Abstract

In contrast to normal differentiated cells, which rely primarily on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate the energy needed for cellular processes, most cancer cells instead rely on aerobic glycolysis, a phenomenon termed “the Warburg effect.” Aerobic glycolysis is an inefficient way to generate adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), however, and the advantage it confers to cancer cells has been unclear. Here we propose that the metabolism of cancer cells, and indeed all proliferating cells, is adapted to facilitate the uptake and incorporation of nutrients into the biomass (e.g., nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids) needed to produce a new cell. Supporting this idea are recent studies showing that (i) several signaling pathways implicated in cell proliferation also regulate metabolic pathways that incorporate nutrients into biomass; and that (ii) certain cancer-associated mutations enable cancer cells to acquire and metabolize nutrients in a manner conducive to proliferation rather than efficient ATP production. A better understanding of the mechanistic links between cellular metabolism and growth control may ultimately lead to better treatments for human cancer.

For unicellular organisms such as microbes, there is evolutionary pressure to reproduce as quickly as possible when nutrients are available. Their metabolic control systems have evolved to sense an adequate supply of nutrients and channel the requisite carbon, nitrogen, and free energy into generating the building blocks needed to produce a new cell. When nutrients are scarce, the cells cease biomass production and adapt metabolism to extract the maximum free energy from available resources to survive the starvation period (Fig. 1). Reflecting these fundamental differences in metabolic needs, distinct regulatory mechanisms have evolved to control cellular metabolism in proliferating versus non-proliferating cells.

Fig. 1.

Microbes and cells from multicellular organisms have similar metabolic phenotypes under similar environmental conditions. Unicellular organisms undergoing exponential growth often grow by fermentation of glucose into a small organic molecule such as ethanol. These organisms, and proliferating cells in a multicellular organism, both metabolize glucose primarily through glycolysis, excreting large amounts of carbon in the form of ethanol, lactate, or another organic acid such as acetate or butyrate. Unicellular organisms starved of nutrients rely primarily on oxidative metabolism, as do cells in a multicellular organism that are not stimulated to proliferate. This evolutionary conservation suggests that there is an advantage to oxidative metabolism during nutrient limitation and nonoxidative metabolism during cell proliferation.

In multicellular organisms, most cells are exposed to a constant supply of nutrients. Survival of the organism requires control systems that prevent aberrant individual cell proliferation when nutrient availability exceeds the levels needed to support cell division. Uncontrolled proliferation is prevented because mammalian cells do not normally take up nutrients from their environment unless stimulated to do so by growth factors. Cancer cells overcome this growth factor dependence by acquiring genetic mutations that functionally alter receptor-initiated signaling pathways. There is growing evidence that some of these pathways constitutively activate the uptake and metabolism of nutrients that both promote cell survival and fuel cell growth (1, 2). Oncogenic mutations can result in the uptake of nutrients, particularly glucose, that meet or exceed the bioenergetic demands of cell growth and proliferation. This realization has brought renewed attention to Otto Warburg’s observation in 1924 that cancer cells metabolize glucose in a manner that is distinct from that of cells in normal tissues (3, 4). By examining how Louis Pasteur’s observations regarding fermentation of glucose to ethanol might apply to mammalian tissues, Warburg found that unlike most normal tissues, cancer cells tend to “ferment” glucose into lactate even in the presence of sufficient oxygen to support mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. A definitive explanation for Warburg’s observation has remained elusive, at least in part because the energy requirements of cell proliferation appear at first glance to be better met by complete catabolism of glucose using mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to maximize adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) production.

In this review, we explore the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation in an attempt to understand why proliferating cells metabolize glucose by aerobic glycolysis. Knowledge of what proliferating cells need in terms of energy to generate biomass will help illuminate the connection between signaling pathways that drive cell growth and the regulation of cell metabolism.

