Abstract

Bacillus cereus is found in food, soil, and plants, and the ability to cause food-borne diseases and opportunistic infection presumably varies among strains. Therefore, measuring harmful toxin production, in addition to the detection of the bacterium itself, may be key for food and hospital safety purposes. All previous studies have focused on the main known virulence factors, cereulide, Hbl, Nhe, and CytK. We examined whether other virulence factors may be specific to pathogenic strains. InhA1, NprA, and HlyII have been described as possibly contributing to B. cereus pathogenicity. We report the prevalence and expression profiles of these three new virulence factor genes among 57 B. cereus strains isolated from various sources, including isolates associated with gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal diseases. Using PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR, and virulence in vivo assays, we unraveled these factors as potential markers to differentiate pathogenic from nonpathogenic strains. We show that the hlyII gene is carried only by strains with a pathogenic potential and that the expression levels of inhA1 and nprA are higher in the pathogenic than in the nonpathogenic group of strains studied. These data deliver useful information about the pathogenicity of various B. cereus strains.

Food poisoning is a common yet distressing and sometimes life-threatening problem for millions of people throughout the world. Bacillus cereus is reported to be the fourth major cause of verified food-borne outbreaks in the European Union (4). However, B. cereus-associated outbreaks are likely to be underestimated, as they do not constitute a reportable disease and usually go undiagnosed. If B. cereus is suspected, several identification tests can be performed: morphology tests on selective media, resistance to polymyxin B, lecithinase synthesis, hemolytic capacity, mannitol fermentation, and starch hydrolysis (52). These tests do not, however, reveal whether the isolated strains are pathogenic. The capacity of B. cereus to sporulate and to form biofilms (31, 39) allows the bacterium to resist the usual cleaning procedures used in the food industry, and B. cereus is consequently found in many raw and processed foods, such as rice, spices, milk, vegetables, meat, and various desserts (61). B. cereus can cause two types of food-borne illness, emetic and diarrheal syndromes. The emetic type is characterized by vomiting after a short incubation period of 1 to 6 h and is due to cereulide, a peptide preformed in food (15). The emetic symptoms are similar to those caused by Staphylococcus aureus. The diarrheal type is characterized by abdominal cramps and watery diarrhea occurring within 8 to 16 h after the ingestion of contaminated foods. The clinical symptoms are similar to those caused by Clostridium perfringens (26). In general, both food-borne illnesses are relatively mild, but more-severe cases involving hospitalization or even death have occasionally been reported (46, 47, 61). Interestingly, the spectrum of potential B. cereus toxicity ranges from strains used as probiotics for humans (37) to highly toxic food-poisoning strains (46).

Rare but serious opportunistic nongastrointestinal infections have also been attributed to B. cereus. The main affections observed are endophthalmitis, periodontitis, meningitis, and encephalitis (5, 8, 13, 14, 22, 42). Moreover, a B. cereus strain has caused lethal infections resembling anthrax (36), and several cases of bacteremia in preterm neonates have been described, highlighting this public health problem (35, 49). Infections are characterized by bacterial accumulation despite the induction of inflammation (33, 34). Therefore, B. cereus is able to persist and to counteract the host immune system.

B. cereus produces several secreted toxins, the expression of which is controlled by the pleiotropic transcriptional activator PlcR (23, 44). These include the enterotoxins Hbl and Nhe and the cytotoxin CytK. All three compounds are toxic to Vero cells (18, 32, 45, 46), and there is a strong correlation between the concentration of Nhe in the supernatant of a given strain and cytotoxicity (51). The nhe gene is present in all of the B. cereus strains tested, whereas hbl and cytK are present in less than 50% of randomly sampled strains (1, 16, 38, 53, 56). CytK was originally isolated from the food-borne-outbreak strain NVH 0391/98, which killed three people (46). Nhe and Hbl protein production is higher in clinical and food-poisoning strains than in environmental strains (28). However, deletion of plcR reduces but does not abolish the virulence of the bacterium in various infection models (cultured cells, insects, mice, and rabbits), suggesting that other factors not regulated by PlcR are involved in specific stages during the infection process (7, 54, 57).

For example, the metalloprotease InhA1 provides B. cereus spores with the ability to escape from macrophages and to induce cell mortality (54). InhA1, for which gene expression starts at the onset of stationary phase (25), is secreted and associated with the spore exosporium (9). It has a lethal effect following injection into the insect hemocoel (58) and hydrolyzes cecropin and attacin, two antibacterial proteins found in the hemolymph of insects (12), allowing the bacteria to counteract the host immune system. Bacillus anthracis InhA1 shares 96% identity with InhA1 of B. cereus and is one of the major proteases isolated in the culture supernatant in minimal medium (10). It digests various substrates, including extracellular matrix proteins, and cleaves tissue components, such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen (11). This may help the bacteria to cross the host barrier and gain access to deeper tissues (50).

Another metalloprotease, NprA (bacillolysin, also designated NprB or Npr599 in B. anthracis), for which regulation is also independent of PlcR, represents 60 to 80% of the B. anthracis and B. cereus secretome in a sporulation-favorable medium (10; M. Gohar, personal communication). NprA is part of the thermolysin M4 peptidase family, which also contains pseudolysin, the major Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor. Very few studies have been performed on NprA, but it has been shown to cleave tissue components, such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen, and thus displays characteristics related to pathogenic factors (11). These data suggest that InhA1 and NprA play a significant role in the overall pathogenesis of B. anthracis and B. cereus, by enhancing tissue degradation and by counteracting host defense responses.

Hemolysin II (HlyII) may also play a role during bacterial immune escape. HlyII is, like CytK, a member of the β-barrel pore-forming toxins, such as S. aureus alpha-toxin (24) or C. perfringens β-toxin (60). HlyII hemolytic activity toward rabbit blood cells is over 15 times more potent than that of Staphylococcus alpha-toxin (48). It forms heptameric pores in synthetic lipid bilayers and is hemolytic and cytotoxic to various human cell lines (2, 3). HlyII induces apoptosis in human and mouse macrophages and is strongly implicated in B. cereus virulence toward mice and insects (S. Tran, E. Guillemet, C. Clybouw, A. Moris, M. Gohar, D. Lereclus, and N. Ramarao, submitted for publication).

