ABSTRACT

Colonic obstruction is common with malignancy as the most common cause. Endoscopic placement of intraluminal self-expanding stents is a newer option to manage this challenging problem. In benign disease, endoscopic dilatation may play a role whereas stenting can serve as a bridge to surgery. Indications and placement techniques are discussed along with a summary of published results and complications.

Keywords: Colonic obstruction, stents, self-expanding, endoscopy, dilatation

Colonic obstruction is a common clinical problem in the United States; the majority of obstructions are due to malignant processes. Approximately 8 to 29% of patients with colorectal cancer initially present with symptoms of partial or complete bowel obstruction, most of which are left-sided and either stage III or IV.1,2 There are several options to manage patients with large bowel obstruction. Traditionally, patients were resuscitated; evaluated with a contrast study such as a water-soluble enema (Fig. 1), computed tomography (CT) scan, or colonoscopy; then taken to surgery. Surgical options for right-sided lesions usually involved a segmental resection and an ileocolic anastomosis or ileostomy depending on the status of the bowel and patient, as well as the experience of the surgeon. Management of left-sided lesions traditionally varied from a segmental resection and colostomy, a subtotal colectomy, and ileorectal anastomosis or ileostomy. These emergency procedures had an associated mortality of 10 to 30% and a morbidity of 10 to 36%.1,2,3 Due to their age and comorbidities, many of the patients receiving ostomies did not have their stomas closed. In addition, the time spent recovering from therapy or associated with their morbidity or complications from surgery often delayed or prevented chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Quality of life and the cost of ostomy supplies has also been an issue. These limitations encouraged development of other options—most notably self-expanding intraluminal stenting. Intraluminal stenting can be used for palliation or as a bridge to surgery (converting an emergency procedure to an elective one). The use of stents for nonmalignant obstruction has been very limited and not especially optimistic. Selected patients such as those with anastomotic strictures or Crohn disease may benefit from endoscopic dilatation. In this article, I will review the indications, techniques and published results of intraluminal stents for colonic obstructions and dilatation.

Figure 1.

Contrast enema demonstrating an obstructing colonic lesion.

INDICATIONS

Since their introduction in 1991, colonic stents have become an important method of palliation for obstruction in colorectal cancer patients, especially those with unresectable metastatic disease. These self-expanding metallic stents can potentially dilate the lumen to a near-normal diameter, providing quick relief of symptoms, and in some cases, allowing endoscopic or radiologic assessment of the proximal colon. Stents can be placed in patients using minimal sedation, without need of prior endoscopic dilation and a low risk of complications such as perforation or tumor fracture. Moreover, these stents can be placed across relatively long lesions by overlapping stents in a “stent-within-stent” fashion. In general, the patient's lesion must be accessible to an endoscope and not have an absolute indication for a laparotomy (e.g., perforation).

Most patients with benign strictures are better managed with traditional operative techniques. The morbidity associated with long-term stents in this patient group has been prohibitive. However, increasing experience with stents used as a bridge to surgery in selected patients with benign strictures is being accumulated. Endoscopic balloon dilatation has also been successful in selected patients with colonic anastomotic strictures, Crohn's strictures, ischemic strictures, and endometriotic strictures.

TECHNIQUE

Several intraluminal stents are currently available (Table 1). They are composed of stainless steel or alloys. Nitinol is an alloy of nickel and titanium, which has increased flexibility that is helpful for stenting sharply angulated regions at the cost of lesser radial force relative to stents made from other metals. Elgiloy is an alloy of cobalt, nickel, and chromium and is corrosion resistant and capable of generating high radial forces. Stents are produced in coated and uncoated versions. Coated stents may have lower rates of tissue ingrowth, which may produce a longer patency but has a higher rate of migration. There is some evidence that they may aid in fistula closure.4,5 Currently, only uncoated stents are approved for use in the colon. Colonic stents range in predeployment diameter from 10 to 30 F and postdeployment diameter of 20 to 35 mm, and 40 to 120 mm in length. Most have a proximal and/or distal flare to prevent migration. The stents are generally packaged in compressed form and constrained on a delivery device.

Table 1.