Proliferating Mammalian Cells Exhibit Anabolic Metabolism

Our current understanding of metabolic pathways is based largely on studies of nonproliferating cells in differentiated tissues. In the presence of oxygen, most differentiated cells primarily metabolize glucose to carbon dioxide by oxidation of glycolytic pyruvate in the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This reaction produces NADH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), reduced], which then fuels oxidative phosphorylation to maximize ATP production, with minimal production of lactate (Fig. 2). It is only under anaerobic conditions that differentiated cells produce large amounts of lactate. In contrast, most cancer cells produce large amounts of lactate regardless of the availability of oxygen and hence their metabolism is often referred to as “aerobic glycolysis.” Warburg originally hypothesized that cancer cells develop a defect in mitochondria that leads to impaired aerobic respiration and a subsequent reliance on glycolytic metabolism (4). However, subsequent work showed that mitochondrial function is not impaired in most cancer cells (5–7), suggesting an alternative explanation for aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the differences between oxidative phosphorylation, anaerobic glycolysis, and aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect). In the presence of oxygen, nonproliferating (differentiated) tissues first metabolize glucose to pyruvate via glycolysis and then completely oxidize most of that pyruvate in the mitochondria to CO2 during the process of oxidative phosphorylation. Because oxygen is required as the final electron acceptor to completely oxidize the glucose, oxygen is essential for this process. When oxygen is limiting, cells can redirect the pyruvate generated by glycolysis away from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by generating lactate (anaerobic glycolysis). This generation of lactate during anaerobic glycolysis allows glycolysis to continue (by cycling NADH back to NAD+), but results in minimal ATP production when compared with oxidative phosphorylation. Warburg observed that cancer cells tend to convert most glucose to lactate regardless of whether oxygen is present (aerobic glycolysis). This property is shared by normal proliferative tissues. Mitochondria remain functional and some oxidative phosphorylation continues in both cancer cells and normal proliferating cells. Nevertheless, aerobic glycolysis is less efficient than oxidative phosphorylation for generating ATP. In proliferating cells, ~10% of the glucose is diverted into biosynthetic pathways upstream of pyruvate production.

Why Do Proliferating Cells Switch to a Less Efficient Metabolism?

As noted above, many unicellular organisms proliferate using fermentation, a microbial equivalent of aerobic glycolysis, and analogous to human cancer cells, preferentially ferment glucose even when oxygen is abundant (Fig. 1). This demonstrates that aerobic glycolytic metabolism can provide sufficient energy for cell proliferation. The metabolism of glucose to lactate generates only 2 ATPs per molecule of glucose, whereas oxidative phosphorylation generates up to 36 ATPs upon complete oxidation of one glucose molecule (8). This raises the question of why a less efficient metabolism, at least in terms of ATP production, would be selected for in proliferating cells.

One possible explanation is that inefficient ATP production is a problem only when resources are scarce. This is not the case for proliferating mammalian cells, which are exposed to a continual supply of glucose and other nutrients in circulating blood. Metabolic pathways and their regulation have only recently been studied in actively proliferating cells, and there is evidence that ATP may never be limiting in these cells. No matter how much they are stimulated to divide, cells using aerobic glycolysis also exhibit high ratios of ATP/ADP (adenosine 5′-diphosphate) and NADH/NAD+ (2, 9). Further, even minor perturbations in the ATP/ADP ratio can impair growth. Cells deficient in ATP often undergo apoptosis (10, 11). Normal proliferating cells can also undergo cell cycle arrest and reactivate catabolic metabolism when their ability to produce ATP from glucose is compromised (12, 13), and signaling pathways exist to sense energy status. The best characterized of these is initiated by the activity of adenylate kinases that buffer declining ATP production by converting two ADPs to one ATP and one AMP (adenosine 5′-monophosphate). This helps maintain a viable ATP/ADP ratio as ATP production declines, but the accumulation of AMP activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). This activation is dependent on the tumor suppressor protein LKB1 and leads to phosphorylation of several targets to improve energy charge in cells (14). LKB1 was initially identified as a tumor suppressor gene, suggesting that the ability to sense energy stress could be an important checkpoint to prevent malignant transformation in some cell types.

A second possible explanation for the switch to aerobic glycolysis, discussed in detail below, is that proliferating cells have important metabolic requirements that extend beyond ATP.

Crunching the Numbers–What Are the Metabolic Needs of Proliferating Cells?

