Abstract

Background and objectives: Despite potential significance of fatigue and its underlying components in the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases, epidemiologic data showing the link are virtually limited. This study was designed to examine whether fatigue symptoms or fatigue's underlying components are a predictor for cardiovascular diseases in high-risk subjects with ESRD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: 788 volunteer patients under hemodialysis therapy (506 male, 282 female) completed the survey between October and November 2005, with the follow-up period up to 26 months to monitor occurrence of fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events. The questionnaire consisted of 64 questions, and promax rotation analysis of the principal component method conceptualized eight fatigue-related factors: fatigue itself, anxiety and depression, loss of attention and memory, pain, overwork, autonomic imbalance, sleep problems, and infection.

Results: 14.7% of the patients showed fatigue scores higher than twice the SD of the mean for healthy volunteers. These highly fatigued patients exhibited a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular events (hazard ratio: 2.17; P < 0.01), with the relationship independent of the well-known risk factors, including age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease history, and inflammation and malnutrition markers. Moreover, comparisons of the risk in key subgroups showed that the risk of high fatigue score for cardiovascular events was more prominent in well-nourished patients, including lower age, absence of past cardiovascular diseases, higher serum albumin, and high non-HDL cholesterol.

Conclusions: Fatigue can be an important predictor for cardiovascular events in patients with ESRD, with the relationship independent of the nutritional or inflammatory status.

The importance of behavioral and psychosocial factors in the prevention, development, and treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) has been increasingly recognized in the medical and scientific communities (1–3). Physical and mental activities, including anger, sadness, frustration, and tension, can trigger daily life ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease (1,4–6). The presence of mental stress-induced ischemia is associated with significantly higher rates of subsequent fatal and nonfatal cardiac events, potentially mediated by the occurrence of myocardial ischemia (7). Conversely, the addition of psychosocial treatments or stress management to standard rehabilitation regimens is shown to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with acute myocardial infarction (8,9).

Among behavioral and psychosocial factors, fatigue is an important bio-alarm for human health, as well as fever and pain (10). Fatigue has come to be recognized as a newly recognized important syndrome (chronic fatigue syndrome) (11–13), as well as a serious symptom of many chronic illnesses. Fatigue can not only significantly impair a person's functioning and have a negative effect on his or her health-related quality of life (QoL), without which a person might drop into unrecoverable exhaustive state and, in the most severe case, can even die, referred to in Japanese as Karoshi. The major medical causes of Karoshi deaths are heart attack and stroke due to stress (14,15).

Despite the potential significance of fatigue symptoms in the occurrence of CVD, epidemiologic data showing the link are virtually limited. Hardy and Studenski (16) recently reported that a single simple question, “Do you feel tired most of the time?” identifies older adults with a higher risk of mortality. Epidemiologic evidence also suggests that vital exhaustion as assessed by simple questionnaires belongs to the precursors of different manifestations of coronary artery disease (17–19). Although the vitality construct captures a mild reduction in energy level, it fails to capture the negative aspects of fatigue, such as weakness, lack of motivation, and difficulty with concentration (20,21). Thus, these reports emphasize the need to identify and characterize the significance of fatigue and its underlying components (overwork, autonomic imbalance, depression and anxiety, loss of attention, etc.) to develop and test specific treatments, and to determine whether improvement leads to decreased morbidity and mortality. Moreover, it is intriguing to test whether fatigue and its related components are predictors for cardiovascular events in subjects at higher risk, such as patients with ESRD (22).

Fatigue is one of the most frequent symptoms of patients with ESRD undergoing maintenance dialysis therapy. The prevalence of fatigue ranges from 60% to as high as 97% in ESRD patients on long-term dialysis therapy (23–26). Recognition of fatigue in dialysis patients may be difficult because recovery from fatigue has great interpatient variability (27). Despite the importance of fatigue symptoms in ESRD patients, both the presence and severity of fatigue remain largely unrecognized (28).

