to ferment numerous sugars, express only 14 and 15 PTS transporters, respectively (1, 64). These 25 PTS transporters belong to the seven categories defined by Barabote and Saier according to their specificity for different sugars (3): glucose (10), lactose (5), ascorbate (3), fructose (2), mannose (2), galactitol (2), and glucitol (1). Strain UCN34 encodes a great diversity of enzymes to metabolize these carbohydrates, including 33 hydrolases belonging to nine different families. In particular, it encodes 11 phospho-beta-glucosidases (family 1) involved in degrading plant-derived polysaccharides, which is a number similar to that reported for S. uberis, which is known to utilize metabolites deriving from the degradation of plant polysaccharides (64). In addition to the ability to utilize and degrade plant sugars, S. gallolyticus is adapted to use other nutriments of plant origin, as it is the only streptococcus able to utilize malate, a keto acid that occupies a central role in plant metabolism. Strain UCN34 expresses a malolactic enzyme (encoded by gallo_2048) associated with a malate transporter (encoded by gallo_2049).

Taken together, the specific catabolic capacities of S. gallolyticus identified from its genome sequence suggest that they provide a selective advantage to this bacterium for life in the gut environment of herbivores, as it contains a large diversity of compounds of plant origin. S. gallolyticus should be able to degrade them and does not depend on other microorganisms for the initial degradation of insoluble plant polysaccharides which are abundant in this environment.

S. gallolyticus has only few nutritional requirements.

Although most streptococci are auxotrophic for several amino acids and vitamins, previous experiments have shown that most S. bovis strains show an absolute requirement only for biotin, while thiamine stimulates growth, and no requirement for any amino acid (45). In agreement with this observation, we identified from the genome of strain UCN34 the complete biosynthetic pathways for the 20 amino acids (aa) and for selenocysteine. Comparison of the distribution of these genes among streptococci (Table 3) showed that streptococci isolated from the oral cavity, such as S. mutans, S. sanguinis, S. gordonii, and S. pneumoniae, have the capacity to synthesize most amino acids. However, S. gallolyticus and S. mutans are the only two Streptococcus species expressing the glutamate synthase genes (gltAB) clustered in an operon with the glutamine synthetase gene (glnA). The glutamate synthase is a key enzyme in conjunction with glutamine synthetase for the assimilation of ammonium ions into cellular metabolic pathways. The genetic organizations of the amino acid biosynthetic pathways are identical in S. gallolyticus and in S. mutans, which is also a prototroph for all amino acids. The analysis of the distribution of the different amino acid biosynthetic pathways among the 11 Streptococcus species shown in Table 3 suggests that the common ancestor of the genus was proficient in synthesizing all amino acids, and then during evolution, a heterogeneous gene loss took place in the different Streptococcus species, leading to different synthesis capacities. Among nonoral streptococci, S. gallolyticus is particular, as it has kept the ability to synthesize all 20 amino acids.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid biosynthetic pathways in 11 Streptococcus species

| S. gallolyticus UCN34 | S. agalactiae NEM316 | S. pyogenes M1GAS | S. zooepidemicus MGCS10565 | S. uberis 0140 | S. mutans UA159 | S. sanguinis SK36 | S. gordonii Challis | S. pneumoniae TIGR4 | S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 | S. suis 05ZYH33 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| argCJBD | argF | argF | argF | argF | argCJBD | argCJBD | argCJBD | argF | argCJBD | argF |

| argF | argGH | argGH | argF | argF | argF | argF | argGH | |||

| argGH | argGH | argGH | argGH | argGH | ||||||

| aroFBDC | aroFBC | aroFC | aroFC | aroFC | aroFBDC | aroFBDC | aroFBDC | aroFBDC | aroFBDC | aroFBDC |

| aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroEK | aroK |

| pheA | pheA | pheA | pheA | pheA | pheA | |||||

| trpEGDCFBA | trpG | trpG | trpG | trpEGDCFBA | trpEGDCFBA | trpEGDCFBA | trpEGDCFBA | trpEGDCFBA | ||

| tyrA | tyrA | tyrA | tyrA | tyrA | tyrA | tyrA | ||||

| cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK | cysEK |

| dapA | dapA | dapA | dapA | dapA | dapA | dapA | dapA | |||

| dapB | dapB | dapB | dapB | dapB | dapB | dapB | dapB | |||

| dapD | dapD | dapD | dapD | dapD | dapD | dapD | dapD | |||

| lysA | lysA | lysA | lysA | lysA | lysA | lysA | lysA | |||

| glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA | glnA |

| gltAB | gltAB | |||||||||

| glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA | glyA |

| hisCGDBHAFI | hisCGDBHAFI | hisCGDBHAFI | hisCGDBHAFI | |||||||

| ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ilvDBHCA | ||||

| leuABCD | leuABCD | leuABCD | leuABCD | leuA | leuABCD | leuABCD | ||||

| metA | metE | metK | metK | metK | metA | metA | metA | metA | metA | metA |

| metC | metK | metC | metC | metC | metC | metC | metC | |||

| metE | metE | metK | metK | metK | metK | metK | ||||

| metK | metK | |||||||||

| proBA | proBA | proBA | proBA | proBA | proBA | proA | proA | proA | proBA | proA |