Available Stents

| Stent | Manufacturer | Composition | Deployment | Size (Diameter/Length) | List Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTS, through the scope; OCW, over the wire. | |||||

| Wallflex® | Boston Scientific, Natick, MA | Elgiloy | TTS | 27–30 mm 60–120 mm | |

| Wallstent® | Boston Scientific | Stainless steel | TTS | $1775 | |

| Z-stent® | Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN | Stainless steel | OTW | 25 mm 40–120 mm | $1000– $1400 |

| Ultraflex Precision® | Boston Scientific | Nitinol | OTW | 30/25 mm 57–117 mm | $1775 |

Stents can be deployed through the scope (TTS) with or without a guide wires, or passed under fluoroscopic control over an endoscopically or fluoroscopically placed guide wire. My preference is an Enteral Wallflex 120 mm in length (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). TTS stents are easier to place through proximal or angulated lesions.

The following is a description of the technique I typically use. Patients are taken to the endoscopy unit and placed on a fluoroscopically capable table. After placement of monitors and nasal oxygen, the patient is placed into a left lateral position and sedated. A colonoscope is inserted and advanced to the obstructing lesion (Fig. 2). Fluoroscopy is used to observe the lesion location and the patient's position is altered to obtain the best fluoroscopic view. Intraluminal contrast may assist in this localization and positioning. If the lumen appears tight, a flexible guide wire is inserted through the working port of the colonoscope and under direct vision, it is gently passed across the obstruction (Fig. 3). If the lumen is not so tight the stent itself may be passed across the lesion. Fluoroscopy confirms that the wire or catheter has passed through the lesion. If a guide wire was used, a TTS stent is then passed through the scope over the guide wire and passed across the lesion. Radiopaque markers of the stent help position it across the obstructing lesion. Under fluoroscopic visualization the stent is deployed slowly (Fig. 4). Some repositioning is possible prior to complete stent deployment. Optimally, the configuration of the deployed stent will have a flare proximal and distal to the stricture with a narrowed neck at the stricture. Successful deployment is often associated with a rush of gas or colonic contents through the deployed stent. Following successful deployment, a contract study or plain film will confirm appropriate deployment (Fig. 5). If the stricture is long or the stent does not have adequate extension across the stenosis, a second stent can be placed overlapping a portion of the initial stent. Attempting to pass the colonoscope through the stent after deployment should be avoided as the metal edges of the stent can damage the colonoscope (Fig. 6).

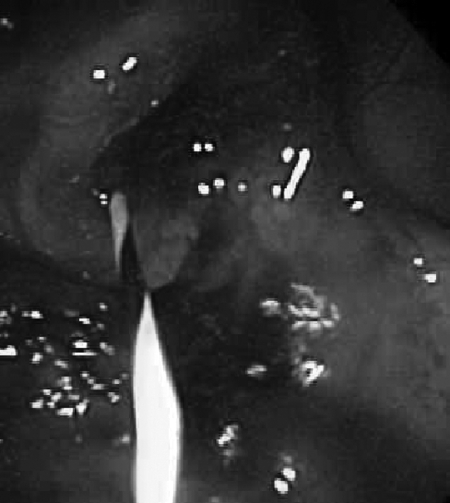

Figure 2.

Colonoscopic view of obstructing lesion.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic view of guide through obstructing lesion.

Figure 4.

Undeployed stent is passed through stricture.

Figure 5.

X-ray of stent in place.

Figure 6.

Endoscopic view of deployed stent.

The technique of balloon dilatation is very similar, but fluoroscopy is used less often as the strictures suitable to dilatation are usually shorter. Several endoscopically guided balloons are available. For colonic use, the balloons range in size from 6 to 20 mm diameter. The technique involves placing a guide wire across the stricture. The balloon catheter is advanced over the guide wire to the midpoint of the stricture and inflated with a pressure- or volume-controlled handle. After removal of the balloon, the dilatated stricture is usually examined endoscopically.

RESULTS

Stenting has been more successful in shorter, distal lesions and with colonic primaries. Technical failure is usually due to the inability to pass a guide wire or stent catheter across the obstruction, most often because of the angulation of the tumor. Clinical failure is usually defined as failure to relieve the obstruction or the occurrence of a major complication.

