Abstract

The lens capsule compartmentalizes the cells of the avascular lens from other ocular tissues. Small molecules required for lens cell metabolism, such as glucose, salts, and waste products, freely pass through the capsule. However, the lens capsule is selectively permeable to proteins such as growth hormones and substrate carriers which are required for proper lens growth and development. We used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to characterize the diffusional behavior of various sized dextrans (3, 10, 40, 150, and 250kDa) and proteins endogenous to the lens environment (EGF, γD-crystallin, BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG) within the capsules of whole living lenses. We found that proteins had dramatically different diffusion and partition coefficients as well as capsule matrix binding affinities than similar sized dextrans, but they had comparable permeabilities. We also found ionic interactions between proteins and the capsule matrix significantly influence permeability and binding affinity, while hydrophobic interactions had less of an effect. The removal of a single anionic residue from the surface of a protein, γD-crystallin [E107A], significantly altered its permeability and matrix binding affinity in the capsule. Our data indicated that permeabilities and binding affinities in the lens capsule varied between individual proteins and cannot be predicted by isoelectric points or molecular size alone.

Keywords: lens capsule, basement membrane, diffusion coefficient, permeability, binding affinity, partition coefficient, FRAP

1. Introduction

The lens capsule is a relatively thick basement membrane completely encasing the cells of the lens, thus sequestering them from the surrounding aqueous and vitreous humors (1–4). It is multifunctional, protecting the lens epithelial and cortical fiber cells from infectious agents, providing mechanical and structural integrity during lens accommodation, as well as cell signaling during the development and growth of the lens (5,6). The main structural components of the lens capsule, collagen IV, laminin, nidogen/entactin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (7–9), self-assemble into a complex three-dimensional viscoelastic meshwork (10–13). While the composition and assembly of the capsule is similar to other basement membranes, including the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), it does differ in the identity and ratio of the isoforms present (14,15).

The basement membrane functions as a molecular sieve modulating the transport of solutes including nutrients, metabolites, and signaling molecules such as cytokines and growth factors. In the kidney, the GBM works together with slit diaphragms and capillary endothelial cells forming the glomerular barrier, restricting the passage of large proteins but allowing water and smaller proteins to pass into the urine (16,17). For the avascular lens, the lens capsule serves as the sole filter for the transit of water, nutrients, waste products, substrate carriers, and cell signaling molecules between the ocular environment and the lens cells (18–22). Both the GBM and lens capsule have a net negative charge primarily due to an abundance of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains (23–28); but the lens capsule contains several times more GAG side chains (per unit dry tissue weight) than the GBM (15,29). In addition to steric exclusion factors, these negatively charged side chains have been proposed to be responsible for the reduced permeability of proteins through the lens capsule (30). However, the effect of charge on selective permeability is still controversial in the GBM (16,30–33), and it is difficult to assess the GBM’s true contributions to glomerular permeability because of the presence of other sieving structures in the glomerular barrier (16,17,34).

While all molecules important for lens physiology must transit the capsule, the permeability parameters of the capsule have not been extensively studied. Unlike the GBM, the thickness and accessibility of the lens capsule make it an ideal basement membrane to study the mechanisms controlling selective permeability. However, early lens capsule permeability studies were typically performed using simple two-chambered systems which required whole lenses or lens capsules from large animals and were vulnerable to artifact due to the extensive tissue manipulation required to place the lens or capsule between the chambers (18–20,35–40). These experiments only measured the diffusivity of water, small charged tracer molecules, or polysaccharides, not biologically significant proteins. Other studies measured the uptake of tracking molecules or proteins into whole lenses and attempted to draw qualitative conclusions about lens permeability (41–43); but this technique makes it very difficult to distinguish between the permeability of the capsule and that of the cellular membranes.

In this study, we report a novel approach towards describing lens capsule permeability using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). This approach allows the quantitative determination of the lens capsule’s permeability to biologically significant proteins and the matrix binding affinities of these proteins to the capsules of living lenses. Because of its relative thickness and good accessibility, the lens capsule, unlike the GBM, serves as an ideal model system for studying the transport mechanisms underlying selective permeability of basement membranes. Our results on mouse lens capsules show an interesting dichotomy between the permeability and binding of proteins endogenous to the lens environment versus dextrans within lens capsule matrices. We also performed a series of protein diffusion experiments involving lens capsules with modified anionic and cationic sites as well as blocked hydrophobic interactions. Our results revealed a complex mechanism responsible for the selective permeability of the lens capsule, a mechanism based on a molecule’s size and shape as well as ionic and hydrophobic interactions.

