Abstract

Objective

The present experiments were conducted to explore the role of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, potential upstream regulators of MMPs, in abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs).

Methods

Rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs) from males and females were treated with media containing interleukin (IL)-1β (2 ng/mL), a concentration known to be present in AAAs. Levels of both total and phosphorylated (activated) extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun amino terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK), and p38 were examined by Western blotting at various time intervals up to 60 minutes. Similar experiments were conducted following exposure of RASMCs to elastase (6 U/mL), a concentration known to induce AAA formation in rodents. Finally, media was assayed for MMP activity by zymography.

Results

Total ERK (t-ERK) was consistently no different in females compared to males prior to or following IL-1β exposure. In contrast, levels of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) were significantly higher in males than females throughout the post-exposure period (P < 0.0001). Levels of t-p38, p-p38, and t-JNK were not altered in a gender-dependent manner, and the lack of p-JNK levels detected in both male and female RASMCs did not allow for conclusions to be drawn regarding gender disparities in this pathway. Results were similar following RASMC elastase exposure, although t-ERK levels were consistently higher in females than males (P < 0.0001). pro-MMP2 levels were significantly higher (P = 0.0035) in males than females at each time point following elastase exposure.

Conclusions

These data provide evidence implicating alterations in p-ERK signaling via the up-regulation of MMPs as a potential explanation for gender-related discrepancies in AAA formation.

Keywords: MMP, MAPK, ERK, aorta, smooth muscle cells, abdominal aortic aneurysm

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) affect 6–9% of men over 65 years of age and comprise the 10th leading cause of death in males over the age of 55.1 Currently, there are no medical therapies available to treat patients with aortic aneurysms, which are often deadly when they rupture after progressive expansion. In addition, it has long been observed that the incidence of human AAAs is significantly greater in males than in females.2 Thus, there exists a need to define and understand the early mechanisms by which AAAs form, as gender disparities in AAA formation may hold the key to determining potential therapeutic targets.

Recent work by Yoshimura et al. revealed that protein kinases in the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) family may play a significant role in increasing MMP9 activity, known to be critical in the pathogenesis of AAA formation.3 The MAPK family includes three protein kinases: 1) p38, 2) c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK), and 3) extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). The activation cascade of ERK in particular has been shown to induce MMP9 expression.4,5 Additional studies have implicated ERK activation as being critical to the inflammatory response by promoting neutrophil transmigration as well as by inducing proinflammatory cytokines in human vascular cells.6,7

Our laboratory recently showed that MMP2 and MMP 9 are expressed at significantly higher levels in male RASMCs than female RASMCs after IL-1β exposure.2,8 Given the proposed association between MAPK proteins, MMPs, and AAA development, as well as the established gender differences in AAA formation, the present investigation tested the hypothesis that the differential activation of MAPK proteins may contribute to gender-related differences in aortic smooth muscle MMP induction. Experiments in RASMCS in the setting of elastase exposure, at concentrations known to induce AAAs in rodents, were also performed. Finally, media from RASMCs following elastase exposure was assayed for the presence of MMP2, an enzyme known to be constitutively expressed by vascular SMCs.9 No assay was performed for the presence of MMP9 in this experiment because it has been observed in previous experiments in our laboratory that it takes at least 6 hours for MMP9 to be up-regulated following elastase exposure (data not shown).

