Abstract

Local release of TGF-β during times of high bone turnover leads to elevated levels within the bone microenvironment, and we have shown that TGF-β suppresses osteoclast apoptosis. Therefore, understanding the influences of TGF-β on bone resorbing osteoclasts is critical to the design of therapies to reduce excess bone loss. Here we investigated the mechanisms by which TGF-β sustains suppression of osteoclast apoptosis. We found TGF-β rapidly increased leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) expression and secretion by phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic-dependent and -independent signaling pathways. TGF-β also induced suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) expression, which was required for TGF-β or LIF to promote osteoclast survival by. Blocking LIF or SOCS3 blocked TGF-β promotion of osteoclast survival, confirming that LIF and SOCS3 expression are necessary for TGF-β-mediated suppression of osteoclast apoptosis. Investigation of the mechanisms by which LIF promotes osteoclast survival revealed that LIF-induced expression of Bcl-XL and repressed Bcl-2 interacting domain expression by activating MAPK kinase, AKT, and nuclear factor-κB pathways. Suppression of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling further increased Bcl-XL expression and enhanced osteoclast survival, supporting that this pathway is not involved in prosurvival effects of TGF-β and LIF. These data show that TGF-β coordinately induces LIF and SOCS3 to promote prosurvival signaling. This alters the ratio of prosurvival Bcl2 family member Bcl-XL to proapoptotic family member Bcl-2 interacting domain, leading to prolonged osteoclast survival.

TGF-β coordinately induces leukemia inhibitory factor and SOCS3 to promote osteoclast survival by increasing Bcl-XL and suppressing Bid expression.

TGF-β has been implicated in excess bone loss conditions such as osteoporosis and osteolytic cancers (1,2,3,4,5). The roles of TGF-β in bone metabolism are complex and likely to be multifactorial (reviewed in Refs. 6 and 7). TGF-β is required for early osteoclast progenitor commitment, and we have shown that TGF-β directly stimulates osteoclast differentiation (8,9). A recent report documented that pharmacological inhibition of TGF-β in mice caused anabolic responses by increasing osteoblast differentiation and anticatabolic effects by suppressing bone resorption (10). This observation supports proosteoclast influences of TGF-β in vivo. In an animal model of osteolytic tumor progression, Futakuchi et al. (11) documented that TGF-β signaling is activated in mature osteoclasts involved in tumor-induced osteolysis and that blocking TGF-β reduced bone loss. Thus, one function of TGF-β may be to promote osteoclast-mediated bone loss by direct influences on the mature cells. We have shown that TGF-β suppresses osteoclast apoptosis, which would increase osteolysis by increasing the number of osteoclasts at sites of tumor growth (12). Thus, proosteoclast TGF-β influences in vivo likely include suppression of mature osteoclast apoptosis.

TGF-β signaling is a complex interplay between intracellular mediators that is likely to be cell type and context dependent. TGF-β is secreted as a latent complex that must be activated to bind to receptor II and initiate signal transduction. There are two distinct signaling pathway classifications that can be activated after receptor activation, the phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) pathway and kinase pathways. The kinase pathways are frequently referred to as SMAD-independent signaling pathways (reviewed in Refs. 13,14,15). Upon TGF-β binding to receptor II, it complexes with receptor I, and this receptor phosphorylates the carboxy terminus of SMAD2 and/or SMAD3, the receptor-regulated SMADs (16). When activated, receptor-regulated SMADs 2 and/or 3 form a complex with SMAD4, and this complex translocates to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, the complex, either by itself or in conjunction with additional proteins, regulates target genes. SMAD3 null mice exhibit an osteopenic phenotype, supporting a key role for SMAD3 in bone metabolism (17). Rapid activation of non-SMAD pathways, which may parallel or even precede SMAD pathway activation, supports direct TGF-β-mediated activation of non-SMAD signaling. Indeed, data are accumulating that one or more non-SMAD signaling pathway is frequently activated by TGF-β (reviewed in Ref. 16). We have shown that both SMAD-dependent and kinase pathway-dependent signaling are required for TGF-β-mediated support of osteoclast survival (12).

Because factors that alter survival will alter the rate at which bone is resorbed, the focus of this study was on the mechanisms by which TGF-β influences osteoclast apoptosis. We have shown that TGF-β promotes osteoclast survival in part by rapid stimulation of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 expression (12). In the studies reported here, we expanded our examination of how TGF-β sustains osteoclast survival by investigating the role of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and its signaling modulator suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) in TGF-β-mediated suppression of osteoclast apoptosis. LIF is a member of the IL-6 superfamily, which is delineated by the use of a common gp130 receptor subunit that dimerizes with the LIF receptor for signaling (reviewed in Ref. 18). In the absence of stimulation, LIF expression levels are very low, but expression can be induced in a variety of tissues (18). Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and TNF-α induce expression, whereas antiinflammatory factors such as glucocorticoids, IL-4, and IL-13 repress expression (19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). Park et al. (28) showed that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Ras/Raf pathway induces LIF expression, which acts in an autocrine manner to influence cell fate. LIF promotes survival of some cell types, but mammary epithelial cells respond to LIF treatment with increased apoptosis (18,29,30,31). There are three known pathways that are activated by LIF: Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3, MAPK kinase (MEK)/ERK, and PI3K/AKT, although PI3K may also contribute to MEK activation (18,32,33). SOCS3 is a negative regulator of JAK/STAT signaling that may act by binding to JAK to prevent STAT activation (31). In this study, we examined the mechanisms by which TGF-β induces LIF and SOCS3, the role of LIF and SOCS3 in TGF-β promotion of osteoclast survival, and the mechanisms by which prosurvival LIF signaling promotes osteoclast survival.

Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals are from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). TGF-β1was purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, MN) and suspended in PBS/0.01% BSA (vehicle).