To produce two viable daughter cells at mitosis, a proliferating cell must replicate all of its cellular contents. This imposes a large requirement for nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids. During growth, glucose is used to generate biomass as well as produce ATP. Although ATP hydrolysis provides free energy for some of the biochemical reactions responsible for replication of biomass, these reactions have additional requirements. For instance, synthesis of palmitate, a major constituent of cellular membranes, requires 7 molecules of ATP, 16 carbons from 8 molecules of acetyl-CoA (coenzyme A), and 28 electrons from 14 molecules of NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), reduced] (8). Likewise, synthesis of amino acids and nucleotides also consumes more equivalents of carbon and NADPH than of ATP. A glucose molecule can generate up to 36 ATPs, or 30 ATPs and 2 NADPHs [if diverted into the pentose phosphate shunt (8, 15)], or provide 6 carbons for macromolecular synthesis. Thus, to make a 16-carbon fatty acyl chain, a single glucose molecule can provide five times the ATP required, whereas 7 glucose molecules are needed to generate the NADPH required. This 35-fold asymmetry is only partially compensated by the consumption of 3 glucose molecules in acetyl-CoA production to satisfy the carbon requirement of the acyl chain itself. It is clear that for a cell to proliferate, the bulk of the glucose cannot be committed to carbon catabolism for ATP production. In addition, if this were the case, the resulting rise in the ATP/ADP ratio would severely impair the flux through glycolytic intermediates, limiting the production of the acetyl-CoA and NADPH required for macromolecular synthesis.

For most mammalian cells in culture, the only two molecules catabolized in appreciable quantities are glucose and glutamine. This means that glucose and glutamine supply most of the carbon, nitrogen, free energy, and reducing equivalents necessary to support cell growth and division. From this perspective, it becomes clear that converting all of the glucose to CO2 via oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria to maximize ATP production runs counter to the needs of a proliferating cell. Some glucose must be diverted to macromolecular precursors such as acetyl-CoA for fatty acids, glycolytic intermediates for nonessential amino acids, and ribose for nucleotides. This may explain at least part of the selective advantage provided by the Warburg effect, a hypothesis supported by recent 13C–nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurements showing that glioblastoma cells in culture convert as much as 90% of glucose and 60% of glutamine they acquire into lactate or alanine (16). Although most of this lactate and alanine is excreted from the cell as waste, one “byproduct” of their generation is a robust production of NADPH (Fig. 3). In addition to providing nitrogen for nonessential amino acids through transamination reactions, the catabolism of glutamine into lactate produces NADPH via the activity of NADP+-specific malate dehydrogenase (malic enzyme). Growth factor signaling also regulates the activity of the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase and modulates flux of carbon through the later steps of glycolysis (9, 17). This modulation of pyruvate kinase may facilitate the redirection of glucose metabolites into the pentose phosphate shunt, as well as nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis pathways. The conversion of both glucose and glutamine to lactate involves the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Inhibiting LDH activity impairs cell proliferation (6), possibly by interfering with the cell’s ability to excrete excess carbon. Elimination of excess carbon might be required to generate sufficient NADPH to support cell proliferation.

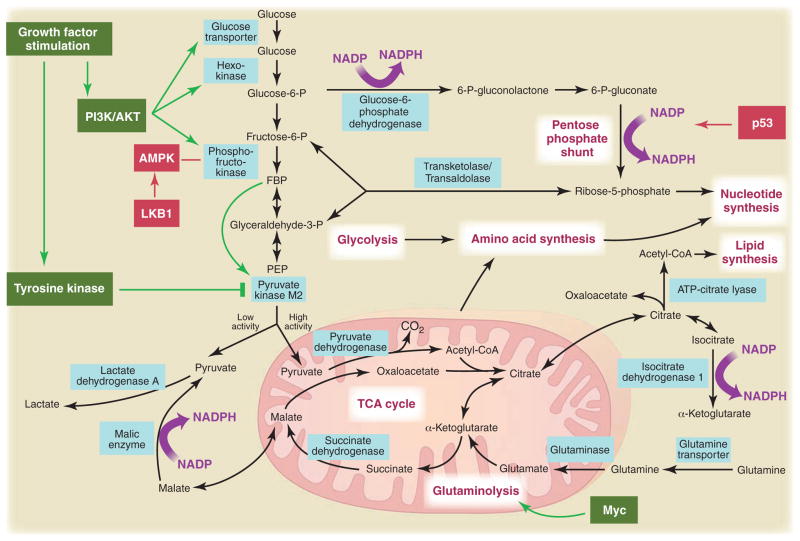

Fig. 3.

