Abstract

Signals induced by the TCR and CD28 costimulatory pathway have been shown to lead to the inactivation of the constitutively active enzyme, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3), which has been implicated in the regulation of IL-2 and T cell proliferation. However, it is unknown whether GSK3 plays a similar role in naive and memory CD4+ T cell responses. Here we demonstrate a divergence in the dependency on the inactivation of GSK3 in the proliferative responses of human naive and memory CD4+ T cells. We find that although CD28 costimulation increases the frequency of phospho-GSK3 inactivation in TCR-stimulated naive and memory CD4+ T cells, memory cells are less reliant on GSK3 inactivation for their proliferative responses. Rather we find that GSK3β plays a previously unrecognized role in the selective regulation of the IL-10 recall response by human memory CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, GSK3β-inactivated memory CD4+ T cells acquired the capacity to suppress the bystander proliferation of CD4+ T cells in an IL-10-dependent, cell contact-independent manner. Our findings reveal a dichotomy present in the function of GSK3 in distinct human CD4+ T cell populations.

Costimulation, in the form of either soluble mediators or cell ligand-to-receptor interactions has been shown to potently augment the responsiveness of TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells (1). Initial work on costimulation led to the discovery of the B7/CD28 pathway, and ultimately to the confirmatory studies performed in CD28- and B7-deficient mice which altogether have underscored the importance of this pathway in adaptive immune responses (1). Subsequent work regarding the CD28 costimulatory pathway identified striking differences between naive and memory CD4+ T cells with respect to their dependency on CD28 costimulation for proliferative responses (2). In this regard, naive CD4+ T cell proliferation has been shown to be dependent on CD28 costimulation, whereas memory cell proliferation is less dependent on CD28 costimulation and can occur in its absence (2). Signaling differences between naive and memory CD4+ T cells have been reported (3, 4); however, the biochemical reasons for this differential requirement for CD28 remain ill defined. However, several laboratories have reported that the CD28 signaling pathway can still influence memory CD4+ T cell function (5, 6), thus raising the question of whether CD28 triggers distinct signaling pathways in memory CD4+ T cells and whether these signaling complexes play similar or distinct roles in naive and memory CD4+ T cells.

Although the downstream signaling pathways induced by CD28 are incompletely understood, CD28 costimulation has been shown to increase PI3K activity of which leads to the inactivation of the constitutively active serine/threonine kinase, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3)3 (7–12). Pharmacological inactivation of GSK3 in human T cells has been shown to mimic the CD28 costimulatory signal for T cell proliferation (9, 10). Although it is unclear exactly how GSK3 controls T cell proliferation, retrovirus-mediated expression of a constitutively active GSK3 βmutant in murine TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells also results in decreased proliferation with a concurrent suppression in IL-2 production upon TCR stimulation (13). In addition, both CD28 costimulation and pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 have been reported to promote the degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 in human CD4+ T cells, an event favoring the G1-S phase transition of TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells (9). Altogether, these findings suggest GSK3 is a prominent target of CD28 signaling which influences p27kip1 stability, IL-2 production, and T cell proliferation.

Because naive and memory CD4+ T cells differ with regard to their dependence on CD28 costimulation for proliferation and because GSK3 inactivation can compensate for certain phenotypic properties associated with CD28 costimulation, we investigated the regulation and dependency on GSK3 inactivation in human naive and memory CD4+ T cell-proliferative and effector cytokine responses. We report that although CD28 signaling amplifies the cellular levels of inactivated GSK3 in both naive and memory CD4+ T cell populations, memory cells are less reliant on GSK3 inactivation for their proliferative responses. Rather, we find that GSK3 activity plays an additional role in memory CD4+ T cells by regulating their IL-10 recall response.

Materials and Methods

Media

Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μM 2-ME, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 20 mM HEPES, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin.

Reagents

Anti-CD3/CD28-coupled microbeads and CFSE were purchased from Invitrogen. Anti-IL-10 (JES3-9D7), anti-CD4, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO, rat IgG1, rat IgG2a, anti-CD3 (OKT3), anti-CD28 (CD28.2), 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), and IL-10 ELISPOT kits and IL-4, IL-5, IL-17A, IFN-γ, IL-10, and TGF-β ELISA kits were obtained from eBioscience. Anti-IL-10R1 was purchased from BD Pharmingen. SB216763, LiCl, and wortmannin were purchased from Tocris, Calbiochem, and LC Laboratories, respectively. Nontargeting pools of small interfering RNA (siRNA) and a mixture of four prevalidated siRNA duplexes specific for GSK3α and GSK3β (ON TARGET-plus) were purchased from Dharmacon. TaqMan probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Western blot Abs and flow cytometric grade anti-phospho-GSK3α/β (S21/9) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies.

Isolation of PBMCs and T cells

PBMCs were obtained from the venous blood of normal adult donors after isolation of the leukocyte layer and elimination of RBCs using a Ficoll density gradient (University of Louisville (Louisville, KY), Institutional Review Board, Human Subjects Protection Program, study 503.05). Naive, memory, and unfractionated CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs by negative selection using kits from Miltenyi Biotech (>97.5% purity).

T cell stimulations

T cells (1 × 105 cells) were pretreated for 2 h with media containing DMSO (0.1%), wortmannin, NaCl, LiCl, or SB216763 at the indicated final concentration and transferred to plates preincubated with PBS, anti-CD3, or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml). Precoated anti-CD3/CD28 plates were prepared by incubating the tissue culture plate overnight at 4°C with PBS containing the indicated concentration of anti-CD3/CD28 Abs.

Flow cytometric analysis of phospho-GSK3

Purified CD4+ T cells were surface stained with anti-human CD4 and anti-human CD45RA for 10 min at room temperature and washed twice with medium. Cells were then counted and plated at 2.5 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well flat bottom plate and pretreated with DMSO (0.1%) or wortmannin (100 nM) for 30 min and then transferred to plates precoated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and CD28 (10 μg/ml). At the indicated time point, cells were transferred to 5-ml polystyrene round-bottom tubes and fixed by adding formaldehyde to a final concentration of 4% directly into the medium for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed once in PBS, resuspended in 90% methanol, and incubated on ice for 10 min. Cells were washed in PBS containing 2% FCS, then resuspended in PBS containing 2% FCS and anti-phospho-GSK3 (S9/21) Ab, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were washed twice in PBS containing 2% FCS and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry.