2. Results

2.1. Permeability of the Lens Capsule

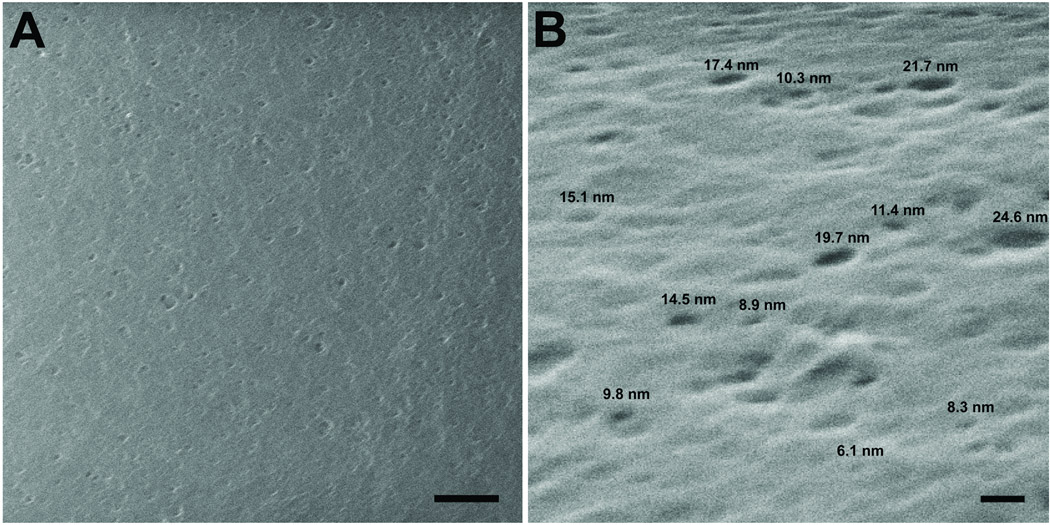

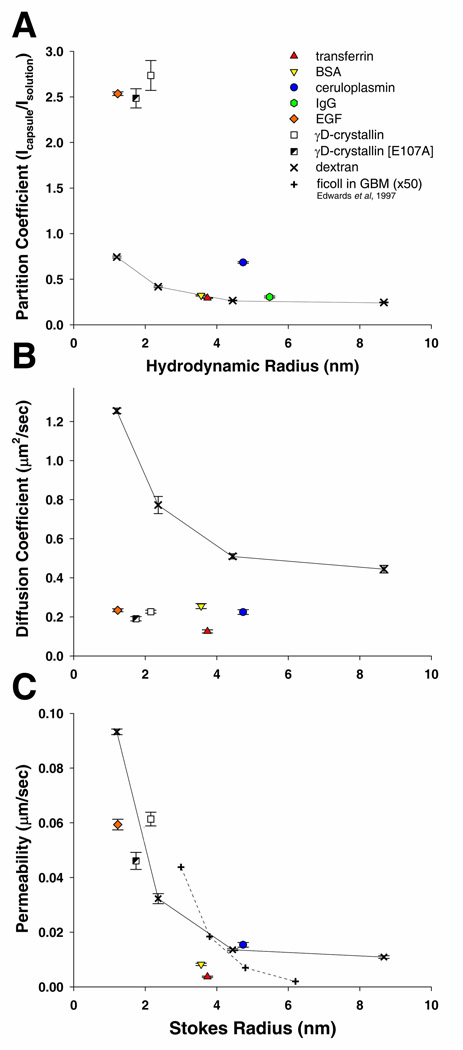

All molecules entering the avascular lens must transit the lens capsule prior to reaching the lens cells. The capsule is composed of a matrix of basement membrane molecules which create a series of intertwining pores through its entire thickness. Permeability through the capsule has been proposed to be influenced by its effective pore size and charged domains (30). The surface of the lens capsule visualized by scanning helium-ion microscopy shows the surface of the capsule interspersed with openings ranging in size from approximately 25nm to 6nm (Figure 1A, B). In order to determine how efficiently molecules of different Stokes radii (RS) would enter the capsule, the partition coefficients (Φ) of five polydisperse fluorescein labeled dextrans (highly branched and flexible polysaccharides), with nominal molecular weights of 3kDa, 10kDa, 40kDa, 150kDa and 250kDa, and seven fluorescein labeled proteins which are endogenous to the lens environment, EGF, γD-crystallin, a naturally occurring, cataract-associated mutant form of γD-crystallin [E107A] (44), BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG were determined using confocal microscopy. The physical properties of all tracers used in the study are listed in supplemental table 1 The partition coefficients measured for the 3–150kDa dextrans decreased inversely to their Stokes radii (RS), 0.74, 0.42, 0.27, and 0.25 (Figure 2A). The partition coefficient for the 250kDa dextran was 0.32, which was slightly higher than the value for the 150kDa dextran; possibly a result of the capsule matrix excluding the larger molecules of its polydispersed range (average RS of 10.9nm). Partition coefficients for the smaller proteins, EGF, WT and mutant γD-crystallin were 2.54, 2.74, and 2.49, respectively, more than 3.5 times higher than the 3kDa and 10kDa dextrans (Figure 2A). Interestingly, a single amino acid substitution of a negative glutamic acid with a neutral alanine [E107A] resulted in a 9.1% decrease in Φ for γD-crystallin. The four larger proteins, transferrin, BSA, ceruloplasmin, and IgG, each had Φ values closer to those measured for the 40kDa dextran, 0.32, 0.29, 0.68, and 0.31, respectively (Figure 2A). Experiments were also performed using fluorescein labeled IGF and insulin, however Φ could not be determined due to intramolecular fluorescence quenching (45) within the lens capsule. Values and standard errors experimentally determined in unmodified capsules can be found in supplemental table 1.

Figure 1.

Helium ion microscopy of the anterior lens capsule of an adult mouse lens A) Top down view of the anterior capsule, bar=200nm. B) Surface image acquired at a 40 degree tilt. Representative diameters are provided above selected pores, bar=20nm.

Figure 2.

Behavior of fluorescein labeled dextrans and protein in the anterior mouse lens capsule as a function of Stoke’s radius. A) The equilibrium partition coefficient of these molecules calculated by dividing the fluorescence intensity within the capsule (Icapsule) by the fluorescent intensity in solution (Isolution). B) The diffusion coefficients for the studied molecules within the capsule evaluated from FRAP recovery curves. C) The calculated permeability of dextrans and proteins in the lens capsule. These values are compared to permeability values determined for Ficoll in the glomerular basement membrane (adjusted for thickness) determined by Edwards et al, 1997.

Molecules diffusing within the lens capsule are hindered compared with free diffusion in aqueous solution, due to various physical and chemical interactions with the surrounding extracellular matrix. We describe this hindered diffusion with three parameters, the effective diffusion coefficient (D) in the lens capsule, the relative diffusivity (Dlens capsule/Dsolution), and the binding affinity ratio of the molecules to the capsule matrix (kdissociation/kassociation).

The dextrans diffused at rates inverse to their RS, 1.26, 0.77, 0.51, and 0.45µm2/s (Figure 2B) which was comparable to, but slightly slower, than the diffusion rates previously measured in the lens capsule for similarly sized dextrans using a two chambered system (38). Relative diffusivity is a useful comparison of the diffusion of a molecule in the capsule versus in solution. Interestingly, the relative diffusivity (Dcapsule/Dsolution) of the dextrans increased with their size, 0.74%, 0.89%, and 1.10%, and 1.87%. Overall, protein diffusion in the capsule was appreciably slower than for dextrans of similar sizes. Diffusion coefficients in the capsule for EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, were 0.23, 0.17, 0.18, 0.26, 0.13, and 0.22µm2/s, respectively (Figure 2B). In contrast, IgG did not diffuse sufficiently within the capsule during the time frame of the experiment (50 seconds) to provide adequate recovery curves. The relative diffusivity of proteins in the capsule was also lower than the values for dextrans, 0.14%, 0.23%, 0.15%, 0.44%, 0.23%, and 0.52%, for EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, respectively.

The permeability (P) of the lens capsule to dextrans decreased inversely to their average RS and molecular weight, 0.09, 0.03, 0.01, and 0.01µm/s, for the 3kDa, 10kDa, 40kDa, and 150kDa respectively. These values are comparable to the published permeability of the GBM (adjusted for thickness) to similar sized dextrans (46) (Figure 2C). Although the proteins were able to enter the capsule at higher equilibrium concentrations than dextrans (i.e., higher Φ), they diffused at slower rates (i.e., lower D). Therefore, some protein permeability values were in line with the values calculated for dextrans of similar RS. The lens capsule permeability values for γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], and ceruloplasmin were, 0.061, 0.046, and 0.015 µm/s, respectively, which was similar to that of comparably sized dextrans. EGF, BSA, and transferrin had markedly lower permeability values than those of similarly sized dextrans, 0.059, 0.008, and 0.004µm/s, respectively (Figure 2C).