Metabolic pathways active in proliferating cells are directly controlled by signaling pathways involving known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. This schematic shows our current understanding of how glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, the pentose phosphate pathway, and glutamine metabolism are interconnected in proliferating cells. This metabolic wiring allows for both NADPH production and acetyl-CoA flux to the cytosol for lipid synthesis. Key steps in these metabolic pathways can be influenced by signaling pathways known to be important for cell proliferation. Activation of growth factor receptors leads to both tyrosine kinase signaling and PI3K activation. Via AKT, PI3K activation stimulates glucose uptake and flux through the early part of glycolysis. Tyrosine kinase signaling negatively regulates flux through the late steps of glycolysis, making glycolytic intermediates available for macromolecular synthesis as well as supporting NADPH production. Myc drives glutamine metabolism, which also supports NADPH production. LKB1/AMPK signaling and p53 decrease metabolic flux through glycolysis in response to cell stress. Decreased glycolytic flux in response to LKB/AMPK or p53 may be an adaptive response to shut off proliferative metabolism during periods of low energy availability or oxidative stress. Tumor suppressors are shown in red, and oncogenes are in green. Key metabolic pathways are labeled in purple with white boxes, and the enzymes controlling critical steps in these pathways are shown in blue. Some of these enzymes are candidates as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. Malic enzyme refers to NADP+-specific malate dehydrogenase [systematic name (S)-malate:NADP+ oxidoreductase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating)].

Most of the carbon for fatty acid synthesis is derived from glucose. During this process, glucose is first converted to acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrial matrix and used to synthesize citrate in the TCA cycle. Under conditions of high ATP/ADP and NADH/NAD+ exhibited by most proliferating cells, this citrate is excreted back into the cytosol where lipids are generated. In the cytosol, acetyl-CoA is recaptured from citrate and used as the carbon source for the growing acyl chains. Synthesis of acetyl-CoA from citrate requires the enzyme ATP citrate lyase (ACL), and disruption of ACL impairs tumor growth (18). Glutamine uptake also appears to be critical for lipid synthesis in that it supplies carbon in the form of mitochondrial oxaloacetate to maintain citrate production in the first step of the TCA cycle (16). Thus, metabolism of both glutamine and glucose is orchestrated to support the production of acetyl-CoA and NADPH needed for fatty acid synthesis. Flux of metabolites into other synthetic pathways for nucleic acid and amino acid synthesis must be similarly balanced.

The excess generation of lactate that accompanies the Warburg effect would appear to be an inefficient use of cellular resources. Each lactate excreted from the cell wastes three carbons that might otherwise be utilized for either ATP production or macromolecular precursor biosynthesis. Possibly the dumping of excess carbon as lactate is effective because it allows faster incorporation of carbon into biomass, which in turn facilitates rapid cell division. For most proliferating cells, nutrients are not limiting so there is no selective pressure to optimize metabolism for ATP yield. In contrast, a selective pressure for rate of metabolism does exist. Immune responses and wound repair depend on the speed of the proliferative expansion of effector cells. To survive, the organism must signal the responding cells to maximize their rate of anabolic growth. Cells that convert glucose and glutamine into biomass most efficiently will proliferate fastest. For the organism, nutrients may be scarce and there are pathways active in specialized, nonproliferating tissues to recycle the excess lactate and alanine dumped during the rapid cell growth of proliferating cells. The Cori cycle in the liver can recycle lactate generated from actively proliferating tissues to glucose, and analogous pathways exist to recycle the alanine generated from “inefficient” glutamine metabolism (8). This ability to recycle the organic waste produced by cell proliferation during an immune response or wound repair results in a minimal impact on the energy reserves of the whole organism. In addition, there is emerging evidence that cellular metabolism within a tumor can be heterogeneous, with some cells using the excess lactate generated as a fuel for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (19).

