Abstract

A better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which early life stress (ELS) modifies brain development and adult behavior is necessary for diagnosing and treating psychopathology associated with exposure to ELS. For historical reasons most of the work in rodents has been done in rats and attempts to establish robust and reproducible paradigms in the mouse have proven to be challenging. Here we show that under normal rearing conditions, increased levels of postnatal maternal care are associated with a decrease in anxiety-like behavior in BALB/cByj offspring. Brief daily pup-dam separation (BDS) during the postnatal period was associated with increased postnatal maternal care but was surprisingly associated with increased anxiety-like behavior in adult offspring, providing the first example in which offspring receiving higher levels of postnatal maternal care are more anxious in adulthood. Plasma corticosterone levels were elevated in BDS pups even three hours after the pups were reunited with the dam, suggesting that this paradigm represents a form of early life stress. We also show that levels of total RNA and DNA in the hippocampus reach a peak at postnatal day 14 and that exposure to BDS seems to inhibit this developmental growth spurt. We propose that exposure to stress during the postnatal period overrides the ability of high levels of postnatal maternal care to program anxiety-like behavior by inhibiting the normal growth spurt that characterizes this period.

Keywords: maternal care, early life stress, handling, neurodevelopment, mice, anxiety, Hippocampus

Introduction

Parent-infant interactions play an important role in the emotional and cognitive development of the infant in a manner that shapes many behavioral, emotional, and physiological responses in adulthood (Kaffman and Meaney, 2007). Retrospective and prospective studies have shown that exposure to parental abuse or neglect early in life increases risk for developing psychopathologies such as anxiety disorders, depression and psychosis (Mullen et al., 1996; Kaufman and Charney, 2001; Bebbington et al., 2004; Gilbert et al., 2009). In many cases these conditions persist throughout life and are associated with chronic mental illness that is refractory to treatment (Bryer et al., 1987; Muenzenmaier et al., 1993; Nemeroff et al., 2003). The mechanisms by which erratic forms of parental care interfere with normal neurodevelopment and its relationship with adult psychopathology are poorly understood in humans. However, the observation that parental care plays a similarly important role in shaping a broad array of behaviors in rodents and nonhuman primates suggests that some of the molecular details underlying this process can be studied in animal models (Kaffman and Meaney, 2007).

Work in rats has shown that levels of maternal care during the first 2 weeks of life influences a host of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive outcomes in the offspring, many of which persist into adulthood (Hofer, 1994; Levine, 2001; Meaney, 2001). For example, levels of maternal care during the first weeks of life are normally distributed in the rat such that some individuals provide almost 3 times higher levels of tactile stimulation in the form of licking and grooming (LG) compared to others (Champagne et al., 2003). High and Low LG dams were defined as those that are at least 1SD above and below the population’s average. This paradigm establishes two non-overlapping forms of parental care early in life. Offspring exposed to high levels of LG during the first week of life show blunted hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA) activation in response to stressors, are less fearful, and perform better on hippocampal dependent learning tasks compared to offspring exposed to low levels of LG (Meaney, 2001). Moreover, conditions that artificially increase frequency of LG in dams, such as brief periods of separation (a manipulation known as handling) or the addition of corticosterone to the drinking water during the first postnatal weeks, are also associated with a long-term decrease in stress reactivity in the offspring that are similar to those seen in offspring raised by High LG dams (Lee and Williams, 1974; Liu et al., 1997; Casolini et al., 2007). In contrast, conditions that disrupt maternal care such as those associated with prolonged levels of maternal separation or administration of benzodiazepine to dams during the handling procedure increase stress reactivity and anxiety-like behavior in the offspring in a manner that is similar to that seen in offspring raised by low LG dams (D’Amato et al., 1998; Lippmann et al., 2007).

Frequency of LG during the first week of life programs HPA reactivity in adulthood by regulating DNA methylation of a promoter element that controls expression of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in the rat hippocampus (Weaver et al., 2004). The ability of postnatal maternal care to regulate DNA methylation in post-mitotic neurons and the stability of these modifications provided a molecular mechanism to explain how events early in life are able to shape brain function in adulthood [reviewed in (Szyf et al., 2005)]. However, several observations suggest that DNA methylation is likely to provide only one of many “molecular tricks” by which events early in life shape neurodevelopment and behavior later in life. First, recent work demonstrated that some DNA methylation sites appear to be highly dynamic and far less stable compared to those reported for the GR, indicating that not all DNA methylation sites are able to support long-term changes in transcriptional regulation (Miller et al., 2008; Novikova et al., 2008). Second, many other epigenetic processes such as RNA editing (Lalli et al., 2003; Qureshi and Mehler, 2009; Tan et al., 2009), DNA recombination (Habibi et al., 2009), and a host of other chromatin remodeling mechanisms (Lund and van Lohuizen, 2004; Payer and Lee, 2008) are capable of mediating long-lasting stable alteration in cell fate and function. Third, long-term programming of gene expression is not necessary in order for events early in life to modify brain function in adulthood. The organized stepwise progression of neurodevelopment allows changes that interfere with a specific step earlier in life to modify functional output later in life, with monocular deprivation being the best characterized example of this concept (Hensch and Fagiolini, 2005).

In order to expand the search for novel mechanisms by which ELS modifies neurodevelopment and adult behavior we developed several paradigms that allow us to examine this issue in the mouse. The availability of transgenic animals and commercial platforms for conducting unbiased genomic and proteomic screens make the mouse an attractive model organism to study this problem rigorously. However, the establishment of ELS paradigms that are associated with robust and reproducible behavioral outcome in the mouse has proven to be a challenging task (Priebe et al., 2005; Millstein and Holmes, 2007), explaining the paucity of studies that have used transgenic animals or genomic tools to study this problem [for a rare example see (Carola et al., 2007)]. We hypothesized that careful monitoring of postnatal maternal care, appropriate selection of genetic background, the identification of reliable developmental markers modified by ELS, and appropriate sample size were necessary to establish a robust ELS paradigm in the mouse.

Methods

Animals

BALB/cByj (Balbc) and C57BL/6j (C57) mice, 6–8 weeks old were purchased from Jackson. Animals were housed in 8 × 11 inch Plexiglas cages and kept on a standard 12:12 hour light dark cycle (lights on at 7:00AM), constant temperature and humidity (22 C° and 50%) with food provided ad libitum. All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Yale University and conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and the Use of Laboratory Animals. See supplemental material for more details.

