Abstract

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) fusion with cells requires the gD, gB, and gH/gL glycoprotein quartet. gD serves as a receptor binding glycoprotein. gB and gH/gL execute fusion in an as-yet-unclear manner. To better understand the role of gH/gL in HSV entry, we produced a soluble version of gH/gL carrying a One-STrEP tag (gHt.st/gL). Previous findings implicated integrins as possible ligands to gH/gL (C. Parry et al., J. Gen. Virol. 86:7-10, 2005). We report that (i) gHt.st/gL bound a number of cells in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations similar to those required for the binding of soluble gB or gD. (ii) gHt.st/gL inhibited HSV entry at the same concentrations required for binding. It also inhibited cell-cell fusion in transfected cells. (iii) The absence of β3 integrin did not prevent the binding of gHt.st/gL to CHO cells and infection inhibition. Conversely, integrin-negative K562 cells did not acquire the ability to bind gHt.st/gL when hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin. (iv) Constitutive expression of wild-type gH/gL (wt-gH/gL) restricted infection in all of the cell lines tested, a behavior typical of glycoproteins which bind cellular receptors. The extent of restriction broadly paralleled the efficiency of gH/gL transfection. RGD motif mutant gH/gL could not be differentiated from wt-gH with respect to restriction of infection. Cumulatively, the present results provide several lines of evidence that HSV gH/gL interacts with a cell surface cognate protein(s), that this protein is not necessarily an αVβ3 integrin, and that this interaction is required for the process of virus entry/fusion.

Entry of herpes simplex virus (HSV) into the cell occurs by fusion of the virion envelope with a cell membrane, either the plasma or the endocytic membrane, and requires the essential quartet made of gD, gB, and gH/gL (45, 58; see also reference 14). gD serves as the receptor binding glycoprotein able to interact with at least three alternative receptors, nectin1, HVEM (herpesvirus entry mediator), and modified heparan sulfate and consequently is the major determinant of HSV tropism (21, 26, 41, 54). gD also serves as a sensor and trigger of fusion; i.e., it senses that virions have reached a receptor-positive cell and signals to the downstream glycoproteins gB and gH/gL that fusion between the virion envelope and the cell membrane needs to be executed (19).

The gD crystal structure shows an immunoglobulin (Ig)-folded core bracketed by N- and C-terminal extensions (16). The HVEM binding site in gD maps to residues 1 to 32; it is unstructured in unliganded gD and forms a hairpin in HVEM-bound gD. Triggering of fusion requires gD sequences, named the profusion domain, located in part in the ectodomain C terminus and in part upstream. How gD triggers fusion is the subject of intense investigations. Biochemical and structural studies indicate that in unliganded gD, the C terminus folds around the gD core and occupies what will be the receptor binding sites (22). At receptor binding, the C terminus is dislodged and makes available the receptor binding sites (39). The more speculative part of the model predicts that the profusion domain activates gB and/or gH/gL (19, 27, 39).

Together, gB and gH/gL constitute the executors of fusion and the conserved fusion apparatus across the Herpesviridae family. The gB structure has been solved in the postfusion conformation and exhibits features typical of fusion glycoproteins, arguing in favor of gB as a fusogen (34). The structure, similar to that of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein, shows a trimer, with a central coiled coil, a bipartite fusion loop protruding from a pleckstrin-like domain, and a crown containing the binding sites for neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (34). The overall structure is conserved among gB orthologs (6). It is unclear whether gB ever adopts a prefusion conformation or undergoes but minor changes relative to the known conformation.

gH and gL form a heterodimer whose structure has not yet been solved. gL is required for gH to adopt its native conformation and to be transported along the exocytic pathway to the plasma membrane (35). Molecular and biochemical characterization shows a net propensity of gH/gL to interact with membranes. In particular, gH carries a predicted alpha helix critical for fusion; downstream of it are two predicted heptad repeats potentially able to form a coiled-coil as well as membrane-to-interface regions (24, 28-30).

Key questions about HSV entry are the following. Why does HSV fusion require gB and gH/gL and not a single glycoprotein, as is the case for most viruses? What are the respective roles of gH/gL and gB in fusion? Do gB and gH/gL interact with cellular cognate proteins in order to carry out entry/fusion? Protein-protein interaction studies showed that gB and gH/gL interact with gD independently of one another (2, 3), arguing against their stepwise recruitment to gD, as predicted by the hemifusion model (56). In addition, gB and gH/gL interact with each other both in the absence and in the presence of gD (4, 27). Across the Herpesviridae family, several cell surface proteins interact with gB, with gH/gL, or with gH/gL-interacting proteins like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) gp42, human herpesvirus 6 gO, gQ1, and gQ2, and human cytomegalovirus UL128-131. Examples are the major histocompatibility complex as a cellular partner of EBV gp42 (62), paired Ig-like receptor α and myelin-associated glycoprotein as partners of HSV gB (51, 57), CD46 as a partner of HHV-6 gH/gO/gQ1/gQ2 (42), and members of the integrin family as partners of human cytomegalovirus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, and EBV gH/gL (1, 18, 61). It was reported that a soluble form of gH/gL immobilized on plastic facilitates the adhesion of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transiently overexpressing a number of integrins, in particular, αVβ3 integrin (47). Whether this reflects a direct interaction of gH/gL with integrins or with unrelated molecules unmasked as a consequence of integrin expression has not been determined. Integrins are cell surface heterodimeric glycoproteins that contribute to a variety of functions, including cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion and induction of signal transduction pathways (23). Heterodimers are made of an α and a β subunit. The pattern of heterodimer formation is nonrandom; thus, αV forms dimers with β1, β3, β5, β6, and β8 subunits. Some integrins are frequently expressed on epithelial and endothelial cells, whereas others are restricted to specialized cells.

In the present study, we produced a soluble truncated form of HSV gH/gL, purified by means of a One-STrEP tag (gHt/gL), designated gHt.st/gL. We report that (i) gHt.st/gL bound to cell surfaces, in most cases in a saturable manner, independently of the presence of β3 integrins; (ii) gHt.st/gL inhibited HSV infection and cell-cell fusion mediated by the transfected glycoprotein quartet; and (iii) expression of full-length gH/gL restricted infection. Altogether, the results provide several lines of evidence that HSV gH/gL interacts with a cell surface partner to carry out entry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

African green monkey kidney (Vero), COS, HT29, 293T, human foreskin fibroblast 14 (HFF14), rabbit skin (RS), baby hamster kidney (BHK), and J (a derivative of BHK-TK− cells lacking any HSV receptor) (21) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5 to 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). CHO, colon carcinoma SW480, K562, and Friend leukemia murine cells were grown in F12 medium, L15 medium, and Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, respectively. sog9 cells are deficient in the synthesis of heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate (31). The growth medium for K562αVβ3 (11) and HT29αVβ3 contained 750 μg/ml neomycin G418. R8102, a recombinant HSV type 1 (HSV-1) strain expressing lacZ under the control of the α27 promoter was previously described (21).

Plasmids.

Expression plasmids encoding HSV-1 gD, gB, gH, gL, nectin-1 (pCF18), HER-2 (a modified version of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2), and yellow fluorescent protein-Venus (YFPVenus), all under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter, were previously described (5, 21, 43, 49). Plasmid pCAGT7 contains the T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of the CAG promoter, and the pT7EMCVLuc plasmid expresses firefly luciferase under the control of the T7 promoter (48). αV and β3 integrin expression plasmids were previously described (11). pcDNA3.1(−)Myc-His/Lac, pMT/BiP/V5-His, and pCoBlast were from Invitrogen.

Antibodies.

MAb H1817 to gB recognizes a conformation-independent N-terminal epitope; it was purchased from the Goodwin Institute (FL). MAbs 52S and 53S recognize gH and gH/gL, respectively; both are directed to conformation-dependent epitopes and neutralize virion infectivity (53). Polyclonal antibody (PAb) to gH/gL and PAb R45 to gD were generous gifts from H. Browne and G. H. Cohen and R. Eisenberg, respectively. MAbs L230 (function blocking) and AP3 directed to αV integrin and β3 integrin, respectively, were previously described (7, 44). MAb LM609 to αVβ3 integrin heterodimer is a function-blocking antibody from Chemicon (17). Strep-Tactin-HRP (horseradish peroxidase) conjugate was from IBA GmbH (Göttingen). MAb A10 to gHt.st/gL was derived by standard techniques by PRIMM (Milan). It is positive to infected cell gH/gL by immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and blocks virion infectivity (A. Cerretani and G. Campadelli-Fiume, unpublished data). PAb to HVEM and MAb R1.302 to nectin1 were gifts from G. H. Cohen and R. Eisenberg and from M. Lopez, respectively.

Soluble glycoproteins.

Soluble gB730t and gDΔ290-299t (herein referred to as gD290t) were generous gifts from G. H. Cohen and R. Eisenberg (9, 46). One-STrEP-tagged green fluorescent protein (GFPst) was provided by IBA GmbH (Göttingen).

Expression and purification of soluble gHt.st/gL in insect cells.