Metabolic Regulation Is a Component of the Cell Growth Machinery

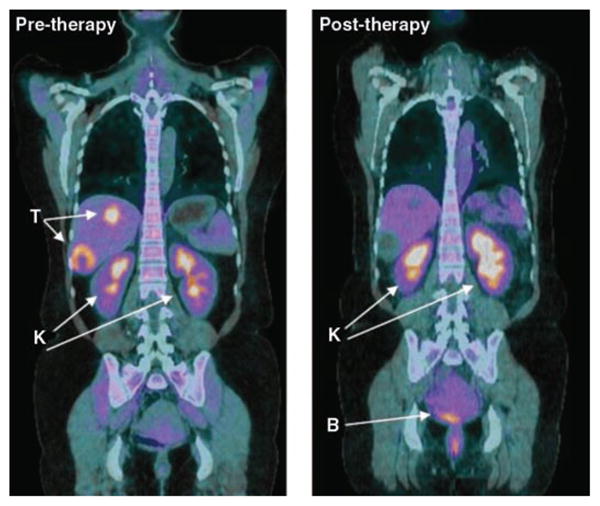

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway is linked to both growth control and glucose metabolism. In addition to a well-described role in directing available amino acids into protein synthesis via mTOR, the PI3K pathway regulates glucose uptake and utilization (Fig. 3). Even in non–insulin-dependent tissues, PI3K signaling through AKT can regulate glucose transporter expression, enhance glucose capture by hexokinase, and stimulate phosphofructokinase activity (2). PI3K pathway activation renders cells dependent on high levels of glucose flux (20). Small molecules that disrupt PI3K signaling lead to decreased glucose uptake by tumors as measured by 18F-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and the ability to inhibit tumor FDG uptake correlates with tumor regression (21). Glucose withdrawal induces cell death in a manner indistinguishable from that seen upon withdrawal of growth factor signaling, a phenomenon that may contribute to “oncogene addiction” (22). Indeed, where it has been examined in cancer patients, response to therapy is predicted by the ability to disrupt glucose metabolism as measured by FDG-PET (23) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Decreased metabolism of glucose by tumors, visualized by PET with the glucose analog FDG, predicts response to anticancer therapy. Shown are fused coronal images of FDG-PET and computerized tomography (CT) obtained on a hybrid PET/CT scanner after the infusion of FDG in a patient with a form of malignant sarcoma (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) before and after therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (sunitinib). The tumor (T) is readily visualized by FDG-PET/CT before therapy (left). After 4 weeks of therapy (right), the tumor shows no uptake of FDG despite persistent abnormalities on CT. Excess FDG is excreted in the urine, and therefore the kidneys (K) and bladder (B) are also visualized as labeled. [Image courtesy of A. D. Van den Abbeele, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston]

There is growing evidence that metabolic enzymes can directly contribute to carcinogenesis. Germline mutations in the TCA cycle enzymes succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase have been identified in some forms of human renal cell cancer, paraganglioma, and pheochromocytoma (24, 25). One effect of these mutations is activation of Hif1α-mediated glucose utilization (26). A recent analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain cancer, revealed that up to 12% of the tumors harbor the same point mutation in the gene encoding cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase–1 (IDH1) (27). Monoallelic mutation of the same residue in IDH1, or the analogous residue in the related enzyme IDH2, is a common feature of gliomas as more than 80% of indolent gliomas harbor such a mutation (28, 29). IDH1 and IDH2 couple the interconversion of cytosolic isocitrate and α-ketoglutarate in an NADP+/NADPH-dependent reaction. What effect this mutation has on cellular metabolism is not clear; however, given the important requirement for NADPH in macromolecular synthesis and redox control, alterations in NADPH production may affect cellular proliferation or mutation rates (30). Alternatively, such mutations may favor the production of citrate from α-ketoglutarate as a carbon precursor for macromolecular synthesis.

Many oncogenes are tyrosine kinases. One common feature of tyrosine kinase signaling associated with cell proliferation is regulation of glucose metabolism. In contrast to differentiated cells, proliferating cells selectively express the M2 isoform of the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase (PK-M2) (9). Unlike other pyruvate kinase isoforms, PK-M2 is regulated by tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins (17). Phosphotyrosine signaling downstream of a variety of cell growth signals shares the common ability to negatively regulate PK-M2 activity (17). In response to phosphotyrosine-protein binding, PK-M2 is induced into a low-activity state. This regulation of enzyme activity may constitute a molecular switch that allows cells to metabolize glucose through glycolysis in a manner that is consistent with proliferating cell metabolism only when growth signals are present (Fig. 3). Although counterintuitive, it is the low-activity form of PK-M2 that is necessary for cell proliferation. This regulation allows PK-M2 to act as a gatekeeper that dictates the flow of carbon into biosynthetic pathways versus complete catabolism for ATP production. In support of this idea, PK-M2 is required for proliferation in vivo (9).

Human tumor cells whose growth is driven by the MYC oncogene are particularly sensitive to glutamine withdrawal (31), and genes involved in glutamine metabolism appear to be under both the direct and indirect transcriptional control of the MYC protein (32, 33). Glutamine depletion from MYC-transformed cells results in the rapid loss of TCA cycle intermediates and cell death (31). Furthermore, this dependence on glutamine for survival is not related to the generation of ATP by glutamine metabolism.

