Abstract

Post-synaptic density protein PSD-95 is emerging as a valid target for modulating nociception in animal studies. Based on the key role of PSD-95 in neuronal plasticity and the maintenance of pain behavior, we predicted that CN2097, a peptide-based macrocycle of 9 residues that binds to the PDZ domains of PSD-95, would interfere with physiologic phenomena in the spinal cord related to central sensitization. Furthermore, we tested whether spinal intrathecal injection of CN2097 attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a rat model of sciatic neuropathy. Results demonstrate that spinal CN2097 reverses hyperexcitability of WDR neurons in the dorsal horn of neuropathic rats and decreases their evoked responses to peripheral stimuli (brush, low caliber von Frey and pressure), whereas CN5125 (‘negative control’) has no effect. CN2097 also blocks C-fiber LTP in the dorsal horn, which is linked to neuronal plasticity and central sensitization. At a molecular level, CN2097 attenuates the increase in phosphorylated p38 MAPK, a key intracellular signaling pathway in neuropathic pain. Moreover, spinal injection of CN2097 blocks thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic rats. We conclude that CN2097 is a small molecule peptide with putative anti-nociceptive effects that modulates physiologic phenomena related to central sensitization under conditions of chronic pain.

Introduction

Protein-protein interactions that are critical for normal and pathological signal transduction pathways have recently become attractive targets for developing therapeutic molecules. In particular, post-synaptic density protein PSD-95 has been identified mainly in dorsal horn laminae I and II, with distinct expression and localization patterns suggesting predominant expression in nociceptive pathways and a key role in pain mechanisms (Garry, et al., 2003, Tao, et al., 2000), though a more recent study indicated widespread expression of PSD-95 at glutamatergic synapses throughout the spinal gray matter (Polgar, et al., 2008). Persistent or recurrent pain caused by nerve damage is referred to as neuropathic, which tends to be mostly intractable (Campbell and Meyer, 2006, Dworkin, et al., 2003) and associated with neuropathic behavior, including thermal hyperalgesia (increased pain evoked by mildly noxious heat) (Treede, et al., 1992). Based on studies using genetic approaches, PSD-95 emerged as an important factor in the maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia, (Tao, et al., 2001, Tao, et al., 2003, Tao, et al., 2000). For example, a synthetic fusion protein of 168 residues, comprising the entire PDZ2 (PSD-95, Discs large, Zona occludens 1) domain of PSD-95, was found to significantly reduce chronic pain behavior in mice following injection of complete Freund's adjuvant in the hindpaw (Tao, et al., 2008). More recently, it was reported that thermal hyperalgesia is attenuated by disruption of the protein-protein interaction between nNOS and PSD95, using a small molecule inhibitor and a cell permeable Tat fusion protein (Florio, et al., 2009). Therefore, PSD-95 is thought to be a novel molecular target for managing chronic pain and several other neuropathologic conditions (Gardoni, 2008, Houslay, 2009, Tao and Johns, 2006, Tao and Raja, 2004).

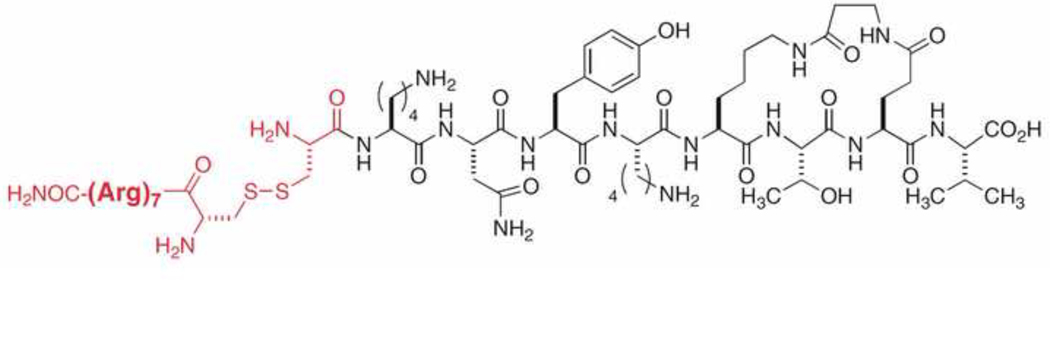

Therefore, with the aim of targeting the PDZ domains of PSD-95, we designed and synthesized compound CN2097 (Fig 1), a ligand directly based on a macrocyclic peptide previously established as capable of binding PDZ3 (Li, et al., 2004) and PDZ1 (Piserchio, et al., 2004) domains of PSD-95. Cell-based evaluation of this precursor macrocyclic peptide demonstrated activity within a PDZ domain-based clustering assay, and also exhibited enhanced longevity of action over a linear peptide control, suggesting added stability imparted by the cyclic structure (Piserchio, et al., 2004). CN2097 was generated by appending a sequence of seven arginines via a Cys-Cys disulfide linkage. This modification was adopted to impart cell permeability, since the use of polyarginine tags has been shown to be effective at delivering attached compounds across cellular membranes (Rothbard, et al., 2000). In addition, we designed CN5125, an analog of CN2097 in which the key binding determinants at positions "0" and "-2" (Val and Thr, respectively, in Fig 1) are both replaced with Gly residues. Glycine at those positions dramatically reduces binding to PDZ domains as determined in previously reported biochemical binding studies (Saro, et al., 2007). CN5125 was thus used as the corresponding ‘negative control’.