In this study, we surveyed the prevalence and severity of fatigue in 788 hemodialysis patients by using recently established new fatigue scale (29). We examined whether the subjective fatigue scores can be a predictor for future cardiovascular events.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The outpatient chronic dialysis hospitals in the Osaka district of Japan participated in this protocol. A total of 1927 dialysis patients in the Osaka district (Inoue Hospital (n = 972), Shirasagi Hospital (n = 815), and Okada Clinic (n = 140)) were asked to participate in the survey, and 850 patients (44.1%) completed the survey. Peritoneal dialysis patients (n = 62) were excluded, and the data for 788 hemodialysis patients (male: n = 506; female: n = 282; Inoue Hospital, n = 343; Shirasagi Hospital, n = 333; and Okada Clinic n = 112) were used for final analyses. All survey-completing patients agreed to be enrolled in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocol of the study was approved by the ethics committees at the Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (approval no. 1217) and at individual hospitals. The survey was performed between October and November 2005. Clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the hemodialysis patients

| No. of patients (no. male/no. female) | 788 (506/282) |

| Age, yr | 61.8 ± 10.7 |

| Dialysis duration, yr | 7.6 (0.1–45.0) |

| Presence of diabetes, % | 25.4 |

| Presence of hypertension, % | 84.8 |

| Presence of cardiovascular disease history, % | 24.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.2 ± 3.6 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 152.6 ± 22.2 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.3 ± 9.9 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 10.1 ± 1.1 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.30 (0.0–7.5) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.65 ± 0.31 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.66 ± 2.58 |

| Non-HDL, mmol/L | 2.95 ± 0.88 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.19 ± 0.37 |

| High score for fatigue-related eight factors, % | |

| fatigue | 14.7 |

| anxiety and depression | 12.5 |

| loss of attention and memory | 8.4 |

| pain | 26.9 |

| overwork | 8.0 |

| autonomic imbalance | 26.1 |

| sleep problems | 8.3 |

| infection | 17.5 |

Numerical data are shown as mean ± SD. Data with skewed distribution are shown as median (range). For fatigue-related eight factors, the patients with the scores exceeding twice the SD of the mean of healthy subjects were considered a high-score group.

For validation of the 64 items on the questionnaires, fatigue score and its related components were compared with Chalder fatigue scale (20) and Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQoL) questionnaires (n = 143) (30). Basal data from the clinical trial “Efficacy of the nutrient supplement ‘AMP01’ for the fatigue of the hemodialysis patients” (UMIN000001055) were used for the analyses. This clinical trial was designed to examine the efficacy of nutrient support on subjective (questionnaires) and quantitative (autonomic function, viral reactivation, and hormonal levels) measures for fatigue.

Fatigue Scale

The questionnaire associated with fatigue scale (Table 2) consisted of 64 questions as described previously (29). The subjects were asked to rate how often in a recent week they experienced the symptoms, using a Likert scale (0 to 4). Eight factors were calculated as a result of principal factor analysis with promax rotation, and these were named as fatigue, anxiety and depression, loss of attention and memory, pain, overwork, autonomic imbalance, sleep problems, and infection. Forty-two questions (footnote in Table 2), which did not overlap among scales (load >0.4), were used to calculate each scale. Because each factor has a different number of questions, each score is recalculated to go up to 20 points.

Table 2.

Sixty-four items of the questionnaire

| No. | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Feeling shaky on my feet |