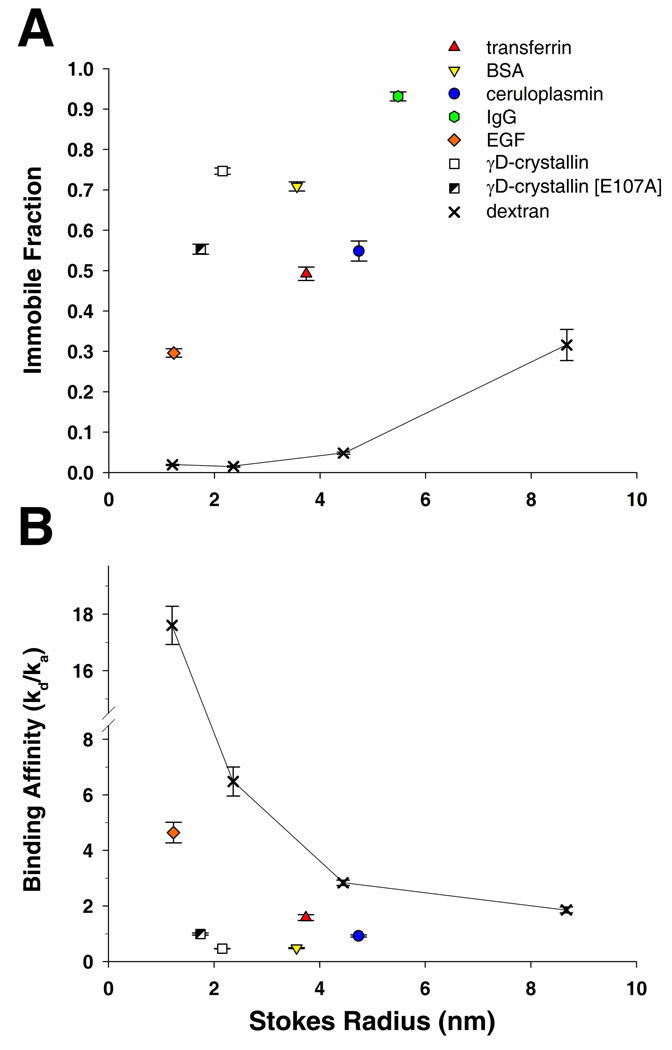

2.2. Molecule Binding in the Lens Capsule

Some proteins, especially growth factors, are known to bind to core basement membrane proteins and heparan sulfate side chains (47–50). Proteins participating in low affinity binding can be described using the ratio of the kinetic dissociation and association constants (kd/ka) which we will term as the binding affinity ratio. We also report the immobile fraction of the studied tracers from FRAP recovery curves. The immobile fraction is the unrecovered fluorescence intensity within the lens capsule after bleaching a circular region of interest (ROI) and represents bleached and unbleached fluorescein labeled molecules unable to exchange in the XY plane during the time frame of the experiment (51).

Binding strength of the tested molecules to the lens ECM varied greatly. It would be expected that a neutral polysaccharide, such as a dextran molecule, would have little binding affinity towards the capsule. This was observed for the smaller dextrans, 3kDa, 10kDa, and 40kDa, each having immobile fractions of less than 5% at the completion of the experiment (17s duration). However, close to 30% of the larger 150kDa dextran was unable to diffuse out of the ROI (Figure 3A). Proteins bound to the capsule matrix much more tightly than dextrans, with immobile fractions 5 to 50 times greater than dextrans of similar RS (50s duration). EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG had immobile fractions of 29.6%, 74.2%, 55.0%, 70.9%, 49.2%, 54.9%, and 93.2%, respectively (Figure 3A). Protein binding affinity ratios, where lower values indicate stronger binding, were at least a five times lower compared to dextrans of similar RS. Binding affinity ratios for the 3kDa, 10kDa, 40kDa, and 150kDa dextrans were 17.6, 6.5, 2.8, and 1.9, respectively. Whereas binding affinity ratios for EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin were 4.65, 0.45, 0.92, 0.49, 1.59, and 0.92, respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Lens capsule matrix interactions of fluorescein labeled dextrans and proteins. A) Comparison of the immobile fractions of each molecule and B) their binding affinity ratios evaluated from FRAP recovery curves.

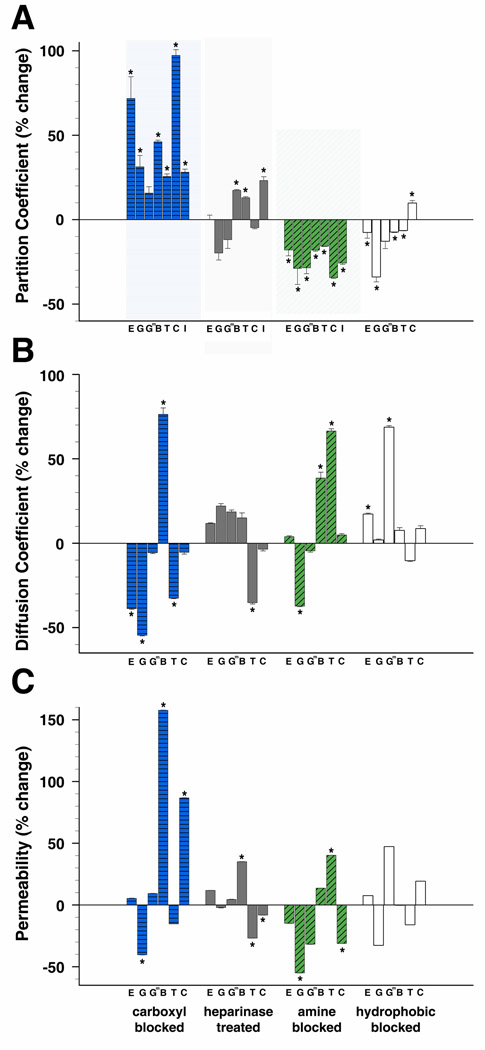

2.3. Anionic Interactions between Proteins and the Lens Capsule

We have demonstrated that proteins diffuse and interact within the lens capsule appreciably different than polysaccharides. Next we attempted to investigate how ionic and hydrophobic interactions influence protein behavior in the capsule. It is believed that size and ionic interactions between proteins and basement membranes molecules are the main determinant of protein permeability in the GBM (28,52–54); but this has only been explored in the lens capsule using relatively small charged tracer molecules (30). We investigated the influence of ionic interactions on lens capsule permeability and binding by targeting two sources of anionic charges within the lens capsule, carboxyl groups and heparan sulfate side chains, as well as a source of cationic charge, amine groups (described in the next section). Partition coefficients (Φ) increased for all proteins tested in lens capsules following the irreversible capping of carboxyl groups with glycine methyl ester. The Φ of EGF, γD-crystallin, BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG, significantly increased by 71.8%, 31.3%, 46.1%, 25.6%, 97.3%, and 28.1%, respectively, whereas the change for γD-crystallin [E107A] was not statistically significant compared to measurements in unmodified capsules (Figure 4A). In heparanase treated lens capsules, there were also significant increases in Φ for transferrin, BSA, and IgG, 23.2%, 17.4%, 13.0%, respectively; however, Φ for ceruloplasmin and EGF did not significantly change with heparanase treatment (Figure 4A). Partition coefficient percent changes, standard errors, and p values for proteins in modified capsules can be found in supplemental table 2.