Mating and Cross fostering

After a 2-week acclimation period, animals were mated by placing 2 females and 1 male from the same strain in a cage layered with corncob bedding. After 2 weeks of mating visibly pregnant dams were placed individually in maternity cage containing 900 cc of Corncob bedding (Harlan) with no nesting material. Births were monitored daily at 10:00AM and day of birth was considered PND=0. At birth, roughly 50cc of old bedding from the fostering dam’s cage were placed in the corner of a new cage containing 900cc of clean bedding. Litters were culled to 6–8 pups and placed together in the area where the old bedding was placed. In cases where a foster dam was used to raise the pups (i.e. BB litters), the dam added to the cage was not the biological dam of the offspring but one that gave birth on the same day. The biological dam was placed with her own pups in B-sham litters. No nesting material was provided during the entire postnatal period and the bedding was changed on PND14 and at weaning.

Scoring maternal behavior

Maternal behavior was evaluated during the first 7 postnatal days after birth (PND=0–7) and scored during 4 periods of 60 min each. Two observation periods were conducted during the light phase (12:00 and 18:00) and 2 observations during the dark phase (21:00 and 06:00) using red light to illuminate the room. During each 60-minute period the behavior of the dam was sampled for 10 seconds at 4-min intervals. The following behaviors were monitored: licking/grooming pups, arched-back nursing, passive nursing, self-grooming, nest building, and no contact with pups. See supplemental material for more details.

Brief daily maternal separation

At birth (PND=0), pups were culled to 6–8 pups per litter and were placed in a new cage as described for the B-sham litters above (i.e. both control and BDS dams raised their own biological offspring). Cages were randomly assigned to either brief daily separation (BDS) or control groups. The separation procedure occurred daily from PND1-21 and was done from 11:00–11:40AM. During the procedure the dam was removed from the home cage and placed in a holding cage covered with fresh corncob bedding, and provided with food and water. Pups were transferred individually into a new cage covered with clean corncob bedding and placed individually at different corners of an 8 × 11 inch standard cage. Cages were left undisturbed for 15 min at ambient temperature in the vivarium (i.e. 22C° +/−2C°) after which the pups were individually transferred to their home cage followed by the return of the dam. Cages in the control group were left undisturbed except for cage maintenance preformed on PND14. At PND 22 all pups were weighed and housed in groups of two littermates of the same sex per cage.

Open field

An animal was placed in the right-lower corner of a black 50 × 50 cm Plexiglas box and its locomotor activity was recorded using an EthoVision (Noldus Information Technology) tracking system for 10 min. Distance traveled and the amount of time the animals spent in the inner 15cm-area was calculated by the software at 5-minute bins. See supplemental material for more details.

Step down assay

Animals were placed on a small 96-well plate covered with a rubber sheath to provide good grip for the animals. Latency to step off the platform (all four legs) was recorded by an observer who was blind to the developmental history of the animal. See supplemental material for more details.

Stress induction and plasma collection

Corticosterone and T3 measurements

Corticosterone levels were measured using a 125I RIA kit (MP Biomedicals, Cat. No. 07-120102) and followed manufacturer instructions. Triiodothyronine levels (T3) were measured using Siemens diagnostics 125I RIA kit (#TKT31). For more details see supplementary information.

RNA harvesting

All tissue processing was done between 2:00–3:00PM. Animals were killed by rapid decapitation and the hippocampus was dissected under a 3X illuminated magnifying glass using RNAase free conditions. Dissected hippocampi were placed in an eppendorf tube and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use. RNA was harvested using RNAqueous kit (Ambion), treated with DNase (Qiagen), and was further purified using RNeasy kit (Qiagen). For more details see supplementary information.

DNA quantification

Total hippocampal DNA was estimated from the homogenized hippocampus tissue (see RNA harvesting procedure) using the high sensitivity DNA Qubit kit (Invitrogen).

Quantitative PCR (q-PCR)

500 ng of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using random primers (Invitrogen) and superscript III RT kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR) was then used to assess levels of GR, GR-C, rRNA, and TBP in the hippocampus. For more details see supplementary information.

Statistical analysis

Data were carefully screened for inaccuracies, outliers, normality, sphericity, and homogeneity of variance. The different tests used are specified in the text and figure legends. The SPSS 16 software was used for the analysis and p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

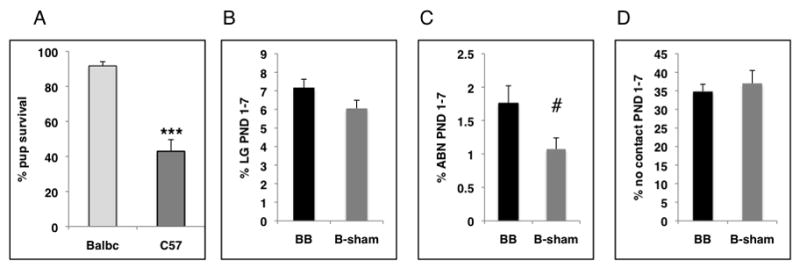

Here we show that the highly stressor-reactive BALB/cByj (Balbc) mouse strain possesses some important features that make it a particularly useful strain to study the effect of postnatal maternal care on neurodevelopment and adult behavior. First, we found that Balbc will readily take care of their pups even in the complete absence of nesting material allowing for accurate assessment of maternal care (note that an ample amount of corncob bedding material was present in the cage, see material and methods for details). This was not the case with the commonly used C57BL/6j (C57) strain in which nesting material was necessary to trigger maternal care and its absence was associated with a high rate of pup mortality (figure 1A, please note that with the exception of figure 1A all work presented here was conducted with Balbc animals only). Second, previous work has shown that Balbc offspring are sensitive to the neurodevelopmental effects of postnatal maternal care further justifying the use of this strain (Zaharia et al., 1996; Francis et al., 2003; Caldji et al., 2004; Carola et al., 2004). Third, whole-litter transfer did not alter maternal behavior in this strain indicating that Balbc dams raise their own biological offspring in a manner indistinguishable from that seen in dams raising a fostered litter (figure 1B–D). Since both prenatal and postnatal factors influence adult behavior (Francis et al., 2003), we used this cross-fostering strategy to randomize possible prenatal differences between high and low LG Balbc dams, allowing us to attribute differences in behavioral outcome between offspring of high and low LG dams to differences in postnatal maternal care.

Figure 1.

Maternal behavior is robust in Balbc dams. A. The absence of nesting material was associated with a significant decline in pup survival in C57BL/6j dams (n=33) but not in Balbc dams (n=24). B–D. At birth (PND 0) Balbc pups were culled to 6–8 and were either raised by their biological dam (B-sham, n=8) or a foster dam (BB, n=17). Maternal behavior was assessed from PND 1–7 and is shown as percent frequencies averaged over the first postpartum week. No differences in rates of LG (B), ABN (C), or time away from the pups (D) were seen between BB and B-sham. Means and SEM are shown, ***p<0.005, #p>0.1 (NS) unpaired student t-test. ABN-arched back nursing, NS-non significant.