| 2 | Feeling restless due to anxiety |

| 3 | Getting a low backache |

| 4 | Dozing off frequently |

| 5 | Having a mild fever |

| 6 | Feeling less able to think |

| 7 | My legs feel heavy lately |

| 8 | Having difficulty breathing |

| 9 | Feeling so tired that I want to lie down at times |

| 10 | Feeling tired and without energy |

| 11 | Being reluctant to socialize with people |

| 12 | Being unable to sleep well |

| 13 | My eyes easily become tired |

| 14 | Not feeling energetic lately |

| 15 | Becoming very tired with just a small amount of exercise or work |

| 16 | Catching a cold often, and it is difficult to get better |

| 17 | Forgetting things at times |

| 18 | Feeling sluggish lately |

| 19 | My eyelids and muscles twitch |

| 20 | Cannot help feeling disgusted with myself |

| 21 | Feeling depressed |

| 22 | Feeling muscle pain recently |

| 23 | My arms feel heavy lately |

| 24 | Having no time to rest and relax |

| 25 | A hoarse voice |

| 26 | Unable to get enthusiastic about things |

| 27 | Unable to have fun no matter what I do |

| 28 | Feeling anxious about the condition of my own body |

| 29 | Having no desire to work |

| 30 | Unable to remember small things |

| 31 | A recent lack of physical energy |

| 32 | Being busy and unable to get enough sleep |

| 33 | Having thoughts of being better off dead |

| 34 | Not wanting to read or write anything |

| 35 | Getting swollen lymph nodes |

| 36 | A portion of what is in front of my eyes disappeared at times |

| 37 | Thinking about leaving my current job at times |

| 38 | Becoming irritated and touchy |

| 39 | Becoming dizzy when there is bright light |

| 40 | My motion getting slower |

| 41 | Getting headaches and feeling heavy-headed |

| 42 | Having an upset stomach |

| 43 | Thinking that the way I get tired recently is abnormal |

| 44 | Having work and things to do until late at night |

| 45 | Getting caught in a daze |

| 46 | Getting stiff shoulders easily |

| 47 | Making many careless mistakes |

| 48 | Feeling nauseous and sick to my stomach |

| 49 | Having a heavy workload, and it is burdensome |

| 50 | General fatigue lately |

| 51 | Even after a night's sleep do not feel refreshed |

| 52 | Not having self-confidence in the things I do |

| 53 | A decline in my ability to concentrate |

| 54 | Cannot help but feel sleepy lately |

| 55 | Going to work every day is very difficult |

| 56 | Having no desire to eat lately |

| 57 | Getting a sore throat |

| 58 | My back feels heavy lately |

| 59 | No matter what, I sleep too much |

| 60 | Dropping things I am holding in my hand |

| 61 | Even after returning home, being unable to get work off my mind |

| 62 | Having sore joints |

| 63 | Breaking out into a cold sweat at times |

| 64 | Getting shaky hands and/or legs |

Principal factor analysis with promax rotation of the items conceptualized in eight factors. Fatigue: 9, 10, 15, 18, 31, 43, 50, 51; anxiety and depression: 2, 11, 20, 21, 26, 27, 29, 33, 38, 52; loss of attention and memory: 6, 17, 30, 47, 53; pain: 7, 22, 23, 58, 62; overwork: 24, 32, 44, 49, 61; autonomic imbalance: 36, 39, 63, 64; sleep problems: 4, 54, 59; Infection: 35, 57.

To obtain reference values for each factor, the volunteers in the Osaka Clinical Trial Volunteer's Association organized by the Center for Drug & Food Clinical Evaluation, Osaka City University Hospital, Osaka, Japan, were asked to complete the 64-item questionnaire. The questionnaire was sent to 328 consenting participants in September to December 2007, and all subjects completed the survey. The subjects with known diseases or taking medications were excluded, and the data of 171 healthy volunteers (age: 45.4 ± 14.0 years; male: 29.8%) were used to calculate reference scales. The means and SDs of the eight factors are 5.2 ± 4.1 (fatigue), 4.1 ± 3.8 (anxiety and depression), 6.0 ± 4.3 (loss of attention and memory), 3.9 ± 3.3 (pain), 4.0 ± 4.0 (overwork), 1.6 ± 2.4 (autonomic imbalance), 4.7 ± 4.2 (sleep problems), and 1.5 ± 2.7 (infection). The patients with the scores exceeding twice the SD of the mean of healthy subjects were considered a highly scored group, and the outcomes were compared with the normal group (equal or less than mean +2 SD of healthy).

Laboratory Evaluation

The laboratory values were measured immediately before the initiation of dialysis treatment. All laboratory measurements were performed by routine assays by use of automated methods.