Cellular expansion and survival assays

Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated with 6 μM SB216763 or DMSO (0.01%) before stimulation for 2 h. Cells were then transferred to 96-well flat-bottom plates coated with PBS or anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml). On the indicated day, each group containing triplicate samples was counted individually using a hemocytometer. Cells were then treated with 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometric analysis. CFSE labeling was performed by adding 1 μM CFSE to memory CD4+ T cells at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml in PBS. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 8 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding FCS to a final concentration of 10%. Cells were additionally washed twice in PBS containing 2% FCS. The mean cycle number of the population of cells undergoing at least one cellular division was calculated using the formula log2 (G1) − log2 (G > 1) where G1 represents the geometric mean of the first generation and G > 1 represents the geometric mean of the subsequent generations.

Cytokine assays

Cell-free supernatants were analyzed for IL-2, IL-5, IL-10, IL-17A, IFN-γ, and TGF-β by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (eBioscience). IL-10 cytokine-secreting cells measured by ELISPOT were performed as directed by the manufacturer with the addition that the anti-CD3 Ab was added with the capture Ab. ELISPOTs were developed on day 4 postculture and analyzed by Cellular Technology.

Transfections and immunoblots

Memory CD4+ T cells were transfected using the Amaxa Nucleofection apparatus and the Amaxa Nucleofector kit for unstimulated T cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, siRNA-treated memory CD4+ T cells (5 × 106/100 μl) were mixed with 1 μg of the indicated siRNA. Samples were then transferred to cuvets and transfected using program V-24. Cells were rested in medium in the absence of any stimulus; on day 3, cells were washed, counted, and resuspended in fresh medium and stimulated with medium or plate-bound anti-CD3. Viability among the transfected groups was monitored by flow cytometry using 7-AAD and annexin V. GSK3α and GSK3β total protein levels were assessed on day 3 cells by Western blot. Whole-cell lysates were prepared as previously described (14). Twenty micrograms of total cellular protein from each group was suspended in lithium dodecyl sulfate buffer, heated for 10 min at 70°C, resolved by lithium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE, and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using the Novex system (Invitrogen). Probing and visualization of immunoreactive bands were performed using the ECL Plus kit (Amersham Pharmacia) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were acquired using the Kodak Image Station 4000MM system (Eastman Kodak).

Real-time PCR

RNA extraction and first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the 5 Prime PerfectPure RNA Cultured Cell Kit and High-Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 system. GAPDH mRNA levels were determined for each time point and were used as the endogenous control. Fold increase was calculated according to the 2-(δδCt) method (15).

Suppression assays

Day 4 cell-free supernatants from nonstimulated and stimulated memory CD4+ T cells (10 μg/ml immobilized anti-CD3 and DMSO (0.1%) or 6 μM SB216763) were transferred to freshly isolated CD4+ T cells and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 microbeads (bead-to-cell ratio, 1:5). Proliferation was assessed on day 4 by BrdU incorporation during the last 20 h of culture using the colorimetric BrdU assay (Calbiochem). OD values represent the difference of the mean of the experimental groups and the mean of BrdU-labeled nonstimulated cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between groups was evaluated by ANOVA and the Tukey multiple comparison test using the Instat program. Differences between groups were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

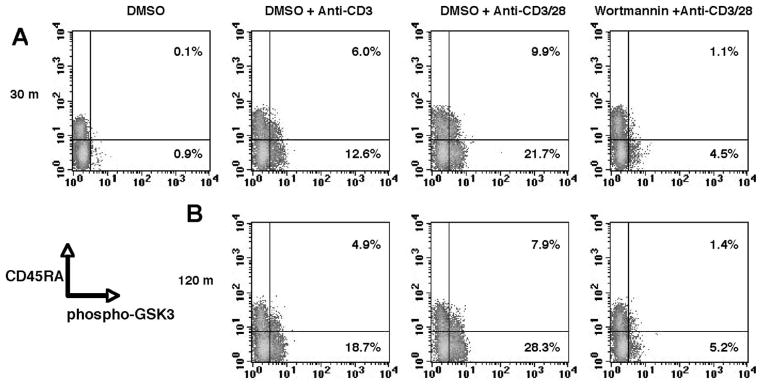

CD28 costimulation increases the frequency of phosphorylation-dependent GSK3 inactivation in naive and memory CD4+ T cells

CD28 costimulation has been shown to increase the cellular levels of inactivated GSK3 in TCR-activated human CD4+ T cells (9, 10). This process is dependent on the activation of the PI3K pathway by CD28 which leads to the phosphorylation of GSK3 (α/β) on S21 or S9 (respectively), and repression of GSK3 activity (10, 16). However, previous studies investigating GSK3 function in human T cells utilized unfractionated T cells or unfractionated CD4+ T cells (9, 10). Thus, we initially investigated whether human naive and memory CD4+ T cells display differences with regard to the ability of CD28 to promote the phosphorylation of GSK3 (S9/21) in the presence of TCR stimulation.

Although no perfect marker(s) exists to absolutely identify human naive and memory CD4+ T cell subsets, we nonetheless utilized CD45RA which is routinely used for discriminating naive and memory T cells (17–19). Multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of autologous naive (CD45RA+) and memory (CD45RA−) CD4+ T cells revealed that TCR stimulation increases the frequency of cells containing phospho-GSK3 in both subsets (Fig. 1). The presence of CD28 costimulation further augmented the frequency of naive and memory CD4+ T cells containing phospho-GSK3. Pretreatment of CD4+ T cells with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, abrogated the ability of anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation to induce the phosphorylation of GSK3, indicating that both naïve and memory CD4+ T cells utilize a similar pathway for the inactivation of GSK3 under these stimulation conditions (Fig. 1). These findings are consistent with previous observations demonstrating that PI3K activity is required for the phosphorylation of GSK3 upon CD28 costimulation in T cells (10). Thus, CD28 costimulation enhances the frequency of cells displaying phosphorylated GSK3 in TCR-stimulated naive and memory CD4+ T cells.

