Abstract

Background and purpose:

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) silence genes by deacetylating lysine residues in histones and other proteins. HDAC inhibitors represent a new class of compounds with anti-inflammatory activity. This study investigated whether treatment with a broad spectrum HDAC inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), would prevent cardiac fibrosis, part of the cardiovascular remodelling in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt rats.

Experimental approach:

Control and DOCA-salt rats were treated with SAHA (25 mg·kg−1·day−1 s.c.) for 32 days. Changes in cardiovascular structure and function were assessed by blood pressure in vivo and in Langendorff perfused hearts, ventricular papillary muscle and in aortic rings in vitro. Left ventricular collagen deposition was assessed by histology.

Key results:

Administration of SAHA to DOCA-salt rats attenuated the following parameters: the increased concentration of over 20 pro-inflammatory cytokines in plasma, increased inflammatory cell infiltration and interstitial collagen deposition, increased passive diastolic stiffness in perfused hearts, prolongation of action potential duration at 20% and 90% of repolarization in papillary muscle, development of left ventricular hypertrophy, systolic hypertension and changes in vascular dysfunction.

Conclusions and implications:

The HDAC inhibitor, SAHA, attenuated the cardiovascular remodelling associated with DOCA-salt hypertensive rats and improved cardiovascular structure and function, especially fibrosis, in the heart and blood vessels, possibly by suppressing inflammation. Control of cardiac histone or non-histone protein acetylation is a potential therapeutic approach to preventing cardiac remodelling, especially cardiac fibrosis.

Keywords: histone acetyltransferase, histone deacetylase inhibitor, cardiac remodelling, hypertrophy, fibrosis, hypertension

Introduction

Chronic pathophysiological stress often leads to excessive collagen deposition (fibrosis) in the left ventricle of the heart, as part of the process of cardiovascular remodelling. Cardiac fibrosis is thought to be initiated by the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines leading to fibroblast activation and infiltrating inflammatory cells (Hinglais et al., 1994; Ratcliffe et al., 2000; Kanzaki et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2005a). The common sequence of events that occurs in response to an inflammatory insult can be summarized as haemostasis; recruitment of circulating immune-inflammatory cells; macrophage activation; activation of fibroblasts and formation of a provisional matrix; and remodelling of the granulomatous scar (Brown et al., 2005b). This remodelling of the heart and blood vessels ultimately leads to a decrease in ventricular compliance together with ventricular hypertrophy, conduction abnormalities, increased blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction (Weber et al., 1993; Weber, 1996).

Expression of inflammatory genes, DNA repair and proliferation may be controlled by the degree of acetylation of histone and non-histone proteins produced by histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Adcock, 2007; Halili et al., 2009). HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) represent a new class of anti-cancer drugs with pleiotropic anti-inflammatory responses. HDACi prevent pro-inflammatory cytokine production with therapeutic effects reported in animal models of inflammatory diseases (Tong et al., 2004; Blanchard and Chipoy, 2005; Adcock, 2007; Lin et al., 2007; Halili et al., 2009). Pro-inflammatory cytokines assist in the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the myocardium (Nicoletti and Michel, 1999; Rutschow et al., 2006; Westermann et al., 2006). This initiates an inflammatory cascade liberating arachidonic acid and metabolites formed via 12-lipoxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase derivatives, as well as cysteinyl leukotrienes and thromboxanes with well-defined profibrotic properties (Cruz-gervis et al., 2002; Wen et al., 2003; Levick et al., 2006). The precise HDAC isoforms responsible for cardiovascular remodelling in vivo are not known, with evidence that class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3, 8 and 11), II (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10) and III (sirtuins) generally have pro-hypertrophic, anti-hypertrophic and anti-apoptotic functions in cardiomyocytes respectively (Zhang et al., 2002; Verdin et al., 2003; McKinsey and Kass, 2007). Some HDACi have been shown to blunt cardiac hypertrophy (Antos et al., 2003; Kee et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2006; Gallo et al., 2008), but those studies did not consider the possibility that the anti-inflammatory effects of HDACi could control fibrosis and improve cardiac function. The development of HDACi with selectivity for individual isoforms is still in its infancy. It is also worth noting that there are relatively few truly HDAC-selective compounds and many of those that have been reported to show some selectivity in vitro against different HDAC enzymes have been found by us (Fairlie, Sweet et al. unpublished work) to be fairly toxic to normal human cells (cardiomyocytes, macrophages).

The present study has investigated whether the Food and Drug Administration-approved HDACi, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), prevents cardiovascular remodelling and improves cardiac function in DOCA-salt rats. SAHA is a broad-spectrum (class I and II) inhibitor of HDAC with moderate potency (IC50– 100 nM) that is being used to treat T-cell lymphoma (Richon, 2006). Unlike most HDACi, SAHA is also relatively non-toxic to normal cells and was therefore an appropriate choice for our in vivo study reported here. The present study establishes that SAHA decreases DOCA-induced cardiovascular remodelling in rats, as demonstrated by reductions in the increased systolic blood pressure, collagen deposition, cardiac stiffness, left ventricular hypertrophy, action potential duration (APD) and vascular dysfunction that are characteristic of the DOCA-salt rat as well as decreasing expression of inflammatory cytokines. These findings suggest that inhibition of class I and II HDACs may present a novel approach to preventing the development of these key indicators of cardiovascular remodelling.

Methods

DOCA-salt hypertensive rats

All animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Queensland under the guidelines of the National Medical and Health Research Council, Australia. Male Wistar rats (8–10 weeks old) were obtained from the Central Animal Breeding House of The University of Queensland. Rats were given ad libitum access to food and water and were housed in 12-h light/dark conditions. All treated rats were uni-nephrectomized (UNX). The rats were anesthetised with an intraperitoneal injection of Zoletil (tiletamine (25 mg·kg−1) and zolazepam (25 mg·kg−1)) together with xylazine (10 mg·kg−1, Rompun); a lateral abdominal incision provided access to the kidney, and the left renal vessels and ureter were ligated. The left kidney was removed and weighed, and the incision site was sutured. After uninephrectomy, rats were divided into two groups, UNX, with no further treatment and those given 1% NaCl in the drinking water with subcutaneous injections of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) (25 mg in 0.4 mL of dimethylformamide every fourth day, DOCA-salt rats). SAHA (25 mg·kg−1 dissolved in 80% dimethylformamide) was administered daily as a subcutaneous injection for 32 days, starting 4 days before surgery until experiments. Experiments were performed 28 days after surgery, as in previous studies (Fenning et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Loch et al., 2007).