Osteoclast culture

Marrow cells were obtained from BALB/c mice as outlined previously (34). Marrow was flushed from the long bones with PBS and red blood cells lysed. Cells were incubated at 37 C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator overnight in α-MEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), antibiotic/antimycotic, and 25 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D). The following day, nonadherent cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates (Fischer, Pittsburgh, PA) in the above media with 100 ng/ ml receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand [RANKL; recombinant glutathione-S-transferase-RANKL, a gift from Dr. Beth Lee (Physiology and Cell Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH), generated and purified by affinity chromatography using glutathione sepharose 4B prepacked disposable columns according to the provider (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ)]. Cells were fed fresh media on d 3 and treated as described in the figure legends for specific experiments.

Hoechst and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining and apoptosis quantitation

Cells cultured on coverslips were fixed with 1% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed with PBS containing 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBST) and stained for 1 h with 5 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 in PBST, followed by rinsing with PBST. Cells were then stained for TRAP as we outlined using a kit from Sigma according to the provider’s instructions (34). Coverslips were mounted on slides and visualized using light and epifluorescence. TRAP-positive cells containing at least three nuclei were scored as osteoclasts. Apoptotic osteoclasts were delineated on the basis of chromatin condensation as we reported (34).

Western blotting

Osteoclasts were treated as outlined (see legend for Fig. 6A). At the end of treatments, cells were placed on ice and rinsed three times with cold PBS for analysis by Western blotting. Protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad’s protein quantitation in detergent analysis kit. Forty micrograms of protein per lane were used for analysis. Western blotting was carried out as previously outlined (34). Antiphospho- and total antibodies directed toward MEK 1/2 (Ser217/221), ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), AKT (Ser473), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (Ser536), STAT3 (Tyr705), and STAT3 (Ser727) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) were used according to the product directions as we reported (34). Antitubulin hybridoma supernatant (E7) was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA).

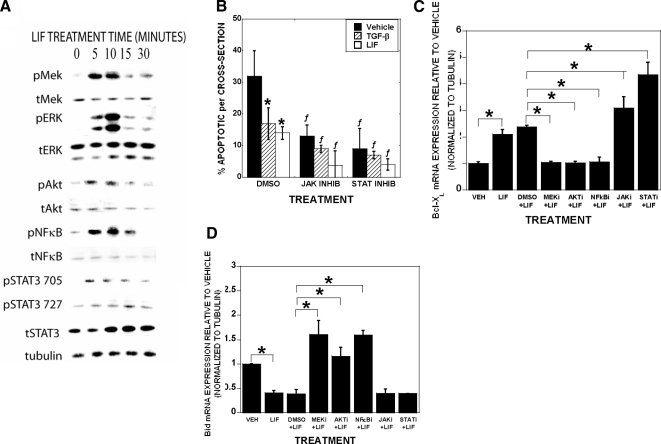

Figure 6.

LIF stimulates activation of osteoclast signaling to modulate BclXL and Bid expression. A, Osteoclasts were serum starved for 1 h before 50 ng/ml LIF addition for 0, 5, 10, 15, or 30 min. Cells were examined by Western blotting. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. B, Mature osteoclasts were pretreated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the JAK inhibitor AG-490 (10 μm), or the JAK/STAT inhibitor WP-1034 (STATi; 6 μm) as indicated for 1 h. Vehicle (VEH), 2 ng/ml TGF-β, or 50 ng/ml LIF were added for 8 h before fixing and analyzed for apoptosis as above. Data are the mean of six replicates. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment; ƒ, P < 0.05 compared with DMSO treatment. C and D, Mature osteoclasts were pretreated with DMSO, the MEK inhibitor UO126 (10 μm), the AKT inhibitor AKT IV (1 μm), the NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolinedithio carbamate (PDTC), AG-490 (JAKi), or WP-1034 (STATi) as indicated for 1 h. BSA (VEH) or 50 ng/ml LIF were added to the indicated samples for 60 min. RNA was harvested and analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Osteoclasts were treated as detailed in the figure legends. Cells were rinsed with PBS and RNA harvested using Trizol reagent according to the product literature (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After quantitation, cDNA was synthesized and real-time PCR analysis carried out as we have reported (9).

Primers for real-time PCR analysis

Gene sense and antisense primers, respectively, were: Bcl-XL, 5′-GATGGAGGAACCAGGTTGTG-3′ and 5′-CCCCGGAAGGTCTTTTGTAT-3′; Bcl-2, 5′-CGGGAGATCGTGATGAAGTACA-3′ and 5′-ATCTCCAGCATCCCACTCGTA-3′; Mcl-1, 5′-GTGCTTGACAAAGTCCCAAGTG-3′ and 5′-TCATCCAAACCAAGCCAAAGT-3′; Bid, 5′-CCATGTAGGTGGGCTTCTGT-3′ and 5′-GATCAGCCATTCGGCTTTTA-3′; Bcl-W, 5′-GCCCTCAAACAGAACAGCTC-3′ and 5′-TGGGAAGGGTAGAGCAGAGA-3′; Bad, 5′-GCAGGCACTGCAACACAGAT-3′ and 5′-TCCCACCAGGACTGGATAATG-3′; Bak, 5′-TGATATTAACCGGCGCTACGA-3′ and 5′-GCTGTGGGCTGAAGCTGTTC-3′; Bax, 5′-CGGCGAATTGGAGATGAACT-3′ and 5′-GTCCACGTCAGCAATCATCCT-3′; Bim, 5′-CGGAGACGAGTTCAACGAAACT-3′ and 5′-CAGCCTCGCGGTAATCATTT-3′; LIF, 5′-CCATCATCTGGTCCTTTGCT-3′ and 5′-GATCCCAGTCCCCTTAGCTC-3′; SOCS3, 5′-GCTGGCCAAAGAAATAACCA-3′ and 5′-GCCTGGCACCAGTATAGCTC-3′; and tubulin, 5′-CTGCTCATCAGCAAGATCAGAG-3′ and 5′-GCATTATAGGGCTCCACCACAG-3′.

