Abstract

We examined the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders in a community sample of 496 adolescent girls who completed annual diagnostic interviews over an 8-year period. Lifetime prevalence by age 20 was 0.6% and 0.6% for threshold and subthreshold anorexia nervosa (AN), 1.6% and 6.1% for threshold and subthreshold bulimia nervosa (BN), 1.0% and 4.6% for threshold and subthreshold binge eating disorder (BED), and 4.4% for purging disorder (PD). Overall, 12% of adolescents experienced some form of eating disorder. Subthreshold BN and BED and threshold PD were associated with elevated treatment, impairment, and distress. Peak age of onset was 17-18 for BN and BED, and 18-20 for PD. Average episode duration in months was 3.9 for BN and BED, and 5.1 for PD. One-year recovery rates ranged from 91% to 96%. Relapse rates were 41% for BN, 33% for BED, and 5% for PD. For BN and BED subthreshold cases often progressed to threshold cases and diagnostic crossover was most likely for these disorders. Results suggest that subthreshold eating disorders are more prevalent than threshold eating disorders and are associated with marked impairment.

Keywords: eating disorders, prevalence, incidence, duration, recovery, relapse, diagnostic crossover

Studies of clinical samples indicate that eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and the provisional diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), are associated with functional impairment, emotional distress, psychiatric comorbidity, a chronic course, and elevated mortality risk (Grilo et al., 2003; Herzog et al., 2000; Keel, Mitchell, Miller, Davis, & Crow, 1999; Strober, Freeman, & Morrell, 1997). Studies of community samples also indicate that these eating disorders are associated with impairment, a chronic course, and increased risk for subsequent psychiatric problems and obesity (Cachelin et al., 1999; Fairburn, Cooper, Doll, Norman, & O’Connor, 2000; Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Johnson, Cohen, Kotler, Kasen, & Brook, 2002; Patton et al., 2008; Rastam, Gillberg, & Wentz, 2003).

Relatively fewer studies have characterized the natural history of the spectrum of eating disordered behavior in adolescents using a prospective design. It is important to characterize the prevalence, incidence, duration, recovery rates, relapse rates, diagnostic progression, and diagnostic crossover for a broader range of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders during this developmental period. We use the term subthreshold eating disorders to refer to individuals who experience all of the symptoms of a particular eating disorder, but who endorse subthreshold levels of one or more symptoms (e.g., only report engaging in binge eating and compensatory behaviors once a week). We use the term partial eating disorders, to refer to individuals who report only a subset of the symptoms of a particular disorder (e.g., only report compensatory behaviors, but not binge eating or vice versa). The lack of such data for subthreshold and partial eating disorders, such as purging disorder (PD), is concerning because most adolescents who present for eating disorder treatment do not satisfy criteria for DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) AN or BN (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003; Fisher, Schneider, Burns, Symons, & Mandel, 2001; Herzog, Hopkins, & Burns, 1993; Williamson, Gleaves, & Savin, 1992). Subthreshold and partial eating disorders are associated with functional impairment, distress, suicidal attempts, medical complications, and increased risk for current and future psychiatric and medical problems (Crow, Agras, Halmi, Mitchell, & Kraemer, 2002; Garfinkel et al., 1995; Keel, Haedt, & Edler, 2005; Milos, Spindler, Schnyder, & Fairburn, 2005; Mond et al., 2006; Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008; Striegel-Moore, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 2003). Scholars have called for further research on subthreshold and partial eating disorders because they represent examples of Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) when associated with functional impairment and distress (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003; Keel, 2007; Wilson, Becker, & Heffernan, 2003).

Epidemiological studies using diagnostic interviews indicate that the lifetime prevalence among women ranged from 0.9 to 2.0% for AN, 1.1 to 4.6% for BN, 0.2 to 3.5% for BED, and 1.1 to 5.3% for PD (Favaro, Ferrara, & Santonastaso, 2003; Hudson et al., 2007; Lewinsohn, Striegel-Moore, & Seeley, 2000; Wade, Bergin, Tiggemann, Bulik, & Fairburn, 2006; Woodside et al., 2001). The lifetime prevalence of partial AN has ranged from 2.4 to 3.7% (Favaro et al., 2003; Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Patton et al., 2008; Wade et al., 2006). However, partial AN definitions were heterogeneous, including individuals who (a) endorse the criterion for a low body weight, but who endorse only one of the other three AN symptoms, (b) endorse all AN symptoms except amenorrhea, (c) endorse all AN symptoms except low body weight, or (d) endorse only two of the four AN symptoms. The lifetime prevalence of partial BN has ranged from 2.5% to 6.0% (Favaro et al., 2003; Lewinsohn et al., 2000). The definitions of partial BN were also heterogeneous, including those who (a) endorse twice-weekly binge eating for at least three months but only one other BN symptom (e.g., not reporting compensatory behaviors and weight/shape overvaluation), (b) endorse all BN symptoms except binge eating, (c) endorse all BN symptoms except that binge eating and compensatory behaviors occurred less than twice weekly, (d) endorse only compensatory behaviors, (e) endorse only binge eating, or (f) endorse only two of the three BN symptoms. Such heterogeneity is concerning because in some studies (e.g. Favaro et al., 2003) BED and PD would have been classified as partial BN. It may not be ideal to mix together individuals who endorse only binge eating, individuals who endorse only compensatory behaviors, individuals with subthreshold levels of all BN symptoms, and other permutations. Although it is an empirical question, we think there may be value in separating partial variants of BN, including BED and PD, from subthreshold cases and in requiring subthreshold cases to endorse each symptom domain, even if some are below diagnostic threshold, as this might result in more homogeneous groupings that may better predict prognosis and treatment response. Although studies have provided data on the lifetime prevalence of partial eating disorders (e.g., BED and PD), studies have not reported the prevalence of subthreshold disorders.