The objective of this study was to identify genetic determinants specific to pathogenic strains. We report the prevalence and expression profiles of three new virulence factor genes, inhA1, nprA, and hlyII, among a panel of strains representative of B. cereus diversity and showing different pathogenic profiles. Using PCR and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-qPCR), we highlight these factors as potential markers to differentiate pathogenic from nonpathogenic strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

This study includes 57 Bacillus cereus strains isolated from various sources (Table 1). The panel of strains was chosen to be representative of the various pathogenic profiles found among the B. cereus group: strains associated with food poisoning (19 isolates associated with diarrheal or emetic outbreaks), strains associated with other clinical diseases (20 isolates from human samples associated with nongastrointestinal infection), and strains not associated with diseases (18 isolates from the environment or from food samples with no collective food-borne-poisoning history). Strains not associated with disease were all low-Nhe producers, as measured by a Tecra test kit (Bacillus diarrheal enterotoxin visual immunoassay), and low-Hbl producers, as measured by an Oxoid test kit (BCET-RPLA toxin detection kit) as reported in reference 28. They were presumed to be nonpathogenic. In contrast, strains associated with food poisoning were all high-Nhe producers (15, 17, 28). Strains were selected from the six major B. cereus phylogenetic groups (groups II to VII as defined in reference 30) to obtain a strain collection representative of B. cereus diversity. Most strains not associated with disease were affiliated with group VI; moreover, there were no strains associated with food-borne diseases or clinical infection from group VI, as previously observed (30).

TABLE 1.

Strain table and detection of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII genes by PCR and Southern blotting

| Pathogenic profile and genetic group | Strain | Source | Reference or sourcea | Detection of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inhA1 | nprA | hlyII | ||||

| Nonpathogenic | ||||||

| II | INRA BC′ | Vegetable | 28 | + | + | − |

| III | INRA PF | Milk protein | 28, 30 | + | + | − |

| IV | INRA A3 | Starch | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − |

| VI | INRA 1 | Pasteurized purée | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − |

| INRA 5 | Pasteurized purée | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| INRA BK | Vegetable | 28 | + | + | − | |

| INRA BL | Vegetable | 28 | + | + | − | |

| INRA C1 | Pasteurized vegetables | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| INRA C46 | Pasteurized vegetables | 28 | + | + | − | |

| INRA C64 | Pasteurized vegetables | 28 | + | + | − | |

| INRA C74 | Pasteurized vegetables | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| ADRIA I3 | Cooked foods | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| ADRIA I20 | Cooked foods | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| ADRIA I21 | Cooked foods | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| INRA SL′ | Soil | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| INRA SO | Soil | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| INRA SV | Soil | 28, 30 | + | + | − | |

| WSBC 10204 | Pasteurized milk | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| Food poisoning | ||||||

| II | NVH 0861/00 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − |

| III | NVH 0500/00 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + |

| NVH 0075/95 | Diarrheal outbreak | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| 06 ceb 04 bac | Emetic outbreak | This study | + | + | − | |

| NVH 1519/00 | Diarrheal outbreak | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| 198R 2003 | Emetic outbreak | This study | + | + | − | |

| F3371/93 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + | |

| F4433/73 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| F4810/72 | Emetic outbreak | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| LMG 17615 (F289/78) | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 16 | + | + | + | |

| NC 7401 | Emetic outbreak | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| NVH 200 | Diarrheal outbreak | 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| IV | NVH 0230/00 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − |

| NVH 1230/88 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + | |

| 98HMPL63 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| F2081A/98 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + | |

| F352/90 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + | |

| F4430/73 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | − | |

| VII | NVH 0391/98 | Diarrheal outbreak | 28, 30, 46, 16 | + | + | − |

| Clinical, nongastrointestinal infection | ||||||

| II | AH1125 | Human | § | + | + | + |

| III | DSM 4222 (F837/76) | Human, postoperative infection | 28, 30, 16 | + | + | + |

| AH728 | Human, urine | § | + | + | − | |

| AH825 | Human, periodontitis | § | + | + | − | |

| AH891 | Human, blood | § | + | + | − | |

| AH893 | Human, wound | § | + | + | − | |

| AH1127 | Human, eye | § | + | + | − | |

| AH1131 | Human, eye | § | + | + | + | |

| B06_007 | Human, cutaneous | § | + | + | − | |

| B06_018 | Human, peritoneal | § | + | + | − | |

| IV | AH716 | Human, pus | § | + | + | − |

| AH726 | Human, urine | § | + | + | − | |

| AH815 | Human, periodontitis | § | + | + | + | |

| AH1129 | Human, eye | § | + | + | − | |

| AH1293 | Human, blood | § | + | + | + | |

| B06_019 | Human, wound | § | + | + | − | |

| B06_034 | Human | § | + | + | − | |

| B06_036 | Human, blood | § | + | + | − | |

| V | AH1308 | Human, feces | § | + | + | − |

| B06_015 | Human, drainage tube | § | + | + | − | |

§, University of Oslo's Bacillus cereus group multilocus sequence typing Website (http://mlstoslo.uio.no).

Detection of the virulence factor genes by PCR. (i) Primer design.

For PCR primer design, nucleotide sequences from available databases were aligned to identify regions that were conserved across all strains and regions that differed within paralogous genes. Indeed, in silico analysis revealed the presence of up to three zinc metalloproteases that were highly similar to inhA1 (around 66% identity) in the genomes of various strains (inhA2, inhA3, and inhA4) (41, 27). Several strains possessed the nprA paralogue nprB (41). Moreover, inhA1 is characterized by a high degree of sequence polymorphism between the strains; thus, some bases had to be replaced with inosine (which can pair with A, C, or T) or a degenerate sequence had to be used to account for all cases of genetic variability. In some strains, if the targeted gene had not been detected with the first primer pair, a second screen was performed with another primer pair (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of primers used in this study

| Primer purpose and target gene (locus taga) | Primerb | Primer sequencec (5′-3′) | Location within genea | Annealing temp (°C) | Product size (bp) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR for inhA1, nprA, and hlyII detection | ||||||

| inhA1 (BC1284) | F-inhA1-d1 | ACGCITTIAAATTTGCICG | 1937-1955 | 55 | 257 | This study |

