Abstract

Memory of past cellular responses is an essential adaptation to repeating environmental stimuli. We addressed the question of whether gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-inducible transcription generates memory that sensitizes cells to a second stimulus. We have found that the major histocompatibility complex class II gene DRA is relocated to promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies upon induction with IFN-γ, and this topology is maintained long after transcription shut off. Concurrent interaction of PML protein with mixed-lineage leukemia generates a prolonged permissive chromatin state on the DRA gene characterized by high promoter histone H3 K4 dimethylation that facilitates rapid expression upon restimulation. We propose that the primary signal-induced transcription generates spatial and epigenetic memory that is maintained through several cell generations and endows the cell with increased responsiveness to future activation signals.

Antigen presentation is a central process for the development and function of the adaptive immune system. It is mediated by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules that present peptides to effector cells. MHC class II (MHC-II) proteins are the major antigen-presenting determinants of exogenous peptides to helper T cells to initiate the immune response against pathogens such as bacteria and fungi. MHC-II molecules loaded with the peptide that is being presented are recognized by the T-cell receptor, along with the CD4 coreceptor on the surface of helper T cells (49). This triggers their activation with concomitant cytokine secretion to assist the activation of effector cells such as B cells to initiate antibody production (34).

Loss of MHC-II expression leads to severe immunodeficiency with both cellular and humoral immunity being affected. The syndrome called the bare lymphocyte syndrome (BLS) is characterized by recurrent bacterial and fungal infections and CD4+ lymphopenia (38). BLS patients have been classified into four genetic complementation groups, each characterized by the absence of a particular transcription factor, necessary for MHC-II transcription. These factors, three DNA-binding transcription factors (RFX5, RFXAP, and RFXANK) and the class II transactivator (CIITA), have been isolated by using genetic approaches (14, 30, 46, 47). The DNA-binding factors are recruited synergistically to the conserved elements in the regulatory region of MHC-II genes forming the MHC-II enhanceosome but are not sufficient to drive transcription. The crucial step for transcriptional activation is the recruitment of CIITA.

CIITA is constitutively expressed in professional antigen presenting cells and is induced by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in many other cell types. It is recruited to the MHC-II enhancer via protein-protein interactions with the MHC-II enhanceosome. CIITA is necessary for transcription and is therefore termed the master regulator of MHC-II (37). It orchestrates a number of activatory histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in the promoter region of MHC-II genes through the recruitment of coactivator enzymes like the histone acetyltransferase enzymes p300/CBP and pCAF (16, 21, 44) or the histone methyltransferase CARM1 (58). In addition, it drives transcription through interactions with the general transcription machinery (15, 19). Several PTMs are enriched throughout the gene during the active transcription process (39). It has been shown that altering the histone modification equilibrium with the use of deacetylase inhibitors in the absence of CIITA, results in the induction of MHCII transcription (18).

Apart from epigenetic changes that occur at the promoter during transcription, MHCII gene activity has been shown to correlate with long-range chromatin reorganization. IFN-γ treatment results in locus relocalization to the exterior of the human chromosome 6 territory (50). Such effects may be linked to the binding of activated STAT1 protein (9) or the reorganization of matrix attachment sites across the locus via SATB1-PML complexes (22). The role of PML nuclear bodies (PML-NBs) remains controversial, although they have been described to be rich in transcriptional coactivators (5), and many active genes—including the MHC genes—are found in their vicinity (7, 22, 42). This controversy may be due to the dynamic character of the underlying interactions or the heterogeneous nature of the PML-NBs conferred by the various PML isoforms (5).

Although the local or long range molecular events that mark activation of the MHCII genes have been well studied, very little is known about the postinduction processes. In other systems, long-range chromosomal movements along with histone variants (6, 32), epigenetic modifications (29, 31), chromatin remodelers (17, 23) and catabolic enzymes (54) have been shown to characterize not only transcriptional activation but also transcriptional memory. We show here that restimulation of cells with IFN-γ leads to earlier and stronger MHCII transcriptional induction. This adaptive response is caused by earlier CIITA recruitment facilitated by altered chromatin architecture and increased accessibility on the DRA promoter that are maintained in IFN-γ-primed cells for several cell cycles after removal of the primary stimulus and transcription shut off. These features are attributed to persistent high levels of dimethylation on lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4me2). We also show here for the first time that persistence of this epigenetic mark correlates with a change of the subnuclear localization of the MHC locus that approaches PML-NBs upon activation and remains in their proximity for several cell generations after cease of transcription. Importantly, we show that MLL, the H3K4-methyltransferase complex, and PML-NBs interact via the MLL-WDR5 core subunit and the highly IFNγ-inducible isoform PML-IV, respectively. Importantly, we show that PML has a direct role in the persistence of memory and the H3K4me2 levels in the promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. IFN-γ was used at a concentration of 100 U/ml unless otherwise stated. Cells were left untreated (control) or stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized, and plated on new plates with fresh medium to allow for subsequent cell divisions to occur (primed). During this time period, untreated and IFN-γ-treated cells went through more than four successive replications as calculated by direct cell counting. Cell doubling times (in hours ± the standard deviation) for untreated and IFN-γ-treated cells were 20.3 ± 2.1 and 21.0 ± 1.8, respectively. At 96 h postrelease, IFN-γ was added again to monitor restimulation kinetics in comparison to primarily stimulated cells.

Reagents.

IFN-γ was purchased from R&D Systems (catalog no. 285-IF). Antibodies against the phosphorylated form of STAT1 (Tyr701; catalog no. 9171) from Cell Signaling Technology while total STAT1 (E-23; catalog no. sc-346), RNA pol II (N-20; catalog no. sc-899), and PML (H-238; catalog no. sc-5621) from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies. Antibodies to ac-H3 (catalog no. 06-599), ac-H4 (catalog no. 06-866), H3K4me2 (catalog no. 07-030), and H3K4me3 (catalog no. 07-473) were from Upstate Biotechnology. Antibody to total H3 (ab1791) was from Abcam. Immunostaining was carried out with the anti-MLLN/HRX antibody (catalog no. 05-764) from Upstate and immunoprecipitation with MLL1 antibody from Bethyl Laboratories (A300-086A). BAC clones containing the HLA-DRA and HLA-DRB1 genes (RZPDB737A059D6) and the GLULD1 gene probe (RZPDB737H092085D) were purchased from Imagenes. PML knockdown was carried out with the Accell SMARTpool small interfering RNA (siRNA) reagent from Thermo scientific (E-006547-00-0010).

Plasmids and transfection.

DNA was delivered to cells by using the calcium phosphate DNA precipitation method. Delivery of siRNA was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. PML isoform III and IV expression vectors were constructed on pCDNA3 plasmid (Invitrogen) in frame with the myc epitope cloned N terminally.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated by using the TRIzol reagent according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was carried out using M-murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes) and random hexamers using the manufacturer's protocol. Relative abundance of transcripts was measured by quantitative real-time PCR with SYBR green I. The data were corrected with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression levels for equal loading.