Figure 4.

Change in protein behavior in mouse anterior capsules modified by neutralizing carboxyl or amine groups, removal of heparan sulfate side chains, or blocking hydrophobic interactions. Proteins are listed from smallest to largest. A) Percent change of partition coefficients from values determined in unmodified capsules. B) Percent change of diffusion coefficients from values determined in unmodified capsules. C) Percent change of permeability values from values determined in unmodified capsules. (E=EGF, G=γD-crystallin, Gm=γD-crystallin [E107A], B=BSA, T=transferrin, C=ceruloplasmin, I=IgG) (*p<=0.05)

The diffusion coefficient did not change universally as was observed for Φ in lens capsules with neutralized anionic sites. When carboxyl groups were blocked, BSA diffused significantly faster, 76.3%, whereas, transferrin, EGF, and γD-crystallin diffused significantly slower, −32.5%, −38.7%, −54.5%, respectively. Ceruloplasmin and γD-crystallin [E107A] did not significantly change when compared to values in unmodified capsules (Figure 4B). In heparanase treated capsules, only transferrin significantly slowed by −35.2%, while D did not significantly change for BSA, ceruloplasmin, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], or EGF (Figure 4B).

Changes in permeability values calculated for proteins in lens capsules with modified anionic sites varied. In capsules with blocked carboxyl groups, the permeability of BSA and ceruloplasmin both significantly increased, 157.7% and 86.7%, while γD-crystallin significantly decreased by −40.3%; EGF, γD-crystallin [E107A], and transferrin did not significantly change (Figure 4C). Permeability significantly changed for BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, 35.1%, −26.8%, and −8.1%, respectively, in lens capsules with cleaved heparan sulfate side chains, but did not change significantly for EGF, γD-crystallin, or γD-crystallin [E107A] (Figure 4C).

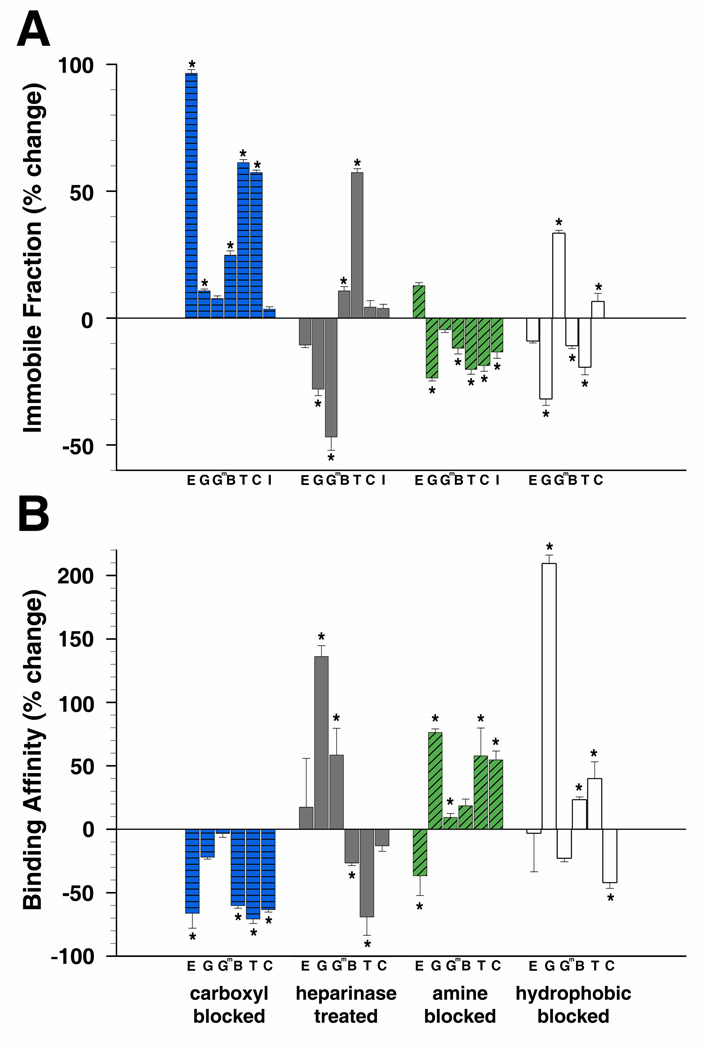

Neutralizing or removing anionic sites within the lens capsule also strengthened protein-matrix interactions. Significant increases in matrix binding were observed in these capsules for many of the proteins tested, demonstrated by significant increases in immobile fractions and decreases in binding affinity ratios. The immobile fractions of EGF, γD-crystallin, BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin increased in capsules with neutralized carboxyl groups by 96.5%, 10.7%, 24.8%, 61.3%, and 57.3%, respectively (Figure 5A) while the immobile fractions of γD-crystallin [E107A] and IgG did not significantly change. Additionally, in these capsules, the binding affinity ratios for EGF, BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin significantly decreased, −66.2%, −60.2%, −70.7%, and −63.3%, respectively, whereas γD-crystallin and γD-crystallin [E107A] did not significantly change (Figure 5B). In heparanase treated capsules, the immobile fractions of BSA and transferrin increased, 10.7% and 57.3%, while γD-crystallin and γD-crystallin [E107A] significantly decreased, −28.0% and −46.8% (Figure 5A). EGF, ceruloplasmin, and IgG did not significantly change. Similarly, significant decreases in binding affinity ratios in these capsules were observed for BSA and transferrin, −26.6% and −69.1%, and showed a decrease in binding of γD-crystallin and γD-crystallin [E107A] to the capsule, where the binding affinity ratio increased 136.1% and 58.4% (Figure 5B). No significant changes were measured for EGF and ceruloplasmin.

Figure 5.