| R-inhA1-d1 | ACGCGTTGGAGATACAACTT | 2193-2174 | ||||

| F-inhA1-d2 | CCAGCTTGGAAAGTTGTATC | 2164-2183 | 55 | 166 | This study | |

| R-inhA1-d2 | CAGCTTGTCCTACTACTTCA | 2329-2310 | ||||

| nprA (BC0602) | F-nprA-d | GTATACGGAGATGGTGATGG | 1111-1130 | 55 | 263 | This study |

| R-nprA-d | GGATCACTCATAGAGCGAAG | 1373-1354 | ||||

| hlyII (BC3523) | Fhly-II | GATTCTAAAGGAACTGTAG | 94-112 | 48 | 868 | 19 |

| Rhly-II | GGTTATCAAGAGTAACTTG | 961-943 | ||||

| F-hlyII-d | CAAGTTACTCTTGATAACC | 943-961 | 48 | 194 | This study | |

| R-hlyII-dq | TCACCATTTACAAAGATACC | 1136-1117 | ||||

| PCR amplification of hlyII probe | ||||||

| hlyII (BC3523) | F-hlyII-p | GCATTTGCAGATTCTAAAGG | 85-104 | 55 | 1,019 | This study |

| R-hlyII-p | TCGTAACTGATACCATAACC | 1103-1084 | ||||

| RT-qPCR | ||||||

| inhA1 (BC1284) | F-inhA1-q | GATAAAAC(A/G)CCAGCTTGGAAAG | 2155-2176 | 60 | 189 | This study |

| R-inhA1-q | TGCAGA(A/T)TTATCATCAGCTTG | 2343-2323 | ||||

| nprA (BC0602) | F-nprA-q | TGCAGCAGCAGTAGATGCTC | 951-970 | 60 | 188 | This study |

| R-nprA-q | ATGTTACACCATCACCATC | 1138-1120 | ||||

| hlyII (BC3523) | F-hlyII-q | CTGGAAAAACCATCAAGTTACTC | 930-952 | 60 | 207 | This study |

| R-hlyII-dq | TCACCATTTACAAAGATACC | 1136-1117 | ||||

| rpoA (BC0158) | F-rpoA-q | TAACTCCTTACGTCGTATTC | 111-130 | 60 | 186 | This study |

| R-rpoA-q | ATTTCCAACGTCTTCTCTTC | 296-277 | ||||

| rpoB (BC0122) | F-rpoB-q | TCAGTGGTTTCTTGATGAGG | 111-130 | 60 | 176 | This study |

| R-rpoB-q | CTTTTACACGAAGTGGTGCT | 286-267 |

Reference strain Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 (NCBI accession no. NC_004722).

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

I, inosine.

(ii) DNA extraction and PCR.

The genomic DNA from each strain was prepared as previously described (29), with minor modifications. Briefly, bacteria were grown on LB agar plates overnight at 32°C. Bacteria were collected from the plates, resuspended in extraction buffer (1.7% SDS, 200 mM Tris, pH 8, 20 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl), and incubated at 55°C for 1 h with proteinase K. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, washed with ethanol, dissolved in sterile MilliQ water, and treated with RNase for 15 min. DNA was quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

The PCR mixture for gene detection contained 50 to 125 ng DNA, 1 μM primer (forward and reverse), 1.2 U RedGoldStar DNA polymerase (Eurogentec), 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix, and 1× buffer supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 in a final volume of 15 μl. Thermal cycling was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems) with the following program: a start cycle of 3 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at the annealing temperature (Table 2), and 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension time of 5 min at 72°C. PCR fragment sizes were revealed on 2% agarose gels.

Detection of the hlyII gene by Southern dot blot assay.

Strains that were negative for hlyII in PCR experiments were subjected to Southern dot blotting. Strains with sequenced genomes were included as positive and negative controls. We generated a biotinylated probe by PCR amplification of the hlyII gene using the primer pair F-hlyII-p and R-hlyII-p (Table 2) and the ATCC 14579 strain as template. The reaction mixture contained 0.7 μM primers, 200 μM dNTPs, and 68 μM biotin-11-dUTP (Fermentas), and the amplification was performed with high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase (Roche).

Three micrograms of genomic DNA of each strain to be tested was denatured by heating at 98°C for 6 min, spotted onto a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham), and fixed under UV light (0.150 J/cm2). Denatured probe at a concentration of 30 ng/ml was hybridized to membranes for 4 h in Rapid-hyb buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham). The membranes were washed, and then genomic DNA-biotinylated probe complexes were revealed with a biotin chromogenic kit (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's protocol; a deep purple coloration indicated spots in which the hlyII gene was present.

Quantification of virulence factor expression by RT-qPCR.

The amounts of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII transcripts in each strain were measured by RT-qPCR. The expression levels of the three genes were calculated based on the comparative quantification cycle (Cq) method and relative to the mean expression of two housekeeping genes, rpoA and rpoB, used as endogenous references. The whole experiment (from strain culture to RT-qPCRs) was performed twice for empirical assessment of accuracy and repeatability.

(i) Strain culture and preparation.

Bacteria were cultivated overnight in standard LB medium. Fresh LB or sporulation-specific medium (43) was then inoculated with the overnight culture and grown for 105 min, by which time all strains were in exponential growth phase. The synchronized cultures were inoculated at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.02 in LB or in sporulation medium in identical test tubes and incubated in a 32°C water bath with agitation. After exactly 6 h of incubation, a 1-ml sample was taken from each culture and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C, and the bacterial pellet was placed immediately at −80°C until processing.

(ii) RNA extraction.

B. cereus cells, thawed in 500 μl of TRI reagent (Ambion), were disrupted by bead beating (FastPrep; MP Biomedicals) with about 350 mg of 0.1-mm-diameter silica beads (lysing matrix B; MP Biomedicals). RNA was separated from proteins by adding chloroform and was purified with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Remaining traces of DNA were eliminated by two rounds of DNase treatment (TURBO DNA-free kit; Ambion). RT-qPCR controls without reverse transcriptase showed that no genomic DNA was detectable in the RNA samples. The concentration of RNA was assessed by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop; Thermo Scientific). Between 10 and 30 μg of RNA were recovered from a 1-ml bacterial culture.

