Abstract

Background

Depression and antidepressant use are common in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the effect of antidepressant treatment for depression on longer-term outcomes is unknown. We report the week-24 outcomes of patients who participated in a 12-week efficacy study of sertraline for depression of AD.

Methods

131 participants (sertraline=67, placebo=64) with mild-moderate AD and depression participated in the study. Patients who showed improvement on the modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression-Change (mADCS-CGIC) after 12 weeks of randomized treatment with sertraline or placebo continued double-blinded treatment for an additional 12 weeks. Depression response and remission at 24 weeks were based on mADCS-CGIC score and change in Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) score. Secondary outcome measures included time to remission, non-mood neuropsychiatric symptoms, global cognition, function, and quality of life.

Results

117 (89.3%) participants completed all study assessments and 74 (56.5%; sertraline=38, placebo=36) completed all 24 weeks on randomized treatment. By 24 weeks, there were no between-group differences in depression response (sertraline=44.8%, placebo=35.9%; odds ratio [95% CI]=1.23 [0.64, 2.35]), change in CSDD score (median difference=0.6 [95% CI −2.26, 3.46], χ2 [df=2]=1.03), remission rates (sertraline=32.8%, placebo=21.8%; odds ratio [95% CI]=1.61 [0.70, 3.68]), or secondary outcomes. Common SSRI-associated adverse events, specifically diarrhea, dizziness, and dry mouth, and pulmonary serious adverse events (SAEs) were more frequent in sertraline-randomized patients than in placebo subjects.

Conclusions

Sertraline treatment is not associated with delayed improvement between 12 and 24 weeks of treatment and may not be indicated for the treatment of depression of AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is classified as a cognitive disorder, but neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in AD are common and associated with worse quality of life (QoL) and increased caregiver burden(1-3). Depression occurs in up to 50% of AD patients and is often chronic(4). Antidepressant use is common in dementia, with one recent study reporting use in almost half of patients(5). However, evidence for antidepressant efficacy in this population is limited, and published controlled trials report equivocal results(6-12). Because depression in AD is a source of distress to patients and caregivers, there is a need for efficacious and well-tolerated antidepressants in these patients.

Given this unmet need, we conducted a multicenter, 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled antidepressant trial of sertraline for depression of AD (dAD) titled “Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease-2” (DIADS-2)(13). In this study, sertraline was not efficacious for the treatment of dAD in the short-term(14).

After the 12-week efficacy trial, the study included an additional 12-week extension phase (total duration of 24 weeks) of randomized treatment for at least partial responders during the acute phase and, for ethical reasons, the option for open-label treatment for non-responders (13). The objective of this extended period was to investigate any delayed benefits of sertraline treatment that would have been the result of sustained depression reduction. In addition to mood outcomes over the 24-week period, secondary outcomes during the extension phase included non-mood NPS, global cognition, function and quality of life (QoL). Week-24 results, presented here, compare patients by baseline randomization during the second phase of the study. We hypothesized that, compared with placebo treatment, sertraline treatment would be associated with improvements over 12 to 24 weeks in mood and secondary outcome measures.

Methods

Subjects

Details of the study design have been published(13). Briefly, participants: (1) were recruited from five memory disorder clinics in the United States; (2) met criteria for Dementia due to AD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)(15) criteria; (3) had Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)(16) scores of 10–26, inclusive; and (4) met criteria for depression of AD(17,18). Depression of AD (dAD) criteria differ from the DSM-IV-TR(15) criteria for major depressive episode in requiring the presence of 3 (as opposed to 5) or more total symptoms, not requiring that gateway symptoms be present “most of the day, nearly every day”, distinguishing social isolation or withdrawal from anhedonia, and adding irritability as a symptom. Stable cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine treatments were allowed, but antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines were not. Anticonvulsants were allowed only for treatment of a pre-existing seizure disorder.

Consent was obtained from participants and their authorized representatives using procedures established by individual sites and their Institutional Review Boards(19). Informed consent also was obtained from caregivers for the collection of caregiver measures. The study was conducted under the oversight of a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) operated by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

12-week efficacy study

After baseline assessment, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive sertraline or placebo. The randomization schedule was generated in permuted blocks stratified by the 5 clinical sites, as it was anticipated that there would be between-site differences in demographic and clinical characteristics Initial treatment was with 50 mg sertraline (or identically-appearing placebo tablets) daily. After one week, the dosage was increased to the target of 100 mg sertraline daily (or placebo). During the first four weeks post-randomization, clinicians had the option of increasing or decreasing the daily dose depending on response and tolerability. Caregivers received a standardized psychosocial intervention that consisted of 20-30 minute counseling sessions at every study visit (with phone sessions between visits if needed), were provided educational materials, and had 24-hour access to crisis management(13). In-person visits occurred at baseline and 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-randomization.

