Abstract

Candida species are a common source of nosocomial bloodstream infections in critically ill patients. The sensitivity of the traditional diagnostic procedure based on blood culture is variable, and it usually takes 2 to 4 days before growth of Candida species is detected. We developed a 4-h method for the quantification of Candida species in blood, combining immunomagnetic separation (IMS) with solid-phase cytometry (SPC) using viability labeling. Additionally, Candida albicans cells could be identified in real time by using fluorescent in situ hybridization. By analysis of spiked blood samples, our method was shown to be sensitive and specific, with a low detection limit (1 cell/ml of blood). In a proof-of-concept study, we applied the IMS/SPC method to 16 clinical samples and compared it to traditional blood culture. Our method proved more sensitive than culture (seven samples were positive with IMS/SPC but negative with blood culture), and identification results were in agreement. The IMS/SPC data also suggest that mixed infections might occur frequently, as C. albicans and at least one other Candida species were found in five samples. Additionally, in two cases, high numbers of cells (175 to 480 cells/ml of blood) were associated with an endovascular source of infection.

Candida species are a common source of nosocomial bloodstream infections in critically ill patients, with mortality rates exceeding 40%. Rapid detection and identification of Candida albicans and other Candida species could result in early initiation of adequate antifungal therapy, an important factor in reducing morbidity and mortality (3, 16).

At present, the gold standard for the detection of Candida species in the bloodstream is culture of blood samples. Although blood culture systems have evolved in recent years from manual to fully automated systems, the diagnostic sensitivity is still variable and differs greatly among studies, with 40 to 82% of blood culture bottles spiked with Candida or from patients with proven candidemia showing positive results (4, 6, 9, 10, 18). Possible explanations are the small numbers of Candida cells present in the blood during fungemia (10 to 25 cells per 10 ml of blood) (4, 10, 18), the use of growth media which are not optimal for fungal growth, and the presence of antimycotics in the blood (6). Additionally, it usually takes 2 to 4 days before growth of Candida species is detected in blood culture bottles (4, 10).

Several studies have shown good results by using PCR on DNA isolated from whole blood for the detection of candidemia (5, 13, 21, 22). However, one of the problems with PCR is the possibility of detecting DNA from dead and/or degrading yeast cells instead of living yeasts, leading to false-positive results (5, 13, 21, 22). Also, in many cases, only small sample volumes can be used, or a long and cumbersome sample preparation is needed to reduce the influence of inhibitors present in blood (5, 13).

Another approach is to recover yeast cells by immunomagnetic separation (IMS) prior to further analysis. Magnetic beads coated with antibodies are used to capture the yeast cells present in the clinical sample, and separation occurs in a magnetic field (15). Although IMS has been used frequently for the recovery of specific microorganisms from different samples, the recovery rate is rather low (8, 15, 17). After separation of the cells from the sample, several analysis methods, such as plating, PCR, and solid-phase cytometry (SPC), can be used to quantify the number of microorganisms.

In SPC, the principles of epifluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry are combined. Microorganisms are retained on a membrane filter, fluorescently labeled, and automatically counted by a Chemscan RDI laser scanning device. Subsequently, the data for each fluorescent spot are analyzed by a computer to differentiate between fluorescent microorganisms and particles. Each retained spot can be inspected visually by an epifluorescence microscope (11, 20). Due to its low detection limit, speed, and possible use of taxonomic probes for identification, SPC has the potential to overcome the shortcomings of other methods for quantification of Candida species in blood samples (7, 14).

In the present study, a method for the rapid quantification of Candida species and identification of C. albicans in whole blood, based on IMS and SPC, is described. This method was optimized using spiked blood samples and subsequently used to analyze 16 blood samples from high-risk patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IMS/SPC method.