Further, most of the lifetime prevalence estimates are based on retrospectively reported data from studies that required participants to report on their lifetime up to the point of study entry, raising concerns about the veracity of the diagnoses (Hudson et al., 2007). Thus, the first aim of the present study was to document the lifetime prevalence of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders by age 20 using structured diagnostic interviews administered annually over 8 years in a community sample. We distinguished subthreshold AN and BN from BED and PD. As well, we used definitions of subthreshold AN, BN, and BED that required that participants endorse all DSM symptoms for those disorders, even if some or all symptoms were below diagnostic thresholds. We selected frequency cut-offs for the specific diagnoses that minimize the number of participants reporting disordered eating behavior that would fall between diagnoses. We selected minimum frequency criteria (e.g., for binge eating and compensatory behaviors) based on an earlier study that suggested that even relatively low symptom frequencies, such as twice per month, are associated with functional impairment and mental health treatment (Spoor, Stice, Burton, & Bohon, 2007). Most diagnostic criteria were developed a priori in an independent study (Stice et al., 2008).

Few prospective studies of community-recruited samples report the annual incidence of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders or the peak periods of risk for onset of these conditions. Virtually all that is known about typical ages of onset is based on retrospective data. For instance, based on retrospective reports from a community sample of young adults, Lewinsohn and associates (2000) found that the peak period of risk for onset of AN and BN was between the ages of 16 and 17. In contrast, Hudson and associates (2007) found a mean age of onset of 19 for AN, 20 for BN, and 25 for BED based on retrospective data from community-recruited adults. An improved understanding of the peak periods of risk for onset of eating disorders is vital for the optimal timing of risk factor studies and preventive interventions. This data may also advance etiologic models for these disorders by implicating a role of certain developmental transitions (e.g., menarche or school transitions). Thus, the second aim of this study was to investigate the annual incidence of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from early adolescence to young adulthood using prospective data and with a focus on identifying the peak period of risk for onset of these conditions.

Most information on the typical duration of eating disorders, recovery rates, and relapse rates is also based on retrospective data (Hudson et al., 2007). Retrospective reports from community samples indicate that the mean duration of illness is between 1.7 to 5.7 years for AN, 5.8 to 8.3 years for BN, and 8.1 to 14.4 years for BED (Hudson et al., 2007; Pope et al., 2006; Rastam et al., 2003). Retrospective reports from clinical samples indicate that the mean duration of illness is between 9.3 and 14.7 years for AN, 7.7 and 11.7 years for BN, and 14.4 years for EDNOS (Herzog et al., 1999; Milos et al., 2005). The studies involving clinical versus community samples probably found longer illness duration because duration of illness, as well as illness severity and functional impairment, predict treatment seeking (Keel et al., 2002). Yet, the wide range in estimates suggests that distinct sampling biases or differences in recovery definitions influence the estimates or that retrospective reports have questionable validity. Pope and colleagues (2006) noted that prospective studies of representative community samples are needed to provide firmer estimates of episode duration.

Some prospective studies have investigated relapse and recovery rates for patient populations. Herzog and associates (1999) found that only 6% of AN patients and 41% of BN patients showed full recovery 1 year after initiating treatment. By 7.5-year follow-up, 34% of AN patients and 74% of BN patients showed full recovery, though 40% of AN patients and 35% of BN patients relapsed after recovery during this follow-up. Fichter and Quadflieg (2007) found that 44% of AN patients, 57% of BN patients, and 65% of BED patients showed recovery 2 years after initiating treatment, with these percentages raising to 54%, 70%, and 78% respectively by 6-year follow-up. However, clinical samples may provide unrepresentative estimates of natural recovery and relapse rates. Fairburn and associates (2000) found that over 50% of community-recruited individuals with BN recovered over a 5-year follow-up without treatment, but that nearly 50% of those who recovered from BN relapsed in the subsequent year, based on repeated diagnostic interviews. Over a 6-month follow-up of another community sample, Keel and associates (2005) found that only 4% of individuals with BN and 8% of individuals with PD showed recovery. Thus, the third aim of this study was to characterize the episode duration, recovery rates, and relapse rates of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders using prospective data collected over an 8-year period.

Although most information about progression from subthreshold to threshold levels of an eating disorder and crossover from one eating disorder diagnosis to another comes from retrospectively reported data from cross-sectional studies, a handful of prospective studies have addressed these questions. Patton, Johnson-Sabine, Wood, and Wakeling (1990) found that only 11% of adolescent girls diagnosed with partial syndrome eating disorders in a large community sample showed onset of BN over a 1-year follow-up. Lewinsohn and associates (2000) found that only 28% of individuals from a community sample who showed onset of BN reported a history of partial BN previously and that the one individual who reported onset of AN did not report a previous history of partial AN. With regard to diagnostic crossover, Milos and associates (2005) investigated a large sample of individuals with various eating disorders who were primarily from treatment settings; over a 30-month follow-up, the most frequent crossover was from BN to EDNOS (27%), AN to EDNOS (20%), EDNOS to AN (13%) and AN to BN (9%). Fichter and Quadflieg (2007) found that over a 2-year follow-up of a large clinical sample the most frequent crossover was from BED to EDNOS (18%), BED to BN (15%), AN to BN (11%), and BN to EDNOS (7%). Rastam and associates (2003) reported a 22% conversion rate from AN to BN over a 6-year follow-up in a community sample. Another prospective community study found that diagnostic crossover rates were lower over a 6-month follow-up, with only 4% of individuals with PD crossing over to BN and only 8% of individuals with BN crossing over to PD (Keel et al., 2005). Thus, the fourth aim of this study was to examine diagnostic progression from subthreshold to threshold diagnoses of the same disorder and diagnostic crossover from one eating disorder to another.

In sum, this study examined the (1) lifetime prevalence and incidence of threshold and subthreshold AN, BN, BED, and PD by age 20, (2) peak periods of risk for onset of these disorders, (3) duration and relapse rates for these eating disturbances, and (4) progression from subthreshold to threshold diagnoses of the same disorder and crossover from one eating disorder to another. An additional aim was to test whether individuals with subthreshold eating disorders and those with PD evidence impairment, as indexed by elevated treatment, functional impairment, and emotional distress. We addressed these questions with data from a prospective risk factor study that followed a community sample of 496 adolescents over an 8-year period from early adolescence to young adulthood. We focused on this age-range because data suggest that the peak period of risk for eating pathology onset may occur during this time (Lewinsohn et al., 2000). We focused on females because they are approximately 10 times more likely to develop eating pathology than males (Wilson et al., 2003). We also improved upon some of the limitations of past epidemiologic studies by using more sensitive structured diagnostic interviews on an annual basis and by following participants over a longer developmental period.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 496 adolescent girls recruited from public and private middle schools in a large US city. Participants ranged from 12 to 15 years of age (M = 13) and were in 7th or 8th grade at T1. The sample included 2% Asian/Pacific Islanders, 7% African Americans, 68% Caucasians, 18% Hispanics, 1% Native Americans, and 4% who specified other/mixed racial heritage, which was representative of the schools from which we sampled. Average parental education, a proxy for socioeconomic status, was 29% high school graduate or less, 23% some college, 33% college graduate, and 15% graduate degree, which was representative of the city from which we sampled.