| proI | proI | proI | proI | proI | proI | proI | ||||

| serCA | serCA | serCA | serCA | serCA | serB | serCA | serCA | |||

| serB | serB | serB | serB | serB | serB | serB | ||||

| hom | hom thrBC | hom | hom thrBC | hom | hom | hom | hom | hom | hom thrBC | |

| thrBC | thrBC | thrBC | thrBC | thrBC | thrBC | thrBC |

In agreement with the growth requirements, we identified the complete pathways for the synthesis of multiple vitamins, including riboflavin (B2), nicotine amide (NAD, B3), panthotenate (B5), pyridoxine (B6), and folic acid (B9), and partial biosynthetic pathways for biotin (B8) and thiamine (B1) (Table 4). S. gallolyticus is the only Streptococcus species that possesses complete biosynthetic pathways for panthotenate and NAD, whereas riboflavin biosynthesis is present only in S. gallolyticus, S. agalactiae, and S. pneumoniae. Pantothenate biosynthesis involves four enzymatic steps from α-ketoisovalerate and l-aspartate catalyzed by the products of panB, -C, -D, and -E. The panBCD operon of S. gallolyticus is highly similar to those present in various clostridial species, bacteria that are also present in the rumen. In contrast, the panE gene encoding a 2-dehydropantoate 2-reductase is located elsewhere on the chromosome and has an ortholog only in S. thermophilus. The high identity of the two panE genes (97% at the nucleotide level) indicates a recent event of LGT between the two streptococcal species. S. gallolyticus is also able to synthesize NAD from aspartate in three steps. The nadABC operon, encoding a quinolinate synthetase, an L-aspartate oxidase, and a nicotinate-nucleotide pyrophosphorylase, respectively, is organized again similarly to counterparts found in various clostridial species present in the rumen. Finally, phylogenetic analysis of the ribDEAH operon, encoding the enzymes catalyzing the four steps of riboflavin biosynthesis in S. gallolyticus, S. agalactiae, and S. pneumoniae revealed that they do not cluster on the evolutionary tree and that they were thus probably gained independently by LGT (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These genes, like the gene involved in panthotenate and NAD biosynthesis, are clustered in regions predicted to have been acquired by LGT. Although we cannot rule out that all other species have lost these genes, we suggest that unlike with the genes coding amino acid biosynthesis pathways, the above-described functions were acquired from other gut bacteria by LGT and the common ancestor was likely auxotrophic for these vitamins.

TABLE 4.

Vitamin biosynthetic pathways in 11 Streptococcus species

| S. gallolyticus UCN34 | S. agalactiae NEM316 | S. pyogenes M1GAS | S. zooepidemicus MGCS10565 | S. uberis 0140 | S. mutans UA159 | S. sanguinis SK36 | S. gordonii Challis | S. pneumoniae TIGR4 | S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 | S. suis 05ZYH33 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioBDY | bioB | |||||||||

| folCEPBK | folCEPBK | folCEPBK | folCEPBK | folCEPBK | folCEPBK | folCEP | folE | folE | folCEPBK | folCEPBK |

| folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD | folD |

| nadABC | ||||||||||

| nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE | nadE |

| panBCD | panE | |||||||||

| panE | ||||||||||

| ribDEAH | ribDEAH | ribDEAH | ||||||||

| ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF | ribF |

| tenA thiEMD | tenA thiEMD | thiEMD | thiEMD | |||||||

| thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI | thiI |

| thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN | thiN |

The genome analysis suggests that due to the very few nutritional requirements of S. gallolyticus it can grow in an environment containing a diverse range of carbohydrates and poor in amino acids and vitamins, probably enabling it to outcompete auxotrophic bacteria in the rumen and in the human colon.

S. gallolyticus expresses diverse and unique functions among streptococci that are necessary to survive in hostile environments.

S. gallolyticus has a particularly versatile lifestyle, with the capacity to adapt to different environments and to survive harsh conditions. It colonizes different mammalian and bird hosts, causes a broad range of diseases, and was also isolated outside a host as the major species in a continuous digester fed with shea cake (12). In agreement with its adaptation capacities, the genome of strain UCN34 encodes more regulatory proteins than any other streptococcal genome sequenced to date, as 177 genes (7.7% of all predicted genes) are devoted to regulatory functions. This proportion is slightly higher than that of L. monocytogenes (7.3%) (30) and close to that found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.4%) (56), which are both environmental opportunistic pathogens characterized by their capacity to colonize diverse environments.

Another specific characteristic of S. gallolyticus that is important in hostile environments is its ability to degrade tannins, which are toxic polyphenolic compounds that form strong complexes with proteins and other macromolecules. Indeed, a gene, tanA, encoding a 596-aa-long protein 43% identical to the tannase recently described for Staphylococcus lugdunensis (46), is present in its genome. Like S. lugdunensis tannase, TanA is predicted to be exported and contains a conserved lipobox motif (LTACS) at the cleavage site of the signal peptide, indicating that it may be a lipoprotein that remains attached to the cell membrane. Strain UCN34 also expresses a nonsecreted protein similar to TanA (Gallo_1609). This protein has homologs in diverse Firmicutes species and may have a similar hydrolase activity. tanA and gallo_1609 have no counterpart in other streptococcal genomes and were probably gained by LGT.

