Frontal lobe seizures may manifest bizarre behaviors such as thrashing, kicking, genital manipulation, unusual facial expressions, and articulate vocalizations.1 Aggressive and violent behaviors have also been associated with epilepsy, especially temporal or frontal lobe seizures.2 However, this behavior is rare in the ictal state. Aggressive ictal behavior is generally believed to not be goal directed. Interactive behavior with the ability to respond to visual and verbal stimuli is also rare in complex partial seizures. We report the case of a patient with seizures manifesting with interactive directed aggressive behaviors.

Case report.

An 18-year-old right handed man was brought in by his mother for a second opinion regarding possible seizures after being suspended from junior college for threatening to shoot his teacher and classmates. The patient had been born prematurely and had a grade 1 periventricular hemorrhage. Motor milestones were delayed by 4 months, but development was otherwise normal. He had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure at age 9, and subsequently had complex partial seizures characterized by confusion, hand automatisms, and drawing up of the legs. These seizures resolved on carbamazepine, which was discontinued after 2 years. At age 15, the patient started having stereotyped episodes characterized by a feeling of “stage fright” and followed by verbal profanities and using his hand as a stylized gun to “shoot” people and objects. The patient never physically struck another person or object during the episodes. He was not postictally confused, was aware that he had a behavioral change, but was amnestic for details of his behavior. He did not respond to trials of zonisamide, carbamazepine, or topiramate. An outside EEG performed during an episode of coprolalia was interpreted as normal and the patient was given a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS). A psychiatrist diagnosed him with obsessive-compulsive disorder but found no evidence for psychosis, anxiety, or mood disorder. Events increased to up to 40 events daily at time of presentation, despite multiple medication trials to treat TS.

Video-EEG monitoring captured 11 seizures in the awake state and 3 seizures during sleep. All seizures were stereotyped and lasted between 15 and 45 seconds. Three seizures occurred within a 15-minute period in the presence of the attending and resident physician. During these 3 seizures, the patient partially followed simple commands and demonstrated comprehension of spoken language (video 1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org), and struck a nonthreatening hand held 2 feet from him (video 2).