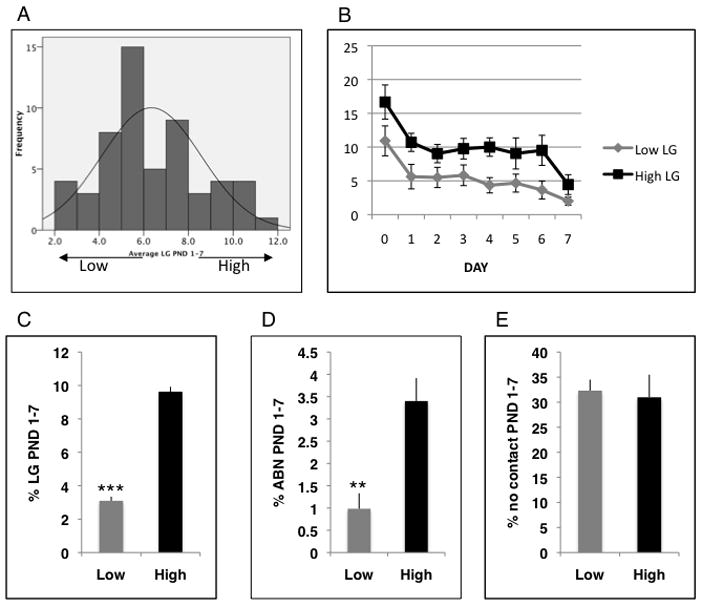

We characterized maternal behavior in a large cohort of Balbc dams raising fostered pups (BB, n=56) and showed that frequency of LG is normally distributed (figure 2A). We defined High (n=8) and Low LG (n=12) dams as those that were at least 1 SD above and below the mean. Rate of LG declined over the first week postpartum in both groups [main effect of days F(7,70)=5.25, p=.003, repeated measure ANOVA] with no differences in frequency of LG between High and Low LG dams at PND 7 (figure 2B). During the first postpartum week high LG dams spent significantly more time licking and grooming their pups [t(18)=15.90 p<0.0005] and engaging in an active form of nursing known as arched-back nursing [t(18)=3.48 p<0.003, figure 2B and 2C] compared to low LG dams. Similar to findings in the rat, we found a significant correlation between frequency of LG and frequency of arch-back nursing (ABN), although the magnitude of the correlation was more modest in Balbc (r=0.564, p<0.0005, n=56) compared to that previously reported in the rat (Liu et al., 1997). There were no differences in the total time the dams spent away from the pups or the total amount of passive nursing between the two groups (figure 2E). Finally there were no differences in percent survival or weight at weaning between offspring raised by High and Low LG dams (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Licking and grooming (LG) is normally distributed in a Balbc dam sample. A. Percent LG over the first postnatal week was calculated for a cohort of BB dams (n=56, Shapiro-Wilk test of normality=0.973, p= 0.246). B. Daily %LG for high LG (n=8) and low LG (n=12). There was a significant main effect of day, F(7,70)=5.24, p=0.003 as a within factor, and a main effect of group (High vs. Low) as a between factor, F(1,70)=396, p<0.0005. There were significant differences in percent LG (C), ABN (D), but not time spent away from pups (D) between high LG and low LG BB dams. Data are presented as means and S.E.M. **p< 0.01,***p< 0.005, unpaired student t-test. ABN-arched back nursing, BB-Balbc dams raising non-biological Balbc offspring.

We tested the effect of postnatal LG on anxiety-like behavior in a cohort of 22 adult male offspring raised by High or Low LG dams (levels of postnatal maternal care received by this group of offspring are shown in supplemental data figure S1). Only male offspring were included in the study because our preliminary studies and work from other laboratories suggested that behavioral sequelae of ELS in mice, especially those related to anxiety-like behavior, are more robust in male offspring (Denenberg et al., 1981; Berrebi et al., 1988; Parfitt et al., 2004; Kikusui et al., 2006; Millstein et al., 2006; Ren-Patterson et al., 2006). Here we show that male offspring of High LG dams spent significantly more time exploring the center area of an open field compared to offspring of Low LG dams (figure 3A). This difference was not simply due to a general increase in locomotor activity as there were no differences in total distances traveled between the groups once the animals were habituated to the arena (Figure 3C). Importantly, time in the center during the first 10 minutes exploring the open field was highly correlated with levels of LG these animals received during the first week of life (figure 3B, r=0.65, p=0.001), supporting the notion that levels of LG during a specific period of development program anxiety-like behavior in adulthood. In a second test of anxiety, offspring of High LG dams stepped off a small platform significantly faster compared to offspring of Low LG dams (figure 3D) in a manner that was negatively correlated with levels of postnatal LG (r=−0.543, p= 0.009). This anxiety-like assay measures the latency of the mouse to step off a platform, a behavior that occurs more readily following administration of benzodiazepines (Anisman et al., 2001). Work in the rat showed that frequency of LG is associated with long-term changes in stressor-induced HPA reactivity. However, we found no differences in corticosterone levels of High and Low LG offspring exposed to 15 minutes of swimming (figure 3E) and no differences in hippocampal GR mRNA levels between the two groups (data not shown).

Figure 3.

High frequency of LG during the first week of life is associated with decreased anxiety-like behavior in adult Balbc males. A. Low LG offspring (n=8) spent less time exploring the center of an open field in adulthood compared to offspring raised by high LG BB dams (n=14). B. Time exploring the open field in adulthood was correlated with frequency of LG during the first week of life (r= 0.65, p=0.001). C. Total distance travelled after 5 min of habituation to the open field. D. Offspring of high LG dams had shorter latencies to step off the platform in the step down assay compared to low LG offspring. E. Plasma corticosterone levels were assessed in offspring of high and low LG dams (n=6 from each group) immediately after exposure to 15 min of swimming in cold water (20C°). *p< 0.05, unpaired student t-test, means and SEM shown.

