Abstract

Purpose

This is the first study describing the tobacco industry’s objectives developing and publishing lifestyle magazines, linking them to tobacco marketing strategies, and how these magazines may encourage smoking.

Methods

Analysis of previously secret tobacco industry documents and content analysis of 31 lifestyle magazines to understand the motives behind producing these magazines and the role they played in tobacco marketing strategies.

Results

Philip Morris (PM) debuted Unlimited in 1996 to nearly 2 million readers and RJ Reynolds (RJR) debuted CML in 1999 targeting young adults with their interests. Both magazines were developed as the tobacco companies faced increased advertising restrictions Unlimited contained few images of smoking, but frequently featured elements of the Marlboro brand identity in both advertising and article content. CML featured more smoking imagery and fewer Camel brand identity elements.

Conclusions

Lifestyle promotions that lack images of smoking may still promote tobacco use through brand imagery. The tobacco industry still uses the “under the radar” strategies used in development of lifestyle magazines in branded websites. Prohibiting lifestyle advertising including print and electronic media that associate tobacco with recreation, action, pleasures, and risky behaviors or that reinforces tobacco brand identity may be an effective strategy to curb young adult smoking.

Keywords: Tobacco, Marketing, Lifestyle Advertising, Content Analysis, Young Adults

INTRODUCTION

Young adults ages 18–24 have the highest smoking prevalence compared to other age groups in the United States [1]. During young adulthood many people either make the transition from occasional use to addiction or stop smoking [2, 3]. Tobacco industry marketing aggressively targets young adults [4, 5], and marketing to this group is largely unrestricted in the United States [6]. Receptivity to tobacco advertising [7] and exposure to tobacco promotional activities [8] are associated with young adult tobacco use.

One promotional strategy that has not been examined previously is tobacco industry-produced lifestyle magazines. During the 1990s and 2000s, lifestyle magazines were a tool other companies used for marketing purposes [9, 10]. Tobacco companies developed their own lifestyle magazines [11, 12] in part to nurture closer relationships with young adults [10, 11]. The magazines generated sales for tobacco products [13, 14], their distributions were comparable or exceeded those of other lifestyle magazines [15–17], and young adult exposure to these magazines was high [11, 18]. For nearly ten years, tobacco companies continued to produce lifestyle magazines through controlled distribution via direct mail databases and, therefore, out of sight of most public health professionals.

We analyzed both previously secret tobacco industry documents and lifestyle magazine content to explore five broad questions: Why did tobacco companies produce their own lifestyle magazines? Who were their intended targets? What role did their lifestyle magazines play in tobacco marketing strategies? Were these lifestyle magazines successful? How was success measured? In our content analysis, we consider two specific hypotheses to support our research questions: the tobacco industry-produced lifestyle magazines promote smoking by depicting positive images of smoking, and that the magazines operate as brand vehicles by connecting the brand identity to the lifestyles and interests of young adults.

Understanding how these magazines reinforce smoking is useful for clinicians and public health professionals who want to understand why young people smoke and how to motivate them to stop.

METHODS

We searched tobacco industry document archives from the University of California, San Francisco Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (legacy.library.ucsf.edu), and Tobacco Documents Online between February 2006 and December 2007. Initial search terms included: Marlboro; Unlimited; Camel; CML; young adult; brand identity; and brand plan. Initial searches yielded thousands of documents; we reviewed documents related to custom publication development. Searches were repeated and focused using standard techniques [19], including “snowball” searches for contextual information using key words, names, project titles, dates, and reference (Bates) numbers. This analysis is based on a final collection of 337 research reports, presentations, memoranda, and brand plans. We reviewed the documents, organized them thematically, and wrote summary memoranda. Information found in industry documents was triangulated with data from searches of the published literature, online search engines, news stories, and examination of promotional materials. We found the most complete planning documents for PM’s Marlboro-branded Unlimited (Figure 1) and RJ Reynolds’ (RJR) Camel-branded CML (Figure 2), two of the most popular and most aggressively promoted brands for young adult males.

