Abstract

Study Objectives:

Describe the severity of getting to sleep, nighttime awakening, and early morning awakening across the menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause (PM) and their relationship to age, menopausal transition factors, symptoms, stress-related factors, and health related factors.

Design:

Cohort

Setting:

community

Participants:

286 women from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study cohort

Measurements:

Participants completed annual menstrual calendars for MT staging, diaries in which they rated their symptoms, stress levels, and perceived health multiple times per year from 1990-2007 and provided first morning urine samples assayed for E1G, FSH, cortisol, and catecholamines. Multilevel modeling (R program) was used for data analysis.

Results:

Severity of self-reported problems going to sleep was associated with all symptoms, perceived stress, history of sexual abuse, perceived health (-), alcohol use (-) (all P < 0.001), and lower cortisol (P = 0.009), but not E1G or FSH. Severity of nighttime awakening was significantly associated with age, late MT stage. and early PM, FSH, E1G (-), hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain, backache, perceived stress, history of sexual abuse, perceived health (-), and alcohol use (-) (all P < 0.001, except E1G for which P = 0.030). Severity of early morning awakening was significantly associated with age, hot flashes, depressed mood anxiety, joint pain, backache, perceived stress, history of sexual abuse, perceived health (-) (all P ≤ 0.001, except E1G for which P = 0.02 and epinephrine (P = 0.038), but not MT stages or FSH. Multivariate models for each symptom included hot flashes, depressed mood, and perceived health.

Conclusion:

Sleep symptoms during the MT may be amenable to symptom management strategies that take into account the symptom clusters and promote women's general health rather than focusing only on the MT.

Citation:

Woods NF; Mitchell ES. Sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the seattle midlife women's health study. SLEEP 2010;33(4):539-549.

Keywords: Menopausal transition, night time awakening, early morning awakening, sleep onset latency

DURING THE MENOPAUSAL TRANSITION (MT) AND EARLY POSTMENOPAUSE (PM) WOMEN RATE SLEEP PROBLEMS AS AMONG THE MOST PREVALENT AND bothersome of their symptoms. Indeed, nearly 40% of more than 16,000 U.S. participants in the Study of Women and Health Across the Nation (SWAN) reported sleep problems at the baseline interview,1 and nearly 40% of participants in the Melbourne Midlife Women's Health Project reported being bothered by trouble sleeping during the late perimenopause and about 50% during the early postmenopause.2

Shaver and colleagues' early polysomnographic (PSG) studies of midlife women were among the first to demonstrate that sleep symptoms were linked to hot flashes.3 Women who experienced hot flashes during the MT and PM had lower sleep efficiencies (ratio of time asleep to time in bed) and longer REM latency than those without hot flashes. In subsequent studies Shaver and associates found that women who had poor sleep by both self-report and by sleep efficiency criteria scored highest on symptoms such as hot flashes and somatization and had significantly higher morning urinary cortisol levels than the other groups. Women who perceived poor sleep but were classified as good sleepers by the sleep efficiency index scored highest in psychological distress.4,5 These results suggested that in midlife women cognitive or emotional arousal and chronic stress neuroendocrine activation were important in chronic sleep problems.6 Moreover, women with poor sleep reported a higher incidence of somatic symptoms, including musculoskeletal discomfort and fatigue, than those with good sleep.7

More recent studies of the menopausal transition and early postmenopause and sleep have used both subjective and objective measures of sleep to understand its relationship to the MT. The SWAN study participants reported the number of nights over the previous 2 weeks they had difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, and experienced early morning awakening at the beginning of the study and for 7 years of follow-up. Difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep increased through the menopausal transition, particularly during the late menopausal transition, but early morning awakening decreased from late menopausal transition to early postmenopause. Vasomotor symptoms were significantly associated with each of the sleep symptoms and lower estradiol levels and higher FSH levels were each associated with trouble falling asleep and awakening during the night. Hormone therapy use was associated with less sleep disruption. Ethnicity was associated with both waking up several times during the night and early morning awakening, with Caucasian women having the highest incidence.8 In addition, data were obtained from 365 women from SWAN over 2 nights by polysomnographic monitoring in their homes and by response to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Women with greater increases in FSH had more delta sleep, more total sleep time, and less favorable PSQI scores. Higher estradiol levels were modestly associated with better sleep quality; lower estradiol to testosterone (E-to-T) ratio, indicating a higher influence of androgen, was associated with less awakening after sleep onset.9

Penn Ovarian Aging study participants responded to the St. Mary's Hospital Sleep Questionnaire annually over an 8-year period of follow-up. Hot flashes, CESD depression scores, and inhibin B levels were all associated with reduced sleep quality,10 consistent with absence of MT effects seen in earlier analyses of sleep symptoms in this population.11 Sleep was measured with actigraphy and self-report (Insomnia Severity Index) in the Chinese Herbs in Menopausal Symptoms Study (CHIMES).12 Women with moderate to severe hot flashes had ISI scores indicating more problems (> 14). Hot flashes were associated with greater nighttime wakefulness, higher number of long wake episodes, but not sleep efficiency, total sleep time, or sleep latency.

To date the studies of sleep during the MT and early PM show mixed effects of progression through the menopausal transition which may be attributable to lack of attention to staging reproductive aging.13 The Staging Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) and subsequent work by the ReSTAGE collaboration provided specific criteria for determining stages of the menopausal transition (for example, early transition and late transition as described in the methods section of this paper). Endocrine markers for the MT, such as FSH, estradiol, and inhibin B levels have been unmeasured in some studies, but others suggest there may be a relationship between estradiol and FSH and sleep problems during the MT and early PM.8–10

Stressful social environments are common in the lives of midlife women,14 but few investigators have assessed the influence of stressful events, perceived stress, and stress arousal indicators, such as cortisol and catecholamines. Those investigators who have done so, such as Shaver and colleagues, have provided evidence of a link between stress arousal and sleep symptoms with a potential relationship between stress exposure and sleep mediated by cortisol and catecholamines.6

Health status changes are common in midlife and perceived health has been associated with sleep problems.15 To date, health status has been measured in studies such as SWAN, but its relationship to sleep has not been analyzed and reported. There is evidence that the MT presents women with opportunities to change their health behaviors, e.g., by increasing physical activity,16 and these, in turn, may enhance sleep. With the exception of Freedman and Roehr's efforts to identify primary sleep disorders among women in the age group experiencing the menopausal transition,17 there has been little attention to the effects of health status and health behaviors on sleep during the MT and early PM.