Change in matrix interactions in modified lens capsules. A) Percent change of immobile fractions of proteins from values determined in unmodified capsules. B) Change in binding affinity ratios. (E=EGF, G=γD-crystallin, Gm=γD-crystallin [E107A], B=BSA, T=transferrin, C=ceruloplasmin, I=IgG) (*p<=0.05)

2.4. Cationic Interactions between Proteins and the Lens Capsule

Partition coefficients, diffusivity, permeability, and matrix binding were also tested in lens capsules in which cationic amine groups were irreversibly capped and neutralized with sulfo-NHS acetate. In contrast to removing anionic sites, neutralizing cationic sites in the capsule decreased Φ values of all proteins tested. EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG significantly decreased compared to values in untreated capsules, −118.0%, −28.8%, −28.5%, −18.0%, −15.7%, −34.4%, and −25.7%, respectively (Figure 4A). In these capsules, the diffusion coefficients of BSA and transferrin significantly increased, 38.6% and 66.4%; whereas, the diffusion speed of γD-crystallin significantly decreased, −37.2%, while γD-crystallin [E107A], EGF and ceruloplasmin did not significantly change (Figure 4B). Although the effects of a more negatively charged capsule on the Φ of the proteins were consistent, permeability varied. Permeability for γD-crystallin and ceruloplasmin significantly decreased by −55.0% and −31.2%, while transferrin significantly increased by 40.3% (Figure 4C). EGF, γD-crystallin [E107A], and BSA did not significantly change.

Changes in immobile fraction and binding affinity ratios in capsules with neutralized amine groups demonstrated a decrease in matrix binding for most of the proteins. The immobile fractions of γD-crystallin, BSA, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and IgG decreased by −23.6%, −11.8%, −20.2%, −18.7%, and −13.4%, respectively. EGF and γD-crystallin [E107A] did not significantly change (Figure 5A). Binding affinity ratios significantly increased for γD-crystallin, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, 76.3%, 57.9%, and 54.7%, respectively (Figure 5B). Conversely, binding affinity ratios significantly decreased by −36.7% for EGF, describing stronger matrix binding in more anionic capsules. No significant change in the binding affinity ratios of γD-crystallin [E107A] and BSA were observed.

2.5. Hydrophobic Interactions within the Lens Capsule

Soluble proteins fold into tertiary structures which hide their hydrophobic regions. However, some hydrophobic regions still remain exposed on their surfaces. We investigated the influence of hydrophobic interactions on lens capsule permeability and matrix binding by performing FRAP experiments in the presence of the mild non-ionic surfactant octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside. Partition coefficients significantly decreased for EGF, γD-crystallin, γD-crystallin [E107A], BSA, and transferrin, −7.5%, −33.8%, 12.7%, −7.2%, and −6.4%, respectively, and significantly increased by 9.8% for ceruloplasmin (Figure 4A). The rate of diffusion significantly increased by 17.2% for EGF and 68.6% for γD-crystallin [E107A], but did not significantly change for γD-crystallin, BSA, transferrin, or ceruloplasmin (Figure 4B). Overall though, permeability did not significantly change for any of the proteins tested in capsules with blocked hydrophobic interactions (Figure 4C).

For most of the proteins, blocking hydrophobic interactions with the capsule matrix altered binding. Matrix binding for BSA and transferrin decreased, as their immobile fractions decreased by −10.8% and −19.3%, and their binding affinity ratios increased by 23.2% and 39.8%, both respectively. Conversely, matrix binding increased for ceruloplasmin, with a significant increase in the immobile fraction, 6.5%, and a significant decrease in the binding affinity ratio, −41.9% (Figures 5A, B). Interestingly, substituting a single hydrophilic glutamic acid on the surface of γD-crystallin with the more hydrophobic alanine resulted in opposing changes to matrix binding in this environment (Figures 5A, B). Binding of γD-crystallin to the capsule matrix decreased when hydrophobic interactions were blocked, with a significant decrease, −31.8%, in immobile fraction and a significant increase, 209.3%, in its matrix binding affinity ratio, whereas binding increased for mutant γD-crystallin [E107A], with a 33.4% increase in the immobile fraction. Capsule matrix binding did not significantly change for EGF.

3. Discussion

In the present investigation we performed a series of experiments utilizing an in situ approach based on FRAP to fully characterize the diffusive behavior of not only polysaccharides but also proteins endogenous to the lens capsule environment and important for lens and eye health. For instance, crystallins leaking from lens fiber cells through intact capsules can cause severe eye inflammation (55). EGF, IGF, and insulin are vital for proper lens cell growth and differentiation (56), while the carrier proteins BSA, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin are responsible for the endo- and transcytotic delivery of the iron, copper, and fatty acids essential for normal cell metabolism to the lens (57–59). The FRAP method is relatively quick and non-invasive compared to the previous transport chamber method that required extensive tissue manipulation and limited their descriptions to only the sieving or diffusion coefficients of polysaccharides or water (18–20,35–40). Furthermore, we modified ionic and hydrophobic sites in the capsule matrix in order to examine their influence on solute diffusion, which has been long speculated, but was lacking in experimental evidence.

The overall permeability of these molecules through the lens capsule appeared to be inversely related to the solute size (Figure 2C); suggesting that steric exclusion between solutes and matrix pores had a strong influence on permeability. Helium ion microscopy of a native mouse lens showed openings on the surface of the capsule with a maximum diameter near 25nm. However, its effective pore size may be smaller due to the overlay of pores at different layers throughout the thickness (10 µm) of the capsule (4). In fact the effective pore size may be closer to the maximum pore diameter of 20nm which some have predicted for the GBM (60,61). Notably, experimental evidence of our predicted maximum capsule pore size is in our observation that the polydisperse 250kDa dextrans (with an average RS of 10.9nm and we estimate to have a range of 10.5–12.0nm) had limited access to the capsule matrix. This limited access we presume is a result of only the smaller molecules of the population being capable of entering the matrix pores. In other studies, larger objects (2,000kDa dextrans, RS = ~27nm; and type-5 adenovirus vectors, RS = ~49nm) were shown to pass through the lens capsule in a two chamber diffusion system (62) or after anterior chamber injection (63,64). Considering the maximum pore size we have measured in the capsule, this contradiction may suggest that the capsules used in the previous reports were compromised.

The relative diffusivity of both larger dextrans and proteins within the capsule was somewhat higher than for smaller molecules. This suggested that the lens capsule had heterogeneous pores similar to beads in a size exclusion column. In both, smaller molecules were slowed by entering smaller pores, while larger molecules were excluded and diffuse more rapidly (65).