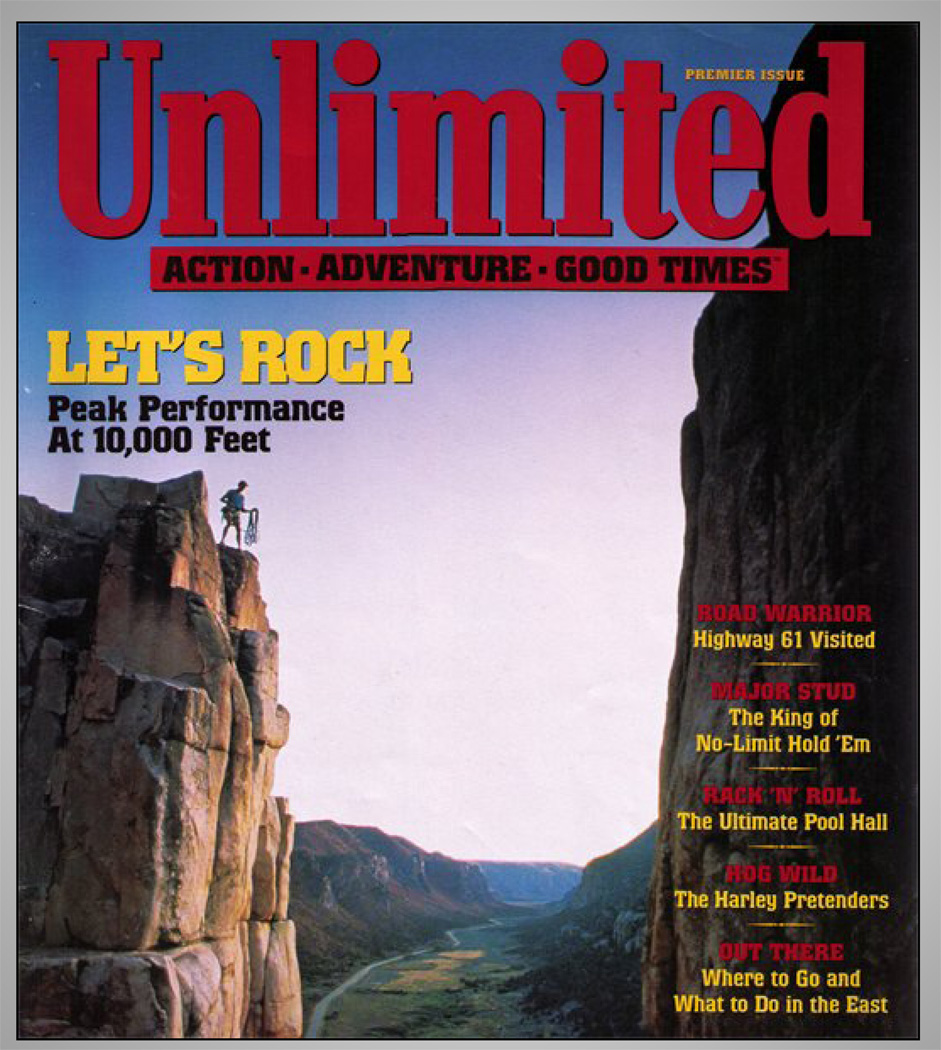

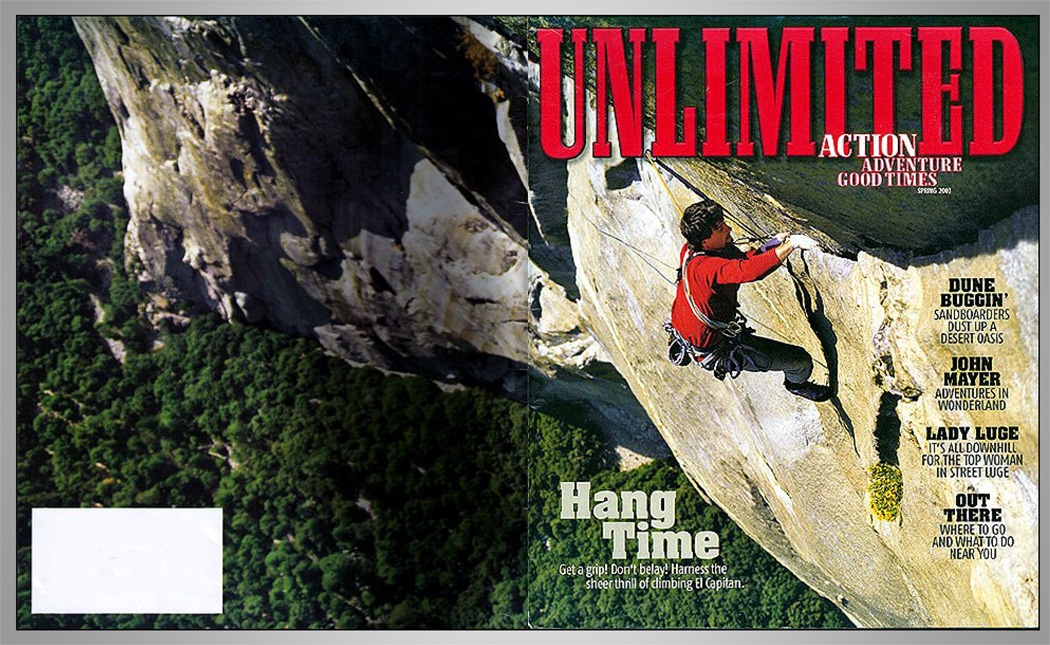

Figure 1. Premier Issue of Unlimited.

Philip Morris debuted the Marlboro-branded Unlimited in Fall 1996 by controlled circulation to nearly 2 million young adults taken from their names database.

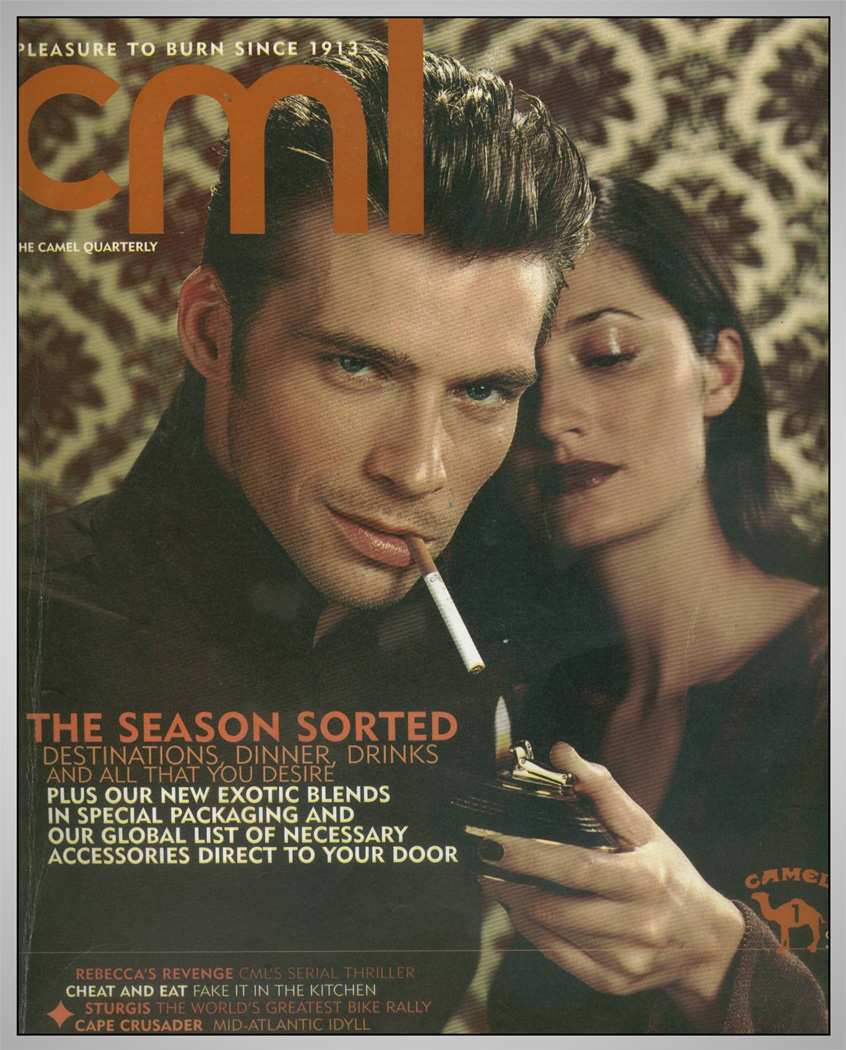

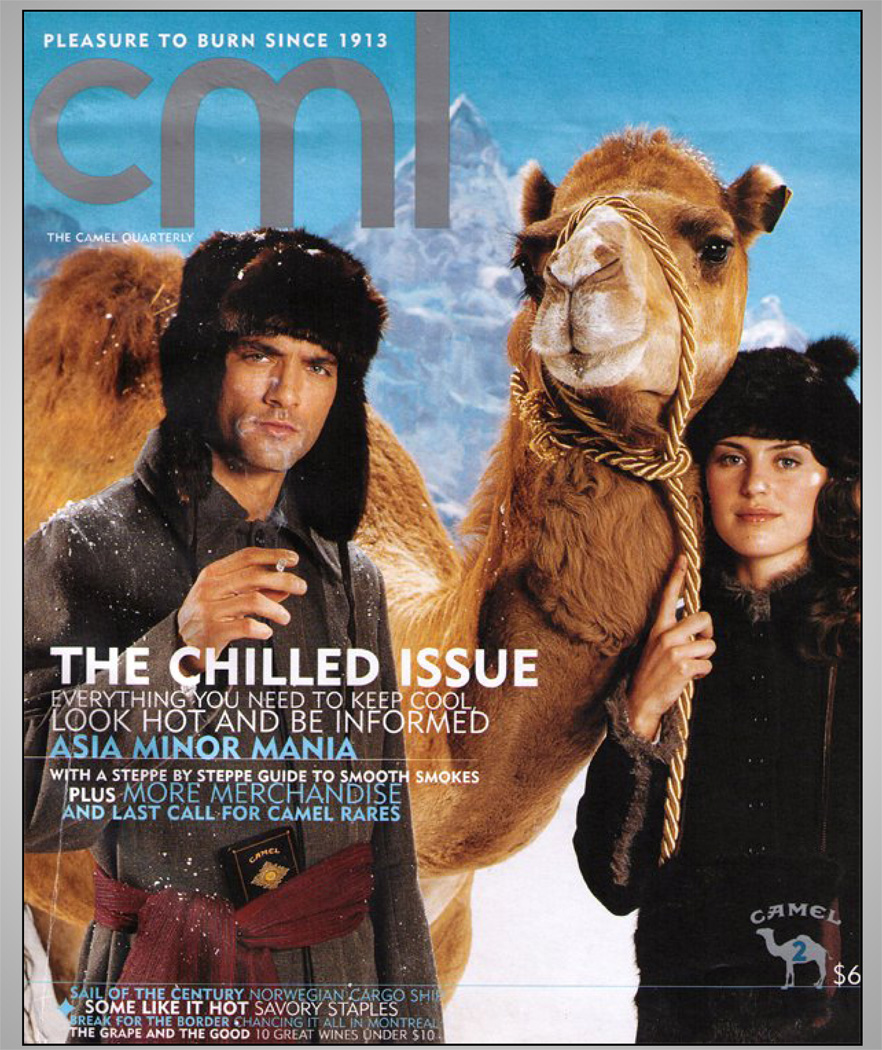

Figure 2. Premier Issue of CML.

