Abstract

In human intestinal smooth muscle cells, endogenous insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) regulates growth and IGF-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) expression. The effects of IGF-I are facilitated by IGFBP-5. We previously showed that IGFBP-5 acts independently of IGF-I in human intestinal muscle to stimulate proliferation and upregulate IGF-I production by activation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK. Thus a positive feedback loop exists between IGF-I and IGFBP-5, whereby both stimulate muscle growth and production of the other factor. In Crohn's disease, IGF-I and IGFBP-5 expression are increased and contribute to stricture formation through this effect on muscle growth. To determine the signaling pathways coupling IGFBP-5 to MAPK activation and growth, smooth muscle cells were isolated from muscularis propria of human intestine and placed into primary culture. Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK activation and type I collagen production were measured by immunoblot. Proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Activation of specific G proteins was measured by ELISA. AG1024, an IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was used to isolate the IGF-I-independent effects of IGFBP-5. IGFBP-5-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK and proliferation were abolished by pertussis toxin, implying the participation of Gi. IGFBP-5 specifically activated Gi3 but not other G proteins. Transfection of an inhibitory Gαi minigene specifically inhibited MAPK activation, proliferation, and both collagen-I and IGF-I production. Our results indicate that endogenous IGFBP-5 activates Gi3 and regulates smooth muscle growth, IGF-I production, and collagen production via the α-subunit of Gi3, independently of IGF-I, in normal human intestinal muscle cells.

Keywords: smooth muscle cell, heterotrimeric G protein, p38 MAPK, Erk1/2

the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system plays a crucial role in regulating cellular development, growth and apoptosis. The IGF system is composed of three ligands, namely IGF-I, IGF-II, and insulin, and three receptors, namely IGF-IR, IGF-IIR, and the insulin receptor. IGF-I regulates cell growth by preferential activation of the cognate IGF-IR and is an essential regulator of postnatal cellular proliferation, survival, and transformation. Whereas deletion of the IGF-I or IGF-IR genes results in perinatal death or severe growth retardation, in animals with hepatic-targeted deletion of IGF-I, there is essentially normal growth and development of smooth muscle, including the intestinal muscularis propria (6, 33). Conversely, overexpression of IGF-I results in smooth muscle hyperplasia, including the intestinal muscularis propria (30). This observation emphasizes both the important and sufficient role of autocrine IGF-I production in the regulation of intestinal smooth muscle growth.

IGF-binding proteins, IGFBP-1 to 6, are a highly conserved family of proteins produced in the liver that transport IGFs in the serum. IGFBPs are also produced by nonliver tissues, where they act in autocrine and paracrine fashions to modulate the responses to IGFs. Human intestinal smooth muscle cells produce IGFBP-3, IGFBP-4, and IGFBP-5 that modulate the interaction of IGF-I and IGF-II with IGF receptors by virtue of the higher affinity of IGF- I and IGF-II for the binding proteins than for their cognate receptors. In human intestinal muscle, IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-4 inhibit the interaction of IGF-I with the IGF-IR, whereas IGFBP-5 facilitates the interaction of IGF-I with the IGF-IR (5).

A unique feature of IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and IGFBP-5 is their ability to exert IGF-independent effects on cell growth and survival. These effects are mediated by their ability to either bind to distinct cell surface receptors or undergo nuclear translocation (2, 7, 10, 18). IGFBP-1 interacts with the α5β1 integrin (10), and IGFBP-3 interacts with various TGF-β receptors including type V TGF-β receptors in T47D breast cancer cells and mink lung epithelial cells and with TGF-βRI/II receptors in human intestinal smooth muscle (7, 17). An IGFBP-5-specific receptor has been identified in human intestinal smooth muscle cells, mouse osteoblasts, and rat kidney mesangial cells (1, 18). IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 also possess nuclear localization sequences that mediate β-importin-dependent translocation to the nucleus (25). Their binding to members of the nuclear receptor superfamily including the retinoid receptors, retinoid X receptor (RXR)α, retinoic acid receptor, and vitamin D receptor, where IGFBP-3 regulates apoptosis and IGFBP-5 regulation of osteoblast function has been documented (3, 19, 24, 26).

IGFBP-5 binds to an ∼420-kDa plasma membrane-bound receptor protein and elicits autophosphorylation of serine residues within this protein (2). Although this putative receptor has not yet been cloned and sequenced, signaling pathways coupled to protein autophosphorylation have been identified including IGFBP-5-dependent activation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK that jointly stimulate proliferation and production of IGF-I in human intestinal smooth muscle cells and activation of the small G protein, Cdc42, which stimulates filopodia formation in mesangial cells (4, 18).

The present article shows that IGFBP-5 activates a pertussis toxin (PTx)-sensitive heterotrimeric G protein, Gi3, in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. The Gαi3 subunit derived from Gi3 activation is coupled to IGF-I-independent, IGFBP-5-stimulated activation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK, stimulation of muscle cell growth, and increased production of both type I collagen and IGF-I in human intestinal smooth muscle cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of intestinal muscle cells from human intestine.