Finally, symptoms such as hot flashes have been associated with sleep symptoms, including awakening during the night. Freedman's laboratory study revealed that hot flashes as measured by skin temperature monitoring followed arousals from sleep measured by polysomnography,17 challenging the prevalent view with evidence that sleep changes preceded hot flashes. Freedman's data are consistent with a model of generalized arousal which may play an important role in both hot flashes and sleep symptoms during the MT and may be explained by Shaver's early findings of neuroendocrine arousal and sleep symptoms.6 Moreover, using time series analysis to study a small subgroup of Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study participants, we found that sleep symptoms figured prominently in association with hot flashes, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, and lower sexual desire.18

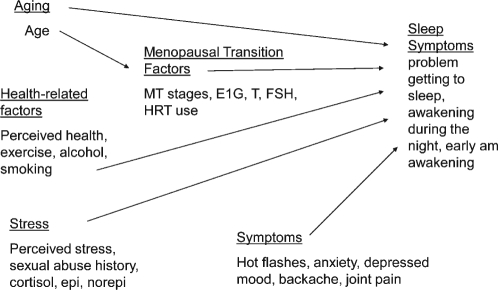

Although research about women's problems with sleep during the menopausal transition has grown over the past two decades, there are few longitudinal reports of sleep symptoms; to date, few of those have addressed sleep in the context of other symptoms, stress, health changes, and health practices that women experience during that period of their lives. Given the complexity and cost of conducting longitudinal studies, few investigators managed to study women more frequently than annually or semi-annually, and very few have used repeated physiologic indicators, such as endocrine assays and polysomnographic recordings. An understanding of the biological changes associated with the menopausal transition, the stressful social context for women during midlife, factors that make women vulnerable to symptoms, changes in health status, and symptoms other than sleep disruption that women experience during this portion of the lifespan is essential for development of appropriate symptom management strategies (see Figure 1 for a preliminary model).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause

The purposes of the analyses presented here are to: (1) describe the severity of nighttime awakening, early morning awakening, and difficulty getting to sleep over time with particular reference to the menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause (PM); and (2) explore the relationship of sleep symptoms to aging, menopausal transition factors (menstrual transition stages, urinary estrogen (EIG), testosterone (T) and FSH levels; hormone therapy use); stress (perceived stress, morning urinary cortisol and catecholamine levels, history of sexual abuse); health related factors (perceived health, exercise, alcohol, and smoking); and symptoms (hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain, and backache).

METHODS

Design

The data for these analyses are from a longitudinal study of the menopausal transition, the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Women entered the cohort between 1990 and early 1992, when most were not yet in the MT or were in the early stages of the transition to menopause. After completing an initial in-person interview (n = 508) administered by a trained registered nurse interviewer, participants (n = 367) began providing data annually by questionnaire, menstrual calendar, and health diary. The health diary included a symptom checklist as well as indicators of health behaviors and stress. Diary data were obtained from the 3 consecutive days closest to days 5, 6, and 7 of the menstrual cycle and coincided with first morning voided urine specimens (collected on day 6) that women provided 8 to 12 times per year for endocrine assays (from late 1996 through 2000), and then quarterly for 2001-2005. These data were in addition to an annual health questionnaire and menstrual calendars.

Sample

Eligible participants (N = 286) were those who contributed ratings of sleep symptoms from the health diaries beginning in 1990 and were in the late reproductive, early or late menopausal transition stages, or early postmenopause during the course of the study. Women whose data were available for analysis and were eligible for inclusion were midlife women with a mean age of 41.4 years (SD = 4.3) at the beginning of the study, 15.9 years of education (SD = 2.8), and a median family income of $38,800 (SD = $15,000). Most (87%) of the eligible participants were currently employed, 71% married or partnered, 22% divorced or separated or widowed, and 7% never married or partnered. Eligible women described themselves as follows: 7% African American, 9% Asian American, 82% Caucasian. As seen in Table 1, women who were included in these analyses compared to those who were ineligible were similar with respect to employment status, marital status, age, and education. They differed significantly by income and ethnicity: those who were included in the analyses had higher incomes and were more likely to be Caucasian. Data obtained during any occasions of hormone use were not included in the analyses presented here except for those analyses focusing specifically on the effects of hormone therapy use (coded yes/no) as a covariate.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of the eligible and ineligible women in the mixed effects modeling analyses of sleep symptoms at start of study (1990-1991)

| Eligible Women (n = 286) | Ineligible Women (n = 222) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value* |

| Age (years) | 41.4 (4.3) | 42.1 (5.0) | 0.09 |

| Years of education | 15.9 (2.8) | 15.4 (3.1) | 0.07 |

| Family income ($) | 38,800 (15,000) | 35,600 (17,400) | 0.02 |

| Characteristic | N (Percent) | N (Percent) | P value** |

| Currently employed | 0.53 | ||

| Yes | 249 (87.1) | 189 (85.1) | |

| No | 37 (12.9) | 33 (14.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity | < 0.0001 | ||

| African American | 20 (7.0) | 38 (17.1) | |

| Asian /Pacific Islander | 26 (9.1) | 17 (7.7) | |

| Caucasian | 235 (82.2) | 156 (70.3) | |

| Other (Hispanic, Mixed) | 5 (1.7) | 11 (4.9) | |

| Marital Status | 0.31 | ||

| Married/partnered | 203 (71.0) | 145 (65.3) | |

| Divorced/widowed/not partnered | 63 (22.0) | 62 (27.9) | |

| Never married/partnered | 20 (7.0) | 15 (6.8) |

Independent t-test;

Χ2 test

Measures

The concepts and measures used in these analyses as shown in Figure 1 included sleep symptoms; age; MT-related factors (menopausal transition stage, urinary estrone glucuronide, FSH, and testosterone; hormone therapy use); stress-related factors (perceived stress, history of sexual abuse, cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine); symptoms (hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain and backache); and health-related factors (perceived health, amount of alcohol, caffeine drinks, smoking and exercise).

Urinary assays

Urinary assays were performed in our laboratories using a first-voided morning urine specimen provided on day 6 of the menstrual cycle, if menstrual periods were identifiable. For women with no bleeding or spotting or extremely erratic flow, a consistent date each month was used. Women abstained from smoking, caffeine use, and exercise before the urine collection. Urine samples were preserved with sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and sodium metabisulfite and frozen at −70°C. All specimens, standards and controls were tested in duplicate; those with a coefficient of variance > 15% were repeated. A BioRad Quantitative Urine control and a pooled in-house urine control were included in all assays, and a member of the standard curve was repeated after every 10 unknowns to monitor assay performance. In general, all samples from a calendar year were assayed during the next calendar year, and multiple samples from each participant were assayed in the same batch during each year. All endocrine concentrations were corrected for variations in urine concentration by expressing the hormone level as a ratio to the concentration in the same urine specimen.

