Abstract

Recent studies suggest that human neuropeptide Y (NPY) plays a prominent role in management of stress response and emotion, and higher NPY levels observed in combat-exposed veterans may help coping with posttraumatic stress. Neuropeptide F (NPF), the counterpart of NPY in Drosophila melanogaster, also displays parallel activities, including promotion of resilience to diverse stressors and prevention of uncontrolled aggressive behavior. However, it remains unclear how NPY family peptides modulate physical and emotional responses to various stressors. Here we show that NPFR1, a G-protein-coupled NPF receptor, exerts an inhibitory effect on larval aversion to diverse stressful stimuli mediated by different subtypes of fly and mammalian transient receptor potential (TRP) family channels. Imaging analysis in larval sensory neurons and cultured human cells showed that NPFR1 attenuates Ca2+ influx mediated by fly TRPA and rat TRPV1 channels. Our findings suggest that suppression of TRP channel-mediated neural excitation by the conserved NPF/NPFR1 system may be a major mechanism for attaining its broad anti-stress function.

Introduction

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) family peptides, which are widely conserved among metazoans, have been implicated in stress and pain response (Bannon et al., 2000; Thorsell et al., 2000; Thorsell and Heilig, 2002; Wu et al., 2005a,b). Recent studies suggest that individuals with haplotypes of low NPY expression levels are more prone to develop pain and stress disorders (Zhou et al., 2008). Neuropeptide F (NPF) is an abundant signaling peptide in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster feeding larvae. The NPF system appears to be a central regulator of stress response (Wu et al., 2003, 2005a,b). In food-deprived larvae, NPF signaling is responsible for resistance to diverse stressors, enabling animals to engage in hunger-driven behaviors such as risk-prone food acquisition and motivated procurement of hard food media. Moreover, increased NPF signaling in fed animals selectively elicits stress-resistant seeking behaviors but not food ingestion per se, suggesting that the NPF pathway promotes foraging motivation in hungry animals through an uncharacterized anti-stress mechanism.

The transient receptor potential (TRP) family cation channels are evolutionarily conserved sensors of diverse stressful stimuli (Montell et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2004; Montell, 2005; Ramsey et al., 2006). Mammalian TRPV1 is a polymodal channel protein that responds to noxious heat, protons, and capsaicin (Caterina et al., 1997; Caterina and Julius, 2001). TRPV1 activity is regulated by multiple signaling pathways. For example, endogenous pain suppressors such as opioid peptides and endocannabinoids attenuate TRPV1-mediated external noxious stimulation through their G-protein-coupled receptors expressed in peripheral nociceptors (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2002; Díaz-Laviada and Ruiz-Llorente, 2005; Endres-Becker et al., 2007). Conversely, TRPV1 activity can also be sensitized by diverse signaling molecules and kinase-mediated pathways, many of which are responsible for inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Hucho et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2007; Mostany et al., 2008).

Drosophila TRPA channel protein PAINLESS (PAIN) is required for fly aversive response to thermal, mechanical, and chemical stressors (Tracey et al., 2003; Al-Anzi et al., 2006). PAIN also plays a developmental role in the behavioral switch of postfeeding larvae from sugar attraction to aversion. The PAIN-mediated sugar aversion drives postfeeding larvae out of the aquatic feeding habitat to food-free sites (e.g., from fallen overripe fruits to soil underneath), thereby preventing immobile pupae from microbial killing and drowning in liquid food (Chiang, 1950; Ashburner, 1989). However, the PAIN-mediated neuronal pathway for sugar avoidance must be suppressed in younger feeding larvae that live mostly inside sugar-rich food proper. We have shown that fly NPY-like brain peptide NPF suppresses PAIN-mediated sugar aversion throughout early larval development; loss of NPF signaling in feeding larvae is sufficient to trigger precocious sugar-averse behaviors (Wu et al., 2003). In this work, we use the Drosophila larva as a model to investigate the activities of NPF and its G-protein-coupled receptor (NPFR1) in suppression of TRP channel activities and associated behaviors. Our findings suggest that the conserved NPF signaling system is capable of suppressing TRP channel-mediated responses to diverse stressful stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Flies, media, and larval growth.

Conditions for rearing adult flies and egg collection were described previously (Shen and Cai, 2001; Wen et al., 2005). The larvae were raised at 25°C with exposure to natural lighting. Synchronized eggs were collected within a 2 h interval, and late second instars were transferred to a fresh apple juice plate with yeast paste (<80 larvae per plate). The pain–gal4, UAS–TRPV1, UAS–npfr1cDNA, UAS–npfr1dsRNA, UAS–npf, UAS–G-CaMP, UAS–PKAi, and UAS–PKAc lines are in the w background (Kiger et al., 1999; Tracey et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2005; Marella et al., 2006; Gordon and Scott, 2009).

Behavioral assays.

The migration assay on soft agar media was performed as described previously (Xu et al., 2008). Twenty-five postfeeding larvae [96 h after egg laying (AEL)] in one plate were allowed to move freely on the medium, and those that crawled onto the plastic surface became less mobile and eventually formed pupae there. The percentage of pupae on agar media was scored after 24 h. The clumping assay was also described previously (Wu et al., 2003). Briefly, 45 mm Petri dishes containing solid fructose agar (3% agar in a 10% fructose solution) were coated with a thin layer of yeast paste (0.5 g of yeast powder in 10% fructose solution). Thirty larvae per plate were allowed to browse for 30 min, and those in clumps were scored immediately. The social burrowing assay was performed on solid agar media containing apple juice or 10% fructose, as described previously (Wu et al., 2003). All assays, unless stated otherwise, were performed at room temperature in the dark. At least three separate trials were performed per assay.

The thermonociception assay was performed according to previously published procedures with modifications (Tracey et al., 2003). The temperature of the electric heating probe was set at 40°C using a variable transformer (model 72-110; Tenma) and monitored by a digital thermometer (model 52 II; Fluke). At least 150 larvae (96 h AEL) were individually tested for each line.

The two-choice preference test was based on a published procedure with some modifications (Al-Anzi et al., 2006). Two-day-old males withheld from food for 24 h were presented with a 48-well plate containing two-colored food media in the alternating well rows. They contain 1% agar/10% fructose with 0.4 mm benzyl-isothiocyanate (BITC) in 75% ethanol or ethanol only. In each assay, 90–100 flies per line were tested in the dark. A preference index was defined as the fraction of larvae choosing the BITC medium, minus the fraction of larvae choosing the BITC-free medium. A preference index close to +1 indicates that the larvae are attracted to BITC, whereas −1 indicates strong rejection. At least three trials were done for each line.

Immunohistochemistry.

Larval epidermis was filleted from the dorsal side. Tissues were fixed for 35 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100. Tissues were blocked in 5% normal donkey serum and then incubated overnight at 4°C with affinity-purified rabbit anti-NPFR1 antibodies (1:100) and mouse anti-green fluorescent protein antibodies (1:1000). The NPFR1 peptide antibodies were raised and purified using two peptide antigens (CMTGHHEGGLRSAIT and SSNSVRYLDDRHPLC). Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and Alexa 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were diluted 1:2000. After secondary antibody incubation, tissues were dehydrated in ethanol series and 100% xylene before mounting. At least 16 epidermal tissues were examined for each genotype.