LIF protein ELISA

Osteoclasts were treated with vehicle or LIF for 8 or 24 h before conditioned media harvest. The media were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min to remove cellular debris and assessed for LIF protein by ELISA (mouse LIF Quantikine ELISA kit; R&D Systems) according to directions.

Reporter assay

Adenovirus expressing the LIF promoter driving luciferase gene expression (35) was generated by contract with Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA). The adenovirus expressing the SOCS3 promoter driving luciferase gene expression was generated by Vector Biolabs from DNA that was a gift from Dr. E. N. Benveniste (Department of Cell Biology, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL). These were used to infect cells at a multiplicity of infection of 100 and treated as detailed in the figure legends. Cell lysates were harvested and processed as described (36). Protein concentrations were determined as above, and 75 μg in 20 μl were used to measure luciferase activity as described (36).

Antibody, adenoviral, chemical, and small interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibition

Antibodies were added to cultures once the osteoclasts were mature, as detailed (see legend of Fig. 3). Adenoviruses to deliver dominant-negative AKT and mutant IκB were purchased from Vector BioLabs. The adenovirus to deliver dominant-negative SMAD3 was the kind gift of Dr. Rosa Sera (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL). All adenoviruses were delivered at a multiplicity of infection of 100 as detailed in the figure legends. Chemical inhibitors were added to cultures 1 h before treatments as detailed in the figure legends. Accell siRNA, nontargeting RNA controls, and 5× siRNA buffer were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). A stock 100 μm siRNA was prepared in 1× siRNA buffer. One tenth volume of the siRNA or control was combined with reduced serum (2%) media with 25 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor and 100 ng/ml RANKL and added to osteoclast precursors on d 3 of culture. Cultures were maintained for 40 h before 8 h of treatment with vehicle, TGF-β, or LIF.

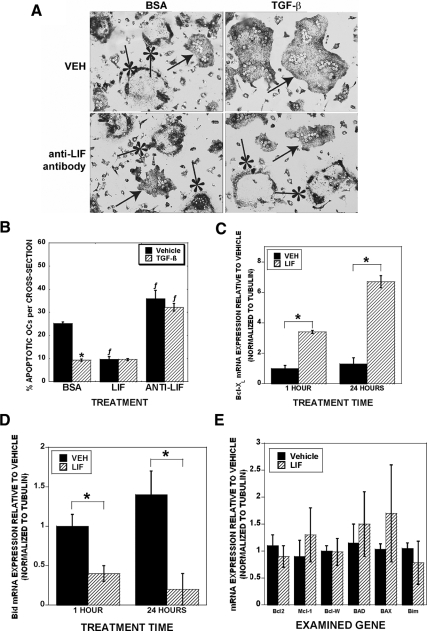

Figure 3.

LIF mediates TGF-β support of osteoclast survival and regulates BclXL and Bid expression. A, Osteoclasts were treated with vehicle (BSA), 2 ng/ml TGF-β, or 0.1 μg/ml anti-LIF blocking antibody for 8 h. Cells were analyzed for apoptosis by analysis of chromatin condensation. Arrows indicate viable osteoclasts, and asterisks indicate apoptotic osteoclasts with condensed chromatin. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. B, Quantitation of osteoclasts pictured in A. Cultures that were treated with BSA or TGF-β, 50 ng/ml LIF or anti-LIF blocking antibody for 8 h. Data are the mean of six replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse. The experiment was repeated four times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment; ƒ, P < 0.05 compared with BSA treatment. C–E, Mature osteoclasts were treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml LIF before RNA harvest and real-time PCR analysis. Data in E are for 1 h treatment. Results of 24 h treatment were similar. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Statistics

Details of replicate in each experiments and the number of repeat experiments are in the figure legends. Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA compared with controls and are presented as mean ± sem. Significance was determined at P < 0.05 using KaleidaGraph software (Reading, PA).