In addition to the steric influence the capsule matrix has on solute diffusion, our data also suggested that ionic and hydrophobic interactions had a significant influence on lens capsule permeability and matrix binding. The current dogma presumes that the repulsive interactions between anionic sites on protein surfaces and the membrane matrix is the major force controlling basement membrane permeability. While it was not possible to quantitate how completely our treatments removed all charged groups from the capsule due to the presence of attached lens cells, our data show reducing the number of anionic sites in the capsule resulted in an almost universal increase in matrix binding and protein equilibrium concentrations. Conversely, cationic sites in the capsule appeared to attract proteins since reducing their number decreased matrix binding and equilibrium concentrations of most proteins. While it is possible that neutralization of carboxyl and amine groups or the removal of heparan sulfate side chains affect the structure and size of the capsule matrix pores, the lack of correlation between the equilibrium concentration and diffusion rates of proteins within modified capsules with the protein’s size makes this interpretation unlikely. It could then be presumed that the removal of an anionic patch from the surface of a protein would result in an increase in matrix binding. For the mutant γD-crystallin, the substitution of a glutamic acid for an alanine [E107A] removes an anionic patch on the protein’s surface, increasing its measured isoelectric point from 7.3 to 8.3 without altering its structure (66). However, γD-crystallin [E107A] had a significantly lower immobile fraction (p=0.004) and a significantly higher binding affinity ratio (p<0.001) in the capsule matrix compared to γD-crystallin. This indicates that the attractive forces between anionic sites on protein surfaces and the cationic sites in a membrane matrix may have more of an influence on protein behavior within basement membranes than was previously expected. In this context, the increase in binding and partition coefficients for proteins in lens capsules with neutralized carboxyl groups can conceivably be explained as an increase in cationic sites in the membrane matrix as a result of broken salt bridges.

Undoubtedly ionic interactions between proteins and the lens capsule matrix influence the behavior of proteins diffusing within a basement membrane. However, protein behavior in the capsule cannot be easily predicted based on estimated isoelectric points (67). Diffusion rates in unmodified capsules and rate changes in charge modified capsules do not correlate to a protein’s isoelectric point. Additionally, in many experiments performed in modified capsules the behavior of γD-crystallin [E107A] did not significantly change where γD-crystallin did. This suggested that a single anionic patch on the surface of a protein has a substantial influence on its ability to enter and diffuse within the lens capsule.

Our results demonstrated that molecules with charged surface regions behave very differently than uncharged polysaccharides in the capsule. Although we saw substantial differences in equilibrium concentrations and diffusion rates between dextrans and proteins, their permeability values were similar since slower protein diffusion negates the increased protein equilibrium concentrations. Despite this, capsule permeability still seemed to be influenced by charged sites within the capsule matrix.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Molecule labeling and purification

The 3kDa, 10kDa, and 40kDa dextrans (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 150kDa and 250kDa dextrans (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), BSA (#A23015, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), EGF (#E3478, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), holo-transferrin (#T2871, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and rabbit anti-goat IgG (#A10529, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were purchased as fluorescein conjugates. Ceruloplasmin (#C2026, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), IGF (#4119-1000, BioVision, Mountain View, CA), recombinant wild type γD-crystallin and mutant γD-crystallin [E107A] (66,68) were labeled using the following protocol. Proteins (10–20 mg/ml) were dialyzed into 0.1M sodium bicarbonate buffer. Fluorescein succinimidyl ester (#C1311, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (10mg/ml) was dissolved in DMSO and 100µl was added to the sodium bicarbonate buffer containing the protein then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Unreacted fluorescein was then removed using an 18ml G25 sephadex™ column. The concentration of fluorescein labeled molecules used in the experiments was approximately 1.0mg/ml, except for EGF which was used at 0.1mg/ml. This is compared to the total protein concentration of 0.3 to 0.7mg/ml reported in human and rabbit aqueous humors (69–71).

4.2. Mouse Lens Preparations

Lenses for were isolated from 8–12 week old FVB/N mice and gently rolled on paper toweling to remove extralenticular tissue. The lenses were then washed with PBS (pH 7.4) on an orbital rocker for 30–45 minutes at 90 revolutions per minute (rpm).

Carboxyl groups were capped and neutralized with glycine methyl ester (GME, #G6600, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) using the cross-linking activator 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, #26777, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Whole lenses were placed in PBS containing 0.01M GME and 0.1M EDC then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, then washed in PBS for 30–45 minutes (72).

Amine groups were capped and neutralized with sulfo-NHS acetate (#26777, Pierce, Rockford, IL). Whole lenses were placed in PBS containing sulfo-NHS acetate (6.25mg/ml) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, then washed in PBS on an orbital rocker for 30–45 minutes at 90 rpm.

Heparan sulfate side chains were enzymatically cleaved using heparanase II (#H6512, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) which cleaves heparan sulfate at both glucuronic and iduronic acid residues (73). Whole lenses were placed in 500µl of PBS containing 40 mIU heparanase II and incubated at 30°C for 4 hours. Lenses were then washed in PBS on an orbital rocker for 30–45 minutes at 90 rpm (72).

Hydrophobic interactions were blocked using the mild non-ionic surfactant octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (#O8001, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Whole lenses were placed in a PBS solution containing 10mM of octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (less than half its critical micelle concentration) (74) for 30 minutes at room temperature prior to each experiment. Loading and FRAP experiments were then carried out in fresh surfactant solution containing the labeled proteins.

Although the precise efficiency of each treatment was not accessed through empirical methods, their effectiveness can be observed in changes in the partition coefficients of the proteins. The effectiveness of heparanase II was most likely limited by steric hindrance of the 84kDa molecule within the lens capsule matrix.

To assist with lens orientation, epithelial cell nuclei were treated with the vital nuclear stain DRAQ-5™ (0.5µl/ml) (#DR500, Biostatus Ltd., Leicestershore, UK) for a minimum of 20 minutes at room temperature.

4.3. Partition Coefficients and Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

Whole lenses of wild type FVB/N mice (8–12 week old) were placed in #1.5 cover slip dishes containing the solution of fluorescein-labeled dextran or protein of interest in PBS. Labeled molecules were allowed to equilibrate into lens capsules for at least 10 minutes prior to partition coefficient and FRAP experiments. Longer incubation periods did not affect results for molecules described in this study. Fluorescence intensity data for both FRAP and partition coefficient experiments were obtained from images acquired using a 40X C-Apochromat water immersion objective (NA=1.2) on a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 inverted microscope configured as an LSM 5DUO confocal (with both LSM510 META and LSM5 LIVE scanheads).

Partition coefficients were determined using the fluorescence intensity data from X-Y plane confocal images of the anterior lens capsule at a distance of 50µm from the cover slip. The fluorescence intensity ratio averaged from 50 consecutive points from within the middle of the capsule and 50 consecutive points from the surrounding media was used to determine a partition coefficient.

FRAP experiments were performed along the X-Y plane within the anterior lens capsule at a depth of 6µm. A 2.5µm radius circular region of interest (ROI) was chosen at random in the center of the anterior capsule and average fluorescence intensity data was acquired from confocal images at a rate of 20 fps. A 100mW 488 diode laser was directed from the META scanhead via an 80/20 mirror to bleach the ROI, while all image acquisition utilized the 5LIVE scanhead with a 495 long pass emission filter. Ten pre-bleach images were acquired prior to bleaching the ROI for 50ms (100% laser power) followed by 350 or 1000 post-bleach images for dextran and protein experiments, respectively. The number of images taken after photobleaching the ROI was determined as the effective completion of fluorescence recovery and allowed comparable immobile fraction results for each type of molecule, dextrans and proteins. Each series of FRAP experiments were performed on three or four lenses from five or six different ROIs from each lens.