Fig 1. Structure of cellular probe CN2097.

Experiments with PDZ domain arrays indicated that the biotinylated analog of the CN2097 precursor selectively binds with only the PDZ1-2 and PDZ3 domains of PSD-95, interacting minimally, or not at all, with the other 94 PDZ domain constructs in the array (Fig 2). Compared to the previously reported Tat fusion proteins that bind PSD-95 and exert anti-nociceptive properties (Florio, et al., 2009, Tao, et al., 2008), CN2097 and its related analogues are relatively much smaller peptides in size, which were designed and synthesized based on a biochemical rationale rather than high throughput protein screening for binding against PSD-95 and/or its partner molecules. In addition, we here investigate some of the putative anti-nociceptive mechanisms of CN2097 at behavioral, cellular and molecular levels.

Fig 2. PDZ domain array.

PDZ domain array probed with the CN5115, a TMR-labeled analog containing the PDZ domain-targeting portion of CN2097 (Arrays provided by Dr. Randy Hall, Emory University).

Because PSD-95 plays a key role in neuronal plasticity, which is a core component of learning and memory (Hata and Takai, 1999, Steiner, et al., 2008), as well as central sensitization under chronic pain conditions (Garry, et al., 2003, Ji and Woolf, 2001, Treede, et al., 1992, Woolf, 2007, Zhang, et al., 2005), we predicted that CN2097 would modulate physiological processes related to central sensitization and long-term plasticity in an animal model of chronic neuropathic pain. Furthermore, we tested the anti-nociceptive effects of CN2097 on thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic rats. Confirming our predictions, our data suggest that CN2097 yields a phenotype with anti-nociceptive functional changes.

Methods

In all experiments, CN2097 (MW 2346) or its inactive analogue CN5125 was dissolved in DMSO and diluted to final concentration in aCSF, such that the final concentration of DMSO was 1% regardless of the compound concentration. Spinal (i.t.) and systemic (i.p.) injections were made in 10 µl and 500 µl volumes, respectively. Rats used were Sprague Dawley, male (250–300 g).

Binding ligand selectivity studies with a PDZ domain array

Composition of array- 96 PDZ domains- was described in (He, et al., 2006). The dry membrane was treated with blocking buffer (0.1% Tween 20, 100 mM NaCl in Super Block Buffer, pH 7.4) overnight at 4 °C in an Omni Tray (Nunc) on a shaker. The membrane was fully submerged in the blocking buffer, then allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h. The blocking buffer was removed and the membrane briefly rinsed with wash buffer (1× PBS), then incubated with CN5115 (a TMR-labeled analog containing the PDZ domain-targeting portion of CN2097; 0.1 mg/ml; 10 ml) with gentle shaking for 1–2 h at room temperature. After incubation, the membrane was washed (3×10 ml of wash buffer (PBS), 10 min per wash) at room temperature, then removed by holding the membrane with forceps and touching the edge against tissue. The membrane was placed between two plastic sheets (the top sheet was gently pressed to remove air bubbles), followed by imaging with a scanner, resulting in the image shown in Figure 2.

Chronic constriction injury (CCI)

The sciatic nerve was exposed after skin incision at the mid-thigh level and blunt dissection of the biceps femoris under deep anesthesia (sodium pentobarbital, 60 mg/kg, i.p.). A modified constriction from the originally described model (Bennett and Xie, 1988) was performed by tying three chromic gut (5-0) ligatures loosely around the nerve 1 mm apart, proximal to its trifurcation (Owolabi and Saab, 2006). After CCI, the overlying muscles and skin were closed in layers with 4-0 nylon sutures and the animal was allowed to recover. Rats were then maintained under the same conditions and fed ad libitum.

Surgical preparation for recording neuronal firing and C-fiber field potentials

Rats were prepared as previously described (Owolabi and Saab, 2006). Each rat was anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and mounted on a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instrument) and laminectomy was made to expose the lumbar segments of the spinal cord and to allow recording from the exposed spinal segments at L4-5 levels. The skin of the hindpaw was shaved in preparation for peripheral stimulation and mapping of the cutaneous receptive field during single-unit recording.