RJ Reynolds debuted CML in Fall 1999, describing it as a “magalog”: part magazine, part catalog for Camel cigarettes and lifestyle accoutrement.

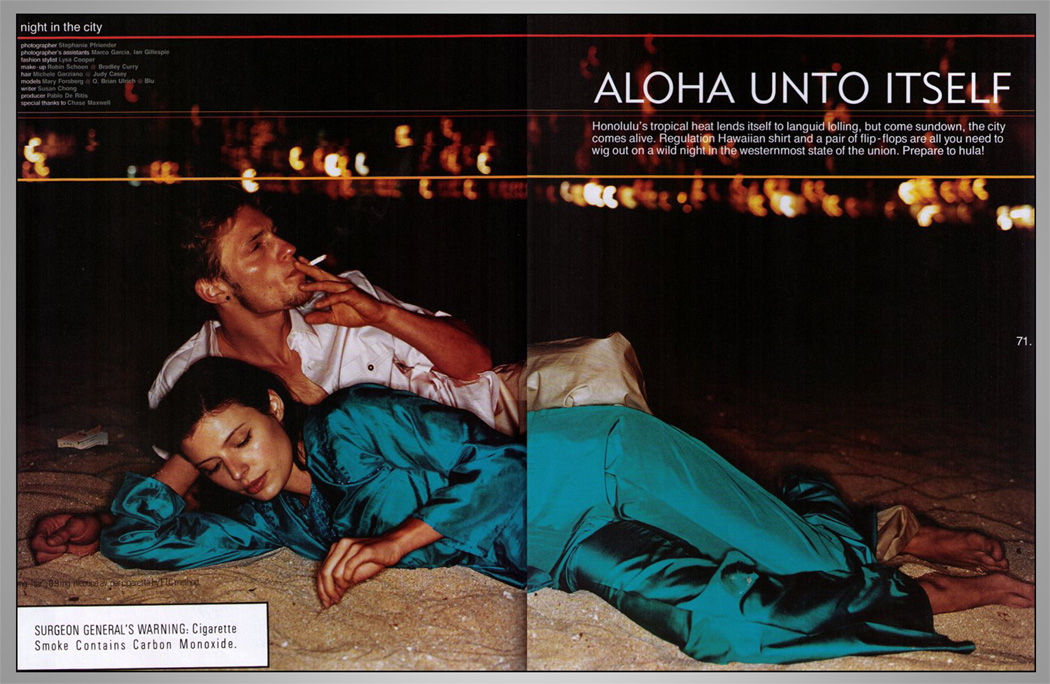

We analyzed 25 Unlimited and 6 CML magazine issues housed at Trinkets and Trash (trinkestsandtrash.org), an archive and surveillance system of historic and current tobacco promotional materials. The magazines analyzed contained a total of 732 articles, 181 tobacco ads, and 528 non-tobacco ads. We defined a tobacco advertisement as an item with a visible Surgeon General’s warning label or an FTC statement specifying the amount of “tar” and nicotine in the cigarette, and as a non-tobacco advertisement if it advertised products that were not for tobacco, including tobacco paraphernalia (e.g., lighters, ashtrays). Although most CML advertisements were tobacco ads, these were mostly advertorials (both advertisement and editorial), and were counted as tobacco advertisements (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CML “Advertorial” (Spring 2000).

RJ Reynolds discreetly placed Camel cigarettes in the images throughout CML articles. In this case, the Camel cigarette in the man’s hand and the Surgeon General’s Warning label and FTC Statement refer to the pack of Camels in the sand next to his shoulder. The Surgeon General’s Warning label and FTC Statement suggest this is an advertisement within editorial content; In other words, an “advertorial.”

We developed coding instruments to analyze the magazine for smoking and brand identity content in four areas: Covers, articles, tobacco advertisements, and non-tobacco advertisements. We trained five coders using standard methods [20]. Coders were blinded to our hypotheses, and coded the frequency of references or depictions of tobacco or its use, tobacco products, logos, or brand names, and cover elements. We measured intercoder reliability formally using Krippendorff’s Alpha (0.704) and raw percentages of agreement (greater than 80%), both of which are acceptable reliability levels for content analyses that include more than two coders [20, 21].

Our analysis of industry documents suggested two hypotheses that we tested by content analysis. First, we hypothesized that the content in Unlimited and CML portray smoking or smokers positively. Second, we hypothesized that the content in Unlimited and CML reflect the Marlboro and Camel brand identities, which is how marketers want a brand to be perceived by consumers [22].

Key elements of the brand identity identified from our analysis of internal marketing documents were identified and incorporated into our coding instruments using a four-point Likert scale. Coders based their ratings of themes (e.g., tough or rugged) on an overall assessment of the entire article based on marketers’ definitions of brand identity components, which at times were vague. Our definitions, therefore, were reliable but may have been different from the marketer’s original intent. We combined components that appeared to have similar definitions to facilitate coder reliability and validity.