At each study visit, based on patient examination and caregiver interview, clinicians rated overall impression of clinical change from baseline using the modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change index (mADCS-CGIC), which in addition to the original scale(20) incorporates a global rating of mood and associated symptoms of depression. The mADCS-CGIC uses a seven-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (“much better”) to 7 (“much worse”), with a score of 4 being “no change”.

12-week extension phase (weeks 13-24 post randomization)

At week 12, patients rated as having improved at least minimally (i.e., scores of 1, 2 or 3) continued on their randomized, blinded study treatment. Patients rated as unchanged or worse overall had the option of discontinuing randomized treatment and utilizing any open-label treatment. Regardless of randomization or treatment status during the extension phase, and while still blinded to treatment assignment, participants were encouraged to continue study participation and complete all study assessments. Visits for the extension phase occurred at 16, 20, and 24 weeks post-randomization.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was depression response based on the mADCS-CGIC score, defined as a score of 1 or 2. Change in severity of depression over time was assessed with the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD)(21), a 19-item scale (scores 0-38, higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms) measuring severity of depression in dementia, utilizing input from both the caregiver and the subject. Remission was defined a priori by a combination of mADCS-CGIC score ≤2 and CSDD score ≤6. For additional analyses, “first remission” was defined as the first week the participant met the definition of remission, and “sustained remission” was defined as the first week when the participant met the definition of the remission for all remaining weeks of the trial.

Other outcomes included: global cognition (MMSE score), non-mood neuropsychiatric symptoms (the seven non-mood items of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)(22) [delusions, hallucinations, agitation, elation, apathy, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior]), function (the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Scale [ADCS-ADL](23)), and quality of life (the Alzheimer’s Disease Related Quality of Life Scale [ADRQL](24)).

To monitor for adverse events, a symptom checklist derived from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved prescribing information for sertraline was assessed as follows: Starting at baseline and at all follow-up in person visits, participants and their caregivers were asked about whether any of these symptoms, or other self-reported adverse effects (AEs), occurred within the last month (at baseline) or since the last study visit. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented as defined by the FDA(25).

Analysis

All analyses were intention-to-treat and performed according to patients’ original treatment assignments (i.e. randomization to sertraline or placebo). Missing outcomes were imputed using the method of multiple imputation(26). Prediction models of the missing data were estimated based on the patients’ other available baseline and follow-up data, and these models were used to impute the missing outcomes five times. The results of five imputations were synthesized using simple combination rules(27) to yield estimates of treatment comparisons.

The primary measure of mood response compared the ratings of the two groups at week 24 on the mood domain of the mADCS-CGIC, assessed by proportional odds logistic regression. Mixed effects models were used to compare treatment groups over the 24 weeks for the continuous outcomes CSDD, NPI (non-mood), MMSE, ADCS-ADL, and ADRQL. The mixed models included a random intercept and slope for each patient. Transformations of the outcomes were used when needed (i.e., when the outcome was not normally distributed). Polynomial changes in the outcomes over time were allowed when needed. To test for different rates of change in these continuous outcomes over time, a likelihood ratio test was used to compare a model allowing the changes over time to differ by treatment group to a model that did not allow the changes over time to differ by treatment group. The medians of the CSDD scores were compared at each visit. Standard errors of medians were calculated by bootstrapping. To compare remission rates, the proportion of patients in each treatment group whose depression remitted at week 24 was compared using logistic regression. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to calculate between-group differences in time to first and sustained remission. The analyses were evaluated for outliers, and the distributional assumptions of the models were confirmed.

Since years of education differed by treatment group, the results include adjustment for years of formal education. Models with and without adjustment for site were analyzed; the treatment effect estimates were virtually identical, so the results reported here are from the models without controlling for site.