Segments of normal intestine were obtained from patients undergoing surgery for nonmalignant disease according to a protocol approved by the VCU Institutional Review Board. Muscle cells were isolated from the circular muscle layer of human intestine using previously reported techniques (11, 12, 15, 18). Muscle cells isolated by enzymatic digestion were placed into primary cell culture. Epithelial cells, endothelial cells, neurons, and interstitial cells of Cajal are not detected in cells isolated and cultured in this fashion (29). We have previously shown that these cells retain their smooth muscle phenotype: immunostaining for smooth muscle markers, expression of γ-enteric actin, and the physiological contractile characteristics of intestinal smooth muscle (29).

Preparation of whole cell lysates.

Cell lysates were prepared as described previously in an immunoprecipitation buffer consisting of (in mM): 50 Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 150 NaCl, 50 NaF, 1 Na orthovanadate, 1 dithiothreitol, 1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5% NP-40 to which was added 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin (15, 16, 18). The resulting lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C before use for immunoblot analysis.

Identification of IGFBP-5-activated G proteins.

Activation of specific G proteins was determined from IGFBP-5-induced increase in Gα binding to guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) as described previously (16, 21). Cells were homogenized in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4); the homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 30,000 g; and the membranes were solubilized in 20 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS). Solubilized membranes were incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 100 nM [35S]GTPγS in 10 mM HEPES with 50 nM IGFBP-5 (Austral Biologicals, San Ramon, CA) in the presence or absence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). The reaction was stopped with 10 volumes of 100 mM Tris·HCl medium (pH 8.0) containing 20 μM GTP, and the membranes were incubated for 2 h on ice in wells precoated with a specific Gα antibody. After adherent membranes were washed with phosphate buffer, the radioactivity from each well was counted by liquid scintillation.

Minigene construction and transient transfection of cultured smooth muscle cells.

The participation of Gαi- and Gβγ-subunits was investigated by transient transfection expression of either a cDNA minigene encoding the last COOH-terminal 11 amino acids, which block the effects mediated via Gαi or expression of cDNA encoding a Gβγ-scavenging peptide, which blocks the effects mediated via Gβγ as described previously (21, 28). The oligonucleotide sequence corresponding to the COOH-terminal 11-amino-acid residues of Gαi in random order was synthesized and ligated into pcDNA 3.1(+) as a control scrambled sense minigene. Human intestinal smooth muscle cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of Gαi inhibitory minigene, control scrambled sense minigene, or Gβγ-scavenging peptide plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine transfection reagent according to manufacturer's direction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Experiments were performed after 48 h at which time transfection efficiency was ∼75–80% for each cDNA used as monitored by cotransfection of pGreen Lantern-1.

Immunoblot analysis.

Analysis of phosphorylated signaling proteins was performed by immunoblot analysis using standard methods (14, 15). Briefly, protein in cell lysate samples containing equal amounts of total protein measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were separated with SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were incubated overnight with specific antibodies recognizing the protein of interest: Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204), p38 MAPK, phospho-p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), or type I collagen (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Membranes were reblotted to measure total (phosphorylated plus nonphosphorylated) protein or β-actin (Cell Signaling Technologies) where appropriate. Bands of interest were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence using a FluoChem 8800 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). The resulting digital images were quantified using AlphaEaseFC version 3.1.2 software. Densitometric values for protein bands were reported in arbitrary units above background values after normalization to total protein levels or β-actin.

[3H]Thymidine incorporation assay.

Proliferation of smooth muscle cells in culture was measured by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine as described previously (11, 15, 18). Briefly, quiescent cells were incubated for 24 h in serum-free DMEM and stimulated with IGFBP-5 for an additional 24 h. The IGF-I-independent effects of IGFBP-5 were determined by the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). During the final 4 h of incubation, 1 μCi/ml [3H]thymidine was added to the medium. [3H]Thymidine incorporation into the perchloric acid extractable pool was used as a measure of DNA synthesis.

IGF-I measurement.

Production of IGF-I was measured in conditioned media from cells growing in culture as described previously (18). Briefly, transfected cells were incubated for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, and the conditioned media was collected and clarified by centrifugation. Free IGF-I was measured in acid-ethanol extracted samples using an IGF-I-specific ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). This assay has no appreciable cross reactivity with IGF-II, insulin, or IGF binding proteins. Results were calculated as picomoles IGF-I per milligram protein per 24 h.

Statistical analysis.

Values given represent the means ± SE of n experiments, where n represents the number of experiments on specimens derived from separate intestinal specimens or primary cultures. Statistical significance was tested by Student's t-test for either paired or unpaired data as was appropriate with P < 0.05.