Sleep symptoms

Sleep symptoms were assessed in the diary and included difficulty getting to sleep, awakening during the night, and early morning awakening, Women rated the severity of their symptoms on a scale where 0 indicated not present to 4, which indicated extreme.

Menopausal transition-related factors

Menopausal transition-related factors included MT stage, urinary estrone glucuronide, testosterone, FSH, and menopause-related hormone therapy use. Menopause-related hormone therapy use did not include oral contraceptives or use of progestin alone. Using menstrual calendar data, women not taking any type of estrogen or progestin were classified according to stages of reproductive aging: late reproductive, early menopausal transition, late menopausal transition, or early postmenopause, based on staging criteria developed by Mitchell, Woods, and Mariella19 and validated by the ReSTAGE collaboration.20–22 The names of stages match those recommended at the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW).13 The time before the onset of persistent menstrual irregularity during midlife was labeled the late reproductive stage when cycles were regular. Early stage was defined as persistent irregularity of more than 6 days absolute difference between any 2 consecutive menstrual cycles during the calendar year, with no skipped periods. Late transition stage was defined as persistent skipping of one or more menstrual periods. A skipped period was defined as double the modal cycle length or more for the calendar year. In the absence of a modal cycle length, a population-based cycle length of 29 days was used.23 Persistence meant the event, irregular cycle or skipped period, occurred one or more times in the subsequent 12 months. Final menstrual period (FMP) was identified retrospectively after one year of amenorrhea without any known explanation. The date of the FMP is synonymous with the term menopause. Early postmenopause was within 5 years of the FMP.

Urinary estrone glucuronide (E1G)

E1G was selected to assess estrogens because it is stable, can be reliably measured without special preparation, and is highly correlated with serum estradiol levels.24–29 Urinary E1G was measured by a competitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) that cross-reacts 83% with estradiol glucuronide and < 10% with free estrone, estrone sulfate, estriol glucuronide, estradiol, and estriol.26 The assay is described in detail elsewhere.26 The lower limit of detection for the assay was 3.1 nmol/L. Average recovery from a urine matrix of low, medium, and high E1G standard doses was 101%.26 Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were 2.1% and 9.6%, respectively, for an external (BioRad) urine control (mean concentration 2.1ng/mL); and 2.8% and 14.5%, respectively, for an internal urine control (mean concentration 1.59 ng/mL) (determined using the method of Robard from 20 randomly selected plates).

Urinary FSH

Urinary FSH was assayed using Diagnostic Products Corporation (DPC) Double Antibody FSH Kit, using a radioimmunoassay (RIA) designed for the quantitative measurement of FSH in serum and urine. The procedure is described in detail elsewhere.30 The reporting range for urine FSH was 2.0 to100 mIU/mL; the minimum detectable concentration was 1.6 mIU. The inter-assay variation was 7.1%, and the intra-assay variation was 3.7% (N = 205). FSH, as well as other assays were adjusted for urinary creatinine, which was assayed in urine specimens using the method of Jaffe.31 The inter-assay variation (run to run) was 6.7%, and the intra-assay variation was 3.1% (N = 405).

Urinary testosterone (T)

Urinary testosterone levels were assayed using the Siemens Total Testosterone Kit, a solid-phase RIA using a testosterone-specific antibody immobilized to the wall of a polypropylene tube. The assay is described in detail elsewhere.32,33 Inter-assay variation was 12.38% (N = 791), and intra-assay variation was 8.75%.

Stress-related factors

Stress-related factors included perceived stress and history of sexual abuse as well as urinary cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. Perceived stress was assessed in the diary with a question “how stressful was your day?” which women rated from 0 (not at all) to 6 (extremely, a lot). Brantley et al.34 found that a global stress rating and the sum of stress ratings across multiple dimensions correlated significantly (r = 0.35, P < 0.01). Sexual abuse history was assessed by asking “Have you ever been sexually assaulted, abused, or molested?” These data were obtained in 1999-2002 in the annual health update questionnaire. Also, beginning in 1996 and through the end of the study, we asked “during the past year did you experience any sexual abuse or sexual assault?” A cumulative variable was created to represent any history of sexual abuse or assault and coded as 1 for yes and 0 for no.

Urinary cortisol

Urinary cortisol levels were determined by radioimmunoassay using Coat-A-Count Cortisol Kit (Siemens Medical Solutions, Los Angeles, CA) and is described in detail elsewhere.33 Coat-A-Count Cortisol is designed for the quantitative measurement of unbound cortisol (hydrocortisone, Compound F) in serum, urine, and heparinized plasma. The assay is highly specific for cortisol and has extremely low cross-reactivity with other steroids, except for prednisolone. In our laboratory the reporting range for this urinary cortisol assay is 1 to 50 μg/dL; the minimum detectable concentration is 0.2 ug/dL. Inter-assay precision was calculated for each of 3 samples from the results of 20 extractions each. The coefficients of variation (inter-assay) ranged from 8.2% to 12.5% for samples ranging from 0.9 to 8.3 μg/dL. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 4.6% (N = 376) using a pooled in-house control (3.6 μg/dL). There were no significant differences in cortisol values when we compared the DCM extraction to values obtained with an additional chromatographic purification step using a disposable SepPak C-18 cartridge, after initial DCM extraction. Recovery rates ranged from 88.4% to 96.5% when samples were spiked with 3 cortisol solutions of 5, 10, and 20 μg/dL.

Urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine

These were assayed by HPLC after extraction on Bio-Rex cation exchange resin (Bio-Rad) followed by aluminum oxide (Bio-Rad) precipitation using a modification of the LCEC Application Note No. 15 (Bioanal. Syst., 1982) and described in detail elsewhere.33 An internal standard, 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine (DHBA), was mixed with all standards and unknowns prior to extraction. All data were quantitated on peak area ratios, using a standard curve generated in each batch run. The intra-assay variation was 4.7%, and the inter-assay variation was 7.85%.

Health-related factors

Health-related factors included perceived health, amount of smoking, alcohol use, and exercise. Perceived health was measured in the diary from the beginning of the study using the question “how healthy did you feel today?” Women rated their perceived health from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely, a lot). Women were asked to indicate in the daily health diary whether or not they smoked (coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes; and if yes, the number of cigarettes smoked that day), the amount of alcohol drunk, number of caffeine-containing drinks, and the amount they exercised. Exercise was determined using the question: how many total minutes of non-work related exercise did you do today? (walking, running, biking, swimming, aerobics, sports, workout, gardening, yard work).

Medication use was coded from the health diaries and included medications that fell into categories such as androgens, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), sedatives, and antipsychotics. These variables were used to exclude datapoints from the analyses where medication use would likely confound the relationship being tested. Use was coded 1 for “yes” or 0 for “no” for each time point.