Degradation of hydrolyzable tannins by S. gallolyticus produces a phenolic compound, gallic acid, which may also be toxic. However, S. gallolyticus is able to decarboxylate gallate and to use it as an alternative carbon supply (12). This capacity may be achieved by two decarboxylases encoded in the genome that have no orthologs in other sequenced streptococcal genomes. Gallo_2106 (PadC) is predicted to be a phenolic acid decarboxylase similar to those present in lactobacilli and bacilli. For example, the B. subtilis PadC protein decarboxylates phenolic compounds and is implicated in the phenolic acid stress response (61). Gallo_0906 belongs to the carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase family. Both activities may account for the ability of S. gallolyticus to decarboxylate gallate but also other phenolic compounds, like protocatechuic p-coumaric or caffeic and ferulic acids, as previously described (12).

Another important feature enabling S. gallolyticus to multiply in the gut environment is its capacity to hydrolyze bile salt conferring resistance to this detergent. This capacity is probably linked to the bsh (gallo_0818) gene encoding a protein highly similar to Listeria monocytogenes bile salt hydrolase (63% identity) (21). This activity, not yet described for another streptococcus, is commonly found in diverse bacteria dominant in the gut community, like Clostridia, Lactobacillus, or Bacteroidetes organisms.

In addition to these enzymatic activities, S. gallolyticus expresses a broad range of transport systems possibly involved in the adaptation to diverse environments. We predicted 25 genes encoding efflux proteins likely involved in detoxification. Strain UCN34 expresses six efflux proteins belonging to the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, whereas other streptococci (S. gordonii and S. uberis) encode not more than three efflux proteins of this family. Furthermore, strain UCN34 encodes 58 proteins probably transporting inorganic compounds. Among those, eight have no counterpart in other sequenced streptococcal genomes (including a sulfate family and two heavy-metal transporters). It also expresses three different iron transport systems; gallo_0590 encodes an NRMAP Mn++, Fe++ transporter; gallo_1771-1774 an iron ABC transporter; and gallo_0619-0620 a ferrous iron transporter. Strain UCN34 is, among the sequenced streptococci, the only one to express all three systems, conferring to S. gallolyticus probably a higher capacity to capture iron, a compound rare in the digestive tract and the environment.

In the gut environment, bacteria need to defend themselves against diverse viruses and other mobile genetic elements (MGE) that may aggress them. CRISPR small RNAs are important in the bacterial response to these invaders. Strikingly, strain UCN34 carries two CRISPR loci located next to each other on the chromosome that belongs to the two major classes of CRISPR loci (8). The first one, with 16 spacer sequences, is associated with three cas (CRISPR-associated) genes, gallo_1439 to gallo_1437. The second locus contains 14 spacers and four cas genes, gallo_1443 to gallo_1446. Together with S. thermophilus, strain UCN34 is the only Streptococcus species whose genome sequence is known that encodes multiple CRISPR systems. They may contribute to its resistance to phages and other mobile elements.

S. gallolyticus synthesizes diverse polysaccharides.

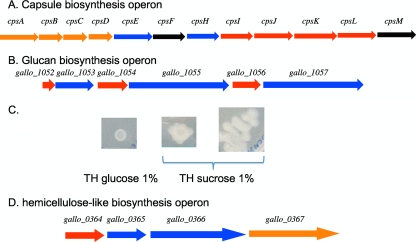

S. gallolyticus is known to produce an extracellular capsule considered a virulence factor. We identified an operon containing 12 genes encoding proteins similar to enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharides of different streptococci, in particular of S. pneumoniae and S. thermophilus exopolysaccharides (Fig. 3A). Its organization and encoded proteins showed a high degree of similarity with those of the S. pneumoniae serotype 23F capsule, although the best BlastP hits for the polymerase (encoded by cpsH) and for the undecaprenyl-phosphate glycosyl-1-phosphate transferase (encoded by cpsE) were to the serotype VIII capsular proteins of S. agalactiae. Thus, this operon probably encodes the functions for the synthesis of a capsular structure of S. gallolyticus, which might confer its resistance to complement and to innate immunity, allowing survival in blood as described for these two pathogenic streptococci (37, 43). It has also been shown that S. gallolyticus expresses the human sialyl Lewis antigen, which may contribute to the ability of this bacterium to cross the vascular endothelium (34). The above-described locus may encode the polysaccharide mimicking the human sialyl Lewis antigen.

FIG. 3.

Loci involved in the synthesis of extracellular polysaccharides. (A) The 12-gene operon responsible for the synthesis of the capsular polysaccharides. cpsA (gallo_0944) encodes a regulator of the LytR family, cpsE (gallo_0948) an undecaprenyl-phosphate glycosyl-1-phosphate transferase, cpsF (gallo_0949) a rhamosyl transferase, cpsH (gallo_0950) a polymerase, cpsI and cpsJ (gallo_0951) sugar transferases, cpsK (gallo_0953) the transporter or flippase, cpsL (gallo_0954) a CDP-glycerol:polyglycerol phosphate glycero-phosphotransferase, and cpsM (gallo_0955) a glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase. The color of the arrow indicates the species encoding the best BlastP hit: red, S. pneumoniae; blue, S. agalactiae; orange, S. thermophilus; and black, other. (B) Putative locus involved in mucopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Genes encoding glycosytransferases are in blue and regulators in red. (C) S. gallolyticus UCN34 grown on TH medium supplemented with 1% glucose or sucrose. (D) Operon putatively involved in the biosynthesis of a hemicellulose-like molecule. gallo_0364 encodes a putative diguanylate cyclase, gallo_0365 and gallo_0366 encode two putative glycosyl transferases, and gallo_0367 encodes a 12-transmembrane domain protein.