Protein and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Coimmunoprecipitations were done with HeLa cell extracts prepared by lysis buffer (EBC) containing 50 mM Tris 8.0, 170 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Protein extracts were precleared by adding EBC-washed protein G beads for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were removed by centrifugation. The antibody was added to the supernatant, and the reactions were incubated overnight at 4°C. Protein G beads were added after washing with EBC, and reactions were incubated for 3 additional hours. Reactions were next washed extensively with NETN buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF). Laemmli loading buffer was added, and the samples were boiled prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. Input lanes represent 10% of the lysate used for the immunoprecipitation.

A total of 2 × 107 HeLa cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Formaldehyde was subsequently quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min, and the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Cells were lysed in buffer A (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM PMSF) on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were pelleted and resuspended in buffer B (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5% sarcosyl) for 10 min on ice. Chromatin was pelleted and resuspended in buffer C (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M NaCl) and sonicated to 500-bp to 1-kb size fragments, as verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragmented chromatin was centrifuged to remove the insoluble fraction and was precleared with protein G beads. Then, 20-μg portions of chromatin were immunoprecipitated with the respective antibodies in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF) overnight rotating at 4°C. The antibody-chromatin reactions were precipitated with protein G beads for 3 h by rotation. Unbound chromatin was removed by seven washes in RIPA buffer supplemented with 0.1% SDS and NaCl up to 0.5 M. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was reverse cross-linked by 0.5% SDS and 0.2 mg of proteinase K/ml at 55°C for 3 h, followed by overnight incubation at 65°C. DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted and precipitated with ethanol and glycogen. Enrichment of specific sequences in the immunoprecipitated DNA was measured by real-time PCR with SYBR green I and expressed as a percentage of input DNA. PCR was carried out for DRA, as well as GAPDH promoter as a control, which is not affected by IFN-γ treatment.

Restriction enzyme accessibility assay.

A total of 107 HeLa cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and nuclei were isolated with the use of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% NP-40, 0.3 M sucrose). A total of 2 × 106 nuclei were used per digestion reaction, and five reactions were set up for every sample with various concentrations of SspI restriction enzyme (0, 10, 50, 100, or 200 U of enzyme). Digestion was carried out at 37°C in 1× SspI digestion buffer for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2 volumes of nuclear lysis buffer (0.3 M CH3COONa, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, and 0.1 mg of proteinase K/ml) and overnight incubation at 55°C. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in TE buffer. The extent of digestion was measured by quantitative real-time PCR with primers flanking the SspI site (DRA promoter upper and lower) with increased accessibility yielding less PCR product. PCR at the 3′ end of DRA gene with primers (DRA RT, upper and lower) that did not flank any restriction site was carried out in every restriction reaction to correct for equal loading of the samples.

Three-dimensional immunofluorescence in situ hybridization (immuno-FISH) and microscopy.

HeLa cells were cultured on glass coverslips coated with 0.5% gelatin. Cells were treated with CSK buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.3 M sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM PIPES, 0.5% Triton X-100 [pH 6.8]) for 5 min on ice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS for 12 min at room temperature to preserve the three-dimensional structure of the nucleus. Paraformaldehyde was subsequently washed three times with PBS, and the cells were treated with 0.1 N HCl for 10 min at room temperature to remove histones. The cells were subsequently dehydrated with 70, 80, 95, and 100% ethanol. Heat denaturation was carried out in 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 25 mM PO4−3 in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) with nick-translated probe directly labeled with fluorescent nucleotides for 5 min at 80°C, followed by hybridization at 37°C for 16 h. Coverslips were washed three times with 2× SSC (at room temperature and at 37 and 50°C) and blocked with 1% normal goat serum in 1× PBS. Immunostaining was then performed, with α-PML antibody for 1 h, followed by three washes with PBS and then another hour of incubation with secondary antibody labeled with fluorophore. Secondary antibody was washed again three times with PBS, and the samples were mounted on microscope slides. For green fluorescent protein (GFP)/red fluorescent protein (RFP) fusion analysis, cells grown on chambers (Lab-Tek) were transiently transfected and were analyzed alive or after fixation. Confocal microscopy was carried out on a Zeiss Axioscope 2 Plus microscope equipped with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 laser scanning system and Lasersharp 2000 imaging software. Stacks of 0.3 μm were captured and processed. Euclidean distances in three-dimensional space between the genomic loci and the nearest PML body were measured by using Volocity software (Improvision).

Immunostaining.

Cells for immunostaining were fixed essentially as described for three-dimensional immuno-FISH to preserve the three-dimensional structure and directly stained with the respective antibodies. Samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy.

Primers.

The primers used here were as follows. For RT-PCR, we used DRA RT Upper (5′-GAAAGCAGTCATCTTCAGCGTT-3′) and DRA RT Lower (5′-AGAGGCATTGCATGGTGATAAT-3′); CIITA RT Upper (5′-CACAGCCACAGCCCTACTTT-3′) and CIITA RT Lower (5′-CCGACATAGAGTCCCGTGA-3′); PML RT Upper (5′-CCCTGGATAACGTCTTTTTCG-3′) and PML RT Lower (5′-GGAGCTGCTCGCACTCAAAGC-3′); and GAPDH RT Upper (5′-CCTTCCGTGTCCCCACTGCCAAC-3′) and GAPDH RT Lower (5′-CCTTCCGTGTCCCCACTGCCAAC-3′). For ChIP, we used DRA promoter Upper (5′-GTTGTCCTGTTTGTTTAAGAAC-3′) and DRA promoter Lower (5′-TCTTTTCGGAGTCAGTAGAGC-3′); and GAPDH promoter Upper (5′-TGAGCAGACCGGTGTCACTA-3′) and GAPDH promoter Lower (5′-AGGACTTTGGGAACGACTGA-3′).

Statistical analysis.

Frequencies at various PML locus distance intervals were compared by chi-square (χ2) analysis. All distributions had abnormal or uncertain distributions (goodness-of-fit analysis by Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) and Anderson-Darling methods [data not shown]). The data were compared by the Mann-Whitney (MW) test for differences in their median values and by the KS method for differences in their overall frequency distributions.

The corresponding cumulative distributions and their median values were compared by the KS and MW methods to test the null hypothesis that the experimental data belong to the same distribution. To analyze the spatial PML locus proximity patterns, we used the nearest-neighbor approach introduced by Clark and Evans for a three-dimensional space (10). Spherically modeled nuclear volumes of untreated, IFN-treated, or primed cells were calculated from their threshold pixel areas at equatorial confocal planes. Values of nuclear volume and PML abundance were fed into the statistical parameters specified by the above approach to generate estimates of particle (PML + loci) densities in the nuclear volume, their theoretically expected mean minimal distances (Re), their associated standard deviations, and their probability distributions under the different experimental conditions. The ratio R of experimentally calculated mean minimal distance (Ro) over Re is a measure of departure from randomness. Pairs of experimental and their matched theoretical were compared to calculate their associated standard variant Z and its associated probability under the normal curve. Simulated and experimental distributions were further compared by using the KS test.