The study was described as an investigation of adolescent mental and physical health. An active parental consent procedure was used to recruit participants, wherein an informed consent letter describing the study was sent to parents of eligible girls (a second mailing was sent to non-responders). This resulted in an average participation rate of 56%, which was similar to other school-recruited samples that used active consent procedures and structured interviews (e.g., 61% for Lewinsohn et al., 2000). Participants completed a structured interview assessing eating disorder symptoms and had their weight and height measured by female assessors at baseline (T1) and at seven annual follow-ups (T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7, & T8). Female assessors with at least a bachelor’s degree in psychology conducted interviews. They attended 24 hours of training, wherein they received instruction in structured interview skills, reviewed diagnostic criteria for relevant DSM-IV disorders, observed simulated interviews, and role-played interviews. Assessors had to demonstrate an inter-rater agreement (kappa [k] > .80) with supervisors using tape-recorded interviews before collecting data. Assessments took place at schools, participants’ houses, or the research offices. Participants received a gift certificate or cash payment for completing each assessment.

Measures

Eating pathology

The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Interview (EDDI: Stice et al., 2008), a semi-structured interview adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), assessed DSM-IV criteria for AN, BN, and BED over the past 12-months at each of the 8 annual assessments. The EDDI does not assess subjective binge eating episodes because the 2-7 day test-retest reliability for subjective binge eating episodes (r = .33) is much lower than is the case for objective binge eating episodes (r = .85; Rizvi, Peterson, Crow, & Agras, 2000). Responses to these items allowed us to determine whether participants met criteria for threshold, subthreshold, or partial eating disorders at any time point using a computer algorithm. In accordance with previous studies (Garfinkel et al., 1995; la Grange et al., 2006; Stice et al., 2008), participants who endorsed symptoms from each domain for a particular eating disorder, but who endorsed a subthreshold level on at least one symptom were given subthreshold diagnoses. Table 1 provides the diagnostic criteria for the various eating disorders. Excessive exercise was defined as at least one hour of vigorous exercise or two hours of moderate exercise that was engaged in specifically to compensate for a binge eating episode. Fasting was defined as complete abstinence from caloric intake (meals or snacks) for approximately 24 hours or more for the purpose of weight control (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

| Subthreshold anorexia nervosa |

|

| Threshold anorexia nervosa |

|

| Subthreshold bulimia nervosa |

|

| Theereshold bulimia nervosa |

|

| Subthreshold binge eating disorder |

|

| Threshold binge eating disorder |

|

| Purging disorder |

|

Note: A diagnosis of threshold or subthreshold AN took precedence over threshold and subthreshold diagnosis of BN and BED, and PD. Although it was not possible with the definitions we used, a diagnosis of threshold or subthreshold BN took precedence over threshold or subthreshold BED and PD.

To assess test-retest reliability for this adapted interview, a randomly selected subset of 137 participants who were interviewed by the assessors for this study and another study (Stice et al., 2008) were re-interviewed by the same assessor within a 1-week period, resulting in high test-retest reliability (κ = .96) for the full range of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorder diagnoses examined herein. To assess the inter-rater agreement for the eating disorder diagnoses, a randomly selected subset of 149 participants who were interviewed by the assessors for these two studies were re-interviewed by a second blinded assessor, resulting in high inter-rater agreement (κ = .86) for the full range of eating disorder diagnoses. The EDDI has also been shown to be sensitive to detecting intervention effects and has shown predictive validity for future onset of depression in past studies (Burton & Stice, 2006; Seeley, Stice, & Rohde, 2009; Stice et al., 2008).

Body mass

The body mass index (BMI= kg/m2; Pietrobelli et al., 1998) was used for AN diagnoses. Height was measured to the nearest millimeter using portable stadiometers. Weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg using digital scales with participants wearing light indoor clothing without shoes or coats. Two measures of height and weight were obtained and averaged. The BMI shows convergent validity (r = .80 – .90) with direct measures of body fat such as dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (Pietrobelli et al., 1998). We used age- and sex-adjusted BMI centiles from the Centers for Disease Control (Faith, Saelens, Wilfley, & Allison, 2001) to determine whether participants were underweight for AN diagnoses.

Functional impairment

Impairment in the family, peer group, romantic, and school spheres was measured with 17 items from the Social Adjustment Scale-Self Report for Youth (Weissman, Orvaschel, & Padian, 1980) (response options: 1 = never to 5 = always). The original scale has shown convergent validity with clinician and collateral ratings (M r = .72), discriminates between psychiatric patients and controls, and detects treatment effects (Weissman & Bothwell, 1976). The 17-item version has shown internal consistency (α = .77), 1-week test-retest reliability (r = .83), and detects treatment effects (Burton & Stice, 2006; Stice et al., 2008).

Mental health service utilization

An item assessing the frequency of visits to mental health care providers (e.g., How often have you seen a psychologist, psychiatrist or other counselor/therapist because of mental health problems in the last 6 months?) was generated for this study. This item showed 1-year test-retest reliability (r) of .89 and sensitivity to detecting intervention effects (Stice, Shaw, Burton, & Wade, 2006).

