Abstract

Objective

To test the viability of the Mediterranean diet as an affordable low-energy-density model for dietary change.

Design

Foods characteristic of the Mediterranean diet were identified using previously published criteria. For these foods, energy density (kJ/100 g) and nutrient density in relation to both energy ($/MJ) and nutrient cost were examined.

Results

Some nutrient-rich low-energy-density foods associated with the Mediterranean diet were expensive, however, others that also fit within the Mediterranean dietary pattern were not.

Conclusions

The Mediterranean diet provides a socially acceptable framework for the inclusion of grains, pulses, legumes, nuts, vegetables and both fresh and dried fruit into a nutrient-rich everyday diet. The precise balance between good nutrition, affordability and acceptable social norms is an area that deserves further study. The new Mediterranean diet can be a valuable tool in helping to stem the global obesity epidemic.

Key words or phrases: Mediterranean diet, diet quality, food prices, diet cost, nutrient density, energy density, obesity

Rising rates of obesity worldwide have been linked to the growing consumption of energy-dense foods, many of which are increasingly nutrient poor1. Refined grains, added sugars, and added fats have become the staple foods of industrialized nations2. Developing nations undergoing nutrition transition also replace the traditional plant-based diets with more simple sugars and more added fats3. Such energy-dense foods, high in fats, sugars and sodium, have the advantage of being good-tasting, affordable, and convenient. Providing dietary energy at very low cost, they are preferentially consumed by lower income groups. The new diets tend to be energy-dense, supplying more energy, but fewer nutrients per gram4.

The Mediterranean countries have not been spared by such dietary trends. Longitudinal analyses show that the diet of the Mediterranean nations has become much higher in both sugar and fat and more homogeneous than it was in the 1960’s5. Children’s body weight and health may have been adversely affected: data from the International Obesity Taskforce (IOTF) show that childhood obesity rates were higher in Mediterranean countries as compared to northern Europe6.

One might ask what happened to the Mediterranean diet and its protective effects on health. The traditional Mediterranean diet was rich in grains, plant foods, and fish, with limited amounts of red meat. However, foods that were once inexpensive now cost much more. The Mediterranean diet has come to be viewed, at times, as a high-cost option for the elite, especially when transplanted from its rustic roots to an urban North American setting7. Yet it might become a potential cultural model for low-energy-density diets everywhere.

The present analyses explored the interrelations between energy density, nutrient density and the energy cost of foods and food groups said to be characteristic of the Mediterranean diet. The goal was to resolve a common dilemma. Foods with most nutrients and least energy tend to be the most expensive, at least on a per unit of energy (MJ, kcal) basis. As food prices rise (or the food budget shrinks), the first items dropped from the diet are the most costly and most healthful options: high quality proteins, meat and fish, vegetables and fruit. Energy-dense refined grains, sugars and fat remain to fill hungry stomachs8,9.

Lower cost, yet nutritious options are rarely considered, partly because their use can violate social norms. With a few exceptions, pulses, legumes, nuts, dried fruit and canned fish are not a part of mainstream American diet. By contrast, they can be easily incorporated within a Mediterranean eating pattern. The Mediterranean diet provides a ready-made mechanism to include many such low-cost yet nutritious foods within a perfectly acceptable social and gastronomic framework. High-quality nutrition and high social acceptability might be the two advantages of the new Mediterranean diet.

What is the Mediterranean diet?

In 2003, Trichopoulou et al. described a diet scoring system that measured the degree of adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet10. Based on dietary data collected using food frequency questionnaires, individual diets received one point if their consumption of specific foods or food groups was above the population median. No points were awarded if consumption fell below the median. Based on previous research, the following foods, food groups and nutrients were said to be the essence of the traditional Mediterranean diet: vegetables (excluding potatoes), legumes, fruits, nuts, seeds, cereals, fish, ratio of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) to saturated fatty acids (SFA), and moderate alcohol consumption (in the 5 – 50 gram range).

Similarly, foods considered detrimental to health were also scored according to whether the individual consumption was above (0 points) or below the median (1 point). Foods in the latter category included meat, poultry, and dairy products. Finally, scores for beneficial and detrimental food classifications were added together for a final score, ranging from 0 to 9. Higher scores, indicating higher adherence to a traditional Mediterranean diet were associated with lower total mortality rates and with reduced death due to cancer or coronary heart disease10–12.