Results

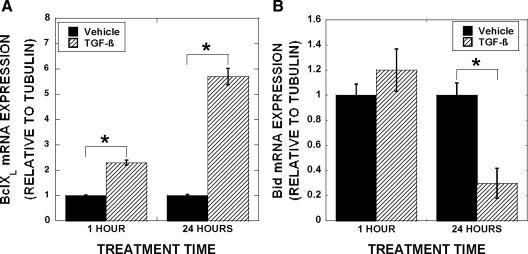

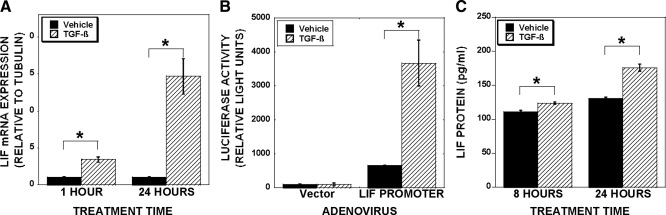

We documented that TGF-β treatment of mature osteoclast leads to rapid stimulation of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 in the absence of influences on proapoptotic family members (12). We hypothesize that TGF-β influences on osteoclast may include indirect modulation of Bcl2 family members with prolonged exposure. We therefore examined gene expression changes after 1 and 24 h of TGF-β treatment (Fig. 1). Bcl-XL was rapidly induced and longer-term TGF-β treatment further increased expression (Fig. 1A). Examination of proapoptotic Bid expression revealed that there was a delayed repression, which is consistent with the hypothesis that TGF-β regulation of Bid requires induction of a mediator (Fig. 1B). We reasoned that sustained Bcl-XL induction may be due to TGF-β and/or a downstream effecter-mediated stimulation, whereas delayed suppression of Bid most likely is due to influences of a mediating factor. We therefore sought to uncover the mediator of Bid suppression and whether the augmented Bcl-XL expression was due to this same mediator. Because LIF promotes survival of other cell types, we determined whether TGF-β modulates LIF expression. We examined responses of osteoclasts treated for 1 or 24 h with vehicle or TGF-β and identified LIF as a candidate TGF-β response factor (Fig. 2A). LIF expression was induced within 1 h of TGF-β treatment, and expression induction was sustained through 24 h of treatment. As documented in Fig. 2B, TGF-β activates the LIF promoter in mature osteoclasts, further supporting TGF-β induction of LIF. We next assessed the effects of TGF-β treatment on production and secretion of LIF protein. As shown in Fig. 2C, within 8 h, there was a small, but significant, increase in secreted LIF protein with TGF-β treatment and TGF-β-mediated LIF secretion increased through 24 h of culture.

Figure 1.

Influences of TGF-β treatment on Bcl-2 family member expression. Mature osteoclasts were treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 1 or 24 h before harvest and real-time PCR analysis for BclXL (A) and Bid (B). Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated four times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

TGF-β stimulates LIF expression. A, Osteoclasts were treated with vehicle or 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 1 or 24 h. RNA was analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated four times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05. B, Osteoclasts were adenovirally infected with empty vector or a construct composed of 274 bp upstream of the LIF start site linked to a luciferase reporter. After 24 h, osteoclasts were treated with TGF-β for 2 d before lysis, normalization for protein levels, and luciferase assay. *, P < 0.05. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. C, Osteoclasts were treated for 8 or 24 h with vehicle or 2 ng/ml TGF-β and the conditioned media collected. LIF protein was assayed using R&D’s mouse LIF Quantikine kit. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments *, P < 0.05.

Because osteoclasts secreted LIF, which is known to have prosurvival effects, and TGF-β increased LIF expression, we examined whether LIF expression contributed to TGF-β-mediated support of osteoclast survival (Fig. 3). Figure 3A has representative images of the cultures that are quantitated in Fig. 3B. Addition of recombinant mouse LIF reduced osteoclast apoptosis in vehicle-treated cultures to the same level as TGF-β-treated cultures. Interestingly, cotreatment with LIF and TGF-β did not further reduce apoptosis beyond either treatment alone. We used LIF-blocking antibodies to block LIF binding to its receptor complex and observed that apoptosis with vehicle treatment in the presence of the antibodies was increased significantly compared with BSA treatment. Addition of TGF-β did not suppress apoptosis in cultures that contained the LIF blocking antibodies. There was no significant influence on an isotype-matched control antibody on survival (data not shown). Taken together, these data support that TGF-β support of osteoclast survival requires LIF activity. To determine the mechanisms by which LIF suppresses osteoclast apoptosis, we examined LIF influences on mature osteoclast Bcl2 family member gene expression. Within 1 h of LIF treatment, mature osteoclasts Bcl-XL message levels increased and Bid message levels decreased (Figs. 3, B and D). The response was sustained through at least 24 h of treatment. We were unable to detect changes in prosurvival Bcl-2, Mcl-1, or Bcl-W or proapoptotic BAD, Bik, Bax, or Bim (Fig. 3E).

LIF influences can be either prosurvival or proapoptotic, depending on SOCS3 expression (31). In these studies, SOCS3 promoted prosurvival responses at the expense of proapoptotic responses. Because the level of LIF protein secretion induction was modestly elevated in comparison with basal LIF protein secretion levels, we examined TGF-β influences on SOCS3 expression to resolve whether elevation of SOCS3 could contribute to osteoclast LIF prosurvival signaling. We observed rapid and sustained increased SOCS3 expression after TGF-β treatment of osteoclasts (Fig. 4A). LIF had a slight effect on SOCS3 expression that did not reach statistical significance until 24 h of LIF treatment. TGF-β treatment activated a SOCS3 promoter-driven reporter construct (Fig. 4B). To determine the influence of SOCS3 expression on osteoclast survival, we used targeted siRNA. siRNA-targeting SOCS3 suppressed SOCS3 protein levels by 47% and abrogated TGF-β and LIF support of osteoclast survival (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, SOCS3 suppression significantly increased osteoclast apoptosis in LIF-treated cultures. To further explore this, we examined the impact of small interfering SOCS3 on Bcl-2 family members (Fig. 4D). Expression of none of the family members we examined was significantly altered when SOCS3 expression was reduced.

Figure 4.

TGF-β induces SOCS3 to promote osteoclast survival. A, Osteoclasts were treated with vehicle or 2 ng/ml TGF-β, or 50 ng/ml LIF for 1 or 24 h. RNA was harvested, processed, and analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05. B, Osteoclasts were adenovirally infected with empty vector or a construct composed of 940 bp upstream of the SOCS3 start site linked to a luciferase reporter. After 24 h, osteoclasts were treated with TGF-β for 2 d before lysis, normalization for protein levels, and luciferase assay. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from two mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05. C, Osteoclasts were treated with siRNA as indicated for 40 h before vehicle, 2 ng/ml TGF-β, or 50 ng/ml LIF treatment for 8 h. Cells were fixed and analyzed for apoptosis as above. Data are the mean of six replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment; ƒ, P < 0.05 compared with nontargeting siRNA treatment. D, Osteoclasts were treated as in C with nontargeting or siRNA targeting SOCS3 before LIF treatment. RNA was harvested in triplicate replicates from a single marrow preparation from one mouse for real-time PCR analysis. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments.