Symptoms

Hot flash severity was assessed several times each year in the symptom diary, in which women rated their symptoms from 0 (not present) to 4 (extreme). Depressed mood (feeling sad or blue), anxiety, joint pain, and backache symptoms were assessed in a similar fashion.

Analyses

Mixed effects modeling using the R library35–39 was used to investigate whether age, MT stage, factors related to the menopausal transition, stress-related factors, symptoms, and health-related factors were significant predictors of each of the sleep symptoms over time. Age was centered at the group mean to enable the interpretation of the effect of age on each sleep symptoms.33

The initial series of models tested age alone as a predictor of each of the sleep symptoms. Using awakening during the night as an example, the first model postulated that overall levels of awakening during the night could differ from woman to woman (random intercept), but the scores would change with age in a common manner (fixed slope). The second model extended the first to postulate that each woman had a different mean level of awakening during the night and rate of change (random intercept, random slope). The best fitting model (fixed or random slope) was assessed by using maximum likelihood estimation with Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).39 When the best fitting model was found, that model was extended by adding covariates iteratively to test the effect on awakening during the night over time. Next, all covariates that significantly improved the model fit to the data when entered individually were added simultaneously into a final model. Finally, a reduced final model was considered using only the significant variables from the final model. Because we were using these analyses as a basis for explanation and to stimulate further mechanistic studies, a P value of 0.05 was used as the criterion for significance. Different numbers of women and observations occurred with each variable tested because the analysis required pairing of observations of the outcome and predictor variables at each time point. For example, in cases of medication use that could confound the results, data were omitted from analyses for that occasion. In addition, we excluded data points when a covariate and the outcome variable did not match in time.

RESULTS

Table 2 includes a description of the severity of the sleep symptoms across the late reproductive stage, early and late menopausal transition stages, and early postmenopause. The number and proportion of women reporting severity levels of the symptom, e.g., problem getting to sleep, ranging from 0 (no experience) to 3-4 (moderately severe to extreme) are given. The proportion of women reporting more severe sleep symptoms tends to increase as women experience the late menopausal transition stage and early postmenopause and the average severity level for awakening during the night tends to be higher than that of the other symptoms. The sleep symptoms were correlated with one another: across all stages studied problem getting to sleep was significantly correlated with both awakening during the night (r = 9.507, P < 0.0001) and early morning awakening (r = 0.449, P < 0.0001) and awakening during the night with early morning awakening (r = 0.645, P < 0.0001; n = 6542 observations of each variable).

Table 2.

Sleep symptom severity the menopausal transition stages and early postmenopause: number of observations (number of women)

| Problem getting to sleep: severity level | Late reproductive stage | Early stage | Late stage | Early postmenopause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2557 (195) | 1947 (167) | 1060 (102) | 976 (65) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| 0 | 64 (32.8) | 61 (36.5) | 34 (33.3) | 15 (23.1) |

| 0.01–0.99 | 115 (59.0) | 89 (53.3) | 51 (50.0) | 44 (67.8) |

| 1.0–1.99 | 14 (7.2) | 14 (8.4) | 16 (15.7) | 5 (7.7) |

| 2.0–2.99 | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (< 0.01) | 1 (1.5) |

| 3.0–4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Range | 0-2.92 | 0-2.87 | 0-2.33 | 0-2.50 |

| Awakening during the night: severity level | ||||

| 0 | 44 (22.6) | 35 (20.9) | 17 (16.7) | 8 (12.3) |

| 0.01–0.99 | 116 (59.5) | 96 (57.5) | 54 (52.9) | 33 (50.8) |

| 1.0–1.99 | 30 (15.4) | 26 (15.6) | 21 (20.6) | 16 (24.6) |

| 2.0–2.99 | 5 (2.6) | 9 (5.4) | 8 (7.8) | 7 (10.8) |

| 3.0–4.0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Range | 0-2.90 | 0-3.0 | 0-3.89 | 0-3.97 |

| Early morning awakening: severity level | ||||

| 0 | 61 (31.3) | 52 (30.5) | 19 (18.6) | 10 (15.4) |

| 0.01–0.99 | 112 (57.4) | 91 (54.5) | 57 (55.9) | 34 (52.3) |

| 1.0–1.99 | 20 (10.3) | 19 (11.4) | 18 (17.6) | 16 (24.6) |

| 2.0–2.99 | 2 (1.0) | 5 (3.0) | 7 (6.9) | 5 (7.7) |

| 3.0–4.0 | 0 | 1 (< 0.01) | 1 (0.01) | 0 |

| Range | 0-2.56 | 0-3.25 | 0-3.33 | 0-2.67 |

Results in Table 3 describe all 6 model parameters for problem getting to sleep. The intercept (β1) is the initial or baseline mean value for awakening during the night at age 47.4 for this population and has significant variability (P = < 0.0001). Age was centered at 47.4 years, the mean for the women whose data were used in the following analyses, to enhance interpretation of the effect of age on problem getting to sleep. When age effects on problem getting to sleep were analyzed using a random intercept, fixed slope model vs a random intercept, random slope model, the latter provided a significantly better fit to the data (AIC 13668.13 vs 1336.90, P < 0.0001). When age was considered alone using a random effects model, at age 47.4 the mean level of problem getting to sleep was 0.336 with a nonsignificant increase of 0.002 per year.

Table 3.

Random effects models for problem getting to sleep with age as predictor (β2) and with individual covariates (β3)*

| Mean Values (P values) |

Standard Deviations |

Number |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β1** | β2** | β3** | σ1*** | σ2*** | σε*** | Women | Observations |

| Age (47.4) | 0.336 | 0.002 (0.558) | - | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| Menopausal Transition Factors | ||||||||

| MT-stage | 0.348 (< 0.0001) | 0.004 (0.353) | 44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 | |

| Early | −0.007 (0.795) | |||||||

| Late | −0.036 (0.300) | |||||||

| Early PM | −0.030 (< 0.0001) | |||||||

| Estrone glucuronide (log10) (1.2) | 0.370 (< 0.0001) | −0.010 (0.097) | −0.035 (0.193) | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 130 | 4558 |

| FSH (log10) (1.1) | 0.369 (< 0.001) | −0.010 (0.100) | 0.003 (0.873) | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 130 | 4557 |

| Testosterone (log10) (1.2) | 0.369 (< 0.0001) | −0.010 (0.100) | −0.017 (0.421) | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 130 | 4559 |

| HRT use | 0.356 (< 0.0001) | 0.002 (0.491) | −0.019 (0.516) | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 379 | 8685 |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| Hot flashes | 0.319 (< 0.0001) | < -0.001 (0.964) | 0.495 (< 0.0001) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6311 |

| Depressed mood | 0.229 (< 0.0001) | 0.001 (0.878) | 0.180 (< 0.0001) | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 282 | 5784 |