The overall strategy was to clone the appropriate sequence of the gH ectodomain (amino acids [aa] 21 to 793) into the pMT/BiP/V5-His vector (Invitrogen) under the control of the Drosophila metallothionein promoter and the BiP secretion signal sequence. Two series of constructs, each encoding gH and gL, were generated. The series I constructs were as follows. Downstream of aa 793, the construct carried, in order, the factor Xa cleavage site (for removal of downstream tags), the 5E1 epitope (55), a Ser-Ala linker, and the One-STrEP tag consisting of two tandem One-STrEP tags and an intervening Ser-Gly linker. This construct was named p-gHt.st. It was generated by amplification of gH sequences from HSV-1(F) DNA with oligonucleotides gH_NotI_forw (5′-GCG TGG GGC GGC CGC CAC GAC TGG ACT GAG C-3′) and gH_XhoI_rev (5′-CCG TCA TTC ATT TGC TAG CCC TCG AGC ACG CAG CCC-3′). The NotI-XhoI-digested amplimer was cloned into the p-MT/BiP/V5-His vector. The recombinant plasmid was then digested with NheI (within the gH open reading frame [ORF]) and XhoI and religated with an in vitro-generated DNA which cumulatively encoded factor Xa, the 5E1 epitope, and the One-STrEP tag. The latter was obtained by extensions of two oligonucleotides, One-strepNheI_forw (5′-GCC GCG CTA GCC ATC GAA GGG CGA AGT CGA CCA GGA AGC ACT ACA CCC TCT GGG AAC TCT GCA AGG TAT GGG AAT AAC ACA AGC GCT TGG AGC CAC CCG CAG TTC G-3′) and One-StrepXhoI_rev (5′-GCC GGC TCG AGT CAT TTT TCG AAC TGC GGG TGG CTC CAC GAT CCA CCT CCC GAT CCA CCT CCG GAA CCT CCA CCT TTC TCG AAC TGC GGG TGG CTC CAA GC-3′). The One-strepNheI_forw oligonucleotide contained a silent SalI site for screening. The gL-expressing construct (gLV5His) was generated by cloning the entire gL ORF, except the first 19 aa that form the signal sequence, which were replaced with the BiP signal sequence contained in the plasmid. The gL sequence was amplified from HSV-1(F) DNA by means of oligonucleotides gL_Eco_forw (5′-GTG TGT GAA TCC GGG CTT GCC TTC AAC CG-3′) and gL_NotI-rev (5′-CGG CGC CTC TTG CGG CCG CCT CGA CGG AAA CCC G-3′), which introduced a suppression mutation at the gL stop codon. The EcoRI-NotI-digested amplimer was cloned into the p-MT/BiP/V5-His vector. S2 cells were transfected with 13 μg of p-gHt.st, 6 μg of gLV5His, and 1 μg of pCoBlast (Invitrogen). Five days after transfection, cells were selected with blasticidin (5 to 10 μg/ml). The series II constructs were as follows. The gH-expressing construct was generated by PCR amplification from a codon-optimized synthetic gene encoding HSV-1 gH. The BglII and ApaI sites were used to clone it into the pMT/BiP/V5-His vector. The gL-expressing construct was generated by cloning the entire gL ORF, except the first 19 aa constituting the signal sequence, which were replaced with the BiP signal sequence contained in the vector. It was generated by PCR amplification from a codon-optimized synthetic gene encoding HSV-1 gL (aa 20 to 222). The BglII and ApaI sites were used to clone it into the pMT/BiP/V5-His vector, and two stop codons were used after aa 222 to make the construct tagless. All constructs were sequenced for accuracy. S2 cells (5 × 106) were transfected with 2 μg of p-gHt.st, 2 μg of gL, and 10 ng of pCoHygro (Invitrogen) using the Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen). Three days after transfection, S2 cells were selected with hygromycin (400 μg/ml). The selected cell lines were checked for gHt.st/gL expression after induction with CuSO4 in serum-free X-press medium (Lonza). Medium was harvested at 7 to 9 days after induction. Protein purification by means of Strep-Tactin columns was performed according to the IBA protocol. The yield of protein was in the range of 1 to 7 mg/liter of medium. To determine the size and stoichiometry of purified gHt.st/gL, the protein was subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl. The retention time of the gHt.st/gL protein complex was used for comparison to globular proteins in gel filtration standards (Bio-Rad) for estimation of complex size. Static light scattering was carried out over the gHt.st/gL peak during elution from the Superdex 200 column to determine the molecular weight of purified gHt.st/gL.

ELISA.

The reactivity of gHt.st/gL to MAbs 52S, 53S and A10 was measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). gHt.st/gL or fetuin (negative control) was immobilized on 96-well trays at a concentration of 0.3 μM in bicarbonate buffer for 16 h at 4°C. Unspecific binding sites were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h at 37°C. Serial dilution of MAbs 52S, 53S, and A10 (from 1:100 to 1:800) were added to the wells in PBS containing 1% BSA and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Excess antibodies were removed, and the bound antibodies were reacted with anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to peroxidase. Binding was detected by incubation with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma Chemical Company) at 0.5 mg/ml and reading the optical density at 490 nm.

IFA and flow cytometry.

Expression of αVβ3 integrin was monitored by IFA in paraformaldehyde-fixed cells by incubation with MAb LM609 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Pictures were taken in a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM 1200F digital camera. For flow cytometry analysis, 293T cells were harvested 24 h after transfection of αV and β3 integrin plasmids. K562 and K562αVβ3 were seeded 24 h prior to analysis. Cells were washed once with PBS and once with PBS containing 10% FBS and allowed to react with MAb L230 (to αV integrin), MAb AP3 (to β3 integrin), PAb to HVEM, or MAb R1.302 to nectin1 for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were washed three times with PBS and reacted with phycoerythrin (PE)- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled secondary antibodies (Dako and Sigma Chemical Company). Control cells were incubated with secondary antibodies. Cells were analyzed with a FACScalibur cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For each sample, a minimum of 20,000 cells were acquired in list mode.

Binding of gHt.st/gL to cells by cell ELISA (CELISA) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Cells grown in 96-well trays were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with serial dilutions of soluble glycoproteins in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 30 mM HEPES (9), washed three times with the same buffer, and further incubated for 1 h a 4°C with PAb R45, MAb H1817, or HRP-conjugated MAb to the One-STrEP tag (Strep-Tactin) for detection of gD, gB, gHt.st/gL or GFPst, respectively. Cells were again rinsed three times with cold PBS and incubated, when necessary, for 1 h a 4°C with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Following three additional rinsings, cells were reacted with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma Chemical Company) at 0.5 mg/ml; the optical density was read at 490 nm. To detect the binding of gHt.st/gL to cells at different pHs, 3-hydroxy-5,5-dimethyl-4-[4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]furan-2(5H)-one was brought to the indicated pH by means of MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid]. Suspension CELISAs for K562, K562αVβ3, and 293T cells were done essentially as described above, except that the cells were kept in suspension and rinsings were performed by low-spin centrifugation. For flow cytometry analysis, 293T cells were harvested 24 h after transfection with αV and β3 integrin plasmids. K562 and K562αVβ3 were seeded 24 h prior to analysis. Cells were washed once with PBS and once with PBS containing 10% FBS and then allowed to react with 2 μM gHt.st/gL in 100 μl of DMEM containing 5% FBS and 30 mM HEPES for 1 h a 4°C. Cells were washed three times with PBS and reacted with MAb 52S (1:400) in PBS containing 10% FBS for 1 h a 4°C. Finally, cells were washed twice and incubated for 45 min at 4°C with PBS plus 10% FBS and a PE-coupled anti-mouse secondary antibody (Dako). Control cells were incubated with MAb 52S and the secondary antibody. Cells were analyzed as described above.

Inhibition of HSV infection by gHt.st/gL.

Inhibition of HSV infection by gHt.st/gL was done as previously detailed for gBt (9). Briefly, cells in 96-well trays were preincubated with the indicated amounts of gHt.st/gL, heat-inactivated gHt.st/gL, or GFPst diluted in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 30 mM HEPES for 1 h at 37°C. The appropriate amount of R8102 (3 PFU/cell) in 5 μl was then added for a further 90 min of incubation at 37°C. The viral inoculum was removed, and cells were rinsed twice with PBS, once with an acidic wash, and twice with PBS again. Finally, cells were overlaid with DMEM containing the soluble glycoproteins plus 1% FBS and incubated for 8 h. In the experiments where the effect of MAb 52S on gHt.st/gL-mediated inhibition of virus entry was tested, MAb 52S was first immobilized on protein A-Sepharose; gHt.st/gL was then reacted with immobilized MAb 52S. The nonabsorbed material was assayed for inhibition of virus infection. As a negative control, gHt.st/gL was allowed to react with an irrelevant antibody (MAb HD1 to gD) and subjected to the same procedure as described above. The extent of infection was monitored through β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity at 405 nm (21), by means of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, or by in situ staining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside. A value of 100% represents data obtained with infected cells not exposed to soluble glycoproteins.

Inhibition of cell-cell fusion by gHt.st/gL.

The luciferase-based cell-cell fusion assay with 293T cells was performed as described previously (48), by using the Luciferase Assay System from Promega (Florence, Italy). The total amounts of transfected plasmid DNAs were made equal by addition of HER-2 plasmid DNA. At 24 h after transfection, target cells were seeded at a 1:1 ratio with effector cells in the presence of gHt.st/gL or GFPst at 0.8 μM each. Results are expressed as the average of triplicates ± the standard deviation. The cell-cell fusion assay with COS cells was performed as described previously (58); gHt.st/gL or GFPst (0.8 μM) was added 8 h after transfection.

Transfection of cells.

293T cells transiently expressing αVβ3 integrin (293TαVβ3) were transfected with αV and β3 integrin-encoding plasmids (6 μg of each plasmid DNA per T75 flask) by means of Arrest-in (Celbio, Milan). As a negative control, cells were transfected with 12 μg of a HER2-encoding plasmid. At 24 h, transfected cells were seeded into 96-well trays or onto glass coverslips. Alternatively, they were used for FACS. Transfection of J or CHO cells with nectin1, with or without αVβ3 integrin, was performed in the same way. Briefly, cells in T75 flasks were transfected with 4 μg of each plasmid DNA by means of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfection mixtures from which αV and β3 integrin plasmids were omitted contained the HER2-encoding plasmid such that the total amount of DNA transfected in each flask remained constant.

HT29 cells hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin (HT29αVβ3).