Methods

Cell Culture

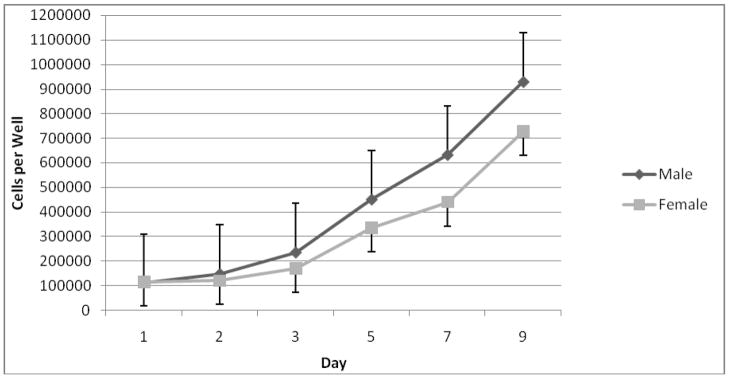

Reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated. All experiments were performed with approval of the University of Michigan Committee on Laboratory Animal Medicine. RASMCs were cultured from the abdominal aortas of young (190–210 g) male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Labs, MA). After animal sacrifice and aortic explantation under general inhalational anesthesia, the aortic tissue was cut into 2 mm2 pieces and placed in 60 mm diameter plastic tissue culture dishes. Basement membrane Matrigel (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA) was applied to each section of explanted tissue to prevent floating. Cultures were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and glutamine 292 mcg/mL. Tissue culture media and antibiotics were obtained from Gibco (Rockville, MD). Tissues were incubated at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 to 7 d, until spindle-shaped SMC were observed extending from the tissue. After removing the explant, cells were dispersed by treatment with trypsin (Gibco), centrifuged, resuspended in complete medium, and placed into 75 cm2 culture flasks. Postconfluent cultures assumed a hill and valley topography characteristic of SMCs grown in vitro. RASMCs were confirmed by staining with a monoclonal antibody against SMC-specific α-actin and determined to nearly 100% SMCs. The rate of proliferation of male and female RASMCs was then measured using a Coulter Z1 Series particle counter from Beckman Coulter (Miami, FL) between days 1–9, and male SMCs were found to proliferate at a significantly higher rate than female SMCs (P < 0.05) (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cell proliferation rates by gender. As measured by Coulter counter on days 1–9. P < 0.05, indicating that male RASMCs proliferate at a significantly higher rate than female cells.

Experimental Groups

Adult male and female RASMCs were isolated and grown in phenol red free DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. Confluent monolayers of RASMCs at passages 4 through 8 were stimulated in serum-free media with interleukin (IL)-1β at concentrations encountered in human aortic aneurysms (2 ng/mL).10 At time points 0, 3, 5, 10, 30, and 60 minutes following IL-1β exposure, cultured media was collected and subsequently assayed for the presence of t-ERK, p-ERK, t-JNK, p-JNK, t-p38, and p-p38 by Western blotting. Similar experiments with the same time points of exposure were subsequently performed using porcine pancreatic elastase (6 U/mL) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at concentrations known to induce AAAs in rodents.11 Media was also assayed for MMP activity by zymography following timed elastase exposure.

Western Blot Analysis

Electrophoresis and Western blotting supplies were obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA). Equal volumes of media from IL-1β-stimulated or elastase-treated RASMC cultures were electrophoretically separated on a 7.5% acrylamide gel and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating the membrane overnight in 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk. The primary antibodies used to assay for each protein at 1:2000 were as follows: for t-ERK, anti-rabbit antibody to p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); for p-ERK, anti-rabbit antibody to phospho-p44/42 (Cell Signaling); for t-JNK, anti-rabbit antibody to t-JNK (Cell Signaling); for p-JNK, anti-rabbit antibody to phospho-JNK (Cell Signaling); for t-p38, anti-rabbit antibody to t-p38 (Cell Signaling); and for p-p38, anti-rabbit antibody to phospho-p38 (Cell Signaling). Anti-rabbit and anti-biotin were used as secondary antibodies in each of these experiments (Cell Signaling). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an ECL chemiluminescence detection kit from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ), and the amount of protein (corrected to total cellular protein) was measured by densitometry.

Substrate Gel Zymography

Zymography supplies were purchased from Novex (San Diego, CA). MMP distribution after treatment of RASMC with IL-1β (or elastase) at time points of 0, 3, 5, 10, 30, and 60 minutes. Gelatin substrate zymograms were prepared using precast 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg/mL of gelatin. Equal volumes of experimental media samples were diluted into 2X tris-glycine SDS sample buffer and electrophoretically separated under non-reducing conditions. Proteins were renatured in 2.7% Triton X-10 and the gels were developed overnight at 37°C in 50 mM tris-HCl containing 5 mM CaCl2 and 2% Brij 35. Following overnight staining with Coomassie blue R-250 and de-staining for 4 h with 10% acetic acid and 40% methanol in water, gelatinase activity was evident by clear bands against a dark blue background.

Densitometry

All gel images were acquired using a FOTO/Analyst CCD CAMERA from Fotodyne (Hartland, WI). Band strength was quantified using GEL-Pro Analyzer software version 3.1 from Media Cybernetics (Silver Spring, MD).