| Anxiety | 0.221 (< 0.0001) | 0.002 (0.578) | 0.156 (< 0.0001) | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| Joint aches | 0.311 (< 0.0001) | 0.001 (0.795) | 0.039 (< 0.0001) | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6400 |

| Backache | 0.322 (< 0.0001) | 0.003 (0.497) | 0.027 (0.007) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6400 |

| Stress-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.208 (< 0.0001) | 0.005 (0.253) | 0.052 (< 0.0001) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| History of sexual abuse | 0.280 (< 0.0001) | 0.001 (0.830) | 0.181 (0.007) | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 231 | 6345 |

| Cortisol | −2.040 (0.026) | −0.010 (0.116) | −0.053 (0.009) | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 130 | 4362 |

| Epinephrine | −0.367 (< 0.0001) | −0.011 (0.099) | 0.009 (0.291) | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 130 | 3007 |

| Norepi-nephrine | 0.366 (< 0.0001) | 0.013 (0.057) | 0.040 (0.219) | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 130 | 3007 |

| Health-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived health | 0.724 (< 0.0001) | 0.003 (0.464) | −0.099 (< 0.0001) | 0.42 | 0.003 | −0.10 | 286 | 6542 |

| Number cigarettes smoked | 0.339 (< 0.0001) | 0.002 (0.579) | −0.001 (0.604) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of exercise | 0.343 (< 0.0001) | 0.003 (0.539) | −0.001 (0.210) | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of alcohol | 0.350 (< 0.0001) | 0.003 (0.520) | −0.023 (0.046) | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6542 |

| Caffeine-containing drinks - number | 0.297 (< 0.0001) | 0.001 (0.731) | 0.020 (0.006) | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 286 | 6380 |

Occasions on which selected medications were used were omitted from the analyses. Androgen use occasions were excluded from all analyses. Occasions when medications could affect symptoms such as sleep, hot flashes, and mood were excluded from these analyses.

β1, β2, β3 are the fixed effects (group averages) for the intercept, slope and covariate.

σ1, σ2, σε are the random effects (variability) for the intercept, slope and residual error.

The slope (β2) is the mean increase or decrease in problem getting to sleep per year, while the covariate value (β3) is the mean increase or decrease from the intercept in problem getting to sleep with each unit of change in the covariate. For example, the hot flash response range is from 0-4. With hot flash severity as a covariate with age in the equation the mean problem getting to sleep at age 47.4 for this population at the start of the study (β1) was 0.319. The problem of getting to sleep increased by < 0.001 units (β2) per year during the study, and for every 1 unit increase in hot flash severity, awakening during the night increased significantly by 0.495 units (β3).

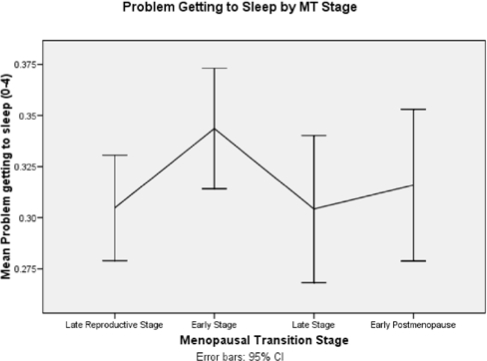

When problem getting to sleep was analyzed over time by age and with each covariate added individually, it was not associated with age, but did decrease during the early PM (β = −0.030, P < 0.0001) (See Figure 2 and Table 3). There was no association between E1G, FSH, testosterone, or hormone therapy use and problem getting to sleep. In contrast, higher severity of all symptoms (hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety joint pain, and backache) was significantly associated with greater difficulty getting to sleep (βs = 0.495, 0.180, 0.156, 0.039, 0.027 respectively; P < 0.0001 for all but backache, which was 0.007). Greater perceived stress and having a history of sexual abuse were significantly associated with difficulty getting to sleep (βs = 0.052, 0.181, respectively, P < 0.0001, 0.007), but women with higher morning cortisol levels had less difficulty getting to sleep (β = −0.053,P = 0.009). Both better perceived health and more alcohol use were associated with less difficulty getting to sleep (βs = −0.099, −0.023, P < 0.0001, 0.046 respectively) and the number of caffeine-containing drinks consumed was associated with more difficulty getting to sleep (βs = 0.020, P = 0.006). The results of the final multivariate analysis for difficulty getting to sleep included better perceived health (P < 0.0001), more severe hot flashes (P = 0.015), depressed mood (P < 0.0001), anxiety (P < 0.0001), lower cortisol levels (P = 0.026), and number of caffeine-containing drinks (β = 0.023, P = 0.023).

Figure 2.

Problem getting to sleep by menopausal transition stages

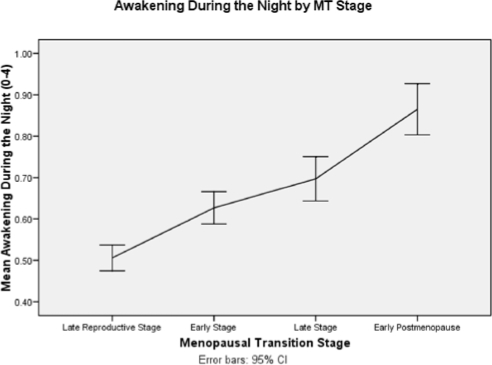

When awakening during the night was analyzed over time by age and with each covariate added individually, there was a significant increase with age as mentioned above and also during the late menopausal transition (MT) stage (β = 0.154, P < 0.0001) and early postmenopause (PM) (β = 0.272, P < 0.0001; Figure 3) Higher levels of FSH were also associated with increasing severity (β = 0.073, P < 0.0001) and greater E1G levels with decreasing severity of awakening during the night (β = 0.076, P = 0.026), but testosterone did not have a significant effect (Table 4). Hormone therapy use did not affect awakening during the night. More severe hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain, and backache were each associated with increasing severity of awakening during the night (βs = 0.198, 0.144, 0.105, 0.070, 0.049, with all P < 0.0001). Also greater levels of perceived stress (β = 0.051, P < 0.0001) and history of sexual abuse (β = 0.229, P < 0.008) were significantly associated with awakening during the night, but cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine were not. Better perceived health (β = −0.110, P < 0.0001) and more alcohol use (β = −0.032, P < 0.031) were associated with decreased severity of awakening during the night, but exercise, smoking, and number of caffeine-containing drinks did not have significant effects. All individual covariates with significant P values were added to a multivariate model to determine which subset would have the greatest effect on severity of awakening during the night. The results of the final multivariate model for awakening during the night included positive effects of age (P = 0.0027), hot flashes (P < 0.0001), and depressed mood (P < 0.0001), and negative effects of perceived health (P < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Awakening during the night by menopausal transition stages

Table 4.