Emotional distress

An item from the depression module of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Puig-Antich & Chambers, 1983), a semi-structured diagnostic interview, assessed subjective distress (In the last 12 months did you have a period of time when you felt sad, bad, unhappy, empty, or like crying for most of the day nearly every day?). Participants were asked to report their level of emotional distress on a month-to-month basis over the 12-month reporting window using a response option ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = severe. The 1-week test reliability for this emotional distress question was .81 in the randomly selected subset of 137 participants who were interviewed twice by independent assessors over a 1-week period, providing support for the reliability of this question. This emotional distress question also correlated positively with Buss and Plomin’s (1984) Emotionality Scale (r = .43) and the 17-item version of Weissman and associate’s (1980) Social Adjustment Scale (r = .46) and inversely with the Rosenberg (1979) Self-Esteem Scale (r = −.43), providing evidence for the construct validity of this question.

Overview of Statistical Analyses

We first report the lifetime prevalence for threshold and subthreshold AN, BN, BED, and PD, which reflect the number of participants who met criteria at baseline and those who showed onset of these eating disorders during the 8-year follow-up (Hoek, 2006). We refer to this as lifetime prevalence by age 20 because this was the mean age of participants at T8. We also report the cumulative 8-year incidence for each of these disorders, which reflect the number of participants who showed onset during the 8-year follow-up, but does not include participants who met criteria at baseline (Hoek, 2006). We next used mixed models to test whether individuals with subthreshold and partial eating disorders reported more mental health treatment, functional impairment, and emotional distress than non-eating disordered participants. Mixed models also tested whether subthreshold cases differed from threshold cases on these three impairment criteria. Models included all available data from the eight waves of the study as the dependent variable and contained a random intercept that accounted for person-level variation; eating disorder classification was the only fixed factor in the models. Variance explained (VE) is reported for significant effects, using a pseudo R2 formula (Kreft & de Leeuw, 1998). We used an alpha of .01 to reduce the risk of chance findings resulting from multiple testing.

After establishing that subthreshold eating disorders were generally associated with impairment, we collapsed threshold and subthreshold cases for each eating disorder for subsequent analyses to increase cell sizes and enhance generalizability. We then derived non-cumulative hazard curves for onset of the eating disorders for ages 14 to 20 based on annual incidence data to determine the peak period of risk for onset of each disorder. Next, for each eating disorder we reported the average episode duration in months, the 1-year and 2-year recovery rates, and the relapse rate during the follow-up period. Cases that met criteria for recovery or relapse were counted only once, even if they met criteria for each transition multiple times during the follow-up. Following Agras, Walsh, Fairburn, Wilson, and Kraemer (2000), recovery was defined as not satisfying criteria shown in Table 1 for a particular eating disorder (or any others) for at least a 1-month period. Relapse was defined as meeting criteria for another episode of an eating disorder, as defined in Table 1, after showing at least a one-month recovery from the same eating disorder. We then characterized the frequency of progressing from subthreshold level of an eating disorder to full threshold level of the same disorder (diagnostic progression) and the frequency of converting from one eating disorder category to another (diagnostic crossover). Participants had to satisfy all criteria for the subthreshold disorder specified in Table 1 (including the duration criteria) and subsequently satisfy all criteria for the threshold disorder specified in Table 1 (including the duration criteria) to be coded as showing diagnostic progression. Participants had to satisfy all criteria for one disorder specified in Table 1 (including the duration criteria) and subsequently satisfy all criteria for another disorder specified in Table 1 (including the duration criteria) to be coded as showing diagnostic crossover. Participants who showed the same diagnostic progression or crossover (e.g., transitioned from subthreshold BN to threshold BN) on multiple occasions were counted only once.

Results

Attrition

Between 1% and 8% of participants did not provide data at the various follow-up assessments, but 99% of participants provided data at baseline and at least one additional assessment. Attrition analyses indicated that there were no significant relations between any of the eating disorder diagnoses and having missing data for one or more follow-up assessments, suggesting that attrition did not introduce systematic bias.

Prevalence and Incidence of Eating Disorders

The lifetime prevalence by age 20, the cumulative incidence of onset during the 8-year follow-up, and the annual prevalence (the number of participants that exhibited a disorder during each annual interval in the follow-up period) of threshold and subthreshold AN, BN, BED, and PD are reported in Table 2. The lifetime prevalence by age 20 ranged from a low of 1% for threshold BED to a high of 6.1% for subthreshold BN. Overall, 12% of adolescents experienced some form of eating disorder. The incidence over the 8-year follow-up period was slightly lower than the age 20 lifetime prevalence because at the baseline assessment 3 participants met criteria for subthreshold BN, 2 met criteria for threshold BN, and 2 met criteria for subthreshold BED. 1, 2

Table 2.

Incidence and prevalence rates for eating disorders in a sample of 496 adolescent females followed over an 8-year period

| Annual prevalence | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | Lifetime prevalence by Age 20 n (%, CI) |

Cumulative incidence over 8-year follow-up n (%, CI) |

Yr 1 |

Yr 2 |

Yr 3 |

Yr 4 |

Yr 5 |

Yr 6 |

Yr 7 |

Yr 8 |

| Subthreshold AN | 3 (0.6 ±0.7) |

3 (0.6 ±0.7) |

0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Threshold AN | 3 (0.6 ±0.7) |

3 (0.6 ±0.7) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Subthreshold BN | 30 (6.1 ±2.1) |

26 (5.2 ±1.9) |

3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 5 |

| Threshold BN | 8 (1.6 ±1.1) |

6 (1.2 ±1.0) |

2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Subthreshold BED | 23 (4.6 ±1.8) |

21 (4.2 ±1.8) |

2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| Threshold BED | 5 (1.0 ±0.9) |

5 (1.0 ±0.9) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| PD | 22 (4.4 ±1.8) |

22 (4.4 ±1.8) |

0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

Note: AN = anorexia nervosa, BN = bulimia nervosa, BED = binge eating disorder, PD = purging disorder. Eating disorder classifications are not mutually exclusive across disorders or between subthreshold and threshold cases (e.g., a participant can be classified as being subthreshold BN at one time point, then threshold at another time point). Lifetime prevalence reflects the number of participants who met criteria at baseline and those who showed onset of these eating disorders during the 8-year follow-up. Cumulative 8-year incidence reflects the number of participants who showed onset during the 8-year follow-up, excluding participants who met criteria at baseline. Annual prevalence reflects the number of participants who met criteria for a disorder at any point during each annual assessment period.