RESULTS

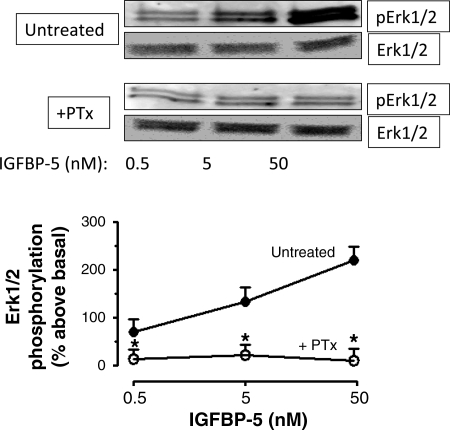

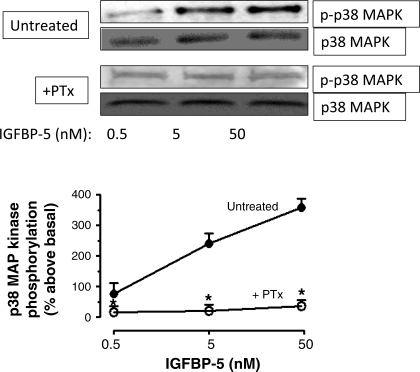

Effect of PTx on IGFBP-5-stimulated phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK.

We have shown previously that direct, IGFBP-5-dependent Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) and p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation was rapid, attaining a maximum within 5 min, and was concentration dependent with maximal activation occurring with 50 nM IGFBP-5 (18). These effects were independent of its ability to modulate the binding and the effects of IGF-I mediated by the IGF-I receptor. In the present study, all experiments included a 30-min preincubation with the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM), to isolate the IGF-I-independent effects of IGFBP-5 (23). In cells treated in this fashion, IGF-I receptor tyrosine phosphorylation is abolished. Treatment of quiescent human intestinal smooth muscle cells with IGFBP-5 for 5 min elicited concentration-dependent Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation (50 nM: 200 ± 18% above basal) that was abolished in the presence of PTx (400 ng/ml) (Fig. 1). IGFBP-5 also induced rapid concentration-dependent p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation (50 nM: 350 ± 24% above basal) that was abolished in the presence of PTx (Fig. 2). The ability of PTx to abolish IGFBP-5-stimulated activation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK implied the participation of an inhibitory heterotrimeric G protein, Gi, in the signaling cascade (9).

Fig. 1.

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)-5-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation is abolished by pertussis toxin (PTx). Densitometric analysis showing IGFBP-5 stimulates concentration-dependent Erk1/2 phosphorylation that is PTx sensitive in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Inset: Representative immunoblots of Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation and total Erk1/2. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 5 min with IGFBP-5 alone (•) or in the presence of 400 ng/ml PTx (○). All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed in relative densitometric units normalized to total Erk1/2 levels. Values represent the means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells.

Fig. 2.

IGFBP-5-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation is abolished by PTx. Densitometric analysis showing IGFBP-5 stimulates concentration-dependent p38 MAPK phosphorylation that is PTx sensitive in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Inset: representative immunoblots of p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation and total p38 MAPK. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 5 min with IGFBP-5 alone (•) or in the presence of 400 ng/ml PTx (○). All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed in relative densitometric units normalized to total p38 MAPK levels. Values represent the means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells.

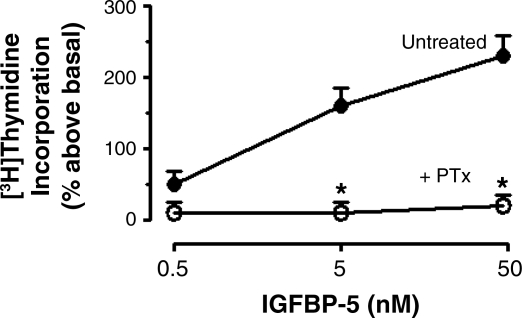

Effect of PTx on IGFBP-5-stimulated proliferation.

IGFBP-5 stimulated a concentration-dependent increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation (50 nM: 230 ± 20% over basal) that was also abolished by 60-min preincubation and continued presence of 400 ng/ml PTx (Fig. 3). The ability of PTx to abolish IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation, like that on signaling intermediate activation, implied that IGFBP-5-stimulated proliferation also involved activation of Gi.

Fig. 3.

IGFBP-5-induced [3H]thymidine incorporation is abolished by PTx. IGFBP-5 elicits concentration-dependent increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation that is PTx sensitive in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 24 h with IGFBP-5 alone (•) or in the presence of 400 ng/ml PTx (○). All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as a percent above basal (basal: 306 ± 29 cpm/mg protein). Values represent the means ± SE of 5 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells.

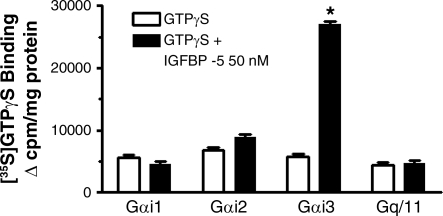

Identification of inhibitory G proteins activated by IGFBP-5.