Random effects models for awakening during the night with age as predictor (β2) and with individual covariates (β3)*

| Mean Values (P values) |

Standard Deviations |

Number |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β1** | β2** | β3** | σ1*** | σ2*** | σε*** | Women | Observations |

| Age (47.4) | 0.028 | 0.03 (< 0.0001) | - | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 286 | 6542 |

| Menopausal Transition Factors | ||||||||

| MT-stage | 0.585 (< 0.0001) | 0.015 (0.030) | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6542 | |

| Early | 0.027 (0.420) | |||||||

| Late | 0.154 (< 0.0005) | |||||||

| Early PM | 0.272 (< 0.0001) | |||||||

| Estrone glucuronide (log10) (1.2) | 0.691 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (0.007) | −0.076 (0.026) | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 130 | 4558 |

| FSH (log10) (1.1) | 0.689 (< 0.0001) | 0.026 (0.017) | 0.073 (< 0.0001) | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 130 | 4557 |

| Testosterone (log10) (1.2) | 0.694 (< 0.0001) | 0.030 (0.006) | −0.021 (0.415) | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 130 | 4559 |

| HRT use | 0.714 (< 0.0001) | 0.030 (< 0.0001) | −0.038 (0.317) | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 379 | 8685 |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| Hot flashes | 0.581 (< 0.0001) | 0.018 (0.003) | 0.198 (< 0.0001) | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 286 | 6311 |

| Depressed mood | 0.553 (< 0.0001) | 0.027 (< 0.000) | 0.144 (< 0.0001) | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 282 | 5784 |

| Anxiety | 0.570 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.000) | 0.105 (< 0.0001) | 0.61 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6542 |

| Joint aches | 0.599 (< 0.0001) | 0.025 (< 0.000) | 0.070 (< 0.0001) | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6400 |

| Backache | 0.618 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | 0.049 (< 0.0001) | 0.61 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6400 |

| Stress-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.522 (< 0.0001) | 0.030 (< 0.0001) | 0.051 (< 0.0001) | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6542 |

| History of sexual abuse | 0.571 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | 0.229 (0.008) | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 231 | 6345 |

| Cortisol | 0.880 (0.446) | 0.025 (0.023) | 0.004 (0.864) | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 130 | 4362 |

| Epinephrine | 0.692 (< 0.0001) | 0.031 (0.006) | 0.013 (0.231) | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 130 | 3007 |

| Norepi-nephrine | 0.690 (< 0.0001) | 0.030 (0.009) | 0.004 (0.915) | 0.67 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 130 | 3007 |

| Health-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived health | 1.08 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | −0.110 (< 0.0001) | 0.61 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6542 |

| N Cigarettes smoked | 0.660 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | −0.006 (0.062) | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of exercise | 0.651 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | −0.001 (0.596) | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of alcohol | 0.666 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | −0.032 (0.031) | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 286 | 6542 |

| Caffeine-containing drinks - number | 0.650 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | < 0.0001 (0.960) | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 286 | 6380 |

Occasions on which selected medications were used were omitted from the analyses. Androgen use occasions were excluded from all analyses. Occasions when medications could affect symptoms such as sleep, hot flashes, and mood were excluded from these analyses.

β1, β2, β3 are the fixed effects (group averages) for the intercept, slope and covariate.

σ1, σ2, σε are the random effects (variability) for the intercept, slope and residual error.

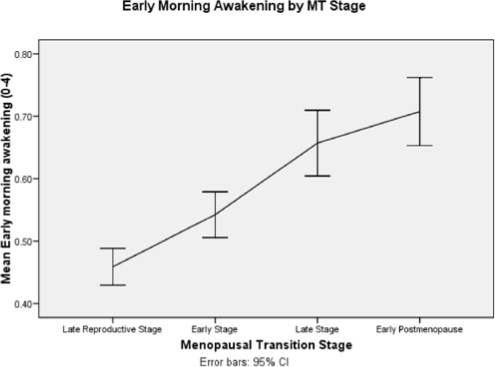

When early morning awakening was analyzed over time by age and with each covariate added individually it increased with (β = 0.029, P < 0.0001), but not with MT stages (Figure 4 and Table 5). Higher estrone levels were related to less severe early morning awakening (β = −0.079, P = 0.018), but FSH, testosterone, and hormone therapy use were not. Greater severity of each of the symptoms (hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain, and backache) was associated with more severe early morning awakening (βs = 0.105. 0.148, 0.126, 0.543, 0.043, respectively; all P < 0.0001). Greater perceived stress, a history of sexual abuse, and higher epinephrine levels were associated with more severe early morning awakening (βs = 0.062, 0.242, 0.23, respectively, P < 0.0001, 0.001, and 0.038, respectively), but cortisol and norepinephrine were not. Better perceived health was associated with less severe early morning awakening (β = −0.093, P < 0.0001) but smoking, exercise, number of caffeine-containing drinks, and use of alcohol were not. The results of the final multivariate model of early morning awakening included greater age (P < 0.0001), better perceived health (P < 0.0001), and more severe hot flashes, depressed mood, and anxiety (all P < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Early morning awakening by menopausal transition stages

Table 5.

Random effects models for early morning awakening with age as predictor (β2) and with individual covariates (β3)*

| Mean Values (P values) |

Standard Deviations |

Number |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β1** | β2** | β3** | σ1*** | σ2*** | σε*** | Women | Observations |

| Age (47.4) | 0.540 | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | - | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Menopausal Transition Factors | ||||||||

| MT-stage | 0.547 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | 56 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 | |

| Early | −0.022 (0.475) | |||||||

| Late | 0.026 (0.537) | |||||||

| Early PM | −0.022 (0.689) | |||||||

| Estrone glucuronide (log10) (1.2) | 0.660 (< 0.0001) | 0.005 (0.641) | −0.079 (0.018) | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 130 | 4558 |

| FSH (log10) (1.1) | 0.660 (< 0.0001) | 0.004 (0.692) | 0.018 (0.398) | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 130 | 4557 |

| Testosterone (log10) (1.2) | 0.657 (< 0.0001) | 0.005 (0.611) | 0.010 (0.700) | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 130 | 4459 |

| HRT use | 0.563 (< 0.0001) | 0.033 (< 0.0001) | −0.054 (0.138) | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 379 | 8685 |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| Hot flashes | 0.502 (< 0.0001) | 0.023 (< 0.0001) | 0.105 (< 0.0001) | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 286 | 6311 |

| Depressed mood | 0.444 (< 0.0001) | 0.030 (< 0.0001) | 0.148 (< 0.0001) | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 282 | 5784 |