Outcome Data Collection

The subjects were followed up to December 2007, with a median follow-up period of 26 (1–26 months) months. Date and cardiovascular events were obtained by reviewing the clinical records by physicians in individual hospitals who were blinded to patients' fatigue scores. For the patients that moved away to other dialysis units, we reviewed the questionnaire forms filled by the attending physicians at the units. Primary outcome was fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events. During the follow-up, 82 fatal (n = 15) and nonfatal (n = 67) cardiovascular events occurred. Fatal cardiovascular events included five acute myocardial infarctions, two ischemic strokes, four hemorrhagic strokes, two ischemic bowel diseases, and two sudden deaths, which was defined as a witnessed death that occurred within 1 hour after the onset of acute symptoms, with no evidence of accident or violence. For nonfatal cardiovascular events, ECG-documented anginal episodes and myocardial infarction (n = 42), as well as ischemic (n = 15) or hemorrhagic (n = 10) stroke documented by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was accurately recorded. As the secondary outcome, the date and all causes of death events were recorded. The 48 deaths included cardiovascular events (n = 15), cancer (n = 3), infectious disease (n = 11), liver cirrhosis (n = 1), acute pancreatitis (n = 1), uremia (n = 1), pulmonary edema without any evidence of myocardial infarction (n = 3), hyperpotassemia (n = 3), and death of unknown causes (n = 10).

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD. Median (limits of observed values) was given for duration of hemodialysis, C-reactive protein, and the follow-up periods because of their skewed distribution. Factors associated with high fatigue score were evaluated by logistic regression analyses. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method with logrank test. Prognostic variables for survival were examined using the univariate or multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All of these analyses were performed using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Tokyo, Japan) or StatView 5 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

We first examined the reliability and validity of the 64-item questionnaire in ESRD patients. In ESRD subjects, conceptualized eight factors [(1) fatigue; (2) anxiety and depression; (3) loss of attention and memory; (4) pain; (5) overwork; (6) autonomic imbalance; (7) sleep problems; and (8) infection] accounted for 52.5% of the total variance. Cronbach α for each factor was 0.91, 0.92, 0.89, 0.82, 0.86, 0.71, 0.74, and 0.64, respectively. In 143 hemodialysis patients, the correlation coefficients between the factors and Chalder fatigue scale were 0.72, 0.74, 0.66, 0.54, 0.22, 0.48, 0.49, and 0.27, respectively. Each coefficient showed statistical significance. The fatigue score (factor 1) was strongly and inversely associated with vitality (r = −0.66), emotional role (−0.50), symptoms/problems (−0.62), and effect of kidney disease (−0.52) in KDQoL, with all relationships highly significant (P < 0.001). The fatigue score was also significantly (P < 0.05) and inversely associated with many of the components of KDQoL: physical functioning (r = −0.30), physical role (−0.36), bodily pain (−0.46), general health (−0.44), social functioning (−0.32), burden of kidney disease (−0.48), cognitive function (−0.43), quality of social interaction (−0.42), sleep (−0.42), social support (−0.18), and dialysis staff encouragement (−0.20). The fatigue score was not significantly associated with work status, sexual function, and patient satisfaction.