Assessment of physiological parameters

Body weight, food and water intakes were measured daily. Systolic blood pressure was measured after 0, 2 and 4 weeks under light sedation with i.p. injection of Zoletil (tiletamine 15 mg·kg−1, zolazepam 15 mg·kg−1), using an MLT1010 Piezo-Electric Pulse Transducer (ADInstruments) and inflatable tail-cuff connected to a MLT844 Physiological Pressure Transducer (ADInstruments) and PowerLab data acquisition unit (ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia). Rats were killed with an injection of pentobarbitone sodium (100 mg·kg−1 i.p.). Blood was taken from the abdominal aorta and centrifuged, and the plasma was frozen. Plasma malondialdehyde concentrations were determined by HPLC (Sim et al., 2003).

Isolated heart preparation

The left ventricular function of the rats in all treatment groups was assessed using the Langendorff heart preparation. Terminal anaesthesia was induced via i.p. injection of pentobarbitone sodium 100 mg·kg−1 (Lethabarb ®). Once anaesthesia was achieved, heparin (1000 IU) was injected into the right femoral vein. After allowing 2 min for the heparin to circulate fully, the heart was excised and placed in cooled (4°C) Krebs Henseleit bicarbonate solution [composition (in mM): 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.3 CaCl2, 25.0 NaHCO3, 11.0 glucose].The heart was then attached to the cannula and perfused with the Krebs solution in a non-circulating Langendorff manner at 100 cm of hydrostatic pressure. The buffer temperature was maintained at 35°C. The hearts were punctured at the apex to facilitate thebesian drainage. Isovolumetric ventricular function was measured by inserting a latex balloon catheter into the left ventricle connected to a Capto SP844 MLT844 physiological pressure transducer and Chart software on a Maclab system. All left ventricular end-diastolic pressure values were measured by pacing the heart at 250 beats per minute using an electrical stimulator. After a 10-min stabilization period, end-diastolic pressures were obtained starting from 0 mmHg to 30 mmHg. The right and left ventricles were then separated and weighed. Diastolic stiffness constant (κ, dimensionless) was calculated as in previous studies (Fenning et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Loch et al., 2007).

Microelectrode studies on isolated left ventricular papillary muscles

Terminal anaesthesia was induced via i.p. injection of pentobarbitone sodium 100 mg·kg−1 (Lethabarb®). The thorax was opened quickly, and the heart was removed. The left ventricular papillary muscles were quickly dissected in cold Tyrode physiological salt solution (in mM: 136.9 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2·H2O, 0.4 NaH2PO4·2H2O, 22.6 NaHCO3, 1.8 CaCl2·2H2O, 5.5 glucose, 0.3 ascorbic acid and 0.05 Na2EDTA) bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2. APD at 20%, 50% and 90% of repolarization, action potential amplitude and action potential voltage over time (dV/dtmax) were calculated as in previous studies (Fenning et al., 2005; Woolf et al., 2006). Contractile parameters measured were force of contraction and rate of change of force of contraction (dF/dt).

Organ bath studies

Thoracic aortic rings (approximately 4 mm in length) were suspended in an organ bath chamber with a resting tension of 10mN and bathed in a modified Tyrode solution [composition (mM) 136.9 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.05 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 22.6 NaHCO3, 0.42 NaH2PO4, 5.5 glucose, 0.28 ascorbic acid and 0.1 EDTA], bubbled with carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2) and the temperature maintained at 35 ± 0.5°C. Force of contraction was measured isometrically with Grass FT03C force transducers connected via amplifiers to a Macintosh computer via a MacLab system. Cumulative concentration–response curves were performed for noradrenaline, acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in the presence of a submaximal (approximately 70%) contraction to noradrenaline (Allan et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006).

Organ weights

Rats were killed with an overdose of pentobarbitone and the liver, kidneys and spleen were removed and blotted dry for weighing. Heart weights were obtained from the same animals, after Langendorff perfusion (see above). Organ weights were normalized relative to the body weight at the time of their removal (in mg·g−1).

Histology

Tissues were initially fixed for 3 days in Telly's fixative (100 mL of 70% ethanol, 5 mL of glacial acetic acid and 10 mL of 40% formaldehyde) and then transferred into modified Bouin's fluid (85 mL of saturated picric acid, 5 mL glacial acetic acid and 10 mL of 40% formaldehyde) for 2 days. The samples were then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax. Thin sections (10 µm) of left ventricle were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for determination of inflammatory cell infiltration. Monocytes and macrophages were identified under a high power (100× objective) microscope, by a trained observer, unaware of the treatments. Thick sections (15 µm) were cut, stained with picrosirius red and image analysis under the laser scanning microscope was performed as previously described (Levick et al., 2006; Loch et al., 2006).

Cytokine analysis

Cytokines were detected in rat sera using Proteome Profiler™ Rat Cytokine Array Panel A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with 800 µL of rat sera overnight at 4°C with 15 µL of detection antibody cocktail. After washing, streptavidin-HRP and chemiluminescent detection reagent were added sequentially. Multiple exposures to X-ray film were made for up to 30 min. Densitometric analysis of array images was performed using Java-based ImageJ version 1.40 g from National Institutes of Health. The relative changes in cytokine concentrations between sera from DOCA-salt rats ± SAHA treatment were measured and are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n= 3). The rat proteins that could be monitored by this kit were limited to 29 inflammatory markers: interleukins (1α, 1β, 1ra, 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, 13, 17), TNFα, IFNγ, GMCSF, RANTES, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants (CINC 1-3), interferon-inducible protein (IP10), macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP1α, 3α), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP1), LPS-induced CXC chemokine (LIX), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), monokine induced by IFN-gamma (MIG), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (sICAM), L-selectin, CNTF, thymus chemokine and fractalkine.

In other experiments, we used cultures of human monocyte-derived macrophages. The use of blood and derived cells was reviewed and approved by The University of Queensland Ethics Committee. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from the buffy coat of blood taken from healthy unknown donors (Australian Red Cross Blood Service, Kelvin Grove) using Ficoll-paque density centrifugation (GE Healthcare Bio-Science, Uppsala, Sweden). CD14+ monocytes were positively selected using CD14+ MACS magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA). Monocytes were differentiated to macrophages in complete media (composition; IMDM with 10% FBS, 10 U·mL−1 penicillin, 10 U·mL−1 streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine; Invitrogen), with 104 U·mL−1 (100 ng·mL−1) recombinant human macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) (PeptroTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) at 1.5 × 106 monocytes per mL. The human monocyte-derived macrophages were cultured in complete media (at 37°C, with 5% CO2.) and were supplemented with 50% fresh complete medium containing CSF-1 on day 5 after seeding. The macrophages were harvested by gentle scraping in saline solution and replated for use on day 7. The RayBio® Human Cytokine Antibody Array was used to detect whether treatment with SAHA at 5 or 50 µM for 10h changed the expression of both pro- and active forms of human matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-1, -2, -3, -8, -10 and -13 or tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1, -2 and -4 in culture medium. In addition, gelatin zymography experiments were performed to assess the effect of SAHA at 5–500 µM on purified active human recombinant MMP-2 and -9 activity. Cells were cultured at 37°C, with 5% CO2.

