Abstract

Reduction of food intake and body weight by leptin is attributed largely to its action in the hypothalamus. However, the signaling splice variant of the leptin receptor, LRb, also is expressed in the hindbrain, and leptin injections into the fourth cerebral ventricle or dorsal vagal complex are associated with reductions of feeding and body weight comparable to those induced by forebrain leptin administration. Although these observations suggest direct hindbrain action of leptin on feeding and body weight, the possibility that hindbrain leptin administration also activates the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling in the hypothalamus has not been investigated. Confirming earlier work, we found that leptin produced comparable reductions of feeding and body weight when injected into the lateral ventricle or the fourth ventricle. We also found that lateral and fourth ventricle leptin injections produced comparable increases of STAT3 phosphorylation in both the hindbrain and the hypothalamus. Moreover, injection of 50 ng of leptin directly into the nucleus of the solitary tract also increased STAT3 phosphorylation in the hypothalamic arcuate and ventromedial nuclei. Increased hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation was not due to elevation of blood leptin concentrations and the pattern of STAT3 phosphorylation did not overlap distribution of the retrograde tracer, fluorogold, injected via the same cannula. Our observations indicate that even small leptin doses administered to the hindbrain can trigger leptin-related signaling in the forebrain, and raise the possibility that STAT3 phosphorylation in the hypothalamus may contribute to behavioral and metabolic changes observed after hindbrain leptin injections.

Phosphorylation of hypothalamic STAT3 following hindbrain leptin injection suggests that neurons remote from a hindbrain injection site might contribute to integrated behavioral and metabolic responses to local leptin applications.

Leptin, a 16-kDa cytokine hormone encoded by the ob gene (1,2,3) and secreted primarily by white adipocytes, appears to be important to control of food intake and body weight (4,5,6,7). Although most experimental attention regarding control of food intake and body weight by leptin has focused on the hypothalamus, leptin receptor (LRb) protein and mRNA are expressed by neurons in brain areas outside the hypothalamus (8,9,10,11). Furthermore, reports of reduced feeding and body weight loss after leptin injections into areas remote from the hypothalamus (10,11,12) suggest that other brain areas contribute to leptin’s control of food intake and body weight. In this regard, the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the hindbrain, an area known for its role in integration of visceral afferent information and control of food intake, is of particular interest. Leptin injections into the fourth cerebral ventricle or directly into the NTS reduce food intake and body weight to a degree comparable to third or lateral ventricle leptin injection (10). Furthermore, systemic injection of leptin is associated with phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in neurons of the NTS (13,14). These results and others suggest that reduction of food intake and body weight associated with hindbrain leptin application is the result of leptin’s direct activation of hindbrain neurons, independent of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus. Despite these compelling observations, there are no published studies examining leptin signaling in the hypothalamus after hindbrain leptin application.

Leptin’s control of food intake and body weight is mediated, at least in part, by activation of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and phosphorylation of STAT3 (15,16,17). Moreover, systemic or third ventricle injections of leptin that result in reduced food intake and body fat loss also are associated with increased STAT3 phosphorylation in the hypothalamus, including the arcuate (ARC), ventromedial hypothalamic (VMH), and dorsomedial hypothalamic (DMH) nuclei (18,19,20,21,22,23), where the long form of the LRb is abundantly expressed (24,25). In the experiments reported here, we confirmed the results of Grill et al. (10) that lateral ventricle (LV) and fourth ventricle (4V) leptin injections produced comparable reductions of food intake and body weight. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that hindbrain leptin injection might activate the JAK/STAT3 signaling cascade in the basomedial hypothalamus, remote to the actual site of leptin injection.

We found that hindbrain leptin injection is associated with a similar increase in STAT3 phosphorylation in both the hypothalamus and the hindbrain. The mechanisms by which hindbrain leptin triggers hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation remain uncertain. Nevertheless, our observations raise the possibility that activation of hypothalamic neurons might contribute to behavioral and metabolic responses after hindbrain leptin injection.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy, CA) were housed in suspended wire cages on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h) with ad libitum access to pelleted rodent diet (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN), except as indicated. Water was available at all times. All procedures performed were approved by the Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, according to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Surgeries

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg), xylazine (25 mg/kg), and acepromazine (2 mg/kg) and implanted with stainless steel guide cannulas (26 gauge; Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA) aimed for either the LV, 4V, or the medial NTS. Cannulas were secured to the skull using stainless steel screws and methacrylate. During the first 48 h after surgery, analgesic (flunixamine, 2.5 mg/kg) was injected im every 12 h. Rats were allowed 2 wk recovery, by which time they all exceeded their presurgery body weights.

Food intake after leptin injections into the LV, 4V, or dorsal vagal complex

For measurements of food intake and body weight after LV (n = 11) or 4V (n = 11) leptin injection, recombinant murine leptin (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) dissolved in 0.9% NaCl (3 μg in 3 μl) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) (3 μl) was injected 2 h before lights out (1700 h), on 2 consecutive days. Injections were made using a 10-μl Hamilton syringe connected to 33 gauge injectors (Plastics One Inc.) inserted into the 26-gauge guide cannulas, and extending 0.5 mm beyond the tip of the guide cannula. Body weight and food intake (Harlan Teklad) were measured at 0900 h daily for two consecutive 24-h periods after the two leptin injections. On d 3, food was removed from the cages, and each rat received a third leptin or vehicle injection. Ninety minutes later, the rats were euthanized to collect brain tissue for determination of STAT3 phosphorylation in hindbrain and hypothalamus using Western blot analysis (see below). In a separate group of rats, leptin dissolved in 0.9% NaCl (50 ng in 50 nl) (n = 6) or vehicle (NaCl) (50 nl) (n = 5) was injected unilaterally via cannulas with tips residing in or immediately ventral to the NTS. These rats were injected with leptin or vehicle 2 h before lights out (1700 h), on 2 consecutive days, using a motor-driven nanoinjector pump. Body weights and food intakes (Harlan Teklad) were measured at 0900 h for two 24-h periods after the two leptin injections. No pSTAT3 immunohistochemical or Western blotting data were collected for this group of rats.