In vivo calcium imaging.

Detailed procedures for calcium imaging of sensory neurons using yellow chameleon 2.1 (YC2.1) and SOARS (statistical optimization for the analysis of ratiometric signals) analysis were described previously (Xu et al., 2008). The SOARS method extracts the anticorrelated change of Fluo-4 and Fura-red signals in a cell (represented by a cluster of ∼100 pixels) that respond to stimulations in a common dynamic pattern. At least six epidermal tissues were imaged for each group. To quantify the significance of anticorrelated fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) response to fructose stimulation, we calculated p values for a periodic (sinusoidal) response at the stimulus frequency using multitaper harmonic analysis, a common method for the detection of sinusoids in noisy data (Thomson, 1982). In vitro calcium imaging experiments using G-CaMP (Gordon and Scott, 2009) were performed following the same protocols as those with YC2.1. Larva fillets were incubated in HL6–lactose solution (NPF-free or containing 1 μm NPF) for ∼40 min, followed by fructose stimulation and Ca2+ imaging. The tissues were washed with NPF-free HL6–lactose solution for 30 min and imaged again using the same stimulation paradigm described above. The time series confocal images were analyzed in NIH ImageJ. The fluorescence profile of an individual neuron was generated using the ROI function in NIH ImageJ.

Transfection and calcium imaging of HEK293 cells.

Human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were maintained under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) in DMEM (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. pcDNA3.1D directional expression system (Invitrogen) was used to clone and express rat TRPV1 and fly NPFR1 cDNA in HEK293 cells. TRPV1 cDNA was PCR amplified from TRPV1 (E600K) sequence (Marella et al., 2006), using the following primers: 5′ CACCATGGAAC AACGGGCTAGCTTA 3′ and 5′ TTCTTTCTCCCCTGGGACCA TGGA 3′. NPFR1 cDNA was PCR amplified from an NPFR1 cDNA plasmid(34), using two primers: 5′ CACCATGATAATCAGCATGAATCAGA3′ and 5′TTACCGCGGCATCAGCTTG GT3′. HEK293 cells were cultured on eight-well polyornithine-coated chambered cover glasses (Nunc) for 24 h before transfection. A suspension of 200 μl of water containing 0.4 μg of plasmid DNA and 0.8 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for transfection. The amounts of TRPV1 and NPFR1 cDNA used were 20 and 200 ng, respectively. pcDNA3.1 vector DNA was supplemented, when necessary, to ensure the equal amount of total DNA per transfection.

Calcium imaging was performed between 36 and 42 h after transfection at 23°C. Cells were loaded with 1 μm Fluo-4 and 2 μm Fura-red (Invitrogen) for 90 min in HBSS (Invitrogen), washed once with HBSS, and imaged using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200M scope equipped with a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 Meta laser scanning module. Dyes were excited at 488 nm with argon laser. Emission fluorescence was filtered by a bandpass 505–530 filter and a long-pass 585 filter. Images were collected for 300 s during capsaicin stimulation at 1 frame/s and analyzed with the SOARS analysis. The p values were calculated using Student's t test for changes in the fluorescence ratio of Fluo-4 over Fura-red within 5 s intervals sampled from the 50 s recording period (starting at t = 150 s). The differences between experimental and control traces are statistically significant (p < 0.026). NPF was chemically synthesized by Quality Controlled Biochemicals. NPF and cyclic nucleotide analogs (Sigma) were preincubated at 23°C with cells for 20–25 min before adding capsaicin.

Results

NPFR1 suppression of peripheral aversive stimulation

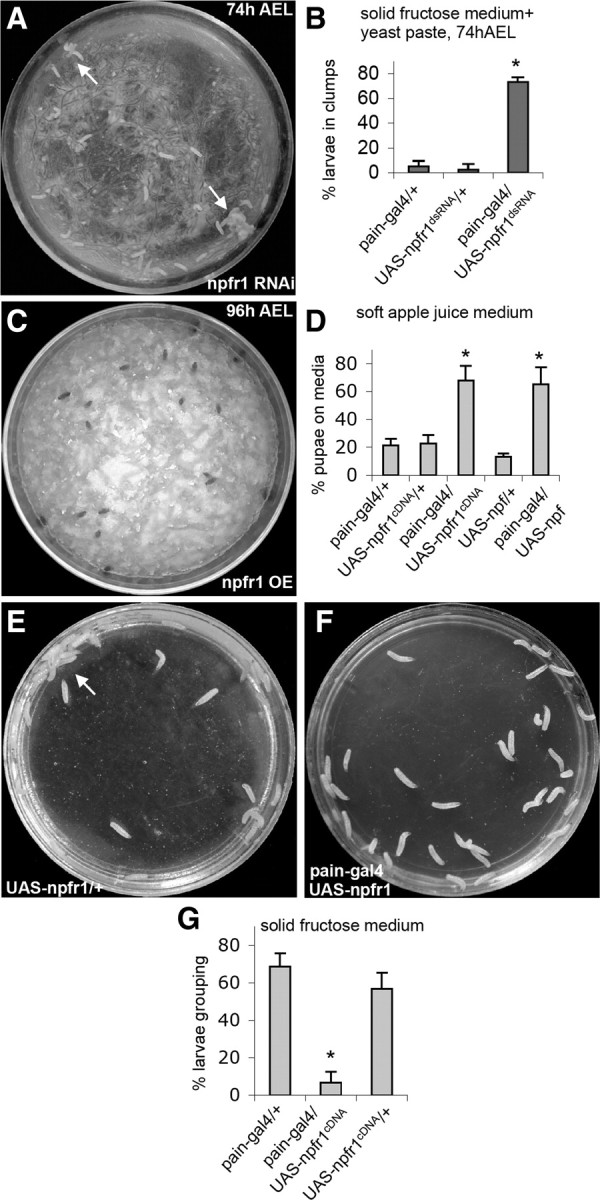

The G-protein-coupled NPF receptor NPFR1 is expressed in a subset of sugar-responsive PAIN neurons in the thoracic body but is absent from other peripheral PAIN neurons (Xu et al., 2008). We postulate that such restricted NPFR1 expression pattern may enable the NPF/NPFR1 system to selectively block PAIN-mediated neuronal excitation by aversive sugar in younger feeding larvae (in which brain NPF is high) without interfering with the nociceptive activities of PAIN in other sensory neurons. To test this hypothesis, we first examined whether knockdown of npfr1 activity with RNA interference could derepress sugar-elicited activation of PAIN channels and cause premature onset of sugar-averse behaviors in feeding larvae (74 h AEL). Indeed, we found that expression of npfr1 double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) driven by pain–gal4 triggered precocious onset of sugar-elicited grouping behavior normally associated with older postfeeding larvae (Fig. 1A,B;), phenocopying NPF signaling-deficient larvae (Wu et al., 2003). Second, we observed opposite behavioral phenotypes when an npfr1 cDNA was overexpressed in postfeeding larvae (96 h AEL). In soft apple juice agar media, wild-type postfeeding larvae normally migrate out of the food medium (Xu et al., 2008). As expected, a majority of control larvae (e.g., UAS–npfr1cDNA alone) moved out of the medium, whereas ∼60% of NPFR1-overexpressing larvae (pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1cDNA) (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) remained (Fig. 1C,D). Moreover, postfeeding larvae expressing NPF (pain–gal4/UAS–npf) (supplemental Fig. S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) also showed attenuated food aversion. Thus, increased NPF or NPFR1 activity dominantly suppresses larval food-averse migration.