Statistical analysis

All data sets are shown as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Comparisons of findings between groups were made via statistical analysis of data sets using one-way/two-way analysis of variance followed by the Duncan test to determine differences between treatment groups. A P-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Materials

Synthesis of SAHA

A mixture of aniline and suberic acid was melted at 190°C for 10 min and then, after cooling, the suberanilic acid was separated from suberic dianilide by extraction into aqueous KOH before acidification. The suberanilic acid was esterified (EtOH/H2SO4) and subsequently treated with hydroxylamine to produce the hydroxamic acid (SAHA). The product showed no impurities either by reversed phase HPLC, NMR (1H, 13C) spectroscopy or mass spectrometry. Spectral data were in agreement with literature values (Stowell et al., 1995).

Pentobarbitone sodium was obtained through the Science Consumables Store, The University of Queensland. Xylazine and zoletil were obtained from Lyppard Australia Limited, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. DOCA, heparin, noradrenaline, acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA). Noradrenaline, acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside were dissolved in distilled water. DOCA was dissolved in dimethylformamide with mild heating.

Results

General and cardiovascular variables measured

DOCA-salt-treated rats showed an increased water intake and failed to gain weight, as in previous studies (Table 1; Mirkovic et al., 2002; Fenning et al., 2005). SAHA failed to alter body weight or water intake in the DOCA-salt rats; further, UNX rats treated with SAHA also failed to gain weight compared with vehicle-treated rats. There was no change in the food intake among the groups. Systolic blood pressure was increased in DOCA-salt rats when compared with UNX rats and this increase was attenuated by SAHA treatment (Table 1). The DOCA-salt rats showed left and right ventricular hypertrophy (increased LV+septum and RV wet weights) at 4 weeks, compared with UNX rats (Table 1) and this increase in organ weights of both ventricles was attenuated by SAHA treatment. DOCA-salt rats showed increased wet weights of liver, spleen and kidney that were unaltered by SAHA treatment (Table 1). Plasma malondialdehyde concentrations, a measure of oxidative stress, were increased in DOCA-salt rats; this increase was attenuated by SAHA treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiological parameters of uninephrectomized (UNX), UNX and deoxycorticosterone-treated (DOCA), UNX + suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) and DOCA + SAHA-treated rats

| Parameter | UNX (4 weeks) | UNX+SAHA (4 weeks) | DOCA (4 weeks) | DOCA+SAHA (4 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weights (g) | 358 ± 5 (n= 6) | 346 ± 15 (n= 6) | 353 ± 6 (n= 6) | 339 ± 8 (n= 6) |

| Final body weights (g) | 441 ± 6 (n= 6) | 353 ± 12# (n= 6) | 351 ± 8# (n= 6) | 351 ± 12# (n= 6) |

| Daily food intake (g) | 31 ± 3.2 (n= 6) | 21.3 ± 4 (n= 6) | 26.6 ± 4 (n= 6) | 24.2 ± 4 (n= 6) |

| Daily water intake (g) | 62.7 ± 10 (n= 6) | 56.4 ± 7 (n= 6) | 155.9 ± 33.2# (n= 6) | 192 ± 35# (n= 6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 0 weeks | 107 ± 1.3 (n= 6) | 108 ± 3.1 (n= 6) | 108 ± 3.1 (n= 6) | 113 ± 1.6 (n= 6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 2 weeks | 128 ± 0.7 (n= 6) | 126 ± 6.9 (n= 6) | 176 ± 7.3# (n= 6) | 143 ± 4.5* (n= 6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 4 weeks | 135 ± 1.7 (n= 6) | 129 ± 3.0 (n= 6) | 186 ± 3.6# (n= 6) | 160 ± 1.6* (n= 6) |

| Diastolic stiffness constant (κ) | 20.3 ± 0.8 (n= 6) | 17.0 ± 0.6 (n= 6) | 32.3 ± 1.7# (n= 6) | 24.8 ± 0.9* (n= 6) |

| LV+septum (mg·g−1 body wt) | 1.7 ± 0.07 (n= 6) | 2.1 ± 0.04 (n= 6) | 3.1 ± 0.1# (n= 6) | 2.4 ± 0.07* (n= 6) |

| RV (mg·g−1 body wt) | 0.30 ± 0.03 (n= 6) | 0.38 ± 0.01 (n= 6) | 0.51 ± 0.04# (n= 6) | 0.42 ± 0.03* (n= 6) |

| Liver (mg·g−1 body wt) | 34.8 ± 0.9 (n= 6) | 35.1 ± 1.5 (n= 6) | 52.4 ± 1.9# (n= 6) | 48.9 ± 2.1 (n= 6) |

| Spleen (mg·g−1 body wt) | 2.9 ± 0.2 (n= 6) | 3.4 ± 0.3 (n= 6) | 4.4 ± 0.1# (n= 6) | 3.8 ± 0.5 (n= 6) |

| Kidneys (mg·g−1 body wt) | 4.3 ± 0.1 (n= 6) | 4.2 ± 0.2 (n= 6) | 8.5 ± 0.2# (n= 6) | 8.4 ± 0.6 (n= 6) |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −71.1 ± 3.7 (n= 8) | −63.0 ± 0.9# (n= 4) | −74.3 ± 1.7 (n= 9) | −61.3 ± 3.5* (n= 10) |

| Action potential amplitude (mV) | 83.8 ± 5.3 (n= 8) | 56.7 ± 3.2# (n= 4) | 81.1 ± 4.5 (n= 9) | 55.1 ± 3.7* (n= 10) |

| Action potential duration at 20% (ms) | 6.8 ± 1.1 (n= 8) | 11.8 ± 1.6# (n= 4) | 24.5 ± 4.1# (n= 9) | 16.7 ± 1.2* (n= 10) |

| Action potential duration at 50% (ms) | 16.4 ± 2.0 (n= 8) | 22.3 ± 5.8 (n= 4) | 40.5 ± 5.9# (n= 9) | 31.3 ± 2.9# (n= 10) |

| Action potential duration at 90% (ms) | 34.4 ± 3.5 (n= 8) | 44.2 ± 8.5 (n= 4) | 84.2 ± 8.1# (n= 9) | 62.3 ± 5.1* (n= 10) |

| Force of contraction (mN) | 1.1 ± 0.4 (n= 8) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (n= 4) | 0.34 ± 0.01 (n= 9) | 3.8 ± 1.0* (n= 10) |

| Plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration (µmol·L−1) | 19.7 ± 0.7 (n= 5) | 21.0 ± 0.8 (n= 5) | 27.3 ± 0.8* (n= 5) | 24.7 ± 0.3* (n= 5) |

P < 0.05 vs. UNX;

P < 0.05 vs. DOCA. LV mass calculated according to Litwin et al. (1994).