It was shown that the production of mucopolysaccharides by S. bovis increases the viscosity of ruminal fluid and stabilizes the foam implicated in frothy feedlot bloat (14). A second locus identified in the UCN34 genome encodes three different glycosyl transferases where each structural gene is associated with a regulatory gene (Fig. 3B). gallo_1053, encoding a nonsecreted transferase, is preceded by an abrB-like regulatory gene, and the two paralogous genes gallo_1055 and gallo_1057, encoding secreted transferases, highly similar to the three glycosyltransferases, GtfA, GtfB, and GtfC, of S. mutans, are each preceded by an rgg-like regulatory gene. In S. mutans, the three extracellular glucosyltransferases are involved in the biosynthesis of insoluble glucans from sucrose. These glucans mediate the adherence of the bacterial cells to the tooth surface and contribute to biofilm formation. The similarity of the genetic organization and the clustering of the three glycosyl transferase genes in S. gallolyticus strongly support the hypothesis that these genes were acquired by LGT from oral streptococci. In order to learn whether strain UCN34 is able to produce glucans, we compared growth on Todd-Hewitt (TH) medium supplemented either with glucose or sucrose (Fig. 3C). Whereas the colonies on TH-glucose medium were small and nonshiny, they were extremely mucoid on medium supplemented with sucrose. This suggests that the glucans produced by these glycosyl transferases represent the mucopolysaccharides produced during feedlot bloat in cattle (14). Thus, among streptococci, S. gallolyticus is the only one known to produce both a capsule and a mucoid extracellular glucan.

Finally, we also identified an operon (gallo_0364-0367) possibly involved in the biosynthesis of hemicellulose (Fig. 3D). These four genes encode two glycosyltransferases, including a putative bacterial cellulose synthase (Gallo_0366), a transmembrane (TM) protein (Gallo_0367), and a putative diguanylate cyclase (Gallo_0364). Gallo_0364 contains the characteristic GGDEF motif and carries, in addition, a PAS domain, indicating that it is probably a sensory protein. Diguanylate cyclases are shown to have important regulatory roles in many bacteria. However, Gallo_0364 is the first example of such a protein described for a streptococcal species. Furthermore, cellulose biosynthesis in Gram-negative bacteria has been shown to depend on cyclic di-GMP (51) and is involved in biofilm formation (27). The polysaccharide produced by this biosynthetic pathway may be part of the external matrix of a S. gallolyticus biofilm.

Srain UCN 34 expresses diverse surface proteins and pili.

Together with the diversity of surface-exposed polysaccharides, a large repertoire of genes encoding surface proteins belonging to different families is present in the S. gallolyticus genome. Many of them may be involved in its colonization capacity and virulence. For example, strain UCN34 encodes a putative fibrinogen/fibronectin binding protein (Fbp) and four proteins related to staphylococcal collagen binding proteins (Gallo_0577, Gallo_1570, Gallo_2032, and Gallo_2179). However, among these four proteins, only Gallo_2179 carries the collagen binding motif and likely binds collagen. Collagen binding has been shown to be required for the capacity of Staphylococcus aureus to cause endocarditis (33). Similarly, these proteins may contribute to the capacity of strain UCN34 to colonize the endocardium.

Nineteen proteins possess both an N-terminal signal peptide and a C-terminal LPXTG sorting motif. Among these proteins, three have predicted enzymatic functions: a subtilisin-like serine protease (Gallo_0748), a pullulanase (Gallo_1462), and a fructan hydrolase (FruA). Furthermore, three operons encoding a sortase C and two LPXTG motif proteins (gallo_1570-1568, gallo_2040-2038, and gallo_2179-2177) were identified. These gene clusters present several characteristics of pilus operons, indicating that strain UCN34 may have the capacity to synthesize three different types of pilus appendages. Unlike Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria polymerize pilus subunits by transpeptidylation reactions catalyzed by sortase C. These pili of Gram-positive bacteria have been shown to contribute to the colonization of specific host tissues, the modulation of host immune responses, and the development of bacterial biofilms (42). In S. gallolyticus UCN34, two of these pilus operons express a protein similar to collagen binding proteins (Gallo_1570 and Gallo_2179), predicted to be adhesins. Similarly, it was recently described for S. gallolyticus strain TX20005 that it encodes three pilus operons and also collagen binding proteins (54). The locus gallo_2179-2177 is identical to the acb locus of strain TX20005, and the locus gallo_2040-2038 is identical to the sbs15 locus. In contrast, the third locus (gallo_1570-1568) is only distantly related to the third locus of strain TX20005 (sbs13). This indicates diversity in the surface protein repertoire among S. gallolyticus isolates.