Data Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate or quadruplicate with an N=3 or 4 at each time point. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine differences in t-ERK, p-ERK, t-JNK, t-p38, p-p38 and MMP2 between genders, with P < 0.05 considered significant (no statistical analysis could be performed on p-JNK levels due to its lack of production by both male and female RASMCs). One-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test was used to compare means between different exposure time points, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Statistical calculations were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 3.0a for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

MAPK following IL-1β exposure

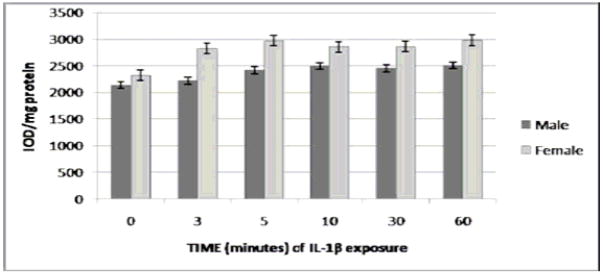

There were no significant differences in t-ERK expression between genders following RASMC exposure to IL-1β as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 2A). There were, however, intrinsic gender-related differences observed between male and female RASMCs following exposure to IL-1β with regard to p-ERK protein expression (Figs. 2B and 2C). At all time points during IL-1β exposure except for the final time point, p-ERK levels (o.d./mg total protein) were significantly higher in males than females (P < 0.0004 overall for cumulative gender differences between 0–60 minutes of IL-1β exposure). Between 0 and 10 minutes of exposure, p-ERK protein expression varied between 1.5-fold (271.4 ± 68.0 versus 179.2 ± 6.8 at 0 minutes) and 2.4-fold (403.8 ± 69.4 versus 168.2 ± 16.4 at 3 minutes) in male versus female RASMCs. pERK expression in both males and females reached its peak at 30 minutes, at which point p-ERK levels were nearly 1.4-fold higher in males versus females (709.5 ± 121.8 versus 517.4 ± 118.2). p-ERK levels for both genders combined demonstrated a strong dependence on exposure time (P < 0.0001) and reached a peak at 30 minutes of exposure before decreasing to levels near baseline at 60 minutes. There were statistically significant differences between total p-ERK levels at 0 versus 10 minutes (P < 0.05), 0 versus 30 minutes (P < 0.05), 10 versus 60 minutes (P < 0.05), and 30 versus 60 minutes (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between males and females in t-JNK, t-p38, and p-38 protein levels following IL-1β exposure (data not shown). p-JNK by Western blot for both male and female RASMCs following exposure to both IL-1β and elastase was undetectable by densitometry in spite of multiple repeated attempts, thereby precluding the possibility of drawing definitive conclusions regarding the potential role of gender in the activation of this pathway.

FIGURE 2.

2A. t-ERK level by gender following exposure to IL-1β. As measured by Western blotting. P = 0.1448 (non-significant; there was no significant overall difference detected in t-ERK expression between genders in the post-exposure period). (N = 4 per group). 2B. p-ERK level by gender following exposure to IL-1β, as measured by Western blotting. P < 0.0004, for overall cumulative gender differences in p-ERK expression in the post-exposure period(N = 4 per group). p-ERK levels for both genders combined were significantly higher at 30 minutes than at baseline (P < 0.05), and significantly lower at 60 minutes than 30 minutes (P < 0.05) and 10 minutes (P < 0.05). 2C. Western blot analysis for both t-ERK and p-ERK in male and female RASMCs at each time point of exposure to IL-1β.