A few months later, Goulet, et al. suggested a North American version of the Mediterranean diet13. The beneficial foods in the Mediterranean diet were identified as vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, whole grain cereals, poultry, fish, canola and olive oils, and low-fat dairy products. Foods antithetical to the Mediterranean regime were identified as red meat, refined grains, sweets and desserts, fast foods, and (whole/full fat) dairy products13. These principles are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Comparison of Mediterranean diet scoring as described by by Trichopoulou, et al. and Goulet, et al.

| Food Group | Greek Mediterranean Diet Score developed by Trichopoulou, et al.10 | Canadian Mediterranean Diet Score developed by Goulet, et al.13 |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median (Excluding potatoes) |

0 = Less than 1 serving daily 1 = 1 serving daily 2 = 2 servings daily 3 = 3 servings daily 4 = 4 or more servings daily |

| Legumes | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

0 = Less than 0.5 servings daily 1 = 0.5 servings daily 2 = 1 serving daily 3 = 2 servings daily 4 = 3 or more servings daily |

| Nuts and seeds | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

0 = Less than 0.5 servings daily 1 = 0.5 servings daily 2 = 1 serving daily 3 = 2 servings daily 4 = 3 or more servings daily |

| Fruits | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

0 = Less than 1 serving daily 1 = 1 serving daily 2 = 2 servings daily 3 = 3 servings daily 4 = 4 or more servings daily (Maximum of 1 point for fruit juice) |

| Cereals | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

0 = Less than 1 serving daily 1 = 1 – 2 servings daily 2 = 3 – 4 servings daily 3 = 5 – 6 servings daily 4 = 7 or more servings daily (Maximum of 1 point for refined grains) |

| Fish | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

0 = None/Never 1 = Less than 1 serving weekly 2 = 1 serving weekly 3 = 2 servings weekly 4 = 3 or more servings weekly (Non-breaded only) |

| MUFA/Saturated fat ratio | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = Intake greater than median |

|

| Olive oil or olives | 0 = Less than 1 serving daily 1 = 1 serving daily 2 = 2 servings daily 3 = 3 servings daily 4 = 4 or more servings daily |

|

| Canola oil or olive oil margarine | 0 = Less than 1 serving daily 1 = 1 or more servings daily |

|

| Alcohol | 0 = Intake less than median 1 = (Men) Intake 10 – 50 g daily 1 = (Women) Intake 5 – 25 g daily |

|

| Meat | 0 = Intake greater than median 1 = Intake less than median |

0 = 7 or more servings weekly 1 = 5 – 6 servings weekly 2 = 3 – 4 servings weekly 3 = 1 – 2 servings weekly 4 = Less than 1 serving weekly (Red meats or processed meats) |

| Poultry | 0 = Intake greater than median 1 = Intake less than median |

0 = None/Never 1 = 1 serving weekly, OR 4 or more servings weekly 2 = 2 servings weekly 3 = 2 servings weekly 4 = 3 servings weekly (Non-breaded only) |

| Dairy Products | 0 = Intake greater than median 1 = Intake less than median |

0 = Less than 1 serving daily, OR More than 4 servings daily 1 = 4 servings daily 2 = Not scored 3 = 1 serving daily 4 = 2 – 3 servings daily |

| Eggs | 0 = 7 or more servings weekly 1 = Not scored 2 = 5 – 6 servings weekly 3 = Not scored 4 = 0 – 4 servings weekly |

|

| Sweets and desserts | 0 = 7 or more servings weekly 1 = 5 – 6 servings weekly 2 = 3 – 4 servings weekly 3 = 1 – 2 servings weekly 4 = Less than 1 serving weekly |

Is the Mediterranean diet low-energy-density?

Energy density of foods, defined as available joules (or calories) per unit weight (kJ/100 g, or kcal/100g), is largely a function of the foods’ water content14. Because water provides weight but no energy, it contributes more to the energy density of foods than does any macronutrient, fat included. Together, water and fat account for over 95% of the variance in the energy density of the food supply; sugars, starches and fiber play a relatively minor role.