Malignant Strictures

Three reviews have evaluated the safety and efficacy of stents in dealing with colorectal malignant obstruction. The first examined 29 publications including 598 patients. Technical success was achieved in 92% and clinical success in 88%.6 A successful bridge to surgery was accomplished in 85% of 162 stent insertions and the mean time to surgery was 8.9 days (range 1 to 115 days). A second review of 54 case series (1,198 patients) by Sebastian and colleagues found that stenting was technically successful as a bridge to surgery in 92% of 407 cases and clinically successful in 72%.5 In 791 palliative patients, the technical success was 93% and clinical success in 91%. Complications included perforation in 3.8%, stent migration in 11.8% and reobstruction in 7.3%.

The third review included 88 articles, 15 of which were comparative.7 The median rates of technical and clinical success were 96.2% and 92%, respectively. The median time between stenting and elective surgery was 5.8 days (range 2 to 16 days). The review concluded that stenting followed by elective surgery appeared safer and more effective than emergency surgery, with higher rates of primary anastomosis, lower rates of colostomy, shorter hospital stays, and lower overall complication rates.

Several specific situations deserve additional comment. In a retrospective series of 80 patients who underwent colonic stent placement for malignant large bowel obstruction, stents were successfully placed in 70 patients (87.5% overall technical success rate).8 Satisfactory symptomatic relief and clinical decompression was achieved in 67 patients (83.7% overall clinical success rate). Two perforations occurred in this series, one of which resulted in death. Other complications included stent migration resulting in expulsion, reobstruction, and intractable tenesmus. Stenting of cancers in the mid and low rectum may result in debilitating urgency and incontinence.

A recent series of 52 patients with malignant obstruction secondary to either primary or recurrent disease, who underwent stent placement by colorectal surgeons, reported that 50 out of 52 were successfully palliated.9 One patient had a perforation, and in another patient obstruction was not relieved because of multiple sites of obstruction. The complication rate in this series was 25%; migration was the most common complication (15.4%), followed by reobstruction secondary to tumor ingrowth (3.8%), perforation, colovesical fistula, and severe tenesmus (2% each). Surgery was required in 17.3%, mostly due to complications or recurrent obstruction. Complications reported in the literature on colonic stents include stent malpositioning, migration, tumor ingrowth (through the stent interstices), tumor overgrowth (beyond the ends of a stent), perforation, stool impaction, bleeding, tenesmus, and postprocedure pain. The insertion technique and type of stent remains under discussion.

Another retrospective review of patients presenting with obstructing colon cancer with synchronous metastases, compared 31 patients with stents to 27 who had primary surgery.10 Although morbidity and mortality was similar, the stent patients had fewer stomas and were able to begin chemotherapy sooner than the surgery patients. This potential advantage is questioned in another study by Kim and colleagues from Korea.11 They compared 35 patients with left-sided colonic obstruction who received stents to a matched group of 350 patients who underwent elective surgery for stage-matched cancer. The 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates were better for the elective patients. However, this may reflect adverse effects of obstruction (not compensated by stage matching) rather than stenting.

Finally, a review of 21 patients with right-sided malignant obstructions managed with stents revealed an initial technical success of 95% and 85% with complete relief of obstruction.12 There were no procedure-related complications and the authors felt that success rates were similar to distal colonic stenting.

Nonmalignant Strictures

Intestinal strictures result from several conditions. Benign conditions such as inflammation (inflammatory bowel disease) or postoperative anastomosis often respond to dilatation. In 1989, Aston et al reported their experience with nine patients who underwent balloon dilatation of colon and rectal anastomotic strictures. Six of the nine strictures resolved after a single dilatation.13 Also in 1989, Stone and Bloom described balloon dilatation of obstructing colorectal cancer in three patients allowing elective onstage colon resection or ND: YAG laser palliation in a clean field.14 In 1991, Williams and Palmer reported the balloon dilatation of seven patients with obstructing symptoms secondary to Crohn's strictures.15 Five patients had strictures at the site of a previous ileotransverse colon anastomosis. They obtained a sustained improvement in five patients over a follow-up period of 18 to 24 months, but were unsuccessful in two patients. In a more recent, larger series, Dear and Hunter report balloon dilatation in 22 patients with Crohn's strictures.16 Sixteen patients were successfully dilated although one third of the patients required more than two dilatations. Six patients failed balloon treatment and required surgery. There were no complications after any of the 71 dilatations performed. Lastly, Miller et al report successfully treating an endometriotic stricture of the sigmoid colon.17 Thus, balloon dilatation in selected patients appears safe and effective in eliminating the need for additional surgeries.