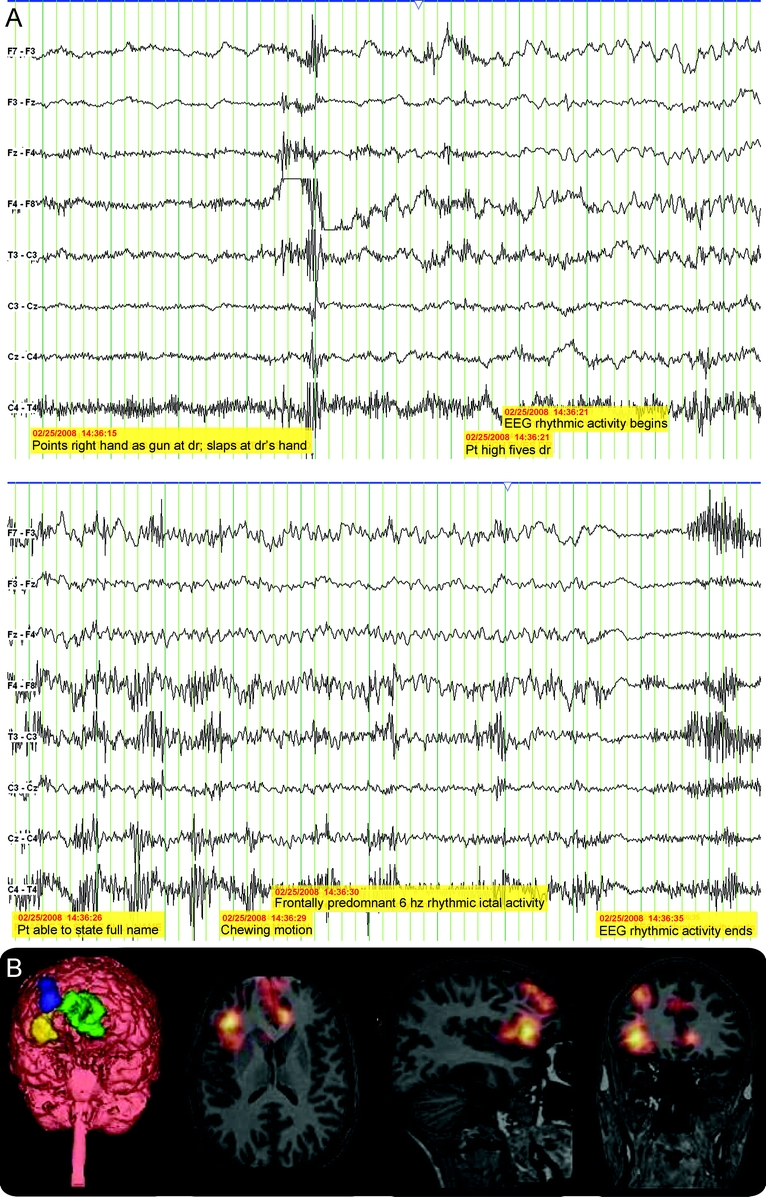

During uninterrupted seizures, the patient would speak profane language with threatened aggression, using his hands as stylized guns to track moving people and “shoot” them (video 3). He appeared to alter his actions in reaction to external visual and verbal stimuli. Lip smacking automatisms were present in the latter half of the seizure. The patient was amnestic for the major portion of his seizures, but could accurately identify the person who questioned him during the seizure (video 4). EEG analysis found bifrontal 5- to 6-Hz rhythmic activity during seizures (figure). Ictal SPECT showed areas of hyperperfusion in the right lateral and orbitofrontal cortex. An area of hyperperfusion is also seen in the left medial frontal lobe.

Figure Ictal EEG and ictal SPECT results

(A) The electrographic ictal changes on a condensed transverse montage during a seizure. (B) Ictal SPECT showed focal regions of hyperperfusion in the right lateral and orbitofrontal cortex and left medial frontal cortex. Ictal SPECT scan performed using Technitium-99 and superimposed upon interictal SPECT scan and coregistered to MRI (SISCOM).

Carbatrol® was instituted at a daily divided dose of 900 mg. His previous highest daily dose of carbamazepine was 600 mg. The patient is seizure-free at 12 months follow-up.

Discussion.

More so than seizures arising from other brain locations, frontal lobe seizures may exhibit bizarre and unusual behaviors.3 It is generally agreed among neurologists and epileptologists that well-organized, purposeful, complex, goal-directed behavior is highly unlikely during a seizure.4,5 Our patient is an unusual case demonstrating ictal aggressive behavior with complex motor and vocal features that could be misinterpreted as goal-directed actions. While up to 30% of frontal lobe epilepsy patients have articulate vocalizations including swearing,2 our patient’s seemingly voluntary actions are likely involuntary, representing complex gestural-hyperkinetic automatisms and vocalizations. The pathophysiology of this behavior is likely related to activation of circuitry in the primary somatomotor and premotor cortex by epileptic activity.6,7 The florid emotional outburst and aggressive behavior could localize to the prefrontal cortex, considered to be connected with higher psychic functions, as well as limbic regions involvement. The fact that he is partially amnestic to the ictal events points toward a complex partial event with possible spread to mesial temporal structures.

This study demonstrates a rare case of directed and interactive aggressive verbal and physical behavior during frontal lobe seizures. This case highlights the potential for certain frontal lobe seizures to cause behavior with significant adverse legal ramifications. The diagnosis of seizures should always be considered in cases of episodic stereotyped behavior.

Supplementary Material

Editorial, page 1720

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

e-Pub ahead of print on October 21, 2009, at www.neurology.org.

Disclosure: Dr. Shih serves as a consultant to URL Pharma, Inc., and receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, NeuroPace, Inc., Eisai Inc., the NIH (ad hoc study section reviewer), and the National Science Foundation. Dr. LeslieMazwi, Dr. Falcao, and Dr. Van Gerpen report no disclosures.

Received March 21, 2009. Accepted in final form July 22, 2009.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. J.J. Shih, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL 32224; Shih.jerry@mayo.edu

&NA;

- 1.Williamson PD, Spencer DD, Spencer SS, Novelly RA, Mattson RH. Complex partial seizures of frontal lobe origin. Ann Neurol 1985;18:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jobst BC, Seigel AM, Thadani VM, Roberts DW, Rhodes HC, Williamson PD. Intractable seizures of frontal lobe origin: clinical characteristics, localizing signs, and results of surgery. Epilepsia 2000;41:1139–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manford M, Fish DR, Shovron SD. An analysis of clinical seizure patterns and their localizing value in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Brain 1996;119:17–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh L, Krauss GL. Aggression and violence in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2000;1:160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez MF. Postictal violence and epilepsy. Psychosomatics 1998;39:478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain Cogn 2004;56:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasselmo ME. A model of prefrontal cortical mechanisms for goal-directed behavior. J Cogn Neurosci 2005;17:1115–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.