The notion that IGFBP-5-induced Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK phosphorylation and growth involved the participation of an inhibitory G protein in human intestinal smooth muscle cells was investigated further by identification of the specific inhibitory G protein activated by IGFBP-5 (16, 28). IGFBP-5 (50 nM) selectively increased the activity of Gαi3 340 ± 45% above basal (basal: 6,340 ± 850 cpm/mg protein) (Fig. 4). IGFBP-5 did not affect the activity of Gαi1, Gαi2, or Gq/11 (Fig. 4). The presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (23), AG 1024 (1 μM), did not alter IGFBP-5-stimulated activation of Gαi3 (IGFBP-5: 26,929 cpm/mg protein vs. IGFBP-5 + AG1024: 26,258 cpm/mg protein, n = 4). It is worth noting that we have previously shown that IGF-I-stimulated growth is partially mediated by activation of Gi2, leading to subsequent Erk1/2 activation (16). Taken together, these results imply that activation of Gαi3 by IGFBP-5 was specific and independent of the ability of IGFBP-5 to modulate the effects of IGF-I acting via the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase.

Fig. 4.

IGFBP-5 selectively activates Gi3. IGFBP-5 (50 nM) caused a significant increase in the binding of [35S]GTPγS·Gα complexes to wells precoated with Gαi3 antibody but not to wells precoated with antibody to Gαi1, Gαi2, or Gαq/11. Membranes isolated from human intestinal muscle cells were solubilized in 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate and incubated with [35S]GTPγS in the presence or absence of IGFBP-5 for 20 min. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as the increase in bound radioactivity in cpm/mg protein. Values represent the means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.01 vs. GTPγS alone.

Effects of IGFBP-5 are Gαi3 dependent and Gβγ independent.

Activation of Gi3 by an agonist results in the generation of Gαi3 and Gβγ subunits from Gi3; either of which or both could mediate the effects of IGFBP-5 on activation of signaling intermediates and proliferation by IGFBP-5 or production of IGF-I or type I collagen. The specific functional role of the Gαi or Gβγ subunits derived from IGFBP-5-activated Gi3 was determined in cells in which the effect of Gαi3 was eliminated by transfection of the Gi inhibitory minigene, in cells in which the effect of Gβγ was eliminated by transfection of the Gβγ-scavenging peptide, and in control cells transfected with the control scrambled sense minigene and compared with responses in naïve cells.

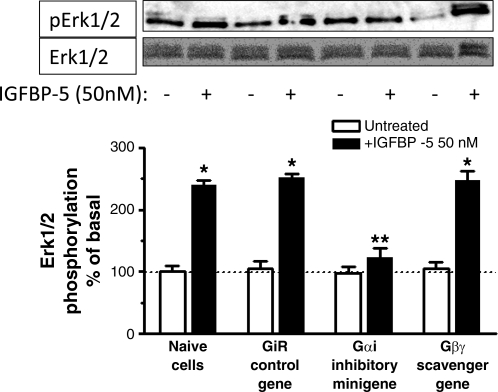

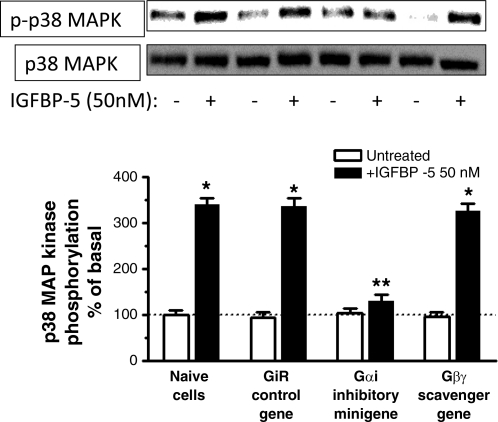

IGFBP-5-stimulated Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation was similar in naïve cells and in cells transfected with the control minigene (naive: 140 ± 7% above basal, control scrambled sense minigene: 152 ± 6%) (Fig. 5). IGFBP-5-stimulated p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation was also not affected (naïve: 340 ± 15% above basal; control scrambled sense minigene: 356 ± 18% above basal) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

IGFBP-5-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation is Gαi dependent. Densitometric analysis showing IGFBP-5-stimulated Erk1/2 phosphorylation is selectively inhibited in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not affected by transfection of the Gαi control scrambled sense minigene or the Gβγ-scavenging minigene in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Inset: representative immunoblots of phospho-Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) and total Erk1/2. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 5 min with 50 nM IGFBP-5. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as percent of basal in relative densitometric units normalized to total Erk1/2. Values represent the means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells; **P < 0.05 vs. GiR-transfected cells stimulated with 50 nM IGFBP-5.

Fig. 6.