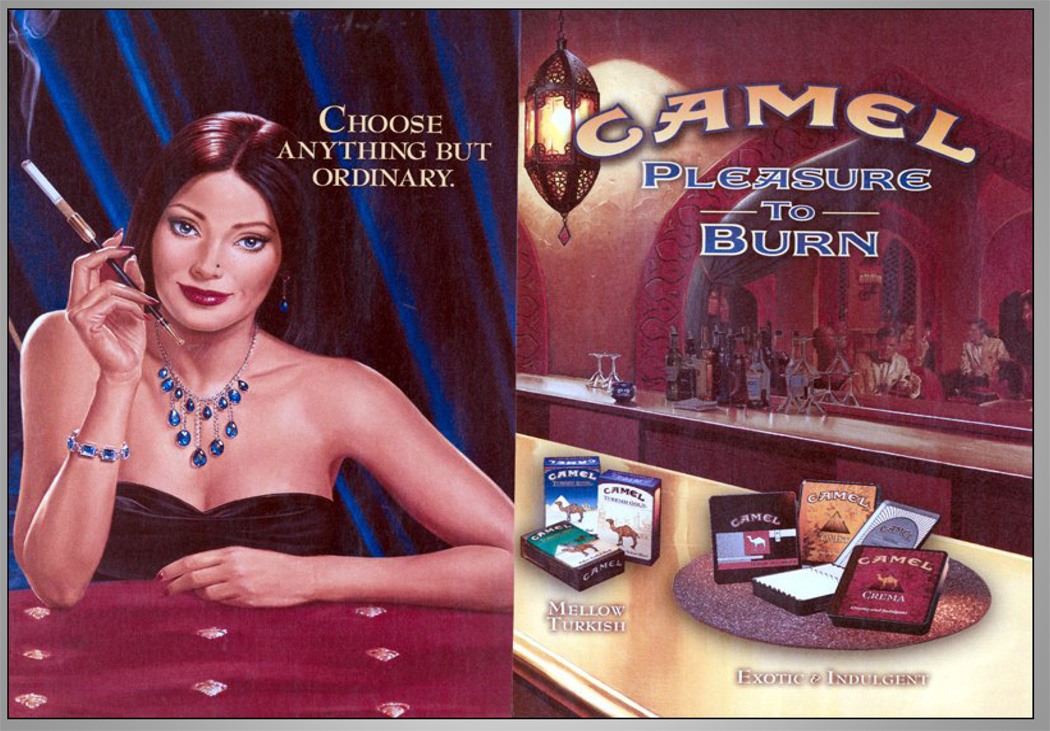

The “Marlboro brand score” included elements that PM marketers sought to associate with the Marlboro brand: Tough or Rugged [23, 24], Solitude, Freedom, or Independence [23, 24], Rural or Harmony with Nature [23, 24], Classic, Traditional, or Nostalgic [23, 24], and Adventure or Excitement [23, 24]. The “Camel brand score” included components of the Camel brand identity: Tough or Rugged [overlapping category with Marlboro][25], Irreverence or Sassiness [25, 26], Urban [Reverse coding of Rural or Harmony with Nature] [25], Classic, Traditional, or Nostalgic [overlapping category with Marlboro][26, 27], Contemporary, Modern, or Trendy [25, 26], Edgy or Rebellious [25, 26], and Sociable [28]. The Camel brand score included RJR’s attempts to integrate classic with modern imagery (e.g., Figure 4). The distribution of each brand identity element and total Marlboro and Camel brand scores were calculated for all articles and advertisements. A “high” brand score was defined based on the top quartile of the score distribution.

Figure 4. Camel Advertisement in CML ( Winter 2003).

The Camel advertisements in CML seam together the classic with the modern. In this advertisement, the exotic-looking woman features a classic-style hairstyle and cigarette holder, but whose nose ring and revealing outfit evoke a more modern feel.

RESULTS

Socio-political context of magazine development

During the 1990s, tobacco companies faced strong regulatory threats by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that would have limited tobacco advertising in print publications that reached youth (children and adolescents) [29, 30]. In August 1995, President Bill Clinton directed FDA Director David Kessler to place the sale, distribution, and use of tobacco products under FDA regulatory control [31]. Tobacco companies internally expressed concern about the proposed regulations [32, 33], and filed lawsuits challenging the FDA’s proposal, which they eventually won in a 2000 US Supreme Court decision [34]. In 1998, PM signed the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), which prohibits targeting youth in tobacco marketing, advertising, and promotions.

While fighting efforts to limit tobacco advertising, PM and RJR developed new lifestyle magazines for young adults. Unlike previous tobacco industry publications, lifestyle magazines presented bold images, witty minutiae, and many advertisements for alcohol, tobacco, and “cool” accoutrements salient to young adults. A 1994 letter between the publisher Hachette Filipacchi and Philip Morris portends the allure of lifestyle magazines to young adults: “No one in the cigarette industry has used [lifestyle magazines] to conquest or keep a consumer. It is unique and terribly impactful [sic]” [10].

Unlimited Magazine: “Marlboro Country in Action”

Philip Morris (PM) and publisher Hachette Filipacchi Magazines (HFM) developed the quarterly publication Unlimited between 1994 and 1996 to reflect the Marlboro brand and distributed it for free quarterly to nearly 2 million young adults between its 1996 launch and at least 2005 [18, 35, 36, 37, 1999 #303]. The earliest discussion of Unlimited is in 1994 when Nancy Lund, the VP of Brand Management for Marlboro received a custom publication concept pitch, in which HFM Vice President Susan Buckley argued that “magazine communication gains momentum unlike promotions that need reinvention every year” [10].

In October 1994, HFM signed a confidentiality agreement with PM to develop Unlimited [38]. PM approved major editorial content [39–42], but the PM or Marlboro names were excluded from the masthead [43] because PM did not want Unlimited “to be perceived immediately as a complete Marlboro vehicle” [37, 43]. PM considered positioning Unlimited as indistinguishable from other lifestyle magazines [44–46]. The publishing cost per quarter for Unlimited was $3.1 million in 1999 [12]. PM developed media kits [44, 46–48] for HFM to use for soliciting “advertising space exclusively to advertisers of products for adults, including alcoholic beverages” [39] like Bacardi, Smirnoff, and Jack Daniels [47], as well as young adult-oriented, name-brand audio electronics, outdoor gear, motorcycles, and hygiene and health products [47–49].

Early in the development process, the Looking Glass Group (LGG) conducted three phases of focus groups (Table 1) with young male smokers ages 21 – 29 about the magazine concept [50, 51], and the prototype was revised after each phase [50]. The resulting report stated that Unlimited accurately reflected the activities and interests of a particular target population of Marlboro who “do not…take a broad, intellectual interest in the world around them. …Most seem to prefer spending a free evening with their buddies in a bar, drinking, smoking, chasing women, playing darts, shooting pool…or, as a last resort, spend time with their wives or girlfriends” [50].

Table 1.

Summary of PM Research on Unlimited

| Study | Purpose of study | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Production Market Research | 1995 YAMS Focus Groups [50, 59] |

|

|

| 1995 YAFS Focus Group [62] |

|

||

| Unlimited Reader Surveys | Fall 1998 [52] |

|

|

| Fall 1999 [53, 64] |

|

|

PM financed reader surveys (Table 1) to measure the awareness of, attitudes toward, and impressions of Marlboro’s brand character in Unlimited. Beginning in the Spring 1997 issue of Unlimited, and continuing in every fall issue from 1998 until at least 2003, PM researched reader perception of Unlimited [52–56]. A 1998 reader survey found that Unlimited captured the outdoorsy, rural, adventurous, and rugged essences of Marlboro branding [52]. The high article recall [52, 57], the multiple readers of Unlimited other than the recipient [52, 58], and Unlimited’s positive influence on the perception of the Marlboro brand [35, 57], suggest that Unlimited was an influential brand vehicle to millions of young adults.

PM measured Unlimited readers’ interest in Internet and computers [65–67] and data from these surveys were used to solicit advertisers [68]. In 2000, PM planned augmenting Unlimited with a CD-ROM to keep it “fresh and interactive” [36]. In 2002, a major revision of Unlimited modified the cover “to incorporate more Marlboro…branding” [69], and considered whether readers should “know [Unlimited] is from Marlboro at a glance” [70], by including the familiar Marlboro font and color into the title (Figure 5). These modifications are confirmed by our content analysis findings discussed in the next section.

Figure 5. Vista on Cover of Unlimited.

The Marlboro font and the vista suggest to the reader that the cover of Unlimited is a Marlboro advertisement. Previous covers depicted a Marlboro advertisement on the back, but the Spring 2003 cover and subsequent ones expanded the outdoor vista to the back cover and used the Marlboro font in the title.

We did not find any documents pertaining to the demise of Unlimited. A November 2004 newspaper article announced the end of Unlimited, citing a “marketing change” in PM [71]. The last issue identified was Winter 2005 (Figure 7). No issue referenced a Marlboro brand website.

Figure 7. Camel-branded CML Cover (Winter 2000).

Images of camels abound on the CML covers, whether it is the Camel cigarette pack in the waist sash of the man, the Camel logo in the lower-right corner next to the “price” of the magazine, or the actual dromedary. Documents suggest that CML was distributed gratis to young adults in the RJ Reynolds’ names database.