FIGURE 1.

TCR and CD28 co-stimulatory signals increase the frequency of naive and memory CD4+ T cells displaying phosphorylation-dependent GSK3 inactivation. Purified CD4+ T cells were pretreated for 2 h with a PI3K inhibitor (wortmannin; 100 nM) or DMSO (0.1%) alone and stimulated for 30 (A) or 120 (B) min with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml). Representative dot plots demonstrate the induction of the PI3K-dependent phosphorylation of GSK3 on S9/21 in CD45RA+ and CD45RA− populations. Results are representative of at least three individual experiments.

Human naive and memory CD4+ T cell proliferative responses vastly differ on their reliance for GSK3 inactivation

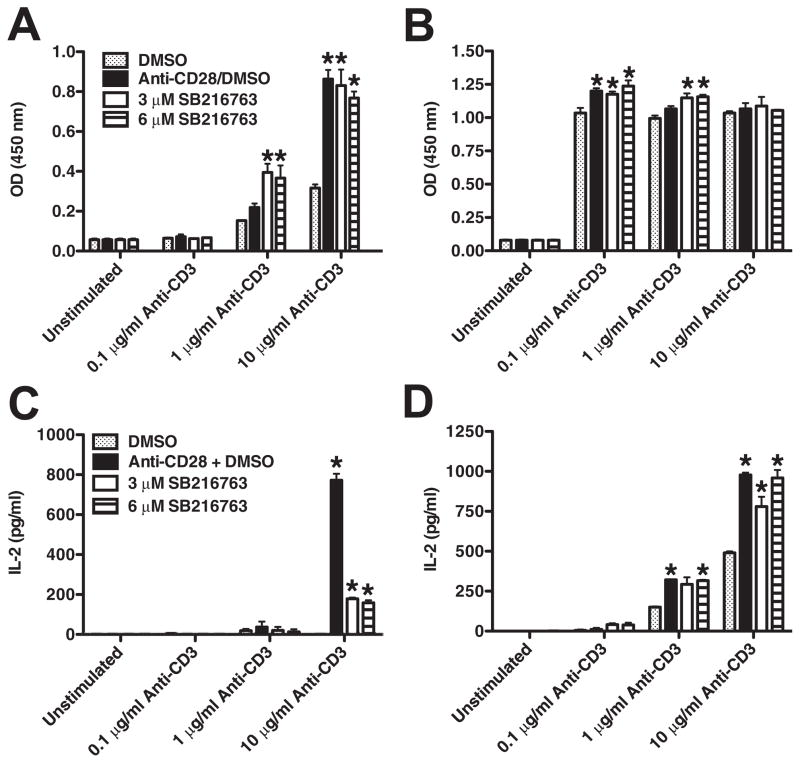

Previous work performed with unfractionated human CD4+ T cells and murine transgenic CD8+ T cells implicated GSK3 as a negative regulator of proliferation as the inactivation of GSK3 augmented the proliferative responses of TCR-stimulated cells (9, 10, 13). Because CD28 costimulation enhanced the S9/21-mediated inactivation of GSK3 in both naive and memory CD4+ T cell subsets, we next investigated whether human naive and memory CD4+ T cell proliferation was similarly dependent on GSK3 inactivation. CD28 costimulation increased the proliferative response of naive CD4+ T cells as compared with cells stimulated solely with anti-CD3. Inhibition of GSK3 using the GSK3-specific inhibitor, SB216763 (20) exhibited effects similar to those of the CD28 costimulatory signal, given that naive CD4+ T cells pre-treated with SB216763 also exhibited enhanced proliferative responses in response to stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the ability of GSK3 inactivation and CD28 costimulation to augment memory CD4+ T cell proliferation was dependent on the strength of the TCR signal (Fig. 2B). At low TCR signal strengths (0.1 μg/ml), memory CD4+ T proliferation was augmented upon GSK3 inactivation or CD28 costimulation, however, these increases were consistently less than that observed with naive cells (Fig. 2B). However, under stronger TCR signals (10 μg/ml; anti-CD3), memory CD4+ T cell proliferation was not significantly different upon GSK3 inactivation or CD28 costimulation despite the ability of CD28 costimulation to enhance the levels of phospho-GSK3 at this concentration of anti-CD3 (Fig. 1). The observed differences in the sensitivity of TCR-induced proliferation required for naive and memory CD4+ T cells are in line with the previous published work demonstrating memory CD4+ T cells respond to lower levels of TCR stimulation (21).

FIGURE 2.

Dependency of naive and memory CD4+ T cells on repression of GSK3 activity for proliferation and IL-2 production. Autologous naive or memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated for 2 h with DMSO (0.1%) alone or with the indicated concentration of SB216763 and then transferred to plates precoated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) or in conjunction with anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml). Proliferation of naive (A) and memory (B) CD4+ T cells was assessed by measuring the amount of BrdU incorporated during the last 20 h of a 4-day culture. IL-2 production of naive (C) and memory (D) CD4+ T cells was assessed from supernatants by ELISA 24 h postactivation. Results are representative of at least three individual experiments. *, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

Because we observed vast differences regarding the reliance on GSK3 repression for naive and memory CD4+ T cell-proliferative responses and because GSK3 has been previously shown to regulate the production of IL-2 by murine T cells (13), we next examined whether these differences were due to a differential ability of GSK3 to regulate IL-2 production in human naive and memory CD4+ T cells. No detectable level of IL-2 was observed in naive CD4+ T ells upon anti-CD3 stimulation at any concentration tested (Fig. 2C). However, upon CD28 costimulation or inhibition of GSK3, naive CD4+ T cell-derived IL-2 was detected (Fig. 2C). In contrast, IL-2 production by memory CD4+ T cells activated with TCR signals alone was detected and was significantly enhanced by either CD28 costimulation or GSK3 inhibition (at 1 and 10 μg/ml anti-CD3; Fig. 2D). Memory CD4+ T cell proliferation under weak TCR signals (0.1 μg/ml anti-CD3) occurred in the absence of detectable levels of IL-2, suggesting that memory CD4+ T cell proliferation is likely less dependent on IL-2 than their naive CD4+ T cell counterparts in which the detection of IL-2 correlated with proliferative responses (Fig. 2, B and D). Similar results were obtained using LiCl, which also inhibits GSK3 albeit by a different mechanism as compared with SB216763 (data not shown). Thus, despite the decreased dependence on GSK3 inactivation for memory CD4+ T cell proliferation, the production of IL-2 by memory CD4+ T cells remains strongly dependent on GSK3 inactivation.