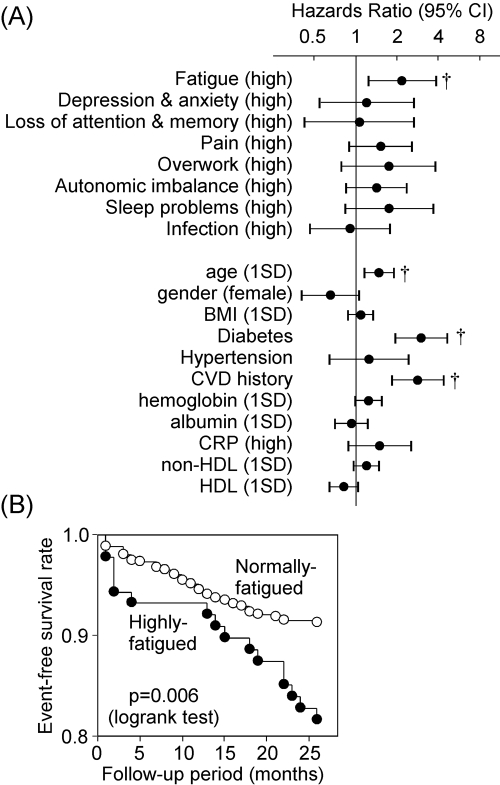

The survey exhibits that 14.7% of the patients belonged to the highly scored group for fatigue score. Logistic regression analyses revealed that only higher age and higher serum glucose levels were positively and significantly associated with high fatigue score, whereas gender, dialysis duration, diabetes, hypertension, CVD history, body mass index (BMI), BP, blood hemoglobin, serum C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, and non-HDL and HDL cholesterol were not significantly associated (data not shown). The outcomes for cardiovascular events of the highly fatigued patients were compared with the rest of the patients (equal or less than mean +2 SD of healthy) by Cox proportional hazards model. As shown in Figure 1A, highly fatigued patients exhibited significantly (P = 0.008) higher risk for cardiovascular events than normal-score patients (hazard ratio: 2.17; 95% confidence interval: 1.23 to 3.85). Kaplan-Meier analysis also confirmed the findings (Figure 1B). The percentage of high scores for other fatigue-related factors, including depression and anxiety, loss of attention and memory, pain, overwork, autonomic imbalance, sleep problems, and infection were 12.5, 8.4, 26.9, 8.0, 26.1, 8.3, and 17.5%, respectively (Table 1). However, in contrast to the high fatigue score, all of the high scores failed to significantly predict cardiovascular events in this cohort (Figure 1A). Higher age, presence of diabetes, and past CVD history were also the significant risks for cardiovascular events in these patients (Figure 1A). None of the eight components, including fatigue, were significantly associated with total mortality in this cohort (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Fatigue score is a predictor for CVDs in patients undergoing hemodialysis treatment. (A) Univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses. For fatigue factors, the score exceeding twice SD of the mean of healthy subjects is represented as “high.” For continuous variables, data were expressed per 1 SD to make the variables scale and unit invariant. †, P < 0.01. CI, confidence interval. (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses for the association between high fatigue score and cardiovascular events.

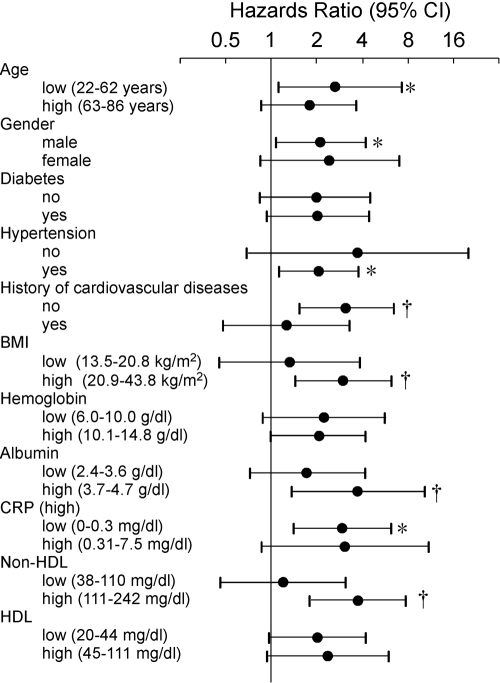

To examine whether the association between fatigue symptoms and occurrence of cardiovascular events was independent of the other potential confounders, multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed. When significant risk factors identified in Figure 1A were used for variables, fatigue score, age, diabetes, and CVD history were all still significantly and independently associated with cardiovascular events (Table 3). Moreover, association of high fatigue score with cardiovascular events was hardly affected, even when it was adjusted for other covariates, including gender, hypertension, BP, BMI, hemoglobin, CRP, albumin, glucose, and non-HDL and HDL cholesterol (data not shown). Comparisons of the risk in key subgroups showed that the risk of high fatigue score for cardiovascular events was more prominent in the subgroups of patients with lower age, no CVD history, higher albumin, and high non-HDL cholesterol (Figure 2). When baseline risk factors were compared between event (−) and (+) subjects (Table 4), classical risk factors, in addition to high fatigue score, were higher in the events (+) group. However, in well-nourished subjects without diabetes and CVD history (n = 338), all classical risk factors did not show significant difference, with prevalence of high fatigue score being still significantly higher in events (+) than events (−) subjects.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox proportional analyses of the factors associated with cardiovascular events