| Anxiety | 0.447 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | 0.126 (< 0.0001) | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Joint aches | 0.537 (< 0.0001) | 0.064 (0.795) | .593 (< 0.0001) | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 286 | 6400 |

| Backache | 0.510 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | 0.043 (< 0.0001) | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 286 | 6400 |

| Stress-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.387 (< 0.0001) | 0.032 (< 0.0001) | 0.062 (< 0.0001) | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| History of sexual abuse | 0.466 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | 0.242 (0.001) | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 231 | 6345 |

| Cortisol | 0.660 (< 0.0001) | 0.001 (0.959) | 0.0003 (0.154) | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 130 | 4362 |

| Epinephrine | 0.663 (< 0.0001) | 0.007 (0.468) | 0.023 (0.038) | 9.64 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 130 | 3007 |

| Norepi-nephrine | 0.666 (< 0.0001) | 0.004 (0.690) | 0.046 (0.366) | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 130 | 3007 |

| Health-Related Factors | ||||||||

| Perceived health | 0.905 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | −0.093 (< 0.0001) | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Number cigarettes smoked | 0.551 (< 0.0001) | 0.028 (< 0.0001) | −0.006 (0.062) | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of exercise | 0.545 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | −0.001 (0.536) | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Amount of alcohol | 0.540 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | 0.002 (0.909) | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6542 |

| Caffeine-containing drinks - number | 0.529 (< 0.0001) | 0.029 (< 0.0001) | 0.007 (0.418) | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 286 | 6380 |

Occasions on which selected medications were used were omitted from the analyses. Androgen use occasions were excluded from all analyses. Occasions when medications could affect symptoms such as sleep, hot flashes, and mood were excluded from these analyses.

β1, β2, β3 are the fixed effects (group averages) for the intercept, slope and covariate.

σ1, σ2, σε are the random effects (variability) for the intercept, slope and residual error.

DISCUSSION

The three sleep problems studied as part of the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study did not change uniformly over the menopausal transition and early postmenopause, nor did they change uniformly with estrone or FSH as might have been anticipated were they each a function of the menopausal transition. Indeed, only night-time awakening seemed to worsen with progression through the late menopausal transition and early postmenopause and with HPO axis changes as indicated by lower estrone and higher FSH levels. Difficulty getting to sleep was less severe during the early PM and early morning awakening was associated only with lower estrone levels, consistent with earlier studies of the menopausal transition and sleep symptoms.8–10 Both awakening during the night and early morning awakening increased in severity as women aged, but difficulty getting to sleep was unrelated to age.

Of interest was that each of the symptoms (hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, joint pain, and backache) and perceived stress, history of sexual abuse, and perceived health were associated with each of the sleep symptoms (difficulty getting to sleep, nighttime awakening, and early morning awakening). The association of symptoms and perceived stress with each of the sleep symptoms was consistent with the findings of Shaver and associates who noted that sleep difficulty during midlife was a function of hot flashes, somatic symptoms, stress, and distress. Indeed, women who had complained of insomnia, compared to those who did not as assessed by either self-report or PSG, scored higher on the symptom distress scale of the SCL-90, the global severity scale, and on the somatization scale, and reported more hot flashes, somatic symptoms, stress, and higher neuroendocrine stress arousal.3–7 Moreover, among women without either evidence of PSG-assessed insomnia or self-reported insomnia, perceived stress was correlated negatively with amount of time awake after sleep onset and PSG-assessed sleep onset latency, indicating that women with higher perceived stress levels took more time to get to sleep, but were less wakeful after sleep onset.6 Women with self-reported insomnia also showed positive trends between stress exposure and sleep efficiency, suggesting that stress may have a differential response on sleep onset and sleep maintenance.6

Reported sexual abuse history was associated with each of the sleep symptoms reported by the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study cohort. Prior studies of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse have established a higher level of sleep difficulties40 as well as elevated levels of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine among those with PTSD41–42; but in some studies, early morning cortisol levels are similar for women abuse survivors with PTSD and non-abused women or abused women without PTSD.41 Results of most studies suggest that the HPA and autonomic nervous system may mediate the relationships between sexual abuse history and sleep symptoms.

Shaver and colleagues found that neither epinephrine nor norepinephrine was associated with sleep in their studies of midlife women.6 We found that epinephrine was associated with early morning awakening, but this symptom was not reported in Shaver's study. Shaver also found that women with PSG-identified insomnia had higher differences in am to pm cortisol, but there were no significant differences for early morning cortisol levels.6 We found that women with higher cortisol levels experienced less difficulty getting to sleep than those with lower cortisol levels. This relationship may be a reflection of women with higher morning cortisol levels having greater amplitude in the cortisol diurnal pattern and could suggest that greater cortisol amplitude is associated with less difficulty getting to sleep. Also these findings may be consistent with the relationship of lower morning cortisol levels and sleep problems in women with a history of sexual abuse.41,42 The relationship of cortisol levels to sleep problems appears to vary with the specific symptom. Backhhaus and colleagues found that in a mixed sample of women and men with insomnia cortisol levels were significantly lower than in women without insomnia.43 Moreover, higher salivary cortisol levels at awakening were associated with the subjective estimates of sleep quality measured by the PSQI. A lower level of salivary cortisol after awakening correlated with a higher frequency of nighttime awakenings, reduced sleep quality, and decreased feelings of recovery after awakening. Awakening cortisol was also negatively associated with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and with sleep-related cognitions, including rumination in bed and focusing on sleep-related thoughts. Thus the relationship of higher morning cortisol levels to less difficulty getting to sleep may be mediated by pre-sleep rumination and arousal and warrants further exploration.

Perceived health was significantly associated with each of the sleep symptoms, suggesting that there may be an important influence of how one appraises her health on sleep and perhaps a reciprocal relationship such that women who sleep well perceive themselves to be healthier. In prior studies of the menopausal transition, health status has been measured, but its effects on sleep have not been reported.8,9 Alcohol intake was associated negatively with both nighttime awakening and difficulty getting to sleep in the SMWHS cohort. Alcohol has been associated with sleep fragmentation in other populations, but midlife women may use modest amounts of alcohol to relax and manage stress, thus they may experience minimally disrupted sleep as a result.6 Caffeine intake was positively related to difficulty getting to sleep, but not to the other sleep symptoms, suggesting that its contribution may be through arousal. No effects of exercise or smoking on the sleep symptoms were observed, possibly due to the very low prevalence of smoking in the SMWHS cohort.