CML Magazine: Camel’s “Bridge to the Future”

In 1999, RJ Reynolds (RJR) debuted its lifestyle custom publication under the title CML emphasizing music, fashion, and urban nightlife interests [72]. CML was distributed via direct mail [11] and linked to RJR’s Camel brand [72] and their bar and club promotions [25]. An anonymous document dated March 1996 expressed concern about possible FDA regulations whereby RJR would have been precluded “from running [advertisements] in a majority of magazines which reach 21 – 34 [year old] smokers…[and] could continue to run image/color ads in only about 3%” of the periodicals RJR advertised in during 1996 [73]. The document recommended developing alternative print media options for RJR brands [73].

G. N. “Nick” Kuruc, Key Account Manager at RJR, stated that the magazine would be a “bridge to the future” [74] by fully integrating the Camel brand identity” into the content [25, 74]. The “no apologies” tone would convey a “lust for living with an urban nightlife emphasis” to be relevant to the lives and interests of young adults [11].

RJR’s long-term goal was to create a magazine that would be a revenue source for both Camel and the custom publisher [28]. In 1996, RJR solicited proposals from publishers of magazines in which they advertised Camel, such as Playboy, Maxim, and Rolling Stone [75–77] to create custom publications for RJR brands [78]. RJR marketing executives were aware of PM’s Unlimited magazine in 1996 [79], and actively evaluated Unlimited in 1998 [11, 15, 80]. An email from Rick Gray, the Camel Brand Marketing Assistant stated that Unlimited magazine is “alarmingly similar to the…Camel Magazine and quite a departure from what [PM has] done in the past” [80]. RJR planned the Camel magazine to take an “under the radar” approach in its “targeted and relevant brand identity communication”[11].

In 1998, Playboy Publishing developed prototypes titled Zipper [81, 82] and Moxie [83]. RJR tested the magazine prototype against Unlimited among young males and females [84], who agreed it was “in the company of other ‘on the edge’ publications, such as Spin, Details, [and] Rolling Stone…”[85].

Paul Knouse, a senior manager in marketing, advised that RJR “should be very careful about putting… too much [Camel] emphasis in the publication…[because it] might make the magazine look promotional and perhaps ‘self-serving’ to Camel” [85]. Unlimited was criticized in the focus groups because it “was viewed as…a ‘giant ad for Marlboro’” [85]. RJR marketers did not appear to heed Knouse’s advice and, instead, opted to make CML “even more integrated with Camel and the world of Camel” [86].

RJR eventually chose Winkmedia, a division of Time-Warner and producer of Wallpaper* magazine, to publish their custom publication in late-1999 [87]. Titled CML to fit “Camel’s position and personality (irreverent, …modern, and edgy), and [to be] reminiscent of the brand name” [87], CML was both a magazine and catalog or, what RJR coined a “magalog” [87].

We do not know of RJR’s assessment of the success of CML, nor did we find any documents specifying the demise of CML. The last issue in the collection is Winter 2003. One document stated that making “a website out of [CML]…will definitely be our next step” [88], but no additional planning documents state the CML website idea was implemented. Every CML had multiple references to the telephone number to purchase Camel products, but did not refer the reader to a Camel-branded website.

Content Analysis

We find qualitatively that the covers of Unlimited and CML are similar to the Marlboro and Camel brands, respectively. Unlimited typically included an article “teaser” on the front cover that referenced a celebrity or sports figure (Figure 1, Figure 5, & Figure 6). In the 16 Unlimited covers where gender and number could be determined, men alone or in a group of two were depicted most often, while CML most often pictured a male/female couple (Table 2). These findings are consistent with the goals PM stated in planning documents to use images strikingly similar to Marlboro advertisements of men interacting with nature in panoramic vistas (Figure 1, Figure 5 & Figure 6), and use the Marlboro colors and font (Figure 5). CML covers display the earthy, desert colors of the Camel brand identity, but do not use Camel font, instead opting for overt Camel images like Camel logos, products, and in one case, an actual dromedary (Figure 7).

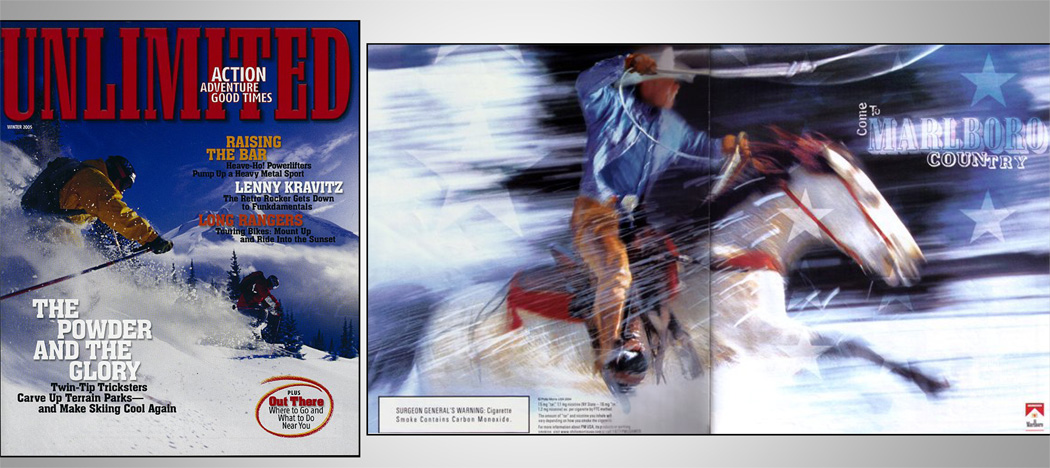

Figure 6. Cover of Final Issue of Unlimited Compared with Marlboro Advertisement Inside the Front Cover.

The cover of the Winter 2005 magazine (Left), with the snow-capped mountain vista and active downhill skiers looks strikingly similar to the Marlboro advertisement (Right) found in the inside cover.

Table 2.

Composition of Unlimited and CML

| Unlimited | CML | |

|---|---|---|

| Text on Cover Mentions Celebrity or Sports Figure % (n) |

68.0% (17) |

-- |

| Gender of People on Cover, Men Only % (n) |

100.0% (16) |

33.3% (2) |

| Gender of People on Cover, Equal Number Women and Men % (n) |

-- | 66.7% (4) |

| Number of People on Cover, One Person % (n) |

43.8% (7) |

33.3% (2) |

| Number of People on Cover, Two People % (n) |

37.5% (6) |

66.7% (4) |

| Number of People on Cover, Three or More People % (n) |

18.8% (3) |

-- |

| Tobacco Use on Cover % (n) |

-- | 100.0% (6) |

| Tobacco Use in Article % (n) |

1.4% (9) |

30.0% (36) |

| Tobacco Use in Tobacco Advertisement % (n) |

26.5% (18) |

51.3% (58) |

| Tobacco Use in Non-Tobacco Advertisement % (n) |

1.5% (8) |

-- |

Unlimited and CML differed in article topics; the most frequent article topics in Unlimited were among the least frequent topics in CML, and vice versa (Table 3). Over 30 percent of the articles in CML were coded as tobacco catalogs (Table 3), defined as a tobacco product list with an adjacent product picture, brief description, price, and purchase instructions, which we would expect given that CML was a “magalog.” Both Unlimited and CML included articles about travel emphasizing young adult music or nightclub scenes.

Table 3.