4.4. Recovery Curve Fitting and Variable Evaluation

A diffusion-reaction model was developed to describe tracer concentration after photobleaching in an infinite homogenous domain. In this model, the fractions that bind to the lens ECM (immobile) and that freely diffuse in the aqueous solution within the porous lens ECM (mobile) are explicitly considered. The binding and dissociation between the two states are assumed to follow first-order reaction kinetics with linear association rate constants (kd and ka). A third reaction term kb is added to describe the loss of fluorescence for both immobile and mobile fractions due to inherent bleaching of the fluorescent signal during the post-bleach image acquisition. The spatiotemporal distribution of the fluorescence in the studied domain is thus described as the following equations:

| (1a, 1b) |

where t is time immediately after photobleaching; Fm and Fi are the fluorescence intensities from mobile and immobile molecules, respectively; D is the diffusion coefficient of the mobile fraction; kd and ka are the kinetic dissociation and association rate constants; and kb is the rate of autofading during continuous recording. The coupled equations (1a and 1b) were analytically solved using the following initial and boundary conditions: i) the photobleached circular spot where intensity is lowered by a factor of κ is created instantaneously at time 0 under 100% laser power; ii) the concentrations at the infinite boundary remain constant.

The detailed derivation of the analytical solution can be found in the document “Characterizing Molecular Diffusion in the Lens Capsule” from the 23rd Annual Workshop on Mathematical Problems in Industry, June 11–15, 2007, University of Delaware, Newark, DE (75). A Matlab script was created to run iterative curve fittings. The function fminsearch provided in the Matlab toolbox was used to identify the free parameters (D, kd, ka, kb) that best fit the predicted fluorescence intensities in the experimental recordings. The goodness of the fitting was examined by the root-mean-square deviation. The initial estimate values were arbitrarily set to be D = 1 µm2/s; kd/ka = 0.01; ka = 0.1; and kb was chosen to be the exponential decay of the pre-bleach recording. Our analysis found that the final optimized parameters were not sensitive to the initial values and they always converged to the optimized values regardless of the initial estimate.

4.5. Determining Permeability

From a molecule’s partition and diffusion coefficients, the permeability (P) of the entire capsule to the molecule can be evaluated using (46):

| (2) |

where Φ is the molecule’s partition coefficient; D is its diffusion coefficient within the capsule; and δ is the thickness of the capsule, approximately 10µm for young FVB/N mice (4). The physical meaning of the P indicates the amount of diffusive flux (J) of solute per unit surface area (A) of the lens capsule per unit concentration difference between inside and outside of the lens capsule (ΔC) (i.e., J/A = PΔC).

4.6. Determining Diffusion Coefficients and Stokes Radii in Solution

To determine diffusion coefficients in solution, FRAP experiments were performed on dextrans and proteins in PBS. Their half recovery times (time when half the initial photobleaching had recovered within the ROI) were determined using the kinetic analysis function in the Zeiss LSM AIM Software (Rel 4.2). The classic Axelrod model (51) was then used to calculate diffusion rates:

| (3) |

where r is the radius of the photobleached region of interest (ROI) which we established as 2.5nm; γD is a factor accounting for the shape of the laser beam (0.88 for circular beams); τ1/2 is the half recovery time. A molecule’s Stokes radius was then estimated using the Stokes-Einstein equation (76):

| (4) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant (1.38×10−23 J · K−1), T is room temperature (298 K), n is the viscosity of PBS assumed to be that of sea water (1.06×10−3 kg · m−1s−1), and Dfree is the molecule’s diffusion coefficient in PBS.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined using single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), with p< 0.05 indicating a significant difference. All error bars represent standard error.

4.8. Helium Ion Microscopy

Whole lenses were washed in 10mM octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside for 60 minutes and then fixed in a 0.08M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4, 1.25% glutaraldehyde, 1% paraformaldehyde solution for about 2 hrs. Fixed lenses were then washed in ddH2O (3 × 10 minutes) then placed in a 1% osmium tetroxide solution for 3 hours. The lenses were again washed in ddH2O (3 × 10 minutes) and then serially dehydrated in 25%, 50%, 75%, 80%, 95%, and 100% ethanol. Dehydrated lenses were then placed in a critical point drier for 3 hours and kept desiccated until imaged.