Tumor suppressor pathways can also regulate cellular metabolism and may act to coordinate nutrient utilization with cell physiology. For instance, p53 expression controls metabolic genes and alters glucose utilization. Expression of TIGAR, a gene induced by p53, leads to inhibition of phosphofructokinase, redirection of glucose toward the pentose phosphate shunt, and NADPH production (34). This may be an adaptive response that protects the cell from oxidative stress, as NADPH is required to generate the reduced form of glutathione, which is a major intracellular defense against damage mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is the major cellular source of ROS production. Cells with excess nutrient uptake that have not converted to aerobic glycolysis would be predicted to have increased oxidative phosphorylation and ROS production. This maladaptive metabolic state may underlie the evolutionary selection for induction of apoptosis and/or senescence in the setting of increased ROS. Because some oncogenes drive glucose uptake, this hypothesis may explain oncogene-induced senescence. For instance, oncogenic Ras causes alterations in glucose metabolism (35) but causes senescence when expressed in cells without a cooperating oncogene (36). Further supporting this hypothesis is the observation that stationary-phase yeast lose viability when exposed to high levels of glucose and no additional nutrients (37). Yeast studies have also demonstrated that oxidative phosphorylation stops during S phase to limit ROS-mediated DNA damage, underscoring the importance of limiting oxidative phosphorylation and ROS production in proliferating cells (38).

What Triggers the Switch from Oxidative Phosphorylation to Aerobic Glycolysis?

One proposed explanation for Warburg’s observation is that tumor hypoxia selects for cells dependent on anaerobic metabolism (39). However, cancer cells appear to use glycolytic metabolism before exposure to hypoxic conditions. For example, leukemic cells are highly glycolytic (40, 41), yet these cells reside within the bloodstream at higher oxygen tensions than cells in most normal tissues. Similarly, lung tumors arising in the airways exhibit aerobic glycolysis even though these tumor cells are exposed to oxygen during tumorigenesis (9, 42). Thus, although tumor hypoxia is clearly important for other aspects of cancer biology, the available evidence suggests that it is a late-occurring event that may not be a major contributor in the switch to aerobic glycolysis by cancer cells.

The classic view of metabolism is that of a self-correcting, homeostatic system where a core set of housekeeping enzymes enables the cell to respond to changing bioenergetic demands. However, as described above, the evolving evidence instead points to a dynamically regulated system that is programmed to fit the requirements for cell proliferation or meet the specific needs of each differentiated tissue as appropriate. For normal proliferating tissues, such as in the developing embryo or during an immune response in the adult, signals from growth factors allow cells to utilize nutrients for growth (41, 43). Perhaps one function of oncogenic pathways is to drive cell-autonomous nutrient uptake and program proliferative metabolism, whereas one function of tumor suppressor pathways is to prevent nutrient utilization for anabolic processes. In this model, for cancer to arise, mutations are needed to give cells the ability to acquire nutrients and coordinately regulate metabolic pathways to support proliferation. This alteration in metabolic control may result by reverting to an embryonic program, or evolving the capability to alter existing cell metabolism in a way that supports cell growth.

Cellular Metabolism and Human Cancer

In principle, the metabolic dependencies of cancer cells can be exploited for cancer treatment. For instance, a large fraction of human cancer is dependent on aberrant signaling through the PI3K/Akt pathway, and agents that target PI3K and various downstream signaling molecules are now in clinical trials. The growing evidence that activation of PI3K causes increased dependency on glycolysis suggests that these agents may exert some of their effect by disrupting glucose metabolism. Drugs targeting key metabolic control points important for aerobic glycolysis, such as PK-M2 or LDH-A, might also warrant investigation as potential cancer therapies. In addition, the drugs developed to target metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes may have use in treating cancer. A number of retrospective clinical studies have found that the widely used diabetes drug metformin may offer a possible benefit in cancer prevention as well as improved outcomes when used with other cancer therapies (44). Metformin and the more potent related compound Phenformin activate AMPK in cells, suggesting that Phenformin or other activators of AMPK might also be used as an adjunct to cancer therapy. Optimal use of these drugs will require a better understanding of cancer cell metabolism and identification of the signaling pathways that represent an Achilles’ heel for cell proliferation or survival.