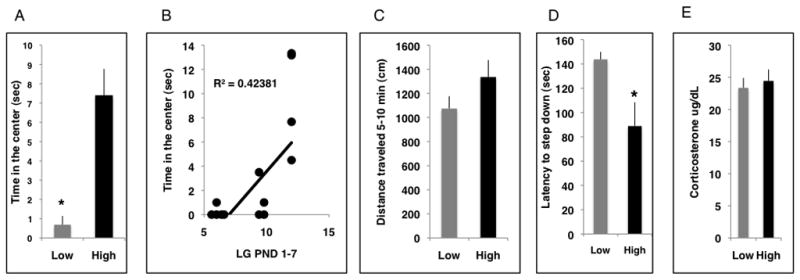

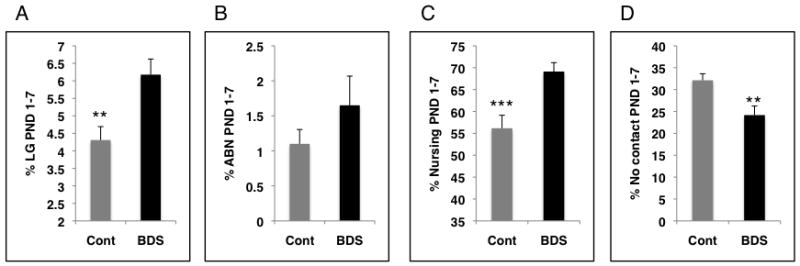

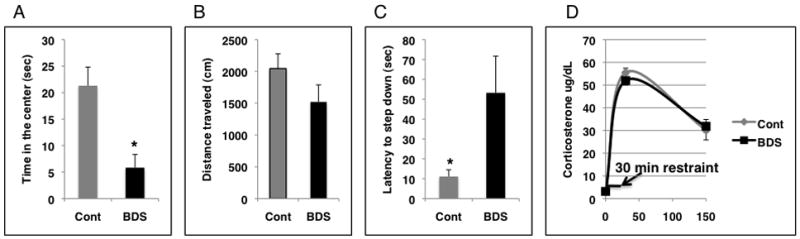

We attempted to confirm these results using an independent method in which we artificially increased levels of LG in Balbc dams by exposing them to brief daily periods of maternal separation (BDS), a manipulation known also as handling. Because of some unique features of our manipulation (see below) we chose the term BDS to describe it instead of handling. We first confirmed that BDS was associated with increased levels of LG. Indeed, BDS was associated with a robust increase in several forms of postnatal maternal care including LG, time nursing and time in contact with pups (figure 4). Moreover, this global increase in levels of postnatal care was detected soon after the pups were reunited with the dam (i.e. 12PM observations) and was still present 18 hours later during the 6AM observation the following day (supplemental data figure S2). Based on previous work in both rats and mice we predicted that mice exposed to BDS early in life would show decreased anxiety-like behavior compared to control offspring (Levine et al., 1957; Levine et al., 1967; Hess et al., 1969; Meaney et al., 1989; Meaney et al., 1992; D’Amato et al., 1998). Unexpectedly, adult offspring exposed to BDS spent less time in the center of the open field (figure 5A) and exhibited longer latencies in the step down assay (figure 5C) compared to control animals despite the fact that they received higher levels of maternal care early in life. We did not find differences in HPA reactivity (figure 5D) or GR mRNA levels in the hippocampus (supplemental data figure S3) between BDS and control offspring. We have now repeated this work using 3 independent cohorts (table 1); despite an increase in maternal care, BDS animals appeared more anxious in both the open field and the step down assays compared to controls.

Figure 4.

Brief daily separation (BDS) is associated with increased postnatal maternal care. Levels of maternal care in BDS (n=13 litters) and control (n=13 litters) groups were monitored for the first postnatal week and the average % frequencies and SEM observed during this period are summarized for LG (A), ABN (B), passively nursing pups(C), no contact with the pups (D). **p< 0.01,***p< 0.005, unpaired student t-test. ABN-arched back nursing, Cont-control, LG-licking and grooming.

Figure 5.

Adult offspring exposed to BDS show increased anxiety-like behavior compared to controls. A. Offspring exposed to BDS (n=8) during the first 3 weeks of life spent less time exploring the center of an open field compared to control (n=8). B. Total distance traveled in the open field after animals habituate to the field for 5 minutes (n=8 for each condition). C. Latency to step down from a slightly elevated platform was increased in offspring exposed to BDS (n=26) and control (n=23). D. BDS (n=12) and control (n=11) adult offspring were exposed to 20 min restraints and corticosterone plasma levels were tested at baseline (t=0) and 30 min and 150 min after the animals were placed in the restraining device. *p< 0.05, unpaired student t-test, means and SEM shown. BDS-brief daily separation, Cont-control condition.

Table 1.

Exposure to brief daily separation from PND 1–21 leads to a reproducible increase in anxiety-like behavior in adulthood. Three independent cohorts of Balbc animals were exposed to BDS or control conditions and their male offspring were tested in adulthood (PND60-90) in the open-field exploratory test and the step-down test.

| Independent verifications | Experimental group | Time (sec) exploring the center of an open field, Group mean (SEM) | Latency to step down in seconds, Group mean (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 | BDS (n=8) | 5.85 (2.5) | 28.9 (8.2) |

| Control (n=8) | 21.3 (3.5) | 12.5 (2.1) | |

| p value | 0.028 * | 0.04 * | |

| Cohort 2 | BDS (n=26) | 7.1 (2.0) | 53.2 (18.4) |

| Control (n=23) | 15.5 (2.5) | 11.1 (3.3) | |

| p value | 0.04 * | 0.017 * | |

| Cohort 3 | BDS (n=10) | 49.4 (4.4) | 35.7 (16.7) |

| Control (n=10) | 61.2 (4.4) | 152 (55.8) | |

| p value | 0.04 * | 0.04 * |

A summary of behavioral data is shown as means and (SEM),

p< 0.05 using unpaired student t test.

BDS-brief daily separation.

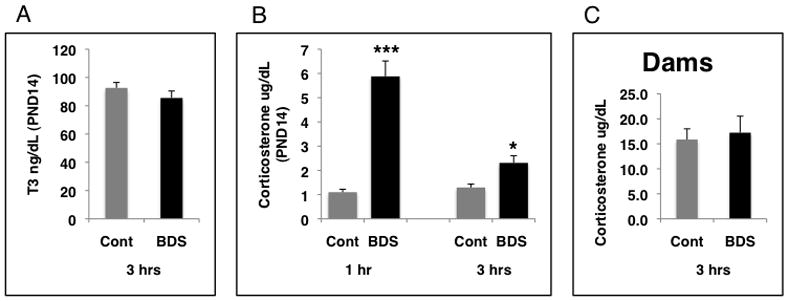

Brief removal of the pups from the safety of the nest activates physiological and behavioral responses in the pups that include release of thyroid hormones, increased levels of corticosterone, and increased vocalizations (Hofer, 1994; Levine, 2001). These changes are thought to be adaptive in that they protect the pups against hypothermia, hypoglycemia, and solicit maternal retrieval respectively. Since increased thyroid hormone levels have been shown to be necessary to increase GR levels in the developing hippocampus of handled rat pups (Meaney et al., 1987; Meaney et al., 2000), we assessed whether BDS was also associated with increased thyroid hormone levels during the postnatal period. Consistent with the absence of changes in GR levels in BDS mice, we found no differences in triiodothyronine (T3) levels between BDS and control postnatal day (PND) 14 pups (figure 6A). We then tested the effect of BDS on plasma corticosterone levels in PND 14 pups and found that corticosterone levels where roughly 5-fold higher 1 hour after pups were removed from their home cage (figure 6B). Note that at the 1-hour time point the pups were reunited with their dam and back in their home cage for about 40–45 minutes. Moreover, plasma corticosterone levels were still elevated even 3 hours after BDS pups were reunited with their dam (figure 6B). We assessed corticosterone levels in BDS and control dams 3 hours after separation to determine whether this prolonged elevation in pups’ corticosterone levels was perhaps due to higher corticosterone levels in BDS dams that was then transmitted to the pups in the breast milk. We found no differences in corticosterone levels between BDS and control dams suggesting that this increase in pups’ corticosterone levels was most likely due to endogenous HPA activation in the pups (figure 6C). This conclusion is consistent with the observation that BDS was not associated with prolonged elevation in corticosterone in PND 8 pups when the HPA system had not yet fully matured (data not shown). Exposure to BDS was not associated with changes in total body weight or percent pup survival when compared to the control group (data not shown).