Most Frequent Articles in Unlimited and CML Magazines, By Topic

| Unlimited (N=633) | CML (N=139) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sports/Competition | 16.1% | 3.6% |

| Automobiles/ Motorcycles |

12.2% | 1.4% |

| Celebrity News & Interviews |

10.4% | 0.0% |

| Travel or Tourism | 7.3% | 8.6% |

| Profiles or Career Profiles |

5.5% | 6.5% |

| Nightlife | 0.8% | 7.9% |

| Catalog: Tobacco | 0% | 27.3% |

| Catalog: Other | 0% | 5.8% |

Percent of All Articles Does not add up to 100% because certain low frequency topics were not included in the table.

CML was more likely than Unlimited to advertise tobacco using multiple page advertisements, which could reflect the “advertorial” design of tobacco advertisements. Non-tobacco advertisements were prevalent in Unlimited and non-existent in CML (Table 2), and were typically items of interest to young adult men (Table 4). CML depicts tobacco use throughout the magazine far more frequently than Unlimited (Table 2 and Figure 3). These data comport with our documents analysis findings that PM intended Unlimited to appear as a “legitimate” magazine and that RJR intended CML to advertise tobacco products.

Table 4.

Most Frequent Category of Non-Tobacco Product Advertisements in Unlimited

| Product Category | Unlimited % (n) |

|---|---|

| Automotive and Motorcycles | 33.0% (174) |

| Electronics | 15.2% (80) |

| Clothing, Shoes, and Fashion Accessories | 9.8% (52) |

| Sports Equipment or Products | 8.5% (45) |

| Alcohol | 7.0% (37) |

Does not add up to 100% because low frequency categories were not included in the table.

We calculated agreement to each component of the Marlboro and Camel scores to measure how closely articles, tobacco advertisements, and non-tobacco advertisements in Unlimited and CML, reflected the respective brand identities (Table 5). In Unlimited we found that most of the tobacco advertisements and many of the articles in Unlimited scored high on the Marlboro brand score. Unlimited’s non-tobacco ads did not score high on Marlboro brand scores. In CML, we found that the articles and tobacco advertisements did not score high on the combined Camel brand scores for all seven components (Table 5). CML scored high on individual Camel brand score components, such as contemporary and urban. Our content analysis data suggest that the branding executed in CML may have been different from the original brand plans discussed earlier in the documents analysis.

Table 5.

Calculated Marlboro & Camel Scores for all Articles and Advertisement!

| Articles % Agree (n) |

Tobacco Ads % Agree (n) |

Non-Tobacco Ads % Agree (n) |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marlboro-Branded Unlimited |

Marlboro Score % Agree in Top Quartile (n) |

32.2% (211) |

69.1% (47) |

14.8% (78) |

26.8% (336) |

| Tough or Rugged | 40.1% (263) |

75.0% (51) |

25.8% (136) |

35.9% (450) |

|

| Solitude, Freedom, or Independence |

16.5% (108) |

54.4% (37) |

22.0% (116) |

20.8% (261) |

|

| Rural or Harmony with Nature | 36.6% (240) |

63.2% (43) |

17.0% (90) |

29.8% (373) |

|

| Classic, Traditional, or Nostalgic | 16.0% (105) |

66.2% (45) |

14.6% (77) |

18.1% (227) |

|

| Adventure or Excitement | 49.5% (325) |

38.2% (26) |

16.5% (87) |

35.0% (438) |

|

| Camel-Branded CML |

Camel Score % Agree in Top Quartile (n) |

31.6% (24) |

22.1% (25) |

-- | 25.9% (49) |

| Tough or Rugged | 34.2% (26) |

10.6% (12) |

-- | 20.1% (38) |

|

| Irreverence or Sassiness | 31.6% (24) |

12.4% (14) |

-- | 20.1% (38) |

|

| (Reverse coding) Rural or Harmony with Nature |

60.5% (46) |

89.4% (101) |

-- | 77.8% (147) |

|

| Classic, Traditional, or Nostalgic | 25.0% (19) |

27.4% (31) |

-- | 26.5% (50) |

|

| Contemporary, Modern, or Trendy |

84.2% (64) |

79.6% (90) |

-- | 81.5% (154) |

|

| Edgy or Rebellious | 5.3% (4) |

1.8% (2) |

-- | 3.2% (6) |

|

| Sociable | 19.7% (15) |

15.0% (17) |

-- | 16.9% (32) |

Components do not add up to 100% because items may be coded for more than one component.

DISCUSSION

Our documents analysis demonstrates the importance of brand identity in tobacco marketing that circumvents strong advertising regulations. Tobacco companies research the values and lifestyles of their target populations, and use them to develop brand identities [2]. PM and RJR marketers intended their lifestyle magazines to help build brand identity and hoped that young adults perceived the brand image [22] in a positive way. PM intended Unlimited to complement the Marlboro brand [43], while RJR intended CML to circumvent possible advertising regulations [73].

Viewing brand imagery is associated with the positive perceptions of brands in adolescents [89] and youth and young adult exposure to smoking images in the media is associated with increased tobacco use or positively identifying with smokers [90, 91].

These positive brand images were viewed by PM and RJR as an important tool in retaining smokers. The lifestyle magazines were designed to create a positive experience with the Marlboro and Camel brands that could last for hours longer than any single cigarette advertisement. By integrating the brand image throughout the magazine, readers are engaged with a brand identity for over 100 pages, rather than a fleeting single exposure as one would expect by placing a tobacco advertisement in a mainstream magazine. In addition, the magazines invite the reader to engage by going online, sending additional copies of the magazine to their friends, redeeming coupons for merchandise, and participating in surveys or contests offered in the magazine.

Unlimited and CML differed in smoking content and brand identity conveyance. Although previous research demonstrates that young men may not be fazed by smoking images in magazines [91], our content analysis suggests that conveying brand identity instead of smoking images may have been one way in which the tobacco industry attempted to influence the many young adults who smoke, but are not yet regular smokers [4, 5], or who quit and relapse more frequently [4]. While there are no data that directly link exposure to these lifestyle magazines and young adult smoking rates, a recently published comprehensive review conducted for the National Cancer Institute concluded “an abundance of evidence from multiple lines of research collectively establishes a causal link between tobacco marketing and smoking behavior” [92].

Unlimited integrated the Marlboro brand identity to subtly remind the reader that it was from their “friends at Marlboro “ [36]. Unlike Unlimited, CML was rife with positive images of smoking, brand logos and less subtle camel images. This suggested that CML promoted smoking directly using positive smoking imagery, rather than conveying positive brand identity. By communicating freedom, independence, and sociability, the tobacco industry-produced lifestyle magazine “is a reminder and reinforcer [to the smoker], while to non-smokers it is a temptation and a teacher of tolerance” [93].

Our documents analysis did not reveal why Unlimited and CML were discontinued or directly point to what replaced them. However, surveillance of tobacco industry marketing shows that while these magazines may no longer be distributed, the Internet is likely the new frontier for tobacco lifestyle marketing.

Brand websites, a relatively new marketing channel, operate in the multimedia-integrated tradition of the lifestyle magazines. Websites can operate as advertising [94], and normalize smoking as a common occurrence. RJR website planning documents emphasized young adult lifestyle content and reinforcing Camel brand identity similar to CML [95]. Surveillance of Camel’s website between 2005 and 2008 shows that it infuses lifestyle elements with brand-sponsored events and other marketing vehicles that are consistent with the core elements of the brand identity [96]. Also, in 2006, the content director for RJR’s event marketing agency for Camel, BFG Communications, stated that their “charter is to create a lifestyle magazine online” [97] with the Camel website.