Western blot analysis

Collection of brain tissue for Western blot estimation of total STAT3 and pSTAT3 was accomplished as described previously (26). Dissection of the hypothalamus was bounded dorsally by the dorsal edge of the third ventricle, laterally by the optic tracts, caudally by the mammillary bodies and rostrally by the optic chiasm. The caudal hindbrain dissections were bounded rostrally by a coronal line between the lateral recesses, caudally by a coronal section through the pyramidal decussation, and ventrally by a horizontal section through the rostrocaudal plane of the central canal and extended rostrally to the anterior border of the lateral recesses. The dissected tissues were frozen, sonicated in lysis buffer, centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80 C until analysis. For electrophoresis, all samples were diluted to yield 10 μg of protein per sample before loading the polyacrylamide gels [Bio-Rad ReadyGel (Hercules, CA), 10% agarose]. After electrophoretic separation, the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), blocked in 5% nonfat milk, and incubated overnight at 4 C in an antibody specific for STAT3 phosphorylated at the tyrosine 705 phosphorylation site (1:2000, rabbit antiphospho-STAT3(tyr705), no. 1319, lot 6; Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA). After washing, the membranes were incubated in secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (goat antirabbit IgG 1:4000, Dako USA, Carpinteria, CA; lot 00003918) for 1 h and washed again. Then an ECL Plus chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was used to visualize pSTAT3 protein bands on film, using a Kodak M35 X-OMAT processor (Rochester, NY). For determination of total STAT3, the membranes were stripped, washed, and reincubated with rabbit anti-STAT3 (C-20) primary antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc482, lot J0306). STAT3 bands then were visualized as described above for phosphorylated STAT3. Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) was used to calculate integrated density of Western blot band and the ratio of integrated densities for phospho-STAT3 to total STAT3 was calculated. Results are reported as the averages pSTAT3/STAT3 ratio ± sem.

pSTAT3 immunohistochemistry after injections into the dorsal vagal complex

Rats received a single injection of leptin (50 ng in 50 nl) or vehicle (50 nl) 2 h before lights off via a cannula aimed for the caudal NTS. Ninety minutes after injection, the rats were rapidly anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation anesthesia and transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4, 300 ml), followed by ice cold 4% paraformaldehyde fixative (pH 7.4; 250 ml). Brains were collected and postfixed for 1 h in the same fixative, and then placed in a cryoprotectant containing 25% sucrose for 24 h. Thirty-micrometer sections through the hypothalami and hindbrains were prepared using a cryostat microtome. Hindbrain sections were stained with cresyl violet and examined to verify the location of cannula tips in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Hypothalamic sections were processed for immunohistochemical detection of pSTAT3, using a phospho-specific primary antibody raised in rabbit against phospho-STAT3(tyr705) (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA; no. 1319, lot 6, 1:1000) followed by biotinylated donkey antirabbit secondary antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), with subsequent incubation in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). A conventional nickel-enhanced diaminobenzidine/hydrogen peroxide reaction was used to reveal antigen/antibody/avidin complexes.

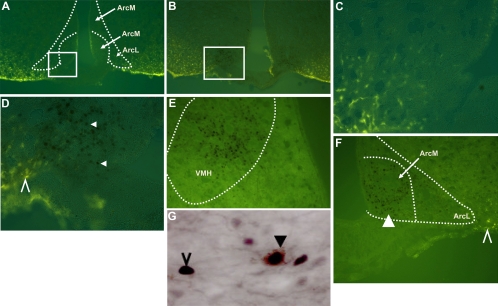

pSTAT3 immunopositive neurons in the hypothalamus of each rat were counted in three sections corresponding to plates 30, 34, and 37 of the Paxinos & Watson rat brain atlas. Areas of interest in which pSTAT3 immunoreactive cells were counted were the medial, lateral, and dorsal ARC nucleus (ARCm, ARCl, and ARCd), medial posterior ARC nucleus (ARCmp), VMH, DMH, and the combined perifornical and lateral hypothalamic areas (PeF/LH). Although pSTAT3-immunopositive cells were counted separately for the right and left sides of the hypothalamus, there was no significant difference in pSTAT3 immunoreactivity between the right and left sides. Therefore, the counts for right and left sides were summed for presentation here.

Determination of plasma leptin concentrations after NTS injection of leptin

To determine whether NTS injections of leptin resulted in altered circulating leptin concentrations, we measured both rat leptin (endogenous leptin) and human leptin (exogenous leptin) immunoreactivity after a single NTS injection of recombinant human leptin (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) (50 ng in 50 nl) (n = 15) or vehicle (50 nl) (n = 15). Rats (n = 5/group/time point) were killed at 15, 30, or 90 min after human leptin or vehicle injection and trunk blood was collected into ice chilled tubes containing EDTA and aprotinin and immediately centrifuged at 4 C. Plasma samples were decanted and stored at −80 C until further processing. Plasma rat and human leptin immunoreactivities were determined using RIAs specific for rat and human leptin, respectively (Linco Research/Millipore, St. Charles, MO). Antisera used for the assay of human leptin had less than 0.2% cross-reactivity for rat leptin. Similarly, antisera used in the assay for rat leptin had less than 2% cross-reactivity for human leptin. All leptin measurements were made in duplicate.

Estimation of diffusion of hindbrain injections to hypothalamic pSTAT3 immunoreactive areas

The possibility that 4V or dorsal vagal complex injections permitted injected material to reach the hypothalamus was assessed by injecting the fluorescent retrograde tracer fluorogold (FG) into the 4V or the NTS 24 h before injections of leptin or vehicle via the same cannulas, then processing the brains to reveal both FG fluorescence and pSTAT3 immunoreactivity. Rats implanted with 4V cannulas received either leptin (3 μg in 3 μl) (n = 5) or vehicle (n = 4) 24 h after receiving an equivalent 4V injection volume (3 μl) of 2% FG. Likewise, rats implanted with NTS cannulas were injected either with leptin (50 ng in 50 nl) (n = 4) or vehicle (50 nl) (n = 3) 24 h after receiving NTS injections of 2% FG (50 nl) via the same cannulas. Although retrograde transport of FG over long distances in the nervous system might be expected to take longer than 24 h, our intent was to examine the distribution of FG that is likely to arrive at local hypothalamic neurons and terminals much more rapidly, via cerebrospinal fluid. Consequently, we waited just 24 h to detect only those cells likely to be directly exposed to the tracer, and by inference leptin, via this CSF route. Ninety minutes after leptin or vehicle injection, the rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, exsanguinated, and perfused in preparation for detection of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity, as described above. Thirty-micrometer hypothalamic sections were examined for distribution of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity and FG.