Metabolic tissues in mammals transform ingested food into a near-constant supply of glucose, glutamine, and lipids to balance the metabolic needs of both differentiated and proliferating tissues. Alterations in the appropriate balance of fuels and/or signal transduction pathways that deal with nutrient utilization may underlie the cancer predisposition associated with metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity (45, 46). A better understanding of how whole-body metabolism interacts with tumor metabolism may better define these risks and identify potential points of therapeutic intervention. In addition, it is possible that the cachexia associated with many cancers is exacerbated by the excess nutrient consumption by the tumor, which would affect whole-body metabolic regulation. To this end, the potential role of dietary supplements and tight glucose control as adjuncts to cancer treatment is an active field of investigation.

Future Prospects

Metabolism is involved directly or indirectly in essentially everything a cell does. There is mounting evidence for cross-talk between signaling pathways and metabolic control in every multicellular organism studied. There is still much to learn about how proliferating cell metabolism is regulated. Despite a long and rich history of research, the complex connection between metabolism and proliferation remains an exciting area of investigation. Indeed, new metabolic pathways have been discovered as recently as the 1980s (47), and it is possible that additional pathways have yet to be described. Understanding this important aspect of biology is likely to have a major impact on our understanding of cell proliferation control and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Van den Abbeele (Department of Imaging, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston) for the FDG-PET image. We also thank K. D. Courtney, A. J. Shaywitz, and K. D. Swanson for thoughtful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation for support (to M.G.V.H.). M.G.V.H. receives grant support from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and NIH; L.C.C. receives grant support from the NIH; and C.B.T. receives grant support from the NCI, NIH, and Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute to study aspects of cancer cell metabolism. M.G.V.H., L.C.C., and C.B.T. hold patents related to the targeting of cancer cell metabolism and have financial interests in Agios Pharmaceuticals, a company that seeks to exploit alterations in cancer metabolism for novel therapeutics.

References and Notes

- 1.Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cell. 2008;134:703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deberardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O, Posener K, Negelein E. Biochem Z. 1924;152:319. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. Science. 1956;123:309. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinhouse S. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1976;87:115. doi: 10.1007/BF00284370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fantin VR, St-Pierre J, Leder P. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:425. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno-Sanchez R, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Marin-Hernandez A, Saavedra E. FEBS J. 2007;274:1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehninger AL, Nelson DL, Cox MM. Principles of Biochemistry. 2. Worth; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christofk HR, et al. Nature. 2008;452:230. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izyumov DS, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1658:141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Mol Cell. 1999;3:159. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw RJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lum JJ, et al. Cell. 2005;120:237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardie DG. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:774. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Possibly up to four NADPH molecules per glucose can be produced if the products of the pentose phosphate shunt are metabolized via the TCA cycle and malic enzyme or cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) to generate two additional NADPH molecules.

- 16.DeBerardinis RJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Nature. 2008;452:181. doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzivassiliou G, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonveaux P, et al. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3930. doi: 10.1172/JCI36843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buzzai M, et al. Oncogene. 2005;24:4165. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelman JA, et al. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vander Heiden MG, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5899-5912.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Haim S, Ell P. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:88. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baysal BE, et al. Science. 2000;287:848. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollard PJ, Wortham NC, Tomlinson IP. Ann Med. 2003;35:634. doi: 10.1080/07853890310018458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selak MA, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:77. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons DW, et al. Science. 2008;321:1807. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleeker FE, et al. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:7. doi: 10.1002/humu.20927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan H, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson CB. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0810213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuneva M, Zamboni N, Oefner P, Sachidanandam R, Lazebnik Y. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wise DR, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao P, et al. Nature. 2009;458:762. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensaad K, et al. Cell. 2006;126:107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiaradonna F, et al. Oncogene. 2006;25:5391. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Cell. 1997;88:593. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granot D, Snyder M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Z, Odstrcil EA, Tu BP, McKnight SL. Science. 2007;316:1916. doi: 10.1126/science.1140958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottschalk S, Anderson N, Hainz C, Eckhardt SG, Serkova NJ. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6661. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elstrom RL, et al. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nolop KB, et al. Cancer. 1987;60:2682. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871201)60:11<2682::aid-cncr2820601118>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondoh H, et al. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:293. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. BMJ. 2005;330:1304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollak M. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Maghrabi MR, Pilkis SJ. J Cell Biochem. 1984;26:1. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240260102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]