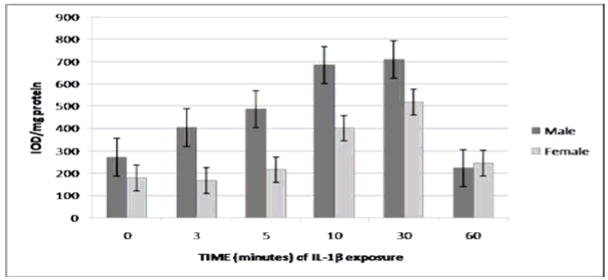

MAPK and MMP2 following elastase exposure

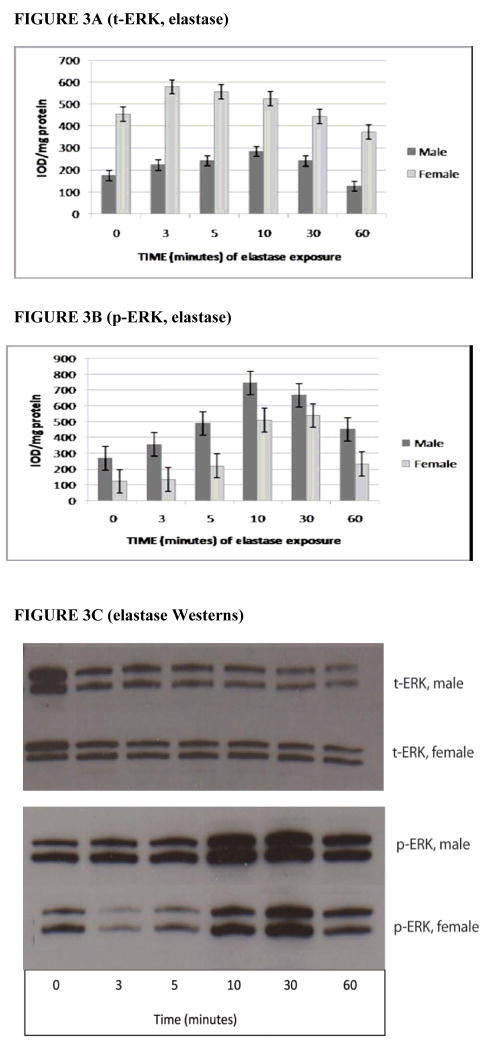

Following elastase exposure, t-ERK levels (o.d./mg total protein) were significantly higher in females than males (P < 0.0001 overall for cumulative gender differences between 0–60 minutes of elastase exposure) (Fig. 3A). This trend was reversed for p-ERK levels, however, with levels of activated ERK being significantly greater in males than females following exposure to elastase (P < 0.0001 overall for cumulative gender differences between 0–60 minutes of elastase exposure) (Figs. 3B and 3C). As in the IL-1β experiment, p-ERK levels from both genders combined displayed a significant time dependence (P < 0.0001 overall), as well as statistically different levels at the same points seen in the IL-1β experiment, with the notable exception that there was no significant difference between 30 and 60 minutes (P > 0.05). This finding suggests that elastase may exert its peak effect on p-ERK levels at an earlier time point than does IL-1β before beginning to decrease.

FIGURE 3.

3A. t-ERK level by gender following exposure to elastase. As measured by Western blotting. P < 0.0001, indicating that female RASMCs express significantly higher cumulative levels of t-ERK overall following elastase exposure than male RASMCs (N = 3 per group). 3B. p-ERK level by gender following exposure to elastase as measured by Western blotting. P < 0.0001 for cumulative overall gender differences in p-ERK expression in the post-exposure period (N = 3 per group). p-ERK levels for both genders combined were significantly higher at 30 minutes than at baseline (P < 0.05) and significantly higher at 10 minutes than 60 minutes (P <0.05) but were not significantly higher at 30 minutes than at 60 minutes (P > 0.05), suggesting an earlier peak effect of elastase on p-ERK levels as compared to IL-1β. 3C. Western blot analysis for t-ERK in male and female RASMCs at each time point of exposure to elastase.