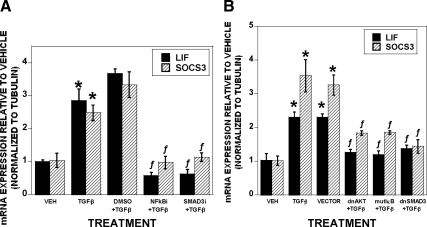

Next, we investigated the mechanisms by which TGF-β stimulates LIF and SOCS3 expression. We have shown that TGF-β increases nuclear localization of SMAD3 and NF-κB, and we therefore examined whether activation of these transcription factors was involved in TGF-β influences on LIF and SOCS3 expression (12). Pharmacological inhibition of SMAD3 or NF-κB blocks TGF-β-mediated induction of LIF and SOCS3 (Fig. 5A). To further explore these responses, we used dominant-negative adenoviruses to block AKT/NF-κB and SMAD3 signaling and confirmed that AKT/NF-κB and SMAD signaling are involved in TGF-β-mediated stimulation of LIF and SOCS3 expression (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

TGF-β stimulates LIF and SOCS3 expression via NF-κB and SMAD. A, Mature osteoclasts were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolinedithio carbamate (PDTC) (25 μm), or specific inhibitor of Smad3 (SIS3) (20 μm) for 1 h before treatment. B, Mature osteoclasts were infected with the indicated adenovirus 20 h before treatment. A and B, Vehicle or 2 ng/ml TGF-β were added to the indicated samples for an additional 1 h. RNA was harvested and analyzed by real-time PCR for LIF and SOCS3 expression. *, P < 0.05 to vehicle treatment; ƒ, <0.05 to DMSO (A) or vector (B) treatment. Data are the mean of three replicates from a single marrow preparation from three mice. The experiment was repeated three times with separate mice and these results are representative of these experiments.

To resolve the mechanism by which LIF modulates Bcl-XL and Bid, we examined LIF influences on the known LIF signaling pathways in mature osteoclasts. As shown in Fig. 6A, LIF treatment induced rapid and transient phosphorylation of MEK, ERK, AKT, and NF-κB. We observed rapid increased transient STAT3 phosphorylation at 705, whereas phosphorylation at 727 was delayed. JAK/STAT inhibition reduced apoptosis in vehicle, TGF-β, and LIF-treated cultures (Fig. 6B). We examined the influences of blocking LIF-mediated activation of MEK, AKT, NF-κB, JAK, and STAT signaling (Fig. 6, C and D). Blocking MEK, AKT, or NF-κB reduced LIF-mediated induction of Bcl-XL and suppression of Bid. Blocking either JAK or STAT during LIF treatment led to increased Bcl-XL expression, although these inhibitors had no impact on Bid expression.

Discussion

Our data document that there is rapid and sustained increased LIF expression after TGF-β treatment of osteoclasts and that LIF is required for TGF-β support of osteoclast survival. The levels of LIF detected in the conditioned media were in the picogram per milliliter range, whereas the level of exogenous LIF that we added was 50 ng/ml. Initial consideration of these data raised the conjecture that LIF protein level changes in response to TGF-β may be too small to be biologically significant. More careful consideration of the logistics of cell culture in light of our data that blocking LIF blocked TGF-β-mediated promotion of survival caused us to reconsider this. When conditioned media are collected, it represents a pool of media in close proximity to the cells as well as the rest of the media distant from the cells. Because the osteoclasts are secreting LIF, its concentration in proximity to the cell surface LIF receptor will be manyfold higher than that of the overall diluted media in the culture well. Moreover, any LIF that had bound to its receptor complex on secretion would have been internalized and degraded, removing it from availability for this assay.

We examined TGF-β effects on SOCS3 expression because it has been shown to suppress LIF-STAT signaling to promote survival. We examined LIF signaling to determine whether STAT signaling is activated by LIF in osteoclasts. LIF treatment of osteoclasts activated MEK/ERK, AKT/NF-κB, and STAT3 signaling pathways. We next examined SOCS3 expression and found that TGF-β increases expression of osteoclast SOCS3. Lu et al. (31) documented that mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking SOCS3 responded to LIF treatment with increased apoptosis, whereas wild-type MEFs responded with increased survival. In wild-type MEFs, LIF caused transient STAT3 activation and increased AKT activation in a pattern similar to the transient STAT3 activation reported here. Comparisons of signaling differences between wild-type and SOCS3−/− MEFs revealed that the loss of SOCS3 caused enhanced and sustained STAT3 activation and repressed AKT activation in the SOCS3−/− MEFs, as contrasted to the wild-type MEFs. Because blocking SOCS3 blocked survival responses in osteoclasts, this supports that TGF-β-mediated induction of SOCS3 is required for LIF to promote osteoclast survival. Blocking SOCS3 enhanced apoptosis in the presence of LIF, indicating that LIF also has proapoptotic effects in the absence of SOCS3. These data support that LIF signaling in osteoclasts can be prosurvival or proapoptotic, depending on whether SOCS3 is expressed, which is consistent with the above observations in MEFs. We eliminated several Bcl-2 family members as targets for expression changes when SOCS3 is suppressed. There was a relative minor and delayed induction of SOCS3 by LIF. This, in conjunction with the robust promoter activation by TGF-β, indicates that TGF-β is the more dominant factor in directly stimulating SOCS3 expression to promote LIF survival responses in osteoclasts. Thus, survival requires the coordinate activation of LIF and SOCS3 by TGF-β in osteoclasts.