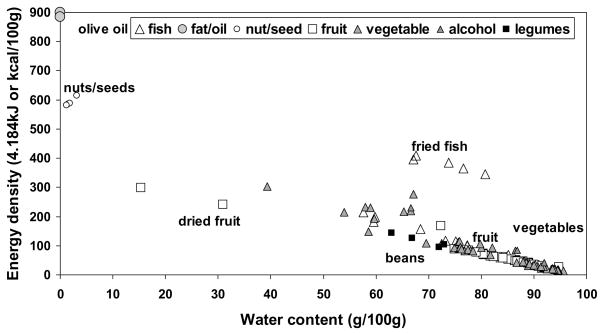

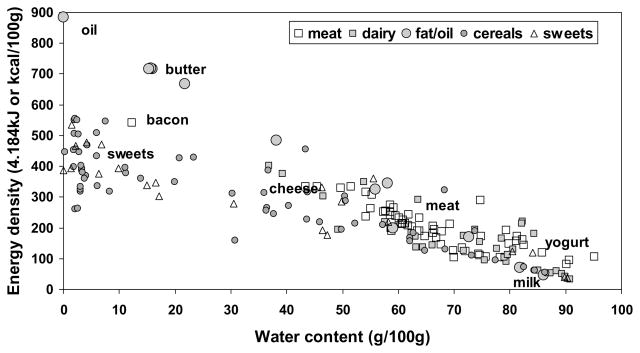

Energy density of key foods and food groups in the Mediterranean diet was assessed using nutrient composition databases provided by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). Figures 1 and 2 show an inverse relationship between the foods’ water content and their energy density. Fruits and vegetables contain very high amounts of water (wt/wt); fruits generally contain 75–85g of water per 100g weight, whereas vegetables can contain as much as 85–95g and have a slightly lower energy density compared to fruits. Dry grains and cereals were energy dense, whereas vegetables and fruit had energy density below 0.21 MJ/100g (50 kcal/100g). Dried fruits contained <30g water per 100g and had higher energy density. Beans and legumes were moderately high in water content (65g/100g) and relatively low in energy density.

Figure 1.

The relation between energy density and water content in foods (fish, fat/oil, nut/seed, fruit, vegetable, alcohol, legumes)

Figure 2.

The relation between energy density and water content in foods (meat, dairy, fat/oil, cereals, sweets)

Yogurt and low-fat milk were low energy density foods containing 80–85g water per 100g. Their energy density was in the range of 0.3 – 0.5 MJ/100g (75–125 kcal/100g). Energy density of cheeses (40g water/100g), was 1.5 MJ/100g (350 kcal/100g). Energy density of fried fish (65–70% water) was 1.7 MJ/100g (400 kcal/100g).

Dry grains (5–15g water/100g), nuts and seeds (<5g water/100g) had higher energy density. Oils, including olive oil, had the highest energy density (3.8 MJ/100g, or 900 kcal/100g). The energy density of mixed dishes, such as pizza, stews or soups depended on their moisture and water content

Do Mediterranean foods cost more per 100 grams?

Food price data for the key foods in the Mediterranean diet were gathered in 3 principal Seattle supermarkets in 2006. Exploring the relation between energy density and food cost per 100g revealed a wide variation both within and across food groups. For example, the price of fresh fruit varied widely from $0.05–0.10 per 100g to as much as $3.00–5.00 per 100g. Most vegetables clustered around $0.75/100g, although some fresh salad greens cost up to $2.00 or more per 100g.

The 2003 USDA report suggesting that Americans could obtain 7 servings (0.5 cup or 50 gram serving size) of fresh vegetables and fruit for as little as 64 cents seems to have little basis in reality15, unless the cheapest options were to be used exclusively every day. The USDA’s 2005 My Pyramid avoided recommending numbers of servings daily in favor of recommending total volume consumption16. However, if one applies their previous standard serving size to the 2005 recommendations (2 servings of fruits and 3 servings of vegetables)16, daily costs could reach several dollars per day.

By contrast, legumes were low energy density and low cost foods. Their cost per 100 grams was generally between $0.50 – 0.75, while their energy density ranged between 0.4–0.8 MJ/100g (100–200 kcal/100g). Cereal prices clustered mostly between $0.50 – 1.00/100g, although some were very inexpensive ($0.05/100g). Nuts and seeds had high energy density, around 2.5 MJ/100g (600 kcal/100g) and cost approximately $1.00/100g.