Among individuals with subthreshold BN, the mean number of binge eating episodes per month was 3.4 (SD 2.0), the mean number of compensatory behavior episodes per month was 9.7 (SD 11.8), and the mean rating for weight and shape overvaluation was 4 (SD = 1.3). Among those with subthreshold BED, the mean number of binge eating episodes per month was 2.6 (SD = 2.2), and the mean number of compensatory behavior episodes per month was 0.11 (SD = 0.3). Among those with PD, the mean number of purging episodes (vomiting, laxative use, or diuretic use) per month was 18.9 (SD = 8.3) and the mean number of compensatory behavior episodes (with includes fasting and excessive exercise) per month was 22.8 (SD = 10.6); none reported binge episodes during their PD episode. We did not report descriptive statistics for threshold or subthreshold AN cases because the there were only 6 cases.

Impairment

Participants with subthreshold BN showed more mental health treatment (F (1, 2169) = 8.27, p = .004, VE = .02), functional impairment (F (1, 2175) = 11.12, p < .001, VE = .03), and emotional distress (F (1, 3103) = 18.18, p < .001, VE = .05) than healthy controls. Participants with subthreshold BED showed more mental health treatment (F (1, 2136) = 11.56, p < .001, VE = .03), functional impairment (F (1, 2142) = 9.14, p = .003, VE = .02), and emotional distress (F (1, 3056) = 21.00, p < .001, VE = .06) than healthy controls. Participants with PD showed more mental health treatment (F (1, 2130) = 6.79, p = .009, VE = .02) and functional impairment (F (1, 2137) = 8.32, p = .004, VE = .02), but not emotional distress (F (1, 3051) = 5.72, p = .02, VE = .02), than healthy controls per our alpha level of .01. The means and standard deviations for these groups on the impairment variables are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for the impairment variables for the eating disorder groups and non-eating disordered participants

| Eating Disorder | Mental Health Treatment M (SD) |

Functional Impairment M (SD) |

Emotional Distress M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subthreshold BN | 2.48 (3.70) | 2.36 (0.51) | 1.85 (0.69) |

| Threshold BN | 3.67 (4.71) | 2.56 (0.52) | 1.82 (0.54) |

| Subthreshold BED | 2.83 (3.82) | 2.37 (0.52) | 1.93 (0.70) |

| Threshold BED | 3.60 (4.26) | 2.39 (0.31) | 2.08 (0.59) |

| PD | 2.37 (2.58) | 2.35 (0.31) | 1.70 (0.37) |

| Healthy Controls | 1.21 (2.11) | 2.13 (0.35) | 1.47 (0.48) |

Note: AN = anorexia nervosa, BN = bulimia nervosa, BED = binge eating disorder, PD = purging disorder. Mental health treatment reflects the frequency of visits to any type of mental health care provider. Functional impairment was rates on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always, with higher scores reflecting more impairment. Emotional distress was rating on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = severe.

Participants with subthreshold BN did not differ from participants with threshold BN in levels of mental health treatment (F (1, 152) = 0.87, p = .35, VE = .003), functional impairment (F (1, 152) = 0.84, p = .36, VE = .003), and emotional distress (F (1, 216) = 0.49, p = .48, VE = .002). Participants with subthreshold BED did not differ from participants with threshold BED in levels of mental health treatment (F (1, 114) = .15, p = .70, VE = .001), functional impairment (F (1, 114) = 0.09, p = .77, VE = .000), and emotional distress (F (1, 162) = 0.01, p = .92, VE = .000). All of these effects accounted for less than 1% of the variance, suggesting that the absence of effects was not solely due to insufficient sensitivity because of modest cell sizes.

In light of the evidence that subthreshold participants consistently differed from non-eating disordered participants but did not differ from threshold participants, we combined subthreshold and threshold participants with BN and BED for subsequent analyses. After combining subthreshold and threshold cases, 32 participants exhibited subthreshold or threshold BN, 24 participants exhibited subthreshold or threshold BED, and 22 participants exhibited PD. These numbers are slightly different than the numbers reported in Table 2 because some participants showed diagnostic progression from subthreshold to threshold eating disorders and some showed diagnostic crossover.

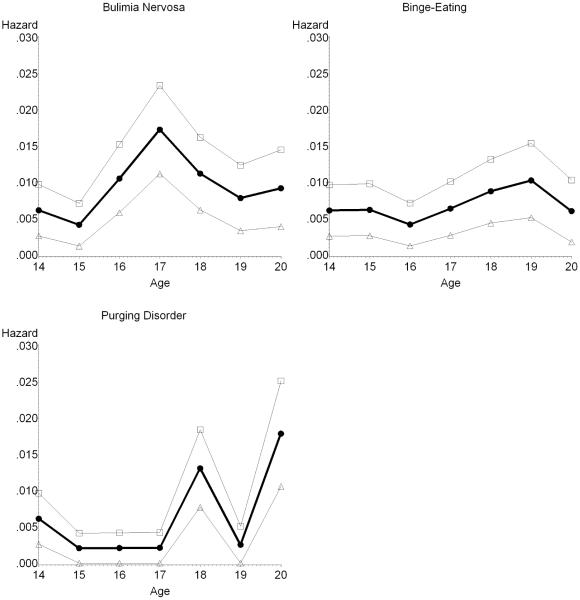

Peak Period of Risk for Onset

The non-cumulative hazard rates for each eating disorder are presented in Figure 1. We excluded cases that were symptomatic at baseline as we could not determine age of onset for these participants. Excluding cases that exhibited eating disorders at baseline, 27 participants showed onset of subthreshold or threshold BN, 22 participants showed onset of subthreshold or threshold BED, and 22 participants showed onset of PD. The plotted hazard rates suggest that risk of BN onset increased between ages 15 and 17 at which point onset peaked and began declining. The BED hazard rates did not exhibit an obvious peak, but instead suggest that risk of onset is relatively constant across adolescence. The hazard rate for PD is rare before age 18 and was generally highest in late adolescence.

Figure 1. Non-cumulative hazard functions of bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and purging disorder onset by age.

Note: The Y axis depicts the non-cumulative hazard rate for each disorder, which reflects the annual risk for onset of the condition (annual incidence). The 95% Confidence Intervals for the annual incidence data are shown.