Single-unit extracellular recording

The dura was incised to allow placement of a microelectrode (5 MΩ, A–M Systems, Carlsborg, WA, tungsten-insulated except at the tip) mounted on a stereotactic arm connected to a micropositioner (M2670, Kopf Instruments). Recording is done medially near the dorsal root entry zone up to a depth of approximately 900 µm. Electrical signals were amplified and filtered at 300–3000 Hz (DAM8A; World Precision Instruments), processed by a data acquisition system (CED Micro1401; Cambridge Electronic Design), and stored on a computer to construct peristimulus time histograms for off-line analysis using Spike2 software. The response of a neuron to innocuous brush was used to isolate individual action potentials and to map the receptive field on the ipsilateral hindpaw. For testing evoked activity, six routine natural mechanical stimuli were applied in the following order: Brush, by a cotton applicator to the skin; 3 von Frey filaments (0.6, 8 and 15 g) with enough force to cause buckling of the filament at a regular frequency of 1 application per sec; pressure, by attaching a large arterial clip with a weak grip to a fold of skin (144 g/mm2) and pinch, by applying a small arterial clip with a strong grip to a fold of skin (583 g/mm2). Wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons were identified by their responsiveness to brush, more so to pressure and pinch, and with increasing responses to incrementing strengths of von Frey stimuli. Background discharge was recorded for 40 sec, and stimuli were then applied serially for 20 sec, separated by another 20 sec of spontaneous activity without stimulation. Care was taken to ensure that each stimulus was applied to the primary receptive field, and that isolated units displayed action potentials that remained stable for the duration of each experiment using Spike2 template matching. Firing activity was computed as mean frequency of spikes/20 sec, and evoked responses and afterdischarges were calculated by subtracting the pre-stimulus baseline activity to yield a net increase in discharge rate. Cursors were set at the beginning and the end of the stimulus, and all of the spikes occurring between the cursors were summed. Cursors were also set at the beginning of the trace and after 40 sec (baseline or un-evoked firing), and the spikes occurring during this period were summed to provide a measure of the background activity. The two sums were divided by the respective duration and the resulting averages (spikes/s) subtracted to yield the value attributed to the response (total number of spikes/s in excess of the background activity during the stimulus). Only one neuron was recorded from each rat. CN2097, CN5125 or equivalent volume vehicle was completely soaked in a cotton pledget which was added unto the spinal cord within the vicinity of the recording electrode during recording as previously described (Owolabi and Saab, 2006).

C-fiber field potentials

Following similar procedures for surgical preparation and laminectomy (described above), naïve rats were prepared for tracheal cannulation for assisted respiration by artificial ventilation (Harvard Apparatus) and for jugular cannulation for the administration of a muscle relaxant (0.3 mg/kg pancuronium bromide, i.v.). The sciatic nerve was exposed and dissected free from overlying tissue using blunt scissors. Two silver wire electrodes (0.01 inch diameter, A–M Systems), insulated except for 2 mm at the tips and separated by 2 mm, were bent as hooks to support the sciatic nerve without stretching and used for electrical stimulation distal to the sciatic notch (Saab and Waxman, 2004). The microelectrodes were connected to an Isolated Pulse Stimulator (2100, A–M Systems). Exposed nervous tissue was covered with warm saline (37°C). A single microelectrode was used for recording evoked signals at lumbar L4-5 levels from laminae I–V using the electrophysiology set-up described above. To evoke C-fiber field potentials, single current pulses were delivered through the stimulating electrode at increasing intensities until a first volley of C-fiber latency was recorded and reached maximum amplitude. The area under the C-fiber field potential was calculated as ‘curve area’ (Spike 2, CED) peak-to-peak, whereas latency was computed as time from stimulus artifact to the C-fiber field potential trough. C-fiber field potential areas were measured at 3 min intervals 40 min before and up to 40 min after tetanic stimulation (TS). Values for area and latency were normalized to ‘baseline’ (last stimulation/recording session 3 min before TS). Baseline stimuli consisted of single pulses (0.5 ms, 10 V) every 3 min whereas conditioning stimuli or TS were delivered as trains of multiple pulses (100 Hz, 40 V, 0.5 ms, 400 pulses given in 4 trains of 1 sec duration at 10 sec intervals) (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1997).

Western blot of p38 MAPK and phosphorylated p38 MAPK

Spinal cords at cervical (C3-6) and lumbar (L3-6) levels were exposed after laminectomy in rats day 7 after CCI under deep anesthesia (pentobarbital sodium, 60 mg/kg) and treated with CN2097 (10 nmol) or equivalent volume vehicle for 15 min. Afterwards, the cervical segments and lumbar tissue was immediately extracted and lysed in ice-cold modified RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN)] and protein concentration were determined using the BCA colorimetric assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). 40 µg of total spinal tissue lysate of each sample was added to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol, followed by incubation at 95°C for 10 min. Proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and probed with anti-phospho p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182; 1:2000; #9216S, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [IgG; horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked; 1:2000, #7072-1, Cell Signaling Technology), followed by luminescence detection according to the manufacturer’s protocol (enhanced chemiluminescence, Amersham Life Technologies, Arlington Heights, IL). Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with anti-p38 MAPK antibodies (1:1000; #9212, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-rabbit IgG (HRP-linked; 1:2000, #7074, Cell Signaling Technology). Gels were scanned using an EPSON 4180, and protein bands were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ (v1.34 s, NIH).

Thermal hyperalgesia

Rats with CCI manifest abnormal ipsilateral hindpaw posture in a guarding behavior. Preoperative (baseline) testing began on the day of CCI and performed daily afterwards. Thermal sensitivity was measured by the latency of paw withdrawal reflex in response to a radiant heat source (Dirig, et al., 1997). Animals were placed in Plexiglas boxes on an elevated glass plate under which a radiant heat source (4.7 amps) was applied to the plantar surface of the paw (light source automatically shuts off after 15 seconds to prevent tissue damage). Five stimulations separated by 5 min were averaged for each hindpaw and reported as withdrawal latency. Values obtained from the injured hindpaw were compared to those preoperatively (baseline).