Helium ion microscopy (HIM) was performed on an Orion Plus (Carl Zeiss SMT). HIM is noted for its improved surface imaging compared to scanning electron microscopy and detailed theoretical and practical aspects of utilizing a helium ion source for imaging can be found in the literature (77,78). No cleaning or coating was employed to the prepared lenses. Lenses were mounted with carbon conductive adhesive tabs to SEM stubs and HIM was carried out at a primary beam energy of 29.5 keV with a beam current of 0.3–0.4 pA. Secondary electron images were acquired with an off-axis Everhardt-Thornley detector. Top-down and tilted view (40 degrees) imaging was employed to facilitate visualization of the porous topology of the sample surface. Due to the insulating nature of our biological samples, a low energy (1 keV) electron flood beam was used to dissipate charge build-up during imaging. This process of charge neutralization was accomplished by multiplexing between the imaging operation and a diffuse electron flood pulse at the beginning of each scan line.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY015279 to MKD, a Sigma-Xi/National Academy of Sciences research award and a GK-12 fellowship both awarded to BPD, a Beckman Young Scholars Fellowship to TPP, National Eye Institute grant EY010535 to JP, NIH COBRE program grant P20RR016459, NIAMS grant AR054385 and University of Delaware Research foundation grants to LW. INBRE program grant P20 RR16472 supported the University of Delaware Bio-Imaging Center. The Authors would also like to thank Chuong Huynh, Larry Scipioni, and Arno Merkle (Carl Zeiss SMT, Inc., Peabody, MA) for their assistance with the helium ion microscopy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beyer TL, Vogler G, Sharma D, O'Donnell FE., Jr Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotlier E, Fox J, Bohigian G, Beaty C, Du Pree A. Nature. 1968;217:38–40. doi: 10.1038/217038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karkinen-Jaaskelainen M, Saxen L, Vaheri A, Leinikki P. J Exp Med. 1975;141:1238–1248. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.6.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danysh BP, Czymmek KJ, Olurin PT, Sivak JG, Duncan MK. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:1619–1627. doi: 10.1002/ar.20753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danysh BP, Duncan MK. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker J, Menko AS. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cammarata P, Cantu-Crouch D, Oakford L, Morrill A. Tissue Cell. 1986;18:83–97. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(86)90009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi M, Morita H, Sormunen R, Airenne S, Kreivi M, Wang L, Fukai N, Olsen B, Tryggvason K, Soininen R. EMBO J. 2003;22:236–245. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yurchenco PD, Amenta PS, Patton BL. Matrix Biol. 2004;22:521–538. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CH, Hansma HG. J Struct Biol. 2000;131:44–55. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurie GW, Bing JT, Kleinman HK, Hassell JR, Aumailley M, Martin GR, Feldmann RJ. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krag S, Andreassen TT. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:749–767. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yurchenco P, Schittny J. FASEB J. 1990;4:1577–1590. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.6.2180767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groffen AJ, Ruegg MA, Dijkman H, van de Velden TJ, Buskens CA, van den Born J, Assmann KJ, Monnens LA, Veerkamp JH, van den Heuvel LP. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:19–27. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohan P, Spiro R. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4328–4336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haraldsson B, Nystrom J, Deen WM. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:451–487. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4108–4113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730776100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fels IG. Exp Eye Res. 1970;10:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(70)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher RF. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1977;97:100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedenwald JS. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1930;28:195–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson ML. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:726–740. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tholozan FM, Gribbon C, Li Z, Goldberg MW, Prescott AR, McKie N, Quinlan RA. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4222–4231. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanwar YS, Farquhar MG. J Cell Biol. 1979;81:137–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.81.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanwar YS, Farquhar MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:1303–1307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landemore G, Stefani P, Quillec M, Lecoq-Guilbert P, Billotte C, Izard J. Histochem J. 1999;31:161–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1003598919867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster EH, Jr, Searls RL, Hilfer SR, Zwaan J. Anat Rec. 1987;218:329–337. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092180314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkler J, Wirbelauer C, Frank V, Laqua H. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72:311–318. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanwar YS, Linker A, Farquhar MG. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:688–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parthasarathy N, Spiro RG. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;213:504–511. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedenwald J. Arch Ophthalmol. 1930;3:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bray J, Robinson GB. Kidney Int. 1984;25:527–533. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comper WD, Tay M, Wells X, Dawes J. Biochem J. 1994;297(Pt 1):31–34. doi: 10.1042/bj2970031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo LM, Bakris GL, Comper WD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:899–919. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farquhar MG. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2090–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI29488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delamere NA, Duncan G. J Physiol. 1979;295:241–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozaki L. J Am Intraocul Implant Soc. 1984;10:182–184. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(84)80105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinsey VE, Reddy DV. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965;4:104–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CJ, Vroom JA, Fishman HA, Bent SF. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1670–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher RF. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;216:475–496. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeguchi N, Nakagaki M. Biophys J. 1969;9:1029–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(69)86434-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyle DL, Carman P, Takemoto L. Mol Vis. 2002;8:226–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabah JR, Davidson H, McConkey EN, Takemoto L. Mol Vis. 2004;10:254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan Q, Clark JI, Wight TN, Sage EH. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2747–2756. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.13.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messina-Baas OM, Gonzalez-Huerta LM, Cuevas-Covarrubias SA. Mol Vis. 2006;12:995–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards A, Deen WM, Daniels BS. Biophys J. 1997;72:204–213. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chu CL, Goerges AL, Nugent MA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12203–12213. doi: 10.1021/bi050241p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreuger J, Jemth P, Sanders-Lindberg E, Eliahu L, Ron D, Basilico C, Salmivirta M, Lindahl U. Biochem J. 2005;389:145–150. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamanna WC, Kalus I, Padva M, Baldwin RJ, Merry CL, Dierks T. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:290–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uchimura K, Morimoto-Tomita M, Bistrup A, Li J, Lyon M, Gallagher J, Werb Z, Rosen SD. BMC Biochem. 2006;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Axelrod D, Koppel DE, Schlessinger J, Elson E, Webb WW. Biophys J. 1976;16:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertolatus JA, Hunsicker LG. Lab Invest. 1987;56:170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bridges CR, Jr, Rennke HG, Deen WM, Troy JL, Brenner BM. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991;1:1095–1108. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V191095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morita H, Yoshimura A, Inui K, Ideura T, Watanabe H, Wang L, Soininen R, Tryggvason K. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1703–1710. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004050387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Denis HM, Brooks DE, Alleman AR, Andrew SE, Plummer C. Vet Ophthalmol. 2003;6:321–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2003.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW. Dev Biol. 2005;280:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabah J, McConkey E, Welti R, Albin K, Takemoto LJ. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabah JR, Schultz BD, Brown ZW, Nguyen AT, Reddan J, Takemoto LJ. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1237–1244. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harned J, Fleisher LN, McGahan MC. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tencer J, Frick IM, Oquist BW, Alm P, Rippe B. Kidney Int. 1998;53:709–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Venturoli D, Rippe B. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F605–F613. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00171.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chua BA, Perks AM. J Physiol. 1998;513(Pt 1):283–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.283by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Curiel D, Douglas JT. Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. Boston: Academic Press, Amsterdam; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robertson JV, Nathu Z, Najjar A, Dwivedi D, Gauldie J, West-Mays JA. Mol Vis. 2007;13:457–469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori S, Barth HG. Size exclusion chromatography. New York: Springer, Berlin; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pande A, Banerjee PR, Patrosz J, Pande J. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50 E-abstract 1640. [Google Scholar]

- 67.MathWorks. Matlab Bioinformatics Toolbox, v3.1 (R2008a) Natick, MA: MathWorks Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pande A, Pande J, Asherie N, Lomakin A, Ogun O, King JA, Lubsen NH, Walton D, Benedek GB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1993–1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040554397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duan X, Lu Q, Xue P, Zhang H, Dong Z, Yang F, Wang N. Mol Vis. 2008;14:370–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Funding M, Vorum H, Honore B, Nexo E, Ehlers N. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu JH, Lindsey JD, Weinreb RN. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bertolatus JA, Klinzman D. Microvasc Res. 1991;41:311–327. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Linhardt RJ, Turnbull JE, Wang HM, Loganathan D, Gallagher JT. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2611–2617. doi: 10.1021/bi00462a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Konidala P, He L, Niemeyer B. J Mol Graph Model. 2006;25:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edwards DA, Duncan MK, Danysh BP, Czymmek KJ, Patel TP, Anthony A, Breward C, Gratton M, Haider M, Joshi Y, Milgrom T, Pelesko J, Schleiniger G, Ziao Z. Twenty Third Annual Workshop on Mathematical Problems in Industry. Newark, DE: University of Delaware; 2007. Characterizing Molecular Diffusion in the Lens Capsule. http://www.math.udel.edu/~edwards/download/pubdir/pubo20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Truskey GA, Yuan F, Katz DF. Transport phenomena in biological systems. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morgan J, Notte JA, Hill R, Ward BW. Microscopy Today. 2006;14:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ward BW, Notte JA, Economou NP. Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B. 2006;24:2871–2874. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.