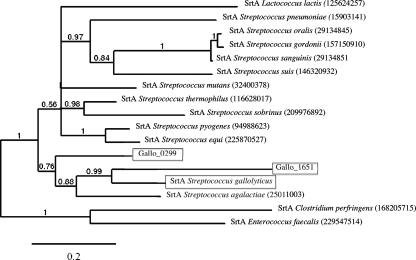

Expression of multiple sortase C proteins associated to pilus loci is common in streptococci. However, strain UCN34 presents the unique property of expressing three highly similar sortase A-encoding genes. In addition to the housekeeping srtA gene located downstream the gyrA gene, we identified two paralogous genes both located on mobile genetic elements. Gallo_1651 is carried by a predicted integrative and conjugative element (ICE) (ICESgal1; encoded by gallo_1646 to gallo_1703) that carries also a Tn916-like conjugative transposon (encoded by gallo_1676-int to gallo_1700) expressing the tet(M) determinant. Furthermore, within Tn916, the previously described plasmid pBC16 which carried the tet(L) determinant is inserted (49). This presence of tet(M) and tet(L) explains the resistance of strain UCN34 to tetracycline. Interestingly, ICESgal1 expresses two LPXTG proteins (Gallo_1649 and Gallo_1675), which may contribute to the conjugative transfer of the element. The third sortase gene, gallo_0299, is also located on an MGE, TnGallo1. TnGallo1 carries also three genes encoding LPXTG proteins and is similar to the recently described conjugative transposon TnGBS2 of S. agalactiae (9). Phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences of these three sortases indicates that they are closely related and clustered within the housekeeping SrtA sequences of streptococci. Therefore, the two additional sortase genes were probably acquired by LGT of srtA genes from related species (Fig. 4). It is tempting to suggest that these additional sortase A genes contribute to the propagation of MGEs by anchoring surface proteins encoded by these elements and involved in their conjugative transfer; however, they may also contribute to the cell wall anchoring of proteins encoded by the genome backbone and to the general fitness of the cell.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationship of sortase A protein sequences with representative sequences from Firmicutes. The three sortase A encoded by strain UCN34 are boxed. Gallo_0299 is expressed by TnGallo1 and Gallo_1651 by ICESgal1. SrtA is the S. gallolyticus housekeeping sortase encoded by the srtA gene located downstream of the gyrA gene. The scale bar represents 0.2 substitutions per site. The numbers at the branches are posterior probabilities indicating the support for the branch. GI numbers for sequences are given in parentheses.

Another important class of surface proteins is lipoproteins. The genome of strain UCN34 encodes 42 lipoproteins (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Twenty-six are ABC transporter substrate binding proteins, one is the above-described tannase, one is a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, and 14 are conserved hypothetical proteins. Further analysis of the deduced protein sequences revealed in 27 out of the 42 lipoproteins the presence of a serine-rich motif following the lipid-modified cysteine residue (Table S1). For example, the cysteine residue in Gallo_1845 is followed by 11 serine residues. Interestingly, alignments with similar proteins from other streptococci revealed that the serine-rich domain is in most cases not conserved. This indicated that this motif might be specific for S. gallolyticus lipoproteins and recently acquired. We thus searched for such motifs in the S. gallolyticus proteins. We identified 16 proteins containing one or several serine-rich domains that were not conserved in orthologous proteins of other streptococci. These serine-rich regions are systematically found in domains predicted to be extracellular (Table S1). Similar polyserine repeat regions have been identified with plant cell wall-degrading enzymes of environmental bacteria, like Cellvibrio japonicus (18), Microbulbifer degradans (36), or Saccharophagus degradans (65). It has been proposed that these flexible spacer regions enhance substrate accessibility for its degradation. Interestingly, in S. gallolyticus, these polyserine repeats are found in surface-exposed proteins with diverse predicted functions not directly related to carbohydrate degradation. Some of them are involved in cell wall biosynthesis (penicillin binding proteins 1A and 2C, d-alanyl-d-alanine-carboxypeptidase, and polyglycerol synthase) or in regulation (protein kinase). They are thus possibly linked to specific interactions of the bacteria with polysaccharides from the environment or that they produce.

Conclusion.

S. gallolyticus is an important cause of endocarditis; still very little is known about the genetic basis of virulence and niche adaptation. Analysis of the S. gallolyticus genome sequence has revealed important features that might help to understand its virulence and survival strategies. We identified an impressive number of functions that are specific to the species S. gallolyticus among streptococci but that are shared with Lactobacillus, Bacillus, and clostridial species belonging to the normal rumen flora, suggesting that S. gallolyticus acquired different functions by LGT from other inhabitants of the rumen to better adapt to this environment. These functions may also provide some explanation for the association of S. gallolyticus and colon cancer. In a healthy human gut, the low prevalence of S. gallolyticus compared to what is observed with ruminants is probably linked to the difference in diet and to the different environments in the rumen and the human gut. However, alterations of the gut due to colon cancer or neoplastic polyps may affect the flux of intestinal content, leading to the accumulation of material, including plant-derived fibers in close proximity to the epithelial cells and to the tumor. This material is metabolically poor but rich in fiber carbohydrates and possibly tannins. Thus, this may now represent a favorable microenvironment for the proliferation of S. gallolyticus. Our genome analysis therefore substantiates the model of overgrowth of S. gallolyticus linked to colon dysplasia and also supports the observation that the prevalence of S. bovis in fecal cultures from patients with carcinoma of the colon was significantly increased compared to that in controls (10, 40). Furthermore, this proliferation together with the alteration of the gut epithelium may favor translocation of the bacteria to the bloodstream. Subsequently, the predicted capsular polysaccharides will protect S. gallolyticus from innate immunity responses, and the surface proteins and pili showing ECM binding properties, including collagen binding, will aid its adherence to endothelium cells as a preliminary step in the development of infective endocarditis.