Intrathecal injection

CN2097 or saline were administered spinally via indwelling i.t. catheters as previously described in detail (Hains, et al., 2005). Catheters were implanted 3 days after CCI. In naïve rats, catheters were similarly implanted 3 days after baseline testing in parallel to the CCI group. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (3%) and an incision was made at the back of the neck exposing the atlanto-occipital membrane. The catheter was made of PE10 tubing and inserted 8–8.5 cm for drug delivery to the lumbar (L4-5) segments. Rats used in this study tolerated well this procedure and did not exhibit signs of paralysis or other motor abnormalities. Injections were performed under light anesthesia (isoflurane, 3%); in each injection, a compound was administered in a total volume of 10 µl, followed by 5 µl aCSF ‘flush’.

Extent of tissue penetration upon intrathecal (i.t.) injection

Spinal cord tissue was collected and microscopic images were captured using quantitative fluorescence microscopy specific QiCam Retiga cooled-CCD camera acquiring a 12-bit image at 1392 X 1040 pixels captured with a constant 200 ms exposure. Evans blue dye has an emission/excitation spectra (550/610) similar to that of Texas Red (596/620). Mean Fluorescence Intensity was measured within one representative section at each designated spinal level subtracted from background using ImageJ v1.41e (NIH). Behavioral and physiological changes secondary to CCI are thought to involve central sensitization at the level of the lumbar spinal cord, the region of interest in our study being the major zone of entry of sensory input from the hindpaw dermatomes. Therefore, i.t. injections were delivered through catheters with tips located at the lumbar L4-5 region.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance and paired t-test were used to analyze the effects of CN derivatives or vehicle/control at individual time points before and after treatment in the same rat or between groups of rats. In all tests, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Attenuation of WDR evoked firing

At a single-cell level, we tested whether CN2097 attenuates the firing of WDR neurons in rats with CCI. Extracellular action potentials were isolated from single units (n=6–8 units/group, 1 unit/rat) in the dorsal horn corresponding to laminae I–V at lumbar (L4-5) level. Action potential firing was spontaneous and/or evoked by peripheral stimuli applied on corresponding somatic receptive field areas in the hindpaw. All units recorded increased in firing rate in response to applied stimuli and were thus classified as WDR neurons. Spinally applied CN2097 (10 nmol) decreased the firing of neurons in rats with CCI (one example is shown in Fig 3a). In a separate group (n=6 units/group, 1 unit/rat), neuronal firing patterns remained stable and were not affected by vehicle treatment (data not shown). The mean frequency of evoked responses to brush, low caliber von Frey filament (0.6 g) and pressure stimuli were significantly decreased within 20 min after spinal treatment with CN2097 from 19.9 ± 1.7, 6.3 ± 0.8 and 26.9 ± 4.4 % to 14.1 ± 1.7 %, 4.1 ± 0.6 and 15.9 ± 2.7, respectively (Fig 3b). Spontaneous firing rates, such as baseline discharge and afterdischarge, did not significantly change after CN2097 treatment, and the sizes of the receptive fields corresponding to individual units remained constant throughout each recording experiment in rats with CCI (data not shown). In separate experiments, rats at day 7 after CCI were similarly treated with a non-specific ‘negative control’ peptide CN5125 and WDR neuronal activity was recorded before, during and 30 min after spinal application of CN5125 (10 nmol). However, no difference in the mean firing rate was noted (Fig 4a, b).

Fig 3. CN2097 decreases the firing of WDR neurons.

(a) Representative example showing extracellular firing recorded from a single unit in the dorsal horn (lamina III) one week after CCI, at a time of persistent hyperalgesia. Individual action potentials were recorded and used to generate peristimulus time histograms, which show reproducibility of firing and recording under stable conditions in consecutive recording sessions 10 and 20 min before CN2097 treatment (left panels). Although application of CN2097 does not change the rate of spontaneous firing, evoked responses to several stimuli (e.g. brush, pressure and pinch) decreased 10 and 20 min after treatment with CN2097 (right panels), in addition to attenuation in the sustained discharge within 40 sec after pinch (afterdischarge). Numbers show mean frequency of responses per stimulus (Br, vF, Pr, Pi denote brush, von Frey filaments 0.6, 8 and 15 g, pressure, and pinch). (b) Mean WDR response rates (n=6–8 units, 1 unit/rat d7 after CCI) 10 min before and 20 min after CN2097 application. Responses to brush, low caliber von Frey and pressure stimuli decreased significantly, whereas responses to other stimuli were not significantly changed (* p<0.05). Inset shows estimation of the location of these units in the dorsal horn (laminae I–V) ipsilateral to CCI.

Fig 4. CN5125 (‘negative control’) does not affect the firing of WDR neurons.

(a) Top two traces show representative example of extracellular firing recorded from a single unit in the dorsal horn one week after CCI. Individual action potentials and corresponding peristimulus time histograms are shown at 10 before, and 20 min after CN5125 (10 nmol) treatment in the same unit recorded (Br, vF, Pr, Pi denote brush, von Frey filaments 0.6 g, 8 and 15 g, pressure, and pinch). (b) Mean WDR response rates (n=5 units, 1 unit/rat d7 after CCI) 10 min before and 20 min after CN5125 application (10 nmol). Responses to stimuli were not significantly different.