In the final multivariate models, each of the sleep symptoms was significantly affected by severity level of hot flashes, depressed mood, and perception of health. In addition, anxiety was associated with both difficulty getting to sleep and early morning awakening, but not awakening during the night. Although significant as individual covariates, stress factors and menopausal transition stages were not significant in the multivariate models. These findings may reflect the indirect influence of stress and MT stages on symptoms such that MT stages are associated with symptoms such as hot flashes, depressed mood, anxiety, and perceived health, and these, in turn, affect sleep symptoms.

Symptom management strategies should focus on managing these symptoms, as well as the sleep symptoms, and enhancing women's perceived health, as well as identifying factors that influence women's health perceptions as an avenue toward understanding how to promote perceived health. These findings suggest that sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition may be amenable to symptom management strategies that take into account the clusters of symptoms that women experience and promote women's general health rather than just focusing on the menopausal transition. Sleep hygiene interventions as well as health promotion efforts may prove useful adjuncts to managing sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition.44,45

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research, P50-NU02323, P30-NR04001, and R01-NR0414. We acknowledge the contributions of Don Percival, PhD, who designed the analytic strategies for this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Meyer PM. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351–58. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaver J, Giblin E, Lentz M, Lee K. Sleep patterns and stability in perimenopausal women. Sleep. 1988;11:556–56. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaver JL, Giblin E, Paulsen V. Sleep quality subtypes in midlife women. Sleep. 1991;14:18–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulsen V, Shaver JL. Stress, support, psychological states and sleep. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:1237–43. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90038-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaver JL, Johnston SK, Lentz MJ, Landis CA. Stress exposure, psychological distress, and physiological stress activation in midlife women with insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:793–802. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000024235.11538.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaver JL, Paulsen VM. Sleep, psychological distress, and somatic symptoms in perimenopausal women. Fam Pract Res J. 1993;13:373–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kravitz H, Zhao X, Bromberger J, et al. Sleep disturbance during the menopausal transition in a multi-ethnic community sample of women. Sleep. 2008;31:979–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sowers MF, Zheng H, Kravitz HM, et al. Sex steroid hormone profiles are related to sleep measures from polysomnography and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep. 2008;31:1339–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pien GW, Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Lin H, DeBlasis TL. Predictors of sleep quality in women in the menopausal transition. Sleep. 2008;31:991–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Oin H, et al. Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:230–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensrud KE, Stone KL, Blackwell TL, et al. Frequency and severity of hot flashes and sleep disturbance in postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Menopause. 2008;16:1–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76:874–78. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Percival DB, Smith-DiJulio K. Is the menopausal transition stressful? observations of perceived stress from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Menopause. 2009;16:90–7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817ed261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Utian WH, Boggs PP. The North American Menopause Society 1998 Menopause Survey. Part 1: Postmenopausal women's perceptions about menopause and midlife. Menopause. 1998;6:122–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Sleep disturbance in menopause. Menopause. 2007;14:826–9. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3180321a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods NF, Smith-DiJulio K, Percival DB, Tao EY, Taylor HJ, Mitchell ES. Symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause and their relation to endocrine levels over time: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. J Women's Health. 2007;16:667–77. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell ES, Woods NF, Mariella A. Three stages of the menopausal transition from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study: toward a more precise definition. Menopause. 2000;7:334–49. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow SD, Cain K, Crawford S, et al. Evaluation of four proposed bleeding criteria for the onset of late menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3432–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlow SD, Mitchell ES, Crawford S, Nan B, Little R, Taffe J. ReSTAGE Collaboration. The ReSTAGE Collaboration: defining optimal bleeding criteria for onset of early menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harlow SD, Crawford S, Dennerstein L, Burger HG, Mitchell ES, Sowers MF ReSTAGE Collaboration. Recommendations from a multi-study evaluation of proposed criteria for staging reproductive aging. Climacteric. 2007;10:112–9. doi: 10.1080/13697130701258838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiazze L, Jr, Brayer FT, Macisco JJ, Jr, Parker MP, Duffy BJ. The length and variability of the human menstrual cycle. JAMA. 1968;203:377–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denari JH, Farinati Z, Casas PR, Oliva A. Determination of ovarian function using first morning urine steroid assays. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanczyk FZ, Miyakawa I, Goebelsmann U. Direct radioimmunoassay of urinary estrogen and pregnanediol glucuronides during the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:443–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor KA, Brindle E, Holman DJ, et al. Urinary estrone conjugate and pregnanediol 3-glucuronide enzyme immunoassays for population research. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1139–48. doi: 10.1373/49.7.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker TE, Jennison KIM, Kellie AE. The direct radioimmunoassay of oestrogen glucuronides in human female urine. Biochem J. 1979;177:729–38. doi: 10.1042/bj1770729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrell RJ, O'Connor KA, Holman DJ. Monitoring the transition to menopause in a five year prospective study: aggregate and individual changes in steroid hormones and menstrual cycle lengths with age. Menopause. 2005;12:567–77. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000172265.40196.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor KA, Brindle E, Shofer JB, et al. Statistical correction for non-parallelism in a urinary enzyme immunoassay. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2004;25:259–78. doi: 10.1081/ias-200028078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qui Q, Overstreet JW, Todd H, Nakajima ST, Steward DR, Lasley BL. Total urinary follicle stimulating hormone as a biomarker for detection of early pregnancy and periimplantation spontaneous abortion. Environ Health Perspec. 1997;105:862–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taussky HH. A microcolorimetric determination of creatinine in urine by the Jaffe reaction. J Biol Chem. 1954;208:853–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dufau ML, Winters CA, Hattori M, et al. Hormonal regulation of androgen production by the Leydig cell. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20:161–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woods NF, Smith-DiJulio K, Percival DB, Mitchell ES. Cortisol levels across the menopausal transition: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Menopause. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318198d6b2. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brantley PJ, Waggoner CD, Jones GN, Rappaport NB. A Daily Stress Inventory: development, reliability, and validity. J Behav Med. 1987;10:61–74.3. doi: 10.1007/BF00845128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models, R package version 3.1. 2005:1–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2005. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar D. Lattice: Lattice Graphics. R package version 0.12-11 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. NY: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hox J. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Johnston L, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, psychiatric distress, and quality of life impairment in sexual assault survivors. J Nerv Mental Disord. 2002;190:442–52. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heim C, Newport DJ, Helt S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;285:592–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemieux AM, Coe CL. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for chronic neuroendocrine activation in women. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:105–15. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Hohagen F. Sleep disturbances are correlated with decreased orning awakening salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1184–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheek RE, Shaver JL, Lentz MJ. Lifestyle practices and nocturnal sleep in midlife women with and without insomnia. Biol Res Nurs. 2004;6:46–58. doi: 10.1177/1099800404263763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheek RE, Shaver JL, Lentz MJ. Variations in sleep hygiene practices of women with and without insomnia. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:225–36. doi: 10.1002/nur.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]