RESULTS

Memory of previous transcription leads to enhanced MHC-II induction by IFNγ.

To examine the transcriptional status following stimulus withdrawal, we studied the IFN-γ-inducible HLA-DRA gene, a well-studied MHCII model gene, in epithelial cells. After induction with IFN-γ, cells were subsequently released and left to grow in parallel with untreated cells for ∼96 h (primed) to allow return of the mRNA back to its uninduced levels (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Primed cells were then restimulated with IFN-γ, and the kinetics of induction were monitored in comparison to the primarily stimulated cells (Fig. 1A). The RNA levels of HLA-DRA and its activator CIITA were examined in control and primed cells by qRT-PCR after stimulation with the cytokine. Production of DRA mRNA in primed cells appeared earlier (4 h or less versus 6 h in control cells) and reached 2.5-fold higher levels relative to similarly treated unprimed cells (Fig. 1B). This was also found for other IFN-γ-inducible MHCII genes examined but not the constitutively expressed MHC class I HLA-A gene (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting the involvement of an MHC-II locus-wide mechanism.

FIG. 1.

“Memory” of previous transcription allows enhanced DRA induction by IFN-γ. (A) HeLa cells were left untreated (control) or were treated with IFN-γ for 24 h. IFN-γ was removed by three washes with PBS. Cells were trypsinized and replated and were left to proliferate for 96 h (primed) before restimulation (primed + IFN-γ). Treatment occurred in parallel in primarily induced cells for comparison (control + IFN-γ). (B and C) qRT-PCR for DRA (B) and CIITA mRNA (C) in the samples described above. (D) Kinetics of STAT1 phosphorylation. Western blot analysis of phospho-STAT1 (first row) total STAT1 (second row) and loading control RNA Pol II (third row) in control and primed cells. (E and F) qRT-PCR analysis of HLA-DRA (E) and CIITA (F) mRNA after treatment with 0, 1, 10, and 100 U of IFN-γ/ml for 12 h. Shown are the mean values and standard deviation bars from more than three experiments.

To exclude the possibility that this effect was due to faster accumulation of the master regulator CIITA, we measured in parallel the CIITA mRNA levels by qRT-PCR and found no significant difference in induction kinetics between primed and control cells. We next examined IFN-γ signaling by STAT1 phosphorylation, the major transducer of IFN-γ and found identical kinetics of tyrosine 701 phosphorylation between control and primed cells (Fig. 1D). Thus, changes in the IFN-γ/CIITA signaling pathway activity did not account for the observed enhanced transcriptional response.

To examine whether priming could stimulate responses to limiting doses of IFN-γ, we stimulated control and primed cells for 12 h with various concentrations of the cytokine ranging from 1 to 100 U/ml. We observed that HLA-DRA responded to even 1 U of IFN-γ/ml in primed as opposed to control cells, whereas CIITA transcription was almost identical in both situations (Fig. 1E and F). Collectively, these data indicate that primary IFN-γ-mediated expression generates a memory state that lasts for several cell divisions. This process enables the MHC-II promoter to respond more efficiently even to low IFN-γ levels.

Past transcriptional activity generates a prolonged permissive chromatin state that facilitates expression upon restimulation.

Since IFN-γ signaling and CIITA transcription were identical in control and primed cells, we sought to determine whether the local chromatin state of the DRA promoter was involved in the molecular mechanism responsible for the facilitated transcription of primed cells. Earlier results have shown that after IFN-γ, CIITA recruitment coincides with increasing promoter occupancy by chromatin remodelers, coactivators, Pol II kinases, and activatory histone modifications (39, 43, 57).

Therefore, we compared the chromatin of primed versus unprimed control cells after IFN-γ stimulation under matched parallel conditions regarding the promoter occupancy by two activatory posttranslational modifications (PTMs), namely, the histone H3 acetylation (H3ac) and lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and the coactivator CIITA (Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively). ChIP results showed minimal H3ac but accelerated and enhanced H3K4me3 and CIITA occupancy, detectable at even 2 h after IFN-γ. In all cases, excess occupancy slowly decreased over 24 h of IFN-γ treatment.

FIG. 2.

Persistent alterations of the DRA promoter chromatin organization by IFN-γ. ChIP from primed or control HeLa cells that were treated with IFN-γ for the indicated time points using antibodies against H3ac (A), HeK4me3 (B), and CIITA (C). (D) Outline of the restriction enzyme accessibility method showing the SspI target and flanking primer sites on the DRA promoter. (E and F) Restriction enzyme accessibility using increasing amounts of SspI enzyme (E) and DRA promoter ChIP assay using antibody against histone H3 in HeLa cells (F). Control, untreated; 24-h IFN-γ, processed at the end of a 24-h IFN-γ treatment; primed, cells treated with IFN-γ for 24 h, released, and left to grow for 96 h before processing. In all cases, the mean values and standard deviation bars were calculated from more than three experiments.

To investigate the mechanism of enhanced CIITA recruitment, we studied the promoter chromatin architecture by the restriction enzyme accessibility assay. It has been previously shown that an SspI restriction site at −80 bp from the transcription start site of the DRA gene (outlined in Fig. 2D) becomes accessible to digestion upon transcriptional activation (28). Digestion with increasing amounts of SspI and detection of the undigested DNA with qPCR revealed that the DRA promoter of IFN-γ-treated but not untreated cells was sensitive to the enzyme. Increased accessibility of the locus persisted throughout subsequent generations long after transcriptional shutoff in primed cells (Fig. 2E).

Nucleosome depletion has been observed close to transcription start sites of active or transcriptionally poised genes by ChIP of histone H3 (25, 33, 35). Monitoring histone H3 abundance by ChIP showed that DRA gene activation results in reduced total histone H3 levels that remain low in the promoter of primed cells 4 days after release from the primary stimulus (Fig. 2D). For comparison, we also checked the H3 occupancy of the IFN-γ-inducible CIITA promoter IV. We also found that there was no depletion of H3 in any of the experimental conditions used (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material).

We conclude that IFN-γ-mediated transcriptional activation results in a promoter-specific chromatin reorganization manifested by high accessibility and nucleosomal depletion that persists long after removal of the stimulus and transcriptional shutoff. This open chromatin environment in primed cells may facilitate CIITA recruitment at lower protein abundance during restimulation and earlier transcription onset.

Persistence of H3 lysine 4 dimethylation for several cell generations as a stable epigenetic mark.