Values are mean ± SEM; number of experiments in parentheses.

LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Rat chemokines and cytokines; MMP activity

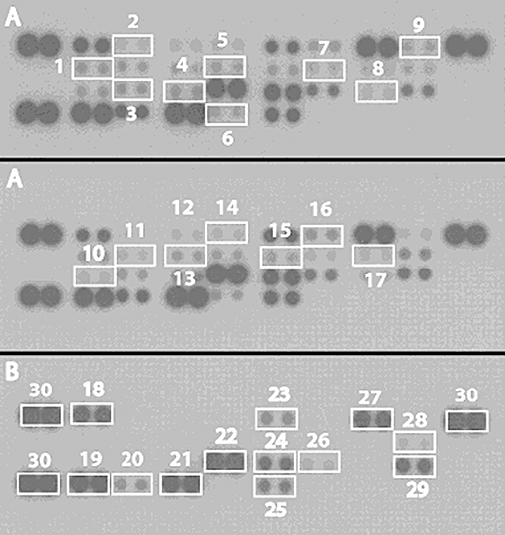

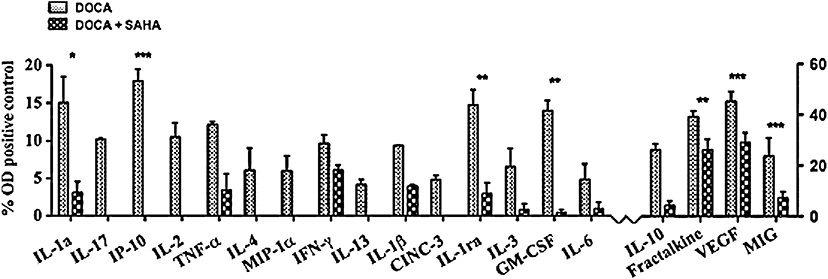

A chemokine/cytokine array kit was used to compare the effect of SAHA on plasma inflammatory mediators from DOCA-salt rats rather than ELISAs for individual cytokines, as cytokines show marked redundancy. As shown in Figure 1, SAHA suppressed the expression of all of these markers, except for CINC1 which was overexpressed, while it was difficult to deduce any change for RANTES, TIMP1 and LIX. Quantitative analysis by densitometry of the blots (Figure 2) could only reliably place statistical significance on the more highly expressed proteins (IL1α, IP10, IL1ra, GMCSF, IL10, fractalkine, VEGF, MIG). We conclude that SAHA has broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory activity in these DOCA-salt-treated rats, by reducing plasma concentrations of a diverse range of pro-inflammatory proteins.

Figure 1.

Suppression of inflammatory cytokines by SAHA treatment in vivo. Serum cytokines from (A) DOCA-treated rats (B) DOCA + SAHA-treated rats. Each blot represents three independent experiments and is numbered 1, IL1a; 2, CINC2a/b; 3, IL17; 4, IP10; 5, IL2; 6, TNFα; 7, IL4; 8, MIP1a; 9, IFNγ; 10, IL13; 11, IL1b; 12, CINC3; 13, IL1ra; 14, CNTF; 15, IL3; 16, GMCSF; 17, IL6; 18, CINC1; 19, RANTES; 20, thymus chemokine; 21, TIMP1; 22, LIX; 23, fractalkine; 24, L-selectin; 25, VEGF; 26, MIG; 27, sICAM; 28, IL10; 29, MIP3; 30 (control).

Figure 2.

Densitometric measurement of relative concentrations in rat plasma of cytokines/chemokines based on % optical density of positive control. Plasma from DOCA and DOCA + SAHA-treated rats. All values are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Further, SAHA is a hydroxamate derivative and, like other hydroxamates (Leung et al., 2000; Halili et al., 2009), could inhibit MMP expression or activity. To address this issue, we measured the expression of human MMPs and TIMPs in culture medium of human monocyte-derived macrophages. Addition of SAHA (5 or 50 µM) did not change MMP expression (data not shown). Further, using gelatin zymography, SAHA at 5 or 50 µM showed no inhibition of MMP-2 and -9 activity whereas at 500 µM, it showed a modest inhibition of MMP-2 activity (data not shown).

Left ventricular structure and function

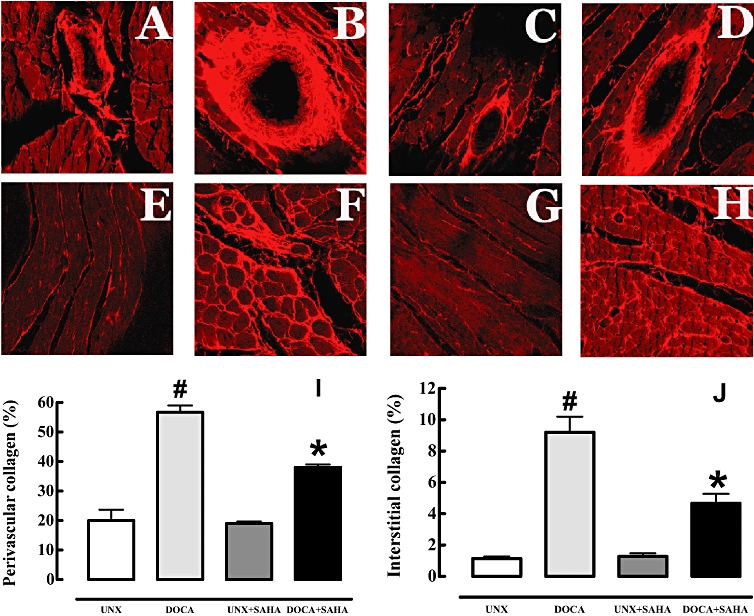

Hearts from DOCA-salt rats showed increased diastolic stiffness that was attenuated by SAHA treatment (Table 1). The collagen content of the left ventricle of UNX rats was increased in DOCA-salt rats (Figure 3) and these increases were attenuated by treatment with SAHA in the DOCA-salt rats. Collagen deposition was unaltered by SAHA treatment in the normotensive UNX rats (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Picrosirius red staining of left ventricular perivascular collagen deposition (A–D) and of left ventricular interstitial collagen deposition (E–H) (magnification, ×40) in UNX (A, E), DOCA (B, F), UNX + SAHA (C, G), DOCA + SAHA (D, H)-treated rats. Summary data (n= 4–5) of the histology are shown below for left ventricular perivascular collagen (I) and interstitial collagen (J) deposition (#P < 0.05 vs. UNX; *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA); collagen is stained light red.