We further examined naive and memory CD4+ T cell proliferative requirements by CFSE dilution analysis which allows for a more detailed examination of proliferation at the single-cell level. For these experiments, we used anti-CD3 at 10 μg/ml, because this concentration was used in Fig. 1 and induced detectable levels of naive CD4+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 2A). However, for these studies the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 was replaced with the GSK3 inhibitor LiCl, because SB216763-treated cells exhibited fluorescent properties partially overlapping the fluorescent spectra emitted by CFSE-treated cells. Pretreatment of naive CD4+ T cells with LiCl significantly increased the frequency of cells undergoing at least one cellular division as compared with NaCl-pretreated cells (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, naive cells treated with LiCl also displayed a higher mean cycle number for those cells displaying at least one cellular division than did NaCl-treated cells (Fig. 3C). Similar enhancement in naive CD4+ T cell proliferation was observed upon CD28 costimulation (data not shown). In contrast, no significant difference in the frequency of cells undergoing at least one cellular division or in the mean cycle was observed in memory CD4+ T cells stimulated in the presence of LiCl or CD28 costimulation (data not shown) as compared with control cells (Fig. 3, A–C). These differences in proliferation between naive and memory CD4+ T cells upon GSK3 inhibition correlated with the degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 as the pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 decreased the cellular levels of p27kip1 in naive, but not memory CD4+ T cells upon TCR cross-linking (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that naive and memory CD4+ T cells differ considerably in their dependence on GSK3 inactivation for proliferation.

FIGURE 3.

GSK3 inactivation differentially influences naive and memory CD4+ T cell proliferation and p27kip1 degradation. A, Autologous CFSE-labeled naive or memory CD4+ T cells pretreated with NaCl (6 mM) or LiCl (6 mM) were stimulated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and analyzed on day 4 by flow cytometry. B, Percentage of cells undergoing at least one cellular division from cells stimulated as above. C, Mean cycle number of cells undergoing at least one cellular division and stimulated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) in the presence of NaCl (6 mM) or LiCl (6 mM). D, Western blot analysis of p27kip1 levels from lysates derived from autologous naive or memory CD4+ T cells pretreated with DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 (SB; 6 μM) and stimulated for 48 or 72 h. Results are representative of at least three individual experiments. *, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

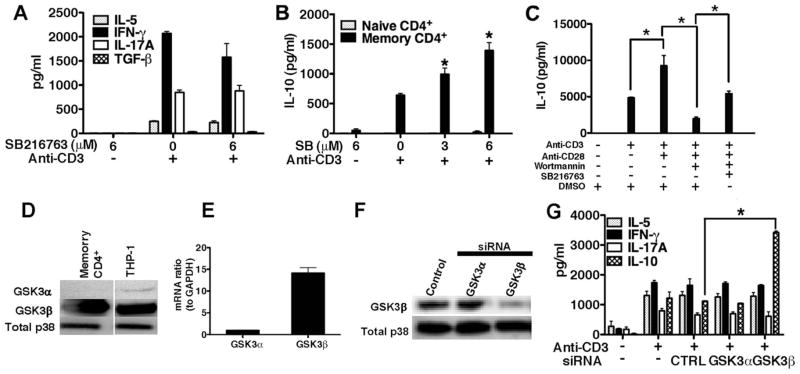

GSK3β selectively regulates the IL-10 recall response of memory CD4+ T cells

Because the pharmacological inactivation of GSK3 at strong TCR signals did not significantly influence the proliferation of memory CD4+ T cells, we next investigated whether GSK3 activity influenced the production of effector cytokines by memory CD4+ T cells. No significant effect was observed with respect to the production of the effector cytokines IL-5, IFN-γ, IL-17A, or TGF-β upon GSK3 inactivation (Fig. 4A). However, significant increases in IL-10 production were observed upon GSK3 inactivation by memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4B). GSK3 inactivation did not lead to increased IL-10 production by naive CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained upon flow cytometric sorting of memory CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

GSK3β is the predominant isoform of GSK3 in human memory CD4+ T cells and suppresses their production of IL-10. A, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated for 2 h with DMSO (0.1%) or with the indicated concentration of SB216763 (SB) and then transferred to plates precoated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml), and supernatants were analyzed by ELISA on day 4. B, Autologous naive or memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated for 2 h with DMSO (0.1%) alone or with the indicated concentration of SB216763 and then transferred to plates precoated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and analyzed for IL-10 levels by ELISA on day 4. C, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated with DMSO (0.1%), wortmannin (100 nM), or wortmannin and SB216763 (6 μM) and then stimulated for 4 days with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) alone or in conjunction with anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml). On day 4, cell-free supernatants were analyzed for IL-10 by ELISA. D, Cell lysates were prepared from purified memory CD4+ T cells and the THP-1 cell line (positive control). Blots were initially probed for GSK3α, stripped, and reprobed for GSK3β or total p38 (loading control). E, Relative levels of GSK3α and GSK3β mRNA to GAPDH in resting human memory CD4+ T cells. F, Memory CD4+ T cells were mock transfected or transfected with GSK3α- or GSK3β-specific siRNA. Cellular lysates were prepared on day 3 and analyzed by Western blot. G, Memory CD4+ T cells were mock transfected or transfected with equal amounts of nontargeting siRNA control (CTRL), GSK3α-specific siRNA, or GSK3β-specific siRNA. On day 3, transfected cells were transferred to anti-CD3 coated plates (1 μg/ml) and supernatants were analyzed for IL-5, IL-10, IL-17A, and IFN-γlevels by ELISA four days later. Results are mean values ± SEM of triplicate cultures and representative of three individual experiments.*, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