(iii) RNA purity and quality and determination of the RIN.

The purity and integrity of RNA are critical elements for the overall success of RNA-based analyses. We measured the ratio of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. All RNA samples had an OD260/OD280 ratio of ≥1.95, which is considered a good indicator of RNA purity (40). Moreover, RNA integrity was further examined by measuring the RNA integrity number (RIN) using a user-independent strategy. The RIN algorithm allows the calculation of RNA integrity using a trained artificial neural network based on the determination of various features. These variables include the total RNA ratio (ratio of the area of ribosomal bands to the total area of the electropherogram) and the height of the 16S and 23S peaks (40). The RIN was calculated for a representative set of strains and was between 7 and 9.6. RIN values above 5 indicated RNA samples that were of very good quality (21).

(iv) Primer design.

The primers used for RT-qPCR experiments were designed to amplify specific gene fragments of 170 to 210 bp (Table 2). The efficiency of the primer pairs was determined experimentally on one representative strain of each genetic group by measuring the Cq of each RNA sample over a 4-log RNA dilution (6). Primer pairs with an efficiency of ≤85% were eliminated. In the case of inhA1, several primer pairs were tested but none of the pairs could be validated for all strains. The primers chosen, F-inhA1-q and R-inhA1-q, were validated for the genetic groups II, III, IV, and VI (efficiency of >85%) but were not suitable to quantify inhA1 expression in strains belonging to genetic groups V and VII (3 strains out of 57).

Primer specificity was validated by sequencing the amplification product obtained for the target and reference genes of one representative strain in each genetic group (data not shown).

(v) RT-qPCR experiments and analysis.

We used the mean expression values of two reference genes to normalize our data, as suggested in several publications (6, 63). Thereafter, target gene amounts measured by RT-qPCR were normalized against the amounts of rpoA and rpoB genes, for which the difference in the mean Cq between strains from the three pathogenic profiles was <0.08.

Target and reference gene mRNA abundance was measured by one-step RT-qPCR with a QuantiFast SYBR green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). RT-qPCRs and cycling were set up as recommended by the manufacturer. RT-qPCR samples contained 1 ng of RNA and 1 μM each primer in a final volume of 25 μl and were run in a LightCycler 480 (Roche) in 96-well plates. Expression levels of the target genes relative to the endogenous standard were calculated using the basic relative quantification method (Roche) and the LightCycler 480 software. All RT-qPCRs were performed in duplicate and repeated if the Cq difference between both duplicates exceeded 0.5. For each strain and each gene, the mean expression value of the two experiments carried out in duplicate was calculated and spotted as a single value. All plates also contained a positive control (control RNA sample loaded on each plate) to detect interrun variations.

The specificity of each amplification reaction was verified with the melting curve profile (55): a single peak was obtained, attesting to the amplification of a unique product. For each gene, a control with no RNA template (no-template control) was included in all plates to check for the absence of reagent contamination or small amounts of primer dimeric forms.

Insects and in vivo experiments.

Infection by injection into the hemolymph of Galleria mellonella larvae was performed as described previously (20, 27, 57). Ten-microliter suspensions containing 104 B. cereus vegetative bacteria were injected onto the base of the last proleg of groups of 20 last-instar larvae. All tests were run twice. Insect mortality was recorded after a 24-h incubation time at 32°C.

Cell culture and toxicity.

The cytotoxicity of B. cereus cell-free supernatant, collected after 6 h of culture in LB medium, to J774 murine macrophage-like cells was assessed as previously described (54).

Statistics.

For statistical analysis of RT-qPCR results, we determined the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient and carried out the Mann-Whitney test using Statext software (www.statext.com).

RESULTS

Prevalence of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII genes among pathogenic and nonpathogenic B. cereus strains.

The prevalence of the three virulence factor genes inhA1, nprA, and hlyII among our panel of 57 B. cereus isolates was investigated by PCR (Table 1). With inhA1- and nprA-targeting primers, a PCR product of the expected size was amplified from all strains, indicating that the inhA1 and nprA genes are present in all strains tested. In the case of hlyII, amplification was observed for 11 of the 57 strains studied. The absence of hlyII from all other isolates was confirmed by Southern blotting (not shown).

Thus, inhA1 and nprA genes were carried by all strains studied, whereas hlyII was found in only 19% of them (Table 1). Interestingly, the distribution of hlyII was unequal among the three groups: none of the strains affiliated to the nonpathogenic group carried the hlyII gene, whereas it was present in 6/19 food-poisoning and in 5/20 clinical strains (Table 1). Thus, hlyII was not found in nonpathogenic strains and its prevalence among pathogenic strains, isolated from food-poisoning outbreaks or clinical infections, was around 30%.

Quantification of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII expression in B. cereus strains.

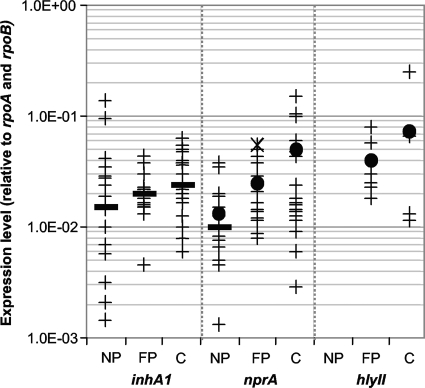

It has often been suggested that the expression level rather than the mere presence of genes encoding virulence factors accounts for most B. cereus pathogenic potential (28, 51). This study sought, therefore, to measure and compare the expression profiles of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII in pathogenic and nonpathogenic B. cereus isolates (Fig. 1). We calculated the mean expression value of two independent experiments, done in duplicate, for each strain and for each gene. Moreover, we also calculated the mean and median gene expression values for each pathogenic group.

FIG. 1.

Expression profiles of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII among B. cereus strains. Logarithmic representation of the expression levels of inhA1, nprA, and hlyII among 57 (54 for inhA1) B. cereus nonpathogenic (NP), food-poisoning (FP), and clinical (C) strains normalized to the mean expression value of the two reference genes rpoA and rpoB. For each strain, the mean value of two independent experiments done in duplicate is represented as a cross. For each pathogenic profile, the mean value is represented as a dot and the median value as a bold line. The × symbol represents the nprA expression level of the NVH 0391/98 strain.