Thirty microliters of polyclonal anti-C. albicans antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Acris Antibodies, Herford, Germany) and 30 μl monoclonal anti-FITC antibody bound to microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were added to an EDTA-treated whole-blood sample (maximum volume, 15 ml). After incubation at room temperature for 1 h with head-to-tail rotation, the sample was loaded on a whole-blood column (Miltenyi Biotec). Prior to loading, the column was inserted into a QuadroMACS cell separator (Miltenyi Biotec) and prewashed with 3 ml of separation buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.2). Afterwards, the column was washed three times with 3 ml of separation buffer and removed from the magnetic field, and the yeasts were eluted with 5 ml of elution buffer (Miltenyi Biotec).

The eluate was filtered over a 2.0-μm Cycloblack-coated polyester membrane filter (AES-Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France), and filters were incubated at 55°C for 30 min with 100 μl of PNAFlow reagent (AdvanDx, Vedbaek, Denmark) containing a FITC-conjugated peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe specific for Candida albicans (19). Subsequently, filters were incubated with 100 μl Wash BufferFlow (AdvanDx) for 10 min at 55°C. Finally, tyramide signal amplification was used to obtain red fluorescent C. albicans cells. To this end, the filter was placed on top of 100 μl polyclonal anti-FITC antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (AbD Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) (10 μg/ml PBS) for 30 min at 30°C. A tyramide Alexa Fluor derivative (Invitrogen, Leek, Netherlands) was then converted to its red fluorescent form by incubating the filter on 100 μl tyramide solution (stock solution diluted 1:50 in amplification buffer) for 30 min at 30°C. Between different steps, filters were rinsed three times with 1 ml PBS. Finally, all viable microorganisms were fluorescently labeled (green) by incubating the filters at 37°C for 1 h on a cellulose pad saturated with 600 μl ChemChrome V6 viability staining solution (stock solution diluted 1:100 in the labeling buffer ChemSol B2; AES-Chemunex). With this procedure, all fungal cells retained on the filter are labeled green.

The filters with labeled microorganisms were placed on a holder, on top of a support pad (AES-Chemunex) moistened with 100 μl of ChemSol B2 (AES-Chemunex), and scanned by a ChemScan RDI cytometer (AES-Chemunex). This solid-phase cytometer consists of an argon laser emitting light at 488 nm and two photomultiplier tubes to detect the fluorescent light emitted by the labeled cells. The produced signals are processed by a personal computer (PC), applying a series of software discriminants to differentiate valid signals associated with labeled Candida cells from other fluorescent particles. Subsequently, results are displayed as green spots on a membrane filter image in a primary scan map and, after software elimination of background, a secondary scan map (14). To confirm the results, visual inspection using an Olympus BX40 epifluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was performed. The filter holder was placed on a computer-driven moving stage in exactly the same position as in the Chemscan RDI machine. Subsequent highlighting of a green spot in the secondary scan map on the PC resulted in the direction of the microscope to the respective position on the membrane filter (2, 12), which allowed rapid visual inspection of all fluorescent spots. The red fluorescence of C. albicans cells can easily be observed using a 590-nm-cutoff emission filter (20).

Preparation of spiking solutions.

In order to validate the IMS/SPC procedure, several experiments with spiked blood samples were carried out. An overview of the fungi used in these experiments is given in Table 1. These fungi were cultured overnight at 30°C in Sabouraud liquid medium, and serial dilutions were made in physiological saline. Subsequently, the number of cells was determined by SPC prior to spiking (20), and 1 ml of the obtained cell suspensions was used to spike the blood samples. For all spiking experiments, blood was freshly drawn from healthy volunteers, maintained at 4°C, and used in experiments the same day.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the fungi used for sensitivity and specificity testing and their reactivities with the capture antibody and the PNA probe used in the assay

| Species | Strain designationa | Reactivity with antibody used for immunomagnetic capture | Reactivity with PNA probe used for identification of C. albicans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | ATCC MYA-682 | + | + |