Because CD28 costimulation further repressed GSK3 activity in a PI3K-dependent manner (Fig. 1) coupled with the finding that the direct inactivation of GSK3 in the absence of CD28 costimulation augmented IL-10 production upon TCR cross-linking (Fig. 4B), we next investigated whether CD28 costimulation of memory CD4+ T cells could also promote IL-10 production and whether this attribute required PI3K activity. CD28 costimulation of TCR-stimulated memory CD4+ T cells significantly increased IL-10 levels as compared with anti-CD3 stimulation alone (Fig. 4C). Inhibition of the PI3K pathway led to significant reductions in the levels of IL-10 upon CD3/CD28 stimulation, demonstrating that PI3K activity was required for the induction of IL-10 upon CD3/CD28 stimulation (Fig. 4C). The inactivation of GSK3 using the GSK3-specific inhibitor SB216763 in CD3/CD28-stimulated memory CD4+ T cells partially rescued the deficiencies in IL-10 production observed upon PI3K inhibition (Fig. 4C). Thus, these findings suggest that GSK3 is responsible for the ability of the PI3K pathway to regulate IL-10 production by CD3/CD28-stimulated human memory CD4+ T cells.

Because GSK3 can exist as two major isoforms encoded by separate genes (16), GSK3α and GSK3β, we next investigated which isoform was suppressing IL-10 production. GSK3β, but not GSK3α, was detected in whole-cell lysates derived from memory CD4+ T cells by Western blot (Fig. 4D). Moreover, only phospho-GSK3β (S9) was observed in memory cells by Western blot analysis (data not shown). mRNA analysis of resting memory CD4+ T cells confirmed the predominance of the GSK3β isoform (Fig. 4E). We next used siRNA-mediated gene silencing to confirm the functional role of the GSK3β isoform in selectively suppressing IL-10 production from memory CD4+ T cells. The specificity of GSK3β siRNA pools was confirmed by Western blot given that cells transfected with GSK3β -, but not GSK3α-specific siRNAs, exhibited reduced levels of GSK3β protein as compared with mock-transfected cells (Fig. 4F). Knockdown of GSK3β protein using pools of siRNA significantly increased IL-10 production, but not of the other cytokines examined by human memory CD4+ T cells upon TCR activation, as compared with cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 4G). In contrast, cells transfected with pools of GSK3α siRNA did not produce significantly different amounts of IL-10 as compared with cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 4G). These data demonstrate that the GSK3β isoform selectively suppresses IL-10 production by human memory CD4+ T cells.

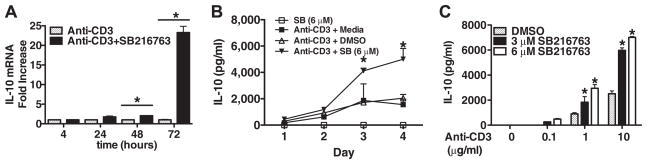

GSK3 regulates the magnitude of IL-10 production by memory CD4+ T cells

We next assessed whether GSK3 activity influences the steady-state levels of IL-10 mRNA in memory CD4+ T cells. No differences were found in the levels of IL-10 mRNA between GSK3-inactivated and control cells at either 4 or 24 h postactivation (Fig. 5A). However, by 48 h, significantly higher levels of IL-10 mRNA were observed in GSK3-inactivated cells than in cells stimulated in the presence of DMSO. By 72 h, GSK3-inactivated cells contained 23-fold higher levels of IL-10 mRNA than did cells stimulated in the presence of DMSO (0.1%) at 72 h (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of IL-10 production by GSK3-inactivated memory CD4+ T cells. A, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated with DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 (SB; 6 μM) for 2 h then transferred to plates precultured with PBS or immobilized anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml). IL-10 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR at the indicated time point and related to the levels of the endogenous housekeeping gene, GAPDH, at the respective time point. B, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated in medium, medium containing DMSO (0.1%), or medium containing SB216763 (6 μM) for 2 h and then transferred to plates coated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml). The kinetics of IL-10 production was assessed by analyzing the supernatants on the indicated day by ELISA. C, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated with DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 for 2 h and then stimulated with the indicated concentration of immobilized anti-CD3 and analyzed for IL-10 production by ELISA on day 4. Results are mean values ± SEM of triplicate cultures and representative of three individual experiments. *, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

We next examined the kinetics of IL-10 production by memory CD4+ T cells upon GSK3 inactivation. Significantly higher levels of IL-10 were present in supernatants derived from GSK3-inactivated memory CD4+ T cells than in cells stimulated in the presence of 0.1% DMSO or medium alone on day 3 (Fig. 5B). No difference in the kinetics of IL-10 production between GSK3-inactivated or DMSO (0.1%)-treated memory CD4+ T cells was observed (Fig. 5B). GSK3 inhibition increased IL-10 levels at all concentrations of anti-CD3 tested and the magnitude of IL-10 produced upon GSK3 inhibition was dependent on the strength of the TCR signal (Fig. 5C). Thus, rather than regulate the kinetics of IL-10 production, GSK3 regulates the magnitude of the IL-10 response upon TCR stimulation by memory CD4+ T cells.

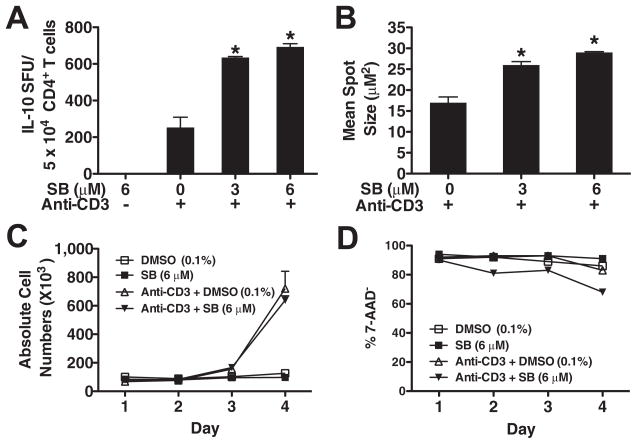

Repression of GSK3 activity enhances the productivity and frequency of IL-10-producing memory CD4+ T cells