Figure 6.

BDS is associated with prolonged elevation of corticosterone levels in PND14 pups. Pups were exposed to daily BDS for 14 days and sacrificed 3 hours after the last BDS exposure. Trunk blood was collected to assess plasma levels of triiodothyronine (T3) in PND14 BDS (n=6 pups from 6 different litters) and control (n=6 pups from 6 different litters). B. Pups were exposed to daily BDS and plasma corticosterone levels were assessed in PND14 pups at 1 hour and 3 hours after the last BDS exposure (BDS n= 6–8 pups for each time point, using different litters, control n= 6–9 pups for each time point using different litters). Note that at the 1-hour time point the pups were reunited with their dam and back in their home cage for roughly 40 minutes. C. Dams (BDS n=9 and control n=10) where exposed to BDS for 14 days and plasma corticosterone levels where assessed 3 hours after the last exposure to BDS. Unpaired student t-tests were used to compare BDS and control in A and C. One-way ANOVA was used to compare corticosterone levels in the 4 groups tested in panel B followed by Tukey-HSD post-hoc analysis (*p< 0.05, ***p< 0.0005 compared to control). Means and SEM shown. BDS-brief daily separation, Cont-control condition.

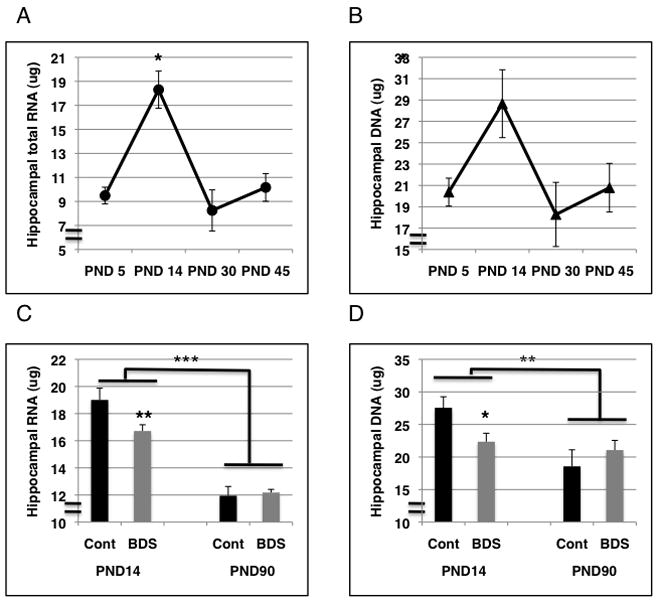

Since the hippocampus has previously been shown to be highly sensitive to the effect of ELS, we assessed the effect of ELS on hippocampal development. We first characterized normal hippocampal development by measuring levels of DNA and total RNA in PND5, 14, 30 and 45 of control animals. Levels of both RNA and DNA reach a peak at around PND14 and decline thereafter to reach adult levels (figure 7A&B). We then tested the effect of BDS exposure on levels of total RNA and DNA in PND14 and fully adult animals (PND90). Two way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of age on total RNA, F(1,24)=90.67, p<0.0005, and a significant interaction between age and developmental manipulation (i.e. BDS vs. control), F(1,24)=4.35, p=0.05. Simple effect analysis showed a significant difference in total RNA levels between BDS and control PND14 pups, F(1, 20)=7.09, p= 0.015, but not in PND90 offspring, F(1, 20)=0.07, p= 0.79 (figure 7C). Similarly, there was a significant main effect of age on total DNA, F(1,24)=8.00, p<0.01 and a significant interaction between age and developmental manipulation, F(1,24)=4.51, p=0.0046 due to decreased DNA content in PND14 exposed to BDS, F(1, 20)=4.3, p= 0.05, that was not present in PND90 offspring, F(1, 20)=1.1, p= 0.30, figure 7D. Levels of DNA and total RNA in the hippocampi were the same in BDS and control adult offspring, indicating that the effects of BDS on these crude measurements is restricted to a specific period of development and does not persist into adulthood (figure 7C&D).

Figure 7.

BDS alters hippocampal development. A. Hippocampi from PND5, 14, 30 and 45 of control animals (n=3–5 for each time point) were dissected and used to assess total hippocampal RNA and DNA across postnatal development. Levels of both RNA (A) and DNA (B) reach a peak during PND14, F(3, 18)=9.18, p= 0.001, one way ANOVA with Tukey HSD<0.05 used to compare levels in PND14 pups to other time points. Hippocampi from PND14 (BDS n=6, control n=6) and adult animals (PND=90, BDS n=6, control n=6) were used to assess levels of total RNA (C) and total DNA (D). Two-way ANOVA was used to assess main effects of age (PND14 vs. PND90) and developmental exposure (BDS vs. control) and their interaction. Simple effects for each age group were used to follow significant interaction. *p< 0.05 simple effect of BDS vs. control for PND14 pups, **p< 0.01 for main effect of age. BDS-brief daily separation, Cont-control condition.

Discussion

BDS is a reliable ELS model in Balbc mice

Exposure to ELS is associated with increased risk for several psychopathologies including anxiety, depression, and psychosis (Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Bebbington et al., 2004; Gilbert et al., 2009; Kaffman, 2009). The mechanisms by which ELS modifies neurodevelopment, brain functioning, and behavior in adulthood are poorly understood in humans. However, recent work in rats has demonstrated the potential of using cross-species studies to map some of the molecular details that govern this process (McGowan et al., 2009). For historical reasons most of the work on the effect of ELS on neurodevelopment and behavior in rodents used rats, with fewer examples described in the mouse. Yet, several molecular tools uniquely available in the mouse make it an attractive model organism to dissect the processes by which ELS modifies neurodevelopment and behavior. These include whole genome platforms to assess mRNA expression levels, genomic tools for unbiased mapping of epigenetic modifications, and the ability to generate transgenic animals. However, establishing this work in the mouse has proven to be challenging, limiting the utility of this molecular arsenal to study this issue in the mouse.