| ATCC MYA-2876 | + | + | |

| ATCC 10231 | + | + | |

| IHEM 9559 | + | + | |

| IHEM 10284 | + | + | |

| MUCL 29903 | + | + | |

| MUCL 29800 | + | + | |

| MUCL 29919 | + | + | |

| MUCL 29981 | + | + | |

| MUCL 30112 | + | + | |

| NCYC 1467 | + | + | |

| Candida dubliniensis | IHEM 14280 | + | − |

| Candida famata | CI | + | − |

| Candida glabrata | MUCL 15664 | + | − |

| MUCL 29833 | + | − | |

| Candida guilliermondii | CI | + | − |

| Candida inconspicua | CI | + | − |

| Candida kefyr | CI | + | − |

| Candida krusei | IHEM 1796 | + | − |

| Candida lusitaniae | CI | + | − |

| Candida maris | CI | + | − |

| Candida parapsilosis | IHEM 3270 | + | − |

| Candida pseudotropicalis | CI | + | − |

| Candida tropicalis | IHEM 4222 | + | − |

| IHEM 4225 | + | − | |

| MUCL 29952 | + | − | |

| MUCL 30002 | + | − | |

| Aspergillus flavus | IHEM 2700 | − | − |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | IHEM 3768 | − | − |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | IHEM 14513 | − | − |

| Fusarium graminearum | IHEM 2994 | − | − |

| Fusarium oxysporum | IHEM 14513 | − | − |

| Fusarium solani | IHEM 6743 | − | − |

| Penicillium chrysogenum | IHEM 3035 | − | − |

| Penicillium simplicissimum | IHEM 1202 | − | − |

| Pseudallescheria boydii | CBS 101.22 | − | − |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ATCC 9763 | − | − |

| Scedosporium prolificans | CBS 467.74 | − | − |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Netherlands); CI, clinical isolate from our own collection; IHEM, Instituut voor Hygiene en Epidemiologie (Belgium); MUCL, Mycothèque de l'Université Catholique de Louvain (Belgium); NCYC, National Collection of Yeast Cultures (United Kingdom).

Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of the assay.

For sensitivity testing, the recovery of all Candida species (27 strains) was determined by analysis of spiked blood samples (10 to 50 Candida cells/10 ml of blood) with IMS/SPC. The specificity of the antibody for immunomagnetic capture of Candida cells was tested by spiking blood with various fungi not belonging to the genus Candida (11 strains). Additionally, the specificity of the PNA probe for identification of C. albicans was examined using all other Candida strains (16 strains) (Table 1).

Determination of detection limit.

In order to determine the detection limit of the IMS/SPC assay, a suspension of C. albicans ATCC MYA-2876 (76 cells/ml, as determined by SPC) was serially diluted (six times), and the numbers of cells present in the dilutions were also determined by SPC. Subsequently, blood samples from healthy volunteers were spiked with 1 ml of these solutions, and recovery with the IMS/SPC procedure was determined.

Comparison of IMS/SPC with blood culture, using spiked blood.

In order to compare the IMS/SPC method with conventional blood culture, five whole-blood samples (10 ml) were obtained from 10 healthy volunteers. One unspiked sample per healthy volunteer was used as a negative control and was analyzed with the IMS/SPC assay simultaneously with the other samples. Two samples per volunteer were spiked with C. albicans ATCC MYA-2876, and the other two were spiked with C. dubliniensis IHEM 14280, C. glabrata MUCL 29833, C. krusei IHEM 1795, C. parapsilosis IHEM 3270, or C. tropicalis MUCL 29952. The whole-blood samples were spiked with 1 to 100 Candida cells. Two spiked whole-blood samples were analyzed immediately by IMS/SPC, and two were analyzed by conventional blood culture. To that end, the last two spiked blood samples were aseptically introduced into a BacT/Alert FA blood culture bottle (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), and the bottle was incubated at 37°C. The change of color of the indicator was monitored visually.

Storage of blood samples.

In order to investigate if storage of the blood samples at 4°C has an influence on the viability of Candida cells, analysis was performed immediately and 3, 6, 9, 16, and 24 h after spiking. To that end, two times six blood samples (5 ml) from a healthy volunteer were spiked with 24 or 76 C. albicans ATCC MYA-2876 cells (cell number determined by SPC) and stored at 4°C until analysis.