Figure 1.

Regulation of sugar-stimulated social response by decreased or increased NPFR1 signaling. A, UAS–npfr1dsRNA encodes an npfr1 double-stranded RNA. Young control larvae (74 h AEL) disperse randomly on solid fructose agar coated with a thin layer of 10% fructose yeast paste. However, at least 70% of younger experimental larvae (pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1dsRNA, 74 h AEL) behaved like older postfeeding larvae, displaying stable aggregation at the edge of the plate (arrows) (Wu et al., 2003). B, Quantification of the larval clumping activities. p < 0.001. C, UAS–npfr1cDNA and UAS–npf contain an npfr1 and npf coding sequence, respectively. Most postfeeding larvae overexpressing NPFR1 in PAIN neurons pupated on apple juice agar paste, whereas control larvae migrated out of the food medium to pupate on food-free surface. OE, Overexpressing. D, Quantification of the larval migratory activities. p < 0.001. E, Postfeeding control larvae (e.g., UAS–npfr1cDNA/+, 96 h AEL) normally show a sequential display of dispersing, clumping, and cooperative burrowing on the solid 10% fructose agar medium within a 30 min period. The arrow indicates a cooperative burrowing site. Pictures were taken 30 min after the larvae were transferred onto the medium. F, Postfeeding larvae overexpressing NPFR1 in PAIN neurons showed no clumping or burrowing activity on 10% fructose agar medium even after 1.5 h. G, Quantification of the larval clumping activities. p < 0.001. In all figures, unless otherwise stated, error bars represent SDs. At least three separate trials were performed for each experiment. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from paired controls using ANOVA, followed by Student–Newman–Keuls analysis.

When exposed to hard sugar-containing media, postfeeding larvae (96 h AEL), but not feeding larvae, rapidly swarm toward each other and form stable aggregates (Wu et al., 2003). This instinctive cooperative behavior may enable larvae to quickly burrow through sugar-containing hard media (e.g., fruit juice-stained compact surface soil) for pupation (Thomas, 1995; Alyokhin et al., 2001). We also found that pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1cDNA postfeeding larvae failed to display aggregation and burrowing on the 10% fructose agar medium (Fig. 1E–G). Together, these findings suggest that the G-protein-coupled NPF receptor NPFR1 negatively regulates PAIN-mediated larval food-averse behaviors.

NPF/NPFR1 suppression of TRPA channel-mediated Ca2+ influx

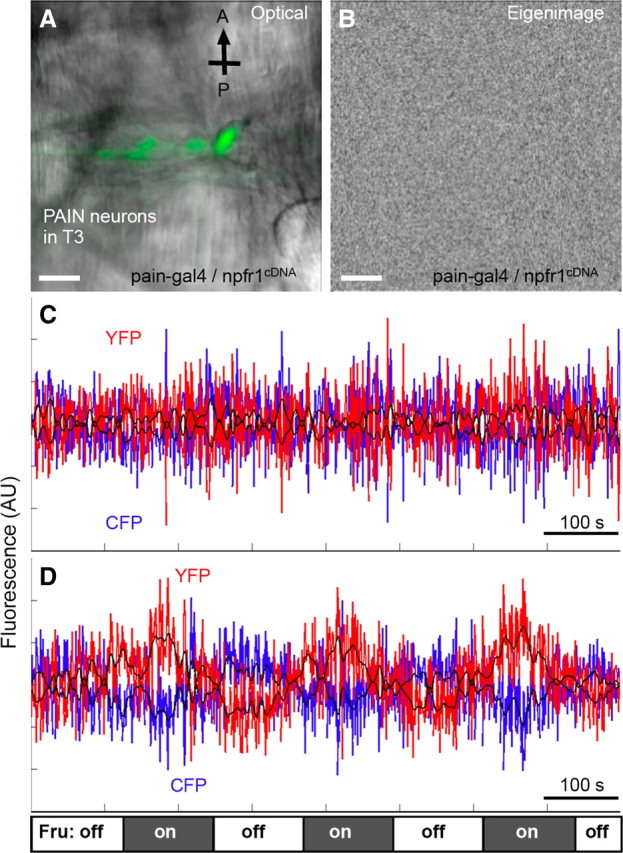

We also performed cellular imaging analysis to examine how NPFR1 might affect the activity of TRP family channels in sugar-responsive PAIN neurons with a Ca2+ indicator, YC2.1 (Miyawaki et al., 1999). The thoracic PAIN neurons of 96 h AEL postfeeding larvae were imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy and subsequently processed using the SOARS algorithm, which is designed to extract the anticorrelated changes between yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fluorescence levels in response to fructose stimulation (Broder et al., 2007). We found that, similar to the situation in pain3 larvae (96 h AEL), fructose failed to trigger excitation of the thoracic PAIN neurons in pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1cDNA larvae (96 h AEL) (Fig. 2) (Xu et al., 2008). This finding suggests that NPFR1 may function as a potent inhibitor of the activities of TRP channels.

Figure 2.

Imaging and SOARS analysis of excitation of thoracic PAIN neurons by fructose with the chameleon Ca2+ indicator. Stimulation paradigm: the tissue was initially perfused with HL6–lactose solution for up to 10 min before imaging. During imaging, solutions were changed every 120 s, alternating between HL6–lactose and HL6–fructose. At least six tissues per group were imaged. Scale bars, 20 μm. A, A composite fluorescent and transmitted light image of pain-expressing neurons from the ventral left cluster in the third thoracic segment of the NPFR1-overexpressing larva (pain–gal4, UAS–npfr1cDNA; UAS–YC2.1). CFP fluorescence is shown in green. A, Anterior; P, posterior. B, An eigen image of the above tissue generated from the SOARS analysis of the chameleon YFP/CFP FRET data. This eigen image facilitates the identification of pixels that may display spatially correlated, temporally anticorrelated fluorescence changes selectively responding to fructose stimulation (Xu et al., 2008). No spatial-correlated pixels were detected. C, The time course of the weighted mask in the datasets shows no periodic anticorrelated changes of the CFP and YFP signals (blue and red traces, respectively; p > 0.1, multitaper harmonic analysis). D, Imaging and data analysis of the same set of thoracic pain-expressing neurons from control larvae (pain–gal4; UAS–YC2.1) that display periodic anticorrelated changes of the CFP and YFP signals under the same conditions as described above (p < 0.0001). The fructose stimulation paradigm is indicated at the bottom (FRU). Three complete cycles of solution alternation are shown here. AU, Arbitrary units.