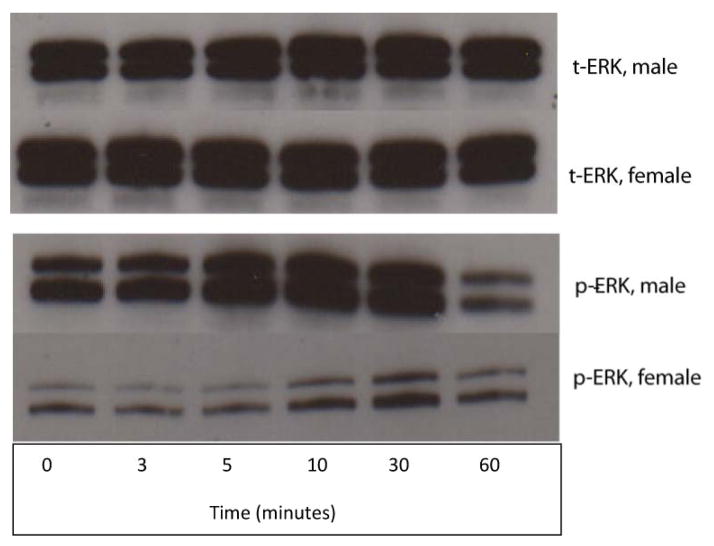

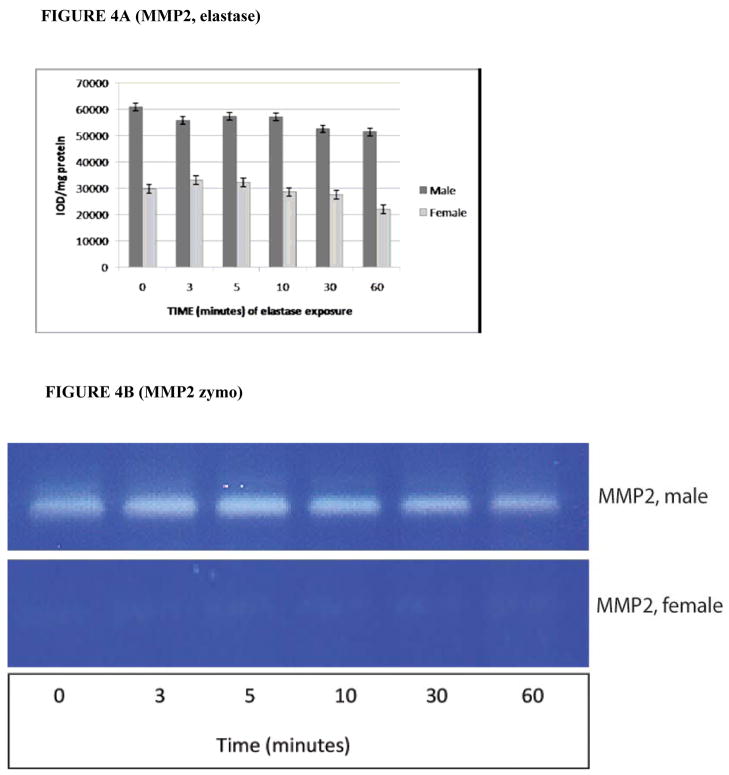

By zymography, pro-MMP2 activity (o.d./mg total protein) was also significantly greater in male RASMCs compared to females, with the ratio of pro-MMP2 activity varying between 1.7 and 2.3 for each time point of elastase exposure (P = 0.0035 overall for cumulative gender differences between 0–60 minutes of elastase exposure, see Figs. 4A and 4B). The mean difference across all time points in pro-MMP2 activity levels between males and females was 55,882.2 ± 1,418.2 versus 28,906.0 ± 1,622.3. There were no significant differences found in the level of pro-MMP2 expressed as a function of time (P = 0.989). As MMP9 is inducible and not constitutively expressed, no MMP9 activity is seen following only 1 hour of IL-1β or elastase exposure (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

4A. pro-MMP2 activity level by gender following exposure to elastase as measured by zymography. P = 0.0035 for cumulative gender differences in Pro-MMP2 expression in the post-exposure period. (N = 3 per group). 4B. Substrate gel zymography analysis for pro-MMP2 levels following timed exposure to elastase at 6 U/mL.

Discussion

There is a significant gender discrepancy in AAA formation, with males being around 4 times as likely to develop this condition during their lifetime as females.12 It follows from this gender disparity that males may possess some pathogenic factors that predispose them to AAA development, or alternatively that females have protective factors that decreases their risk for developing this condition. The search for these factors, whether they be pathogenic or protective, may be pivotal in unraveling the pathogenesis of AAA formation. In the present experiments, it was shown that RASMCs from males contained significantly higher levels of pERK than female RASMCs both at the time of exposure to IL-1β, an interleukin known to be critical in AAA formation, as well as throughout the first thirty minutes of exposure. This same finding was also seen upon exposure of RASMCs to elastase, an enzyme known to induce AAA formation in rodents. The up-regulation of p-ERK following elastase exposure was particularly striking given that females had significantly higher levels of t-ERK levels than males in the elastase experiment, which was not the case in the IL-1β experiment.