Statistics

Changes in body weights and daily food intakes after injections into the cerebral ventricles or the dorsal hindbrain were compared using two-way repeated measures ANOVA (repeated factor being the day of measurement). Differences in pSTAT3/STAT3 ratio on Western blots of leptin and vehicle-injected rats also were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA, with the repeated factor being the area of the brain analyzed. For statistical analysis, counts of pSTAT3-immunopositive neuronal nuclei from all three sections from each rat were summed for each area of interest determined from atlas plate level (ARCm, ARCl, ARCd, VMH, DMH, and PeF/LH for sections at plate levels 30 and 34, ARCmp for the section at plate level 37). Counts of pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in rats that received NTS injections of leptin or vehicle were compared with those of rats injected with vehicle by repeated measures ANOVA, with brain area of interest counted being the repeated factor. Holm Sidak comparison was used for all multiple comparisons after ANOVA. Plasma rat and human leptin concentrations after NTS injection of human leptin were analyzed for significance using two-way ANOVAs. SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

Loss of body weight and reduction of food intake after LV or 4V leptin injections

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in body weight and food intake that occurred after LV (Fig. 1, A and B) or 4V (Fig. 1, C and D) injection of leptin or vehicle. There was no difference in body weight between leptin- or vehicle-treated groups before LV injection of leptin or vehicle. Rats in the vehicle group (n = 5) weighed 348 ± 6.4 g before the first injection, and the leptin group (n = 6) averaged 342 ± 8.2 g. Likewise, before ventricular injection, the body weights of rats receiving 4V vehicle injection (327 ± 5.6 g) (n = 5) did not differ from the weights of those that received leptin (322 ± 2.7 g) (n = 6).

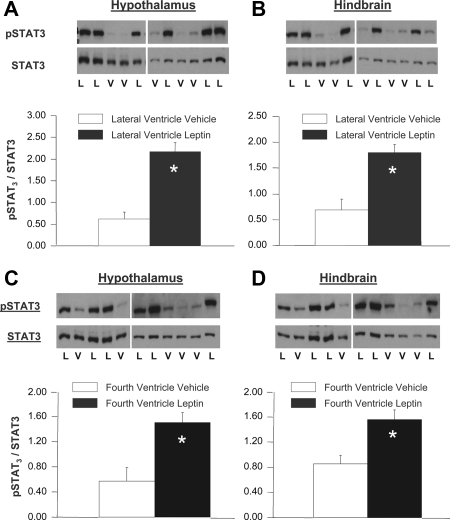

Figure 1.

Cumulative change in body weight (A and C) and 24 h food intake (B and D) on 2 d after daily administration of either leptin (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 5) injected via the LV (A and B) or leptin (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 5) injected via the 4V (C and D). Leptin-injected rats exhibited significantly greater loss of body weight, compared with vehicle-injected rats, on both d 1 and 2 of injection, regardless of whether injections were made via LV or 4V. Similarly, leptin-injected rats exhibited reduced food intake, compared with vehicle-injected rats, on both d 1 and 2 after LV leptin injection, but reduction of intake was significant only for d 1 after 4V leptin injection. The failure of reduced food intake to reach statistical significance on d 2 after 4V leptin probably was due to the fact that 4V vehicle itself produced a slight reduction of food intake. Error bars show sem. *, Significant difference from vehicle-injected controls (P < 0.001).

LV leptin administration resulted in significant loss of body weight compared with vehicle administration [F(3,18) = 46.99, P < 0.001]. Body weight loss after LV leptin was significant on both d 1 (−6.6 ± 3.3 g) and 2 (−15.6 ± 2.3 g) of treatment (P < 0.001). By contrast, vehicle-injected rats actually gained significant body weight after the first and second LV injection (d 1, 6.3 ± 1.1 g; d 2, 10.0 ± 1.3 g, P < 0.001). 4V leptin injection (n = 6) was associated with significant loss of body weight on both d 1 (−14.5 ± 2.2 g) and 2 (−19.2 ± 2.0 g) (P < 0.001). Unlike LV injection, however, 4V injection of vehicle (n = 5) also produced a slight but nonsignificant reduction of body weight (d 1, −1.0 ± 1.4 g; d 2, −2.2 ± 0.9 g).

Rats injected with intraventricular leptin ate significantly less than those that received vehicle injections [F(3,18) = 13.21, P < 0.001]. Rats treated with LV leptin ate 17.9 ± 1.7 g after the first leptin injection (d 1), and 12.4 ± 1.2 g after the second leptin injection (d 2). These consumptions were significantly less (P < 0.001) than intakes of the vehicle-injected rats (d 1, 24.7 ± 1.3 g; d 2, 22.8 ± 0.8 g). Likewise, after 4V, leptin rats ate significantly less than 4V vehicle-injected rats on both days of the experiment (P < 0.001). Specifically, rats that received 4V leptin (n = 6) ate 12.9 ± 1.7 g and 14.8 ± 2.3 g on d 1 and 2, respectively, and 4V vehicle rats (n = 5) ate 23.6 ± 1.1 g and 20.4 ± 1.7 g on d 1 and 2.

Western blot analysis indicates that LV or 4V leptin injections produce comparable increases in basomedial hypothalamic and dorsocaudal medulla STAT3 phosphorylation

After LV or 4V leptin injection, pSTAT3 immunoreactivity was significantly increased in both the basomedial hypothalamus (Fig. 2, A and C) and the dorsocaudal hindbrain (Fig. 2, B and D) compared with vehicle-injected rats [F(3,18) = 19.64, P < 0.001]. LV leptin (n = 6) significantly increased pSTAT3 in both hypothalamus (P < 0.001) and the hindbrain (P < 0.001) compared with LV vehicle injection (n = 5). The 4V leptin (n = 6) significantly (P = 0.001) increased the pSTAT3 in the hindbrain compared with 4V vehicle (n = 5). 4V leptin also significantly increased pSTAT3 in the hypothalamus (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Change in STAT3 phosphorylation (pSTAT3) in the hypothalamus and dorsal hindbrain, after daily LV (A and B) or 4V (C and D) injections of leptin (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 5) over 3 d. Results represent averages from six LV and six 4V leptin-injected rats, five LV and five 4V-vehicle-injected rats. Rats were euthanized 90 min after the final ventricular injection on d 3, at which time brain tissue was collected for Western blot analysis. The top portions of the panels show actual Western blots of pSTAT3 and total STAT3 immunoreactivity for individual animals that received either leptin (L) or vehicle (V). Changes in pSTAT3 immunoreactivity, graphed in the lower portions of the panels, are the average of the ratios of integrated pSTAT3 band density to integrated total STAT3 band density for each treatment group. The Western blot analyses compared the effects of leptin or vehicle treatment within each brain area, but are not suitable for comparisons between brain areas. Error bars show sem. Both LV and 4V leptin injections significantly increased pSTAT3 in both hypothalamus and hindbrain, compared with vehicle injected controls. *, Significant difference from vehicle-injected controls (P < 0.001).