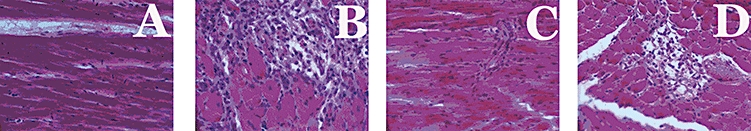

Spatial location of monocyte/macrophages (Figure 4) shows monocyte/macrophages in the left ventricle of UNX rats in very low numbers and always as single cells. The density of monocyte/macrophages found in the left ventricle of DOCA-salt rats was significantly greater than in UNX, and these cells were usually found in clusters of cells located at scar sites and throughout the interstitium and the areas of fibrosis. Very few infiltrating cells were found in scar tissue in DOCA-salt rats treated with SAHA, predominantly due to the decreased area of scar tissue within the left ventricle; few infiltrating cells were found in the perivascular areas (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining of infiltrating inflammatory cells of left ventricular interstitial region (magnification, ×40) in UNX (A), DOCA (B), UNX + SAHA (C), DOCA + SAHA (D)-treated rats.

Microelectrode studies

Single cell microelectrode studies were performed on isolated left ventricular papillary muscles to quantify the changes in electrical conductance in the hypertrophied hearts. In hearts from the DOCA-salt rats, APD was markedly increased at 20%, 50% and 90% of repolarization when compared with UNX hearts. Treatment with SAHA decreased the resting membrane potential and action potential amplitude in both treatment groups (Table 1). The increased APD at 20% and 90% of repolarization in the DOCA-salt rat was reduced by SAHA treatment (Table 1).

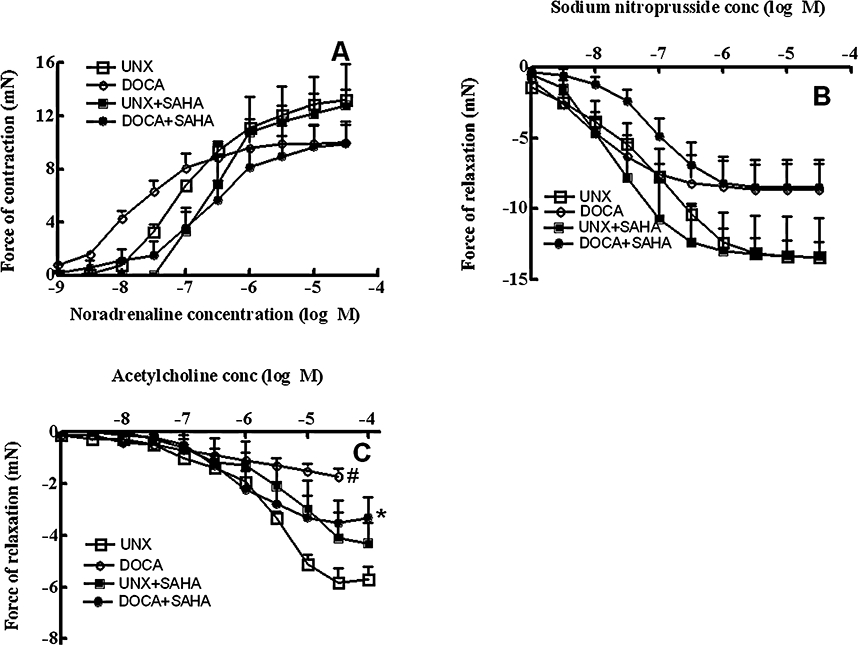

Organ bath studies

Thoracic aortic rings from DOCA-salt rats showed unaltered maximal responses to noradrenaline and sodium nitroprusside across all treatment groups (Figure 5A,B) with minimal relaxation responses to acetylcholine suggesting pronounced endothelial dysfunction (Figure 5C). Treatment with SAHA normalized this decreased response to acetylcholine.

Figure 5.

Cumulative concentration–response curves for noradrenaline (A), sodium nitroprusside (B) and acetylcholine (C) in thoracic aortic rings from UNX, DOCA, UNX + SAHA and DOCA + SAHA-treated rats (#P < 0.05 vs. UNX; *P < 0.05 vs. DOCA).

Discussion

The cardiovascular outcome of chronic pathophysiological stress includes hypertension, hypertrophy and fibrosis, ultimately leading to an enlarged and more rigid myocardium, together with electrical conduction changes and endothelial dysfunction (Weber et al., 1993; Weber, 1996). While HDACi have been reported to be anti-inflammatory (Halili et al., 2009) and to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy (Antos et al., 2003; Kee et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2006; Gallo et al., 2008), we have now shown that the broad spectrum (class I and II) HDACi, SAHA (25 mg·kg−1·day−1), can also attenuate perivascular and interstitial cardiac fibrosis, as well as hypertension, electrical changes and endothelial dysfunction associated with DOCA-salt induced hypertension in rats. Functionally, this decreased fibrosis was associated with markedly reduced cardiac stiffness.

Inflammation is the key initiator of the remodelling of the cardiac extracellular matrix, by allowing the infiltration of inflammatory cells and activating fibroblasts (Nicoletti and Michel, 1999; Rutschow et al., 2006). A single oral dose (0.1–25 mg·kg−1) of SAHA reduced cytokines (TNFα, IL1β, IL6, IFNγ) in the circulation of mice treated with LPS (Leoni et al., 2002). This is in accordance with our findings of diverse cytokine suppression found in DOCA-salt rats after chronic SAHA treatment, and is consistent with a broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory response to SAHA in rats.

Responses to injury in the heart share many features in common with wound healing, inflammation and fibrosis observed in other tissues, including lung, liver, kidney and skin (Kupper and Groves, 1995; Weber, 1997; Zalewski and Shi, 1997; Sime et al., 1998; Friedman, 1999; Brown et al., 2005b). The common sequence of events that occurs in response to an inflammatory insult can be summarized as haemostasis; recruitment of circulating immune-inflammatory cells; macrophage activation; activation of fibroblasts and formation of a provisional matrix; and remodelling of the granulomatous scar (Brown et al., 2005b; Davidson, 1992; Weber, 1996). These responses from activated immune-inflammatory cells are regulated by specific circulating cytokines and growth factors (Brown et al., 2005b). In relation to inflammation and cardiac fibrosis, our previous study showed that a phospholipase A2 inhibitor, KH-064, also markedly attenuated fibrosis in the hypertensive heart without decreasing the infiltration of inflammatory cells (Levick et al., 2006). Other common anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin also decrease collagen deposition and prevent oxidative stress-induced cardiovascular remodelling in infarcted rats and angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats respectively (van Kerckhoven et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2004).