The HT29αVβ3 cell line was generated by transfection of HT29 cells (in T25 flasks) with 2 μg each of αV and β3 integrin plasmid DNAs by means of Arrest-in (Celbio, Milan). Two days after transfection, cells were exposed to neomycin G418 selection (400 to 800 μg/ml) for 5 days. Individual clones were obtained by limiting dilution and checked for αVβ3 integrin expression by IFA.

Mutagenesis of gH RGD motif.

A form of gH carrying the R176A, G177D, and D178A substitutions in the gH RGD motif (herein named gHRGD>ADA) was derived by site-directed mutagenesis by means of oligonucleotides 5′-CGT CCC TGA CCC CGA AGC TTT GAC GTT CCC GGC GGA CGC CAA CGT GGC GAC GGCG-3′ and 5′-CGC CGT CGC CAC GTT GGC GTC CGC CGG GAA CGT CAA AGC TTC GGG GTC AGG GAC-3′ containing a silent HindIII site for ease of screening, as described previously.

Restriction of infection mediated by full-length gH/gL.

For restriction-of-infection experiments, cells (except J and CHO cells) in T25 flasks were transfected with 1.5 μg DNA each of gH-encoding and gL-encoding plasmids (or a gD-encoding plasmid) plus 1.5 μg of YFPVenus plasmid DNA. The negative control cells were transfected with 4.5 μg of HER2-encoding plasmid DNA. Where indicated, the wild-type gH (wt-gH)-encoding plasmid was replaced with the gHRGD>ADA plasmid. J and CHO cells in T25 flasks were transfected with mixtures containing nectin1, in addition to wt-gH (or gHRGD>ADA), gL, and YFPVenus. Where appropriate, the gH/gL plasmids were replaced with the gD plasmid. Negative control cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of nectin1 plasmid DNA plus 3 μg of HER2-encoding plasmid DNA. Twenty-four hours later, cells were seeded into 96- or 24-well trays on glass coverslips and employed after a further 24 h. Cells on glass coverslips were used to evaluate transgene expression, and those in the 96-well trays were used for infection analysis. The total number of cells present on glass coverslips was detected by staining of nuclei with Hoechst. Cells grown in 96-well trays were infected with R8102 (3 PFU/cell) for 1 h at 37°C. The viral inoculum was removed, and the cells were overlaid with DMEM containing 1% FBS for 16 h. β-Gal activity was measured at 405 nm as described previously (21). A value of 100% represents data obtained with infected cells not exposed to glycoproteins.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from the indicated cell lines with an RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen). After digestion with DNase, total RNA was retrotranscribed with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Roche cDNA synthesis kit). Two sets of primers were employed for αV and β3 integrin amplification, one annealing to the human isoforms and one annealing to the rodent isoforms. They were 5′-TAA AGG CAG ATG GCA AAG GAG T-3′ and 5′-CAG TGG AAT GGA AAC GAT GAG C-3′ for human αV integrin, 5′-CCT TAT ACA ATT TAC TGG CGA GC-3′ and 5′-AAT GCT AGG GTA CAC TTC AAG ACC-3′ for rodent αV integrin, 5′-GAA ATG ATG GGA TTT TAG CAGC-3′ and 5′-TCA TTG CCC CAT ATC TAA TTCC-3′ for human β3 integrin, 5′-GTG AGC TCA TTC CTG GGACC-3′ and 5′-CCT TGG GGC TGC ACT CTT CC-3′ for rodent β3 integrin, and 5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA-3′ and 5′-AGTCA TAGTC CGCCT AGAAG CATTT GCGGT-3′ for β-actin.

RESULTS

Production of gHt.st/gL in insect cells.

Over the past few years, our laboratories have tried several approaches to produce significant amounts of soluble pure gH/gL. These included production through baculoviruses and purification by affinity chromatography with MAbs directed to gH/gL or to heterologous tags (His, 5E1) (55). The approach reported here, based on inducible expression in insect cells and purification through the One-STrEP tag, gave the best results. To generate One-STrEP-tagged gH, appropriate portions of the gH and gL ORFs were cloned into the pMT/BiP/V5/His vector under the control of the metallothionein promoter downstream of the BiP signal sequence for expression and secretion in S2 insect cells. The gH ORF consists of 839 aa; the endogenous gH signal sequence spans aa 1 to 20, and the transmembrane sequence starts at aa 803. The gH ORF portion initially selected spanned aa 21 to aa 793. Downstream of it, we engineered a protease cleavage site and the One-STrEP tag to enable purification of the secreted protein. As a consequence of the engineering, 5 C-terminal aa were lost. The resulting plasmid was named p-gHt.st. The gL ORF consists of 224 aa, with the endogenous signal sequence spanning aa 1 to 18. The selected portion of the gL ORF spanned aa 19 to 223 (gL encodes no transmembrane sequence) and was cloned into the pMT/BiP/V5/His vector. Two series of constructs (I and II) were generated, each expressing gH and gL, respectively. The details are described in Materials and Methods. For series I or series II constructs, S2 cells were cotransfected as detailed in Materials and Methods and selected for blasticidin (5 to 10 μg/ml) or hygromycin (400 μg/ml) resistance, respectively. The selected cells expressed gHt788-strep/gL. We did not observe any difference between gHt.strep/gL from series I and that from series II. Below, we refer to gHt.st/gL, irrespective of series I or II derivation. Insect cell medium was harvested 7 to 10 days after CuSO4 induction. gHt.st/gL was purified to homogeneity, as detected by silver staining (Fig. 1A), by means of Strep-Tactin resin according to the manufacturer (IBA GmbH). Typical yields varied from 1 to 7 mg of protein/liter of medium. The estimated molecular masses of native gHt.st and gL inferred by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were 95 and 28 kDa, respectively. The molecular masses of native gHt.st and gL, measured by SELDI mass spectrometry, were 93.8 kDa and 25.1 or 26.1 kDa, respectively. By comparison with the predicted molecular masses based upon their amino acid sequences (88 kDa and 23 kDa), it is likely that both gHt.st and gL are glycosylated. To determine the size and stoichiometry of the complex, gHt.st/gL was subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column. The protein complex eluted in a single peak with an approximate size of 125 kDa compared to globular protein gel filtration standards (Fig. 1B). This finding suggested that the gHt.st/gL complex likely forms a 1:1 ratio of gHt.st/gL that is predicted to be 120 kDa. To confirm this, static light scattering was carried out over the gHt.st/gL peak during elution to determine that the molecular mass of purified gHt.st/gL was approximately 130 kDa (data not shown).

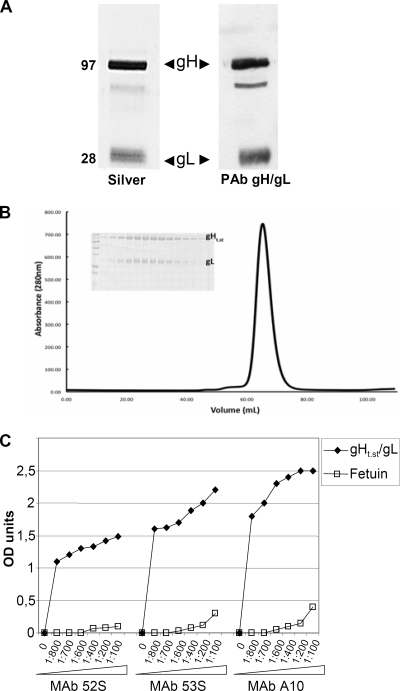

FIG. 1.

Properties of purified gHt.st/gL. (A) Aliquots of gHt.st/gL made in insect cells and purified by means of Strep-Tactin resin according to the manufacturer protocol were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and silver stained (Silver) (left lane) or reacted by Western blotting with a PAb to gH/gL (right lane). The values to the left are molecular sizes in kilodaltons. (B) Size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl. Static light scattering was carried out over the gHt.st/gL peak during elution from the Superdex 200 column to determine the molecular weight of purified gHt.st/gL. The x axis is elution volume in ml, and the y axis is milliunits of absorbance at 280 nm (mAU). Insert, pattern of proteins as seen in denaturing gel electrophoresis with Coomassie blue staining. (C) ELISA reactivity of gHt.st/gL to neutralizing MAbs 52S, 53S, and A10 to gH/gL. gHt.st/gL or fetuin, as a negative control, was immobilized on 96-well plates and allowed to react with increasing dilutions of the MAbs. Reactivity was detected by means of anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to peroxidase, followed by o-phenylenediamine and reading of the optical density (OD) at 490 nm. Each point represents the average of triplicate measurements.

gHt.st/gL exhibits a native conformation.

To verify whether gHt.st/gL exhibits a native conformation, we measured its reactivity to MAbs 52S, 53S, and A10 directed to conformation-dependent epitopes. MAb 52S reacts to a gL-independent epitope, whereas MAb 53S reacts to a gL-dependent epitope (53). MAbs 52S and 53S neutralize virus infection. Figure 1C shows the reactivity of gHt.st/gL to increasing concentrations of MAbs, as measured by ELISA. None of the antibodies exhibited reactivity to an unrelated soluble glycoprotein, fetuin (Fig. 1C).

Properties of cells employed in these studies.

It was reported that a soluble form of gH/gL immobilized on plastic facilitates adhesion of CHO cells transiently overexpressing a number of integrins, in particular, αVβ3 integrin (47). The cells employed in this study were characterized with respect to αVβ3 integrin expression. We also generated cells hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin.

HT29 cells hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin (HT29αVβ3) were generated by transfection of αV and β3 integrin-encoding plasmids and neomycin selection. 293T cells transiently hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin (293TαVβ3) were generated each time by transfection of αV and β3 integrin-encoding plasmids. K562 cells hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin (K562αVβ3) were previously described (11).