We next assessed the regulation of IL-10 production by GSK3 at the single-cell level by ELISPOT which measures the secretion of IL-10 throughout the entire duration of the assay. Upon GSK3 inhibition, the frequency of IL-10-producing cells significantly increased by ~300%, as compared with anti-CD3-treated cells (Fig. 6A). GSK3 inhibition also significantly increased the net amount of IL-10 produced per cell (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the absolute number of IL-10-producing memory CD4+ T cells induced upon GSK3 inhibition increased with stronger TCR signals (data not shown). Similar results were obtained by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry (data not shown). Although at the concentration of anti-CD3 used we did not observe any significant change in memory cell proliferation, GSK3 may be effecting memory cell survival and thus influencing IL-10 production. No significant difference in the absolute number of memory CD4+ T cells was observed between day 1 and day 4 postactivation between memory CD4+ T cells activated in the presence or absence of GSK3 inhibition (Fig. 6C). In addition, no net increase in the survival of memory CD4+ T cell survival was observed upon GSK3 inactivation (Fig. 6D). Thus, although GSK3-inactivation augments the frequency and productivity of IL-10 expressing memory CD4+ T cells, these effects are not the result of an influence on cellular expansion or survival by GSK3.

FIGURE 6.

GSK3 inactivation increases the frequency and productivity of IL-10-producing, TCR-activated memory CD4+ T cells. A, Memory CD4+ T cells were pre-treated with DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 (SB; 6 μM) for 2 h and then transferred to plates containing immobilized anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and analyzed for spot-forming units (SFU) by ELISPOT on day 4. B, Memory CD4+ T cells cultured and activated as in A were analyzed for mean spot size by ELISPOT. C, Memory CD4+ T cells were pre-treated in medium containing DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 (6 μM) for 2 h and then transferred to plates coated with PBS or anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml). On the indicated day, absolute cell numbers for each well were determined using a hemocytometer. D, Memory CD4+ T cells were pretreated in media containing DMSO (0.1%) or SB216763 (6 μM) for 2 h and then transferred to plates coated with PBS or anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml). On the indicated day, cells were stained with 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean values ± SEM of triplicate cultures and representative of three individual experiments. *, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

GSK3 inactivation promotes IL-10-dependent regulatory activity

High IL-10 producing CD4+ T cells can suppress bystander T cell proliferation in an IL-10-dependent, cell contact-independent manner (22). To determine whether GSK3 inhibition promotes regulatory activity via IL-10, cell-free supernatants from activated memory CD4+ T cells stimulated in the presence or absence of GSK3 inhibition were transferred to CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7). CD4+ T cells stimulated in the presence of supernatants derived from activated memory CD4+ T cells in which GSK3 was inactivated exhibited significantly decreased proliferation, as compared with cells cultured in supernatants derived from memory cells stimulated with anti-CD3 alone (Fig. 7). Blocking the IL-10 receptor on the target cells (Fig. 7A) or neutralizing IL-10 (Fig. 7B) significantly reversed the suppressive capacity of the supernatants derived from memory cells activated in the presence of GSK3 inhibition, demonstrating the suppression was dependent on IL-10. The IL-10-dependent suppressive capacity of GSK3-inactivated memory CD4+ T cells was observed at suppressor-to-responder cellular ratios of 5:1 and 1:1 but was insignificant at a ratio of 1:5 (Fig. 7A). In addition, supernatants derived from nonstimulated cells in which GSK3 was inhibited were unable to suppress CD4+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 7B). Thus, the inactivation of GSK3 upon TCR stimulation can promote IL-10-dependent regulatory activity by human memory CD4+ T cells.

FIGURE 7.

GSK3-inactivated memory CD4+ T cells exhibit IL-10-dependent, cell contact-independent suppressor activity. A, Anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ T cells (responder cells) were cultured with cell-free supernatants derived from previously cultured memory CD4+ T cells (x-axis, culture conditions for suppressor population). Target cells were pre-incubated with anti-IL-10R1 or control Abs 30 min before the addition of the indicated supernatant. B, Anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ T cells (responder cells) were cultured with cell-free supernatant derived from previously cultured memory CD4+ T cells (x-axis, culture conditions for suppressor population) at a suppressor-to-responder ratio of 1:1. Anti-IL-10 or control Abs were added to the supernatants immediately before culturing with responder cells. A and B, Amount of BrdU uptake of the responder populations during the last 20 h of a 4-day culture. Results are mean values ± SEM of triplicate cultures and are representative of five experiments. *, p < 0.05 determined by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test.

Discussion

We demonstrate a contrast between human naive and memory CD4+ T cells in that inactivation of GSK3β strongly favors proliferation in naive cells whereas in memory CD4+ T cells it favors IL-10 production. The ability of GSK3 to enhance IL-10 levels by memory CD4+ T cells resulted in their ability to suppress bystander T cell proliferation in an IL-10-dependent manner.

The finding that GSK3 regulates NF-AT was the first study to demonstrate GSK3 was a component of the cellular signaling machinery present in cells of the immune system (23). Subsequent work performed with human and mouse cells implicated GSK3 as a negative regulator of T cell proliferation and IL-2 production (10, 13). Moreover, GSK3 was later found to regulate p27kip1 levels and the phosphorylation state of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein in the presence of TCR activation, thus adding mechanistic support for the role of GSK3 in T cell proliferation (9). However, because of the number of differences described in the intracellular signaling pathways present in naive and memory cells (3, 24), we hypothesized GSK3 may play discrete roles depending on the antigenic experience of the CD4+ T cell. In this regard, our findings identify the existence of a dichotomy present in the role of GSK3 in naive and memory human CD4+ T cells because GSK3 acts primarily as a negative regulator of proliferation in naive cells, whereas GSK3 inhibition in memory CD4+ T cells leads to enhanced IL-10 production and IL-10-dependent suppressive activity. The current findings clarify the role of GSK3 by demonstrating that the ability of GSK3 to negatively regulate proliferation is largely dependent on the antigenic experience of the CD4+ T cell.