(i) nprA expression.

There is a clear difference in nprA expression profiles between nonpathogenic and pathogenic strains (food poisoning and clinical) (P < 0.002). The mean expression values were 2- and 3-fold greater for food-borne and clinical infection strains, respectively, than for nonpathogenic strains. The median nprA expression value (middle value of the distribution, for which 50% of the strains have superior values and 50% of the strains have inferior values) also provided an interesting indicator. It was used to evaluate the number of pathogenic strains with high nprA expression levels (high NprA producers were defined as strains for which the expression value is superior to the nonpathogenic strain median value). In both pathogenic groups, from food-borne and clinical infections, over 85% of the strains were high-NprA producers. Interestingly, strain NVH 0391/98, which was isolated from a fatal food-poisoning outbreak, had the highest nprA expression level among strains associated with diarrhea (× symbol in Fig. 1).

The results were similar for strains cultured in sporulation-specific medium: 100% of food-borne and 80% of clinical infection-associated strains were high-NprA producers (not shown). In this medium, on average, the expression values were 5- to 14-fold higher than in LB medium, suggesting that the nprA gene was expressed better in a relatively poor, sporulation-specific medium, in which NprA is the major secreted protein at this physiological stage (10).

(ii) inhA1 expression.

In the case of inhA1 expression, the mean value for nonpathogenic strains was not statistically different from the mean value for pathogenic strains. However, for this gene, the expression profiles of nonpathogenic strains varied significantly from strain to strain and there were up to 100-fold differences in transcript abundance between isolates. Thereafter, the median value rather than the mean value of each group was considered. Seventy percent of both food-borne and clinical pathogenic strains were high-InhA1 producers, i.e., had expression values superior to the nonpathogenic strain median value.

(iii) hlyII expression.

Nonpathogenic strains do not carry the hlyII gene; thus, we could not compare mean or median expression values between pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains. However, the mean hlyII expression value for clinical strains was 2-fold higher than the mean value for strains associated with food poisoning, as observed for nprA expression.

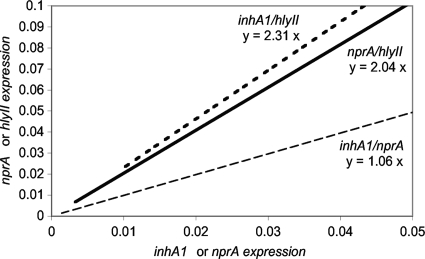

(iv) Relative inhA1, nprA, and hlyII expression.

In all the strains carrying them, the inhA1, nprA, and hlyII genes were expressed, although not at the same level, depending on the strain. The expression levels of the two metalloproteases genes inhA1 and nprA in LB medium appeared to be closely related in all strains (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, P < 0.001). Indeed, if for each strain the inhA1 expression value (x axis) was plotted against the nprA expression value (y axis), the average ratio of expression of inhA1 to nprA was 1 (Fig. 2), and almost all the strains had values that were close to the regression line. Thereafter, for a given strain, the expression profiles for inhA1 and nprA were similar and a strain was either a high or a low producer of both metalloproteases.

FIG. 2.

Relative expression profiles. For each strain, the inhA1 (x axis) expression value was plotted against the nprA (y axis, gray dashed line) or the hlyII (dark dashed line) expression value. Alternatively, nprA expression values (x axis) were plotted against the hlyII values (y axis, plain line). The regression line was drawn, and the average ratio between expression values was calculated.

We observed a similar trend among strains with hlyII expression (Fig. 2), even though the correlation coefficient calculated with this third gene was slightly weaker (P < 0.05) due to the limited available data, as only 11 isolates were found to be hlyII positive. For these strains, the ratio of hlyII to inhA1 was 2.3 and the ratio of hlyII to nprA was 2. This suggests that when a strain expresses one of these genes to a high level, first, it also has high expression of the other two genes, and second, it expresses twice as much hlyII as inhA1 and nprA.

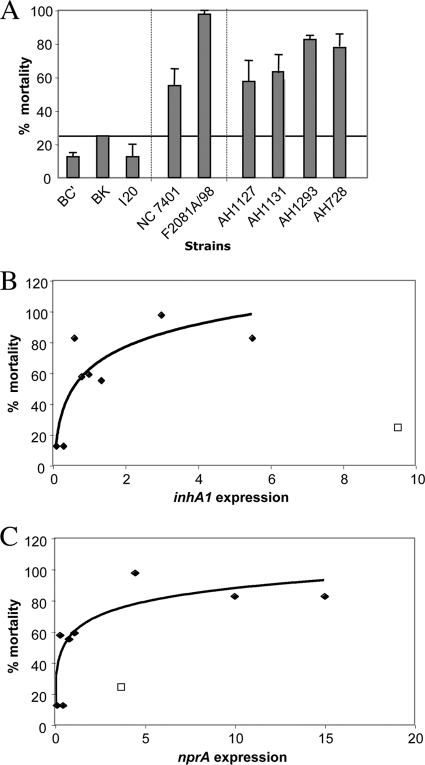

Virulence of nonpathogenic and pathogenic strains in G. mellonella insects.

Nine strains, belonging to the three pathogenic groups and with various inhA1, nprA, and hlyII expression profiles, were tested for their virulence by injection into the hemocoel of G. mellonella larvae (Fig. 3A). Nonpathogenic strains were all avirulent (less than 25% mortality). In contrast to nonpathogenic strains, clinical pathogenic strains and those associated with food poisoning were all virulent (inducing 55% to 98% mortality).

FIG. 3.

Virulence of strains to G. mellonella insects and expression correlations. Nine strains were tested for their virulence toward G. mellonella insects by injection into the insect larvae hemocoel. (A) Mortality was recorded 24 h postinfection. Error bars show standard deviations of the means of the results from two independent experiments. (B and C) A logarithmic regression line represents the correlation between levels of inhA1 (B) or nprA (C) expression of these strains and virulence. The square represents the BK strain, for which data were not included in the regression line calculation. Black diamonds represent all of the other strains that were tested for virulence.