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| High fatigue score | 1.89 (1.06 to 3.36) | 0.029 |

| Age (1 SD) | 1.43 (1.06 to 1.94) | 0.021 |

| Presence of diabetes | 2.62 (1.57 to 4.36) | <0.001 |

| History of CVDs | 2.51 (1.50 to 4.19) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the risk of high fatigue score for cardiovascular events in key subgroups as analyzed by Cox proportional hazard analyses. Age, BMI, hemoglobin, albumin, CRP, non-HDL, and HDL were divided into high and low groups on the basis of the medians. *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01. CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Comparisons of the risk factors at registration between future cardiovascular event-free subjects (−) and subjects in whom cardiovascular events occurred (+)

| CVD(−) | CVD(+) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | |||

| n | 706 | 82 | |

| Male, % | 63.1 | 73.2 | 0.073 |

| Age, yr | 61.4 ± 10.7 | 65.1 ± 9.8 | 0.003 |

| diabetes, % | 22.7 | 48.8 | <0.001 |

| history of CVDs, % | 22.1 | 45.1 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.2 ± 3.2 | 21.4 ± 3.3 | 0.48 |

| albumin, g/dl | 3.66 ± 0.30 | 3.63 ± 0.33 | 0.61 |

| systolic BP, mmHg | 151.9 ± 22.1 | 158.4 ± 21.9 | 0.013 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.3 ± 9.9 | 75.6 ± 9.8 | 0.53 |

| non-HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.93 ± 0.87 | 3.11 ± 0.96 | 0.080 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.20 ± 0.37 | 1.13 ± 0.36 | 0.100 |

| high fatigue score, % | 13.4 | 26.7 | 0.006 |

| Well-nourished subjects (albumin >3.3) without diabetes and history of CVDs | |||

| n | 338 | 15 | |

| male, % | 59.5 | 53.3 | 0.63 |

| age, yr | 60.0 ± 10.9 | 65.5 ± 13.3 | 0.055 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.8 ± 3.2 | 20.6 ± 2.8 | 0.77 |

| systolic BP, mmHg | 149.6 ± 22.3 | 151.5 ± 20.3 | 0.74 |

| diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.3 ± 9.3 | 77.0 ± 9.7 | 0.77 |

| non-HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.90 ± 0.86 | 3.13 ± 0.96 | 0.30 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.23 ± 0.37 | 1.24 ± 0.32 | 0.92 |

| high fatigue score, % | 13.9 | 36.4 | 0.039 |

Well-nourished subjects were determined by serum albumin level higher than 3.3g/dl which was determined as higher than mean minus 1 standard deviation. CVD, events for cardiovascular diseases; HDL, high density lipoprotein.

In the subgroup of patients without the CVD history, Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazard analyses revealed that factors of overwork (hazard ratio 2.52) and autonomic imbalance (hazard ratio 1.96) were also significantly (P < 0.05) associated with occurrence of cardiovascular events (data not shown).

Discussion

Our current results clearly show that fatigue is an important predictor for cardiovascular events in a high-risk population, namely, ESRD patients under hemodialysis treatment. Furthermore, using the fatigue-related 64-item questionnaire, we addressed which of the eight conceptualized fatigue-related factors (fatigue itself, anxiety and depression, loss of attention and memory, pain, overwork, autonomic imbalance, sleep problems, and infection) are important to predict cardiovascular events, and demonstrated that fatigue itself is the strongest predictor.

Patients with ESRD are also reported to have a substantially elevated cardiovascular mortality rate (31), and in this population, cardiovascular risk factors can be classified as either “traditional” or “nontraditional” (32). Importantly, the association of fatigue with cardiovascular events is independent of the traditional risk factors, including age, presence of diabetes, and CVD history. In dialysis patients, malnutrition and inflammation were also identified as “nontraditional” risk factors (32), which are also conceptualized as malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome (33). MIA syndrome is shown to be associated with an exceptionally high mortality rate. Of note, cardiovascular risk of highly fatigued patients is independent of any of the markers for malnutrition (BMI, albumin), inflammation (CRP), and atherosclerosis (CVD history). Moreover, comparisons of the risk of fatigue in key subgroups unveil specific characteristics of the patients whose fatigue is at great risk for cardiovascular events: lower age, no previous CVD, high BMI, high albumin, and high non-HDL cholesterol. These characteristics apparently are exhibited in well-nourished subjects, and they apparently reside outside of the population of MIA syndrome. In our cohort, univariate Cox proportional hazards analyses revealed that important components of MIA syndrome, low albumin, high CRP, and CVD history, were all significantly associated with all-cause mortality (data not shown). Thus, in spite of significant effects on cardiovascular events, the effect of fatigue on total mortality could be overwhelmed by the nutritional and inflammatory problems in dialysis patients, which could be the potential reason why fatigue dimension is related only to cardiovascular events but not to total mortality in our cohort. An explanation may fit to the observation that fatigue is not significantly associated with cardiovascular events in an elderly population (Figure 2). When history of cardiovascular events, BMI, and serum CRP were included as covariates in multivariate Cox analyses, high fatigue score was significantly and independently associated with cardiovascular events in this subgroup (hazard ratio: 2.84; 95% confidence interval: 1.23 to 6.58).