IGFBP-5-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation is Gαi dependent. Densitometric analysis showing IGFBP-5-stimulated p38 MAPK phosphorylation is selectively inhibited in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not affected by transfection of the Gαi control scrambled sense minigene or the Gβγ-scavenging minigene in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Inset: representative immunoblots of p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation and total p38 MAPK. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 5 min with 50 nM IGFBP-5. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as a percent of basal in relative densitometric units normalized to total p38 MAPK levels. Values represent the means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells; **P < 0.05 vs. GiR control gene-transfected cells stimulated with IGFBP-5.

In cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene, IGFBP-5-stimulated Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation was inhibited 86 ± 5% (Fig. 5) and p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) phosphorylation was inhibited 91 ± 16% (Fig. 6). Transfection of the Gβγ-scavenging minigene did not affect IGFBP-5-stimulated phosphorylation of either Erk1/2(Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation (1 ± 5% inhibition) (Fig. 5) or p38 MAPK(Thr180/Tyr182) (3 ± 8% inhibition) (Fig. 6).

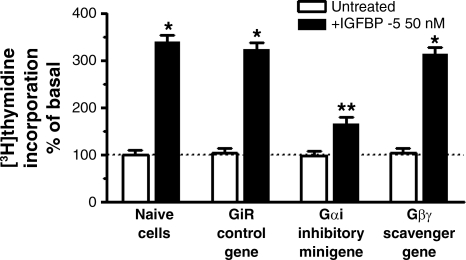

Similar results were obtained when the effects of Gαi on IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation were examined. Basal [3H]thymidine incorporation was similar in naïve cells and in cells transfected with the control scrambled sense minigene (naïve: 306 ± 29 cpm/mg protein; control minigene: 296 ± 24 cpm/mg protein). IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation was also not affected in naïve cells or by transfection of the control scrambled sense minigene (naïve cells: 240 ± 35% above basal; control minigene: 223 ± 16% above basal). However, in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene, IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation was inhibited 66 ± 9% (Fig. 7), whereas, in cells transfected with the Gβγ-scavenging peptide, IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation was not affected (8 ± 7% inhibition) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

IGFBP-5-induced [3H]thymidine incorporation is Gαi dependent. IGFBP-5-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation is selectively inhibited in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not affected by transfection of the Gαi control scrambled sense minigene or the Gβγ-scavenging minigene in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 24 h with 50 nM IGFBP-5. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as a percent of basal (basal: 306 ± 29 cpm/mg protein). Values represent the means ± SE of 5 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells; **P < 0.05 vs. GiR control gene-transfected cells stimulated with IGFBP-5.

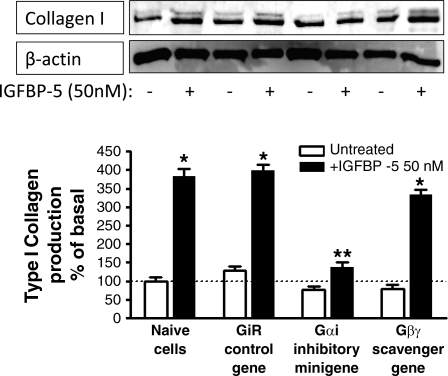

IGFBP-5-induced collagen I production is Gαi dependent.

The role of Gαi3 on IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen production was also examined. Basal collagen production was similar in naïve cells and in cells transfected with the control (scrambled sense) minigene (Fig. 8). IGFBP-5-stimulated collagen production in naïve cells was not affected by transfection of the control minigene (naïve cells: 382 ± 20% of basal; control minigene: 399 ± 15% of basal). However, in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene, IGFBP-5-stimulated production was inhibited 78 ± 7% (Fig. 8), whereas, in cells transfected with the Gβγ-scavenging peptide, IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen production was not affected (11 ± 6% inhibition).

Fig. 8.

IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen production is Gαi3 dependent. IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen production is selectively inhibited in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not affected by transfection of the Gαi control scrambled sense minigene or the Gβγ-scavenging minigene in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Inset: representative immunoblots of IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen production and β-actin control. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 24 h with 50 nM IGFBP-5, and type I collagen was measured in the conditioned medium. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as a percent of basal and normalized to β-actin levels. Values represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells; **P < 0.05 vs. GiR control gene-transfected cells stimulated with IGFBP-5.

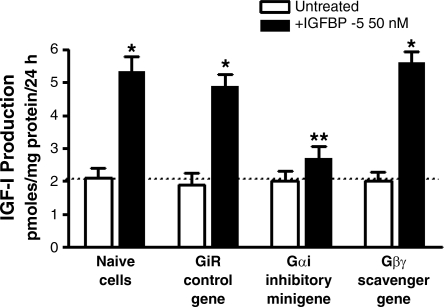

IGFBP-5-induced IGF-I production is Gαi dependent.