Interestingly, the up-regulation of p-ERK decreased progressively by 60 minutes of exposure to either IL-1β or elastase after increasing steadily up to 30 minutes and 10 minutes respectively, suggesting that the peak level of ERK activation occurs somewhere between 30–60 minutes for IL-1β and 10–60 minutes for elastase before dropping off. The former result is consistent with Wuyts et al.’ s finding that IL-1β induces peak ERK phosphorylation in SMCs between 15–30 minutes of exposure before decreasing to levels comparable to baseline at 60 minutes.13 Futhermore, the latter result coincides with Chen et al.’s experiment showing that both t-ERK and p-ERK are highly up-regulated in lung epithelial cells within 10 minutes of elastase stimulation in vitro,14 suggesting that elastase rapidly affects protein synthesis in the in vitro setting. This rapid up-regulation of ERK following elastase exposure is also consistent with Murr et al.’s finding that ERK activation in Kuppfer cells reaches a peak at 15 minutes of elastase exposure before progressively decreasing until the 60 minute mark.15 Given this time-dependent pattern in ERK activation by both IL-1β and elastase, it is not surprising that the effect of gender difference in p-ERK expression is decreased by 60 minutes in conjunction with this decreased overall activation of p-ERK after a relatively early peak.

One of the critical groups of enzymes involved in AAA formation is the MMPs. For example, MMP9, also known as gelatinase-B is consistently elevated in the walls of human AAAs and the serum of AAA patients. In addition, MMP9 knockout mice do not form experimental aneurysms.2,16 Similar findings for MMP2 have been demonstrated.17 It follows that any substance that induces MMP9 or MMP2 activity may therefore contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of AAA formation.

p38, JNK/SAPK, and ERK are all members of the MAPK family that have been shown to be associated with MMP9 up-regulation and subsequent AAA formation in previous studies.3 In particular, Yoshimura et al. found that human AAA tissue showed high levels of p-JNK and that selective inhibition of JNK in vivo both prevented AAA development and led to regression of established AAAs in mouse models. The purpose of the present experiments was to determine whether RASMCs from male and female rodents would have altered concentrations of any of the MAPKs studied. ‘In the present study, the ERK signaling pathway was the sole pathway that was up-regulated in a gender-dependent manner in RASMCs exposed to IL-1β or elastase. It should be noted, however, that assays for the activated form of JNK (p-JNK) were inconclusive and should be re-examined in future work, especially in light of Yoshimura et al.’s findings regarding the significance of the up-regulation of this pathway in the pathogenesis of AAAs.3 Combined with the results of significantly increased levels of p-ERK in male RASMCs as opposed to female RASMCs, these data suggest that stimulation of the ERK activation cascade may contribute to AAA formation, as well as contribute to the gender disparity in AAA formation. The results document that pro-MMP2 activity is also increased following timed exposure to elastase, suggesting an association with p-ERK activation and increased MMP2 activity.

The gender-dependent differences in the expression of p-ERK en route to AAA formation may now join a growing list of factors previously identified to possibly account for the significant disparity in AAA formation between men and women. Our laboratory found that experimental aneurysms in male rodents had more significant macrophage infiltrates and increased MMP9 production and activity than female AAAs.2,18 We have also shown that MMP2 is higher in male RASMCs compared to female RASMCs upon exposure to IL-1β,8 a finding that prompted the investigation in the present study into whether pro-MMP2 is up-regulated in a gender-dependent manner following RASMC elastase exposure. Recent work by Wu et al. reinforces our hypothesis that estrogen may serve as a protective factor against AAA formation in females by decreasing the synthesis of both MMP2 and MMP9.16,19 Several studies have linked p-ERK to the up-regulation of MMP9,4,5 and exploring this connection within the context of AAA formation as well as determining whether p-ERK triggers MMP2 activity will be important projects to pursue in the future.

There are several important limitations in this present study that should be addressed in further work on this topic. First, this investigation was performed solely in vitro and carried out as an acute experimental set-up in which a one-time stimulation of RASMCs was accompanied by a relatively short period of follow-up. The nature of this experiment thus differs substantially from the in vivo setting, in which exposure to serum and tissue factors occurs chronically and changes occur over a much longer period of time. Future experiments should seek to examine this hypothesis in in vivo models of AAA formation, as well as in human aortic samples. Current work in our laboratory is focused on using in vivo models in both genetic ERK1 knockout mice, as well as pharmacological inhibitors of ERK and its activator, Mitogen-Activating ERK-regulating Kinase (MEK), to assess whether p-ERK is up-regulated in mouse AAAs following elastase perfusion of the abdominal aorta. Furthermore, the mechanisms by which the ERK activation cascade is triggered, as well as the role of p-ERK in up-regulating the MMPs, known to be critical in AAA formation must be explored. Finally, the role of the MAPKs in monocyte/macrophage activation during AAA formation should also be the focus of further work.