Exact tests were used to compare the number of patients experiencing all-cause and specific-cause AEs and SAEs in the two treatment groups.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 2.7.1(28). All p-values are two-sided. p<.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Variables

131 patients met eligibility criteria and underwent randomization (sertraline=67, placebo=64)(14). At study entry participants had a median age of 79 years. Fifty four percent were female; 67% were non-Hispanic white, 21% African-American, and 11% Hispanic/Latino. Participants randomized to sertraline had more years of formal education than those in the placebo group. Baseline MMSE and CSDD scores reflected mild-moderate dementia severity and a moderately depressed group, with approximately 40% of subjects meeting criteria for major depressive episode.

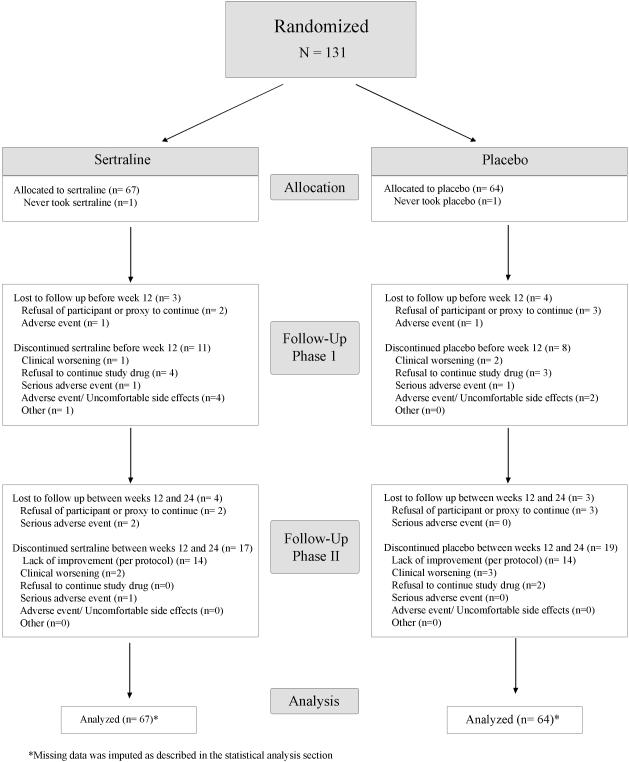

Subject Retention

Participant flow through the trial is described in Figure 1. Seven (sertraline=3, placebo=4) subjects were lost to follow-up during the acute study phase, so 64 (95.5%) sertraline-randomized and 60 (93.8%) placebo-randomized patients entered the extension phase. Seven subjects (sertraline=4, placebo=3) discontinued study participation during the extension phase. Thus, 117 (89.3%) of all randomized participants completed the week-24 assessment.

Figure 1.

CONSORT chart of patient flow in DIADS-2

Including those participants who were lost to follow-up, 21 (sertraline=12, placebo=9) participants either never took (N=2) or discontinued (N=19) study medication prior to week 12. An additional 14 sertraline patients and 14 placebo patients discontinued randomized treatment at the end of week 12 based on non-response, thus 41 (61.2%) sertraline patients and 41 (64.1%) placebo patients remained on randomized treatment at the beginning of the extension phase.

During the extension phase, an additional 8 participants (sertraline=3, placebo=5) discontinued randomized treatment. A total of 74 (sertraline=38, placebo=36) patients, or 56.5% of the original study population, completed 24 weeks on their randomized treatment.

Mood Outcomes

There were no between-group differences in mADCS-CGIC scores at week 24 (proportional odds logistic regression ORsertraline = 1.23, 95% CI (0.64, 2.35), Wald χ2 = 0.37 with 1 df, p=0.54), with 44.8% of sertraline-treated and 35.9% of placebo-treated patients rated as responders (Table 1).

Table 1. Modified ADCS – Clinical Global Impression of Change (mADCS-CGIC) at week 24.

| CGIC Rating | Sertraline (N=67) |

Placebo (N=64) |

|---|---|---|

| 7 (“much worse”) | 1 | 2 |

| 6 (“worse”) | 0 | 3 |

| 5 (“a bit worse”) | 12 | 8 |

| 4 (“no change”) | 5 | 10 |

| 3 (“a bit better”) | 19 | 18 |

| 2 (“better”) | 18 | 15 |

| 1 (“much better”) | 12 | 8 |

Proportional odds regression (combination of all 5 imputations): Odds ratio (95% CI) sertraline: 1.23 (0.64, 2.35), p=0.54. The data displayed are from the first imputation.