Inhibition of GSK3β in memory CD4+ T cells increased IL-10 productivity upon TCR stimulation. The mechanism responsible for control of IL-10 by GSK3β in memory CD4+ T cells is unknown at the present. Various possibilities exist from the direct molecular regulation of IL-10 transcriptional activity (25) to indirectly by regulating activation-induced cell death (26) or cellular proliferation (10, 13). We explored the latter possibility that GSK3 may suppress IL-10 production by indirectly influencing the expansion or survival of memory CD4+ T cells postactivation. We found no evidence supporting this hypothesis. Specifically, we found that despite the ability of GSK3 to suppress the frequency of IL-10 producing cells present upon TCR activation, inactivation of GSK3 did not significantly alter the growth dynamics of activated memory CD4+ T cells as no significant increase in the percentage of viable cells or change in the absolute number of cells was observed throughout the duration of the assay. In contrast, increases in the steady-state levels of IL-10 mRNA were observed upon the inactivation of GSK3 suggesting that GSK3 either is involved in regulation of IL-10 mRNA stability or negatively controls a transcriptional event. The latter has been reported to be the mechanism by which GSK3 differentially controls pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production by TLR-stimulated monocytes (25). Specifi-cally, repression of GSK3 activity lead to a decrease in the transcriptional activity of NF-κB p65, an effect mediated by the ability of GSK3 to control nuclear CREB levels which compete with NF-κB p65 for the nuclear coactivator, cAMP-binding protein (25). Recently, the Epstein-Barr viral protein, LMP1, was shown to induce IL-10 production from B cells via a GSK3/CREB-dependent pathway (27). However, we did not observe any signifi-cant change in the transcriptional activity of CREB upon GSK3 inhibition in TCR-stimulated human peripheral blood T cells (C. A. Garcia, unpublished observation). Thus, although a commonality exists with TLR-stimulated innate immune cells, LMP1-expressing B cells, and TCR-stimulated memory CD4+ T cells with respect to the ability of GSK3 to suppress the production of IL-10 (25, 27–29), distinct differences are also apparent because GSK3 does not appear to regulate proinflammatory cytokine production by memory CD4+ T cells and the downstream mechanism for controlling IL-10 production appears to be unique in memory CD4+ T cells.

Although T cell differentiation is critical for the outcome of the adaptive immune response, the events regulating memory CD4+ T cell recall responses are likely to also be important, particularly in humans whose resident T cell population contains a considerable fraction of memory cells (30). Recent evidence suggests that despite diminished requirements of the memory CD4+ T cell on costimulation for proliferative responses and their ability to produce effector cytokines upon TCR stimulation alone (2), memory CD4+ T cells retain considerable plasticity and control with regard to their effector responses. To this accord, Sallusto et al. (31–33) have reported that human and murine CD4+ T cells, despite polarization into a specific lineage (i.e., Th1), can produce effector cytokines of a distinct and separate lineage (i.e., Th2) under particular conditions. The memory recall response has also been shown to be regulated by extrinsic factors like OX40, ICOS, and CD28 costimulation (6, 34, 35). Recently, it was shown that blockade of B7/CD28 signaling using CTLA-4Ig can inhibit the IL-2 and IFN-γ recall response of influenza-specific memory CD4+ T cells in mice (5) and that TLR stimulation and CD28 costimulation can augment IFN-γ production by TCR-stimulated human memory CD4+ T cells (36). Our finding that the level of endogenous GSK3 activity is a critical parameter involved in the regulation of the IL-10 recall response by human memory CD4+ T cells, taken together with our findings and those of others (37) demonstrating that the inhibition of PI3K activity abrogates IL-10 production by human memory CD4+ T cells, suggests that the ability of the PI3K pathway to regulate IL-10 production by human memory CD4+ T cells is due to its ability to inactivate GSK3. Indeed, blockade of PI3K activity abrogated the ability of anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation to induce the phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of GSK3 and promote IL-10 production by memory CD4+ T cells. Because the PI3K pathway can be induced in memory CD4+ T cells via distinct extrinsic signals like CD28, GSK3 may function as a molecular rheostat that regulates the amplitude of IL-10 production. Indeed, we demonstrate that CD28 costimulation can augment the production of IL-10 from TCR-stimulated memory CD4+ T cells in a PI3K-dependent manner. GSK3 may serve as a biochemical link between the state of the immunological milieu and the memory CD4+ T cell for the regulation of IL-10. The importance of GSK3 activity in in vivo IL-10 responses by memory CD4+ T cells responses should be explored in future studies.

Memory CD4+ T cells have been implicated in a vast number of autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, and type I diabetes mellitus (38). Yet despite their likely participation in diverse autoimmune pathologies, memory CD4+ T cells in many cases are resilient to therapeutic strategies shown to be successful with their naive counterparts (38). This resiliency has been attributed to qualities such as enhanced Ag sensitivity and lesser dependency on costimulation for their execution of effector responses. Although human memory CD4+ T cells can produce multiple effector cytokines upon TCR cross-linking alone, costimulatory molecules can still alter the memory CD4+ T cell recall response. However, strategies relying on costimulatory blockade may not always be effective when memory CD4+ T cells are a principal etiological agent because even in the absence of costimulation, memory CD4+ T cells are capable of producing Th1-, Th2-, and Th17-type cytokines. Our current work suggests that rather than inhibiting memory CD4+ T cell activation, an alternative approach for the modulation of memory CD4+ T cell responses may be feasible by targeting regulatory kinases such as PI3K and GSK3β that are intimately involved in the memory CD4+ T cell cytokine response. We demonstrate that although TCR-stimulated memory CD4+ T cells upon GSK3 inactivation can still produce proinflammatory cytokines, their propensity toward IL-10 production as a consequence of GSK3 inactivation, renders a state where the suppression of bystander CD4+ T cell proliferation is observed. Thus, GSK3 may provide a valuable target for modulating immune responses involving memory CD4+ T cells due to the unique ability of GSK3 to govern IL-10 production.

Acknowledgments

We thank Panagiota Stathopoulou and Kobe Garcia for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute of Dental Research Grant R01DE017680.