αVβ3 integrin expression was detected by RT-PCR and IFA in monolayer cells and by flow cytometry. RNA was extracted from HT29, HT29αVβ3, 293T, 293TαVβ3, SW480, HFF14, K562, K562αVβ3, CHO, J, BHK, and murine Friend erythroleukemia cells (control for rodent αV and β3 integrins), retrotranscribed, and amplified. For both αV and β3 integrins, two set of primers were designed, one annealing to the human isoform and one annealing to the rodent isoform. Results in Fig. 2A show that all of the cells were positive for αV integrin expression, except K562 cells (11). With respect to β3 integrin expression, all of the cells were positive, except CHO and K562 cells.

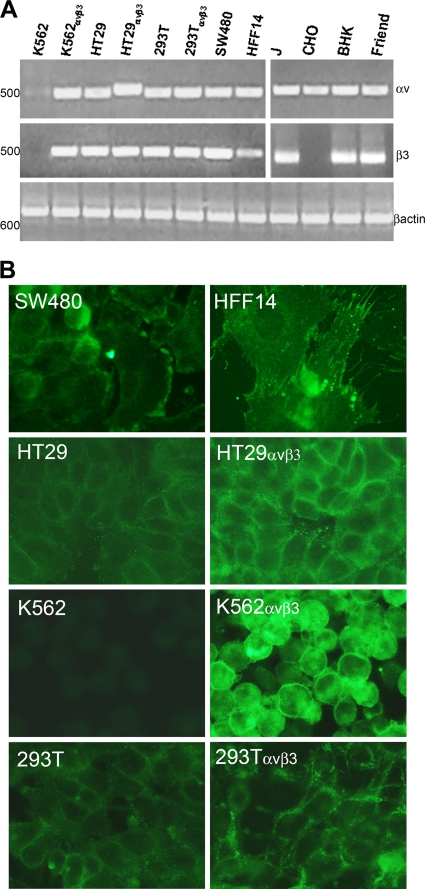

FIG. 2.

Expression of αV and β3 integrin subunits. (A) Detection of αV and β3 integrin transcripts by RT-PCR. The cDNA of the indicated cells was amplified by means of αV integrin or β3 integrin primers annealing to the human (left) or rodent (right) isoform. As a control for RT-PCR, all of the cells were checked for β-actin expression. The values on the left represent the migration positions of 500- or 600-bp markers. (B) IFA detection of αVβ3 integrin by means of MAb LM609. All pictures were taken with the same exposure time by means of a 63× objective. All of the inserts in panel A, except that relative to β3 on the right, were modified by Photoshop software as follows: −35% brightness, +30% contrast. HFF14 insert in panel B: brightness, −20%; contrast, +20%. All of panel B: brightness, +40%; contrast, +100%.

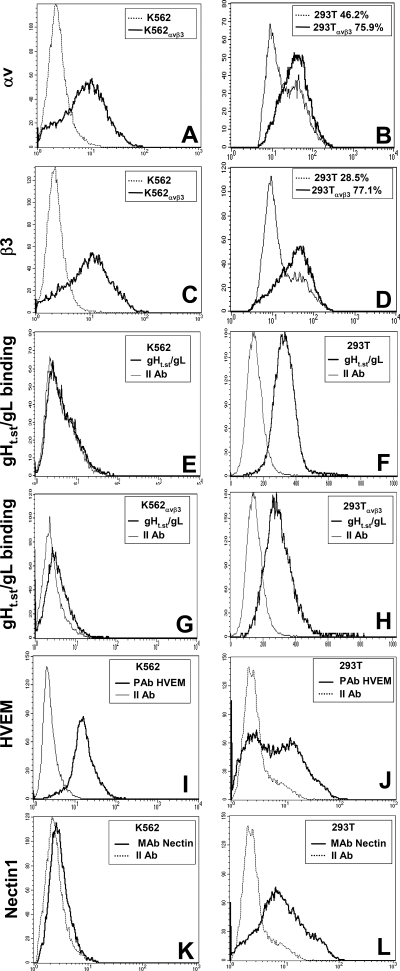

RT-PCR results were validated by IFA and FACS. IFA by means of MAb LM609 (17) to the αVβ3 integrin heterodimer revealed expression in SW480, HFF14, HT29, HT29αVβ3, K562αVβ3, 293T, and 293TαVβ3 cells and no detectable expression in αVβ3 integrin-negative K562 cells, as expected (Fig. 2B). Flow cytometry analysis was performed with antibodies specific to the αV or β3 integrin subunit and confirmed αV and β3 integrin expression in K562αVβ3 cells and not in parental K562 cells (Fig. 3A and C). 293T and 293TαVβ3 cells exhibited αVβ3 integrin expression with both antibodies (Fig. 3B and D). 293T cells transfected with αV and β3 integrins exhibited a somewhat higher expression of each subunit than their wild-type counterparts. Cumulatively, these assays demonstrated that all of the cells under study were positive for αVβ3 integrin; the exceptions were K562 and CHO cells, which were negative for αVβ3 integrin and for β3 integrin, respectively. Because K562 cells were resistant to HSV infection, irrespective of whether or not they hyperexpressed αVβ3 integrin, we further investigated their expression of gD receptors. Figure 3 shows that K562 cells expressed HVEM but not nectin1 (panels I and K), whereas 293T cells, included as controls, expressed both HVEM and nectin1 (panels J and L).

FIG. 3.

Expression of αV and β3 integrin and of HVEM and nectin1 receptors and gHt.st/gL binding as detected by flow cytometry. (A to D) The indicated cells were reacted with MAb L230 to αV integrin (A, B) or MAb AP3 to β3 integrin (C, D). (E to H) The indicated cells were reacted with gHt.st/gL, followed by MAb 52S. (I to L) The indicated cells were reacted with PAb to HVEM (I, J) or MAb R1.302 to nectin1 (K, L). Abscissa, fluorescence intensity.

gHt.st/gL binds to the surface of human and rodent cell lines.

The binding of gHt.st/gL to a number of cells was measured by CELISA and flow cytometry. For CELISA, gHt.st/gL at increasing concentrations was allowed to react with cells grown in 96-well dishes in triplicate at 4°C for 1 h. Binding was detected by means of HRP-conjugated Strep-Tactin. The binding of a soluble form of GFP carrying the One-STrEP tag (GFPst) was detected in parallel. Results in Fig. 4A to F show that gHt.st/gL bound SW480, HFF14, HT29, HT29αVβ3, 293T, and 293TαVβ3 human cells in a dose-dependent manner. Saturation was generally reached at about 1.6 μM gHt.st/gL. No binding was detected with GFPst, testifying to the specificity of gHt.st/gL binding. Soluble forms of gD and gB are known to bind to cells (10, 36). Figure 4A to F shows that gB730t bound to cells at concentrations similar to those of gHt.st/gL. gD290t bound at lower concentrations. Minor variations were observed when gHt.st/gL binding was carried out at lower pHs, namely, pH 6 and pH 5 (Fig. 4G to J). Next, we measured the binding of gHt.st/gL, and for comparison, gB730t and GFPst, to wt-K562 and K562αVβ3 cells. In this case, CELISA was performed with cells in suspension and not in a monolayer. Figure 4K shows that neither K562 nor K562αVβ3 bound gHt.st/gL to a significant degree, whereas both cells bound gB730t. As a control for the suspension CELISA, we used 293T cells in suspension, which bound gHt.st/gL and gB730t, as they did in a monolayer CELISA (Fig. 4, compare panels E to F to panel K). As expected, wt-K562, K562αVβ3, and 293T cells failed to bind GFPst in monolayer and suspension CELISAs.

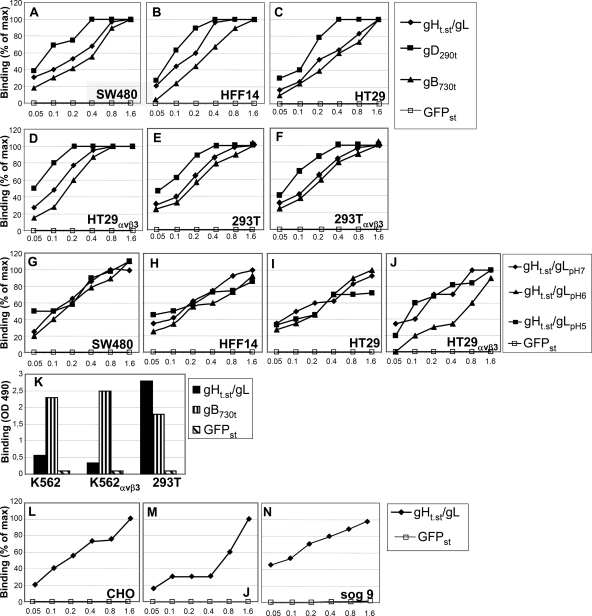

FIG. 4.

CELISA binding of gHt.st/gL to cells. (A to F) gHt.st/gL, gDΔ290-299 (gD290t), gB730t, or GFPst was allowed to react with cells grown in 96-well plates. Binding was detected by means of appropriate antibodies (PAb R45 to gD, MAb H1817 to gB), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies or HRP-conjugated MAb to the One-STrEP tag (Strep-Tactin) for gHt.st/gL or GFPst and the o-phenylenediamine substrate. (G to J) gHt.st/gL or GFPst was reacted with the indicated cells in medium adjusted to pH 7, pH 6, or pH 5. (K) CELISA with K562, K562αVβ3, and 293T cells in suspension. gHt.st/gL, gB730t, or GFPst was reacted with cells as described above, except that the cells were in suspension. Binding was detected as in panels A to F. (L to N) Binding of gHt.st/gL to receptor-negative CHO and J cells or to heparan sulfate- and chondroitin sulfate-negative sog9 cells. Abscissa, μM concentrations.