The genome sequence of strain UCN34 reported here, isolated from human blood, is the first obtained for a S. gallolyticus isolate. It will provide the genomic information for designing a multilocus sequence typing scheme to study the population of S. gallolyticus strains in more detail. This will lead to a better definition of the relationship between strains isolated from humans, bovines, and birds. This will also be the basis for a rational strain selection for further genome sequencing using high-throughput methods to identify putative genomics and functional specificities associated with the different hosts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur Genopole program. V.D. is supported by a grant from the Ministère Délégué à l'Enseignement Supérieur et à la Recherche (France).

We wish also to thank Mathieu Brochet, Carmen Buchrieser, Maria-Jose Lopez, Harold Tjalsma, and Isabelle Rosinski-Chupin for critical comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajdic, D., W. M. McShan, R. E. McLaughlin, G. Savic, J. Chang, M. B. Carson, C. Primeaux, R. Tian, S. Kenton, H. Jia, S. Lin, Y. Qian, S. Li, H. Zhu, F. Najar, H. Lai, J. White, B. A. Roe, and J. J. Ferretti. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:14434-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barabote, R. D., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2005. Comparative genomic analyses of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:608-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck, M., R. Frodl, and G. Funke. 2008. Comprehensive study of strains previously designated Streptococcus bovis consecutively isolated from human blood cultures and emended description of Streptococcus gallolyticus and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2966-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beres, S. B., R. Sesso, S. W. Pinto, N. P. Hoe, S. F. Porcella, F. R. Deleo, and J. M. Musser. 2008. Genome sequence of a Lancefield group C Streptococcus zooepidemicus strain causing epidemic nephritis: new information about an old disease. PLoS One 3:e3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boleij, A., R. M. Schaeps, and H. Tjalsma. 2009. Association between Streptococcus bovis and colon cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolotin, A., B. Quinquis, P. Renault, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, S. Kulakauskas, A. Lapidus, E. Goltsman, M. Mazur, G. D. Pusch, M. Fonstein, R. Overbeek, N. Kyprides, B. Purnelle, D. Prozzi, K. Ngui, D. Masuy, F. Hancy, S. Burteau, M. Boutry, J. Delcour, A. Goffeau, and P. Hols. 2004. Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1554-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolotin, A., B. Quinquis, A. Sorokin, and S. D. Ehrlich. 2005. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology 151:2551-2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brochet, M., V. Da Cunha, E. Couve, C. Rusniok, P. Trieu-Cuot, and P. Glaser. 2009. Atypical association of DDE transposition with conjugation specifies a new family of mobile elements. Mol. Microbiol. 71:948-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns, C. A., R. McCaughey, and C. B. Lauter. 1985. The association of Streptococcus bovis fecal carriage and colon neoplasia: possible relationship with polyps and their premalignant potential. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 80:42-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chadfield, M. S., J. P. Christensen, A. Decostere, H. Christensen, and M. Bisgaard. 2007. Geno- and phenotypic diversity of avian isolates of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis) and associated diagnostic problems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:822-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamkha, M., B. K. Patel, A. Traore, J. L. Garcia, and M. Labat. 2002. Isolation from a shea cake digester of a tannin-degrading Streptococcus gallolyticus strain that decarboxylates protocatechuic and hydroxycinnamic acids, and emendation of the species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, C., J. Tang, W. Dong, C. Wang, Y. Feng, J. Wang, F. Zheng, X. Pan, D. Liu, M. Li, Y. Song, X. Zhu, H. Sun, T. Feng, Z. Guo, A. Ju, J. Ge, Y. Dong, W. Sun, Y. Jiang, J. Yan, H. Yang, X. Wang, G. F. Gao, R. Yang, and J. Yu. 2007. A glimpse of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome from comparative genomics of S. suis 2 Chinese isolates. PLoS One 2:e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng, K. J., T. A. McAllister, J. D. Popp, A. N. Hristov, Z. Mir, and H. T. Shin. 1998. A review of bloat in feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 76:299-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claros, M. G., and G. von Heijne. 1994. TopPred II: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:685-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corredoira, J., M. P. Alonso, A. Coira, E. Casariego, C. Arias, D. Alonso, J. Pita, A. Rodriguez, M. J. Lopez, and J. Varela. 2008. Characteristics of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its differences with Streptococcus viridans endocarditis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daubin, V., and H. Ochman. 2004. Start-up entities in the origin of new genes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14:616-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeBoy, R. T., E. F. Mongodin, D. E. Fouts, L. E. Tailford, H. Khouri, J. B. Emerson, Y. Mohamoud, K. Watkins, B. Henrissat, H. J. Gilbert, and K. E. Nelson. 2008. Insights into plant cell wall degradation from the genome sequence of the soil bacterium Cellvibrio japonicus. J. Bacteriol. 190:5455-5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Herdt, P., F. Haesebrouck, L. A. Devriese, and R. Ducatelle. 