In conclusion, p-ERK protein levels were significantly increased in RASMCs following exposure to either IL-1β or elastase at levels known to be critical to AAA formation, and were also significantly higher in males compared with female RASMCs. Neither t-p38, p-p38, nor t-JNK were altered in a gender-dependent manner during these experiments, and no conclusions regarding a role for gender in the JNK/SAPK pathway can be drawn from this experiment as a result of the lack of p-JNK levels detected by densitometry.. These data provide preliminary evidence implicating alterations in p-ERK signaling via the up-regulation of MMP2 as a potential explanation for gender-related discrepancies in AAA formation.

Acknowledgments

NIH 5R01(HL081629-02), the Jobst Foundation, NIH-NIA 5 T35 AG02368, the University of Michigan Medical School Student Biomedical Research Program, and the American Vascular Association Lifeline Student Research Fellowship.

References

- 1.Curci JA, Lee JK, Thompson RW. Pathogenesis of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Curr Ther Vasc Surg. 2001:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodrum DT, Ford JW, Ailawadi G, Pearce CG, Sinha I, Eagleton MJ, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr Gender differences in rat aortic smooth muscle cell matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(3):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimura K, Aoki H, Ikeda Y, Fujii K, Akiyama N, Furutani A, Hoshii Y, Tanaka N, Ricci R, Ishihara T, Esato K, Hamano K, Matsuzaki M. Regression of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Nat Med. 2005;11:1330–1338. doi: 10.1038/nm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arai K, Lee S, Lo EH. Essential role for ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase in matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulation in rat cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2003;43(3):254–264. doi: 10.1002/glia.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon S, Cha B, Kim C. ERK1/2 mediates TNF-alpha-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells via the regulation of NF-kappaB and AP-1: Involvement of the ras dependent pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198(3):417–427. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein BN, Gamble JR, Pitson SM, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y. Activation of endothelial extracellular signal-regulated kinase is essential for neutrophil transmigration: potential involvement of a soluble neutrophil factor in endothelial activation. J Immunol. 2003;171(11):6097–6104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minamino T, Yoshida T, Tateno K, Miyauchi H, Zou Y, Toko H, Komuro I. Ras induces vascular smooth muscle cell senescence and inflammation in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;108(18):2264–2269. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093274.82929.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodrum DT, Ford JW, Cho BS, Hannawa KK, Stanley JC, Henke PK, Upchurch GR., Jr Differential effect of 17-β-estradiol on smooth muscle cell and aortic explants MMP2. J Surg Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowther M, Goodall S, Jones JL, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells cultured from abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:575. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.108010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis VA, Persidskaia RN, Baca-Regen LM, et al. Cytokine pattern in aneurismal and occlusive disease of the aorta. J Surg Res. 2001;101:152. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha I, Pearce CG, Cho BS, Hannawa KK, Roelofs KJ, Stanley JC, Henke PK, Upchurch GR., Jr Differential regulation of the superoxide dismutase family in the rodent aneurysm model and rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Surg Res. 2004;121(2):302. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh K, Bonaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjork L, Solberg S. Prevalence and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population based study the Tromso study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(3):236–244. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Modulation by cAMP of IL-1β-induced eotaxin and MCP-1 expression and release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:220–226. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00112002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen HC, Lin HC, Liu CY, Wang CH, Hwang T, Huang TT, Lin CH, Kuo HP. Neutrophil elastase induces IL-18 synthesis by lung epithelial cells via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biomed Sci. 2004;11(1):49–58. doi: 10.1007/BF02256548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murr MM, Yang J, Fier A, Gallagher SF, Carter G, Gower WR, Jr, Norman JG. Regulation of Kuppfer cell TNF gene expression during experimental acute pancreatitis: the role of p38-MAPK, ERK1/2, SAPK/JNK, and NF-κB. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(1):20–25. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Upchurch GR., Jr Current concepts in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:584–588. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longo GM, Buda SJ, Fiotta N, Xiong W, Griener T, Shapiro S, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(5):625–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Roelofs KJ, Sinha I, Hannawa KK, Kaldjian EP, Lu G, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Weiss SJ, Thompson RW, Upchurch GR., Jr Gender differences in experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2116. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143386.26399.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu XF, Zhang J, Paskauskas S, Xin SJ, Duan ZQ. The role of estrogen in the formation of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Surg. 2009;197(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]