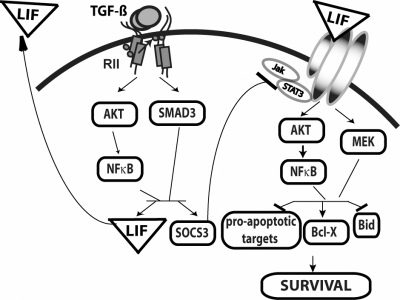

Interrogation of the mechanisms by which LIF promotes osteoclast survival revealed rapid induction of prosurvival Bcl-XL and repression of proapoptotic Bid. LIF induction of Bcl-XL involves coordinate activation of MEK/AKT/NF-κB signaling. Suppressing JAK/STAT signaling during LIF treatment further increased Bcl-XL expression, indicating a role for JAK/STAT signaling in partial suppression of LIF-mediated increased Bcl-XL expression. Because SOCS3 represses JAK/STAT signaling, one contribution of TGF-β to osteoclast survival is to induce SOCS3 to repress JAK/STAT-mediated suppression of Bcl-XL expression. The slight stimulation of Bcl-XL expression observed in cultures with suppressed SOCS3 expression suggests that prosurvival factors other than Bid may be enhanced by SOCS3, most likely by blocking proapoptotic JAK/STAT targets. Thus, our data support that TGF-β induces LIF, which induces prosurvival Bcl-XL through activation of prosurvival MEK/ERK and AKT/NF-κB activation and suppresses antisurvival JAK/STAT signaling because of SOCS3 induction. LIF-mediated Bid repression involves MEK/AKT/NF-κB signaling with no apparent involvement of JAK/STAT signaling. Figure 7 is a model of this proposed survival mechanism.

Figure 7.

Model of TGF-β influences on osteoclast survival. TGF-β binding to its receptor complexes (RII) activates SMAD and AKT/NF-κB signaling to increase LIF and SOCS3 expression. LIF protein is secreted, binding to its receptor. SOCS3 suppresses JAK/STAT signaling to reduce proapoptotic responses including suppression of Bcl-XL, whereas LIF activates prosurvival AKT/NF-κB and MEK signaling to increase Bcl-XL and suppress Bid expression.

A recent study of LIF knockout mice revealed impacts on offspring when homozygous null mice are bred together (37). The bones of the neonatal offspring contain very large osteoclasts due to placental defects that cause hypoxia during fetal development. More relevant to the study reported here, osteoclast progenitors from the livers of the knockout fetuses do not differentiate well in vitro due to increased precursor apoptosis. Addition of LIF during the in vitro cultures reversed this, supporting that autocrine LIF suppresses osteoclast precursor apoptosis, enabling osteoclast progenitors to differentiate. Thus, the combination of the data from this and our studies reported here implicate LIF in survival of osteoclast progenitors (37) and mature osteoclasts (this study).

Among the pleiotropic influences of TGF-β, it functions as a tumor suppressor by suppressing proliferation and promoting apoptosis of multiple cell types (38). In contrast, in late stages of tumor development, TGF-β becomes oncogenic as it promotes proliferation and tumor cell survival (38,39,40). Recently it was found that TGF-β induces LIF expression in glioblastoma cells, supporting that at least part of its oncogenic capacity may be due to up-regulation of this prosurvival cytokine (41). To our knowledge, the data reported here is the first demonstration that TGF-β induces LIF in nontransformed cells.

In oocytes, LIF alone has little impact on survival but synergizes with stem cell factor to promote survival (42). Similarly, LIF, in conjunction with bone morphogenic protein 2 promotes cardiomyocyte survival by synergistic activation of MEK/ERK (43). Fujio et al. (44) documented LIF-mediated increased Bcl-XL expression in cardiomyocytes through activation of STAT1 and LIF induces motoneuron Bcl-XL expression via activation of STAT3 (45). These studies are in contrast to our observation that blocking JAK/STAT signaling enhanced Bcl-XL expression. These data indicate that STAT influences on Bcl-XL are cell type specific. Although reports have shown that neuronal survival responses involve LIF-mediated transient activation of the JAK/STAT pathway, other reports documented that LIF promotes neuronal and oligodendrocyte survival through activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (29,30,46,47,48,49,50,51). Our studies reveal that LIF promotes osteoclast survival by activation of MEK and AKT/NF-κB pathways to overcome JAK/STAT-mediated repression of Bcl-XL.

The Bcl2 family contains multiple prosurvival and proapoptotic family members that govern mitochondria membrane permeability and caspase activation. The ratio of prosurvival to proapoptotic family members determines whether a cell enters apoptosis. Members of the Bcl2 family share one or more domains of high homology, called the Bcl2 homology (BH) domains, which are required for family member functions. Bcl-XL contains BH1, BH2, BH3, and BH4 domains and binds to BH3 domain-containing proapoptotic family members including Bid. Bcl-XL binding to Bid prevents Bid-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (52). Our discovery that LIF stimulates prosurvival Bcl-XL and inhibits proapoptotic Bid reveals a pivotal mechanism by which LIF promotes osteoclast survival. This may be crucial in the sustained resorption that takes place during conditions of excessive bone loss such as tumor-driven osteolysis or postmenopausal osteoporosis.

TGF-β is released from the bone by osteoclastic activity, and we have shown that osteoclasts synthesize and activate TGF-β (53). Because of this, active TGF-β levels are relatively high during periods of high bone turnover. If elevated levels of TGF-β promoted osteoclast apoptosis, the expectation would be that there would be significant osteoclast apoptosis during periods of high bone turnover, which has never been reported. In fact, apoptosis of resorbing osteoclasts would provide negative feedback to repress resorption, which has also never been documented. Accordingly, our observations are in concert with the studies of Mohammad et al. (10) that blocking TGF-β in vivo decreases bone loss at least in part through repression of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Our data, in conjunction with our documentation of biphasic effects of TGF-β on osteoclast differentiation (9), support that TGF-β levels have complex roles in regulating bone resorption. Under conditions of low bone resorption, when TGF-β concentrations are relatively low, TGF-β stimulates osteoclast differentiation. During periods of high bone resorption levels, the resultant higher TGF-β levels repress both differentiation and mature osteoclast apoptosis, increasing the half-life of resident osteoclasts and sustaining high bone resorption despite suppression of osteoclast differentiation. Consequently, understanding the mechanisms by which TGF-β supports osteoclast survival may provide new directions for effective therapies to reduce bone loss with aging and under pathological conditions such as osteolysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DE14680 (to M.J.O.) and the Mayo Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflict of interests.