We examined the binding of gHt.st/gL to CHO and J cells, rodent cells negative for HSV entry receptors. CELISA showed that gHt.st/gL bound either cell type. J cells required higher concentrations of gHt.st/gL than CHO cells and exhibited a likely biphasic curve (Fig. 4L and M).

sog9 cells are deficient in the synthesis of both heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate (31). Figure 4N shows that the binding of gHt.st/gL to sog9 cells was substantially similar to that to other cells, ruling out the possibility that heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate are the molecular partners of gH/gL.

The binding of gHt.st/gL to K562 cells, wild type or expressing αVβ3 integrin, was further analyzed by FACS. Cells were incubated with gHt.st/gL (2 μM) and reacted with MAb 52S. gHt.st/gL failed to bind K562 cells, irrespective of whether they expressed αVβ3 integrin (Fig. 3E and G). 293T cells were included as positive controls and exhibited positive binding of gHt.st/gL (Fig. 3F). When transfected with αV and β3 integrins, the percentage of αV and β3 integrin-positive cells increased by two- to threefold, while the fluorescence intensity exhibited a moderate increase (Fig. 3B and D). The pattern of binding to gHt.st/gL did not change significantly in αVβ3 integrin-transfected 293T cells (Fig. 3, compare panels F and H).

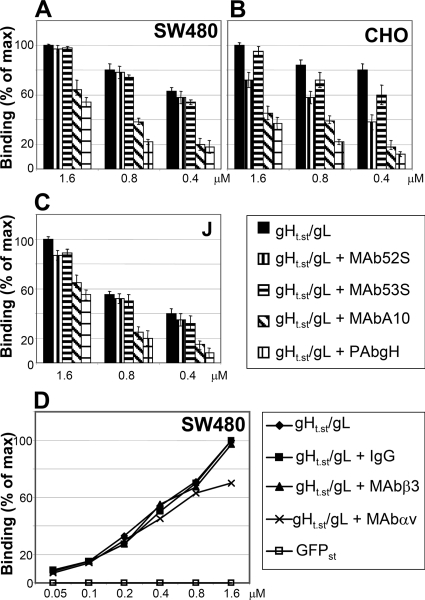

We observed some variations from batch to batch, and in some cases, saturation was not reached. To provide additional evidence that the positive CELISA results reflected authentic gHt.st/gL binding to cells and not unspecific stickiness, we measured whether antibodies to gH/gL inhibited the binding of gHt.st/gL to cells. The gHt.st/gL concentrations ranged from 0.4 to 1.6 μM, while the antibody amount was kept constant. Figure 5A to C shows that PAb to gH/gL and MAb A10 inhibited gHt.st/gL binding to SW480, CHO, and J cells, whereas MAbs 52S and 53S did not significantly inhibit binding, despite their ability to physically interact with the glycoproteins (Fig. 1C). While the different effects of the antibodies may reflect their ability to recognize specific epitopes and specific conformations of gH/gL, inhibition of binding by two antibodies argues that the CELISA results reflect authentic binding activity.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of gHt.st/gL binding to cells. (A to C) Inhibition of gHt.st/gL binding by Abs to gH/gL. gHt.st/gL at the indicated concentrations was preincubated with the indicated Abs for 1 h at room temperature and laid over the cells for 1 h of incubation at 4°C. Binding was detected as described in the legend to Fig. 4A to F. (D) Inhibition of gHt.st/gL binding to SW480 cells by Abs L230 and AP3 (7, 44) directed to αV and β3 integrins, respectively. Cells were exposed to antibodies for 1 h prior to the addition of gHt.st/gL and throughout gHt.st/gL binding. The amount of antibodies was kept constant (40 μg/ml). Mouse IgGs served as a negative control for antibodies. All details are as described in the legend to Fig. 4A to F. Each point or column represents the average of triplicate assays. Each assay was performed at least twice. Binding is expressed as a percentage of the highest value obtained for each panel. Bars denote standard deviations.

Lastly, we determined whether antibodies to αV or β3 integrin (7, 44) affected the binding of gHt.st/gL to SW480 cells. Figure 5D shows that neither antibody exerted significant inhibition.

Cumulatively, the results show that (i) gHt.st/gL was capable of binding human and rodent cells in a specific, dose-dependent manner. In many cells, binding reached saturation. Binding was specifically inhibited by some antibodies to gH/gL. (ii) gHt.st/gL also bound to β3 integrin-negative CHO cells; hence, it did not require a β3 integrin. (iii) αVβ3 integrin overexpression in 293T cells or antibodies to αV or β3 integrin did not significantly alter gHt.st/gL binding. (iv) αVβ3 integrin-negative K562 cells did not acquire the ability to bind gHt.st/gL when hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin. Points ii to iv rule out the possibility that αVβ3 integrin or any other β3 integrin serves as the cellular ligand to gHt.st/gL.

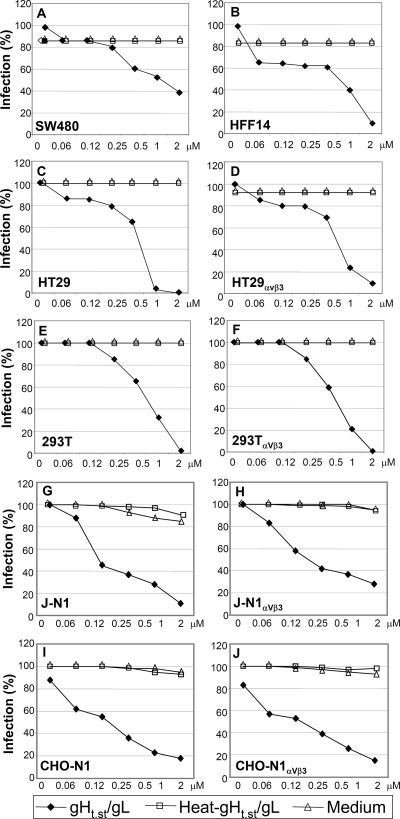

gHt.st/gL inhibits HSV infection of human cell lines.

In the next series of experiments, we asked whether gHt.st/gL blocks HSV-1 infection. The cells shown above to bind gHt.st/gL were grown in 96-well plates, preincubated with gHt.st/gL at increasing concentrations, and then infected with R8102 in the presence of the protein. The viral inoculum and gHt.st/gL were then removed, and gHt.st/gL was added to the medium. R8102 carries a lacZ reporter gene under the control of an immediate-early α27 promoter (21). The extent of β-Gal expression is a direct measurement of the extent of virus infection (21, 26). To control for specificity of gHt.st/gL inhibition, replicate cultures were exposed to heat-inactivated gHt.st/gL or to medium alone. Figure 6 shows dose-dependent inhibition of R8102 infection in all of the cell lines tested. Fifty percent inhibition was attained at about 0.5 μM, and 90% or higher inhibition was attained at 1 to 2 μM. These concentrations are similar to those required for gHt.st/gL binding (Fig. 3 and 4). Heat-inactivated gHt.st/gL failed to inhibit. Of note, the dose-response inhibition curves did not significantly vary between pairs of cells hyperexpressing or not hyperexpressing αVβ3 integrin (compare HT29 versus HT29αVβ3 cells and 293T versus 293TαVβ3 cells). K562 cells were highly resistant to HSV infection, irrespective of whether they expressed αVβ3 integrin and despite HVEM expression (Fig. 3I), and could not be used in this assay.

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of R8102 infection by gHt.st/gL. Cells were preincubated with gHt.st/gL at the indicated concentrations for 1 h. R8102 (3 PFU/cell) was added to the gHt.st/gL-containing medium for 90 min of incubation. The viral inoculum was removed, and cells were overlaid with gHt.st/gL and processed for β-Gal quantification at 8 h after infection. The negative controls consisted of incubation with heat-inactivated gHt.st/gL for 120 min at 80°C (heat-gHt.st/gL) or medium alone. A 100% infection value corresponds to infected cells not exposed to gHt.st/gL. 293T cells were either left untransfected or transfected with αV and β3 integrin plasmids (293TαVβ3). J and CHO cells were transfected either with nectin1 alone (J-N1 and CHO-N1) or with nectin1 plus αV and β3 integrin plasmids (J-N1αVβ3 and CHO-N1αVβ3). Each point represents the average of triplicate assays. Each experiment was performed at least two times. Infection is expressed as a percentage of the highest value obtained for each panel.

β3 integrin-negative CHO cells offered the opportunity to test the effect of gHt.st/gL on the infection of cells negative or positive for αVβ3 integrin. To this end, CHO cells were transfected with nectin1, with or without αV and β3 integrin, and infected with R8102 in the absence or presence of gHt.st/gL (Fig. 6I and J). HSV receptor-negative J cells were examined in parallel (Fig. 6G and H). The results show that gHt.st/gL inhibited infection in both cell lines, irrespective of αVβ3 integrin expression. Heat-inactivated gHt.st/gL did not block infection. Of note, transfection of αV and β3 integrins, in the absence of nectin1, did not render CHO or J cells susceptible to HSV (data not shown).

To further confirm that inhibition of R8102 infection was specifically exerted by gHt.st/gL and not by unspecific contaminants, we checked whether preincubation of gHt.st/gL with an antibody to gH/gL (MAb 52S) subtracted gHt.st/gL and restored R8102 infection. Because MAb 52S neutralizes infection, it could not be administered simultaneously with virus, cells, and gHt.st/gL. Hence, we immobilized MAb 52S on protein A-Sepharose; gHt.st/gL was then reacted to immobilized MAb 52S. The nonabsorbed material was assayed for inhibition of virus infection. In parallel, we immobilized an irrelevant antibody (MAb HD1 to gD) on protein A-Sepharose and subjected gHt.st/gL to the same procedure. Figure 7 shows that removal of gHt.st/gL by preincubation with MAb 52S restored R8102 infection in SW480 and HFF-14 cells. As expected, when preincubated with MAb HD1, gHt.st/gL maintained the ability to block R8102 infection.

FIG. 7.