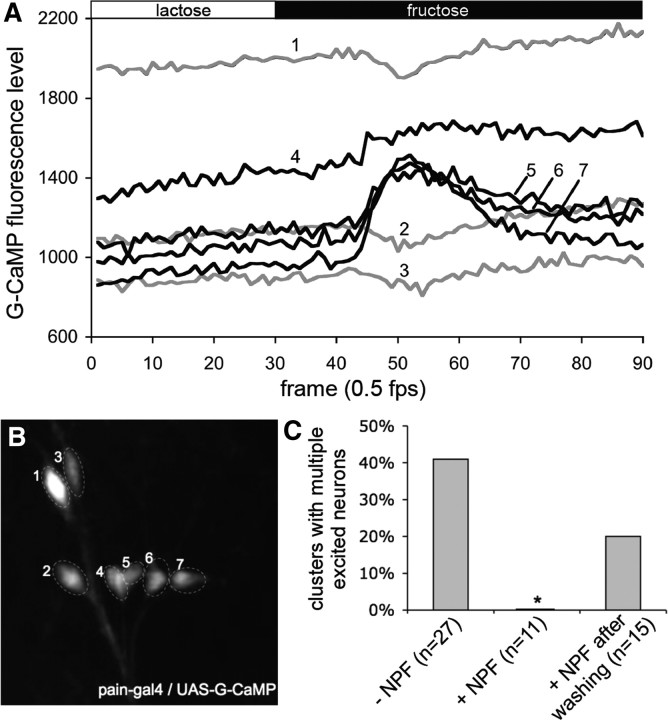

To provide functional evidence that direct activation of NPFR1 by NPF is responsible for the suppression of sugar excitation of thoracic PAIN neurons, we performed calcium imaging analysis of tissues from postfeeding larvae (96 h AEL) in the presence of 1 μm NPF (Garczynski et al., 2002). In this set of experiments, we used another Ca2+ indicator, G-CaMP, which provides more sensitive detection of changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels (Wang et al., 2003). In the absence of NPF, sugar elicited intracellular Ca2+ increases in multiple neurons from at least 40% of clusters of NPFR1-positive PAIN neurons in the thoracic segments (Fig. 3). In contrast, larval tissues perfused with NPF displayed no such responses, which can, however, be restored by rinsing tissues with the NPF-free imaging medium. These findings suggest that upregulation of the NPF system by increasing either NPF or NPFR1 activity leads to suppression of PAIN-mediated food aversion in postfeeding larvae.

Figure 3.

NPF suppression of sugar excitation of NPFR1-positve PAIN neurons from postfeeding larvae. Stimulation paradigm: the tissue was initially perfused with HL6–lactose solution for 5 min before imaging. Each tissue was imaged in HL6–lactose for 60 s and then in HL6–fructose for 120 s. A, Representative traces showing G-CaMP fluorescence changes of thoracic PAIN neurons of normal postfeeding larvae (96 h AEL) in response to fructose. The numbers on the traces correspond to the labeled neurons in B. B, G-CaMP labeled PAIN neurons in the second thoracic segment. C, Quantification of the NPF inhibitory effect on sugar excitation of thoracic clusters of PAIN neurons. Perfusion of larval tissues with 1 μm NPF significantly attenuated the number of G-cAMP-expressing PAIN neurons excitable by fructose.

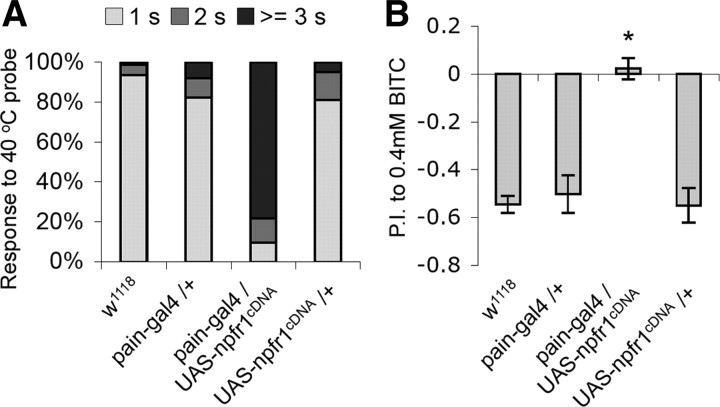

NPFR1 suppression of TRPA channel-mediated nociception

In pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1cDNA larvae, NPFR1 is ectopically expressed in the entire set of PAIN neurons, including those that are responsive to noxious heat (Tracey et al., 2003). Because the NPF/NPFR1 system potently suppresses PAIN channel activity, we decided to test whether NPFR1 may also affect PAIN-mediated noxious heat response of those larvae. We found that pain–gal4/UAS–npfr1cDNA larvae showed significantly delayed aversive response to the touch of a 40°C probe (Fig. 4A). In addition, the PAIN-mediated response to BITC, the pungent ingredient of horseradish, was also abolished by NPFR1 overexpression in adult PAIN neurons (Fig. 4B) (Al-Anzi et al., 2006). These results demonstrate that NPFR1 is capable of suppressing fly sensory responses to various chemical stressors and noxious heat mediated by nociceptive TRPA channels.

Figure 4.

NPFR1 suppresses PAINLESS-mediated thermal nociception in larvae and chemical nociception in adults. A, NPFR1 suppresses PAINLESS-mediated thermal nociception in larvae. Most wild-type larvae display a stereotypical rolling behavior within 1 s when touched by a 40°C probe to the lateral body wall (Tracey et al., 2003). In contrast, the majority of NPFR1 overexpressors respond after 3 s. n > 100 for each line tested. B, NPFR1 suppresses PAIN neuron-mediated chemical nociception in adults. Two-day old control flies mostly avoided 0.4 mm BITC. However, the NPFR1 overexpressing flies showed no preference to either of the two types of food. n > 250 for each line tested.