Given the importance of postnatal maternal care (especially frequency of LG) in programming adult behavior, we searched for a mouse strain that would allow us to accurately monitor postnatal maternal behavior. We found that Balbc dams show robust maternal behavior even in the absence of nesting material, allowing for accurate monitoring of maternal care in this strain. In addition, Balbc dams readily raise fostered pups in a manner indistinguishable from their maternal behavior towards their own biological offspring. Using the cross-fostering approach we showed that the frequency of postnatal LG is normally distributed in this strain and that as in the rat, offspring of high LG dams show decreased anxiety-like behavior compared to those of Low LG dams. We also showed that levels of LG during the first week of life are highly correlated with anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, consistent with the notion that tactile stimulation during early development modifies neurodevelopment of circuits that regulate anxiety-like behavior in adulthood. This work demonstrates the importance of carefully monitoring postnatal maternal behavior in order to establish developmental paradigms in the mouse that are associated with robust and reproducible behavioral outcomes in adulthood.

We attempted to replicate these findings by artificially elevating levels of postnatal maternal care using brief pup-dam daily separations. As predicted, BDS was associated with a robust increase in postnatal maternal care. However, contrary to expectations, BDS animals were more anxious in adulthood compared to control animals. The finding of elevated corticosterone levels and decreased DNA and RNA in PND14 pups provides important developmental markers that help ensure reproducibility across cohorts and laboratories. We repeated these studies several times, demonstrating that BDS is associated with robust and reliable neurodevelopmental and long-term behavioral consequences in Balbc mice (table 1). We are now using whole genome microarray studies and transgenic animals to better understand the cellular mechanisms by which BDS modifies neurodevelopment and adult behavior in this strain.

Revisiting the maternal mediation hypothesis of postnatal handling

According to the maternal mediation hypothesis (Liu et al., 1997), the ability of BDS (i.e. handling) to reduce anxiety-like behavior in adulthood is mediated by the ability of this manipulation to solicit additional maternal care during the postnatal period. Our finding that Balbc offspring exposed to BDS were more anxious despite their ability to recruit additional postnatal maternal care suggests that such induction may not be sufficient to alter behavior under some circumstances. We propose that anxiety-like behavior in adulthood is determined by the relative balance that BDS establishes between two opposing factors: induction of high levels of postnatal maternal care, especially frequency of LG, reduces anxiety-like behavior in adulthood whereas exposure to high levels of corticosterone during this period increases it in adulthood. This model is supported by the observation that offspring of high LG are less anxious compared to those of low LG dams (figure 3). In addition, previous work showed that under conditions where BDS induces only a brief elevation in corticosterone levels (i.e. corticosterone levels return to baseline within 30 min after the pups were reunited with the dam) the influence of elevated maternal care dominated the balance and the handled offspring appear less fearful in adulthood (D’Amato et al., 1998; Moles et al., 2008). Administration of benzodiazepine to the dams prior to reunification with the pups abolished the increase in postnatal maternal care and eliminated the ability of this manipulation to decrease anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, suggesting that induction of maternal behavior under conditions of limited exposure to stress is necessary to reduce anxiety-like behavior in handled animals (D’Amato et al., 1998). In contrast, experimental conditions that induce high and prolonged levels of stress, like those reported here, override the effects of maternal care resulting in increased anxiety-like behavior in the offspring. Indeed, exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids during the postnatal period decreased DNA levels in the hippocampus and decreased exploratory behavior in the open field assay (Howard, 1968; Howard and Granoff, 1968; Bohn, 1980), consistent with the notion that exposure to high levels of corticosterone is responsible for the developmental and behavioral sequelae of our handling paradigm. This hypothesis underscores the importance of monitoring both levels of maternal care and corticosterone levels during development in order to ensure reproducible outcomes. Moreover, this model predicts that under some experimental conditions these two opposing factors may cancel each other out, providing a possible explanation for the failure of previous attempts to detect changes in anxiety-like behavior in several mice strains exposed to BDS (Millstein and Holmes, 2007).

Several factors may account for the prolonged stress response seen in our procedure. First, during the 15-minute separation period pups were scattered in a cage that was covered with clean bedding and kept at room temperature (i.e. 22 C°). It is likely that the absence of maternal cues, the lack of contact with other pups and the hypothermia induced by this manipulation all contributed to the robust elevation in corticosterone levels we found. Second, the absence of nesting material and the presence of an observer assessing maternal care in the room may also have made the reuniting conditions less conducive for reducing stress in the pups. Third, levels of maternal care during the second and third week of exposure to BDS may not have been adequate to compensate for HPA activation during a period in which the HPA matures in these pups. Finally, previous work has shown that Balbc mice show high levels of stress reactivity compared to other strains (Shanks et al., 1990; Zaharia et al., 1996), raising the possibility that genetic makeup may make this strain particularly vulnerable to this manipulation. This possibility is of particular interest because it will allow us to study the mechanism by which genetic factors modify developmental sequelae of ELS, an important clinical issue that is currently poorly understood.

BDS inhibits a developmental growth spurt in the hippocampus

We characterized the effect of handling on hippocampal development and showed that under normal conditions the hippocampus undergoes a growth spurt that culminates at around PND14. This growth spurt is characterized by peak levels of total RNA and DNA that decline thereafter to reach their adult levels at around PND30 (figure 7). This wave-form is consistent with the well-documented pattern of an overproduction phase followed by a pruning phase that has been described for synaptogenesis and to a lesser degree for neurogenesis during this period (Bohn, 1980; Rakic et al., 1986; Katz and Shatz, 1996; Hua and Smith, 2004; Faulkner et al., 2007). One of the best-characterized examples of this process in the hippocampus has been the developmental maturation of the infrapyramidal bundle (IPB) of the mossy fibers. These axons connect the dentate gyrus with basal dendrites of CA3 pyramidal cells and undergo an extension phase during the first 3 weeks of postnatal life, after which these axons undergo a dramatic pruning that is completed at around PND 30 resulting in much shorter IPB length characteristic of adult animals [reviewed in (Faulkner et al., 2007)]. The functions that these developmental expansion and contraction processes play in adult brain function are not entirely clear. Nevertheless, it is thought that the expansion phase ensures the establishment of a long distance, highly distributive wiring system, whereas the trimming phase eliminates non-functional and redundant connections, thereby facilitating efficient and accurate information processing (Katz and Shatz, 1996; Hua and Smith, 2004). This notion is consistent with the observations that mice with longer IPB perform better on several hippocampal dependent tasks and that manipulations that increase IPB length are also associated with improved cognitive performance in these tasks (Faulkner et al., 2007).