Proof of concept by analysis of clinical samples.

Finally, 16 samples from 15 patients with candidemia or suspected candidemia were analyzed (Table 2). This research was approved by the ethical committee of University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium) (study number S51459). Blood samples were stored at 4°C until analysis, and all samples were analyzed within 24 h of collection (Table 2). An equal aliquot of the blood sample was analyzed both by the IMS/SPC procedure and by using a BacT/Alert FA blood culture bottle that was monitored visually. If the blood culture was positive, a subculture on Chromagar (BD) was made, and subsequent identification of all yeasts recovered was performed using an API-20C AUX system (bioMérieux).

TABLE 2.

Overview of characteristics of clinical samples included in the study and the results obtained after analysis with traditional blood culture and with IMS/SPC method

| Patient | Blood culture result obtained before inclusion in studya | Sample collection date (mo-day-yr) | Analysis date (mo-day-yr) | Treatment prior to sample collectionb | Results of analysis of clinical samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood culture | No. of cells/ml of blood (IMS/SPC) |

||||||

| C. albicans | Other Candida spp. | ||||||

| A | − | 06-16-09 | 06-16-09 | − | Negative | 3 | 3 |

| B | C. glabrata | 08-10-09 | 08-11-09 | Fluconazole | Negative | 0 | 2 |

| C | C. tropicalis | 08-11-09 | 08-12-09 | Fluconazole | C. tropicalis | 0 | >175c |

| − | 08-20-09 | 08-20-09 | Fluconazole and anidulafungin | Negative | 0 | 2 | |

| D | C. albicans | 08-20-09 | 08-20-09 | Fluconazole | Negative | 3 | 0 |

| E | C. glabrata | 08-20-09 | 08-21-09 | − | C. glabrata | 3 | 4 |

| F | C. glabrata | 08-20-09 | 08-21-09 | Fluconazole and caspofungin | C. glabrata | 0 | 480 |

| G | C. albicans | 09-14-09 | 09-15-09 | Fluconazole | Negative | 0 | 0 |

| H | C. tropicalis | 09-14-09 | 09-15-09 | Fluconazole | Negative | 0 | 0 |

| I | C. albicans, C. glabrata | 09-14-09 | 09-15-09 | Fluconazole | C. albicans | 2 | 0 |

| J | C. glabrata | 10-06-09 | 10-07-09 | − | C. glabrata | 0 | 4 |

| K | C. glabrata | 10-07-09 | 10-08-09 | − | Negative | 6 | 3 |

| L | − | 10-07-09 | 10-08-09 | − | Negative | 0 | 0 |

| M | C. parapsilosis | 10-08-09 | 10-09-09 | Fluconazole | Negative | 1 | 6 |

| N | C. albicans | 12-04-09 | 12-05-09 | Fluconazole | C. albicans | 1 | 1 |

| O | C. krusei | 01-04-10 | 01-05-10 | Caspofungin | Negative | ||

−, no positive blood culture was obtained prior to inclusion in this study.

−, patients did not receive treatment prior to inclusion in this study.

For this blood sample, 4 ml was filtered and more than 700 Candida cells were present on the filter, but a reliable quantification was impossible. Filtration of a smaller volume could have led to a more reliable quantification.

RESULTS

Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of the assay.

The sensitivity of the assay was confirmed, as the average recovery (± standard deviation) for all Candida strains tested was 114% (±20%) (n = 27) after IMS/SPC analysis. The method proved highly specific, and only cells belonging to Candida species were retained using the IMS procedure (Table 1). The specificity of the PNA probe was confirmed, as only C. albicans cells yielded red fluorescence (Table 1).

Determination of detection limit.

A linear correlation between the numbers of cells (ranging from 0 to 76, as determined with SPC prior to spiking) in the spiking solutions and the numbers of cells found in the blood samples supplemented with this solution was obtained (data not shown). The average recovery (± standard deviation) was 116% (±18%), and the detection limit was one cell per 10 ml of blood.