First Published Online February 24, 2010

Abbreviations: BH, Bcl2 homology; Bid, Bcl-2 interacting domain; JAK, Janus kinase; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; MEK, MAPK kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; PBST, PBS containing Tween 20; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SMAD, phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic; SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

References

- Guise TA, Mundy GR 1998 Cancer and bone. Endocr Rev 19:18–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michigami T, Ihara-Watanabe M, Yamazaki M, Ozono K 2001 Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) is a key molecule of osteoclast formation for bone metastasis in a newly developed model of human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 61:1637–1644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman GD 1995 Osteoclast function in Paget’s disease and multiple myeloma. Bone 17:57S–61S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winding B, Misander H, Sveigaard C, Therkildsen B, Jakobsen M, Overgaard T, Oursler MJ, Foged NT 2000 Human breast cancer cells induced angiogenesis, recruitment, and activation of osteoclasts in osteolytic metastasis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 126:631–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goltzman D 2001 Osteolysis and cancer. J Clin Invest 107:1219–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens K, ten Dijke P, Janssens S, Van Hul W 2005 Transforming growth factor-β1 to the bone. Endocr Rev 26:743–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan RA, Kanaan LA 2006 Transforming growth factor β1, bone connection. Med Sci Monit 12:RA164–RA169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SW, Evans KE, Lovibond AC 2008 Transforming growth factor-β enables NFATc1 expression during osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 366:123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst M, Gorny G, Galvin RJ, Oursler MJ 2004 Roles of stromal cell RANKL, OPG, and M-CSF expression in biphasic TGF-β regulation of osteoclast differentiation. J Cell Physiol 200:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad KS, Chen CG, Balooch G, Stebbins E, McKenna CR, Davis H, Niewolna M, Peng XH, Nguyen DH, Ionova-Martin SS, Bracey JW, Hogue WR, Wong DH, Ritchie RO, Suva LJ, Derynck R, Guise TA, Alliston T 2009 Pharmacologic inhibition of the TGF-β type I receptor kinase has anabolic and anti-catabolic effects on bone. PLoS ONE 4:e5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futakuchi M, Nannuru KC, Varney ML, Sadanandam A, Nakao K, Asai K, Shirai T, Sato SY, Singh RK 2009 Transforming growth factor-β signaling at the tumor-bone interface promotes mammary tumor growth and osteoclast activation. Cancer Sci 100:71–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingery A, Bradley EW, Pederson L, Ruan M, Horwood NJ, Oursler MJ 2008 TGF-β coordinately activates TAK1/MEK/AKT/NFκB and SMAD pathways to promote osteoclast survival. Exp Cell Res 314:2725–2738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Massagué J 2003 Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113:685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XH, Derynck R 2005 Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21:659–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH 2005 Non-Smad TGF-β signals. J Cell Sci 118:3573–3584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE 2003 Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature 425:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borton AJ, Frederick JP, Datto MB, Wang XF, Weinstein RS 2001 The loss of Smad3 results in a lower rate of bone formation and osteopenia through dysregulation of osteoblast differentiation and apoptosis. J Bone Miner Res 16:1754–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auernhammer CJ, Melmed S 2000 Leukemia-inhibitory factor-neuroimmune modulator of endocrine function. Endocr Rev 21:313–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derigs HG, Boswell HS 1993 LIF mRNA expression is transcriptionally regulated in murine bone marrow stromal cells. Leukemia 7:630–634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JA, Waring PM, Filonzi EL 1993 Induction of leukemia inhibitory factor in human synovial fibroblasts by IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol 150:1496–1502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IK, Waring P, Novak U, Hamilton JA 1993 Production of leukemia inhibitory factor by human articular chondrocytes and cartilage in response to interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor α. Arthritis Rheum 36:790–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JA, Zheng T, Whiting NL, Marcovici A, Trow TK 1994 Cytokine-cytokine synergy and protein kinase C in the regulation of lung fibroblast leukemia inhibitory factor. Am J Physiol 266:L426–L435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset C, Jazwiec B, Taupin JL, Liu H, Richard S, Mahon FX, Reiffers J, Moreau JF, Ripoche J 1995 In vitro biosynthesis of leukemia inhibitory factor/human interleukin for DA cells by human endothelial cells: differential regulation by interleukin-1α and glucocorticoids. Blood 86:3763–3770 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CD, Bai Y, Ding M, Jonakait GM, Hart RP 1996 Interleukin-1 involvement in the induction of leukemia inhibitory factor mRNA expression following axotomy of sympathetic ganglia. J Neuroimmunol 70:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabaud M, Fossiez F, Taupin JL, Miossec P 1998 Enhancing effect of IL-17 on IL-1-induced IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes and its regulation by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol 161:409–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DA 1995 Leukaemia inhibitory factor expression in cultured rat anterior pituitary is regulated by glucocorticoids. J Neuroendocrinol 7:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset C, Taupin JL, Lemercier C, Moreau JF, Reiffers J, Ripoche J 1999 Leukaemia inhibitory factor expression is inhibited by glucocorticoids through post-transcriptional mechanisms. Cytokine 11:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JI, Strock CJ, Ball DW, Nelkin BD 2003 The Ras/Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway induces autocrine-paracrine growth inhibition via the leukemia inhibitory factor/JAK/STAT pathway. Mol Cell Biol 23:543–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C, Liu