Likewise, there was no between-group differences in CSDD scores at week 24, with the difference in the medians (95% CI) (placebo – sertraline) being 0.60 (−2.26, 3.46) (Table 2). Moreover, there was no treatment effect on the change in CSDD over time (i.e., the model including terms for treatment group by time interactions was not superior to the model without these interaction terms [likelihood ratio χ2 =0.26, df=3, p=0.97]).

Table 2. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) difference by visit (median [95% CI*] difference for placebo – sertraline).

| Week 2 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 12 | Week 16 | Week 20 | Week 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.80 (−1.63, 3.23) |

0.80 (−1.75, 3.35) |

1.20 (−1.18, 3.58) |

1.20 (−1.65, 4.05) |

1.60 (−0.90, 4.10) |

0.40 (−2.99, 3.79) |

0.60 (−2.26, 3.46) |

Standard errors for medians calculated by bootstrapping. The results from all five imputations were combined.

There was no statistically significant difference in the estimated odds of remission on sertraline treatment compared with placebo, with 32.8% of sertraline-treated and 21.8% of placebo-treated patients rated as remitted at week 24 (logistic regression ORsertraline = 1.61 95% CI (0.70, 3.68), Wald χ2 = 1.28 with 1 df, p=0.26). Likewise, there were no between-group differences in time to first remission (HRsertraline = 1.13, 95% CI (0.58, 2.18), Wald χ2 = 0.14 with 1 df, p=0.71) or time to sustained remission (HRsertraline = 1.90, 95% CI (0.93, 3.88), Wald χ2 = 3.13 with 1 df, p=0.08).

Non-Mood Outcome Measures

There was improvement over the course of 24 weeks overall in neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life, but change over time in these outcomes did not differ by treatment group (Table 3). There was no improvement (or worsening) over time in activities of daily living or global cognition in the overall study sample.

Table 3. Non-Mood Outcome Measures at Week 24&.

| Measure | Baseline | Week 24 | Treatment Effect* (χ2[df], p value) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sertraline | Placebo | Sertraline | Placebo | ||

| NPI Non-Mood | 10 (5, 19) | 9.5 (3.75, 14) | 6 (2, 11) | 4 (0, 12) | χ2=7.9 (4), 0.10 |

| ADRQL | 81.7 (72.8, 88.5) | 81.1 (73.2, 88.4) | 87.1 (80.4, 92.2) | 85.7 (73.3, 92.5) | χ2=0.9 (2), 0.30 |

| ADCS-ADL | 55 (44.5, 66.5) | 56.5 (47.75, 66) | 56 (41.5, 66) | 53.5 (34, 67) | χ2<0.001 (1), 0.99 |

| MMSE | 21 (17, 25) | 19.5 (15, 23.25) | 21 (16.5, 24) | 20 (14.75, 24) | χ2= 0.5 (1),0.50 |

The table shows the median (1st, 3rd quartiles) of the data from the first imputation

Likelihood ratio statistic using data from all study visits comparing a model including interaction terms for treatment group by time variables versus a model without these interaction terms.

Safety and Tolerability

Several SSRI-associated AEs, including diarrhea, dizziness, and dry mouth, were more common over the 24-week period in participants randomized to sertraline compared to placebo-randomized participants (Table 4).

Table 4. Cumulative Frequency of Adverse Events at 24 Weeks.

| Adverse Event |

Placebo (N=66*) |

Sertraline (N=63*) |

Sertraline vs. Placebo (Unadjusted)& |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value (exact) |

|||

| Diarrhea | 22 (33%) | 36 (57%) | 2.22 | (1.04, 4.76) | 0.03 |

| Dizziness | 26 (39%) | 44 (70%) | 2.86 | (1.31, 6.25) | 0.005 |

| Dry mouth | 23 (35%) | 37 (59%) | 2.22 | (1.03, 4.76) | 0.03 |

Fisher’s exact test

Subjects with adverse event data available

Over 24-weeks, SAEs occurred in 27.3% of sertraline patients, compared with 12.7% of placebo patients (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.05). During the extension phase, 10.6% of patients randomized to sertraline experienced an SAE, compared with 1.6% of placebo patients. Examining specific SAEs, 12.1% of sertraline-randomized patients had a pulmonary SAE over 24 weeks, including 6.1% during the extension phase, compared with no placebo patients (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.006). The diagnoses for the pulmonary SAEs were infections (N=6), pneumothorax (N=1), and pulmonary embolism (N=1).