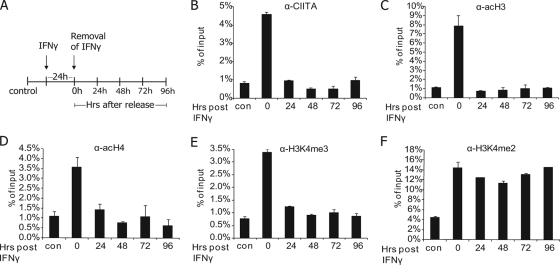

To examine potential epigenetic determinants of promoter sensitization, we monitored the time course of acetylation and histone H3 lysine 4 (K4) methylation of the HLA-DRA promoter after release from IFN-γ (approximately every cell population doubling) as outlined in Fig. 3A. CIITA recruitment was diminished rapidly after removal of the stimulus as found by ChIP, in accordance with the very short half-life of the protein, which is ∼30 min (40) (Fig. 3B). Acetylation of histones H3 and H4 correlated well with CIITA recruitment and returned to basal levels quickly after release (Fig. 3C and D) (4). We next studied histone lysine methylation that has been reported to correlate with the DNase I sensitivity of chromatin (41). Trimethylation of histone H3 K4 (Fig. 3E) was also found to correlate with CIITA recruitment and active transcription, as has been shown in other experimental systems (31). In contrast, increased H3K4 dimethylation was maintained for at least four cell generations after removal of IFN-γ at the DRA promoter (Fig. 3F) but not at the CIITA promoter IV (see Fig. S3B in the supplemental material).

FIG. 3.

Stability of epigenetic modifications after transcription shut off. (A) HeLa cells were treated with IFN-γ for 24 h and then washed free of cytokine and further cultured. Chromatin was isolated from the cells every 24 h to study histone modifications on the HLA-DRA promoter. (B, C, D, E, and F) qPCR on chromatin samples immunoprecipitated with antibodies against CIITA (B), acetylated H3 (C) and H4 (D), trimethylation (E), and dimethylation (F) of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3 and H3K4me2, respectively). con, untreated control cells. Shown are the time points (in hours) after release from the cytokine. The mean precipitate as a percentage of input chromatin and the standard deviations are shown.

Thus, the initial transcriptional activity causes both short- and long-lasting epigenetic alterations of the DRA promoter chromatin architecture. In particular, the memory state correlates with maintenance of high H3K4me2, increased enzyme accessibility of the chromatin, and fast transcriptional induction.

Relocalization of the MHCII locus closer to PML bodies upon gene activation is maintained in primed cells.

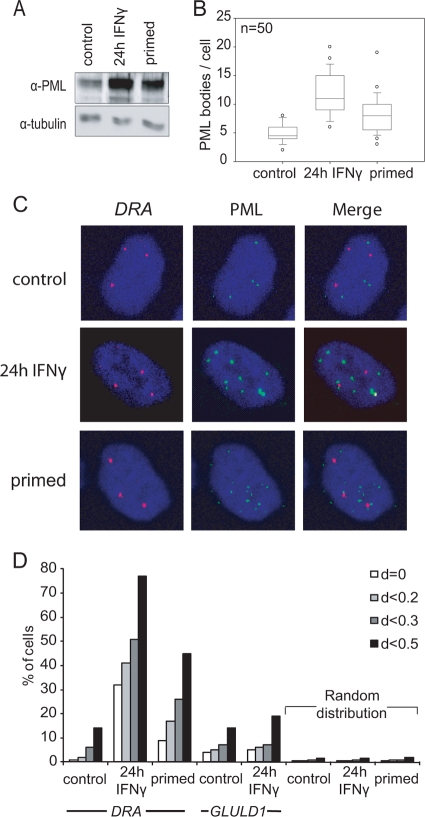

Earlier studies have shown that MHCII gene induction by IFN-γ is accompanied by long-range processes manifested by changes of the territorial locus topology (50). Altered loop formation due to differential anchoring of SATB1-PML protein interactions that affect the expression of individual MHC-I genes (22). PML-NBs have been previously found to associate with transcriptionally active parts of the genome (51). Interestingly, PML expression is also induced by IFN-γ (24, 45). Based on these findings, we tested whether the PML protein could participate in the transcriptional memory process. The PML protein abundance after IFN-γ treatment was found to increase and remain high even 96 h later (Fig. 4A), that is, long after MHC-II or CIITA transcription ceases. The number of PML bodies per nucleus in three-dimensionally preserved nuclei was measured by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy and was also found to significantly increase in IFN-γ and primed cells in accordance with the protein levels (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Increased MHCII locus-PML-NB association by IFN-γ treatment persists long after transcription shutoff. (A) Western blot for PML protein detection in untreated (control), IFN-γ-treated, and primed HeLa cells. (B) Immunofluorescence with an anti-PML antibody and confocal microscopy capturing all Z-stacks on three-dimensionally preserved nuclei. The numbers of nuclear bodies per cell (n = 50 cells per group) were calculated and plotted in a box (median, lower and upper quartile)-and-whisker (upper and lower percentiles) graph. P < 0.0001 was found in all pairwise comparisons using the MW test. (C) Three-dimensional immuno-DNA FISH and confocal microscopy were essentially performed as in panel B for simultaneous detection of PML-NBs and the HLA-DRA locus. Representative cells are shown with the HLA-DRA locus (red) and PML (green) in the DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-stained nucleus (blue). (D) Minimum Euclidian distances between each of the loci of every cell and PML-NBs were measured for HLA-DRA and GLULD1 genes. One hundred cells were scored in each group. The percentage of cells are shown containing at least one allele within the indicated distance (d = distance in μm). Simulated random distributions for the DRA and GLULD1 experimental groups are also shown. A detailed statistical analysis using KS and MW tests is presented in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

To examine the relationship of PML bodies to the MHCII locus, immunostaining was performed simultaneously with fluorescence in situ hybridization (immuno-FISH) to DNA of the HLA-DRA locus in HeLa cells. HeLa cells are polyploid and contain three copies of chromosome 6, as has been shown by karyotyping (8, 26). Visual inspection showed a closer locus-PML association in IFN-γ or primed relative to untreated cells (Fig. 4C). To quantitate this, the minimum distance of the MHCII locus to the closest PML body per nucleus was measured in untreated, IFN-γ-treated and primed cells (Fig. 4D). Only 1% of the untreated cells had at least one DRA locus in contact with a PML body (MHC-II-PML minimum distance of d = 0), while this percentage increased to 35% in the IFN-γ-treated cells (Fig. 4D, white bars, χ2 [P < 0.0001 against control]). In the primed state, 9% of the cells had at least one locus touching a PML body (control versus primed, P = 0.018). About 80% of the IFN-γ-treated cells and 45% of the primed cells but only 7% of the control cells had alleles in the vicinity of a PML body, at a distance of <0.5 μm (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4D, black bars). The closer spacing of the MHCII loci in IFN-γ-treated and primed cells over the untreated ones were maintained across a wide range of distances (pairwise χ2 tests showed the highest P of 0.007 up to 1.5 μm, with the exception of distance d < 0.1 μm, where P = 0.023).