Reduced C-fiber field potentials

In addition to the decrease in the responsiveness of WDR neurons, we predicted that CN2097 would modulate the enhancement in C-fiber field potential, another physiologic correlate of pain and central sensitization. Spinal treatment with CN2097 (10 nmol) prevented the induction of C-fiber LTP in the lumbar dorsal horn. C-fiber field potentials at lumbar (L4-5) level (laminae I–V) were evoked by supramaximal electric stimulation of the sciatic nerve (one example is shown in Fig 5a). The average latency (139.0 ± 6.5 ms, n=9 rats) matched well with previously documented latency in rats (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1997). Baseline C-fiber field potentials were stable at constant current stimulation before (baseline) and after application of spinal vehicle or CN2097. In representative examples (Fig 5b), traces show stable baseline field potentials and a relative increase in size after high frequency ‘tetanic’ current stimulation (TS), a potentiation phenomenon lasting more than 40 min (thus referred to as LTP). In another rat, field potentials remained stable before and after treatment with CN2097 (10 nmol), and relatively not different in size than post-TS. On average, spinal treatment with CN2097 decreased field potential areas at every time point after TS compared to control, but did not change the latencies (Fig 6). Ten min after TS, the mean area increased by 206.8 ± 40.7 % in vehicle-treated rats (n=3), compared to a significantly lesser level (68.4 ± 30.7 %) in CN2097-treated rats (n=3). Furthermore, the mean area in CN2097-treated rats was not significantly different before and after TS, suggesting LTP was blocked.

Fig 5.

(a) C-fiber field potentials (stimulus artifact and A-fiber field potential truncated, scale 150 ms). (b) CN2097 reduces C-fiber field potentials after conditioning stimuli. Traces show baseline C-fiber field potentials (before conditioning stimuli or TS) and 10 after TS. Note stable baseline and increased responses after TS in control rat (vehicle-treated, left panels) indicating induction of LTP compared to no change before and after TS in CN2097-treated rat (right panels).

Fig 6. CN2097 decreases the area, but not the latency of C-fiber field potentials.

Mean C-fiber field potential areas and latencies were normalized to baseline (3 min before TS). Upper panels show timeline of evoked C-fiber field potentials before and after TS at t=0 (vertical dashed line). Note attenuated elevation in area in CN2097-teated rats compared to control at every time point after onset of TS (n=3 rats/group). Lower panels show values at time points corresponding to baseline and 10 min after TS. Histograms show that, in control group, areas significantly increase after TS (* p<0.05), whereas areas in CN2097-treated rats remain non-significantly different from baseline.

Decreased levels of phosphorylated p38 MAPK

At a molecular level, an increase in phosphorylated p38 MAPK in the spinal cord is known to signal a key cascade event in models of neuropathic pain (Jin, et al., 2003, Tsuda, et al., 2004). Therefore, we tested whether CN2097 attenuates phosphorylation of p38 by measuring the ratio of phospho-p38 MAPK/total p38 MAPK (p-p38/p38). In naïve rats, p-p38/p38 at lumbar levels was similar to that at cervical levels (data not shown). Therefore, cervical segments, which do not receive any major input from primary afferents supplying the dermatome of the injured sciatic nerve, were used as ‘internal control’ for each rat. In rats with CCI, pp38/ p38 increased to 2.3 ± 0.9 compared to 1.0 ± 0.1 (vehicle-treated control) and 0.9 ± 0.3 (CN2097-treated control) (p<0.05) (Fig 7). However, this increase reversed back to near normal levels (0.9 ± 0.2) within 15 min after spinal CN2097 (10 nmol).

Fig 7. CN2097 reverses increased levels of phospho-p38 MAPK in CCI.

Freshly isolated spinal cords from vehicle (aCSF) or CN2097-treated 7-day CCI rats were probed for phosphorylated and total p38 MAPK. (a) Representative immunoblots: Total and phosphorylated p38 MAPK after 15 minutes spinal treatment with CN2097. Western blots shown as representative of three independent experiments (n=6 rats). (b) Densitometric analysis: Ratio of phosphorylated p38 MAPK: total p38 MAPK shown as arbitrary units (* p<0.05).

Attenuation of thermal hyperalgesia

Thermal hyperalgesia is commonly observed in patients with neuropathic pain and manifests in most experimental neuropathic models. After CCI, a decrease in paw withdrawal latencies (PWL) suggested neuropathic behavior. At d7 after CCI, PWLs decreased significantly (p<0.05) from 10.8 ± 0.5 sec (baseline) to 7.0 ± 0.6 sec (Fig 8a). Intrathecal injection of CN2097 (10 nmol, n=5 rats) abrogated thermal hyperalgesia, as evidenced by a reversal in PWL to 13.9 ± 1.5 within 15 min after injection. A follow-up in time shows that the anti-nociceptive effects of CN2097 remained significant 2 hr after injection (12.6 ± 1.7), with hyperalgesia being reestablished after 24 hr (8.9 ± 0.5), though to a lesser extent relative to pre-injection. However, hyperalgesia persisted in rats with CCI treated with 1 nmol CN2097 i.t. (n=5 rats, Fig 8b), with PWLs decreasing significantly from 12.3 ± 0.8 baseline to 8.8 ± 0.4 at d7 after CCI, and remaining significantly decreased at 15 min and 2 hr after injection of CN2097 (8.7 ± 0.7, 9.1 ± 0.4, respectively) compared to baseline. Similarly, thermal hyperalgesia was not reversed in rats treated with 200 nmol CN2097 i.p. (n=6 rats, Fig 8c), with PWLs decreasing significantly from 12.6 ± 0.9 baseline to 8.1 ± 0.1 pre-injection, and remaining significantly decreased at 15 min and 2 hr after injection (8.8 ± 0.5, 7.6 ± 0.5, respectively) compared to baseline. These data suggested that 10 nmol is an effective dose when administered centrally. Of note, CN2097 (10 nmol i.t.) did not alter PWLs in naïve rats (Fig 8d). Using Evans blue to determine the rostrocaudal extent of i.t. diffusion, maximal fluorescent intensity (100%) was observed at lumbar (L4-5) level, corresponding to the distal catheter tip (Fig 8e). Diffusion intensity followed a decreasing gradient away from lumbar levels. In similar experiments, a tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-labeled CN2097 was clearly shown to penetrate within the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Fig 8e, inset photo with arrow). TMR-labeling was detected extracellularly and within cellular profiles, indicating that CN2097 crosses the pia/brain barrier and internalizes intracellularly within the cord.