Preincubation of gHt.st/gL with MAb 52S restores R8102 infection. Cells were infected with R8102 (details are as in the legend to Fig. 6) in the absence (No gHt.st/gL) or in the presence of gHt.st/gL (gHt.st/gL). In the “gHt.st/gL + 52S” and “gHt.st/gL + HD1” samples, gHt.st/gL was preabsorbed to MAb 52S or HD1, respectively. Preincubation of gHt.st/gL with MAb 52S, but not MAb HD1, restored R8102 infection. Each column represents the average of triplicate assays. Bars represent standard deviations.

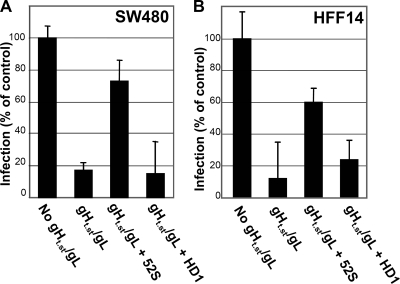

gHt.st/gL inhibits cell-cell fusion induced by transfected HSV glycoproteins.

Cells transfected with HSV gD, gB, and gH/gL undergo cell-cell fusion (58). This assay mimics the virion-to-cell fusion that occurs at virus entry. Indeed, it can be regarded as a simplified version of virion-to-cell fusion, as it only requires the essential glycoprotein quartet. 293T or COS cells were transfected with gD, gB, and gH/gL (plus luciferase in 293T cells) and exposed to gHt.st/gL (0.8 μM) from 8 h after transfection until harvesting at 48 h. The results in Fig. 8 show that gHt.st/gL reduced cell-cell fusion in both cell lines.

FIG. 8.

gHt.st/gL inhibition of cell-cell fusion in cells transiently expressing gD, gB, or gH/gL. (A) 293T cells were transfected with gD, gB, gH/gL, and T7 polymerase and seeded 24 h later at a 1:1 ratio with effector cells transfected with luciferase under the control of the T7 promoter. The mixed cell population was exposed to gHt.st/gL or GFPst (0.8 μM). The extent of cell-cell fusion was expressed as relative luciferase units (RLU). A value of 100% corresponds to cells treated with GFPst. Each column represents the average of triplicate assays. Bars represent standard deviations. (B) COS cells grown on glass coverslips were transfected with gD, gB, or gH/gL and exposed to gHt.st/gL or GFPst (0.8 μM) from 8 h after transfection until fixation at 48 h after transfection. Cells were stained by IFA with MAb H1817 to gB. The extent of fusion was expressed as the average number of nuclei present in syncytia. For each specimen, at least 100 nuclei were scored. A value of 100% corresponds to cells treated with GFPst. Bars denote standard deviations.

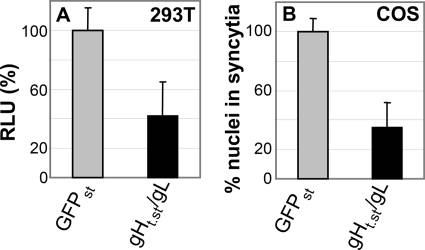

Constitutive expression of full-length gH/gL restricts HSV infection.

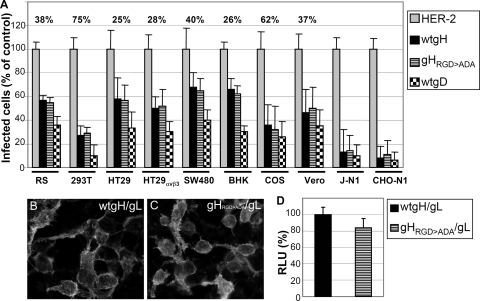

Inhibition of HSV-1 infection by soluble gHt.st/gL may be exerted through a number of mechanisms, one of which is interaction with a cell surface cognate protein and competition with virion gH/gL. To explore this possibility, we investigated whether constitutive expression of full-length gH/gL confers resistance to infection. It was reported that CHO cells transiently coexpressing nectin1 and gH/gL, but not gB, are less susceptible to infection than CHO cells expressing nectin1 alone (52). Expression of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus and human cytomegalovirus gH/gL confers resistance to virus infection (32, 50). Full-length gH/gL was transfected into 293T, HT29, HT29αVβ3, SW480, COS, Vero, RS, and BHK cells or cotransfected together with nectin1 into receptor-negative CHO and J cells. Twenty-four hours later, cells were trypsinized, seeded into 96-well trays, and infected with R8102 after a further 24 h. The extent of infection was monitored at 16 h after infection as β-Gal activity. Because different cell lines exhibit greatly varied efficiencies of transfection, for each cell line we determined the efficiency of transfection by including in the cotransfection mixture a plasmid encoding YFPVenus and determining the number of fluorescent cells over the total number of cells. The percent efficiency of transfection is given for each cell line in the first row of Fig. 9A. In all of the cell lines, gH/gL expression restricted infection. Efficiency of restriction broadly paralleled the efficiency of transfection (Fig. 9A). Full-length gD restricted infection with generally higher efficiency (Fig. 9A). The highest restriction was observed in J and CHO cells, where gH/gL was cotransfected simultaneously with nectin1; this ensured that all of the nectin1-expressing infectible cells also expressed gH/gL.

FIG. 9.

Restriction of R8102 infection by full-length gH/gL or by the gHRGD>ADA/gL and characterization of gHRGD>ADA. (A) Restriction of R8102 infection. The indicated cells were transfected with wt-gH or gHRGD>ADA (each plus gL) or with HER-2 as a negative control. As a positive control for restriction of infection, cells were transfected with wt-gD. In order to determine the number of transfected cells for each cell line, each transfection mixture included a YFPVenus plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were seeded into 96- or 24-well trays on glass coverslips and employed after a further 24 h. Cells in 96-well trays were infected with R8102 in triplicate; the number of infected cells was quantified as β-Gal activity and expressed as a percentage. A value of 100% represents cells transfected with HER-2. Each column represents the average of triplicate assays. Bars represent standard deviations. Cells on glass coverslips were employed to determine the efficiency of transfection. Specifically, for each cell line, four to eight microscopic fields were photographed and the number of YFPVenus-fluorescent cells was scored over the total number of cells. The percentage ratio of transfected over total cells represents the efficiency of transfection and is given for each cell line in the first row. J and CHO cells were transfected with nectin1 (J-N1 and CHO-N1) to render cells susceptible to R8102 infection simultaneously with gH/gL and YFPVenus. (B, C). Characterization of gHRGD>ADA. Cell surface expression of wt-gH/gL (B) or gHRGD>ADA (C). 293T cells were transfected with gHRGD>ADA or wt-gH plus gL. Cell surface expression was detected by IFA by means of MAb 53S in paraformaldehyde-fixed cells. (D) Cell-cell fusion of 293T cells transfected with gHRGD>ADA or wt-gH plus gL, gD, or gB. Cell-cell fusion was performed and quantified as described in the legend to Fig. 8. A value of 100% represents the value obtained with wt-gH. Each column represents the average of triplicate assays. Bars represent standard deviations. Panels B and C were modified by Photoshop as follows: −20% brightness, +20% contrast. RLU, relative luciferase units.

The lack of β3 integrin in CHO cells ruled out the possibility that the target of gH/gL-mediated restriction is αVβ3 integrin. Because a number of integrins, including αVβ3 integrin, recognize an RGD motif in their ligands and because gH carries an RGD motif at residues 176 to 178, we asked whether a form of gH in which the RGD motif was mutated to ADA (gHRGD>ADA) maintained the ability to restrict infection. Preliminarily, gHRGD>ADA was characterized with respect to transport to the cell surface and the ability to induce cell-cell fusion when cotransfected with gL, gD, and gB. Figure 9C and D shows that gHRGD>ADA was expressed at the cell surface and was capable of inducing syncytia. Thus, the RGD-to-ADA substitutions did not alter the major biological activities of gH/gL.

The same cells tested above for wt-gH/gL-mediated restriction of infection were transiently transfected with gHRGD>ADA/gL. Figure 9A shows that gHRGD>ADA/gL was as effective as wt-gH/gL at restricting infection. We conclude that constitutive expression of gH/gL restricts infection and that the gH/gL-mediated restriction of infection is not altered in a gH mutant in which the RDG motif is abolished.

DISCUSSION

Production of soluble forms of the glycoproteins involved in the entry of HSV, and herpesviruses in general, has been instrumental in defining their role, in particular, their capacity to interact with cognate cellular proteins. Of the four glycoproteins required for HSV entry into cells, the heterodimer gH/gL has been the more refractory to production in soluble form in quantities suitable for biological characterization. This has been true also for gH/gL of other herpesviruses, with the possible exception of EBV gH/gL (12, 38). We report that gHt.st/gL produced in insect cells under the control of an inducible promoter (i) maintained reactivity to conformation-dependent MAbs 52S, 53S, and A10, implying that it adopts a biologically relevant conformation, (ii) bound the surface of a variety of cells, including cells negative for β3 integrin, and (iii) inhibited HSV infection. In addition, constitutive expression of full-length gH/gL rendered cells resistant to HSV infection.

gH/gL interacts with a cell surface cognate protein(s) at virus entry and fusion.