Food intake and body weight after leptin injections into the dorsal hindbrain

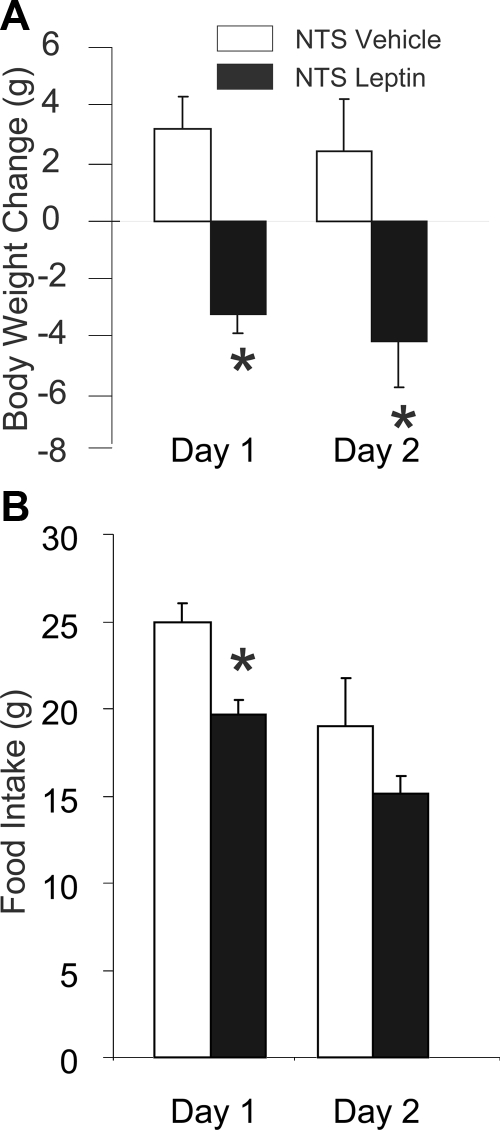

Injection of leptin (50 ng in 50 nl) into the NTS (n = 6) on 2 consecutive days resulted in significant loss of body weight compared with rats that received 50 nl vehicle injections (n = 7) (Fig. 3A). Initial body weights on the day before the first leptin or vehicle injection were 339 ± 4.1 g for leptin-treated rats and 343 ± 5.5 g for saline-treated rats, and the weights of these groups did not differ significantly. Leptin-injected rats lost more weight during the experiment than vehicle-injected rats [F(1,11) = 14.83, P = 0.003]. The weight loss after leptin was significantly greater than in vehicle-injected rats, which maintained positive increases in weight over the 2 d (P = 0.008) and d 2 (P = 0.006). Rats injected with leptin into the NTS ate significantly less than rats injected with vehicle [F(1,11) = 10.58, P = 0.008] (Fig. 3B). This effect of leptin was due to significant reduction on d 1 (P = 0.048), but not d 2 (P = 0.14).

Figure 3.

Cumulative change in body weight (A) and daily 24 h food intake (B) for 2 d, after daily administration of either leptin (n = 6) (50 ng in 50 nl) or vehicle (n = 7) (50 nl), injected directly into the nucleus of the solitary tract of the dorsal medulla. Leptin-injected rats lost significantly more body weight than vehicle-injected rats on both d 1 and d 2 of the experiment. Similarly, rats the received leptin ate significantly less than vehicle-injected rats, but the reduction of was statistically significant only for d 1. Error bars show sem. *, Significant difference in reduction of body weight compared with vehicle-injected controls (P < 0.01), and significant difference in reduction of food intake compared with vehicle-injected controls (P < 0.05).

Hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation after a single low-dose leptin injection into the dorsal hindbrain

Histological examination of hindbrain sections to localize cannula tip placements in the dorsal medulla revealed that tips of all but one dorsal hindbrain cannula resided in the dorsal vagal complex between the solitary tract and the lateral edge of the area postrema. All except one cannula tip were located dorsal to the ventral edge of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. The tip of this rat’s cannula was located at the ventral border of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, and was not eliminated from the analysis.

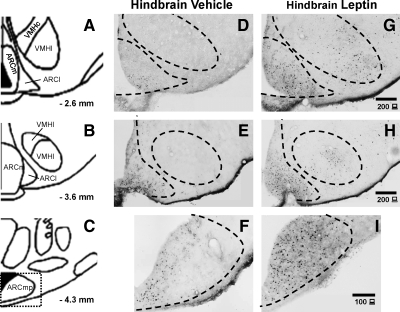

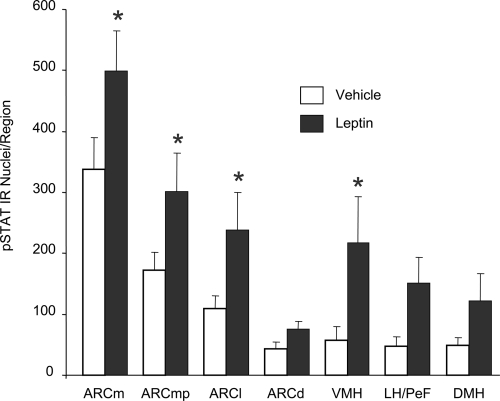

Images in Fig. 4 are from representative hypothalamic sections in which numbers of pSTAT3 immunoreactive cells were counted after NTS injection of vehicle (n = 7) (50 μl) (Fig. 4, D–F) or leptin (n = 6) (50 ng in 50 nl) (Fig. 4, G–I). The quantifications of immunohistochemical data at these levels in each rat are depicted in Fig. 5. NTS leptin injection significantly increased pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in the hypothalamus [F(1,11) = 10.85, P = 0.007]. Compared with vehicle-injected controls, leptin injection into the NTS significantly increased numbers of pSTAT3 immunoreactive cells in several hypothalamic areas of interest (P < 0.05). Specifically, NTS leptin injection increased pSTAT3 immunoreactive cell numbers in the ARCm (P = 0.008), ARCmp (P = 0.03), ARCl (P = 0.03), and VMH (P = 0.009). There also were trends toward leptin-induced increases of pSTAT3 immunoreactive cells in the DMH and LH/PeF, but these trends did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated STAT3 immunoreactivity in the basomedial hypothalami of rats 90 min after a single 50-nl injection of vehicle (D–F) or leptin (50 ng in 50 nl) (G–I) directly into the nucleus of the solitary tract. A, B, and C illustrate boundaries examined and counted, as illustrated in representative sections D, E, G, and H. To reduce clutter, the boarder between the ArcM and ArcL is not depicted on the immunohistochemical images (D,G, E, and H). The area bounded by the dashed rectangle in C defines the area of the hypothalamus depicted in F and I. ArcL, ARCl nucleus; ArcM, ARCm nucleus; ArcMP, medial posterior ARC nucleus; VMHC, central VMH nucleus; VMHL, lateral VMH nucleus.