Do Mediterranean foods cost more per MJ?

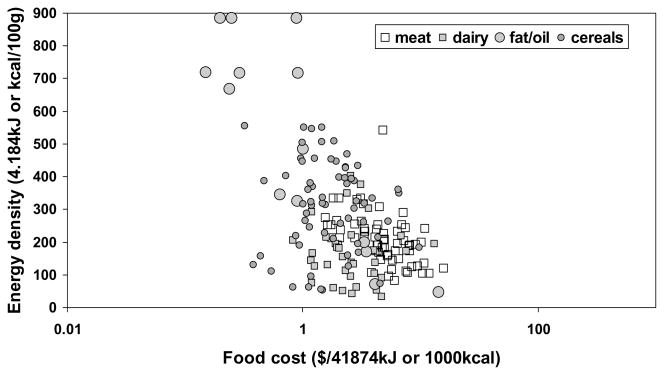

Budget constraints often determine diet composition, since some foods provide more energy per unit price than do other foods. Generally consumers need to obtain the daily energy ration of 8.4–10.5 MJ (2,000–2,500 kcal) at a given price. The Seattle food prices, initially calculated per 100g, were therefore adjusted for energy by dividing by energy density of foods. Figure 3 shows energy density plotted against energy cost.

Figure 3.

The relation between energy density and food cost (meat, dairy, fat/oil, cereals)

The low-energy density fruits and vegetables, including berries, melons, salad and leafy greens, were associated with the highest per calorie energy costs. Meat, and especially fresh fish were relatively expensive, again on a per calorie basis. In contrast, dairy products, an alternative protein source, offered low energy density at moderate cost; most dairy products clustered around 0.4 MJ/100g. The overall energy cost for dairy products tended to be lower than for meat or fish. Among vegetables, the less expensive root vegetables such as carrots or potatoes tended to be more energy dense. Legumes represent an important protein source, while offering relatively low energy density at a relatively low cost ($1.00 – 25.00 per 4.18 MJ, or $1.00 – 25.00 per 1000 kcal).

Cereals generally cost less than meats, yet more than fats and oils. Their energy density varied roughly ten-fold, from 0.2 MJ/100g (50 kcal/100g) for oatmeal to 2.0 MJ/100g (500 kcal/100g) for granola bars with nuts and seeds. Generally, nuts and seeds cost between $1.00 – 25.00 per 4.18 MJ (1000 kcal), in part due to their relatively high energy density.

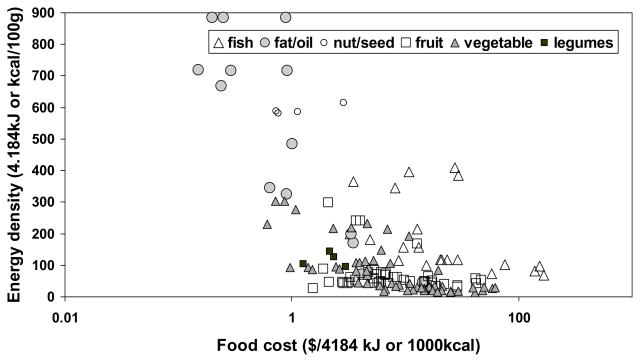

Figure 4 reinforces the point that Mediterranean-style foods can be obtained at all price ranges, whether calculated per 100g or per 4.18 MJ (1000 kcal). The only proviso is that the new Mediterranean diet needs to include more grains, legumes, nuts, vegetables and fruit and less leafy greens and fresh fish. Doing so allows re-creation of the Mediterranean eating pattern at an affordable cost.

Figure 4.

The relation between energy density and food cost (fish, fat/oil, nut/seed, fruit, vegetable, legumes)

Are Mediterranean foods nutrient-rich?

The notion of dietary energy per unit cost needs to be supplemented with the notion of nutrients per unit cost. The question of whether Mediterranean foods are nutrient-rich can be answered using nutrient profiling, a quantitative method used to assess the nutrient quality of individual foods17–19.