Three lines of evidence support the conclusion that gH/gL interacts with a cell surface cognate protein(s) at virus entry and fusion. First, gHt.st/gL bound a number of cell lines of human or rodent origin in a dose-dependent manner. Binding occurred at concentrations similar to those required for the binding of soluble gB and of soluble gD to the same cells (here and reference 8). Second, the most relevant property of gHt.st/gL was its ability to block HSV infection. Dose-dependent inhibition was observed with all of the cell lines tested (all capable of binding soluble gHt.st/gL). Binding and inhibition of infection occurred at similar gHt.st/gL concentrations. Inasmuch as gHt.st/gL also inhibited cell-cell fusion in cells transiently expressing gD, gH/gL, and gB, entry/fusion is the most likely step blocked by gHt.st/gL. Third, in principle, gHt.st/gL may block virus entry by two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms. In one case, the target is the virion gH/gL, and gHt.st/gL interferes with virion gH/gL oligomerization or refolding and prevents gH/gL from adopting a fusion-active conformation or from interacting with cellular membranes. In the second case, the target is a cognate cell surface protein with which gH/gL putatively interacts. Addition of gHt.st/gL to cells competes for the binding of virion gH/gL to the cognate cellular protein. To provide evidence for the second mechanism, we expressed full-length gH/gL in a variety of susceptible cells. A large body of evidence obtained in earlier studies with gD (15, 37) and other viral glycoproteins, including HIV gp120 (40), indicates that constitutive expression of a receptor-binding glycoprotein results in restriction of infection. Preliminary evidence that HSV gH/gL may restrict infection came from the finding that expression of gH/gL in receptor-negative CHO cells decreases the efficiency of infection, provided that nectin1 was cotransfected to render cells susceptible (52). Further yet, expression of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus and human cytomegalovirus gH/gL inhibits infection (32, 50). Here, constitutive expression of gH/gL resulted in reduced infection of all of the cell lines tested. The extent of the reduction broadly paralleled the efficiency of gH/gL transfection. It was highest (∼90%) in CHO and J cells, where gH/gL and nectin1 were cotransfected, and therefore all of the nectin1-transfected susceptible cells also expressed gH/gL.

Cumulatively, the present results provide several indirect lines of evidence that HSV gH/gL interacts with a cell surface cognate protein(s) and that this interaction is critical to the process of entry/fusion.

The gH/gL-interacting cell surface protein is not necessarily αVβ3 integrin.

A number of indications point to integrins as players in infection with herpesviruses, in particular human cytomegalovirus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, EBV, and equine herpesvirus (1, 18, 59, 61). With respect to HSV, gHt/gL immobilized on plastic facilitated the adhesion of CHO cells hyperexpressing a number of integrins, in particular αVβ3 integrin, but not that of β3 integrin-negative wt-CHO cells (47). This property may result from a direct interaction of gH/gL with αVβ3 integrin or indirectly from the ability of certain integrins to uncover and make accessible unidentified cellular proteins and enable their interaction with gH/gL. It was therefore of interest to investigate whether gH/gL is a ligand to αVβ3 integrin or to αV and β3 integrins in general. We observed that gHt.st/gL failed to bind K562 cells, irrespective of whether they were negative or positive for αVβ3 integrin (cell surface exposure of the integrin was assessed by reactivity to appropriate antibodies). Conversely, gHt.st/gL bound β3 integrin-negative CHO cells. Furthermore, binding of gHt.st/gL to 239T and HT29 cells was little modified by overexpression of αVβ3 integrin. Lastly, constitutive expression of wt-gH/gL or of RGD mutant gHRGD>ADA/gL impaired infection in an indistinguishable manner.

With respect to integrins, the major conclusions of this study were threefold. (i) The presence of β3 integrins was not a requirement for gHt.st/gL binding to cells (CHO) and inhibition of virus infection. Conversely, the transgenic expression of αV and β3 integrins in cells negative for both subunits (K562) did not confer the ability to bind gHt.st/gL. A function-blocking αV integrin subunit MAb failed to reduce gHt.st/gL binding to integrin-positive cells. Assuming that the binding of gHt.st/gL to cell surfaces and inhibition of infection are accomplished through interaction with the same cell surface protein(s), the results rule out the possibility that the cognate cellular protein for gH/gL is αVβ3 integrin. (ii) Even though αVβ3 integrin is not required for soluble gH/gL to bind to cells and/or to inhibit virus infection, the results do not rule out the possibilities that HSV gH/gL promiscuously interacts with a spectrum of integrins and that, in the absence of specific integrins (e.g., any αV or β3 integrin heterodimer), it still interacts with other members of the family. Promiscuous usage of integrins by herpesviruses was previously described (18, 60). Analysis of the entire spectrum of integrins possibly involved in HSV entry and postentry steps requires the availability and generation of a high number of specific reagents and was beyond the scope of this study. (iii) The results do not rule out the possibility that, in specific cells, integrins play some roles in HSV entry or postentry steps, particularly in signaling cascades. Indeed, we have evidence that αVβ3 integrin may participate in HSV postentry steps (T. Gianni and G. Campadelli-Fiume, unpublished data). Of note, K562 cells may prove an interesting cell line in the search for a candidate gH/gL cognate protein(s), as they were resistant to HSV infection independently of whether they hyperexpressed αV and β3 integrins and despite the fact that they expressed HVEM. Taking into account the fact that the cognate cellular protein to gH/gL is not αVβ3 integrin, these observations raise the possibility that K562 cell resistance to infection is a consequence of the lack of a cellular partner of gH/gL.

How many cell surface proteins interact with HSV envelope glycoproteins to enable infection?

A question raised by this and recent studies (9, 51, 57) is how many cell surface proteins interact with HSV envelope glycoproteins in order to promote virus entry. Apart from the rather unspecific polymer heparan sulfate, which enables the initial attachment of virions to cells, HSV receptors appear to cluster into two groups. One includes the gD receptors responsible for virus tropism and for triggering of fusion (20, 21, 25, 41). The second group includes cellular proteins interacting with gB, for which there is direct and indirect evidence (9, 51, 57), and possibly the gH/gL-interacting protein(s) investigated here. Based on the sequential order of glycoproteins' involvement, it is tempting to propose that the cell surface proteins in the second group do not serve as tropism receptors; rather, they may fulfill a number of different functions, such as activation of endocytosis, activation of gB and gH/gL such that they become fusion competent, induction of signaling activities that target virus internalization, modification of the cellular cytoskeleton, etc. A similar distinction might apply in part also to other herpesviruses and was elegantly reviewed recently (13). Thus, the EBV gp42-interacting human leukocyte antigen (62), the proteins interacting with HCMV U128-131 (33), and CD46 interacting with human herpesvirus 6 gO, gQ1, and gQ2 (42) are likely to represent tropism receptors. The integrins that interact with human cytomegalovirus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, and EBV gH/gL possibly belong to the second group (1, 18, 61). The functional characterization of the ever-growing number of receptors will prove whether this subdivision is correct and to what extent cellular receptors for herpesviruses other than HSV diverge from this model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roselyn Eisenberg and Gary Cohen (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) for the gift of soluble gB and gD and antibodies.