Figure 5.

Average number of pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in the hypothalamus of rats 90 min after a single 50-nl injection of vehicle or leptin directly into the nucleus of the solitary tract. Error bars show sem. Leptin was associated with significantly increased numbers of pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in the VMH and in all areas of the ARC nucleus (ArcL, ArcM, ArcMP), except the ARCd. There were trends toward increased pSTAT3 in the lateral and perifornical hypothalamus (LH/PeF) and DMH, but these trends did not achieve statistical significance. *, Significantly different from vehicle, P < 0.03.

Concentrations of endogenous and exogenous leptin in the blood plasma after hindbrain leptin injection

Neither human (exogenous) nor rat (endogenous) leptin concentrations were elevated after NTS injection of 50ng/50nl human leptin in overnight fasted rats [(1) = 0.35, P = 0.56]. Moreover, plasma levels of neither human nor rat leptin varied across sampling times [F(2) = 1.36, P = 0.28]. Rat leptin immunoreactivity averaged from 0.74 and 1.21 ng/ml for vehicle-injected rats and 0.69 to 0.90 ng/ml in leptin-injected rats, and human leptin immunoreactivity was not detectable at any time in either group.

Distribution of FG and pSTAT3 after hindbrain injections

A 4V FG injection 24 h before leptin or vehicle injection revealed that FG injected via this route reached the subarachnoid space adjacent to the basomedial hypothalamus in rats injected via this route. However, FG fluorescence was restricted to what appeared to be glial processes adjacent to the pial surface. Although there were few pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in hypothalamic sections from rats injected with vehicle, all rats injected with 4V leptin exhibited abundant pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei in the ARC and VMH. However, the distribution of FG fluorescence did not overlap with the areas of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity (Fig. 6, A–D), and no cells that exhibited pSTAT3 immunoreactivity and FG fluorescence were observed. As in our previous NTS leptin injections exhibited increased pSTAT3 immunoreactivity compared with vehicle-injected controls. In three of the four rats that received NTS injection of FG 24 h before leptin, no FG fluorescence was observed outside of the hindbrain injection site. However, in sections from one rat, a trace of what appeared to be FG fluorescence was detected on the pial surface of the hypothalamus. Nevertheless, there was no overlap between the area of FG labeling and areas that exhibited pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei (Fig. 6, E and F).

Figure 6.

A–F, Digital images of 30-μm coronal hypothalamic sections illustrating the distribution of fluorogold (yellow) and pSTAT3 immunoreactivity (black nuclear staining). Fluorogold was injected into the hindbrain 24 h before injection of either leptin or vehicle, and brains were collected for immunohistochemistry 90 min after injection of leptin or vehicle. Although fluorogold could be retrogradely transported to neuronal cell bodies with projections to the NTS, the 24 h allowed between FG injection and brain harvesting precludes this route for FG arrival in the hypothalamus. Hence, FG labeling is taken to indicate arrival of the tracer via diffusion in cerebrospinal fluid. A and C, Low- and high-power images from the same section from a vehicle-injected rat. The solid square in panel A encloses the area covered in panel C. Dotted lines indicate the border of the ARC nucleus, including the ArcD, ArcM, and ArcL subnuclei. Note the distribution of fluorogold and the virtual absence of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity in the ARC of this rat that received a vehicle injection (300 μl), but no leptin, 24 h after a 300-μl injection of 2% FG via the same 4V cannula. B and D, Images of comparable fields illustrating the distribution of fluorogold and pSTAT3 immunoreactivity in the ARC when fluorogold was injected into the hindbrain 24 h before injection of leptin via the same 4V cannula. The square in panel B indicates the area covered at higher power in panel D. Note the abundance of pSTAT3 immunoreactive nuclei (solid arrowheads) as well as FG labeling, which exhibits little or no overlap with pSTAT3 immunoreactivity. E and F, Images from the hypothalamus of an animal that received leptin (50 ng in 50 nl) injected into the NTS 24 h after a 50-nl injection of 2% fluorogold injected via the same cannula. Note the very limited fluorgold labeling of hypothalamus adjacent to pial surface and the presence of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity in the VMH (E) and ARC (F). In no case were pSTAT3 immunoreactive cells found to be labeled by fluorogold. Fluorogold distribution was largely nonoverlapping with areas of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity, after 4V injections, and fluorogold labeling of the pial surface could be found in just one of four rats that received 50 ng in 50 nl of fluorogold. G, Dual-label immunohistochemical preparation from a rat injected with 50 ng of leptin in 50 nl, directly in to the dorsal vagal complex. pSTAT3 immunoreactivity was clearly present in both α-MSH immunoreactive neuron (brown, closed arrowhead) and α-MSH-negative neurons (open arrowhead). However, all detectable MSH immunoreactive neurons also were immunoreactive for pSTAT3. α-MSH neurons are directly sensitive to leptin. Thus, colocalization of pSTAT3 immunoreactivity with α-MSH immunoreactivity in the arcuate area is compatible with direct activation of these neurons by hindbrain-injected leptin.

Discussion

Leptin receptor mRNA and immunoreactivity (8,27) are expressed by neurons in the hindbrain dorsal vagal complex, an area of the hindbrain that integrates visceral afferent signals controlling food intake. Furthermore, the findings of Grill and co-workers (10), confirmed by our own, indicate that hindbrain leptin injections can produce comparable reductions of food intake and body weight to those observed after injection of leptin into the forebrain. Taken together, these observations suggest that leptin can act directly on the hindbrain to reduce food intake and body weight. Nevertheless, there has been no direct evidence to conclusively rule out hypothalamic participation in the response to hindbrain leptin. Furthermore, there are no published tests of the hypothesis that hindbrain injections may be able to trigger leptin-mediated signaling in the forebrain. In experiments described here, we found that leptin injection into the 4V or directly into the dorsal vagal complex triggered rapid and significant increase of hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation. These results suggest that the hypothalamus may participate in behavioral and metabolic responses to hindbrain leptin applications.