Each food’s nutrient adequacy score can be calculated based on the nutrients the food contains relative to its provided dietary energy9,17. The nutrient adequacy score (NAS) is based on percent daily value (DV) for N key nutrients as provided by 100g of food. Mathematically, this is represented as:

A food’s nutrient density score (NDS) is based on percent DV as provided by 0.4 MJ (100 kcal) of food:

where ED represents energy density.

Finally, a nutrient-to-price ratio (NPR) may be computed for each food using the expression:

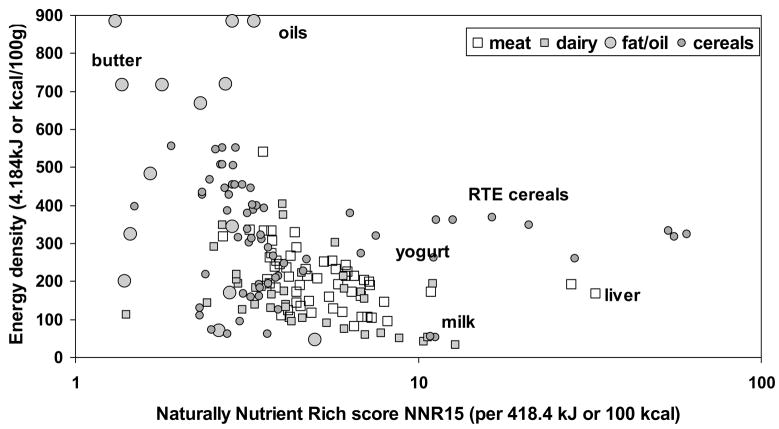

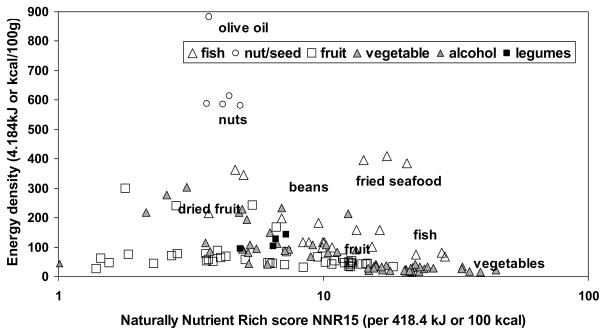

The present analyses used the Naturally Nutrient Rich index17 to assess the nutrient quality of individual foods typical of the Mediterranean diet. The NNR index was based on 15 beneficial nutrients, including protein, fiber, monounsaturated fatty acids, and a range of vitamins and minerals. Figures 5 and 6 show the relationship between NNR scores and the foods’ energy density.

Figure 5.

The relation between energy density and nutrient density in foods (meat, dairy, fat/oil, cereals)

Figure 6.

The relation between energy density and nutrient density in foods (fish, nut/seed, fruit, vegetable, alcohol, legumes)

The low energy density foods were also most likely to be nutrient rich. Vegetables scored uniformly high. Most of the high scoring vegetables had low energy densities. With the exception of dried fruit, the energy density of most fruit was low, with relatively high corresponding nutrient densities. Beans and legumes also had relatively high NNR scores.

Higher nutrient density scores were obtained for fish, both fresh and fried, organ meats and lean red meat than for processed meats and for high fat cuts of meat. Dairy products showed a range of nutrient density scores, with highest scores obtained from low fat yogurts and other low fat dairy products. Some dry cheeses containing saturated fats and sodium tended to score less well. Additional NNR 15 scores are presented for cereals, nuts and seeds, oils and alcoholic beverages. Sweets and desserts represented poor nutritional value expressed as nutrients per unit cost.

As might be expected given the inverse relation between energy density and energy cost, there was a positive relation between nutrient density and energy cost. However, not all nutrient rich foods necessarily cost more. Among the more expensive foods were fish and shellfish, fruit, some vegetables, some cheeses, and some nuts. Among the lower cost foods were other vegetables, beans and other legumes, grains, nuts and some dairy products. It should be possible to construct a Mediterranean style diet using the lower cost options in every category.

Can the Mediterranean diet halt the obesity epidemic?

Diets high in refined grains, added sugars, and added fats are both good tasting and affordable. Although inexpensive, such diets are energy dense and nutrient poor. The current emphasis is on replacing refined grains, fast foods, desserts added sugars and added fats with more whole grains, lean meats, fish, and fresh vegetables and fruit. However, such diets, although palatable and nutritious, are usually associated with higher costs per MJ and per day.