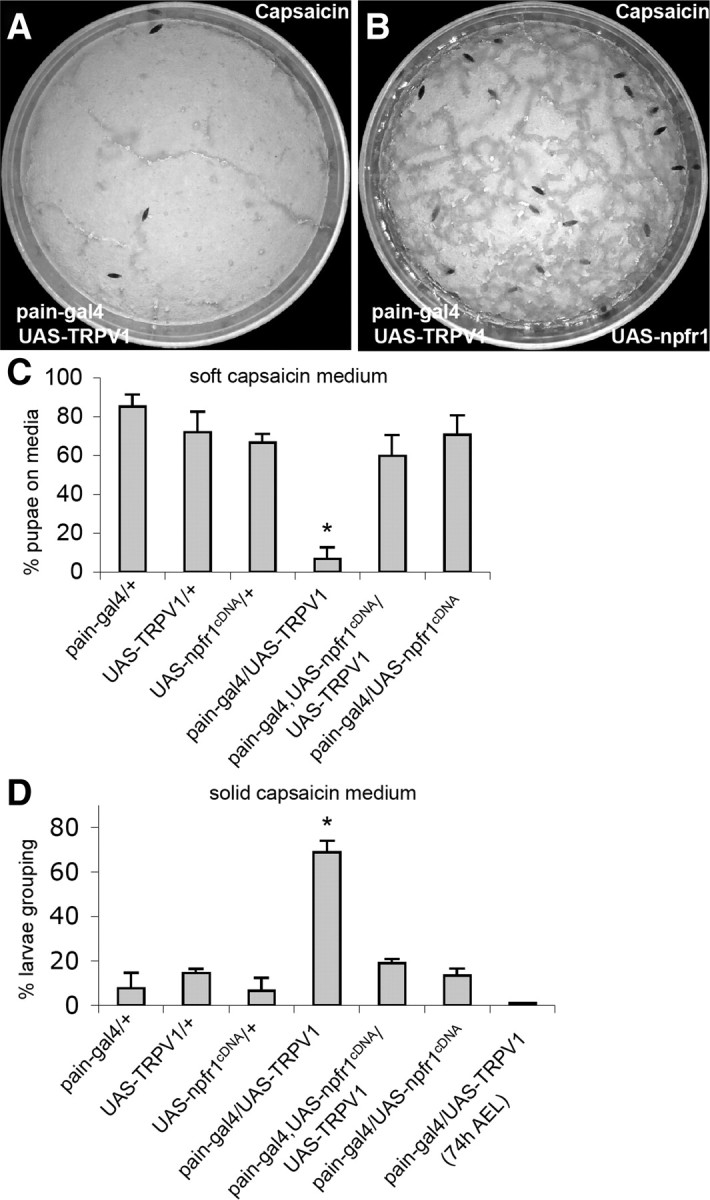

Suppression of mammalian TRPV1-mediated avoidance by NPFR1

Wild-type Drosophila larvae display neither attractive nor aversive response to capsaicin, the spicy substance from hot chili peppers. However, expression of a rat capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in PAIN neurons of postfeeding larvae is sufficient to trigger larval aversion to capsaicin (Xu et al., 2008). This finding provides an opportunity to test whether NPFR1 is capable of suppressing a mammalian nociceptive TRP channel of a different subtype in Drosophila sensory neurons. We found that postfeeding larvae coexpressing NPFR1 and TRPV1, driven by pain–gal4, failed to display capsaicin-averse behaviors (Fig. 5). Consistent with this finding, younger feeding larvae expressing rat TRPV1 are also insensitive to capsaicin (Xu et al., 2008). These results suggest that NPFR1 signaling is capable of suppressing sensory response to diverse forms of stressors mediated by different subtypes of TRP channels, and its antinociceptive activity may be mediated by a signaling mechanism conserved between flies and mammals.

Figure 5.

NPFR1 suppresses larval avoidance to capsaicin induced by ectopically expressed mammalian TRPV1. UAS–TRPV1 encodes a variant of the mammalian vanilloid receptor TRPV1 (TRPV1E600K). A, Control larvae expressing UAS–TRPV1 driven by pain–gal4 migrate away from agar paste containing 400 nm capsaicin. B, Experimental larvae expressing both NPFR1 and TRPV1 in PAIN cells mostly remained on the capsaicin medium. C, Quantification of avoidance response of transgenic larvae in media containing capsaicin. p < 0.001. D, Quantification of capsaicin-induced larval aggregation on the sugar-free capsaicin medium. Larvae expressing TRPV1 alone (pain–gal4/UAS–TRPV1) but not those coexpressing TRPV1 and NPFR1 (pain–gal4/UAS–TRPV1/UAS–npfr1cDNA) showed capsaicin-elicited aggregation. p < 0.001.

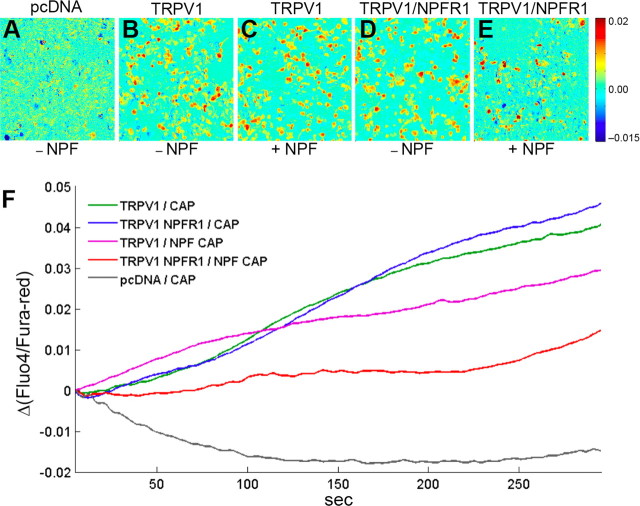

NPFR1 suppression of TRP channels in human cells

HEK293 cells have been widely used for studying the suppression of TRPV1 activity by mammalian opioid receptors (Díaz-Laviada and Ruiz-Llorente, 2005; Vetter et al., 2008). To provide direct evidence that NPF/NPFR1 signaling suppresses TRP channels through a conserved antinociceptive mechanism, we tested whether NPFR1 signaling is sufficient to suppress TRPV1 in human cells. Both npfr1 and rat TRPV1 cDNAs were coexpressed in HEK293 cells, and capsaicin-induced Ca2+ influx was imaged using Fluo-4 and Fura-red, two calcium-sensitive fluorescent dyes. We found that HEK293 cells, cotransfected with NPFR1 and rat TRPV1 cDNAs, displayed significantly reduced TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ influx relative to control groups during a 300 s test period (Fig. 6A--F). For example, HEK293 cells transfected with TRPV1 cDNA alone showed significant Ca2+ influx in response to capsaicin within 30 s, and TRPV1 channels remained active during the entire test period. Experimental cells cotransfected with both NPFR1 and TRPV1 cDNAs, in the presence of NPF, showed drastically attenuated and delayed responses to capsaicin. During the initial 200 s period, cells showed low levels of calcium-dependent fluorescence, and a subset of cells displayed an increase of intracellular Ca2+ between 200 and 300 s (Fig. 6E,F). We have observed that addition of NPF to cells transfected with TRPV1 cDNA alone caused a mild reduction in TRPV1 activity (Fig. 6F). Because HEK293 cells express endogenous NPY receptor subtypes (Y2 and Y5; our unpublished data), this mild inhibitory effect of NPF might be attributable to its cross-activation of an endogenous NPY receptor. Our results demonstrate again that NPFR1 suppression of nociceptive TRPV1 activity is mediated by a signaling mechanism conserved between flies and humans.

Figure 6.