Such brand websites are not the sole source of Internet tobacco promotion; smoking content can also be found on social networking and video sharing sites such as MySpace, Facebook, and YouTube. Although such content is supposedly consumer-generated it may be that some are in fact posted by the tobacco industry as a form of “covert advertising” [98]. This method of using the Internet is not unfamiliar to the tobacco industry; PM and RJR considered creating Internet content for Unlimited [36] and CML since the late 1990s and early 2000s [88].

CONCLUSION

Clinicians and health professionals need to recognize that lifestyle promotions that lack overt images of smoking may still promote tobacco use by shaping the positive image of tobacco brands. The industry continues to pursue the objectives for lifestyle magazines in other new media.

Readers shared tobacco lifestyle magazines with others [52], and this peer-to-peer activity could increase readership exponentially through recipients’ social networks, and potentially reach non-smokers and youth. The magazines also integrated self-identity and cigarette brand identity. The message to beginning smokers is effectively: To quit tobacco means to quit you.

Traditional definitions of advertising and legislation regulating it fall far short of what is required to limit the marketing activities demonstrated in this paper. These “under the radar” strategies integrating brand identity into editorial content circumvent the spirit of strict advertising regulations found in Article 13 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), and are more likely to be deployed when restrictive tobacco regulations are in place and enforced. For example, the current advertorial campaigns in the US, such as RJR’s Camel “Indie Rock Universe” spread [99], utilize the “under the radar” technique pioneered in CML of “hiding” a tobacco ad by making it look like content. However, if the United States ratified the FCTC and implemented Article 13 as recommended, these “under the radar” approaches would be eliminated[100]. We recommend ratification of the FCTC because of its comprehensiveness in restricting tobacco advertising and including populations in addition to youth.

The tobacco industry has a long history of efforts to link their brands to attractive and aspirational lifestyles, particularly for young people. These efforts include but are not limited to the lifestyle magazines that are the focus of this study. Tobacco companies recognize that lifestyle activities are a powerful medium for connecting with beginning smokers, and clinicians and health professionals should support advertising restrictions and develop counter-marketing strategies appealing to late adolescents and young adults that directly challenge these under the radar efforts to integrate tobacco brand identity with seemingly innocuous young adult lifestyle content. Counter-marketing campaigns that bring to light the specific targeting of young adults may be a successful approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Tim Dewhirst from the University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada and Dr. Ruth Malone and Dr. Libby Smith from the University of California, San Francisco for their assistance with the coding instrument development. We also thank Olivia Wackowski for her assistance with the methods and the tobacco website data.

FUNDING

This work was funded by support from the National Cancer Institute Grants CA-87482, CA- 126433 and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute.

Contributor Information

Daniel K. Cortese, Governors State University, Political & Justice Studies, University Park, Illinois, USA

M. Jane Lewis, University of Medicine and Dentistry, New Jersey, School of Public Health, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

Pamela M. Ling, University of California, San Francisco, Department of General Internal Medicine, San Francisco, California, USA

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2007 4 Jan];Smoking Prevalence among U.S. Adults. 2006 October; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/research_data/adults_prev/prevali.htm.

- 2.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and How the Tobacco Industry Sells Cigarettes to Young Adults: Evidence from Industry Documents. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Research on Smoking Cessation: Recapturing Young Adults and Other Recent Quitters. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biener L, Albers A. Young Adults: Vulnerable New Targets of Tobacco Marketing. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(2):326–330. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Association of Attorneys General. [cited 2007 12 Dec];Master Settlement Agreement. 1998 Available from: http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa.

- 7.Gilpin E, White M, White V, et al. Tobacco Control Successes in California: A Focus on Young People, Results from the California Tobacco Surveys, 1990 – 2002. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilpin E, White V, Pierce J. How Effective are Tobacco Industry Bar and Club Marketing Efforts in Reaching Young Adults? Tobacco Control. 2005;14:186–192. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.'Custom' Magazines Proliferate, but So Do Credibility Questions. Philip Morris; 1994. Feb 14, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bvv72e00. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckley S. Philip Morris; 1994. Jun 15, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cfx26c00. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds RJ. The Camel Magazine. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Camel 1998 (19980000) Direct Marketing. 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/adt97c00. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unlimited Overview. Philip Morris; 1999. Jun 21, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lmg80b00. [Google Scholar]

- 13.900183.XLS. Program Information. Camel Magalog 2. RJ Reynolds; 2000. Jan 21, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cek56a00. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter RB, Barbee MS, Ip LS. CML2 Vs. CML1. RJ Reynolds; 2000. 531278252/531278253. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unlimited. Targeted to Men 21-29. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Nov 17, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wji60d00 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Advertising Age. Magazine circulation for 6 mos. 2001 Feb 19; ending 12/31/00. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Media Newsbriefs Volume 8. Philip Morris; 1999. 2084080694/2084080696. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young T. Creative Brief for Magazine Plan. Philip Morris; 1996. Apr 08, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vli57c00. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malone R, Balbach E. Tobacco Industry Documents: Treasure Trove or Quagmire? Tobacco Control. 2000;9:334–338. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riffe D, Lacy S, Fico FG. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. Oxford, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Human Communication Research. 2002;28(4):587–604. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaker D. Building Strong Brands. New York: The Free Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marlboro's Core Values. Philip Morris; 2002. Jan, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ruh12c00. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marlboro Brand Essence. Philip Morris; 1999. 2083723174/2083723175. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camel Magazine Vision Document. RJ Reynolds; 1997. Jul 31, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uqf46a00. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creighton FV. 1998 (980000) Camel Plan. RJ Reynolds; 1998. 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tln76d00. [Google Scholar]

- 27.RJR Presentation at Cagny Feb 24, 2000. Brown & Williamson; 2000. Mar 01, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rlg21c00 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huyett D, Peoples M. 1998 (19980000) Camel Database Marketing Plan. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Feb 20, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ozz60d00 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Food and Drug Administration. Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco Products to Protect Children and Adolescents; Proposed Rule. [cited 2007 12 Dec];1995 Aug 11;Vol. 60 Number 155:[Available from: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/fr/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Food and Drug Administration. Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents; Final Rule. [cited 2007 12 Dec];1996 Aug 28;Vol. 61 Number 168:[Available from: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/fr/index.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler DA, Witt AM, Barnett PS, et al. The Food and Drug Administration’s Regulation of Tobacco Products. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996 September 26;335(13):988–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barents Group LLC, KPMG Peat Marwick LLP. The Costs of Proposed FDA Regulations Regarding the Advertisement, Labeling and Sale of Tobacco Products. Lorillard; 1995. Dec 19, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tot20e00. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potential Questions on FDA Ruling. Philip Morris; 1995. Jun, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pts75c00. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Food and Drug Administration, et al. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. et al.: United States Supreme Court, 2000:U.S. 120.