Episode Duration

The average episode duration was 4.2 (SD = 3.3) months for threshold/subthreshold BN, 3.9 (SD = 2.3) months for threshold/subthreshold BED, and 4.7 (SD = 2.7) months for PD. Interestingly, the episode duration was not always shorter for subthreshold variants of these eating disorders (i.e., whereas the average duration of threshold BN was 3.6 [SD = 2.3], the average episode duration for subthreshold BN was 4.2 [SD = 3.6]).

Recovery and Relapse

Twenty-nine of the 32 participants with threshold/subthreshold BN recovered within 1 year (91%), 23 of the 24 participants with threshold/subthreshold BED recovered within 1 year (96%), and 21 of the 22 individuals with PD recovered in 1 year (95%). These recovery rates increased to 100% for each diagnostic category by 2-year follow-up.

Among the 32 participants who exhibited threshold/subthreshold BN, 19 experienced only 1 episode, 7 experienced 2 episodes, 3 experienced 3 episodes, 1 experienced 4 episodes, and 1 experienced 7 episodes, producing an overall relapse rate of 41%. Among the 24 participants who exhibited threshold/subthreshold BED, 16 experienced only 1 episode, 5 experienced 2 episodes, 1 experienced 4 episodes, and 2 experienced 6 episodes, producing an overall relapse rate of 33%. Twenty-one of the 22 participants who exhibited PD episodes had only 1 episode and 1 participant had 2 episodes, producing an overall relapse rate of 5%.

Diagnostic Progression

Among the 30 participants diagnosed with subthreshold BN, 5 (17%) showed subsequent onset of full threshold BN during follow-up. Among the 23 participants diagnosed with subthreshold BED, 3 (13%) showed subsequent onset of threshold BED during follow-up. It should be noted that the number of subthreshold cases is less than the total number of cases because not all participants satisfied the criteria for subthreshold diagnoses shown in Table 1 for the required 3- or 6-month period before satisfying criteria for threshold versions of the same disorder (e.g., they only reported symptom frequencies below threshold levels for a 1-month period).

Diagnostic Crossover

Crossover from BN to BED occurred in 6 of the 32 BN cases (19%) and crossover from BN to PD occurred in 0 of the 32 BN cases (0%). Crossover from BED to BN occurred in 10 of the 24 BED cases (42%) and crossover from BED to PD occurred in 1 of the 24 BED cases (4%). Crossover from PD to BN occurred in 1 of the 22 PD cases (5%) and crossover from PD to BED occurred in 2 of the 22 PD cases (9%).

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to investigate the lifetime prevalence of threshold and subthreshold AN, BN, BED, and PD by age 20. Results indicated that the prevalence rates were 0.6% and 0.6% for threshold and subthreshold AN, 1.6% and 6.1% for threshold and subthreshold BN, 1.0% and 4.6% for threshold and subthreshold BED, and 4.4% for PD. These findings are important because this is the first study to report lifetime prevalence of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community-recruited sample that completed annual diagnostic interviews during the entire adolescent period. Most previous studies relied on retrospective reports or less frequent interviews. It is reassuring that our lifetime prevalence estimates through age 20 are in the range reported in past epidemiologic studies of young adults for threshold (0.7 to 2.0%) and partial (2.4 to 3.7%) AN, and threshold (1.2 to 4.6%) and partial (2.5 to 6.0%) BN (Favaro et al., 2003; Kjelsas et al., 2004; Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Patton et al., 2008). The prevalence estimates for PD and subthreshold BED are novel contributions, as these are the first lifetime prevalence estimates from a US sample involving diagnostic interviews, though our PD prevalence estimate is similar to the lifetime prevalence rate of 5.3% for PD in Australia from a cross-sectional epidemiologic study (Wade et al., 2006).

The present findings indicate that many more participants received a diagnosis for subthreshold levels of AN and BN and other EDNOS diagnosis (BED and PD) in total (17.3%) than received a diagnosis for DSM-IV AN and BN (2.2%). The fact that a similar pattern has emerged in samples of young adult women (e.g., Favaro et al., 2003; Lewinsohn et al., 2000) suggests that the stage may be set for eating pathology in adolescence, underscoring the importance of early prevention and treatment intervention. The evidence that subthreshold BN and other EDNOS eating disorder diagnoses are associated with elevated functional impairment, emotional distress, and treatment seeking also underscores the importance of early intervention. In total, 12% of the participants met criteria for one or more of these eating disorders during adolescence, suggesting that many young women pass through a period of disordered eating.

The second aim of this study was to examine the peak periods of risk for onset of the various eating disorders. Peak period of risk for onset was between 17 and 18 for BN and BED, and was between 18 and 20 for PD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the peak period of risk for onset of PD using prospective data. The evidence that eating pathology tends to emerge in mid to late adolescence suggests that developmental experiences that typically occur in this age period, such as heightened importance placed on conforming to the thin-ideal precipitated by more time spent with peers and dating partners, may increase risk for eating pathology. It is possible that appetitive drive to consume high-fat and high-sugar foods increases during adolescence, potentially because of some changing biological process (e.g., hormonal influence) or from conditioning processes during this period.

The third aim of this study was to examine the episode duration, recovery rates, and relapse rates for these eating disturbances. Average episode duration in months was 4.2 for threshold/subthreshold BN, 3.9 for threshold/subthreshold BED, and 4.7 for PD. Although these durations are considerably shorter than average duration estimates from treatment-seeking samples (e.g., Agras et al., 2000; Milos et al., 2005), other studies that examined community samples found relatively shorter duration estimates (e.g., Lewinsohn et al., 2000). Presumably, individuals with the most severe and chronic forms of eating disorders seek treatment, whereas less severe eating pathology may resolve more quickly.