Discussion

Sertraline treatment is not associated with long-term improvements in mood outcomes and did not lead to any long-term benefit in non-mood neuropsychiatric symptoms, function, quality of life, or global cognition when dAD criteria were used to specify the presence of depression.

Although there was no antidepressant treatment effect, there was significant improvement for the entire study sample in mood, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and quality of life. For instance, 41% of all patients met response criteria and CSDD scores decreased on average by approximately 50% at week 24. This effect over time, in the context of a nearly 90% completion rate, suggests either non-specific therapeutic effects for being in this trial or that a substantial proportion of depressed AD patients improve with time. Including a structured psychosocial intervention for caregivers in both treatment groups may have contributed to this effect, although the response rate in the placebo group was similar to that reported in other AD antidepressant studies without such an intervention(8,11,12).

Most of the improvements in mood occurred during the first 12 weeks. Among sertraline-randomized patients, the mADCS-CGIC response rate was 40% at week 12 and 45% at week 24, and remission rates were 33% at both time points. Thus there appeared little benefit overall from an additional 12 weeks of participation in the trial even though non-responders were eligible for open-label treatment during the extension phase of the study.

As studies have shown an association between depression in AD and other NPS(2), decreased function(29), and worse quality of life(30), we examined whether antidepressant treatment might have a longer-term impact on any of these outcome measures. Given that patients randomized to sertraline did not have improved mood outcomes compared with placebo-randomized patients after 24 weeks, it is not surprising that sertraline treatment was not associated with improvements in these secondary outcome measures.

Acute sertraline treatment was not associated with greater impairments in global cognition at 24 weeks as assessed by the MMSE. This is consistent with the results of a metaanalysis of short-term efficacy trials for depression in AD(31), and a retrospective study of long-term antidepressant (primarily SSRI) treatment in AD(32). Cognitive effects might be discernable, however, on more detailed neuropsychological tests(13).

The majority of sertraline-treated patients experienced diarrhea, dizziness, and dry mouth, with a 2-3 increased odds ratio. In addition, SAEs, specifically pulmonary SAEs, were more common in sertraline-randomized patients compared with placebo subjects and is consistent with a prior study(33). Although a case-control study suggested that the risk of hospitalization for either pneumonia in general or aspiration pneumonia specifically was a confounded observation(34), the finding here is an unbiased estimate supporting the previous observation. Overall, sertraline treatment cannot be considered to have a benign adverse event profile in AD patients.

The results of this study add to the SSRI treatment literature for depression in AD that has had as many negative as positive studies (8,10-12). While one may consider the possibility that this clinical trial enrolled patients with chronic, treatment-resistant depression, three-quarters of study participants had no previous history of a depressive episode. SSRIs may be beneficial for the treatment of other NPS such as agitation in hospitalized AD patients(35), warranting further study. Overall, our findings of lack of efficacy and increased adverse events combined with existing literature lead us to conclude that SSRIs cannot be recommended for the treatment of dAD. Given that depression in AD is common and associated with a range of negative outcomes, there remains an urgent need for efficacious and effective treatments for this condition.

Acknowledgements

Grant funding: National Institute of Mental Health, 1U01MH066136, 1U01MH068014, 1U01MH066174, 1U01MH066175, 1U01MH066176, 1U01MH066177.

Funding

Grants from National Institute of Mental Health, 1U01MH066136, 1U01MH068014, 1U01MH066174, 1U01MH066175, 1U01MH066176, 1U01MH066177.

Role of the funding source

NIMH scientific collaborators participated on the trial’s Steering Committee. Sertraline and matching placebo were provided by Pfizer, Inc., which did not otherwise participate in the design or conduct of the trial. After database lock and study unblinding, the corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All co-investigators had access to the raw data.

Roles of Authors and Contributors

All authors participated in data collection and revision of the paper. Initial drafting of the paper was done by DW. Data analyses were performed by LTD, CF, BKM, CLM.

Trial Registration: NCT00086138

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

These disclosures refer to the period between 7/1/02 and 10/31/08, and include any anticipated conflicts through 12/31/09, according to the DIADS-2 Conflict of Interest Policy (available upon request from the study PI).

- Barbara K. Martin is involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug.

- Paul B. Rosenberg has received research funds from Pfizer, Elan, Lilly and Merck in amounts greater than $10,000.