To evaluate the specificity of these spatial changes, we also scored the distribution of GLULD1, an irrelevant locus located ∼30 Mb away from the MHC-II cluster on the same chromosome (Fig. 4D). Only 4% of the control and 5% of the IFN-γ-treated cells had at least one GLULD1 allele in contact with a PML-NB (P > 0.9). Similarly, no significant frequency changes were recorded at the 0- to 0.5-μm range. A total of 14% of the control cells and 19% of IFN-γ-treated cells (P = 0.39) had at least one GLULD1 allele within this range to the nearest PML-NB (Fig. 4D), and that pattern was practically the same with the HLA-DRA distribution in control cells. The same pattern was maintained at longer range (lowest P > 0.2 for up to 2- to 3-μm distances). To link PML locus proximity to transcriptional memory manifestation, a similar immuno-DNA FISH analysis was carried out for CIITA located on chromosome 16. Locus PML distance distributions were marginally reduced upon induction and returned to the original pattern in primed cells (see Fig. S3D in the supplemental material).

To examine whether PML-locus distances are randomly distributed in the nuclear space, we used a nearest-neighbor approach (10) to generate distance distributions modeling the different experimental conditions. The estimated parameters for the different simulations and statistical analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) demonstrate that the experimental data depart significantly from random distributions and are compatible with a nonrandom spacing pattern that is in line with a clustered positioning. This is probably due to physical constraints within the nuclear volume, for example, the territorial organization of chromosomes, which limits the available space.

IFN-γ generates a strong locus-specific distribution shift to smaller MHCII-PML distances that is maintained long after gene inactivation. In contrast, both the GLULD1 and CIITA loci show a minimal and similar decrease in distance distribution upon IFN-γ treatment that may reflect a global architectural change of the nuclear environment.

Increased PML-MLL interaction correlates with PML-facilitated DRA transcription.

To examine the role of PML in the persistence of elevated H3K4me2 on the DRA promoter, we did double immunostaining with α-PML and α-MLL antibodies in paraformaldehyde-fixed nuclei to preserve the three-dimensional structure of the nucleus (Fig. 5A). MLL is a multisubunit complex with K4 methyltransferase activity that is regulated by its WDR5 and ASH2L subunits (11), which is important for the maintenance of expression of Hox genes (27). MLL has a speckled nuclear pattern (53). We observed increased colocalization of PML bodies with the MLL speckles in IFN-γ-treated or primed cells. Quantitation (recording touching or overlapping signals) shows that 28% of the control, but 0 and 6% only of the IFN-γ-treated or primed cells, respectively, had no PML-MLL association (whereas 50% of cells had one, three, or five PML-MLL bodies in contact in control, primed, or IFN-γ-stimulated groups, respectively). Consequently, IFN-γ treatment or priming significantly shifted the distribution of PML-MLL contacts per cell to much higher levels (P < 0.0001 [KS] in all pairwise comparisons; Fig. 5B). To further study the PML-MLL association, we carried out coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins. The results in Fig. 5C (top) shows that MLL coprecipitated less-abundant PML isoforms, most likely type III or IV, judging by their mobility. Overexpression of the above myc-tagged PML isoforms separately in HeLa cells, followed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that PML-IV, but not PML-III, specifically interacts with MLL (Fig. 5C, bottom). To further investigate the PML-MLL interaction, we coexpressed the GFP fusions of the WDR5 and ASH2L MLL subunits along with mRFP-PML-III or -PML-IV and examined them by confocal microscopy. The results in Fig. 5D show that the WDR5 but not ASH2L regulatory factor is recruited by PML-IV to a much greater extent than PML-III-containing PML bodies. As a control, the enhanceosome factor RFX5 was found not be recruited by either PML isoform. The results from coimmunoprecipitation confirmed the imaging experiments (results not shown). Overall, these data provide a physical basis for the increased recruitment of MLL to PML bodies after IFN-γ treatment.

FIG. 5.

PML interacts with the MLL complex and coactivates DRA transcription. (A) Subnuclear localization of endogenous PML and MLL imaged after double immunostaining with anti-PML (green) and anti-MLL (red) antibodies: untreated control, IFN-γ-treated, and primed HeLa cells are shown. (B) Cumulative distribution of the MLL-PML association events per cell in each of the three conditions of the experiment described in panel A. The data are based on n = 50 cells/group and were subjected to KS analysis as described in the text. (C) Protein immunoprecipitation from HeLa whole-cell extracts with antibody specific to MLL in control and IFN-γ-treated cells and Western blot with antibody to all PML isoforms (upper panel, left and right, respectively). The immunoprecipitated band is marked with an arrow. Lysates of cells expressing myc-tagged PML isoforms III (middle) and IV (bottom) were immunoprecipitated with anti-MLL antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-myc. The lower right panel shows specificity of immunoprecipitation using an isotype control antibody. (D) Preferential recruitment of WDR5 by PML-IV. Cells cotransfected with mDsRed-PML-III (left panel) or -IV (right panel) and each of GFP- ASH2L, -WDR5, and -RFX5 were examined by dual-channel confocal microscopy as indicated. (E) PML knockdown reduced MHC-II but not CIITA expression. HeLa cells were treated with 80 nM scrambled siRNA (□) or with siRNA specific to all PML isoforms (▪) for 3 days prior to IFN-γ treatment for the indicated time points. qRT-PCR was used to measure the kinetics of transcriptional activation of DRA (left) in relation to its activator CIITA (middle) and the efficiency of PML knockdown (right). (F) PML enhances the CIITA-mediated induction of the DRA gene. HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 100 ng of a CIITA-expressing plasmid, along with increasing amounts of PML-expressing plasmids as indicated. qRT-PCR was used to measure the transcription fold change relative to CIITA alone (set at 1). The results show means and standard deviations from three experiments.

To show the functional role of PML for DRA transcriptional activation, we performed knockdown experiments of PML by siRNA prior to the treatment of cells with IFN-γ. The efficacy of the knockdown was examined by qRT-PCR analyses to detect all of the PML transcripts (Fig. 5E, right graph) and by immunostaining experiments (data not shown) showing blocking of the IFN-γ-mediated increase of PML protein. PML knockdown resulted in reduced inducibility of DRA to about half of the control at 12 h after IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 5E, left graph) without affecting CIITA expression (Fig. 5E, middle graph).

To correlate the above with the PML isoform specific interaction with MLL, we examined the effect of cotransfected CIITA- and PML-expressing plasmids. Figure 5F shows a PML dose-dependent increase in the CIITA-mediated transactivation of DRA. In line with the above results, PML-III had a small effect, whereas PML-IV significantly enhanced DRA transcription and show a PML isoform-specific coactivatory potential.

Overall, these results point to a positive role of the PML body in IFN-γ-mediated activation of the MHCII locus. IFN-γ increases the amount and isoform composition of PML bodies and facilitates recruitment of MLL components. In this line, earlier data have stressed the role of PML in transcription via its association with coactivators and other regulatory factors (13). This, in turn, may have an important role in maintaining a microenvironment that promotes expression of gene neighbors, as shown by both overexpression and knockdown experiments of PML.