NPFR1 suppresses Ca2+ influx mediated by rat TRPV1 in human cells. Ca2+ imaging and SOARS analysis of HEK293 cells expressing the TRPV1 channel. HEK293 cells were loaded with the Fluo-4 and Fura-red fluorescent Ca2+ indicators, stimulated by 400 nm capsaicin (CAP) and imaged for 300 s. Eigen images highlight the clusters of pixels showing statistically significant anticorrelated changes in Fluo-4 and Fura-red fluorescence intensities. A, An eigen image of HEK293 cells transfected with empty pcDNA3.1 vectors. B, C, Cells transfected with TRPV1 cDNA and stimulated by capsaicin in the absence or presence of 1 μm NPF. D, E, Cells cotransfected with TRPV1 and NPFR1 cDNAs and stimulated by capsaicin in the absence or presence of NPF. F, SOARS analysis of changes in the ratio between Fluo-4 to Fura-red fluorescence levels during the entire 300 s recording period. Each trace is generated from at least three independent experiments. For example, during a 5 s interval starting at t = 150 s, the p values are p = 1.3 × 10−12 (TRPV1/NPFR1/NPF/CAP vs TRPV1/NPFR1/CAP), p = 0.026 (TRPV1/NPFR1/NPF/CAP vs TRPV1/NPF/CAP), and p = 0.28 (TRPV1/NPFR1/CAP vs TRPV1 NPF/CAP).

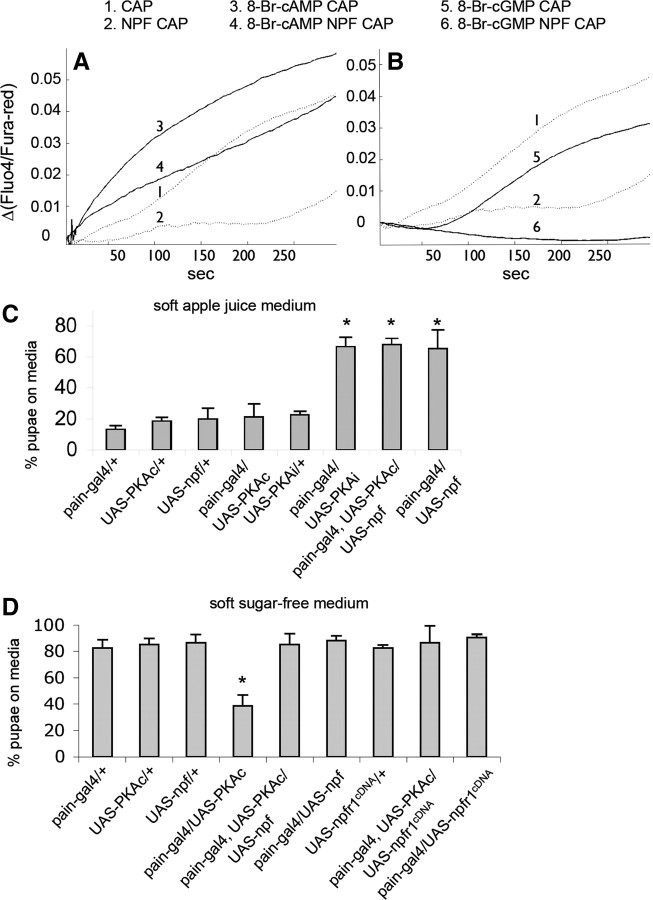

Modulation of TRPV1 by cyclic nucleotides

It has been shown that the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway potentiates TRPV1 activity in HEK293 cells and nociceptive sensory neurons and may be acutely involved in inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Bhave et al., 2002). We also observed that introduction of a cAMP analog (8-Br-cAMP) to HEK293 cells significantly increased TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ influx (Fig. 7A). Using this sensitized in vitro model, we found that NPFR1 was capable of attenuating the potentiation of TRPV1 by 8-Br-cAMP, providing additional evidence that fly NPFR1 functions well in heterologous mammal cells. In addition, 8-Br-cGMP, a cGMP analog, slightly reduced TRPV1 activity, and NPFR1 suppression of TRPV1 was significantly enhanced in the presence of 8-Br-cGMP (Fig. 7B). Pharmacological evidence suggests that NPFR1 is coupled with Gi/o-protein (Garczynski et al., 2002). Therefore, it is possible that the antinociceptive NPFR1 may involve downregulation of intracellular cAMP though inhibition of adenylyl cyclase.

Figure 7.

Effects of cyclic nucleotides, PKA, and NPFR1 on TRP channel activities. A, TRPV1 is sensitized by 8-Br-cAMP and slightly inhibited by 8-Br-cGMP (see lines 1, 3, and 5). NPFR1 significantly attenuated sensitization of TRPV1 by 8-Br-cAMP (compare lines 3 and 4; for a 5 s interval starting at t = 150 s, p = 0.023). B, NPFR1 suppression of TRPV1 is enhanced in the presence of 8-Br-cGMP (compare lines 5 and 6; p = 1.73 × 10−9). C, Quantification of avoidance response of transgenic larvae in media containing apple juice. Larvae expressing PKAi or coexpressing PKAc and NPF in PAIN neurons showed attenuated food-averse migration. Most pupated on the medium. p < 0.001. D, Quantification of avoidance response of transgenic larvae in sugar-free media. Control larvae that express UAS–PKAc alone pupated mostly outside of the agar medium. Larvae coexpressing PKAc and NPF or NPFR1 in PAIN neurons displayed attenuated food-averse migration. p < 0.001. CAP, Capsaicin.

NPF/NPFR1 suppression of PKA-induced hypersensitivity

The in vitro finding has led us to wonder whether PKA has a sensitizing effect on PAIN-mediated larval sugar aversion. Indeed, we found that postfeeding larvae expressing a constitutively active form of PKA (UAS–PKAc), driven by pain–gal4, showed aversive response to agar media regardless of the presence or absence of sugar (Fig. 7C,D). For example, a majority of pain–gal4/UAS–PKAc larvae migrated out of the sugar-free soft medium, whereas control larvae (e.g., UAS–PKAc alone) pupated mostly on the medium. Conversely, larvae expressing a dominant-negative form of PKA (UAS–PKAi), driven by pain–gal4, showed attenuated sugar aversion. These results indicate that the cAMP/PKA pathway is essential for larval aversive response to sugar, which is sensitized by increased PKA activity. Mammalian PKA has been shown to sensitize TRPV1 channels and acutely mediates hyperexcitation of nociceptive sensory neurons (Hu et al., 2001; Song et al., 2006). It is possible that fly PKA may have similar excitatory effects in PAIN neurons.

We further tested whether the NPF pathway is able to suppress sugar aversion of PKA-sensitized larvae. Postfeeding larvae coexpressing UAS–PKAc and UAS–npf, directed by pain–gal4, were placed onto apple juice and sugar-free soft agar media. We found that most of the larvae pupated on both media (Fig. 7C,D). Moreover, larvae coexpressing UAS–PKAc and UAS–npfr1cDNA also displayed similar phenotype (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that the NPF pathway has a dominant suppressive effect on the sensitization of PAIN neurons by exuberant PKA activity. Because the constitutively active PKAc is thought to be insensitive to the reduction of intracellular cAMP (Kiger et al., 1999), the Gi/o-protein-coupled NPF receptor may antagonize the PKAc effect through a cAMP-independent pathway.