The role of Gαi3 on IGFBP-5-stimulated IGF-I production was also examined. Basal IGF-I production was similar in naïve cells and in cells transfected with the control (scrambled sense) minigene (Fig. 9). Basal IGFBP-5 stimulated IGF-I production in naïve cells was not affected by transfection of the control minigene (naïve cells: 2.10 ± 0.30 pmol/mg protein per 24 h; control minigene: 1.87 ± 0.36 pmol/mg protein per 24 h). However, IGFBP-5 stimulated IGF-I production from naïve cells, 3.25 ± 0.44 pmol/mg protein per 24 h above basal, and was inhibited 81 ± 9% in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene (Fig. 9), whereas, in cells transfected with the Gβγ-scavenging peptide, IGFBP-5-stimulated IGF-I production was inhibited 2 ± 14%.

Fig. 9.

IGFBP-5-stimulated IGF-I production is Gαi3 dependent. IGFBP-5-stimulated IGF-I production is selectively inhibited in cells transfected with the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not affected by transfection of the Gαi control scrambled sense minigene or the Gβγ-scavenging minigene in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Quiescent cells were stimulated for 24 h with 50 nM IGFBP-5, and IGF-I was measured by ELISA in the conditioned medium. All experiments were performed in the presence of the IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024 (1 μM). Results are expressed as picomoles IGF-I per milligram protein per 24 h. Values represent the means ± SE of 4–6 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells; **P < 0.05 vs. GiR control gene-transfected cells stimulated with IGFBP-5.

DISCUSSION

A variety of mechanisms have been elucidated by which IGFBP-5 exerts IGF-I-independent effects on cell function in addition to its ability to modulate the binding of IGF-I to the IGF-IR. IGFBP-5 possesses both a COOH-terminal nuclear localization sequence that has been shown to mediate β-importin-dependent translocation and subsequent binding to members of the nuclear receptor superfamily (25, 27). IGFBP-5 regulates heterodimerization of RXRα and vitamin D receptors in osteoblasts and modulates vitamin D-dependent differentiation (26). IGFBP-5 also contains an NH2-terminal consensus transactivation domain that has been shown to possess strong IGF-I-independent transactivation activity; however, a function for this property has not been elucidated (31). Interestingly, in vascular smooth muscle cells, IGFBP-5-dependent nuclear effects required secretion of IGFBP-5 before cell entry and translocation to the nucleus (31).

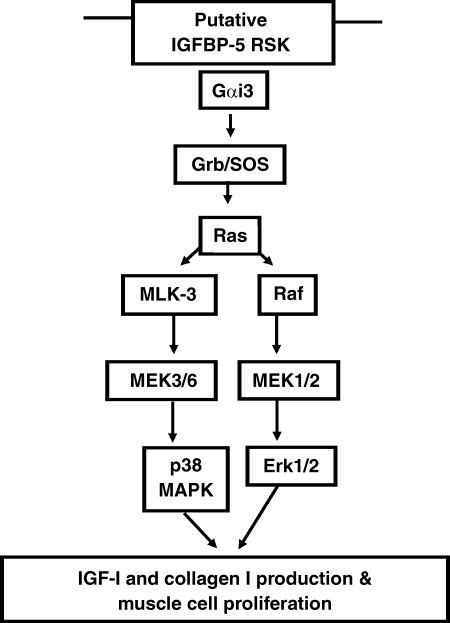

The findings of the present study suggest that the IGF-I-independent effects of IGFBP-5 in human intestinal smooth muscle cells are mediated by binding to a cell surface receptor coupled to activation of Gi3 rather than by nuclear translocation. IGFBP-5 stimulates Gαi3-dependent, Ras-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK that is jointly coupled to proliferation and to Gαi3-dependent type I collagen production and IGF-I production (18) (Fig. 10). The evidence supporting the participation of Gi3 in IGFBP-5-mediated effects in human intestinal smooth muscle cells can be summarized as follows: 1) IGFBP-5-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK is PTx sensitive; 2) IGFBP-5-induced [3H]thymidine incorporation is PTx sensitive; 3) IGFBP- 5 selectively activates Gi3, but not Gi1, Gi2, or Gq/11; 4) IGFBP-5-induced Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK phosphorylation and [3H]thymidine incorporation are abolished by transfection of Gαi inhibitory minigene but not by a Gβγ-scavenging peptide; and 5) IGFBP-5-stimulated type I collagen and IGF-I production are also abolished by transfection of the Gαi inhibitory minigene but not by the Gβγ-scavenging peptide, implying that these effects of IGFBP-5 were mediated by the Gαi3 subunit of Gi3. None of these effects mediated by Gi3 are altered by the presence of IGF-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG1024. In previous studies, we have shown that IGF-I activates only Gi2 but not Gi3 (18). The ability of IGF-I to activate Gi2 and its Gi2-dependent effects are blocked by either an IGF-IR-neutralizing antibody or peptide antagonist; the IGF-I-independent effects of IGFBP-5 are not blocked by these agents (16, 18). Taken together, these findings indicate that IGFBP-5 stimulates muscle cell growth, IGF-I production, and type I collagen production independently of IGF-I. Although IGFBP-5 nuclear translocation has not been specifically excluded in the present study, neither of these mechanisms would be expected to be sensitive to inhibitors of G protein activation, such as PTx, to Gi inhibitory minigene expression, or to inhibitors of cytosolic signaling intermediates as has been shown in the current study and previously (18).