All strains containing hlyII (F2081A/98, AH1293, and AH1131) were strongly virulent to insects, suggesting that HlyII may be a good indicator of pathogenicity. However, several hlyII-negative strains were still virulent (3/6 in the insect infection test and 70 to 75% of the food poisoning and clinical isolates), indicating that the induction of diseases is probably multifactorial.

We observed good correlation between the expression levels of inhA1 (Fig. 3B) and nprA (Fig. 3C), and virulence in G. mellonella insects for eight of the nine strains tested. Thus, high-InhA1 and -NprA producers are likely to be highly pathogenic to G. mellonella insects, as also observed for the two food-poisoning and clinical pathogenic strain profiles. We consistently found the two most virulent strains, F2081A/98 and AH1293 (mortality of >77%), to be high-NprA, -InhA1, and -HlyII producers. Moreover, five of the six virulent strains carried the hlyII gene and/or were high-NprA producers. Thus, it appears that InhA1, NprA, and HlyII confer an advantage on the strains expressing them to establish an infection.

DISCUSSION

Altogether, we show that the hlyII gene is present in only 19% of the strains. This is consistent with a study by Fagerlund et al. (19) in which hlyII was detected in 6 of the 29 (21%) B. cereus strains tested. We further show that hlyII is found only in pathogenic strains isolated from food-poisoning outbreaks or clinical infections. This is the first example of a B. cereus gene that is clearly present only in pathogenic strains. This sheds further light on the important role of hemolysin II and highlights that the presence of the hlyII gene may be a good indicator of pathogenicity. However, as only 30% of pathogenic strains carry hlyII, the absence of hlyII cannot be interpreted as absence of pathogenicity.

In addition, we show that the two genes inhA1 and nprA, encoding two zinc metalloproteases implicated in B. anthracis and B. cereus pathogenesis, are carried by all strains studied but are expressed at a higher level in pathogenic strains, especially in strains associated with clinical nongastrointestinal disease.

It appears that B. cereus may use the three virulence factors InhA1, NprA, and HlyII (when present) simultaneously rather than separately. Indeed, we observed correlations between the expression levels of the three factors, first, with one another, and second, with virulence to insects, suggesting that B. cereus likely uses these factors concomitantly during pathogenicity. Although it is not possible to discriminate pathogenic from nonpathogenic strains based on their inhA1 or nprA expression levels alone, as the expression profiles of the groups partially overlap, on average, pathogenic strains express inhA1, nprA, and hlyII to higher levels than nonpathogenic strains. Thus, we speculate that the expression of these genes may confer an advantage on the strains carrying them for their ability to induce infection.

The expression levels of these three genes had never been studied before, as all the previous works have focused mainly on the main known virulence factors, Hbl, Nhe, CytK, and cereulide (1, 16, 38, 53, 56). B. cereus causes many different pathologies, and the importance of each virulence factor may vary accordingly. For instance, the diarrheal disease is attributed to enterotoxins because B. cereus culture filtrates cause fluid accumulation in rabbit ileal loop (59). The toxins may elicit diarrhea by inducing membrane permeability of epithelial cells in the small intestine. Hbl, Nhe, and CytK are all toxic to Vero cells and are considered good diarrheal toxin candidates. InhA1, NprA, and HlyII may play a role in addition to the enterotoxins. InhA1 and NprA are proteases cleaving various membrane components (11), and HlyII has cytotoxic and hemolytic activities (2). These properties may allow the bacteria to gain access to deeper tissues and to disseminate.

In the case of nongastrointestinal clinical infections, several strains express inhA1, nprA, and hlyII at very high levels. Among these, the strains isolated from human blood (AH1293, AH891, B06_036, and B06_019) express inhA1 and nprA to a higher level than strains isolated from the eye (AH1127 and AH1131). These strains induce nongastrointestinal diseases and may therefore enter the blood system quickly after infection. To persist inside the host, these strains will have to survive the bactericidal action of phagocytes. Phagocytes, such as macrophages, are essential effectors of the immune response against infective microorganisms, as they engulf pathogens and activate the late immune response. InhA1, NprA, and HlyII are likely to be involved in the bacterial capacity to counteract the host immune system. In particular, InhA1 allows the bacteria to escape from macrophages (54), HlyII induces macrophage mortality (Tran et al., submitted), and InhA1 and NprA cleave various host cell components (11). These properties may therefore confer an advantage on strains expressing these genes, in their capacity to induce severe clinical diseases.

We hope that our findings on InhA1, NprA, and HlyII and the RT-qPCR methods allowing quantification of the expression of toxin genes will improve knowledge of B. cereus factors implicated in diseases for better clinical diagnosis and food safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stéphanie Gagnier for excellent technical assistance. We thank Agnès Fouet and Patricia Sylvestre for strain transfer. We thank Christophe Buisson for his help with the bio-assays. We thank Jordan Madic, Pierre Micheau, Eugénie Huillet, and Jacques Mahillon for helpful discussion. RIN analyses were performed at INRA, Jouy en Josas, on the PiCT-Gem platform. We thank the PCR platform at AFSSA-LERQAP for the use of the Roche LC480.