Discussion

We have shown that the Drosophila NPY-like receptor NPFR1 negatively regulates fly avoidance response to diverse external stressors mediated by different subtypes of TRP family channels. Our findings suggest that the NPF/NPFR1 pathway appears to exert its suppressive effect through attenuation of TRP channel-induced neuronal excitation. Our study also provides the first evidence that the antinociceptive functions of invertebrates and mammals can be mediated by a conserved mechanism that suppresses nociceptive TRP family channels (Montell et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2004; Montell, 2005; Ramsey et al., 2006). Given the implicated role of human NPY in stress and pain resiliency (Bannon et al., 2000; Thorsell et al., 2000; Thorsell and Heilig, 2002; Zhou et al., 2008), the Drosophila NPY-like system appears to be a promising model for the identification and characterization of genetic factors that influence pain threshold and tolerance and genetic predispositions to pain disorders.

The G-protein-coupled receptors of mammalian opioid peptides and endocannabinoids are expressed in peripheral nociceptors and mediate suppression of peripheral noxious stimulation (Pertwee, 2001; Endres-Becker et al., 2007). In this study, we demonstrate that the Drosophila NPY-like system suppresses peripheral stressful stimulation in feeding larvae. Several lines of evidence suggest that NPF directly acts on sensory neurons expressing TRPA channel protein PAIN (Xu et al., 2008). First, the G-protein-coupled NPF receptor NPFR1 is expressed selectively in a subset of PAIN sensory neurons responsive to aversive sugar stimulation. Second, laser ablation of NPFR1-expressing PAIN neurons abolished larval aversion to sugar. Finally, overexpression of NPFR1 in PAIN neurons blocks sugar-stimulated TRPA channel activity. The mammalian NPY receptor Y1 is also expressed in the primary nociceptive neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia (Brumovsky et al., 2007). The pharmacological study with an Y1 agonist supports a role of Y1 in the reduction of capsaicin-stimulated release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (Gibbs and Hargreaves, 2008). Together, these findings suggest that NPY family peptides are involved in the modulation of the sensation of external stressful stimuli in flies and possibly mammals.

TRPV1 appears to be one of the primary targets of endogenous antinociceptive activities in mammals (Gunthorpe and Chizh, 2009). TRPV1 and the receptors of opioid peptides, endocannabinoids, and NPY colocalize in different nociceptors (Pertwee, 2001; Endres-Becker et al., 2007; Gibbs and Hargreaves, 2008). It has also been shown that both opioid and cannabinoid receptors suppress TRPV1-medited Ca2+ influx in primary sensory neurons or in HEK293 cells (Endres-Becker et al., 2007; Vetter et al., 2008). Now we have obtained evidence that activation of NPFR1 also suppresses TRP channel activities in larval sensory neurons and heterologous HEK293 cells. These findings suggest that a conserved signaling mechanism may underlie the suppression of peripheral stressful stimulation by invertebrate and mammalian antinociceptive activities. It remains essentially unclear how NPFR1 and mammalian opioid and cannabinoid receptors negatively regulate TRPV1 activity. Because all of these receptors are coupled with Gi/o-protein (Garczynski et al., 2002; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2002; Pertwee, 2001; Díaz-Laviada and Ruiz-Llorente, 2005; Demuth and Molleman, 2006), their antinociceptive activities may be mediated by a common mechanism involving downregulation of adenylyl cyclase and intracellular cAMP. Expression of mammalian TRPV1 renders the transgenic larvae to display migratory and grouping behaviors in response to aversive capsaicin stimulation. However, increased PKA activity in the PAIN neurons of postfeeding larvae is sufficient to elicit such behaviors without the need of any aversive chemicals in the medium. Thus, higher PKA activity appears to sensitize larval nociceptive sensory neurons. Consistent with this notion, PKA has been shown to potentiate TRP channel activity through direct phosphorylation the N-terminal domain (Bhave et al., 2002). PKA activity can also reverse the desensitized TRP channels. In the DRG sensory neurons of rats with spinal nerve ligation, PKA activity is acutely required for the peripheral neuropathic pain (Hu et al., 2001). Future experiments will determine whether the PKA-elicited independence of aversive stimulation is resulted from its sensitization of an endogenous TRP channel (e.g., PAIN).

We have obtained functional evidence that NPF is capable of suppressing sugar-elicited excitation of thoracic PAIN neurons that selectively express NPFR1 (Fig. 3). This finding lends additional support to the notion that central NPF neurons define a regulatory module that exerts a temporal control over such peripheral PAIN sensory neurons (Xu et al., 2008), and developmental downregulation of NPF in the larval brain before metamorphosis (Wu et al., 2003) is crucial for thoracic PAIN neuron-mediated sugar aversion by postfeeding larvae.

It remains to be determined how NPFR1 signaling dominantly suppresses the migratory and grouping behaviors in wild-type and PKA-overexpressing larvae. One simple explanation is that NPFR1 signaling may lead to a large reduction of the intracellular cAMP level, thereby downregulating the activity of PKA. However, we consider this explanation is not completely satisfactory because the transgenic UAS–PKAc construct encodes a constitutively active form of PKA whose activity is cAMP independent. Therefore, our finding strongly argues for the existence of a yet uncharacterized PKA-independent mechanism(s) by which NPFR1 suppresses TRP channel in PAIN neurons. Gi/o heterotrimeric proteins have been implicated in NPFR1 function (Garczynski et al., 2002), as well as modulation of ion channels (Diversé-Pierluissi et al., 1995; Zhao et al., 2008). It would be interesting to test whether NPFR1 suppression of PAIN sensory neurons may also involve direct modulation of TRP ion channels by Gi/o-proteins.

NPY family peptides have been shown to promote diverse stress-resistant behaviors (Bannon et al., 2000; Thorsell et al., 2000; Thorsell and Heilig, 2002). Overexpression of NPFR1 in flies and administration of NPY in mice rendered animals to be more willing to work for food and become more resilient to aversive taste and deleteriously cold temperature (Flood and Morley, 1991; Jewett et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2005a,b; Lingo et al., 2007). Our finding of suppression of different TRP family channels by a single receptor NPFR1 provides a molecular explanation of how an NPY family peptide could mediate resiliency to diverse gustatory, thermal, and mechanical stressors. We showed previously that, in food-deprived larvae, reduced fly insulin signaling triggers NPFR1-mdiated stressor-resistant foraging activities (Wu et al., 2005a,b). Our findings also raise the possibility that TRP family channels may be indirectly regulated by insulin signaling.