The importance of histone acetylation in the aetiology of cardiac remodelling has been highlighted by the regulation of the hypertrophic response of the heart by selective HDACi (Lu et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2002; Gusterson et al., 2003; Kong et al., 2006). HDACs modulate the divergent stress–response pathways activated during cardiac remodelling (McKinsey and Olson, 2004; Kong et al., 2006). The precise HDAC isoforms responsible for cardiovascular remodelling in vivo are still under discussion, with evidence that class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3, 8 and 11), II (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10) and III (sirtuins) HDACs have pro-hypertrophic, anti-hypertrophic and anti-apoptotic functions in cardiomyocytes respectively (Zhang et al., 2002; Verdin et al., 2003; McKinsey and Olson, 2004; McKinsey and Kass, 2007).

HDACs and pro-inflammatory cytokines have been implicated in a wide variety of inflammatory diseases (Halili et al., 2009), including rheumatoid arthritis (Choo et al., 2008), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Blanchard and Chipoy, 2005), asthma (Bhavsar et al., 2008), inflammatory lung diseases (Adcock et al., 2005; Bhavsar et al., 2008), atherosclerosis, hemorrhagic shock, diabetes, inflammatory bowel diseases, osteoporosis, macular degeneration, neurodegenerative and CNS diseases (Halili et al., 2009), with therapeutic effects of HDACi in many animal models of inflammatory diseases (Blanchard and Chipoy, 2005). SAHA suppressed cytokine production and nitric oxide release both in vivo and in vitro, possibly by regulating the expression of genes that control the synthesis of cytokines and nitric oxide or hyperacetylating other targets (Leoni et al., 2002). There have been relatively few studies where rats have been chronically treated with SAHA. Wise et al. (2008) administered SAHA at oral doses of 0–150 mg·kg−1 as a suspension in water with 1.0% (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose sodium and 0.5% (v/v) polysorbate 80 for up to 14 weeks to test changes in male and female fertility in rats. In the in vivo model of concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury, a model that is TNFα and IL-18 dependent (Faggioni et al., 2000), a single dose of SAHA (50 mg·kg−1) reduced the injury by 50% (Leoni et al., 2002). Oral treatment in mice with SAHA (50 mg·kg−1) for 8 days reduced the clinical and cytokine abnormalities in dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis (Glauben et al., 2006). SAHA was also effective at doses of less than 50 mg·kg−1 as an anti-inflammatory compound in rodent models of rheumatic arthritis, endotoxemia, hepatic injury and colitis (Leoni et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2007). All this in vivo and in vitro information strongly suggests that the dose of SAHA used in this study, 25 mg·kg−1·day−1, is in the range used in previous studies and is an effective dose to show anti-inflammatory effects (Halili et al., 2009).

Inappropriate fibroblast hyperplasia is a hallmark of fibrosis. Myofibroblasts, which are specially differentiated fibroblasts exhibiting contractile properties and expressing smooth muscle a-actin, play an important role in contracture of the granulomatous wound (Brown et al., 2005b). Myofibroblasts have been identified in myocardial scars as the predominant source of collagen (Willems et al., 1994). Macrophages are also localized with myofibroblasts in the nitric oxide-deficient model of fibrosis (Koyanagi et al., 2000) and isoprenaline-induced model of myocardial injury (Nakatsuji et al., 1997). In addition, macrophage infiltration preceded the presence of myofibroblasts and clusters of macrophages were located in close proximity to myofibroblasts (Vyalov et al., 1993), suggesting a role for inflammation in fibroblast activation and differentiation. Further, MMPs are important enzymes in regulating cardiovascular remodelling. Some hydroxamate derivatives inhibit the expression or activity of MMPs (Leung et al., 2000; Halili et al., 2009), but for SAHA we did not observe regulatory effects on the secretion of MMP-1, -2, -3, -8, -9, -10 or -13 or TIMP-1, -2 or -4 into the culture medium of human monocyte-derived macrophages as measured by antibody array. In gelatin zymography experiments, SAHA (5 or 50 µM) had no effect on purified MMP-2 or -9 activities whereas a higher concentration of 500 µM showed a modest inhibition of MMP-2 activity (data not shown). Further, responses to MMP inhibitors differ from those shown with SAHA in this study: thus tetracycline or doxycycline did not change collagen area fraction during post-infarction left ventricular remodelling (Villarreal et al., 2003). This suggests that an anti-inflammatory mechanism for SAHA, reducing circulating cytokines, and thereby reducing infiltrating inflammatory cells and arachidonic acid metabolites, rather than MMP inhibition, may be responsible for the reduced collagen deposition in the perivascular and interstitial areas in the hearts of rats with DOCA-salt hypertension.

Our results also show that treatment with SAHA attenuated the increased wet weights of DOCA-salt hypertensive hearts. As inflammation initiates fibrosis without affecting hypertrophy (Kagitani et al., 2004; Kuwahara et al., 2004), the anti-inflammatory effects of SAHA may have little effect on attenuation of ventricular hypertrophy. Class I HDACs (HDAC 1, 2 and 3) exhibited pro-hypertrophic properties (Verdin et al., 2003; McKinsey and Olson, 2004; McKinsey and Kass, 2007; Trivedi et al., 2007) and also increased cardiac myocyte proliferation during cardiac development in transgenic mice studies (Trivedi et al., 2008). Further, the HDACi, valproic acid, reduced ventricular hypertrophy and remodelling in infarcted rats probably by repressing pro-hypertrophic genes (Lee et al., 2007). This suggests that compounds that inhibit at least class I HDACs attenuate ventricular hypertrophy probably by repressing pro-hypertrophy genes or inducing cell cycle arrest.

Cardiac remodelling induced by DOCA-salt treatment is characterized by a decrease in the expression, current density and function of cardiac potassium channels (Ito and Ik), prolonging the action potential (Momtaz et al., 1996; Capuano et al., 2002). The DOCA-salt rat suffers from cardiac electrical disturbances characterized by an increase in spontaneous arrhythmias (Momtaz et al., 1996; Capuano et al., 2002). This prolongation of the action potential can be markedly attenuated by treatment with the nitric oxide precursor, L-arginine (Fenning et al., 2005) or a selective antagonist of endothelin ETA receptors (Allan et al., 2005) concurrent with decreased cardiac fibrosis. Further, circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα can prolong the action potential by suppressing the delayed rectifier K+ current (Wang et al., 2004). Thus, the improved electrical conductance of the DOCA-salt hearts with SAHA treatment can be attributed to its anti-fibrotic effects.