This work was supported by a TargetHerpes EU grant (LSHG-CT-2006-037517), by Fondi Roberto and Cornelia Pallotti from our department, and by a University of Bologna Ricerca Fondamentale Orientata grant. We thank IBA GmbH (Göttingen) and PRIMM (Milan), partners in the TargetHerpes Project, for performing purification of gHt.st/gL and generation of gH/gL MAbs at their facilities.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akula, S. M., N. P. Pramod, F. Z. Wang, and B. Chandran. 2002. Integrin alpha3beta1 (CD 49c/29) is a cellular receptor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) entry into the target cells. Cell 108:407-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atanasiu, D., J. C. Whitbeck, T. M. Cairns, B. Reilly, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2007. Bimolecular complementation reveals that glycoproteins gB and gH/gL of herpes simplex virus interact with each other during cell fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:18718-18723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avitabile, E., C. Forghieri, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2007. Complexes between herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gD, gB, and gH detected in cells by complementation of split enhanced green fluorescent protein. J. Virol. 81:11532-11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avitabile, E., C. Forghieri, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2009. Cross talk among the glycoproteins involved in herpes simplex virus entry and fusion: the interaction between gB and gH/gL does not necessarily require gD. J. Virol. 83:10752-10760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avitabile, E., G. Lombardi, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2003. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein K, but not its syncytial allele, inhibits cell-cell fusion mediated by the four fusogenic glycoproteins, gD, gB, gH,and gL. J. Virol. 77:6836-6844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backovic, M., and T. S. Jardetzky. 2009. Class III viral membrane fusion proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19:189-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazzoni, G., D. T. Shih, C. A. Buck, and M. E. Hemler. 1995. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel beta 1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25570-25577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bender, F. C., M. Samanta, E. E. Heldwein, M. Ponce de Leon, E. Bilman, H. Lou, J. C. Whitbeck, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2007. Antigenic and mutational analyses of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B reveal four functional regions. J. Virol. 81:3827-3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender, F. C., J. C. Whitbeck, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2005. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B binds to cell surfaces independently of heparan sulfate and blocks virus entry. J. Virol. 79:11588-11597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bender, F. C., J. C. Whitbeck, M. Ponce de Leon, H. Lou, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2003. Specific association of glycoprotein B with lipid rafts during herpes simplex virus entry. J. Virol. 77:9542-9552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blystone, S. D., I. L. Graham, F. P. Lindberg, and E. J. Brown. 1994. Integrin alpha v beta 3 differentially regulates adhesive and phagocytic functions of the fibronectin receptor alpha 5 beta 1. J. Cell Biol. 127:1129-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borza, C. M., A. J. Morgan, S. M. Turk, and L. M. Hutt-Fletcher. 2004. Use of gHgL for attachment of Epstein-Barr virus to epithelial cells compromises infection. J. Virol. 78:5007-5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burckhardt, C. J., and U. F. Greber. 2009. Virus movements on the plasma membrane support infection and transmission between cells. PloS Pathog. 5:e1000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campadelli-Fiume, G., M. Amasio, E. Avitabile, A. Cerretani, C. Forghieri, T. Gianni, and L. Menotti. 2007. The multipartite system that mediates entry of herpes simplex virus into the cell. Rev. Med. Virol. 17:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campadelli-Fiume, G., M. Arsenakis, F. Farabegoli, and B. Roizman. 1988. Entry of herpes simplex virus 1 in BJ cells that constitutively express viral glycoprotein D is by endocytosis and results in degradation of the virus. J. Virol. 62:159-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carfí, A., S. H. Willis, J. C. Whitbeck, C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and D. C. Wiley. 2001. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bound to the human receptor HveA. Mol. Cell 8:169-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheresh, D. A., and R. C. Spiro. 1987. Biosynthetic and functional properties of an Arg-Gly-Asp-directed receptor involved in human melanoma cell attachment to vitronectin, fibrinogen, and von Willebrand factor. J. Biol. Chem. 262:17703-17711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesnokova, L. S., S. L. Nishimura, and L. M. Hutt-Fletcher. 2009. Fusion of epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus proteins is triggered by binding of viral glycoproteins gHgL to integrins {alpha}v{beta}6 or {alpha}v{beta}8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:20464-20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cocchi, F., D. Fusco, L. Menotti, T. Gianni, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2004. The soluble ectodomain of herpes simplex virus gD contains a membrane-proximal pro-fusion domain and suffices to mediate virus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:7445-7450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cocchi, F., L. Menotti, V. Di Ninni, M. Lopez, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2004. The herpes simplex virus JMP mutant enters receptor-negative J cells through a novel pathway independent of the known receptors nectin1, HveA, and nectin2. J. Virol. 78:4720-4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cocchi, F., L. Menotti, P. Mirandola, M. Lopez, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 1998. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 in human cells. J. Virol. 72:9992-10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fusco, D., C. Forghieri, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2005. The pro-fusion domain of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D (gD) interacts with the gD N terminus and is displaced by soluble forms of viral receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9323-9328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gahmberg, C. G., S. C. Fagerholm, S. M. Nurmi, T. Chavakis, S. Marchesan, and M. Gronholm. 2009. Regulation of integrin activity and signalling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790:431-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galdiero, S., A. Falanga, M. Vitiello, H. Browne, C. Pedone, and M. Galdiero. 2005. Fusogenic domains in herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J. Biol. Chem. 280:28632-28643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geraghty, R. J., A. Fridberg, C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 2001. Use of chimeric nectin-1(HveC)-related receptors to demonstrate that ability to bind alphaherpesvirus gD is not necessarily sufficient for viral entry. Virology 285:366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geraghty, R. J., C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1998. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science 280:1618-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianni, T., M. Amasio, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2009. Herpes simplex virus gD forms distinct complexes with fusion executors gB and gH/gL through the C-terminal profusion. J. Biol. Chem. 284:17370-17382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gianni, T., R. Fato, C. Bergamini, G. Lenaz, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2006. Hydrophobic alpha-helices 1 and 2 of herpes simplex virus gH interact with lipids, and their mimetic peptides enhance virus infection and fusion. J. Virol. 80:8190-8198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gianni, T., P. L. Martelli, R. Casadio, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2005. The ectodomain of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein H contains a membrane alpha-helix with attributes of an internal fusion peptide, positionally conserved in the Herpesviridae family. J. Virol. 79:2931-2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gianni, T., L. Menotti, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2005. A heptad repeat in herpes simplex virus gH, located downstream of the alpha-helix with attributes of a fusion peptide, is critical for virus entry and fusion. J. Virol. 79:7042-7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruenheid, S., L. Gatzke, H. Meadows, and F. Tufaro. 1993. Herpes simplex virus infection and propagation in a mouse L cell mutant lacking heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Virol. 67:93-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hahn, A., A. Birkmann, E. Wies, D. Dorer, K. Mahr, M. Sturzl, F. Titgemeyer, and F. Neipel. 2009. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gH/gL: glycoprotein export and interaction with cellular receptors. J. Virol. 83:396-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hahn, G., M. G. Revello, M. Patrone, E. Percivalle, G. Campanini, A. Sarasini, M. Wagner, A. Gallina, G. Milanesi, U. Koszinowski, F. Baldanti, and G. Gerna. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J. Virol. 78:10023-10033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heldwein, E. E., H. Lou, F. C. Bender, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and S. C. Harrison. 2006. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science 313:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutchinson, L., H. Browne, V. Wargent, N. Davis-Poynter, S. Primorac, K. Goldsmith, A. C. Minson, and D. C. Johnson. 1992. A novel herpes simplex virus glycoprotein, gL, forms a complex with glycoprotein H (gH) and affects normal folding and surface expression of gH. J. Virol. 66:2240-2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson, D. C., R. L. Burke, and T. Gregory. 1990. Soluble forms of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bind to a limited number of cell surface receptors and inhibit virus entry into cells. J. Virol. 64:2569-2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson, R. M., and P. G. Spear. 1989. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D mediates interference with herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 63:819-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirschner, A. N., A. S. Lowrey, R. Longnecker, and T. S. Jardetzky. 2007. Binding-site interactions between Epstein-Barr virus fusion proteins gp42 and gH/gL reveal a peptide that inhibits both epithelial and B-cell membrane fusion. J. Virol. 81:9216-9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krummenacher, C., V. M. Supekar, J. C. Whitbeck, E. Lazear, S. A. Connolly, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, D. C. Wiley, and A. Carfí 2005. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry. EMBO J. 24:4144-4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landau, N. R., M. Warton, and D. R. Littman. 1988. The envelope glycoprotein of the human immunodeficiency virus binds to the immunoglobulin-like domain of CD4. Nature 334:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montgomery, R. I., M. S. Warner, B. J. Lum, and P. G. Spear. 1996. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell 87:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori, Y. 2009. Recent topics related to human herpesvirus 6 cell tropism. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1001-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagai, T., K. Ibata, E. S. Park, M. Kubota, K. Mikoshiba, and A. Miyawaki. 2002. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman, P. J., R. W. Allen, R. A. Kahn, and T. J. Kunicki. 1985. Quantitation of membrane glycoprotein IIIa on intact human platelets using the monoclonal antibody, AP-3. Blood 65:227-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicola, A. V., A. M. McEvoy, and S. E. Straus. 2003. Roles for endocytosis and low pH in herpes simplex virus entry into HeLa and Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Virol. 77:5324-5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicola, A. V., C. Peng, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1997. Antigenic structure of soluble herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D correlates with inhibition of HSV infection. J. Virol. 71:2940-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parry, C., S. Bell, T. Minson, and H. Browne. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H binds to alphavbeta3 integrins. J. Gen. Virol. 86:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pertel, P. E., A. Fridberg, M. L. Parish, and P. G. Spear. 2001. Cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gB, gD, and gH-gL requires a gD receptor but not necessarily heparan sulfate. Virology 279:313-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rovero, S., A. Amici, E. D. Carlo, R. Bei, P. Nanni, E. Quaglino, P. Porcedda, K. Boggio, A. Smorlesi, P. L. Lollini, L. Landuzzi, M. P. Colombo, M. Giovarelli, P. Musiani, and G. Forni. 2000. DNA vaccination against rat her-2/Neu p185 more effectively inhibits carcinogenesis than transplantable carcinomas in transgenic BALB/c mice. J. Immunol. 165:5133-5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryckman, B. J., M. C. Chase, and D. C. Johnson. 2008. HCMV gH/gL/UL128-131 interferes with virus entry into epithelial cells: evidence for cell type-specific receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14118-14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satoh, T., J. Arii, T. Suenaga, J. Wang, A. Kogure, J. Uehori, N. Arase, I. Shiratori, S. Tanaka, Y. Kawaguchi, P. G. Spear, L. L. Lanier, and H. Arase. 2008. PILRalpha is a herpes simplex virus-1 entry coreceptor that associates with glycoprotein B. Cell 132:935-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scanlan, P. M., V. Tiwari, S. Bommireddy, and D. Shukla. 2003. Cellular expression of gH confers resistance to herpes simplex virus type-1 entry. Virology 312:14-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Showalter, S. D., M. Zweig, and B. Hampar. 1981. Monoclonal antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 1 proteins, including the immediate-early protein ICP 4. Infect. Immun. 34:684-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shukla, D., J. Liu, P. Blaiklock, N. W. Shworak, X. Bai, J. D. Esko, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, R. D. Rosenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stefan, A., M. De Lillo, G. Frascaroli, P. Secchiero, F. Neipel, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 1999. Development of recombinant diagnostic reagents based on pp85(U14) and p86(U11) proteins to detect the human immune response to human herpesvirus 7 infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3980-3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Subramanian, R. P., and R. J. Geraghty. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 mediates fusion through a hemifusion intermediate by sequential activity of glycoproteins D, H, L, and B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2903-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suenaga, T., T. Satoh, P. Somboonthum, Y. Kawaguchi, Y. Mori, and H. Arase. 2010. Myelin-associated glycoprotein mediates membrane fusion and entry of neurotropic herpesviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:866-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turner, A., B. Bruun, T. Minson, and H. Browne. 1998. Glycoproteins gB, gD, and gHgL of herpes simplex virus type 1 are necessary and sufficient to mediate membrane fusion in a Cos cell transfection system. J. Virol. 72:873-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van de Walle, G. R., S. T. Peters, B. C. VanderVen, D. J. O'Callaghan, and N. Osterrieder. 2008. Equine herpesvirus 1 entry via endocytosis is facilitated by alphaV integrins and an RSD motif in glycoprotein D. J. Virol. 82:11859-11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veettil, M. V., S. Sadagopan, N. Sharma-Walia, F. Z. Wang, H. Raghu, L. Varga, and B. Chandran. 2008. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus forms a multimolecular complex of integrins (alphaVbeta5, alphaVbeta3, and alpha3beta1) and CD98-xCT during infection of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, and CD98-xCT is essential for the postentry stage of infection. J. Virol. 82:12126-12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, D., and T. Shenk. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:18153-18158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, X., W. J. Kenyon, Q. Li, J. Mullberg, and L. M. Hutt-Fletcher. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus uses different complexes of glycoproteins gH and gL to infect B lymphocytes and epithelial cells. J. Virol. 72:5552-5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]