Recovery rates were high in this sample. Specifically, 1-year recovery rates were 91% for threshold/subthreshold BN, 96% for threshold/subthreshold BED, and 95% for PD. These rates are much higher than reported in prospective studies of treatment-seeking samples (e.g., Fichter & Quadflieg, 2007; Herzog et al., 1999), probably due to the fact that individuals who seek treatment show more extreme eating pathology. Yet, the fact that Fairburn and associates (2000) found a 50% recovery rate over a 1-year period in their prospective study of community-recruited individuals with threshold BN suggests that the relatively high recovery rates reported in the present study may have emerged because most of the present participants reported subthreshold eating disorders. Another factor that might have contributed to the lower recovery rates reported in previous studies is that they used more conservative definitions of recovery. For instance, Herzog and associates (1999) required the absence of symptoms or the presence of only residual symptoms for a period of 8 consecutive weeks for full recovery (versus 4 weeks for the present report). Reviews have established that there is wide variation in definitions of recovery that impact descriptive data regarding recovery rates for eating disorders (Couturier & Lock, 2006; Keel, Mitchell, Davis, Fieselman, & Crow, 2000). Of note, however, the 1-year recovery rates were identical for each eating disorder even if we required the absence of diagnostic criteria for at least a 3-month period.

Relapse rates in the present study were 41% for threshold/subthreshold BN, 33% for threshold/subthreshold BED, and 5% for PD. These findings are novel because few studies have characterized the course of subthreshold eating pathology and PD. It was noteworthy that relapse rates were highest for BN and BED, which may imply that recurrent binge eating results in some fundamental change that increases risk for re-emergence of binge eating, such as conditioning in which cues associated with previous binge eating episodes trigger cravings that result in the re-emergence of this behavior (Jansen, 1998).

The fourth aim of this study was to characterize progression from subthreshold to threshold diagnoses of the same eating disorder and crossover from one eating disorder to another. Between 13% and 17% of subthreshold cases progressed to threshold cases for BN and BED during the study period. The diagnostic progression rates for BN and BED are similar to the relatively low rates observed in two previous prospective studies (Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Patton et al., 1990). Higher rates of diagnostic progression have emerged in treatment-seeking samples: Herzog and associates (1993) found that approximately 50% of treatment-seeking women with a partial eating disorder in a small case series went on to develop a full threshold eating disorder.

There was also evidence of diagnostic crossover from one disorder to another in the present community-recruited sample. Crossover was most likely from BED to BN (42% of BED cases), followed by BN to BED (19% of BN cases). The rates of crossover from PD to BN and BED were much lower, similar to crossover rates observed in the one other prospective study of a community sample of PD cases (Keel et al., 2005). The crossover estimates from BN to BED and vice versa were higher than the rates observed in Striegel-Moore and associates’ (2001) cross-sectional study (11% and 29% respectively), potentially because the latter study focused only on full threshold cases and relied on retrospective report. This moderate diagnostic crossover suggests some fluidity in diagnoses, which might be useful to factor into nosological frameworks, such as the DSM. Fairburn and Harrison (2003) argued that this fluidity implies a fundamental problem with our current diagnostic system. Given that the most common crossover was from BN to BED and vice versa, future studies should test whether alternative diagnostic approaches, such as a broad binge eating syndrome that subtypes individuals as to whether they show consistent, intermittent, or no regular use of compensatory behaviors, has greater predictive validity than the present BN versus BED distinction in terms of clinical course and response to treatment.

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. First, the descriptive statistics should be interpreted with caution because the prevalence and incidence are relatively low and the sample size for this risk factor study was small relative to epidemiological studies. Yet data from smaller studies in which participants complete multiple detailed diagnostic interviews over a long period of time complements data provided by large cross-sectional epidemiological studies that rely on retrospective reports. Ideally, the present assessment-intensive design would be used with larger sample sizes. Second, retrospective data suggest that the average age of onset for certain eating disorders, including BED and PD, occur in the early twenties (Hudson et al., 2007; Wade et al., 2006; Stiegel-Moore et al., 2001), implying that the estimates regarding peak periods of risk, prevalence, recovery, relapse, diagnostic progression, and diagnostic crossover may be biased low, particularly give that the peak age of onset for PD was age 20. Interestingly, however, Patton and associates (2008) found that few new cases of threshold or partial AN or BN emerged during young adulthood in a prospective study. It is also possible that participants showing onset during adolescence may differ qualitatively than those showing onset during young adulthood. Third, the descriptive statistics should also be interpreted with care given the provisional nature of the definitions for subthreshold and partial eating disorders. Fourth, participants who met criteria for an eating disorder were given a referral and encouraged to seek treatment, which may have affected certain descriptive statistics reported here (e.g., treatment rates, mean duration, and diagnostic crossover). Fifth, the moderate recruitment rate may limit generalizability of the findings because those who enrolled may differ from those who did not with regard to eating pathology. Although our prevalence estimates for eating disorders are within the range observed in larger epidemiologic samples, future studies should strive for higher recruitment rates. Finally, participants were required to report on their symptoms over the previous 12 months at each annual assessment, which may have introduced error.

Clinical and Research Implications

Findings suggest that eating pathology is more common that previously suspected, affecting approximately 12% of adolescent girls. Although these conditions were not associated with the protracted course and high relapse rates suggested by some previous clinical samples, they were characterized by functional impairment, emotional distress, treatment seeking, diagnostic progression and crossover, and moderate relapse rates. These data suggest that prevention efforts should be given a priority, particularly those that have been found to reduce risk for onset of this broader array of eating disorders. Findings also emphasize the importance of offer eating disorder prevention programs during middle adolescence, rather than young adulthood, if the goal of reducing risk for onset of eating pathology is to be realized. The findings may also have etiologic implications. For instance, the high diagnostic crossover between BN and BED imply that there may be shared risk factors for these conditions, but that PD may be caused by a qualitatively distinct set of etiologic processes. Finally, although these findings provide important data bearing on the natural course of eating pathology among adolescents in the community, it will be vital for larger studies involving more representative samples to investigate this natural course of the various forms of eating pathology.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a career award (MH01708) and a research grant (MH/DK61957) from the National Institutes of Health.

Thanks go to project research assistants Sarah Kate Bearman, Cara Bohan, Emily Burton, Melissa Fisher, Lisa Groesz, Jenn Tristan, Natalie McKee, Katherine Presnell, and Katy Whitenton, a multitude of undergraduate volunteers, the Austin Independent School District, and the participants who made this study possible.