- Jacobo Mintzer has received research support from Abbot to study donepezil and divalproex sodium, from AstraZeneca to study quetiapine, from BMS to study aripiprazole, from Eli Lilly to study olanzapine, from Forest to study both citalopram and memantine, from Janssen to study galantamine and risperidone, and from Pfizer to study donepezil and memantine; Dr. Mintzer also has been a consultant, paid directly or indirectly, for AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Forest, and Aventis. He also has been an unpaid consultant for Targacept and has participated in Speaker’s Bureaus for Janssen, Forest, and Pfizer.

- Daniel Weintraub has received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim; Dr. Weintraub also has been a paid consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Osmotica Pharmaceutical, BrainCells Inc., EMD Serono, and Sanofi Aventis, and has participated on a Speaker’s Bureau for Pfizer.

- Anton P. Porsteinsson is involved in research sponsored by Pfizer to study donepezil and PF04494700, Eli Lilly to study atomoxetine, a gamma-secretase inhibitor and a beta amyloid antibody, Wyeth to study a beta amyloid antibody, GSK to study a PPAR inhibitor and Forest to study memantine and neramexane; Dr. Porsteinsson has been a paid consultant and participated on a Speaker’s Bureau for Pfizer and Forest.

- Lon S. Schneider is involved in research sponsored by Pfizer; Dr. Schneider has been a paid consultant for Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck, and Wyeth.

- Constantine Frangakis has no conflict of interests.

- Lea T. Drye has no conflict of interests.

- Peter V. Rabins has participated on Speaker’s Bureaus for Wyeth, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

- Cynthia A. Munro has no conflict of interests.

- Curtis L. Meinert is involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug; Dr. Meinert owns shares of GSK stock.

- Constantine G. Lyketsos was involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug; he also was involved in research sponsored by Forest to study escitalopram and citalopram and Pfizer to study sertraline and donepezil; Dr. Lyketsos served as a consultant for Organon, Eisai, GSK, Lilly, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, et al. Point and 5-year prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;23(2):170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard J-ME, Steinberg M, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer disease clusters into three groups: the Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/gps.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garre-Olmo J, Lopez-Pousa S, Vilalta-Franch J, et al. Carer’s burden and depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurol. 2002;34(7):601–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, et al. The persistence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:19–26. doi: 10.1002/gps.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessing LV, Harhoff M, Andersen PK. Treatment with antidepressants in patients with dementia--a nationwide register-based study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(5):902–913. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petracca G, Teson A, Chemerinski E, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of clomipramine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8(3):270–275. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth M, Mountjoy CQ, Amrein R. Moclobemide in elderly patients with cognitive decline and depression: an international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(2):149–157. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, et al. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:737–746. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reifler BV, Teri L, Raskind M, et al. Double-blind trial of imipramine in Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(1):45–49. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyth AL, Gottfries CG. The clinical efficacy of citalopram in treatment of emotional disturbances in dementia disorders: a Nordic multicentre study. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:894–901. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petracca GM, Chemerinski E, Starkstein SE. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13(2):233–240. doi: 10.1017/s104161020100761x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magai C, Kennedy G, Cohen CI, et al. A controlled clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression in nursing home patients with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8(1):66–74. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin BK, Frangakis CE, Rosenberg PB, et al. Design of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Study-2. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:920–930. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000240977.71305.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, et al. Sertaline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:196–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression in Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:129–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzheimer’s Association: Research consent for cognitively impaired adults: recommendations for institutional review boards and investigators. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(3):171–175. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000137520.23370.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider L, Olin J, Doody R, et al. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer’s Disease cooperative study - clinical global impression of change. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;11(suppl 2):S22–S33. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(2 Suppl):33S–39S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabins PV, Kasper JD, Kleinman L, et al. Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 1999;5:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration, Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Section 310, Part D. 2008.

- 26.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 28.R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Stastical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espiritu DAV, Rashid H, Mast BT, et al. Depression, cognitive impairment and function in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1098–1103. doi: 10.1002/gps.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson S, Herrmann N, Rapoport MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for treatment of depression in Alzheimer’s disease: a metaanalysis. Can J Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;52:248–255. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caballero J, Hitchcock M, Beversforf D, et al. Long-term effects of antidepressants on cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31:593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haro M, Rubio M, Xifre B, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia associated to sertraline. Med Clin (Barc) 2002;119(16):637–638. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(02)73522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Leonard CE, et al. Observed association between antidepressant use and pneumonia risk was confounded by comorbidity measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:460–465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]