The increase in systolic blood pressure in the DOCA-salt rats was attenuated with SAHA treatment. Recent studies point to class III HDAC enzymes (sirtuins) as key regulators of vascular endothelial homeostasis controlling angiogenesis, vascular tone and endothelial dysfunction (Potente and Dimmeler, 2008). Although SAHA has been identified as a broad spectrum class I and class II HDACi, it also differentially regulated the sirtuins. In cultured neural cells, SAHA and other class I and II HDACi up-regulated SIRT2, SIRT4 and SIRT7 and down-regulated SIRT1, SIRT5 and SIRT6 gene expression (Kyrylenko et al., 2003). This supports the possibility that improved endothelial function and blood pressure in our study may be due to SAHA modulating the expression of sirtuins, which are vital in vascular endothelial homeostasis.

In summary, our results have shown that at least one HDACi has the potential to suppress cardiac fibrosis during development of hypertension. Although we attribute the observed pharmacological effects to broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory activity, the possibility that the inhibition of global lysine acetylation, which alters various protein complexes and regulators of many major cellular functions including myocardial and vascular cell functions (Choudhary et al., 2009), in being partly responsible cannot be ruled out. The results suggest that modulation of cardiac histone or non-histone protein acetylation by a small molecule HDACi may be a viable approach to targeting intracellular signalling pathways that lead to cardiac remodelling and fibrosis. As the HDACi we have studied here is already used in humans for the treatment of lymphomas, the compound could be further examined in a clinical setting for preventing cardiac remodelling, particularly cardiac fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Red Nutraceuticals Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Australia for providing support to AI. We thank the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council (ARC) for partial financial support of the research and the ARC for a Federation Fellowship to DPF.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CINC

cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor(s)

- IP

interferon-inducible protein

- LIX

LPS-induced CXC chemokine

- MIG

monokine induced by IFN-gamma

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- sICAM

soluble intercellular adhesion molecule

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Adcock IM. HDAC inhibitors as anti-inflammatory agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:829–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock IM, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Histone deacetylation: an important mechanism in inflammatory lung diseases. COPD. 2005;2:445–455. doi: 10.1080/15412550500346683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan A, Fenning A, Levick S, Hoey A, Brown L. Reversal of cardiac dysfunction by selective ET-A receptor antagonism. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:846–853. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos CL, McKinsey T, Dreitz M, Hollingsworth LM, Zhang CL, Schreiber K, et al. Dose-dependent blockade to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28930–28937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar P, Ahmad T, Adcock IM. The role of histone deacetylases in asthma and allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:580–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard F, Chipoy C. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: new drugs for the treatment of inflammatory diseases? Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:197–201. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodelling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005a;45:657–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RD, Mitchell MD, Long CS. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and cardiac extracellular matrix: regulation of fibroblast phenotype. In: Villarreal FJ, editor. Interstitial Fibrosis in Heart Failure. New York: Springer; 2005b. pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Capuano V, Ruchon Y, Antoine S, Sant M, Renaud J. Ventricular hypertrophy induced by mineralocorticoid treatment or aortic stenosis differentially regulates the expression of cardiac K+ channels in the rat. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;237:1–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1016518920693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan V, Hoey A, Brown L. Improved cardiovascular function with aminoguanidine in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:902–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo QY, Ho PC, Lin HS. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: new hope for rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Pharma Des. 2008;14:803–820. doi: 10.2174/138161208784007699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehmann M, Walther TC, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Gervis R, Stecenko A, Dworski R, Lane KB, Loyd JE, Pierson R, et al. Altered prostanoid production by fibroblasts cultured from the lungs of human subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2002;3:17–21. doi: 10.1186/rr166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JM. Wound repair. In: Gallin JI, Goldstein RH, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. New York: Raven Press, Ltd; 1992. pp. 809–819. [Google Scholar]