Fig. 10.

Mechanisms mediating IGFBP-5 effects in human smooth muscle cells. The schema outlines that the IGF-I-independent direct effects of IGFBP-5 are mediated through the putative IGFBP-5 receptor serine kinase coupled to Giα3. Activation of Gi3 leads to Gαi3-dependent activation of cytosolic signaling cascades coupled to Erk1/2-dependent and p38 MAPK-dependent muscle cell proliferation, IGF-I production, and type I collagen production (18).

Inhibitory G proteins have also been implicated in the response of various cells to other members of the IGF family. IGF-I is coupled to activation of Gi2, leading to Gβγ-dependent Erk1/2 phosphorylation stimulation of growth and concomitant Gαi2-dependent inhibition of growth-inhibitory adenylate cyclase in human intestinal muscle (16). In rat hippocampal cells, the IGF-IIR is coupled to Gαi2 and regulation of central cholinergic function (8). In mouse C2C12 muscle cells, IGFBP-5 binds IGF-II and facilitates its interaction with the IGF-IR, thereby upregulating IGF-II expression. This autocrine mechanism is not operative in human intestinal smooth muscle cells, which produce picomolar levels of IGF-II and in which IGF-II-dependent activation of the IGF-IR and signaling is nil. IGF-II is a weak stimulator of muscle proliferation even at supraphysiological levels of stimulation (16). That which does occur is not sensitive to PTx (13, 16).

Production of extracellular matrix components by intestinal smooth muscle cells is also increased in stricturing Crohn's disease including fibronectin and vitronectin. IGFBP-5 binds with high affinity to vitronectin, and, in the presence of IGFBP-5, the response of porcine aortic smooth muscle cells to IGF-I was enhanced (22). In contrast, although IGFBP-5 binds with high affinity also to fibronectin, this interaction triggers IGFBP-5 proteolysis, thus limiting its IGF-I-dependent effects in embryonic cells (32). In Hs578T breast cancer cells, which do not respond to IGF-I, IGFBP-5 acts to limit the attachment of cells to extracellular matrix via fibronectin (20). These varied mechanisms and responses highlight the fact that the specific interactions and effects of IGFBP-5 with components of the extracellular matrix are both species and tissue specific.