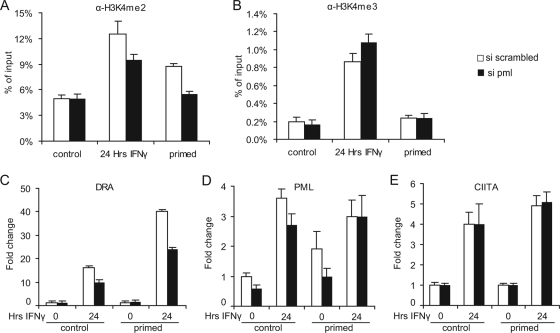

Loss of memory in PML-depleted cells.

Since we established the involvement of PML in DRA transcription during induction with IFN-γ, we next examined its role in the persistence of elevated levels of dimethylation on histone H3K4. HeLa cells were treated as in Fig. 1A and were subjected to PML knockdown by siRNA prior to primary stimulation and anti-H3K4me2 ChIP was carried out on DRA promoter (efficiency of PML knockdown was verified by qRT-PCR [data not shown]). Depletion of PML during priming resulted in lower induction and failure to maintain H3K4me2 levels in primed cells, as opposed to cells treated with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 6A). Significantly, trimethylation of H3K4 was not affected by siPML (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

PML depletion compromises the maintenance of H3K4me2 and the magnitude of the memory response. HeLa cells were exposed to siRNA against PML or scrambled 24 h prior to the addition of IFN-γ, washed free of the reagents, and left to grow for 4 days (primed). (A and B) ChIP assays on DRA promoter using antibodies to H3K4me2 (A) and H3K4me3 (B) from control cells, cells treated with IFN-γ, or primed cells. (C, D, and E) The mRNA abundance of DRA (C), PML (D), and CIITA (E) was measured in control and primed cells that were left untreated or were stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h.

Since PML knockdown during priming affected the maintenance of the H3K4me2 mark on the promoter, we studied whether these cells could still display transcriptional memory during a second stimulation. qRT-PCR results show that the secondary response in siPML-treated cells was impaired relative to that observed in si-scrambled-treated counterparts (Fig. 6C). The magnitude of the secondary response of siPML-treated cells resembled that of a primary IFN-γ response. In contrast to the above, reinduction of either PML or CIITA transcription was not significantly affected (Fig. 6D and E). These results support a direct role of PML in the preservation of the H3K4me2 epigenetic mark on the promoter and the generation of memory in the transcription of DRA.

DISCUSSION

Although the events that are essential for the signal inducible gene expression in terms of transcriptional complex assembly and activation have been well studied in many systems, little is known about the long-term alterations that follow a transient transcriptional burst and the way they may influence response to future activation signals. Epigenetic marks and the mechanism of imposing them are good candidates for long-term effects that modulate transcriptional responses.

Accordingly, MHCII gene expression in relation to the role of the enhanceosome, various cofactors and CIITA have been studied in detail (58). In the present study we investigated long-term alterations in epigenetic marks and locus configuration that accompany past gene activation and how they affect secondary response. We show that a primary IFN induced transcriptional response generates long-term sensitization state (priming) characterized by a more robust secondary response. We propose that priming is an adaptive memory-like process that may be of more general importance in various types of secondary signal regulated gene expression.

In the primed state, the MHCII promoter retains accessible chromatin and high histone H3K4 dimethylation maintained through at least four cell divisions. Persistent methyltransferase activity at the promoter may thus account for prevention of methylation decay upon DNA replication and deposition of new histone molecules. H3K4 methylation has generally been correlated with an active chromatin state. It has been shown that this methylation mark disrupts binding of the NuRD complex (55), a repressor complex containing deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activity to suppress gene transcription (2). Thus, maintenance of the histone H3K4me2 mark correlates with increased accessibility of the locus in both actively expressing and primed cells and might prevent recruitment of remodeling complexes that would drive the promoter architecture back to its original state after transcription ceases. These results are in line with previously published work demonstrating the role of histone or DNA methylation in memory of signal regulated transcription in the yeast and the human interleukin-2 systems, respectively (29, 31).

Another process that may influence epigenetic state and gene activity is nuclear compartmentalization. Accumulating evidence has established the importance of locus proximity to distinct nuclear compartments in both positive and negative transcriptional control: repression associates with the nuclear or nucleolar periphery, whereas the nuclear pore complex, PML, and nuclear speckles are associated with expression (56). It is thought that nuclear compartments may interact with various cofactors such as epigenetic regulators and influence the short- or long-term activity of genes in their neighborhood. PML-NBs have been intensively studied and linked to various biological processes such as tumor suppression, growth, apoptosis, antiviral defense, protein degradation, senescence, and immune response and transcription (5). PML knockout mice have impaired retinoic acid action, are prone to tumor formation and infections (52), and show higher proliferation but lower differentiation of neural progenitors (36) and increased cycling and exhaustion of hematopoietic stem cells (18a). It has been proposed that by regulating availability or activity of regulatory factors, PML limits strong signal outputs (18b). Although part of these diverse effects may be mechanistically similar, the PML heterogeneous morphology, composition, and preferential interactions imply distinct functions of the different PML splicing isoforms (3).

PML proteins are themselves IFN inducible and, although their dynamics increase during mitosis, a subset of mitotic PML (MAPP) remain associated with mitotic chromosomes (8, 12) and may serve as nucleation sites for reestablishing PML structure and function in the next G1 phase.

Based on the findings described above, we chose to investigate whether PML can also function as a determinant of transcriptional memory in the MHC-II system. We show that IFN-γ induction, as well as priming, is accompanied by a locus-specific increased relocation closer to PML bodies. Earlier observations point to nonrandom PML locus proximity and linked PML bodies with actively transcribed loci (20, 42). The present simulation analysis also supports a clustered rather than a random PML locus spacing model. IFN-γ-induced expression is associated with enhanced and prolonged clustering. Thus, the PML action on both the ongoing transcription and the efficiency of restimulation may be mediated via long-term locus PML proximity. Increased proximity of the MHCII locus to PML bodies upon activation may bring it in close contact with a number of transcriptional coactivators to facilitate transcription. The fact that not all alleles associate with PML-NBs at any time is reminiscent of the observation that IFN activation increases the level of the MHCII loci that protrude from chromosome 6 territory from ca. 10 to 35% of the gene alleles (9, 50). It is likely that not all alleles in a cell respond to IFN-γ. Stochastic gene expression has been reported in the case of the IFNb1 gene upon virus infection (1). Alternatively, interactions may be dynamic so in fixed cells a fraction of the loci colocalize with PML at any time. We found that the H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase MLL partly colocalizes with PML bodies upon IFN-γ treatment. We also show that IFN-γ induces the expression of various PML isoforms, one of which, type IV, may recruit MLL via its interaction with one of its subunits, namely, WDR5. This interaction is maintained even after four cell divisions. These results demonstrate for the first time that two IFN-γ-induced regulators, the short-lived CIITA and the long-lived PML, act in concert to regulate both active transcription and transcriptional memory of the MHCII genes.