Goulet, et al. found that promoting a Mediterranean dietary pattern need not necessarily be associated with higher overall dietary costs20. The key to avoiding increased overall dietary costs lies in educating consumers about lower cost foods while selectively purchasing limited amounts of higher cost ones.

In controlled clinical trials, variations of the Mediterranean diet have demonstrated efficacy for both weight loss and improving glycemic measures in diabetics. Shai, et al. recently reported on a two-year intervention study in which those individuals assigned to an energy-restricted Mediterranean diet lost more weight initially and gained less back over time in comparison to those assigned to an energy-restricted low-fat diet21. For female participants, the Mediterranean diet proved even more efficacious for weight loss. The diabetic subjects assigned to the Mediterranean diet group experienced greater improvements in fasting plasma glucose and insulin21.

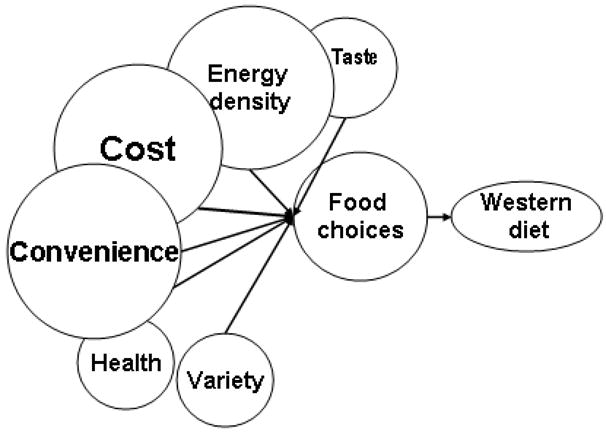

Attempts to steer Western consumers toward lower cost yet nutrient dense foods have encountered resistance. Many diets composed of mostly plant foods with meat used only as a condiment; vegan-style diets, or diets based exclusively on rice and beans are outside the American or European mainstream. Consumers generally resist eating less-familiar foods; particularly if they believe that doing so means abandoning their cultural heritage, or that those foods are associated with people of different culture or different social class. People prefer eating within their own food culture, such that any recommended diet must meet the triple test of nutrition, cost, and social norms (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The elements of consumer food choice (Western diet)

The multiple challenges involved in improving diet quality include helping people recognize the lower cost foods within their cultural heritage, reducing any stigma attached to (other) low cost foods, increasing the convenience and accessibility of lower cost, lower energy density foods, and finally, doing so without sacrificing taste or enjoyment.

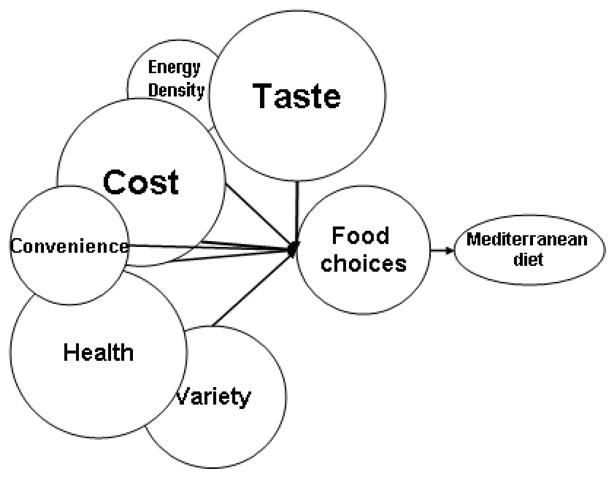

The barriers are not insurmountable. The Mediterranean diet, recently described as the cultural heritage of all mankind, offers a way to incorporate nutritious yet lower cost foods within a coherent gastronomic structure. Many cultures around the world feature plant-based dishes that include small amount of meats, and incorporate legumes, grains, and other nutritious lower cost foods. The Mediterranean diet provides a viable cultural framework to incorporate low cost yet nutritious foods into the diet, notably pasta and beans, vegetables (tomatoes, eggplant), oil, wine, dried fruit, nuts and seeds.