Footnotes

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AA014348 and DK058348 (P.S.). We thank U. Heberlein, K. Scott, W.D. Tracey, and M. Welsh for fly strains and A. Sornborger for help with data analysis.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Al-Anzi B, Tracey WD, Jr, Benzer S. Response of Drosophila to wasabi is mediated by painless, the fly homolog of mammalian TRPA1/ANKTM1. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyokhin A, Mille C, Messing R, Duan J. Selection of pupation habitats by oriental fruit fly larvae in the laboratory. J Insect Behav. 2001;14:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. Drosophila: a laboratory handbook. [Google Scholar]

- Bannon AW, Seda J, Carmouche M, Francis JM, Norman MH, Karbon B, McCaleb ML. Behavioral characterization of neuropeptide Y knockout mice. Brain Res. 2000;868:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS, Gereau RW., 4th cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates desensitization of the capsaicin receptor (VR1) by direct phosphorylation. Neuron. 2002;35:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broder J, Majumder A, Porter E, Srinivasamoorthy G, Keith C, Lauderdale J, Sornborger A. Estimating weak ratiometric signals in imaging data. I. Dual-channel data. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007;24:2921–2931. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.002921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky P, Shi TS, Landry M, Villar MJ, Hökfelt T. Neuropeptide tyrosine and pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HC, Hodson AC. An analytical study of population growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Ecol Monogr. 1950;20:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth DG, Molleman A. Cannabinoid signalling. Life Sci. 2006;78:549–563. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Laviada I, Ruiz-Llorente L. Signal transduction activated by cannabinoid receptors. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:619–630. doi: 10.2174/1389557054368808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diversé-Pierluissi M, Goldsmith PK, Dunlap K. Transmitter-mediated inhibition of N-type calcium channels in sensory neurons involves multiple GTP-binding proteins and subunits. Neuron. 1995;14:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres-Becker J, Heppenstall PA, Mousa SA, Labuz D, Oksche A, Schäfer M, Stein C, Zöllner C. Mu-opioid receptor activation modulates transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) currents in sensory neurons in a model of inflammatory pain. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:12–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood JF, Morley JE. Increased food intake by neuropeptide Y is due to an increased motivation to eat. Peptides. 1991;12:1329–1332. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90215-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garczynski SF, Brown MR, Shen P, Murray TF, Crim JW. Characterization of a functional neuropeptide F receptor from Drosophila melanogaster. Peptides. 2002;23:773–780. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JL, Hargreaves KM. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor effects on pulpal nociceptors. J Dent Res. 2008;87:948–952. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MD, Scott K. Motor control in a Drosophila taste circuit. Neuron. 2009;61:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SJ, Song XJ, Greenquist KW, Zhang JM, LaMotte RH. Protein kinase A modulates spontaneous activity in chronically compressed dorsal root ganglion neurons in the rat. Pain. 2001;94:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho TB, Dina OA, Levine JD. Epac mediates a cAMP-to-PKC signaling in inflammatory pain: an isolectin B4+ neuron-specific mechanism. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6119–6126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0285-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DC, Cleary J, Levine AS, Schaal DW, Thompson T. Effects of neuropeptide Y, insulin, 2-deoxyglucose, and food deprivation on food-motivated behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:267–271. doi: 10.1007/BF02311173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger JA, Jr, Eklund JL, Younger SH, O'Kane CJ. Transgenic inhibitors identify two roles for protein kinase A in Drosophila development. Genetics. 1999;152:281–290. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingo PR, Zhao Z, Shen P. Co-regulation of cold-resistant food acquisition by insulin- and neuropeptide Y-like systems in Drosophila melanogaster. Neuroscience. 2007;148:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marella S, Fischler W, Kong P, Asgarian S, Rueckert E, Scott K. Imaging taste responses in the fly brain reveals a functional map of taste category and behavior. Neuron. 2006;49:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A, Griesbeck O, Heim R, Tsien RY. Dynamic and quantitative Ca2+ measurements using improved cameleons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2135–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. Drosophila TRP channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V. The TRP channels, a remarkably functional family. Cell. 2002;108:595–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MM, Xu H, Clapham DE. TRP ion channels in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostany R, Díaz A, Valdizán EM, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Garzón J, Hurlé MA. Supersensitivity to mu-opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of the adenylyl cyclase pathway involves pertussis toxin-resistant Galpha protein subunits. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Shim JY, Assi AA, Norford D, Howlett AC. CB1 cannabinoid receptor-G protein association: a possible mechanism for differential signaling. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121:91–109. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:569–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P, Cai HN. Drosophila neuropeptide F mediates integration of chemosensory stimulation and conditioning of the nervous system by food. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:16–25. doi: 10.1002/neu.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song XJ, Wang ZB, Gan Q, Walters ET. cAMP and cGMP contribute to sensory neuron hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia in rats with dorsal root ganglia compression. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:479–492. doi: 10.1152/jn.00503.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. Predation on the soil inhabiting stages of the Mexican fruit fly. Southwest Entomol. 1995;20:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson D. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc IEEE. 1982;70:1055–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Heilig M. Diverse functions of neuropeptide Y revealed using genetically modified animals. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:182–193. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Michalkiewicz M, Dumont Y, Quirion R, Caberlotto L, Rimondini R, Mathé AA, Heilig M. Behavioral insensitivity to restraint stress, absent fear suppression of behavior and impaired spatial learning in transgenic rats with hippocampal neuropeptide Y overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12852–12857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220232997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey WD, Jr, Wilson RI, Laurent G, Benzer S. painless, a Drosophila gene essential for nociception. Cell. 2003;113:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter I, Cheng W, Peiris M, Wyse BD, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Zheng J, Monteith GR, Cabot PJ. Rapid, opioid-sensitive mechanisms involved in transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 sensitization. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19540–19550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707865200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wong AM, Flores J, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell. 2003;112:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T, Parrish CA, Xu D, Wu Q, Shen P. Drosophila neuropeptide F and its receptor, NPFR1, define a signaling pathway that acutely modulates alcohol sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2141–2146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406814102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Wen T, Lee G, Park JH, Cai HN, Shen P. Developmental control of foraging and social behavior by the Drosophila neuropeptide Y-like system. Neuron. 2003;39:147–161. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Zhao Z, Shen P. Regulation of aversion to noxious food by Drosophila neuropeptide Y- and insulin-like systems. Nat Neurosci. 2005a;8:1350–1355. doi: 10.1038/nn1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Zhang Y, Xu J, Shen P. Regulation of hunger-driven behaviors by neural ribosomal S6 kinase in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102:13289–13294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501914102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Sornborger AT, Lee JK, Shen P. Drosophila TRPA channel modulates sugar-stimulated neural excitation, avoidance and social response. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nn.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Fang Q, Straub SG, Sharp GWG. Both Gi and Go heterotrimeric G proteins are required to exert the full effect of norepinephrine on the β-cell KATP channel. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5306–5316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Zhu G, Hariri AR, Enoch MA, Scott D, Sinha R, Virkkunen M, Mash DC, Lipsky RH, Hu XZ, Hodgkinson CA, Xu K, Buzas B, Yuan Q, Shen PH, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB, Brown SM, Hauger RL, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK, Goldman D. Genetic variation in human NPY expression affects stress response and emotion. Nature. 2008;452:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature06858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Xu P, Cuascut FX, Hall AK, Oxford GS. Activin acutely sensitizes dorsal root ganglion neurons and induces hyperalgesia via PKC-mediated potentiation of transient receptor potential vanilloid I. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13770–13780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3822-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]