IGFBP-5 and IGF-I expression by smooth muscle cells is concomitantly increased within the muscularis propria in regions of stricturing Crohn's disease compared with normal intestine. Both play a key role in the development of the smooth muscle cell hyperplasia that accompanies stricture formation. IGF-I stimulates smooth muscle cell growth, increases production of type I collagen, and upregulates IGFBP-5 expression in human intestinal smooth muscle; a similar process has been identified in rat colonic smooth muscle (11, 13, 34). IGFBP-5, in addition to enhancing the effects of IGF-I on smooth muscle cell growth, acts independently of IGF-I, not only to stimulate smooth muscle cell growth, but also directly stimulate secretion of IGF-I and type I collagen (18). In summary, the positive feedback loop between endogenous IGF-I and endogenous IGFBP-5 regulates smooth muscle growth and type I collagen and IGF-I production in normal intestinal smooth muscle and is likely to contribute to the excess smooth muscle hyperplasia and excess extracellular matrix production that are two hallmarks of the strictured intestine of Crohn's disease.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grant DK-49691 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases to J. Kuemmerle.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures to make and declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andress DL. Heparin modulates the binding of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-5 to a membrane protein in osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem 270: 28289–28296, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andress DL. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) stimulates phosphorylation of the IGFBP-5 receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E744–E750, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter RC. Signalling pathways involved in antiproliferative effects of IGFBP-3: a review. Mol Pathol 54: 145–148, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berfield AK, Andress DL, Abrass CK. IGFBP-5(201–218) stimulates Cdc42GAP aggregation and filopodia formationin migrating mesangial cells. Kidney Int 57: 1991–2003, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushman TL, Kuemmerle JF. IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 production by human intestinal muscle: reciprocal regulation by endogenous TGF-β1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G1282–G1290, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler AA, LeRoith D. Minireview: tissue-specific versus generalized gene targeting of the IGF1 and IGF1R genes and their roles in insulin-like growth factor physiology. Endocrinology 142: 1685–1688, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanayan S, Firth SM, Butt AJ, Baxter RC. Growth inhibition by insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in T47D breast cancer cells requires transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) and the type II TGF-beta receptor. J Biol Chem 275: 39146–39151, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkes C, Jhamandas JH, Harris KH, Fu W, MacDonald RG, Kar S. Single transmembrane domain insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor regulates central cholinergic function by activating a G-protein-sensitive, protein kinase C-dependent pathway. J Neurosci 26: 585–596, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakobs KH, Aktories K, Schultz G. Mechanism of pertussis toxin action on the adenylate cyclase system. Inhibition of the turn-on reaction of the inhibitory regulatory site. Eur J Biochem 140: 177–181, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones JI, Gockerman A, Busby WH, Jr, Wright G, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 stimulates cell migration and binds to the alpha 5 beta 1 integrin by means of its Arg-Gly-Asp sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 10553–10557, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuemmerle JF. Autocrine regulation of growth in cultured human intestinal muscle by growth factors. Gastroenterology 113: 817–824, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuemmerle JF. Endogenous IGF-I promotes survival of human intestinal muscle cells by Akt-dependent inhibition of GSK-3β activity. Mol Biol Cell 13: 165a, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuemmerle JF. Endogenous IGF-I regulates IGF binding protein production in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278: G710–G717, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuemmerle JF. IGF-I elicits growth of human intestinal smooth muscle cells by activation of PI3K, PDK-1, and p70S6 kinase. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G411–G422, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuemmerle JF. Occupation of αvβ3-integrin by endogenous ligands modulates IGF-I receptor activation and proliferation of human intestinal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G1194–G1202, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuemmerle JF, Murthy KS. Coupling of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor tyrosine kinase to Gi2 in human intestinal smooth muscle: Gbetagamma-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and growth. J Biol Chem 276: 7187–7194, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuemmerle JF, Murthy KS, Bowers JG. IGFBP-3 activates TGF-β receptors and directly inhibits growth in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G795–G802, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuemmerle JF, Zhou H. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) stimulates growth and IGF-I secretion in human intestinal smooth muscle by Ras-dependent activation of p38 MAP kinase and Erk1/2 pathways. J Biol Chem 277: 20563–20571, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Fawcett J, Widmer HR, Fielder PJ, Rabkin R, Keller GA. Nuclear transport of insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in opossum kidney cells. Endocrinology 138: 1763–1766, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCaig C, Perks CM, Holly JMP. Intrinsic actions of IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 on Hs578T breast cancer epithelial cells: inhibition or accentuation of attachment and survival is dependent upon the presence of fibronectin. J Cell Sci 115: 4293–4303, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murthy KS. Inhibitory phosphorylation of soluble guanylyl cyclase by muscarinic m2 receptors via Gbetagamma-dependent activation of c-Src kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325: 183–189, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam T, Moralez A, Clemmons D. Vitronectin binding to IGF binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) alters IGFBP-5 modulation of IGF-I actions. Endocrinology 143: 30–36, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parrizas M, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Wertheimer E, LeRoith D. Specific inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity and biological function by tyrphostins. Endocrinology 138: 1427–1433, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santer FR, Bacher N, Moser B, Morandell D, Ressler S, Firth SM, Spoden GA, Sergi C, Baxter RC, Jansen-Durr P, Zwerschke W. Nuclear insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 induces apoptosis and is targeted to ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis. Cancer Res 66: 3024–3033, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schedlich LJ, Le Page SL, Firth SM, Briggs LJ, Jans DA, Baxter RC. Nuclear import of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 and -5 is mediated by the importin beta subunit. J Biol Chem 275: 23462–23470, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schedlich LJ, Muthukaruppan A, O'Han MK, Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 interacts with the vitamin D receptor and modulates the vitamin D response in osteoblasts. Mol Endocrinol 21: 2378–2390, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schedlich LJ, Young TF, Firth SM, Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP)-3 and IGFBP-5 share a common nuclear transport pathway in T47D human breast carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 273: 18347–18352, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sriwai W, Zhou H, Murthy KS. G(q)-dependent signalling by the lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA(3) in gastric smooth muscle: reciprocal regulation of MYPT1 phosphorylation by Rho kinase and cAMP-independent PKA. Biochem J 411: 543–551, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng B, Murthy KS, Kuemmerle JF, Grider JR, Sase K, Michel T, Makhlouf GM. Expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human and rabbit gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G342–G351, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Niu W, Nikiforov Y, Naito S, Chernausek S, Witte D, LeRoith D, Strauch A, Fagin JA. Targeted overexpression of IGF-I evokes distinct patterns of organ remodeling in smooth muscle cell tissue beds of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 100: 1425–1439, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Q, Li S, Zhao Y, Maures TJ, Yin P, Duan C. Evidence that IGF binding protein-5 functions as a ligand-independent transcriptional regulator in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 94: E46–E54, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Q, Yan B, Li S, Duan C. Fibronectin binds insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 and abolishes its ligand-dependent action on cell migration. J Biol Chem 279: 4269–4277, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yakar S, Liu JL, Stannard B, Butler A, Accili D, Sauer B, LeRoith D. Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7324–7329, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann EM, Li L, Hou YT, Cannon M, Christman GM, Bitar KN. IGF-I induces collagen and IGFBP-5 mRNA in rat intestinal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G875–G882, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]