It appears that the fatigue domain in our instrument could represent a dimension distinct from QoL. The coefficients of correlations of our fatigue score with the majorities of the components of KDQoL were not necessarily high. Furthermore, impaired health-related QoL was shown to be closely related to malnutrition and inflammation (34), in sharp contrast to a lack of relationship of the fatigue score in this study. Recent systematic review also revealed that health-related QoL in ESRD was most affected in the physical domains, and nutritional biomarkers are most closely associated with these domains (35). Impaired QoL was shown to be associated with hospitalization and mortality in hemodialysis patients (34,36–38). Very recently, Jhamb et al. (39) showed in a cohort of 917 incident hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients that low vitality scale as measured by SF-36 was associated with inflammation, other low QoL scores, and with poor 1-year survival. Thus, as compared with our fatigue scale, QoL scores including vitality better reflect nutritional and inflammatory status in dialysis patients, which could be related to mortality and hospitalization rather than occurrence of cardiovascular events.

Although this study is the important first step to unveil pathophysiological significance of fatigue symptoms in the occurrence of cardiovascular events, there are many steps forward to be clarified. Can our novel fatigue score predict cardiovascular events in the general population or other patients with disease? Can a quantitative marker for fatigue be a good biomarker to predict cardiovascular events? Can improvement of fatigue lead to decreased morbidity? All of these steps are crucial to highlighting the significance of fatigue as an important piece of risk predictors for CVD in patients with ESRD.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 21st Century COE Program “Base to Overcome Fatigue” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and was partly supported by grants from Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at http://www.cjasn.org/