Leptin binding to the long or signaling splice variant of its receptor, LRb, results in activation of JAK2 with subsequent phosphorylation of STAT3 (16). Leptin action also is associated with additional intracellular signaling cascades (reviewed in Ref. 28). However, increases in expression of signaling molecules such as Fos, phosphorylated ERK1/2, or CREB are not directly or uniquely coupled to leptin receptor binding, and may also occur in indirectly activated neurons (29,30) downstream to those that are directly activated by leptin. Although leptin is not the only agent with actions coupled to increased phosphorylation of STAT3 (see, for example, Refs. 31,32,33,34), increased STAT3 phosphorylation is widely viewed as evidence of direct cellular activation via binding of leptin to its receptor, especially in experiments in which exogenous leptin is administered (25,26,27,28).

At this time, we can only speculate with regard to the mechanism or route by which leptin applied to the hindbrain triggers STAT3 phosphorylation in the hypothalamus. However, there are at least two potential explanations. The first and simplest explanation is that, after hindbrain injection, leptin somehow reaches the hypothalamus in concentrations sufficient to trigger STAT3 phosphorylation. A second possibility is that leptin activates hindbrain neurons, projecting to the hypothalamus, and that terminals of these neurons release a neurotransmitter that is capable of triggering STAT3 phosphorylation in hypothalamic neurons.

There are several putative avenues by which hindbrain injected leptin conceivably could reach the hypothalamus. One potential route by which leptin injected into the 4V or dorsal vagal complex might reach the hypothalamus is by increasing plasma leptin concentrations, thereby mimicking the endocrine avenue of hypothalamic activation. In support of this possibility, van Dijk and colleagues (35) have reported that exogenous leptin (3.5 μg) injection into the 3rd cerebral ventricle triggers an increase in circulating concentrations of endogenous leptin. We examined this possibility directly by measuring the plasma concentrations of leptin after hindbrain injection of exogenous human leptin. Our observation that circulating levels of exogenous human or endogenous rat leptin were not elevated by hindbrain leptin injection excludes the blood circulation as the mechanism by which our injections could have affected hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation.

It is conceivable that hindbrain-injected leptin might reach the hypothalamus by reflux through the cerebral aqueduct to the third ventricle. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid through the brain’s ventricular system is from the rostral forebrain ventricles to the third ventricle and through the cerebral aqueduct to the 4V. Moreover, functional and anatomical studies suggest that small volumes injected into the rat 4V do not reflux into the third ventricle. For example, the peptide angiotensin II evokes increased water drinking when it acts at structures adjacent to the third ventricle, the subfornical organ (36,37) and in the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT) (38,39,40). Although injections of small amounts of this peptide in or near the forebrain ventricles trigger vigorous drinking, injection of angiotensin II into the 4V is without effect (41,42), suggesting that this potent hormone does not reach its periventricular forebrain sites of action by reflux from the 4V. During our own previous work, in which we examined responses to forebrain and hindbrain antimetabolite injections (41), we concluded that, although LV injections of dye or antimetabolite rapidly distribute to the 4V, small volumes injected into the 4V do not reflux through the aqueduct to the third and LV. Similarly, Proescholdt et al. (43) observed that although a 5-μl bolus injection of 14C inulin via the cisterna magna strongly labeled the 4V, there was no labeling of the cerebral aqueduct or evidence for reflux of the tracer to the forebrain ventricles. Finally, in the current experiments we found no indication that FG injected into the 4V reached the forebrain ventricles. Similarly, we observed no FG labeling in the cerebral aqueduct, or third ventricle of any rats after NTS FG injection. Thus, it seems unlikely that hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation after 4V or NTS leptin injection is due to ventricular reflux to the third ventricle.

Another avenue by which hindbrain-injected leptin might reach some hypothalamic sites is via the subarachnoid space. Ghersi-Egea et al. (44) reported that after rapid LV infusion of 500 nl 14C sucrose, the tracer appears in the subarachnoid space, with small but detectable amounts of 14C detected as far rostral as the optic chiasm. These investigators could not determine whether 14C sucrose penetrated into the hypothalamus through the pial membrane. However, Proeshodt et al. (43) found that, after a 5-μl cisterna magnum injection, 14C-labeled inulin did penetrate the ventral surface of the hypothalamus to a depth of as much as 0.3 mm. These reports suggest that substances injected into the brain ventricles may in some cases reach remote sites of action via a subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid. Of additional importance with regard to leptin action is a report that suggests intrathecally administered leptin could reach a hypothalamic site of action via the subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid. McCarthy et al. (45) used positron emission tomography to observe the movement of leptin conjugated to diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid administered into the lumbar space of baboons. They found that in two of three baboons conjugated leptin reached the surface of the hypothalamus in 90 or 139 min after injection. Yaksh et al. (46) reported that intrathecal leptin infusions of 10 μg/d to rats reduced food intake and body weight significantly more than infusions of isotonic saline. Although these investigators measured a dramatic increase in immunoreactive leptin in the cisterna magna after their intrathecal injections, they did not chart the distribution of their infusate beyond this point. Nevertheless, taken together with the McCarthy et al. (45) results, it is not unreasonable to speculate that all or part of the functional effects observed were associated with leptin reaching the hypothalamus. Neither the results of McCarthy et al. (45), nor those of the Yaksh et al. (46) justify concluding that our much smaller volumes delivered into the dorsal vagal complex reached the hypothalamus via the subarachnoid space. In fact, although we found the fluorescent tracer, fluorogold, was detectable along the pial surface of the hypothalamus 24 h after 4V injection, the distribution of FG did not overlap pSTAT3 immunoreactive neurons observed after leptin injection via the same cannulas in the same rats. Likewise, we saw no indication that FG injected in much smaller volume reached pSTAT3 immunoreactive areas of the hypothalamus. It should be emphasized that FG is concentrated in neuron soma by retrograde transport. FG injections in our studies were administered just 24 h before collection of tissue for pSTAT3 immunohistochemistry. This length of time is too short for retrograde transport from the hindbrain, but would be sufficient for transport of FG by short hypothalamic neuronal processes close to the pial surface and bv glial processes. Hence, it is noteworthy that we found no retogradely labeled neurons in known hindbrain projection areas of the forebrain. Therefore, the FG labeling that was observed did not represent retrograde transport of the dye from the hindbrain. Rather, hypothalamic FG labeling after our injections indicates movement of the dye to cells near the hypothalamic pial surface via the subarachnoid space. Although the nonoverlap of visible FG labeling and pSTAT3 immunoreactivity would seem to be evidence against the spread of hindbrain-injected leptin to the hypothalamus via the cerebrospinal fluid, leptin is a hormone capable of triggering neuronal responses at picomolar concentrations. Moreover, neurons of the basomedial hypothalamus might well express LRb on dendrites that extend to the pial surface where exposure to leptin from the subarachnoid space could occur. In this regard, it is worth noting that FG may not have reached sufficient concentrations to label hypothalamic neurons via juxta-pial dendrites. Therefore, it remains entirely possible that hindbrain injected leptin might reach leptin receptive neurons in the hypothalamus, although FG concentrations at these sites may be beneath detection limits. Consistent with this possibility is the fact that the increase in pSTAT3 immunoreactivity that we observed after hindbrain leptin injections only was observed in areas where leptin receptive neurons are abundant. Nevertheless, we cannot safely conclude that subarachnoid movement of leptin from the hindbrain to the hypothalamus is the sole mechanism by which hindbrain-injected leptin triggers hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation.