Fig 8. CN2097 attenuates thermal hyperalgesia.

Compared to baseline, paw withdrawal latencies (PWL) decrease significantly at d7 after CCI. (a) A single injection of CN2097 (10 nmol, i.t.) significantly increases PWLs in rats with CCI for at least 2 hrs post-injection (* p<0.05), demonstrating reversal of thermal hyperalgesia and suggesting that CN2097 is biologically active centrally. However, 1 nmol i.t. (b) and 200 nmol i.p. (c) had no effect on withdrawal latency in rats with CCI, and (d) 1 nmol i.t. did not have an affect in naïve rats. (e) Evans blue dye diffused throughout the spinal cord with maximal dye intensity (100%) within the vicinity of the distal tip of the catheter (L4-5) and decreasing diffusion gradients towards upper cervical levels (C6-7). Photo showing one cell in the spinal cord (arrows) with uptake of the TMR-labeled peptide. Labeling was typically vesicular in appearance and localized within the cytoplasm surrounding nuclear profiles in the grey matter. In general, the variance of soma diameters of the labeled cells indicates that more than one subtype of cells may accumulate the cyclic peptide, and that this modified peptide is effective in crossing the pia/brain barrier. White matter was mostly devoid of labeling (scale 35 µm).

Discussion

In this manuscript, we report that CN2097, which binds the PDZ domains of PSD-95, mitigates several physiologic phenomena known to promote neuronal plasticity and central sensitization, as well as thermal hyperalgesia. It also reverses the increased expression of phosphorylated p38 MAPK, a key signaling molecule related to chronic pain.

Neuropathic pain is caused by pathology or lesion to the nervous system (Campbell and Meyer, 2006, Dworkin, et al., 2003). It is often persistent, clinically intractable, and associated with signs of abnormal sensory qualia such as thermal hyperalgesia (Treede, et al., 1992). While treatment options remain limited, PSD-95 is emerging as a novel target for pharmacological intervention (Gardoni, 2008, Tao and Johns, 2006, Tao and Raja, 2004). CN2097 is a relatively small molecule and contains a non-standard ring structure, which is to a first approximation less likely to experience the deficiencies of protein-sized polypeptides. Previously, Tao et al. reported that Tat-PSD-95 PDZ2 reduced inflammatory pain in a mouse model (Tao, et al., 2008). Compared to CN2097, the Tat peptide is a relatively larger size synthetic fusion protein comprising 168 residues, binding to the C-terminal strands of endogenous partners of PSD-95 PDZ2. It remains unclear whether the Tat-PSD-95 PDZ2 peptide modulates neuronal plasticity or central sensitization, a clinically relevant phenomenon.

One important physiological correlate of chronic pain is central sensitization, which is defined as enhanced responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the CNS to their normal afferent input. Central sensitization has been demonstrated in patients with chronic pain (Campbell, et al., 1988). At the single-cell level, central sensitization manifests in part as aberrant spontaneous or evoked firing of multi-responsive WDR neurons in the dorsal horn in response to peripheral stimuli (Laird and Bennett, 1993, Owolabi and Saab, 2006). When CN2097 (but not its negative control CN5125) was applied spinally to neuropathic rats, it reduced WDR neuronal firing in response to select sensory modalities, suggesting modulation of specific spinal transmission processes that contribute to central sensitization. The mechanisms for selectivity of these effects (for example pressure versus pinch) remain unknown.

Another phenomenon thought to be associated with central sensitization is C-fiber LTP in the dorsal horn, which was completely blocked by CN2097. Hippocampal LTP and learning are impaired in PSD-95 mutant mice, further supporting a relationship between PSD-95 and intracellular signaling leading to long-term plasticity (Migaud, et al., 1998). LTP is a much-studied NMDA-dependant cellular model of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and in pain pathways (Sandkuhler, 2007). It is measured as an increase in extracellularly recorded field potentials, which reflect summation of post-synaptic and mainly monosynaptically-evoked currents (Ikeda, et al., 2003) or potentials in response to a single pre-synaptic action potential (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1997). In vivo C-fiber LTP can be measured for several hours in the superficial spinal dorsal horn in response to high intensity electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve (Ikeda, et al., 2003). Both indicators of central sensitization (single-unit firing and C-fiber LTP) offer the advantage of being measured in the whole animal with intact primary afferents and descending pathways from the brain. In addition, LTP can induce central sensitization and wind-up or temporal summation, which can be related to human psychophysical measures and pain complaints in patients (Arendt-Nielsen, et al., 1995, Koltzenburg, et al., 1994). LTP-inducing conditioning stimuli facilitate action potential firing in WDR neurons (Afrah, et al., 2002) and cause persistent thermal hyperalgesia in the ipsilateral hindpaw (Zhang, et al., 2005).