References

- 1.Gullette EC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak M, Jiang W, Waugh RA, Frid DJ, O'Connor CM, Morris JJ, Krantz DS: Effects of mental stress on myocardial ischemia during daily life. JAMA 277: 1521–1526, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain D, Shaker SM, Burg M, Wackers FJ, Soufer R, Zaret BL: Effects of mental stress on left ventricular and peripheral vascular performance in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 31: 1314–1322, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krantz DS, Sheps DS, Carney RM, Natelson BH: Effects of mental stress in patients with coronary artery disease: Evidence and clinical implications. JAMA 283: 1800–1802, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burg MM, Jain D, Soufer R, Kerns RD, Zaret BL: Role of behavioral and psychological factors in mental stress-induced silent left ventricular dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 22: 440–448, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Mulry RP, Tofler GH, Jacobs SC, Friedman R, Benson H, Muller JE: Triggering of acute myocardial infarction onset by episodes of anger. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. Circulation 92: 1720–1725, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabbay FH, Krantz DS, Kop WJ, Hedges SM, Klein J, Gottdiener JS, Rozanski A: Triggers of myocardial ischemia during daily life in patients with coronary artery disease: Physical and mental activities, anger and smoking. J Am Coll Cardiol 27: 585–592, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang W, Babyak M, Krantz DS, Waugh RA, Coleman RE, Hanson MM, Frid DJ, McNulty S, Morris JJ, O'Connor CM, Blumenthal JA: Mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia and cardiac events. JAMA 275: 1651–1656, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J: Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 156: 745–752, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Babyak MA, Krantz DS, Frid DJ, Coleman RE, Waugh R, Hanson M, Appelbaum M, O'Connor C, Morris JJ: Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. Effects on prognosis and evaluation of mechanisms. Arch Intern Med 157: 2213–2223, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe Y: Preface and mini-review: Fatigue science for human health. In: Fatigue Science for Human Health, edited by Watanabe Y, Evengard B, Natelson BH, Jason LA, Kuratsune H.New York, Springer, 2008, pp V–XI [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, Komaroff AL, Schonberger LB, Straus SE, Jones JF, Dubois RE, Cunningham-Rundles C, Pahwa S, Tosato G, Zegans LS, Purtilo DT, Brown N, Schooley RT, Brus I: Chronic fatigue syndrome: A working case definition. Ann Intern Med 108: 387–389, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A: The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 121: 953–959, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natelson BH: Chronic fatigue syndrome. JAMA 285: 2557–2559, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiyama T, Yoshihara M: New occupational threats to Japanese physicians: Karoshi (death due to overwork) and karojisatsu (suicide due to overwork). Occup Environ Med 65: 428–429, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michie S, Cockcroft A: Overwork can kill. BMJ 312: 921–922, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy SE, Studenski SA: Fatigue predicts mortality in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 1910–1914, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appels A, Mulder P: Excess fatigue as a precursor of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 9: 758–764, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole SR, Kawachi I, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM: Sense of exhaustion and coronary heart disease among college alumni. Am J Cardiol 84: 1401–1405, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott E, Holst C, Gronbaek M, Schnohr P, Jensen G, Barefoot J: Vital exhaustion as a risk factor for ischaemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in a community sample. A prospective study of 4084 men and 5479 women in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Int J Epidemiol 32: 990–997, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP: Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 37: 147–153, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis G, Wessely S: The epidemiology of fatigue: More questions than answers. J Epidemiol Community Health 46: 92–97, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang WK, Hung KY, Huang JW, Wu KD, Tsai TJ: Chronic fatigue in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 21: 479–485, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unruh M, Benz R, Greene T, Yan G, Beddhu S, DeVita M, Dwyer JT, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Martin A, Rehm-McGillicuddy J, Teehan BP, Meyer KB: Effects of hemodialysis dose and membrane flux on health-related quality of life in the HEMO Study. Kidney Int 66: 355–366, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jhamb M, Weisbord SD, Steel JL, Unruh M: Fatigue in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: A review of definitions, measures, and contributing factors. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 353–365, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay RM, Heidenheim PA, Nesrallah G, Garg AX, Suri R: Minutes to recovery after a hemodialysis session: A simple health-related quality of life question that is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 952–959, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, Levenson DJ, Cooksey SH, Fine MJ, Kimmel PL, Arnold RM: Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 960–967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukuda S, Takashima S, Iwase M, Yamaguchi K, Kuratsune H, Watanabe Y: Development and validation of a new fatigue scale for fatigued subjects with and without chronic fatigue syndrome. In: Fatigue Science for Human Health, edited by Watanabe Y, Evengard B, Natelson BH, Jason LA, Kuratsune H.New York, Springer, 2008, pp 89–102 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green J, Fukuhara S, Shinzato T, Miura Y, Wada S, Hays RD, Tabata R, Otsuka H, Takai I, Maeda K, Kurokawa K: Translation, cultural adaptation, and initial reliability and multitrait testing of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument for use in Japan. Qual Life Res 10: 93–100, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindner A, Charra B, Sherrard DJ, Scribner BH: Accelerated atherosclerosis in prolonged maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 290: 697–701, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW: Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 108: 2154–2169, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pecoits-Filho R, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P: The malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome–the heart of the matter. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17[Suppl 11]: 28–31, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rambod M, Bross R, Zitterkoph J, Benner D, Pithia J, Colman S, Kovesdy CP, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of Malnutrition-Inflammation Score with quality of life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: A 5-year prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 298–309, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel BM, Melmed G, Robbins S, Esrailian E: Biomarkers and health-related quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1759–1768, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Block G, Humphreys MH: Association among SF36 quality of life measures and nutrition, hospitalization, and mortality in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2797–2806, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopes AA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Satayathum S, McCullough K, Pifer T, Goodkin DA, Mapes DL, Young EW, Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Port FK: Health-related quality of life and associated outcomes among hemodialysis patients of different ethnicities in the United States: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 41: 605–615, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, McCullough KP, Goodkin DA, Locatelli F, Fukuhara S, Young EW, Kurokawa K, Saito A, Bommer J, Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Port FK: Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Int 64: 339–349, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jhamb M, Argyropoulos C, Steel JL, Plantinga L, Wu AW, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB, Unruh ML; Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study: Correlates and outcomes of fatigue among incident dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1779–1786, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]