Comparison of IMS/SPC with blood culture, using spiked blood.

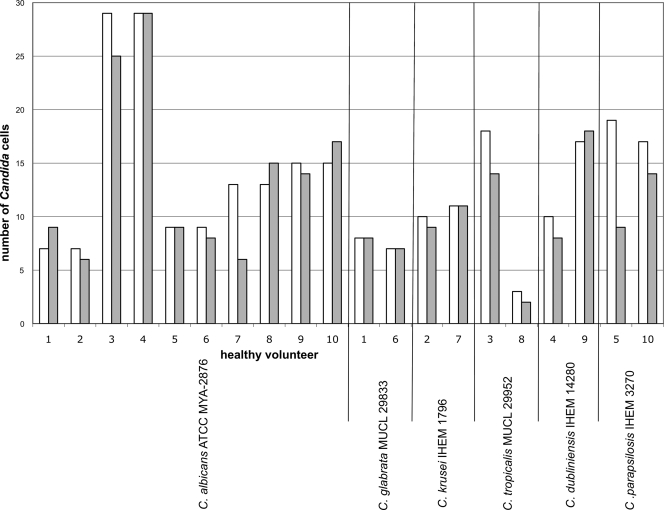

In order to compare the results obtained with IMS/SPC and conventional blood culture, we analyzed spiked blood samples from 10 healthy volunteers in parallel. The average recovery of Candida cells with the IMS/SPC procedure was 95% ± 29% (n = 20) and was independent of the species. The absolute differences in numbers of cells in the spiking solutions and blood samples analyzed by IMS/SPC were very small (Fig. 1). No Candida cells were detected in any of the negative-control samples. A visual color change of the CO2 sensor in all blood culture bottles was seen within 25 h.

FIG. 1.

Numbers of Candida cells in spiking solutions (white bars) compared to the numbers obtained after application of the IMS/SPC procedure to spiked blood samples from 10 healthy volunteers (gray bars).

Storage of blood samples.

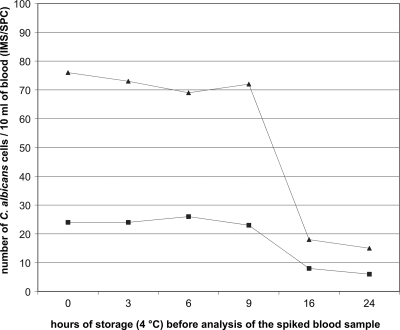

We also determined whether storage (4°C) of blood samples had an influence on the number of yeast cells detected and could not observe a reduction in the number of cells when the sample was analyzed within 9 h of storage (Fig. 2). However, a marked decline (as high as 75%) in the number of cells (independent of the absolute number) was found after 16 h of storage (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Numbers of C. albicans cells obtained with the IMS/SPC procedure for two spiked blood samples from one healthy volunteer (triangles and squares), determined at different time points during storage of the samples at 4°C.

Proof of concept by analysis of clinical samples.

Sixteen clinical samples were analyzed with IMS/SPC and blood culture. Three samples were negative with both methods, six were positive with both methods, and seven were positive with IMS/SPC but negative with blood culture. For some samples, visual and automated detection of a change in color of the indicator on the bottom of the blood culture bottle was performed, and the same results were obtained (data not shown). Additionally, upon subculture, no Candida cells were isolated from any of the negative blood culture bottles.

Absolute counts obtained with IMS/SPC ranged from 2 to 480 Candida cells per ml (Table 2). For two patients, extremely high numbers of Candida cells were found in the blood sample (>175/ml for patient C and 480/ml for patient F). In both cases, a contaminated catheter was removed after collection of the sample. For patient C, a follow-up sample was obtained 9 days after removal of the catheter and the start of anidulafungin treatment. This sample contained fewer cells (2 cells/ml by IMS/SPC analysis) and was no longer positive by blood culture (Table 2).