By overexpressing PML isoforms and by siRNA-mediated knockdown, we have shown a positive role of PML on the primary and secondary (memory type) MHCII transcriptional response to IFN-γ and provide a link between PML isoform abundance modulation, locus proximity, and high H3K4me2 levels.

We have also found that the MHCII locus subnuclear localization and chromatin state are inherited through four cell generations after termination of the IFN-γ-induced transcriptional activity. Although histone H3 K4 trimethylation marks current transcription and is probably coordinated by a still-novel function of the integrator CIITA, we show that maintenance of K4 dimethylation is a signature of both the past transcription state of the gene and an indicator of priming that is manifested by enhanced responsiveness upon new exposure to the inducer. The PML-DRA locus proximity and the PML-MLL interactions through several cell generations may contribute to this phenomenon. We propose that IFN-induced PML bodies recruit MLL or its components to modulate their neighborhood in a way that favors both primary transcription and the maintenance of a poised state that enhance the response to future activation signaling. These data link the mechanism of epigenetic inheritance with the altered locus topology and show that PML bodies as sites of epigenetic regulation (48) are important in signal-mediated adaptive processes and the maintenance of poised gene states.

It is tempting to speculate that the establishment of a sensitized chromatin state of the MHCII locus could be important to the immune response under limiting amounts of cytokines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a HERAKLEITOS grant from the Hellenic Ministry of Education and intramural IMBB funding.