Footnotes

When we omitted the amenorrhea criterion for AN, the lifetime prevalence by age 20 increased from 3 to 9 for subthreshold AN and from 3 to 10 for threshold AN; the cumulative incidence over the 8-year follow-up increased from 3 to 9 for subthreshold AN and from 3 to 10 for threshold AN.

When we require only a 3-month duration rather than a 6-month duration for BED, the lifetime prevalence by age 20 remained 23 for subthreshold BED and increased from 5 to 6 for threshold BED; the cumulative incidence over the 8-year follow-up remained 21 for subthreshold BED and increased from 5 to 6 for threshold BED.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

References

- Agras WS, Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:459–466. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Stice E. Evaluation of a healthy-weight treatment program for bulimia nervosa: A preliminary randomized trial. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2006;44:1727–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH, Elder KA, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. Natural course of a community sample of women with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:45–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199901)25:1<45::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Lock J. What is Recovery in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:550–555. doi: 10.1002/eat.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Agras WS, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: A multicenter study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32:309–318. doi: 10.1002/eat.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith M, Saelens B, Wilfley D, Allison D. Behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity: Current status, challenges, and future directions. In: Thompson JK, Smolak L, editors. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2001. pp. 313–340. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn C, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th edition Guilford; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman PA, O Connor ME. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003;361:407–416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro A, Ferrara S, Santonastaso P. The spectrum of eating disorders in young women: A prevalence study in a general population sample. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:701–708. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000073871.67679.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Quadflieg N. Long-term stability of eating disorder diagnoses. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S61–S66. doi: 10.1002/eat.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Schneider M, Burns J, Symons H, Mandel FS. Differences between adolescents and young adults at presentation to an eating disorder program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:222–227. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy S, et al. Bulimia nervosa in a Canadian community sample: Prevalence and comparison of subgroups. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1052–1058. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Pagano ME, et al. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified is not influenced by personality disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34:319–330. doi: 10.1002/eat.10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Selwyn SE, Ekeblad ER, Flores AT, et al. Recovery and relapse in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A 7.5 year follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Greenwood DN, Dorer DJ, Flores AT, Ekeblad ER, Richards A, et al. Mortality in eating disorders: A descriptive study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:20–26. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200007)28:1<20::aid-eat3>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Hopkins J, Burns CD. A follow-up study of 33 subdiagnostic eating disordered women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;14:261–267. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199311)14:3<261::aid-eat2260140304>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence, and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:389–394. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J, Hiripi E, Pope H, Kessler R. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A. A learning model of binge eating: Cue reactivity and cue exposure. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:257–272. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Cohen P. Psychiatric disorders associated with risk for the development of eating disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1119–1128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1119. Kotler, & L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK. Purging disorder: Subthreshold variant or full-threshold eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S89–S94. doi: 10.1002/eat.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, Delinsky SS, Franko DL, Blais MA, Keller MB, Herzog DB. Predictors of treatment utilization among women with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:140–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Haedt A, Edler C. Purging disorder: An ominous variant of bulimia nervosa? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:191–199. doi: 10.1002/eat.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Mitchell JE, Davis TL, Fieselman S, Crow SJ. Impact of definitions on the description and prediction of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:377–386. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4<377::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Mitchell JE, Miller KB, Davis TL, Crow SJ. Long-term outcome of bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:63–69. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelsas E, Bjornstrom C, Gotestam KG. Prevalence of eating disorders in female and male adolescents (14-15 years) Eating Behaviors. 2004;5:13–25. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, De Leeuw J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling. Sage Publications; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- le Grange D, Binford RB, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Klein MH, et al. International Journal of Eating Disorders. Vol. 39. 2006. DSM-IV threshold versus subthreshold bulimia nervosa; pp. 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milos G, Sindler A, Schnyder U, Fairburn CG. Instability of eating disorder diagnoses: Prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:573–578. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J, Hay P, Rodgers B, Owen C, Crosby R, Mitchell J. Use of extreme weight control behaviors with and without binge eating in a community sample: Implications for the classification of bulimic-type eating disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;39:294–302. doi: 10.1002/eat.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sanci L, Sawyer S. Prognosis of adolescent partial syndromes of eating disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:294–299. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Johnson-Sabine E, Wood K, Mann AH, Wakeling A. Abnormal eating attitudes in London schoolgirls – A prospective epidemiological study: Outcome at 12-month follow-up. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20:383–394. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli A, Faith M, Allison D, Gallagher D, Chiumello G, Heymsfield S. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity among children and adolescents: A validation study. Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;132:204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Lalonde JK, Pindyck LJ, Walsh T, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating disorder: A stable syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2181–2183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (6-18 years) Western Psychiatric Institute; Pittsburgh: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rastam M, Gillberg C, Wentz E. Outcome of teenage-onset anorexia nervosa in a Swedish community-based sample. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;12:S78–S90. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-1111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:311–316. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. Basic Books; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Spoor ST, Stice E, Burton D, Bohon C. Relations of bulimic symptom frequency and intensity to psychosocial impairment and health care utilization: Results from a community-recruited sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:505–514. doi: 10.1002/eat.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley J, Stice E, Rohde P. Screening for depression prevention: Identifying adolescent girls at high risk for future depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0014741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti N, Spoor S, Presnell K, Shaw H. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:329–340. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Burton E, Wade E. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Cachelin FM, Dohm FA, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. Comparison of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa in a community sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:157–165. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200103)29:2<157::aid-eat1005>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood of women who experience an eating disorder during adolescence. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:587–593. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046838.90931.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: Survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10-15 years in a prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22:339–360. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TD, Bergin JL, Tiggemann M, Bulik CM, Fairburn CG. Prevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohort. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:121–128. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:1111–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M, Orvaschel H, Padian N. Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales comparison of mothers, and children’s reports. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorder. 1980;168:736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DA, Gleaves DH, Savin SS. Empirical classification of eating disorder not otherwise specified: Support for DSM-IV changes. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1992;14:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Becker CB, Heffernan K. Eating Disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child Psychopathology. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 2003. pp. 687–715. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside DB, Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Kaplan AS, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy SH. Comparison of men with full or partial eating disorders, men without eating disorders, and women with eating disorders in the community. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:570–574. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]