Here we show that BDS appears to inhibit the expansion phase of the hippocampal growth spurt and propose that this inhibition would have long-term effects on hippocampal function in adulthood. It is also possible that exposure to BDS may simply shift this developmental curve to earlier or later phases of development, an issue that could be resolved by monitoring this process in more detail throughout the first 4 weeks of life. Levels of total RNA and DNA in the hippocampus are similar in BDS and control adult animals indicating that the effects of BDS on these markers is restricted to the postnatal period and is not extended into adulthood. These findings underscore the need to better characterize cellular processes that are modified by BDS during this developmental growth spurt and the contribution of these developmental changes to adult brain function. The availability of whole-genome microarray platforms to map developmental differences between control and BDS animals provide a promising strategy to identify novel cellular pathways that mediate the effects of ELS on brain development and adult behavior.

Conclusion

Here we show that brief daily separation of pups from their dam during the first three weeks of life is associated with a robust and reproducible increase in anxiety-like behavior in the offspring, despite the increased levels of postnatal maternal care the BDS offspring received during the postnatal period. This paradigm induces prolonged elevations of plasma corticosterone levels that are associated with alterations in normal hippocampal development at about two weeks of age. We propose that exposure to stress during the postnatal period overrides the ability of high levels of postnatal maternal care to program anxiety-like behavior by inhibiting the normal growth spurt that characterizes this period.

Supplementary Material

The average % frequencies and SEM of postnatal maternal care provided to the adult cohort used in the behavioral testing shown in figure 3 is summarized for LG (A), ABN (B), and no contact with the pups (C). #p= 0.07,***p< 0.0005, unpaired student t-test. ABN-arched back nursing, Cont-control, LG-licking and grooming.

BDS is associated with sustained increase in levels of postnatal maternal care. Levels of maternal care in BDS (n=13 litters) and control (n=13 litters) groups were monitored for the first postnatal week. The average % daily frequencies and SEM observed during the 12PM (noon) and 6AM observation periods are shown. Note that the 12PM observation took place 1 hr after exposure to BDS while the 6AM observation took place 18 hrs after exposure to BDS. A & D. Daily % LG show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (A), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=5.97 p= 0.022, and the 6AM observation (D), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=4.03 p= 0.056. B & E. Daily % no contact show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (B), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.58 p= 0.017, and the 6AM observation (E), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.07 p= 0.021. C & F Daily % nursing show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (C), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.50 p= 0.018, and the 6AM observation (F), repeated ANOVA F (1,24)=11.85 p= 0.002. ABN-arched back nursing, Cont-control, LG-licking and grooming.