BQ, Kim SY, Kim EJ, Park YJ, Yoo JY, Han HS, Bae YC, Ronnett GV 2009 Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes olfactory sensory neuronal survival via phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway activation and Bcl-2. J Neurosci Res 87:1098–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaets H, Dumont D, Vanderlocht J, Noben JP, Leprince P, Robben J, Hendriks J, Stinissen P, Hellings N 2008 Leukemia inhibitory factor induces an antiapoptotic response in oligodendrocytes through Akt-phosphorylation and up-regulation of 14-3-3. Proteomics 8:1237–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Fukuyama S, Yoshida R, Kobayashi T, Saeki K, Shiraishi H, Yoshimura A, Takaesu G 2006 Loss of SOCS3 gene expression converts STAT3 function from anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic. J Biol Chem 281:36683–36690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abell K, Bilancio A, Clarkson RW, Tiffen PG, Altaparmakov AI, Burdon TG, Asano T, Vanhaesebroeck B, Watson CJ 2005 Stat3-induced apoptosis requires a molecular switch in PI(3)K subunit composition. Nat Cell Biol 7:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abell K, Watson CJ 2005 The Jak/Stat pathway: a novel way to regulate PI3K activity. Cell Cycle 4:897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingery A, Bradley E, Shaw A, Oursler MJ 2003 Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase coordinately activates the MEK/ERK and AKT/NFκB pathways to maintain osteoclast survival. J Cell Biochem 89:165–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger AM, Erdmann I, Bamberger CM, Jenatschke SS, Schulte HM 1997 Transcriptional regulation of the human ‘leukemia inhibitory factor’ gene: modulation by glucocorticoids and estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol 127:71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen SA, Subramaniam M, Janknecht R, Spelsberg TC 2002 TGFβ inducible early gene enhances TGFβ/Smad-dependent transcriptional responses. Oncogene 21:5783–5790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozec A, Bakiri L, Hoebertz A, Eferl R, Schilling AF, Komnenovic V, Scheuch H, Priemel M, Stewart CL, Amling M, Wagner EF 2008 Osteoclast size is controlled by Fra-2 through LIF/LIF-receptor signalling and hypoxia. Nature 454:221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover DG, Bierie B, Moses HL 2007 A delicate balance: TGF-β and the tumor microenvironment. J Cell Biochem 101:851–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentzsch S, Chatterjee M, Gries M, Bommert K, Gollasch H, Dörken B, Bargou RC 2004 PI3-K/AKT/FKHR and MAPK signaling cascades are redundantly stimulated by a variety of cytokines and contribute independently to proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 18:1883–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Morita E, Mihara S, Kanno M, Yamamoto S 2001 Identification of leukemia inhibitory factor as a potent mast cell growth-enhancing factor produced by mouse keratinocyte cell line, KCMH-1. Arch Dermatol Res 293:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñuelas S, Anido J, Prieto-Sánchez RM, Folch G, Barba I, Cuartas I, García-Dorado D, Poca MA, Sahuquillo J, Baselga J, Seoane J 2009 TGF-β increases glioma-initiating cell self-renewal through the induction of LIF in human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 15:315–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Manganaro TF, Tao XJ, Martimbeau S, Donahoe PK, Tilly JL 1999 Requirement for phosphatidylinositol-3′-kinase in cytokine-mediated germ cell survival during fetal oogenesis in the mouse. Endocrinology 140:941–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Masaki M, Hiramoto Y, Sugiyama S, Kuroda T, Terai K, Hori M, Kawase I, Hirota H 2006 Cross-talk between bone morphogenetic protein 2 and leukemia inhibitory factor through ERK 1/2 and Smad1 in protection against doxorubicin-induced injury of cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40:224–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio Y, Kunisada K, Hirota H, Yamauchi-Takihara K, Kishimoto T 1997 Signals through gp130 upregulate bcl-x gene expression via STAT1-binding cis-element in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest 99:2898–2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer U, Gunnersen J, Karch C, Wiese S, Holtmann B, Takeda K, Akira S, Sendtner M 2002 Conditional gene ablation of Stat3 reveals differential signaling requirements for survival of motoneurons during development and after nerve injury in the adult. J Cell Biol 156:287–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema SS, Richards L, Murphy M, Bartlett PF 1994 Leukemia inhibitory factor prevents the death of axotomised sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia of the neonatal rat. J Neurosci Res 37:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema SS, Richards LJ, Murphy M, Bartlett PF 1994 Leukaemia inhibitory factor rescues motoneurones from axotomy-induced cell death. Neuroreport 5:989–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurek JB, Bennett TM, Bower JJ, Muldoon CM, Austin L 1998 Leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) production in a mouse model of spinal trauma. Neurosci Lett 249:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Reid K, Brown MA, Bartlett PF 1993 Involvement of leukemia inhibitory factor and nerve growth factor in the development of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Development 117:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberle S, Schober A, Meyer V, Holtmann B, Henderson C, Sendtner M, Unsicker K 2006 Loss of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor β or cardiotrophin-1 causes similar deficits in preganglionic sympathetic neurons and adrenal medulla. J Neurosci 26:1823–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlon DS, Ketels KV, Coulson MT, Williams T, Grover M, Edpao W, Richter CP 2006 Survival and morphology of auditory neurons in dissociated cultures of newborn mouse spiral ganglion. Neuroscience 138:653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse NJ, Sedelies KA, Trapani JA 2006 Role of Bid-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization in granzyme B-induced apoptosis. Immunol Cell Biol 84:72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oursler MJ 1994 Osteoclast synthesis and secretion and activation of latent transforming growth factor β. J Bone Miner Res 9:443–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]