An alternative, but in our view less probable, mechanism by which hindbrain leptin might trigger increased pSTAT3 immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus will require additional investigation. Specifically, it is conceivable that leptin activates hindbrain neurons that project to the hypothalamus. The terminals of these neurons could release a neurotransmitter/neuromodulator that triggers hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation. Although this explanation seems novel, it is not without experimental support. For example, de Jonge et al. (47) demonstrated that vagal stimulation triggers STAT3 phosphorylation in intestinal macrophages. Furthermore, these investigators found that vagally mediated STAT3 phosphorylation depended upon recruitment of JAK2 by the α7 subunit of the nicotinic receptor. Similarly, Ikeda et al. (48) reported that vagal acetylcholine increases STAT3 phosphorylation during hepatic regeneration, and that this effect also is mediated by the nicotinic receptor α7 subunit. Although there have been no systematic investigations of neurotransmitter-mediated changes in STAT3 phosphorylation in neurons, several reports indicate that 5-HT receptor antagonists increase pSTAT3 in cerebral cortex in vivo (49,50). Furthermore, norepinephrine is reported to trigger STAT3 phoshorylation in PC12 cells (51). Although the reports referenced above raise the possibility that some hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation could be synaptically driven it would seem that if this mechanism had been operative in our experimental setting, we might have observed a distribution of forebrain STAT3 phosphorylation that did not overlap with areas of leptin receptor expression. However, the distribution of hypothalamic pSTAT3 that we detected after hindbrain leptin injection conformed with patterns of STAT3 phosphorylation observed after systemic leptin injection. Therefore, although a synaptic mechanism for STAT3 phosphorylation cannot be ruled out, it seems less plausible than a diffusional mechanism.

In summary, our observations confirm prior reports (10) that hindbrain and forebrain leptin injections induce comparable reductions of food intake and body weight. However, we observed that even nanogram doses of leptin reliably trigger phosphorylation of STAT3 in the hypothalamus. These results suggest either that hindbrain leptin activates neurons in the hypothalamus via neuronal projections, or that leptin reaches leptin-sensitive hypothalamic neurons via the CSF in the subarachnoid space. Although one may not conclude from our current results that hypothalamic STAT3 phosphorylation is required for reduction of food intake and body weight after hindbrain leptin injection, our demonstration of a prototypical leptin signal in hypothalamic neurons far removed from the site of leptin injection raises the possibility that remotely activated neurons contribute to integrated behavioral and metabolic responses to local leptin applications.

Footnotes

Current address for M.R.: Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism C4-R, Leiden University Medical Center, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-20561 (to R.C.R.), DK-67146 (to S.M.S.) and Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research Rubicon grant (to M.R.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 25, 2010

Abbreviations: ARC, Arcuate; ARCd, dorsal ARC; ARCl, lateral ARC; ARCm, medial ARC; DMH, dorsomedial hypothalamus; FG, fluorogold; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; l, lateral; LRb, leptin receptor; LV, right lateral cerebral ventricle; m, medial; mp, medial posterior; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; PeF/LH, perifornical and lateral hypothalamic area; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; 4V, fourth ventricle; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamus.