1992. Biochemical and antigenic properties of Streptococcus bovis isolated from pigeons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2432-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dereeper, A., V. Guignon, G. Blanc, S. Audic, S. Buffet, F. Chevenet, J. F. Dufayard, S. Guindon, V. Lefort, M. Lescot, J. M. Claverie, and O. Gascuel. 2008. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W465-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dussurget, O., D. Cabanes, P. Dehoux, M. Lecuit, C. Buchrieser, P. Glaser, and P. Cossart. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes bile salt hydrolase is a PrfA-regulated virulence factor involved in the intestinal and hepatic phases of listeriosis. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1095-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frangeul, L., P. Glaser, C. Rusniok, C. Buchrieser, E. Duchaud, P. Dehoux, and F. Kunst. 2004. CAAT-Box, Contigs-Assembly and Annotation Tool-Box for genome sequencing projects. Bioinformatics 20:790-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frangeul, L., K. E. Nelson, C. Buchrieser, A. Danchin, P. Glaser, and F. Kunst. 1999. Cloning and assembly strategies in microbial genome projects. Microbiology 145:2625-2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia, B., C. Latasa, C. Solano, F. Garcia-del Portillo, C. Gamazo, and I. Lasa. 2004. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 54:264-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garvie, E. I., and A. J. Bramley. 1979. Streptococcus bovis—an approach to its classification and its importance as a cause of bovine mastitis. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 46:557-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannitsioti, E., C. Chirouze, A. Bouvet, I. Beguinot, F. Delahaye, J. L. Mainardi, M. Celard, L. Mihaila-Amrouche, V. L. Moing, and B. Hoen. 2007. Characteristics and regional variations of group D streptococcal endocarditis in France. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:770-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser, P., C. Rusniok, C. Buchrieser, F. Chevalier, L. Frangeul, T. Msadek, M. Zouine, E. Couve, L. Lalioui, C. Poyart, P. Trieu-Cuot, and F. Kunst. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1499-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hienz, S. A., T. Schennings, A. Heimdahl, and J. I. Flock. 1996. Collagen binding of Staphylococcus aureus is a virulence factor in experimental endocarditis. J. Infectious Dis. 174:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirota, K., R. Osawa, K. Nemoto, T. Ono, and Y. Miyake. 1996. Highly expressed human sialyl Lewis antigen on cell surface of Streptococcus gallolyticus. Lancet 347:760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoen, B., C. Chirouze, C. H. Cabell, C. Selton-Suty, F. Duchene, L. Olaison, J. M. Miro, G. Habib, E. Abrutyn, S. Eykyn, Y. Bernard, F. Marco, and G. R. Corey. 2005. Emergence of endocarditis due to group D streptococci: findings derived from the merged database of the International Collaboration on Endocarditis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24:12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard, M. B., N. A. Ekborg, L. E. Taylor, S. W. Hutcheson, and R. M. Weiner. 2004. Identification and analysis of polyserine linker domains in prokaryotic proteins with emphasis on the marine bacterium Microbulbifer degradans. Protein Sci. 13:1422-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyams, C., E. Camberlein, J. M. Cohen, K. Bax, and J. S. Brown. 2010. The Streptococcus pneumoniae capsule inhibits complement activity and neutrophil phagocytosis by multiple mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 78:704-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isono, K., J. D. McIninch, and M. Borodovsky. 1994. Characteristic features of the nucleotide sequences of yeast mitochondrial ribosomal protein genes as analyzed by computer program GeneMark. DNA Res. 1:263-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khafipour, E., S. Li, J. C. Plaizier, and D. O. Krause. 2009. Rumen microbiome composition determined using two nutritional models of subacute ruminal acidosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7115-7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein, R. S., R. A. Recco, M. T. Catalano, S. C. Edberg, J. I. Casey, and N. H. Steigbigel. 1977. Association of Streptococcus bovis with carcinoma of the colon. New Engl. J. Med. 297:800-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowe, T. M., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandlik, A., A. Swierczynski, A. Das, and H. Ton-That. 2008. Pili in Gram-positive bacteria: assembly, involvement in colonization and biofilm development. Trends Microbiol. 16:33-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marques, M. B., D. L. Kasper, M. K. Pangburn, and M. R. Wessels. 1992. Prevention of C3 deposition by capsular polysaccharide is a virulence mechanism of type III group B streptococci. Infect. Immun. 60:3986-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nielsen, H., S. Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1999. Machine learning approaches for the prediction of signal peptides and other protein sorting signals. Protein Eng. 12:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niven, C. F., M. R. Washburn, and J. C. White. 1948. Nutrition of Streptococcus bovis. J. Bacteriol. 55:601-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noguchi, N., T. Ohashi, T. Shiratori, K. Narui, T. Hagiwara, M. Ko, K. Watanabe, T. Miyahara, S. Taira, F. Moriyasu, and M. Sasatsu. 2007. Association of tannase-producing Staphylococcus lugdunensis with colon cancer and characterization of a novel tannase gene. J. Gastroenterol. 42:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohara, H., J. Noguchi, S. Karita, T. Kimura, K. Sakka, and K. Ohmiya. 2000. Sequence of egV and properties of EgV, a Ruminococcus albus endoglucanase containing a dockerin domain. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osawa, R. 1990. Formation of a clear zone on tannin-treated brain heart infusion agar by a Streptococcus sp. isolated from feces of koalas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:829-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palva, A., G. Vigren, M. Simonen, H. Rintala, and P. Laamanen. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the tetracycline resistance gene of pBC16 from Bacillus cereus. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Taxonomic dissection of the Streptococcus bovis group by analysis of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) sequences: reclassification of ‘Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli’ as Streptococcus lutetiensis sp. nov. and of Streptococcus bovis biotype 11.2 as Streptococcus pasteurianus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1247-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romling, U. 2002. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 153:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sasaki, E., T. Shimada, R. Osawa, Y. Nishitani, S. Spring, and E. Lang. 2005. Isolation of tannin-degrading bacteria isolated from feces of the Japanese large wood mouse, Apodemus speciosus, feeding on tannin-rich acorns. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 28:358-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlegel, L., F. Grimont, P. A. Grimont, and A. Bouvet. 2004. New group D streptococcal species. Indian J. Med. Res. 119(Suppl.):252-256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sillanpää, J., S. R. Nallapareddy, X. Qin, K. V. Singh, D. M. Muzny, C. L. Kovar, L. V. Nazareth, R. A. Gibbs, M. J. Ferraro, J. M. Steckelberg, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2009. A collagen-binding adhesin, Acb, and 10 other putative MSCRAMM and pilus family proteins of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (S. bovis biotype I). J. Bacteriol. 191:6643-6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sillanpaa, J., S. R. Nallapareddy, K. V. Singh, M. J. Ferraro, and B. E. Murray. 2008. Adherence characteristics of endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus ssp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis biotype I) isolates to host extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tapp, J., M. Thollesson, and B. Herrmann. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships and genotyping of the genus Streptococcus by sequence determination of the RNase P RNA gene, rnpB. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1861-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor, P. D., C. P. Toseland, T. K. Attwood, and D. R. Flower. 2006. LIPPRED: a web server for accurate prediction of lipoprotein signal sequences and cleavage sites. Bioinformation 1:176-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tjalsma, H., M. Scholler-Guinard, E. Lasonder, T. J. Ruers, H. L. Willems, and D. W. Swinkels. 2006. Profiling the humoral immune response in colon cancer patients: diagnostic antigens from Streptococcus bovis. Int. J. Cancer 119:2127-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tran, N. P., J. Gury, V. Dartois, T. K. Nguyen, H. Seraut, L. Barthelmebs, P. Gervais, and J. F. Cavin. 2008. Phenolic acid-mediated regulation of the padC gene, encoding the phenolic acid decarboxylase of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 190:3213-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsakalidou, E., E. Zoidou, B. Pot, L. Wassill, W. Ludwig, L. A. Devriese, G. Kalantzopoulos, K. H. Schleifer, and K. Kersters. 1998. Identification of streptococci from Greek Kasseri cheese and description of Streptococcus macedonicus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:519-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vanrobaeys, M., P. De Herdt, G. Charlier, R. Ducatelle, and F. Haesebrouck. 1999. Ultrastructure of surface components of Streptococcus gallolytics (S. bovis) strains of differing virulence isolated from pigeons. Microbiology 145:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward, P. N., M. T. Holden, J. A. Leigh, N. Lennard, A. Bignell, A. Barron, L. Clark, M. A. Quail, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, S. A. Egan, T. R. Field, D. Maskell, M. Kehoe, C. G. Dowson, N. Chanter, A. M. Whatmore, S. D. Bentley, and J. Parkhill. 2009. Evidence for niche adaptation in the genome of the bovine pathogen Streptococcus uberis. BMC Genomics 10:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weiner, R. M., L. E. Taylor II, B. Henrissat, L. Hauser, M. Land, P. M. Coutinho, C. Rancurel, E. H. Saunders, A. G. Longmire, H. Zhang, E. A. Bayer, H. J. Gilbert, F. Larimer, I. B. Zhulin, N. A. Ekborg, R. Lamed, P. M. Richardson, I. Borovok, and S. Hutcheson. 2008. Complete genome sequence of the complex carbohydrate-degrading marine bacterium, Saccharophagus degradans strain 2-40 T. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wentling, G. K., P. P. Metzger, E. J. Dozois, H. K. Chua, and M. Krishna. 2006. Unusual bacterial infections and colorectal carcinoma—Streptococcus bovis and Clostridium septicum: report of three cases. Dis. Colon Rectum 49:1223-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu, P., J. M. Alves, T. Kitten, A. Brown, Z. Chen, L. S. Ozaki, P. Manque, X. Ge, M. G. Serrano, D. Puiu, S. Hendricks, Y. Wang, M. D. Chaplin, D. Akan, S. Paik, D. L. Peterson, F. L. Macrina, and G. A. Buck. 2007. Genome of the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus sanguinis. J. Bacteriol. 189:3166-3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu, S. Y., and A. Fomenkov. 1994. Construction of pSC101 derivatives with Camr and Tetr for selection or LacZ′ for blue/white screening. Biotechniques 17:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.zur Hausen, H. 2006. Streptococcus bovis: causal or incidental involvement in cancer of the colon? Int. J. Cancer 119:xi-xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.