The differentiation between C. albicans and other Candida species obtained with IMS/SPC was in agreement with the results obtained with culture for the six samples which were positive by both methods (Table 2). For the clinical samples that were negative by blood culture in this study but positive by IMS/SPC, the differentiation between C. albicans and other Candida species obtained with the IMS/SPC assay was in agreement with the identity of the isolate recovered before inclusion in the present study. Patients A, E, K, M, and N presented with mixed infections according to the IMS/SPC analysis, while this was not observed using the culture-based method (Table 1). For patient I, C. glabrata and C. albicans were isolated from a blood culture 3 days before inclusion in our study. With IMS/SPC, only C. albicans cells were found in the sample.

DISCUSSION

We report the development of a 4-h method for the quantification of Candida species in blood, based on IMS and SPC, using viability staining and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to label all Candida species and C. albicans, respectively. Analysis of spiked blood samples indicated that our method is specific, has a low detection limit, and allows accurate quantification.

Using spiked blood samples, we did not observe an improved diagnostic sensitivity with the IMS/SPC method. Unlike the case in numerous reports in literature, all blood cultures of spiked samples were positive (4, 10, 18). This can be explained by the use of laboratory strains to spike the blood cultures. However, seven clinical samples were positive with IMS/SPC but negative with blood culture. The latter observation clearly indicates that the IMS/SPC assay has a higher diagnostic sensitivity than blood culture. For four of the samples for which blood culture was negative but IMS/SPC was positive, treatment with antifungal drugs prior to collection might be an explanation for the divergent results (Table 2).

We observed that analysis of blood samples within 9 h of sample collection is recommended due to a reduction in the number of yeast cells recovered after longer storage. Nevertheless, even for samples that were analyzed more than 9 h after sampling (Table 2), we were able to quantify the number of Candida cells present, although it is likely that the number observed was an underestimation of the number of cells actually present at the time of sampling.

The IMS/SPC method allows not only the rapid diagnosis of candidemia but also the accurate quantification of Candida cells. This might help in assessing the response to antifungal therapy or may lead to the decision to remove intravascular devices (18). Our data suggest that a large number of Candida cells present in a blood sample is associated with a contaminated intravascular device (18), although only two samples were investigated and further research is required to support this hypothesis.

The present study also demonstrates that mixed infections might occur more frequently than generally assumed on the basis of culture-based techniques. While in 5 of the 16 clinical samples C. albicans and at least one other Candida species were found by use of the IMS/SPC procedure, not a single mixed infection was identified by use of blood culture.

Only one previous study has used IMS for the recovery of Candida cells from spiked blood (1). However, this study used culture after capture of the cells, and therefore results were obtained only 1 day before results could normally be obtained with blood culture. Additionally, identification of the Candida species was possible only after culture, and some species were not captured by the antibody. Finally, the low recovery rate (11 to 43%) observed for spiked blood samples was a crucial problem limiting the use of the method for the analysis of clinical samples containing small numbers of Candida cells (1).

Several research groups have obtained good results by PCR on DNA isolated from blood for the diagnosis of candidemia (5, 13, 22). The time to result for a commercial real-time PCR assay (SeptiFast; Roche) is 6 h, which is comparable to that for our method. However, one of the problems of PCR methods is the possible detection of DNA from dead and/or degrading cells instead of living yeasts. To avoid this, a labeling step using the viability stain ChemChrome V6 was included in the SPC procedure described in the present study.

PNA FISH methods are increasingly being used in hospitals for the identification of Candida species after the detection of yeasts in blood culture bottles. In our study, we used a commercially available PNA probe for C. albicans identification, but by using IMS and SPC, we could omit the time-consuming culture step (19). The implementation of additional PNA probes allowing the identification of other Candida species might further improve our method.

In conclusion, our study provides a proof of principle for the diagnostic potential of IMS combined with SPC for the detection of Candida cells in whole blood. In its current form, the method may be too laborious for implementation in a routine diagnostic laboratory. Further automation of the technique combined with an expansion of the panel of pathogens that can be detected and identified in blood could make this technique more attractive for diagnostic laboratories in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Fiandaca from AdvanDx for supplying the PNAFlow kit.