C.C. had an INRA-AFSSA grant, and this work was supported by grants ANR-05-PNRA-013 and INRA-AFSSA-Tiacer.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson Borge, G. I., M. Skeie, T. Sorhaug, T. Langsrud, and P. E. Granum. 2001. Growth and toxin profiles of Bacillus cereus isolated from different food sources. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 69:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreeva, Z., V. Nesterenko, M. Fomkina, V. Ternosky, N. Suzina, A. Bakulina, A. Solonin, and E. Sineva. 2007. The properties of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II pores depend on environmental conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreeva, Z., V. Nesterenko, I. Yurkov, Z. I. Budarina, E. Sineva, and A. S. Solonin. 2006. Purification and cytotoxic properties of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II. Protein Expr. Purif. 47:186-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. 2009. The community summary report on food-borne outbreaks in the European Union in 2007. The EFSA J. 2009(May):271. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnaout, M., R. Tamburro, S. Bodner, J. Sandlund, G. Rivera, and C. Pui. 1999. Bacillus cereus causing fulminant sepsis and hemolysis in two patients with acute leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 21:431-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin, S., V. Benes, J. Garson, J. Hellemans, J. Huggett, M. Kubista, R. Mueller, T. Nolan, M. Pfaffl, G. Shipley, J. Vandesompele, and C. Wittwer. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55:611-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callegan, M. C., S. T. Kane, D. C. Cochran, M. S. Gilmore, M. Gominet, and D. Lereclus. 2003. Relationship of PlcR-regulated factors to Bacillus endophthalmitis virulence. Infect. Immun. 71:3116-3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callegan, M. C., S. T. Kane, D. C. Cochran, B. Novosad, M. S. Gilmore, M. Gominet, and D. Lereclus. 2005. Bacillus endophthalmitis: roles of bacterial toxins and motility during infection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46:3233-3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlton, S., A. J. Baillie, and A. Moir. 1999. Characterisation of exosporium of Bacillus cereus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitlaru, T., O. Gat, Y. Gozlan, N. Ariel, and A. Shafferman. 2006. Differential proteomic analysis of the Bacillus anthracis secretome: distinct plasmid and chromosome CO2-dependent cross talk mechanisms modulate extracellular proteolytic activities. J. Bacteriol. 188:3551-3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, M. C., T. G. Popova, B. A. Millis, D. V. Mukherjee, W. Zhou, L. A. Liotta, E. F. Petricoin, V. Chandhoke, C. Bailey, and S. G. Popov. 2006. Secreted neutral metalloproteases of Bacillus anthracis as candidate pathogenic factors. J. Biol. Chem. 281:31408-31418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalhammar, G., and H. Steiner. 1984. Characterization of inhibitor A, a protease from Bacillus thuringiensis which degrades attacins and cecropins, two classes of antibacterial proteins in insects. Eur. J. Biochem. 139:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damgaard, P. H., P. E. Granum, J. Bresciani, M. V. Torregrossa, J. Eilenberg, and L. Valentino. 1997. Characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from infections in burn wounds. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 18:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dancer, S. J., D. McNair, P. Finn, and A. B. Kolstø. 2002. Bacillus cereus cellulitis from contaminated heroin. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:278-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehling-Schulz, M., M. H. Guinebretière, A. Monthan, O. Berge, M. Fricker, and B. Svensson. 2006. Toxin gene profiling of enterotoxic and emetic Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 260:232-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehling-Schulz, M., B. Svensson, M. H. Guinebretière, T. Lindbäck, M. Andersson, A. Schulz, M. Fricker, A. Christiansson, P. E. Granum, E. Märtlbauer, C. Nguyen-The, M. Salkinoja-Salonen, and S. Scherer. 2005. Emetic toxin formation of Bacillus cereus is restricted to a single evolutionary lineage of closely related strains. Microbiology 151:183-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagerlund, A., J. Brillard, R. Fürst, M. H. Guinebretiere, and P. E. Granum. 2007. Toxin production in a rare and genetically remote cluster of strains of the Bacillus cereus group. BMC Microbiol. 7:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagerlund, A., T. Lindbäck, A. Storset, P. E. Granum, and S. P. Hardy. 2008. Bacillus cereus Nhe is a pore forming toxin with structural and functional properties similar to ClyA (HlyE, SheA) family of haemolysins, able to induce osmotic lysis in epithelia. Microbiology 154:693-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fagerlund, A., O. Ween, T. Lund, S. P. Hardy, and P. E. Granum. 2004. Genetic and functional analysis of the cytK family genes in Bacillus cereus. Microbiology 150:2689-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedhila, S., P. Nel, and D. Lereclus. 2002. The InhA2 metalloprotease of Bacillus thuringiensis strain 407 is required for pathogenicity in insects infected via the oral route. J. Bacteriol. 184:3296-3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleige, S., and M. W. Pfaffl. 2006. RNA integrity and the effect on real time qRT-PCR performance. Mol. Aspects Med. 27:126-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankard, J., R. Li, F. Taccone, M. J. Struelens, F. Jacobs, and A. Kentos. 2004. Bacillus cereus pneumonia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23:725-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gohar, M., K. Faegri, S. Perchat, S. Ravnum, O. A. Økstad, A. B. Kolstø, and D. Lereclus. 2008. The PlcR virulence regulon of Bacillus cereus. PLoS One 3:e2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouaux, E. 1998. Alpha hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus: an archetype of beta barrel, channel forming toxins. J. Struct. Biol. 121:110-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandvalet, C., M. Gominet, and D. Lereclus. 2001. Identification of genes involved in the activation of the Bacillus thuringiensis inhA metalloprotease gene at the onset of sporulation. Microbiology 147:1805-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granum, P. E., and T. Lund. 1997. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillemet, E., C. Cadot, S. Tran, M. H. Guinebretière, D. Lereclus, and N. Ramarao. 2010. The InhA metalloproteases of B. cereus contribute concomitantly to virulence. J. Bacteriol. 192:286-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guinebretière, M. H., V. Broussolle, and C. Nguyen-The. 2002. Enterotoxigenic profiles of food-poisoning and food-borne Bacillus cereus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3053-3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guinebretiere, M. H., and C. Nguyen-The. 2003. Sources of Bacillus cereus contamination in a pasteurized zucchini purée processing line, differentiated by two PCR-based methods. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 43:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guinebretière, M. H., F. L. Thompson, A. Sorokin, P. Normand, P. Dawyndt, M. Ehling-Schulz, B. Svensson, V. Sanchis, C. Nguyen-The, M. Heyndrickx, and P. De Vos. 2008. Ecological diversification in the Bacillus cereus group. Environ. Microbiol. 10:851-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall-Stoodley, L., and P. Stoodley. 2009. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1034-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy, S. P., T. Lund, and P. E. Granum. 2001. CytK toxin of Bacillus cereus forms pores in planar lipid bilayers and is cytotoxic to intestinal epithelia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 197:47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez, E., F. Ramisse, T. Cruel, R. le Vagueresse, and J. D. Cavallo. 