Small and colleagues described 23 patients who underwent intraluminal stent placement for benign colonic strictures.18 Technical success was obtained in 95% of the patients, but complications occurred in 38%. Eighty-seven percent of these complications occurred after 7 days of placement. The authors felt that intraluminal stents were useful as a bridge to surgery, which should be performed within 7 days if possible.

SUMMARY

The published data suggests that in experienced centers, an initial attempt at stent placement by an experienced multidisciplinary team is the preferred option for malignant obstruction. Endoscopic procedures can serve as a bridge to surgery in potentially curable, fit patients and provide effective and durable palliation for selected patients with malignant obstruction. Dilatation may be used in selective benign strictures; stenting may provide a bridge to surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck D E. In: Cameron JL, Cameron AM, editor. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; Use of stents for colonic obstruction. In press.

- 2.Deans G T, Krukowski Z H, Irwin S T. Malignant obstruction of the left colon. Br J Surg. 1994;81(9):1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandrup P, Lund L, Balslev I. Surgical treatment of acute malignant large bowel obstruction. Eur J Surg. 1992;158(8):427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tierney W, Chuttani R, Croffie J, et al. Enteral stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(7):920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(10):2051–2057. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khot U P, Lang A W, Murali K, Parker M C. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg. 2002;89(9):1096–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watt A M, Faragher I G, Griffin T T, Rieger N A, Maddern G J. Self-expanding metallic stents for relieving malignant colorectal obstruction: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):24–30. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000261124.72687.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camúñez F, Echenagusia A, Simó G, Turégano F, Vázquez J, Barreiro-Meiro I. Malignant colorectal obstruction treated by means of self-expanding metallic stents: effectiveness before surgery and in palliation. Radiology. 2000;216(2):492–497. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law W L, Choi H K, Lee Y M, Chu K W. Palliation for advanced malignant colorectal obstruction by self-expanding metallic stents: prospective evaluation of outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(1):39–43. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karoui M, Charachon A, Delbaldo C, et al. Stents for palliation of obstructive metastatic colon cancer: impact on management and chemotherapy administration. Arch Surg. 2007;142(7):619–623. discussion 623. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.7.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J S, Hur H, Min B S, Sohn S K, Cho C H, Kim N K. Oncologic outcomes of self-expanding metallic stent insertion as a bridge to surgery in the management of left-sided colon cancer obstruction: comparison with nonobstructing elective surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33(6):1281–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Repici A, Adler D G, Gibbs C M, Malesci A, Preatoni P, Baron T H. Stenting of the proximal colon in patients with malignant large bowel obstruction: techniques and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(5):940–944. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aston N O, Owen W J, Irving J D. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of colonic anastomotic strictures. Br J Surg. 1989;76(8):780–782. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone J M, Bloom R J. Transendoscopic balloon dilatation of complete colonic obstruction. An adjunct in the treatment of colorectal cancer: report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(5):429–431. doi: 10.1007/BF02563698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams A J, Palmer K R. Endoscopic balloon dilatation as a therapeutic option in the management of intestinal strictures resulting from Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1991;78(4):453–454. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dear K L, Hunter J O. Colonoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilatation of Crohn's strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(4):315–318. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller E S, Barnett R M, Williams R B. Sigmoid endometriotic stricture treated with endoscopic balloon dilatation: case report and literature review. Md Med J. 1990;39(12):1081–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small A J, Young-Fadok T M, Baron T H. Expandable metal stent placement for benign colorectal obstruction: outcomes for 23 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(2):454–462. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]