This research was financially supported by the BOF of the Ghent University (project B/07601/02).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apaire-Marchais, V., M. Kempf, C. Lefrancois, A. Marot, P. Licznar, J. Cottin, D. Poulain, and R. Robert. 2008. Evaluation of an immunomagnetic separation method to capture Candida yeast cells in blood. BMC Microbiol. 8:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aurell, H., P. Catala, P. Farge, F. Wallet, M. Le Brun, J. H. Helbig, S. Jarraud, and P. Lebaron. 2004. Rapid detection and enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in hot water systems by solid-phase cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1651-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot, S., G. Dimopoulos, J. Rello, and D. Vogelaers. 2008. Is Candida really a threat in the ICU? Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 14:600-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvath, L. L., B. J. George, and D. R. Hospenthal. 2007. Detection of fifteen species of Candida in an automated blood culture system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3062-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu, M. C., K. W. Chen, H. J. Lo, Y. C. Chen, M. H. Liao, Y. H. Lin, and S. Y. Li. 2003. Species identification of medically important fungi by use of real-time LightCycler PCR. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:1071-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones, J. M. 1990. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:32-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joux, F., and P. Lebaron. 2000. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 2:1523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsu, M., A. Ando, R. Ikedo, Y. Mikari, and N. Kazuko. 2003. Immunomagnetic isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans by beads coated with anti-Cryptococcus serum. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 44:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klouche, M., and U. Schröder. 2008. Rapid methods for diagnosis of bloodstream infections. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 46:888-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, A., S. Mirrett, L. B. Reller, and M. P. Weinstein. 2007. Detection of bloodstream infections in adults: how many blood cultures are needed? J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3546-3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemarchand, K., N. Parthuisot, P. Catala, and P. Lebaron. 2001. Comparative assessment of epifluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry and solid-phase cytometry used in the enumeration of specific bacteria in water. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 25:301-309. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisle, J. T., M. A. Hamilton, A. R. Willse, and G. A. McFeters. 2004. Comparison of fluorescence microscopy and solid-phase cytometry methods for counting bacteria in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5343-5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeffler, J., N. Hence, H. Hebart, D. Schmidt, L. Hagmeyer, U. Schumacher, and H. Einsele. 2000. Quantification of fungal DNA by using fluorescence resonance energy transfer and the Light Cycler system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:586-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mignon-Godefroy, K., J.-G. Guillet, and C. Butor. 1997. Solid phase cytometry for detection of rare events. Cytometry 27:336-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsvik, Ø., T. Popovic, E. Skjerve, K. S. Cudjoe, E. Hornes, J. Ugelstad, and M. Uhlén. 1994. Magnetic separation techniques in diagnostic microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:43-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2002. Role of sentinel surveillance of candidemia: trends in species distribution and antifungal susceptibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3551-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel, R. W., J. R. Coleman, K. D. Miller, and M. J. Feldhaus. 2004. High efficiency recovery and epitope-specific sorting of an scFv yeast display library. J. Immunol. Methods 286:41-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telenti, A., J. M. Steckelberg, L. Stockman, R. S. Edson, and G. D. Roberts. 1991. Quantitative blood cultures in candidemia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 66:1120-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trnovsky, J., W. Merz, P. della-Latta, F. Wu, M. C. Arendrup, and H. Stender. 2008. Rapid and accurate identification of Candida albicans isolates by use of PNA FISHFlow. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1537-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanhee, L. M. E., H. J. Nelis, and T. Coenye. 2009. Detection and quantification of viable airborne bacteria and fungi using solid-phase cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 4:224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wellinghausen, N., D. Siegel, J. Winter, and S. Gebert. 2009. Rapid diagnosis of candidemia by real-time PCR detection of Candida DNA in blood samples. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:1106-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White, P. L., A. Shetty, and R. A. Barnes. 2003. Detection of seven Candida species using the Light-Cycler system. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]