Allowing consumers to explore their shared cultural food heritage through culinary education might represent a first step. Adapting the traditional food preparation techniques to the modern world would help promote the Mediterranean diet. As with dried legumes, preparation techniques can facilitate convenience of preparing foods made using whole, unprocessed grains. Low- or nonfat dairy products and eggs represent less expensive protein sources. Fermented dairy products such as yogurt or kefir are traditional in the Mediterranean region. Pasta, grains and beans can help replace the more expensive meats and fresh fish. Mixed dishes featuring combinations of meat and plant based foods are one staple of the Mediterranean diet. Replacing added sugars and fats with dried fruits, nuts and oils could enhance taste while providing increased nutrient value.

The combination of high enjoyment, low cost and good nutrition can be a powerful tool against the obesity epidemic (see Figure 8). The Mediterranean diet, whether the traditional or the North American modified version, provides a social and gastronomic framework that need not be associated with higher diet costs.

Figure 8.

The elements of consumer food choice (Mediterranean diet)

Acknowledgments

AD supported by USDA grant 2004-35215-1441, PE supported by NCCAM grant 2 T32AT000815. The authors’ contributions were as follows: AD performed the data analysis, and both authors participated in writing the manuscript. There were no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The publisher’s final edited version of this article is available at Public Health Nutr.

Presentation at VII Barcelona International Congress on the Mediterranean Diet, Barcelona, March 11 – 12, 2008

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Technical Report Series no. 916. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Available at http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment: Dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: New trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewnowski A, Darmon N. The economics of obesity: Dietary energy density and energy cost. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(Suppl 1):265S–273S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.265S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidhuber J. The changing structure of diets in the European Union in relation to healthy eating guidelines. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:584–595. doi: 10.1079/phn2005844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. IASO International Obesity TaskForce. Obesity in children and young people: A crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(Suppl 4–104):20–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crotty P. The Mediterranean diet as a food guide: The problem of culture and history. Nutr Today. 1998;33:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan M. Statement at the high-level conference on world food security. Rome: WHO; 2008. Available at http://www.fao.org/foodclimate/conference/statements/day1-pm/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrieu E, Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Low-cost diets: More energy, fewer nutrients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:434–436. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. NEJM. 2003;348:2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitrou PN, Kipnis V, Thiébaut ACM, Reedy J, Subar AF, Wirfält E, Flood A, Mouw T, Hollenbeck AR, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prediction of all-cause mortality in a US population. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2461–2468. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai J, Miller AH, Bremner JD, Goldberg J, Jones L, Shallenberger L, Buckham R, Murrah NV, Veledar E, Wilson PW, Vaccarino V. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is inversely, associated with circulating interleukin-6 among middle-aged men: A twin study. Circulation. 2008;117:169–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulet J, Lamarche B, Nadeau G, Lemieux S. Effect of a nutritional intervention promoting the Mediterranean food pattern on plasma lipids, lipoproteins and body weight in healthy French-Canadian women. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drewnowski A. Energy density, palatability, and satiety: Implications for weight control. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed J, Frazão E, Itskowitz R. How much do Americans pay for fruits and vegetables? United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture information bulletin no. 790. 2004 Available at www.ers.usda.gov.

- 16.United States Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Food Guide Pyramid “Inside the Pyramid”. 2005 Available at http://www.mypyramid.gov/pyramid/index.html.

- 17.Drewnowski A. Concept of a nutritious food: Toward a nutrient density score. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:721–32. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maillot M, Darmon N, Darmon M, Lafay L, Drewnowski A. Nutrient-dense food groups have high energy costs: An econometric approach to nutrient profiling. J Nutr. 2007;137:1815–1820. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drewnowski A, Monsivais P, Maillot M, Darmon N. Low-energy-density diets are associated with higher diet quality and higher diet costs in French adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulet J, Lamarche B, Lemieux S. A nutritional intervention promoting a Mediterranean food pattern does not affect total daily energy cost in North American women in free-living conditions. J Nutr. 2008;138:54–59. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, Golan R, Fraser D, Bolotin A, Vardi H, Tangi-Rozental O, Zuk-Ramot R, Sarusi B, Brickner D, Schwartz Z, Sheiner E, Marko R, Katorza E, Thiery J, Fiedler GM, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Stampfer MJ. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]