- 35.Morris Philip. Untitled. Philip Morris; 2000. 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsk27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund N. Unlimited - Action, Adventure and Good Times Unlimited Magazine 20010000 Plan. Philip Morris; 2000. Aug 25, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kwj27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris P. Unlimited - Background. Philip Morris; 2002. Jan, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/noj27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valente VP. Philip Morris; 1994. Sep 26, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kkd37c00. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hachette Filipacchi Magazines, Philip Morris. Agreement. Philip Morris; 1996. May 15, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tyu94c00. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris Philip. Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. Untitled. Philip Morris; 1998. Sep 09, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qwz73c00. [Google Scholar]

- 41.N344. Philip Morris; 1995. Dec, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/asf57d00. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manrique M. Unlimited Magazine Story Approval. Philip Morris; 1999. Nov 12, Philip Morris USA. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fxj86c00. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unlimited Action, Adventure, Good Times General Questions. Philip Morris; 1995. Dec, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dsf57d00. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomasik S. Proposed Unlimited Media Kit Research Changes. Philip Morris; 1999. Apr 21, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bzb48c00. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Untitled. Philip Morris; 1999. Mar 25, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xyb48c00. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unlimited Hachette Meeting Agenda Friday, 990716 10:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Philip Morris; 1999. Jul 16, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vkq75c00. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unlimited Action, Adventure, Good Times. Philip Morris; 1999. 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/njb90b00. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris Philip. Editorial Highlights. Philip Morris; 1996. Jun, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/juf47d00. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Starcom Media Services. Unlimited Advertiser Analysis Three-Year Trend (960000, 970000, 980000) Philip Morris; 1999. Jun 28, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fzb48c00. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Looking Glass Group. Qualitative Research Report New Magazine Concept Focus Groups Conducted 950320 & 950321, 950418 & 950419 and 950620 & 950621. Philip Morris; 1995. Jun 30, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vfk18d00. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohli U, Philip Morris. Unlimited Magazine Focus Groups. Philip Morris; 1995. Aug 22, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ufk18d00. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unlimited Reader Survey Fall 980000 Issue. Philip Morris; 1998. Nov, Beta Research, Hachette Filipacchi Magazines Beta Research, Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eup10c00. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCole D. Unlimited Magazine Research. Philip Morris; 1999. Jun 18, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tjk27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Essery M. Unlimited Reader Survey - Fall 20000000 Issue. Philip Morris; 2000. Dec 01, Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iqw12c00. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marryshow KS. Unlimited Reader Survey. Philip Morris; 2001. Nov 11, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wdi12c00. [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Connor JM. Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. Philip Morris; 2001. Nov 29, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lqw12c00. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marlboro Unlimited Magazine Telephone Research - Final Report. Philip Morris; 1999. Jun, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/oqj87a00. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unlimited Reader Survey Comparison. Philip Morris; 1998. 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dup10c00. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hachette Filipacchi Magazines, Philip Morris. Untitled. Philip Morris; 1995. Sep 27, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nzu94c00. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eisen K, Wood M. Weekly Highlights. Philip Morris; 1995. Jun 19, Philip Morris USA. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jgs75c00. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Untitled. Philip Morris; 1995. Apr 21, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mkd37c00. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kohli U. Unlimited Magazine Female Focus Groups. Philip Morris; 1995. Oct 02, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tfk18d00. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Unlimited Magazine a New, Exciting Marketing Vehicle for Marlboro. Philip Morris; 1996. Sep 01, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nbj59a00. [Google Scholar]

- 64.H+W, Information Source Intl., Philip Morris Marlboro Unlimited Magazine Telephone Research. Philip Morris; 1999. Apr 15, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bcx94a00. [Google Scholar]

- 65.20000000 Plans Presented to Geoffrey C. Bible. Philip Morris; 1999. Nov 30, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rsj27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Untitled. Philip Morris; 1998. Sep, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vle37c00. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Primary Records for Unlimited.Doc. Philip Morris; 2001. Dec 18, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mxc18c00. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomasik S. Recap of Unlimited Media Contributions. Philip Morris; 1999. Mar 29, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ezb48c00. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brainstorming Questions. Philip Morris; 2002. Jan, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/quh12c00. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brain-Storming Session. Philip Morris; 2002. Jan 29, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ooj27a00. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kelly KJ. Philip Morris Snuffs Out Mag. New York Post. 2004 Nov 10; Sect. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Agenda for Camel Cash Brainstorming Meeting - Friday 10am -4. RJ Reynolds; 1997. May 12, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iuf61d00. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Our Mag.Doc. Rationale. RJ Reynolds; 1996. Mar 19, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fxq97c00. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuruc G. RJR. 1998 (19980000) Planning Meeting. RJ Reynolds; 1997. Sep, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hwi97c00. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ittermann PF. Magazine Project. RJ Reynolds; 1997. Sep 05, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qap36a00. [Google Scholar]

- 76.This is in Regard to Next Steps on the Camel Magazine Project. RJ Reynolds; 1997. Sep 12, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ddq80d00. [Google Scholar]

- 77.This is in Regard to Next Steps on the Camel Magazine Project. RJ Reynolds; 1997. Sep 12, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pcf56d00. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Next Steps. Each Brand Develop Framework for Exploring Custom Publication. RJ Reynolds; 1996. Dec, 00 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hxq97c00. [Google Scholar]

- 79.McAtee EM. PM Unlimited Magazine/Holiday Bonus. RJ Reynolds; 1996. Dec 03, Marlboro. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ijv90d00. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ittermann PF, Gray R. Marlboro Unlimited-Fall 1998 (19980000) RJ Reynolds; 1998. Oct 01, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lcf08c00. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ittermann PF, Gray R. Magazine Title. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Mar 27, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eif46a00. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burwell MB. Thank You So Much for Coming Down to Zipper to the Camel Team. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Jan 26, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qhh82a00. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huyett A. Camel Conversion - Brainstorming. RJ Reynolds; 1998. May 06, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wwf33a00. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Etzel EC, Ittermann PF. Zipper Qualitative Research. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Feb 23, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sdr82a00. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Knouse PF., Jr . Camel Magazine Focus Groups: Cincinnati. RJ Reynolds; 1998. Apr 27, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lmw97c00. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barbee M. CML Articles for Up-Coming Issues. RJ Reynolds; 1999. Sep 23, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hxp36a00. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crosslin CS. General Statement/QA. RJ Reynolds; 1999. Nov 1, Launch of CML Quarterly-Exotic Blends. (19991101). 01 Nov 1999. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ovn46a00. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henson JC, Barbee MS, Brule TRJR. Time Magalog. RJ Reynolds; 1999. Jul 22, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zba15a00. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Donovan RJ, Jancey J, Jones S. Tobacco point of sale advertising increases positive brand user imagery. Tobacco Control. 2002 Sep;11:191–194. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Song AV, Ling PM, Neilands TB, et al. Smoking in Movies and Increased Smoking among Young Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2007. 2007 Nov;33(5):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carter OBJ, Donovan RJ, Weller NM, et al. Impact of Smoking Images in Magazines on the Smoking Attitudes and Intentions of Youth: An Experimental Investigation. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:368–372. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Washington DC: United States National Institutes on Health; 2008. Aug, Influence of Tobacco Marketing on Smoking Behavior; pp. 211–291. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:136–147. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anderson SJ, Ling PM. And they told two friends, and so on, and so on: R J Reynolds’ viral marketing of Eclipse. Tobacco Control. 2008 doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.024273. Epub(March 2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simmons M. Internet Strategic Direction. RJ Reynolds; 2000. Feb 17, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/plf56a00. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lewis M, Wackowski O. American Public Health Association. Washington, DC: 2007. Nov 3 – 7, Tobacco Industry Brand Websites and Industry Strategies. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 97.BFG Communications. [cited 2008 4 April];Camel Focuses on Events. 2006 Available from: http://blog.bfgcom.com/?page_id=22.

- 98.Freeman B, Chapman S. Is “YouTube” telling or selling you something? Tobacco content on the YouTube video-sharing website. Tobacco Control. 2007:207–210. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reynolds RJ. Indie Rock Universe. Rolling Stone. 2007 November 15; [Google Scholar]

- 100.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2005