1999. Bacillus thuringiensis serotype H34 isolated from human and insecticidal strains serotypes 3a3b and H14 can lead to death of immunocompetent mice after pulmonary infection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 24:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernandez, E., F. Ramisse, J. P. Ducoureau, T. Cruel, and J. D. Cavallo. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. konkukian (serotype H34) superinfection: case report and experimental evidence of pathogenicity in immunosuppressed mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2138-2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilliard, N. J., R. L. Schelonka, and K. B. Waites. 2003. Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a preterm neonate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3441-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmaster, A. R., J. Ravel, D. A. Rasko, G. D. Chapman, M. D. Chute, C. K. Marston, B. K. De, C. T. Sacchi, C. Fitzgerald, L. W. Mayer, M. C. Maiden, F. G. Priest, M. Barker, L. Jiang, R. Z. Cer, J. Rilstone, S. N. Peterson, R. S. Weyant, D. R. Galloway, T. D. Read, T. Popovic, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. Identification of anthrax toxin genes in a Bacillus cereus associated with an illness resembling inhalation anthrax. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:8449-8454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong, H., H. Le Duc, and S. Cutting. 2005. The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:813-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh, Y., S. Sheu, Y. Chen, and H. Tsen. 1999. Enterotoxigenic profiles and polymerase chain reaction detection of Bacillus cereus group cells and B. cereus strains from foods and food-borne outbreaks. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:481-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsueh, Y., E. Somers, D. Lereclus, and A. C. Wong. 2006. Biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus is influenced by PlcR, a pleiotropic regulator. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5089-5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imbeaud, S., E. Graudens, V. Boulanger, X. Barlet, P. E. Zaborski, O. Mueller, A. Schroeder, and C. Auffray. 2005. Towards standardization of RNA quality assessment using user-independent classifiers of microcapillary electrophoresis traces. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanova, N., A. Sorokin, I. Anderson, N. Galleron, B. Candelon, V. Kapatral, A. Bhattacharyya, G. Reznik, N. Mikhailova, A. Lapidus, L. Chu, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, T. Walunas, Y. Grechkin, G. Pusch, R. Haselkorn, M. Fonstein, S. D. Ehrlich, R. Overbeek, and N. Kyrpides. 2003. Genome sequence of Bacillus cereus and comparative analysis with Bacillus anthracis. Nature 423:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotiranta, A., K. Lounatmaa, and M. Haapasalo. 2000. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bacillus cereus infections. Microb. Infect. 2:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lecadet, M., M. O. Blondel, and J. Ribier. 1980. Generalized transduction in Bacillus thuringiensis var. berliner 1715, using bacteriophage CP54 Ber. J. Gen. Microbiol. 121:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lereclus, D., H. Agaisse, M. Gominet, S. Salamitou, and V. Sanchis. 1996. Identification of a Bacillus thuringiensis gene that positively regulates transcription of the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C gene at the onset of the stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 178:2749-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindbäck, T., O. A. Økstad, A. L. Rishovd, and A. B. Kolstø. 1999. Insertional inactivation of hblC encoding the L2 component of Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 haemolysin BL strongly reduces enterotoxigenic activity, but not the haemolytic activity against human erythrocytes. Microbiology 145:3139-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lund, T., M.-L. DeBuyser, and P. E. Granum. 2000. A new cytotoxin from Bacillus cereus that may cause necrotic enteritis. Mol. Microbiol. 38:254-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahler, H., A. Pasa, J. Kramer, P. Schulte, A. Scoging, W. Bar, and S. Krahenbuhl. 1997. Fulminant liver failure in association with the emetic toxin of Bacillus cereus. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:1142-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miles, G., H. Bayley, and S. Cheley. 2002. Properties of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II: a heptameric transmembrane pore. Protein Sci. 11:1813-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller, J. M., J. G. Hair, M. Hebert, L. Hebert, F. J. Roberts, and R. S. Weyant. 1997. Fulminating bacteremia and pneumonia due to Bacillus cereus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:504-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyoshi, S. I., and S. Shinoda. 2000. Microbial metalloprotease and pathogenesis. Microb. Infect. 2:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moravek, M., R. Dietrich, C. Buerk, V. Broussolle, M. H. Guinebretiere, P. E. Granum, C. Nguyen-The, and E. Märtelbauer. 2006. Determination of the toxic potential of Bacillus cereus isolates by quantitative enterotoxin analyses. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 257:293-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mossel, D., M. Koopman, and E. Jongerius. 1967. Enumeration of Bacillus cereus in foods. Appl. Microbiol. 15:650-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ngamwongsatit, P., W. Buasri, P. Puianariyanon, C. Pulsrikarn, M. Ohba, A. Assavanig, and W. Panbangreb. 2008. Broad distribution of enterotoxin genes (hblCDA, nheABC, cytK, and entFM) among Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus as shown by novel primers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 121:352-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramarao, N., and D. Lereclus. 2005. The InhA1 metalloprotease allows spores of the B. cereus group to escape macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 7:1357-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ririe, K., R. P. Rasmussen, and C. T. Wittwer. 1997. Product differentiation by analysis of DNA melting curves during the polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 15:154-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowan, N. J., G. Caldow, C. G. Gemmell, and I. S. Hunter. 2003. Production of diarrheal enterotoxins and other potential virulence factors by veterinary isolates of Bacillus species associated with nongastrointestinal infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2372-2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salamitou, S., F. Ramisse, M. Brehélin, D. Bourguet, N. Gilois, M. Gominet, E. Hernandez, and D. Lereclus. 2000. The plcR regulon is involved in the opportunistic properties of Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus in mice and insects. Microbiology 146:2825-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siden, I., G. Dalhammar, B. Telander, H. G. Boman, and H. Somerville. 1979. Virulence factors in Bacillus thuringiensis: purification and properties of a protein inhibitor of immunity in insects. J. Gen. Microbiol. 114:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spira, W., and J. Goepfert. 1972. Bacillus cereus induced fluid accumulation in rabbit ileal loops. Appl. Microbiol. 24:341-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinthorsdottir, V., H. Halldorsson, and O. Andresson. 2000. Clostridium perfringens beta toxin forms multimeric transmembrane pores in human endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 28:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stenfors Arnesen, L., A. Fagerlund, and P. E. Granum. 2008. From soil to gut: Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:579-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reference deleted.

- 63.Vandesompele, J., K. De Preter, F. Pattyn, B. Poppe, N. Van Roy, A. De Paepe, and F. Speleman. 2002. Accurate normalization of real time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Gen. Biol. 3:RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]