We thank I. Talianidis and H. de Thé for plasmids, C. Spilianakis for expert technical advice and comments, I. Aifantis and A. Kretsovali for critical comments, and G. Vretzos for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apostolou, E., and D. Thanos. 2008. Virus Infection Induces NF-κB-dependent interchromosomal associations mediating monoallelic IFN-β gene expression. Cell 134:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, P. B., and W. Horz. 2002. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:247-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beech, S. J., K. J. Lethbridge, N. Killick, N. McGlincy, and K. N. Leppard. 2005. Isoforms of the promyelocytic leukemia protein differ in their effects on ND10 organization. Exp. Cell Res. 307:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beresford, G. W., and J. M. Boss. 2001. CIITA coordinates multiple histone acetylation modifications at the HLA-DRA promoter. Nat. Immunol. 2:652-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernardi, R., and P. P. Pandolfi. 2007. Structure, dynamics and functions of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:1006-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brickner, D. G., I. Cajigas, Y. Fondufe-Mittendorf, S. Ahmed, P. C. Lee, J. Widom, and J. H. Brickner. 2007. H2A Z-mediated localization of genes at the nuclear periphery confers epigenetic memory of previous transcriptional state. PLoS Biol. 5:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno, S., F. Ghiotto, F. Fais, M. Fagioli, L. Luzi, P. G. Pelicci, C. E. Grossi, and E. Ciccone. 2003. The PML gene is not involved in the regulation of MHC class I expression in human cell lines. Blood 101:3514-3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, T. R. 1988. Re-evaluation of HeLa, HeLa S3, and HEp-2 karyotypes. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 48:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christova, R., T. Jones, P. J. Wu, A. Bolzer, A. P. Costa-Pereira, D. Watling, I. M. Kerr, and D. Sheer. 2007. P-STAT1 mediates higher-order chromatin remodeling of the human MHC in response to IFN-γ. J. Cell Sci. 120:3262-3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark, P., and F. Evans. 1979. Generalization of a nearest neighbor measure of dispersion for use in K dimensions. Ecology 60:316-317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford, B. D., and J. L. Hess. 2006. MLL core components give the green light to histone methylation. ACS Chem. Biol. 1:495-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellaire, G., C. H. Eskiw, H. Dehghani, R. W. Ching, and D. P. Bazett-Jones. 2006. Mitotic accumulations of PML protein contribute to the re-establishment of PML nuclear bodies in G1. J. Cell Sci. 119:1034-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doucas, V., M. Tini, D. A. Egan, and R. M. Evans. 1999. Modulation of CREB binding protein function by the promyelocytic (PML) oncoprotein suggests a role for nuclear bodies in hormone signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:2627-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand, B., P. Sperisen, P. Emery, E. Barras, M. Zufferey, B. Mach, and W. Reith. 1997. RFXAP, a novel subunit of the RFX DNA binding complex is mutated in MHC class II deficiency. EMBO J. 16:1045-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontes, J. D., B. Jiang, and B. M. Peterlin. 1997. The class II transactivator CIITA interacts with the TBP-associated factor TAFII32. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2522-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontes, J. D., S. Kanazawa, D. Jean, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Interactions between the class II transactivator and CREB binding protein increase transcription of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:941-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster, S. L., D. C. Hargreaves, and R. Medzhitov. 2007. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature 447:972-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gialitakis, M., A. Kretsovali, C. Spilianakis, L. Kravariti, J. Mages, R. Hoffmann, A. K. Hatzopoulos, and J. Papamatheakis. 2006. Coordinated changes of histone modifications and HDAC mobilization regulate the induction of MHC class II genes by trichostatin A. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:765-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Ito, K., R. Bernardi, A. Morotti, S. Matsuoka, G. Saglio, Y. Ikeda, J. Rosenblatt, D. E. Avigan, J. Teruya-Feldstein, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2008. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature 453:1072-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b.Ito, K., R. Bernardi, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2009. A novel signaling network as a critical rheostat for the biology and maintenance of the normal stem cell and the cancer-initiating cell. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19:51-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanazawa, S., T. Okamoto, and B. M. Peterlin. 2000. Tat competes with CIITA for the binding to P-TEFb and blocks the expression of MHC class II genes in HIV infection. Immunity 12:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiesslich, A., A. von Mikecz, and P. Hemmerich. 2002. Cell cycle-dependent association of PML bodies with sites of active transcription in nuclei of mammalian cells. J. Struct. Biol. 140:167-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kretsovali, A., T. Agalioti, C. Spilianakis, E. Tzortzakaki, M. Merika, and J. Papamatheakis. 1998. Involvement of CREB binding protein in expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes via interaction with the class II transactivator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6777-6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar, P. P., O. Bischof, P. K. Purbey, D. Notani, H. Urlaub, A. Dejean, and S. Galande. 2007. Functional interaction between PML and SATB1 regulates chromatin-loop architecture and transcription of the MHC class I locus. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kundu, S., P. J. Horn, and C. L. Peterson. 2007. SWI/SNF is required for transcriptional memory at the yeast GAL gene cluster. Genes Dev. 21:997-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavau, C., A. Marchio, M. Fagioli, J. Jansen, B. Falini, P. Lebon, F. Grosveld, P. P. Pandolfi, P. G. Pelicci, and A. Dejean. 1995. The acute promyelocytic leukaemia-associated PML gene is induced by interferon. Oncogene 11:871-876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, C. K., Y. Shibata, B. Rao, B. D. Strahl, and J. D. Lieb. 2004. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat. Genet. 36:900-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macville, M., E. Schrock, H. Padilla-Nash, C. Keck, B. M. Ghadimi, D. Zimonjic, N. Popescu, and T. Ried. 1999. Comprehensive and definitive molecular cytogenetic characterization of HeLa cells by spectral karyotyping. Cancer Res. 59:141-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milne, T. A., S. D. Briggs, H. W. Brock, M. E. Martin, D. Gibbs, C. D. Allis, and J. L. Hess. 2002. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol. Cell 10:1107-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mudhasani, R., and J. D. Fontes. 2005. Multiple interactions between BRG1 and MHC class II promoter binding proteins. Mol. Immunol. 42:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murayama, A., K. Sakura, M. Nakama, K. Yasuzawa-Tanaka, E. Fujita, Y. Tateishi, Y. Wang, T. Ushijima, T. Baba, K. Shibuya, A. Shibuya, Y. Kawabe, and J. Yanagisawa. 2006. A specific CpG site demethylation in the human interleukin 2 gene promoter is an epigenetic memory. EMBO J. 25:1081-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagarajan, U. M., P. Louis-Plence, A. DeSandro, R. Nilsen, A. Bushey, and J. M. Boss. 1999. RFX-B is the gene responsible for the most common cause of the bare lymphocyte syndrome, an MHC class II immunodeficiency. Immunity 10:153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng, H. H., F. Robert, R. A. Young, and K. Struhl. 2003. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11:709-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng, R. K., and J. B. Gurdon. 2008. Epigenetic memory of an active gene state depends on histone H3.3 incorporation into chromatin in the absence of transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:102-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozsolak, F., J. S. Song, X. S. Liu, and D. E. Fisher. 2007. High-throughput mapping of the chromatin structure of human promoters. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:244-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker, D. C. 1993. T-cell-dependent B-cell activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:331-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petesch, S. J., and J. T. Lis. 2008. Rapid, transcription-independent loss of nucleosomes over a large chromatin domain at Hsp70 loci. Cell 134:74-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Regad, T., C. Bellodi, P. Nicotera, and P. Salomoni. 2009. The tumor suppressor Pml regulates cell fate in the developing neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 12:132-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reith, W., S. LeibundGut-Landmann, and J. M. Waldburger. 2005. Regulation of MHC class II gene expression by the class II transactivator. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:793-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reith, W., and B. Mach. 2001. The bare lymphocyte syndrome and the regulation of MHC expression. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:331-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rybtsova, N., E. Leimgruber, Q. Seguin-Estevez, I. Dunand-Sauthier, M. Krawczyk, and W. Reith. 2007. Transcription-coupled deposition of histone modifications during MHC class II gene activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:3431-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnappauf, F., S. B. Hake, M. M. Camacho-Carvajal, S. Bontron, B. Lisowska-Grospierre, and V. Steimle. 2003. N-terminal destruction signals lead to rapid degradation of the major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator CIITA. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:2337-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoenborn, J. R., M. O. Dorschner, M. Sekimata, D. M. Santer, M. Shnyreva, D. R. Fitzpatrick, J. A. Stamatoyannopoulos, and C. B. Wilson. 2007. Comprehensive epigenetic profiling identifies multiple distal regulatory elements directing transcription of the gene encoding interferon-gamma. Nat. Immunol. 8:732-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiels, C., S. A. Islam, R. Vatcheva, P. Sasieni, M. J. Sternberg, P. S. Freemont, and D. Sheer. 2001. PML bodies associate specifically with the MHC gene cluster in interphase nuclei. J. Cell Sci. 114:3705-3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spilianakis, C., A. Kretsovali, T. Agalioti, T. Makatounakis, D. Thanos, and J. Papamatheakis. 2003. CIITA regulates transcription onset viaSer5-phosphorylation of RNA Pol II. EMBO J. 22:5125-5136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spilianakis, C., J. Papamatheakis, and A. Kretsovali. 2000. Acetylation by PCAF enhances CIITA nuclear accumulation and transactivation of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8489-8498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stadler, M., M. K. Chelbi-Alix, M. H. Koken, L. Venturini, C. Lee, A. Saib, F. Quignon, L. Pelicano, M. C. Guillemin, C. Schindler, et al. 1995. Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene 11:2565-2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steimle, V., B. Durand, E. Barras, M. Zufferey, M. R. Hadam, B. Mach, and W. Reith. 1995. A novel DNA-binding regulatory factor is mutated in primary MHC class II deficiency (bare lymphocyte syndrome). Genes Dev. 9:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steimle, V., L. A. Otten, M. Zufferey, and B. Mach. 1993. Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or bare lymphocyte syndrome). Cell 75:135-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torok, D., R. W. Ching, and D. P. Bazett-Jones. 2009. PML nuclear bodies as sites of epigenetic regulation. Front. Biosci. 14:1325-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viret, C., and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 1999. MHC and T-cell development. Rev. Immunogenet. 1:91-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volpi, E. V., E. Chevret, T. Jones, R. Vatcheva, J. Williamson, S. Beck, R. D. Campbell, M. Goldsworthy, S. H. Powis, J. Ragoussis, J. Trowsdale, and D. Sheer. 2000. Large-scale chromatin organization of the major histocompatibility complex and other regions of human chromosome 6 and its response to interferon in interphase nuclei. J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt. 9):1565-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, J., C. Shiels, P. Sasieni, P. J. Wu, S. A. Islam, P. S. Freemont, and D. Sheer. 2004. Promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies associate with transcriptionally active genomic regions. J. Cell Biol. 164:515-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, Z. G., L. Delva, M. Gaboli, R. Rivi, M. Giorgio, C. Cordon-Cardo, F. Grosveld, and P. P. Pandolfi. 1998. Role of PML in cell growth and the retinoic acid pathway. Science 279:1547-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yano, T., T. Nakamura, J. Blechman, C. Sorio, C. V. Dang, B. Geiger, and E. Canaani. 1997. Nuclear punctate distribution of ALL-1 is conferred by distinct elements at the N terminus of the protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:7286-7291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zacharioudakis, I., T. Gligoris, and D. Tzamarias. 2007. A yeast catabolic enzyme controls transcriptional memory. Curr. Biol. 17:2041-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zegerman, P., B. Canas, D. Pappin, and T. Kouzarides. 2002. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation disrupts binding of nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) repressor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11621-11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao, R., M. S. Bodnar, and D. L. Spector. 2009. Nuclear neighborhoods and gene expression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19:172-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zika, E., L. Fauquier, L. Vandel, and J. P. Ting. 2005. Interplay among coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1, CBP, and CIITA in IFN-gamma-inducible MHC-II gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16321-16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zika, E., and J. P. Ting. 2005. Epigenetic control of MHC-II: interplay between CIITA and histone-modifying enzymes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17:58-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.