BDS does not modify expression of GR mRNA levels in the hippocampus. Quantitative PCR was used to compare levels of total GR and GR-1C mRNA levels in adult offspring exposed to BDS (n=5) or control conditions (n=5). The 2ΔΔCT method was used to assess levels of GR-total and GR-1C levels in BDS animals with TBP as an internal control gene and the control group used as the calibrator. A ratio of 1 indicates no differences between BDS and control animals. BDS-brief daily separation, Cont-control condition, TBP-TATA binding protein.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Dr. Michael Meaney for helpful advice on establishing this work in the mouse. This work was funded by NIMH 1KO8MH074856, NARSAD young investigator awards 2004 and 2007, APIRE/Wyeth M.D.; Ph.D. Psychiatric Research Award 2005, and the APIRE/Merck Early Academic Career Research Award 2006.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anisman H, Hayley S, Kelly O, Borowski T, Merali Z. Psychogenic, neurogenic, and systemic stressor effects on plasma corticosterone and behavior: mouse strain-dependent outcomes. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:443–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, Singleton N, Farrell M, Jenkins R, Lewis G, Meltzer H. Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage: evidence from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:220–226. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi AS, Fitch RH, Ralphe DL, Denenberg JO, Friedrich VL, Jr, Denenberg VH. Corpus callosum: region-specific effects of sex, early experience and age. Brain Res. 1988;438:216–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MC. Granule cell genesis in the hippocampus of rats treated neonatally with hydrocortisone. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2003–2012. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryer JB, Nelson BA, Miller JB, Krol PA. Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1426–1430. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldji C, Diorio J, Anisman H, Meaney MJ. Maternal behavior regulates benzodiazepine/GABAA receptor subunit expression in brain regions associated with fear in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1344–1352. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carola V, D’Olimpio F, Brunamonti E, Bevilacqua A, Renzi P, Mangia F. Anxiety-related behaviour in C57BL/6 <--> BALB/c chimeric mice. Behav Brain Res. 2004;150:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carola V, Frazzetto G, Pascucci T, Audero E, Puglisi-Allegra S, Cabib S, Lesch KP, Gross C. Identifying Molecular Substrates in a Mouse Model of the Serotonin Transporter x Environment Risk Factor for Anxiety and Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolini P, Domenici MR, Cinque C, Alema GS, Chiodi V, Galluzzo M, Musumeci M, Mairesse J, Zuena AR, Matteucci P, Marano G, Maccari S, Nicoletti F, Catalani A. Maternal exposure to low levels of corticosterone during lactation protects the adult offspring against ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7041–7046. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1074-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Francis DD, Mar A, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato FR, Cabib S, Ventura R, Orsini C. Long-term effects of postnatal manipulation on emotionality are prevented by maternal anxiolytic treatment in mice. Dev Psychobiol. 1998;32:225–234. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199804)32:3<225::aid-dev6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH, Rosen GD, Hofmann M, Gall J, Stockler J, Yutzey DA. Neonatal postural asymmetry and sex differences in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;254:417–419. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RL, Low LK, Cheng HJ. Axon pruning in the developing vertebrate hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 2007;29:6–13. doi: 10.1159/000096207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD, Szegda K, Campbell G, Martin WD, Insel TR. Epigenetic sources of behavioral differences in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:445–446. doi: 10.1038/nn1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi L, Ebtekar M, Jameie SB. Immune and nervous systems share molecular and functional similarities: memory storage mechanism. Scand J Immunol. 2009;69:291–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, Fagiolini M. Excitatory-inhibitory balance and critical period plasticity in developing visual cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2005;147:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Denenberg VH, Zarrow MX, Pfeifer D. Modification of the corticosterone response curve as a function of handling in infancy. Physiol Behav. 1969;4:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA. Hidden regulators in attachment, separation, and loss. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:192–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard E. Reductions in size and total DNA of cerebrum and cerebellum in adult mice after corticosterone treatment in infancy. Exp Neurol. 1968;22:191–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard E, Granoff DM. Increased voluntary running and decreased motor coordination in mice after neonatal corticosterone implantation. Exp Neurol. 1968;22:661–673. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua JY, Smith SJ. Neural activity and the dynamics of central nervous system development. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nn1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A. The silent epidemic of neurodevelopmental injuries. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:624–626. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A, Meaney M. Neurodevelopmental Sequelae of Postnatal Maternal Care in Rodents: Clinical and Research Implications of Molecular Insights. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:224–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Charney D. Effects of early stress on brain structure and function: implications for understanding the relationship between child maltreatment and depression. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:451–471. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikusui T, Nakamura K, Kakuma Y, Mori Y. Early weaning augments neuroendocrine stress responses in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli E, Ohe K, Latorre E, Bianchi ME, Sassone-Corsi P. Sexy splicing: regulatory interplays governing sex determination from Drosophila to mammals. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:441–445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MHS, Williams DI. Changes in licking behavior in the rat mother following handling of young. Anim Behav. 1974:679–681. [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Primary social relationships influence the development of the hypothalamic--pituitary--adrenal axis in the rat. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Alpert M, Lewis GW. Infantile experience and the maturation of the pituitary adrenal axis. Science. 1957;126:1347. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3287.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Haltmeyer G, Karas G, Denenberg VH. Physiological and behavioral effects of infantile stimulation. Physiol Behav. 1967;2:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Bress A, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM, Monteggia LM. Long-term behavioural and molecular alterations associated with maternal separation in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3091–3098. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science. 1997;277:1659–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AH, van Lohuizen M. Epigenetics and cancer. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2315–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.1232504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Sapolsky RM. Thyroid hormones influence the development of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors in the rat: a mechanism for the effects of postnatal handling on the development of the adrenocortical stress response. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:278–283. doi: 10.1159/000124741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Sharma S, Viau V. Basal ACTH, corticosterone and corticosterone-binding globulin levels over the diurnal cycle, and age-related changes in hippocampal type I and type II corticosteroid receptor binding capacity in young and aged, handled and nonhandled rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;55:204–213. doi: 10.1159/000126116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Viau V, Sharma S, Sarrieau A. Neonatal handling alters adrenocortical negative feedback sensitivity and hippocampal type II glucocorticoid receptor binding in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;50:597–604. doi: 10.1159/000125287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Diorio J, Francis D, Weaver S, Yau J, Chapman K, Seckl JR. Postnatal handling increases the expression of cAMP-inducible transcription factors in the rat hippocampus: the effects of thyroid hormones and serotonin. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3926–3935. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03926.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Campbell SL, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation and histone acetylation work in concert to regulate memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein RA, Holmes A. Effects of repeated maternal separation on anxiety- and depression-related phenotypes in different mouse strains. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein RA, Ralph RJ, Yang RJ, Holmes A. Effects of repeated maternal separation on prepulse inhibition of startle across inbred mouse strains. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Sarli C, Bartolomucci A, D’Amato FR. Interaction with stressed mothers affects corticosterone levels in pups after reunion and impairs the response to dexamethasone in adult mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenzenmaier K, Meyer I, Struening E, Ferber J. Childhood abuse and neglect among women outpatients with chronic mental illness. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:666–670. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, Klein DN, Rush AJ, Schatzberg AF, Ninan PT, McCullough JP, Jr, Weiss PM, Dunner DL, Rothbaum BO, Kornstein S, Keitner G, Keller MB. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14293–14296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova SI, He F, Bai J, Cutrufello NJ, Lidow MS, Undieh AS. Maternal cocaine administration in mice alters DNA methylation and gene expression in hippocampal neurons of neonatal and prepubertal offspring. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt DB, Levin JK, Saltstein KP, Klayman AS, Greer LM, Helmreich DL. Differential early rearing environments can accentuate or attenuate the responses to stress in male C57BL/6 mice. Brain Res. 2004;1016:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer B, Lee JT. X chromosome dosage compensation: how mammals keep the balance. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:733–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe K, Romeo RD, Francis DD, Sisti HM, Mueller A, McEwen BS, Brake WG. Maternal influences on adult stress and anxiety-like behavior in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice: a cross-fostering study. Dev Psychobiol. 2005;47:398–407. doi: 10.1002/dev.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Regulation of non-coding RNA networks in the nervous system-What’s the REST of the story? Neurosci Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Bourgeois JP, Eckenhoff MF, Zecevic N, Goldman-Rakic PS. Concurrent overproduction of synapses in diverse regions of the primate cerebral cortex. Science. 1986;232:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.3952506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren-Patterson RF, Cochran LW, Holmes A, Lesch KP, Lu B, Murphy DL. Gender-dependent modulation of brain monoamines and anxiety-like behaviors in mice with genetic serotonin transporter and BDNF deficiencies. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:755–780. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9048-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks N, Griffiths J, Zalcman S, Zacharko RM, Anisman H. Mouse strain differences in plasma corticosterone following uncontrollable footshock. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;36:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90249-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M, Weaver IC, Champagne FA, Diorio J, Meaney MJ. Maternal programming of steroid receptor expression and phenotype through DNA methylation in the rat. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:139–162. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BZ, Huang H, Lam R, Soong TW. Dynamic regulation of RNA editing of ion channels and receptors in the mammalian nervous system. Mol Brain. 2009;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharia MD, Kulczycki J, Shanks N, Meaney MJ, Anisman H. The effects of early postnatal stimulation on Morris water-maze acquisition in adult mice: genetic and maternal factors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:227–239. doi: 10.1007/s002130050130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The average % frequencies and SEM of postnatal maternal care provided to the adult cohort used in the behavioral testing shown in figure 3 is summarized for LG (A), ABN (B), and no contact with the pups (C). #p= 0.07,***p< 0.0005, unpaired student t-test. ABN-arched back nursing, Cont-control, LG-licking and grooming.

BDS is associated with sustained increase in levels of postnatal maternal care. Levels of maternal care in BDS (n=13 litters) and control (n=13 litters) groups were monitored for the first postnatal week. The average % daily frequencies and SEM observed during the 12PM (noon) and 6AM observation periods are shown. Note that the 12PM observation took place 1 hr after exposure to BDS while the 6AM observation took place 18 hrs after exposure to BDS. A & D. Daily % LG show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (A), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=5.97 p= 0.022, and the 6AM observation (D), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=4.03 p= 0.056. B & E. Daily % no contact show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (B), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.58 p= 0.017, and the 6AM observation (E), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.07 p= 0.021. C & F Daily % nursing show significant main effect of BDS during the noon observation (C), repeated ANOVA F(1,24)=6.50 p= 0.018, and the 6AM observation (F), repeated ANOVA F (1,24)=11.85 p= 0.002. ABN-arched back nursing, Cont-control, LG-licking and grooming.

BDS does not modify expression of GR mRNA levels in the hippocampus. Quantitative PCR was used to compare levels of total GR and GR-1C mRNA levels in adult offspring exposed to BDS (n=5) or control conditions (n=5). The 2ΔΔCT method was used to assess levels of GR-total and GR-1C levels in BDS animals with TBP as an internal control gene and the control group used as the calibrator. A ratio of 1 indicates no differences between BDS and control animals. BDS-brief daily separation, Cont-control condition, TBP-TATA binding protein.