References

- Green ED, Maffei M, Braden VV, Proenca R, DeSilva U, Zhang Y, Chua Jr SC, Leibel RL, Weissenbach J, Friedman JM 1995 The human obese (OB) gene: RNA expression pattern and mapping on the physical, cytogenetic, and genetic maps of chromosome 7. Genome Res 5:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM 1994 Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372:425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederich RC, Löllmann B, Hamann A, Napolitano-Rosen A, Kahn BB, Lowell BB, Flier JS 1995 Expression of ob mRNA and its encoded protein in rodents. Impact of nutrition and obesity. J Clin Invest 96:1658–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P 1995 Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269:546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM 1995 Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 269:543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F 1995 Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 269:540–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Caro JF 1997 Leptin and the regulation of body weight. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 29:1255–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyse M, Ovesjö ML, Goïot H, Guilmeau S, Péranzi G, Moizo L, Walker F, Lewin MJ, Meister B, Bado A 2001 Expression and regulation of leptin receptor proteins in afferent and efferent neurons of the vagus nerve. Eur J Neurosci 14:64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Bjorbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB 1998 Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 395:535–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Schwartz MW, Kaplan JM, Foxhall JS, Breininger J, Baskin DG 2002 Evidence that the caudal brainstem is a target for the inhibitory effect of leptin on food intake. Endocrinology 143:239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel JD, Trinko R, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Liu ZW, Gao XB, Thurmon JJ, Marinelli M, DiLeone RJ 2006 Leptin receptor signaling in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates feeding. Neuron 51:801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi T, Kawagishi T, Okuma Y, Tanaka J, Nomura Y 2002 Brain stem is a direct target for leptin’s action in the central nervous system. Endocrinology 143:3498–3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellacott KL, Halatchev IG, Cone RD 2006 Characterization of leptin-responsive neurons in the caudal brainstem. Endocrinology 147:3190–3195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Banks WA 2004 Obesity-prone rats have normal blood-brain barrier transport but defective central leptin signaling before obesity onset. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R143–R150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghilardi N, Skoda RC 1997 The leptin receptor activates janus kinase 2 and signals for proliferation in a factor-dependent cell line. Mol Endocrinol 11:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisse C, Halaas JL, Horvath CM, Darnell Jr JE, Stoffel M, Friedman JM 1996 Leptin activation of Stat3 in the hypothalamus of wild-type and ob/ob mice but not db/db mice. Nat Genet 14:95–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, Schubert M, Tso AW, Wang Y, Banks AS, Lavery HJ, Haq AK, Maratos-Flier E, Neel BG, Schwartz MW, Myers Jr MG 2003 STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 421:856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin DG, Hahn TM, Schwartz MW 1999 Leptin sensitive neurons in the hypothalamus. Horm Metab Res 31:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CC, Clifton DK, Steiner RA 1997 Proopiomelanocortin neurons are direct targets for leptin in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology 138:4489–4492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Kelly JF, Lee CE, Ahima RS, Drucker DJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK 2000 Chemical characterization of leptin-activated neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 423:261–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Campfield LA, Burn P, Baskin DG 1996 Identification of targets of leptin action in rat hypothalamus. J Clin Invest 98:1101–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Yao F, Hockman K, Heng HH, Morton GJ, Takeda K, Akira S, Low MJ, Rubinstein M, MacKenzie RG 2008 Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 is required in hypothalamic agouti-related protein/neuropeptide Y neurons for normal energy homeostasis. Endocrinology 149:3346–3354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzberg H, Huo L, Nillni EA, Hollenberg AN, Bjørbaek C 2003 Role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in regulation of hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin gene expression by leptin. Endocrinology 144:2121–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Charlat O, Tartaglia LA, Woolf EA, Weng X, Ellis SJ, Lakey ND, Culpepper J, Moore KJ, Breitbart RE, Duyk GM, Tepper RI, Morgenstern JP 1996 Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell 84:491–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards GJ, Campfield LA, Clark FT, Deeds J, Muir C, Sanker S, Moriarty A, Moore KJ, Smutko JS, Mays GG, Wool EA, Monroe CA, Tepper RI 1995 Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell 83:1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JH, Simasko SM, Ritter RC 2007 Leptin analog antagonizes leptin effects on food intake and body weight but mimics leptin-induced vagal afferent activation. Endocrinology 148:2878–2885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer JG, Moar KM, Hoggard N 1998 Localization of leptin receptor (Ob-R) messenger ribonucleic acid in the rodent hindbrain. Endocrinology 139:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Jr MG 2004 Leptin receptor signaling and the regulation of mammalian physiology. Recent Prog Horm Res 59:287–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SS, York RD, Stork PJ 1999 Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signalling in neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol 9:544–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács KJ 2008 Measurement of immediate-early gene activation—c-fos and beyond. J Neuroendocrinol 20:665–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishingrad MA, Koshlukova S, Halvorsen SW 1997 Ciliary neurotrophic factor stimulates the phosphorylation of two forms of STAT3 in chick ciliary ganglion neurons. J Biol Chem 272:19752–19757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand A, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Bertrand C, Escrieut C, Mathieu A, Portolan G, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Dufresne M, Seva C 2005 A novel mechanism for JAK2 activation by a G protein-coupled receptor, the CCK2R: implication of this signaling pathway in pancreatic tumor models. J Biol Chem 280:10710–10715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA 2006 Receptor-mediated tobacco toxicity: cooperation of the Ras/Raf-1/MEK1/ERK and JAK-2/STAT-3 pathways downstream of α7 nicotinic receptor in oral keratinocytes. FASEB J 20:2093–2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepkowski SM, Chen W, Ross JA, Nagy ZS, Kirken RA 2008 STAT3: an important regulator of multiple cytokine functions. Transplantation 85:1372–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk G, Donahey JC, Thiele TE, Scheurink AJ, Steffens AB, Wilkinson CW, Tenenbaum R, Campfield LA, Burn P, Seeley RJ, Woods SC 1997 Central leptin stimulates corticosterone secretion at the onset of the dark phase. Diabetes 46:1911–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiapane ML, Simpson JB 1980 Subfornical organ: forebrain site of pressor and dipsogenic action of angiotensin II. Am J Physiol 239:R382–R389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JB, Epstein AN, Camardo Jr JS 1978 Localization of receptors for the dipsogenic action of angiotensin II in the subfornical organ of rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 92:581–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind RW 1988 Angiotensin and the lamina terminalis: illustrations of a complex unity. Clin Exp Hypertens A 10(Suppl 1):79–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher TN, Keil LC 1987 Regulation of drinking and vasopressin secretion: role of organum vasculosum laminae terminalis. Am J Physiol 253:R108–R120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK, Cunningham JT, Thunhorst RL 1996 Integrative role of the lamina terminalis in the regulation of cardiovascular and body fluid homeostasis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 23:183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter RC, Slusser PG, Stone S 1981 Glucoreceptors controlling feeding and blood glucose: location in the hindbrain. Science 213:451–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WE, Phillips MI 1976 Regional study of cerebral ventricle sensitive sites to angiotensin II. Brain Res 110:313–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proescholdt MG, Hutto B, Brady LS, Herkenham M 2000 Studies of cerebrospinal fluid flow and penetration into brain following lateral ventricle and cisterna magna injections of the tracer [14C]inulin in rat. Neuroscience 95:577–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghersi-Egea JF, Finnegan W, Chen JL, Fenstrermacher JD 1996 Rapid distribution of intracentricularly administered sucrose into cerebrospinal fluid cisterns via subarachnoid velae in rat. Neuroscience 75:1271–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy TJ, Banks WA, Farrell CL, Adamu S, Derdeyn CP, Snyder AZ, Laforest R, Litzinger DC, Martin D, LeBel CP, Welch MJ 2002 Positron emission tomography shows that intrathecal leptin reaches the hypothalamus in baboons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301:878–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Scott B, LeBel CL 2002 Effects of continuous lumbar intrathecal infusion of leptin in rats on weight regulation. Neuroscience 110:703–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge WJ, van der Zanden EP, The FO, Bijlsma MF, van Westerloo DJ, Bennink RJ, Berthoud HR, Uematsu S, Akira S, van den Wijngaard RM, Boeckxstaens GE 2005 Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 6:844–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda O, Ozaki M, Murata S, Matsuo R, Nakano Y, Watanabe M, Hisakura K, Myronovych A, Kawasaki T, Kohno K, Ohkohchi N 2009 Autonomic regulation of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. J Surg Res 152:218–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muma NA, Singh RK, Vercillo MS, D'Souza DN, Zemaitaitis B, Garcia F, Damjanoska KJ, Zhang Y, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD 2007 Chronic olanzapine activates the Stat3 signal transduction pathway and alters expression of components of the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system in rat frontal cortex. Neuropharmacology 53:552–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Shi J, Zemaitaitis BW, Muma NA 2007 Olanzapine increases RGS7 protein expression via stimulation of the Janus tyrosine kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling cascade. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Murphy TJ, Minneman KP 2000 Activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription by α(1A)-adrenergic receptor stimulation in PC12 cells. Mol Pharmacol 57:961–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]