Our data also demonstrate that CN2097 modulates intracellular signaling by reversing the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK that is elevated under neuropathic conditions. We also show that CN2097 penetrates the cord intracellularly upon spinal application. MAPKs, including p38, are downstream to many pain-related membrane receptors and intracellular kinases. They contribute to central sensitization via post-translational, translational, and transcriptional factors, and are known to be activated in the dorsal horn under chronic pain conditions (Ji and Woolf, 2001). p38 is a stress-activated kinase and its inhibition attenuates nociceptive behavior in models of chronic pain (Jin, et al., 2003, Tsuda, et al., 2004). Furthermore, phosphorylation of p38 is required for the initiation of long-term synaptic plasticity and the maintenance of chronic pain states. Though p38 phosphorylation occurs mostly in glia under neuropathic conditions, it is also known to be up-regulated in neurons within the dorsal horn (Svensson, et al., 2005, Xu, et al., 2007). In future studies, it would be important to determine the mode of action of CN2097 in blocking p38 phosphorylation and the specific cell type(s) targeted by CN2097.

Using genetic approaches, PSD-95 was one of the early MAGUK proteins discovered to be required for the maintenance of nociceptive behavior. Knock-down of PSD-95 attenuates thermal hyperalgesia, which is also attenuated in neuropathic PSD-95 mutant mice, without affecting basal responses to moderately painful or non-noxious stimuli (Tao, et al., 2001, Tao, et al., 2003, Tao, et al., 2000). In line with these observations, our results show that CN2097 attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain when administered spinally at the lumbar spinal cord level. These results were corroborated by data showing modulation of cellular and molecular phenomena in the lumbar dorsal horn linked to pain-related plasticity.