Abbreviations used in this paper: GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; 7-AAD, 7-aminoactinomycin D; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sharpe AH, Abbas AK. T-cell costimulation: biology, therapeutic potential, and challenges. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.London CA, Lodge MP, Abbas AK. Functional responses and costimulator dependence of memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:265–272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farber DL. Cutting edge commentary: differential TCR signaling and the generation of memory T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson ARO, Lee WT. Differences in signaling molecule organization between naive and memory CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;173:33–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ndejembi MP, Teijaro JR, Patke DS, Bingaman AW, Chandok MR, Azimzadeh A, Nadler SG, Farber DL. Control of memory CD4 T cell recall by the CD28/B7 costimulatory pathway. J Immunol. 2006;177:7698–7706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldrop SL, Davis KA, Maino VC, Picker LJ. Normal human CD4+ memory T cells display broad heterogeneity in their activation threshold for cytokine synthesis. J Immunol. 1998;161:5284–5295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pages F, Raqueneau M, Rottapel R, Truneh A, Nunes J, Imbert J, Olive D. Binding of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase to CD28 is required for T-cell signalling. Nature. 1994;369:327–229. doi: 10.1038/369327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad KVS, Cai YC, Raab M, Duckworth B, Cantley L, Shoelson SE, Rudd CE. T-cell antigen CD28 interacts with the lipid kinase phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by a cytoplasmic Tyr(P)-Met-Xaa-Met motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2834–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appleman LJ, van Puijenbroek AA, Shu KM, Nadler LM, Boussiotis VA. CD28 costimulation mediates down-regulation of p27kip1 and cell cycle progression by activation of the PI3K/PKB signaling pathway in primary human T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2729–2736. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diehn M, Alizadeh AA, Rando OJ, Liu CL, Stankunas K, Botstein D, Crabtree GR, Brown PO. Genomic expression programs and the integration of the CD28 costimulatory signal in T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11796–11801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092284399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li CR, Berg LJ. Cutting edge: Itk is not essential for CD28 signaling in naive T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:4475–4479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood J, Schneider H, Rudd CE. TcR and TcR-CD28 engagement of protein kinase B (PKB/AKT) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) operates independently of guanine nucleotide exchange factor VAV-1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32385–32394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohteki T, Parsons M, Zakarian A, Jones RG, Nguyen LT, Woodgett JR, Ohashi PS. Negative regulation of T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 production by the serine threonine kinase GSK-3. J Exp Med. 2000;192:99–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin M, Schifferle RE, Cuesta N, Vogel SN, Katz J, Michalek SM. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-Akt pathway in the regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2003;171:717–725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–776. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkenschlager M, Terry L, Edwards R, Beverley PC. Limiting dilution analysis of proliferative responses in human lymphocyte populations defined by the monoclonal antibody UCHL1: implications for differential CD45 expression in T cell memory formation. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1653–1661. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young JL, Ramage JM, Gaston JS, Beverley PC. In vitro responses of human CD45RObrightRA− and CD45RO−RAbright T cell subsets and their relationship to memory and naive T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2383–2390. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier LM, Anderson DE, De Jager PL, Wicker LS, Hafler DA. Allelic variant in CTLA4 alters T cell phosphorylation patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18607–18612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706409104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cross DA, Culbert AA, Chalmers KA, Facci L, Skaper SD, Reith AD. Selective small-molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity protect primary neurones from death. J Neurochem. 2001;77:94–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers PR, Dubey C, Swain SL. Qualitative changes accompany memory T cell generation: faster, more effective responses at lower doses of antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2238–2346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groux H, O’Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737–742. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beals CR, Sheridan CM, Turck CW, Gardner P, Crabtree GR. Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science. 1997:1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dienz O, Eaton SM, Krahl TJ, Diehl S, Charland C, Dodge J, Swain SL, Budd RC, Haynes L, Rincon M. Accumulation of NFAT mediates IL-2 expression in memory, but not naive, CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7175–7180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta S, Jayaraman P, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Unrestrained glycogen synthase kinase-3β activity leads to activated T cell death and can be inhibited by natural adjuvant. J Immunol. 2008;178:6083–6091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert SL, Martinez OM. Latent membrane protein 1 of EBV activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to induce production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2007;179:8225–8234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X, Paik PK, Chen J, Yarilina A, Kockeritz L, Lu TT, Woodgett JR, Ivashkiv LB. IFN-γ suppresses IL-10 production and synergizes with TLR2 by regulating GSK3 and CREB/AP-1 proteins. Immunity. 2006;24:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodionova E, Conzelmann M, Maraskovsky E, Hess M, Kirsch M, Giese T, Ho AD, Zoller M, Dreger P, Luft T. GSK-3 mediates differentiation and activation of proinflammatory dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;109:1584–1592. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saule P, Trauet J, Dutriez V, Lekeuz V, Dessaint JP, Labalette M. Accumulation of memory T cells from childhood to old age: central and effector memory cells in CD4+ versus effector memory and terminally differentiated memory cells in CD8+ compartment. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;127:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messi M, Giacchetto I, Nagata K, Lanzavecchia A, Natoli G, Sallusto F. Memory and flexibility of cytokine gene expression as separable properties of human Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:78–86. doi: 10.1038/ni872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundrud MS, Grill SM, Ni D, Nagata K, Alkan SS, Subramaniam A, Unutmaz D. Genetic reprogramming of primary human T cells reveals functional plasticity in Th cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2003;171:3542–3549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmadzadeh M, Farber DL. Functional plasticity of an antigen-specific memory CD4 T cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11802–11807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192263099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito T, Wang YH, Duramad O, Hanabuchi S, Perng OA, Gilliet M, Qin FX, Liu YJ. OX40 ligand shuts down IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13138–13143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603107103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salek-Ardakani S, Song J, Halteman BS, Jember AG, Akiba H, Yaqita H, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) controls memory T helper cells that drive lung inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:315–324. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caron G, Duluc D, Fremaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, Delneste Y. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-γ production by memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1551–1557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto N, Tezuka K, Kato M, Abe R, Tsuji T. PI3-kinase and MAP-kinase signaling cascades in AILIM/ICOS- and CD28-costimulated T-cells have distinct functions between cell proliferation and IL-10 production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ndejembi MP, Tang AL, Farber DL. Reshaping the past: strategies for modulating T-cell memory immune responses. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]