- Faggioni R, Jones-Carson J, Reed DA, Dinarello CA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C, et al. Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice are protected from T cell-mediated hepatotoxicity: role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2367–2372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040561297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning A, Harrison G, Rose'meyer R, Hoey A, Brown L. L-Arginine attenuates cardiovascular impairment in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:1408–1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00140.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL. Stellate cell activation in alcoholic fibrosis – an overview. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:904–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo P, Latronico MV, Gallo P, Grimaldi S, Borgia F, Todaro M, et al. Inhibition of class I histone deacetylase with an apicidin derivative prevents cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:416–424. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauben R, Batra A, Fedke I, Zeitz M, Lehr HA, Leoni F, et al. Histone hyperacetylation is associated with amelioration of experimental colitis in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:5015–5022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusterson RJ, Jazrawi E, Adcock IM, Latchman DS. The transcriptional co-activators CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 play a critical role in cardiac hypertrophy that is dependent on their histone acetyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6838–6847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halili MA, Andrews MR, Sweet MJ, Fairlie DP. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in inflammatory disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:309–319. doi: 10.2174/156802609788085250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinglais N, Huedes D, Nicoletti A, Manset C, Laurent M, Bariety J, et al. Colocalization of myocardial fibrosis and inflammatory cells in rats. Lab Invest. 1994;70:286–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagitani S, Ueno H, Hirade S, Takahashi T, Takata M, Inoue H. Tranilast attenuated myocardial fibrosis in association with suppression of monocyte/macrophage infiltration in DOCA/salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1007–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki Y, Terasaki F, Okabe M, Hayashi T, Toko H, Shimomura H, et al. Myocardial inflammatory cell infiltrates in cases of dilated cardiomyopathy as a determinant of outcome following partial left ventriculectomy. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:797–802. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee HJ, Sohn IS, Nam KI, Park JE, Qian YR, Yin Z, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylation blocks cardiac hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II infusion and aortic banding. Circulation. 2006;113:51–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kerckhoven R, Kalkman EAJ, Saxena PR, Schoemaker RG. Altered cardiac collagen and associated changes in diastolic function of infarcted rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:316–323. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Tannous P, Lu G, Berenji K, Rothermel BA, Olson EN, et al. Suppression of class I and II histone deacetylases blunts pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;113:2579–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi M, Egashira K, Kubo-Inoue M, Usui M, Kitamoto S, Tomita H, et al. Role of transforming growth factor-b1 in cardiovascular inflammatory changes induced by chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. Hypertension. 2000;35:86–90. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper TS, Groves RW. The IL-1 axis and cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:S62–S66. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12316087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Takeya M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, et al. Hypertensive myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction: another model of inflammation? Hypertension. 2004;43:739–745. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118584.33350.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrylenko S, Kyrylenko O, Suuronen T, Salminen A. Differential regulation of the Sir2 histone deacetylase gene family by inhibitors of class I and II histone deacetylases. CMLS Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1990–1997. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TM, Lin MS, Chang NC. Inhibition of histone deacetylase on ventricular remodelling in infracted rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H968–H977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00891.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni F, Zaliani A, Bertolini G, Porro G, Pagani P, Pozzi P, et al. The antitumor histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid exhibits antiinflammatory properties via suppression of cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2995–3000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052702999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D, Abbenante G, Fairlie DP. Protease inhibitors: current status and future prospects. J Med Chem. 2000;43:305–341. doi: 10.1021/jm990412m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levick S, Loch D, Rolfe B, Reid RC, Fairlie DP, Taylor SM, et al. Antifibrotic activity of an inhibitor of group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Immunol. 2006;176:7000–7007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HS, Hu HY, Chan HY, Liew YY, Huang HP, Lepescheux L, et al. Anti-rheumatic activities of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in vivo in collagen-induced arthritis in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:862–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin SE, Katz SE, Morgan JP, Douglas PS. Serial echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular geometry and function after large myocardial infraction in the rat. Circulation. 1994;89:345–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loch D, Hoey A, Morisseau C, Hammock BO, Brown L. Prevention of hypertension in DOCA-salt rats by an inhibitor of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;47:87–98. doi: 10.1385/cbb:47:1:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loch D, Levick S, Hoey A, Brown L. Rosuvastatin attenuates hypertension-induced cardiovascular remodelling without affecting blood pressure in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:396–404. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000210072.48991.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, McKinsey TA, Nicol RL, Olson EN. Signal-dependent activation of the MEF2 transcription factor by dissociation from histone deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4070–4075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080064097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey TA, Kass DA. Small-molecule therapies for cardiac hypertrophy: moving beneath the cell surface. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:617–635. doi: 10.1038/nrd2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey TA, Olson EN. Cardiac histone acetylation – therapeutic opportunities abound. Trends Genet. 2004;20:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkovic S, Seymour AM, Fenning A, Strachan A, Margolin SB, Taylor SM, et al. Attenuation of cardiac fibrosis by pirfenidone and amiloride in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:961–968. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz A, Coulombe A, Richer P, Mercadier J, Coraboeuf E. Action potential and plateau ionic currents in moderately and severely DOCA-salt hypertrophied rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:2511–2522. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuji S, Yamate J, Kuwamura M, Kotani T, Sakuma S. In vivo responses of macrophages and myofibroblasts in the healing following isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats. Virchows Arch. 1997;430:63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01008018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A, Michel J-B. Cardiac fibrosis and inflammation: interaction with hemodynamic and hormonal factors. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:532–543. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potente M, Dimmeler S. Emerging roles of SIRT1 in vascular endothelial homeostasis. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2117–2122. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe N, Hutchins J, Barry B, Hickey W. Chronic myocarditis induced by T cells reactive to a single cardiac myosin peptide: persistent inflammation, cardiac dilatation, myocardial scarring and continuous myocyte apoptosis. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:359–367. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richon VM. Cancer biology: mechanism of antitumour action of vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:S2–S6. [Google Scholar]

- Rutschow S, Li J, Schultheiss HP, Pauschinger M. Myocardial proteases and matrix remodelling in inflammatory heart disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:646–656. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim AS, Salonikas C, Naidoo D, Wilcken DE. Improved method for plasma malondialdehyde measurement by high-performance liquid chromatography using methyl malondialdehyde as an internal standard. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003;785:337–344. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00956-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sime PJ, Marr RA, Gauldie D, Xing Z, Hewlett BR, Graham FL, et al. Transfer of tumor necrosis factor-a to rat lung induces severe pulmonary inflammation and patchy interstitial fibrogenesis with induction of transforming growth factor-b1 and myofibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:825–832. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell JC, Huot RI, Van Voast L. The synthesis of N-hydroxy-N'-phenyloctanediamide and its inhibitory effect on proliferation of AXC rat prostate cancer cells. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1411–1413. doi: 10.1021/jm00008a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Yin L, Giardina C. Butyrate suppresses Cox-2 activation in colon cancer cells through HDAC inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi CM, Lu MM, Wang Q, Epstein JA. Transgenic overexpression of HDAC3 in the heart produces increased postnatal cardiac myocyte proliferation but does not induce hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26484–26489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803686200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi CM, Luo Y, Yin Z, Zhang M, Zhu W, Wang T, et al. Hdac2 regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response by modulating Gsk3b activity. Nat Med. 2007;13:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E, Dequiedt F, Kasler HG. Class II histone deacetylases: versatile regulators. Trends Genet. 2003;19:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal FJ, Griffin M, Omens J, Dillmann W, Nguyen J, Covell J. Early short-term treatment with doxycycline modulates postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2003;108:1487–1492. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089090.05757.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyalov S, Desmouliere A, Gabbiani G. GM-CSF-induced granulation tissue formation: relationships between macrophage and myofibroblast accumulation. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1993;63:231–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02899267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang H, Zhang Y, Gao H, Nattel S, Wang Z. Impairment of HERG K+ channel function by tumor necrosis factor-a: role of reactive oxygen species as a mediator. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13289–13292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT. Wound healing following myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 1996;19:447–455. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960190602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT. Fibrosis, a common pathway to organ failure: angiotensin II and tissue repair. Semin Nephrol. 1997;17:467–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT, Brilla CG, Janicki JS. Myocardial fibrosis: functional significance and regulatory factors. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:341–348. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Gu J, Peng X, Zang G, Nadler J. Overexpression of 12-lipoxygenase and cardiac fibroblast hypertrophy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(03)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann D, Rutschow S, Van Linthout S, Linderer A, Bücker-Gärtner C, Sobirey M, et al. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase attenuates left ventricular dysfunction by mediating pro-inflammatory cardiac cytokine levels in a mouse model of diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2507–2513. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems IE, Havenith MG, De Mey JG, Daemen MJ. The alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive cells in healing human myocardial scars. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:868–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LD, Spence S, Saldutti LP, Kerr JS. Assessment of female and male fertility in Sprague-Dawley rats administered vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2008;83:19–26. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf P, Lu S, Cornford-Nairn R, Watson M, Xiao X-H, Holroyd S, et al. Alterations in dihydropyridine receptors in dystrophin-deficient cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:H2439–H2445. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00844.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Laplante MA, de Champlain J. Prevention of angiotensin II-induced hypertension, cardiovascular hypertrophy and oxidative stress by acetylsalicylic acid in rats. J Hypertens. 2004;22:793–801. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200404000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski A, Shi Y. Vascular myofibroblasts. Lessons from coronary repair and remodelling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:417–422. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, McKinsey T, Chang S, Antos CL, Hill JA, Olson EN. Class II histone deacetylases act as signal-responsive repressors of cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2002;110:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]