In conclusion, the anti-hyperalgesic affects of CN2097 and its modulation of central sensitization provide converging lines of evidence for its biologic activity at the whole animal level. Protein-protein interactions are central to many biological pathways, including intracellular signaling and cell-surface receptor-ligand interactions. These interactions constitute attractive targets for drug discovery, knowing there are currently no such marketed drugs for chronic pain. Provided additional improvements in design are made to CN2097, longer lasting and more effective anti-nociceptive effects might be achieved. This seems likely since CN2097 is formulated stably like many peptide drugs and, being a relatively small molecule, can be optimized by traditional medicinal chemistry.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Julie Kauer for assistance with electrophysiology. CYS supported by Rhode Island Hospital funds, JM and CYS supported by NIH R21NS061176.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Afrah AW, Fiska A, Gjerstad J, Gustafsson H, Tjolsen A, Olgart L, Stiller CO, Hole K, Brodin E. Spinal substance P release in vivo during the induction of long-term potentiation in dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2002;96:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt-Nielsen L, Petersen-Felix S, Fischer M, Bak P, Bjerring P, Zbinden AM. The effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (ketamine) on single and repeated nociceptive stimuli: a placebo-controlled experimental human study. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:63–68. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006;52:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell JN, Raja SN, Meyer RA, Mackinnon SE. Myelinated afferents signal the hyperalgesia associated with nerve injury. Pain. 1988;32:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dirig DM, Salami A, Rathbun ML, Ozaki GT, Yaksh TL. Characterization of variables defining hindpaw withdrawal latency evoked by radiant thermal stimuli. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;76:183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dworkin RH, Backonja M, Rowbotham MC, Allen RR, Argoff CR, Bennett GJ, Bushnell MC, Farrar JT, Galer BS, Haythornthwaite JA, Hewitt DJ, Loeser JD, Max MB, Saltarelli M, Schmader KE, Stein C, Thompson D, Turk DC, Wallace MS, Watkins LR, Weinstein SM. Advances in neuropathic pain: diagnosis, mechanisms, and treatment recommendations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1524–1534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.11.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florio SK, Loh C, Huang SM, Iwamaye AE, Kitto KF, Fowler KW, Treiberg JA, Hayflick JS, Walker JM, Fairbanks CA, Lai Y. Disruption of nNOS-PSD95 protein-protein interaction inhibits acute thermal hyperalgesia and chronic mechanical allodynia in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:494–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardoni F. MAGUK proteins: new targets for pharmacological intervention in the glutamatergic synapse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garry EM, Moss A, Delaney A, O'Neill F, Blakemore J, Bowen J, Husi H, Mitchell R, Grant SG, Fleetwood-Walker SM. Neuropathic sensitization of behavioral reflexes and spinal NMDA receptor/CaM kinase II interactions are disrupted in PSD-95 mutant mice. Curr Biol. 2003;13:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hains BC, Saab CY, Waxman SG. Changes in electrophysiological properties and sodium channel Nav1.3 expression in thalamic neurons after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2005;128:2359–2371. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hata Y, Takai Y. Roles of postsynaptic density-95/synapseassociated protein 90 and its interacting proteins in the organization of synapses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:461–472. doi: 10.1007/s000180050445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, Bellini M, Inuzuka H, Xu J, Xiong Y, Yang X, Castleberry AM, Hall RA. Proteomic analysis of beta1-adrenergic receptor interactions with PDZ scaffold proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2820–2827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houslay MD. Disrupting specific PDZ domain-mediated interactions for therapeutic benefit. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:483–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina I projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science. 2003;299:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1080659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji RR, Woolf CJ. Neuronal plasticity and signal transduction in nociceptive neurons: implications for the initiation and maintenance of pathological pain. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:1–10. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin SX, Zhuang ZY, Woolf CJ, Ji RR. mitogen-activated protein kinase is activated after a spinal nerve ligation in spinal cord microglia and dorsal root ganglion neurons and contributes to the generation of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4017–4022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04017.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koltzenburg M, Torebjork HE, Wahren LK. Nociceptor modulated central sensitization causes mechanical hyperalgesia in acute chemogenic and chronic neuropathic pain. Brain. 1994;117(Pt 3):579–591. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laird JM, Bennett GJ. An electrophysiological study of dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord of rats with an experimental peripheral neuropathy. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:2072–2085. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T, Saro D, Spaller MR. Thermodynamic profiling of conformationally constrained cyclic ligands for the PDZ domain. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1385–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Sandkuhler J. Characterization of long-term potentiation of Cfiber- evoked potentials in spinal dorsal horn of adult rat: essential role of NK1 and NK2 receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1973–1982. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migaud M, Charlesworth P, Dempster M, Webster LC, Watabe AM, Makhinson M, He Y, Ramsay MF, Morris RG, Morrison JH, O'Dell TJ, Grant SG. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 1998;396:433–439. doi: 10.1038/24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owolabi SA, Saab CY. Fractalkine and minocycline alter neuronal activity in the spinal cord dorsal horn. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4306–4310. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piserchio A, Salinas GD, Li T, Marshall J, Spaller MR, Mierke DF. Targeting specific PDZ domains of PSD-95; structural basis for enhanced affinity and enzymatic stability of a cyclic peptide. Chem Biol. 2004;11:469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polgar E, Watanabe M, Hartmann B, Grant SG, Todd AJ. Expression of AMPA receptor subunits at synapses in laminae I-III of the rodent spinal dorsal horn. Mol Pain. 2008;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothbard JB, Garlington S, Lin Q, Kirschberg T, Kreider E, McGrane PL, Wender PA, Khavari PA. Conjugation of arginine oligomers to cyclosporin A facilitates topical delivery and inhibition of inflammation. Nat Med. 2000;6:1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/81359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saab CY, Waxman SG. Potentiation of sural nerve Abeta action potential after neurogenic inflammation. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1773–1777. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000137076.18387.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandkuhler J. Understanding LTP in pain pathways. Mol Pain. 2007;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saro D, Li T, Rupasinghe C, Paredes A, Caspers N, Spaller MR. A thermodynamic ligand binding study of the third PDZ domain (PDZ3) from the mammalian neuronal protein PSD-95. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6340–6352. doi: 10.1021/bi062088k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner P, Higley MJ, Xu W, Czervionke BL, Malenka RC, Sabatini BL. Destabilization of the postsynaptic density by PSD-95 serine 73 phosphorylation inhibits spine growth and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;60:788–802. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svensson CI, Schafers M, Jones TL, Powell H, Sorkin LS. Spinal blockade of TNF blocks spinal nerve ligation-induced increases in spinal P-p38. Neurosci Lett. 2005;379:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao F, Su Q, Johns RA. Cell-permeable peptide Tat-PSD-95 PDZ2 inhibits chronic inflammatory pain behaviors in mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1776–1782. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao F, Tao YX, Gonzalez JA, Fang M, Mao P, Johns RA. Knockdown of PSD-95/SAP90 delays the development of neuropathic pain in rats. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3251–3255. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao F, Tao YX, Mao P, Johns RA. Role of postsynaptic density protein-95 in the maintenance of peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;117:731–739. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tao YX, Huang YZ, Mei L, Johns RA. Expression of PSD- 95/SAP90 is critical for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated thermal hyperalgesia in the spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2000;98:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao YX, Johns RA. PDZ domains at excitatory synapses: potential molecular targets for persistent pain treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:217–223. doi: 10.2174/157015906778019473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tao YX, Raja SN. Are synaptic MAGUK proteins involved in chronic pain? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN. Peripheral and central mechanisms of cutaneous hyperalgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:397–421. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90027-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuda M, Mizokoshi A, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Inoue K. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in spinal hyperactive microglia contributes to pain hypersensitivity following peripheral nerve injury. Glia. 2004;45:89–95. doi: 10.1002/glia.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: uncovering the relation between pain and plasticity. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:864–867. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264769.87038.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu JT, Xin WJ, Wei XH, Wu CY, Ge YX, Liu YL, Zang Y, Zhang T, Li YY, Liu XG. p38 activation in uninjured primary afferent neurons and in spinal microglia contributes to the development of neuropathic pain induced by selective motor fiber injury. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Wu J, Lei Y, Fang L, Willis WD. Protein phosphatase modulates the phosphorylation of spinal cord NMDA receptors in rats following intradermal injection of capsaicin. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;138:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang XC, Zhang YQ, Zhao ZQ. Involvement of nitric oxide in long-term potentiation of spinal nociceptive responses in rats. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1197–1201. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200508010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]