Main Text

To the Editor: We read with great interest the paper by Vandewalle et al.1 that appeared in the December 11, 2009, issue of AJHG. The manuscript reports on a 0.3 Mb recurrent but variable copy number gain in the Xq28 region that is found to be associated with mental retardation (MR). This paper is of special interest to us as scientists working in the field of Xq28-linked disease. However, we would like to make a few comments, which we feel would contribute to the message of the paper. The authors suggest that the effect of the copy number gain is most likely due to the increased expression of GDI1. We think it is important that other genes in the region, and in particular IKBKG, be considered for their potential role in MR. In addition, we think that critical previous work on the LCRs L1 and L2 was not included.

As reported, the 0.3 Mb copy number gain in Xq28 contains 18 genes (although 19 genes are listed in Table 1). Vandewalle et al.1 provided data on the increased expression of GDI1 (GenBank NM_001493 [MIM 300104]). However, they did not analyze the mRNA expression of the other genes in the duplicated region, and abnormal expression of one or several of these genes might contribute to the mental handicap observed in the affected families. Of particular note, the phenotypic features discussed in the paper are common to inactivation of other Xq28 brain disease genes, such as IKBKG (MIM 300248), in which, similar to GDI1, loss-of-function mutations are associated with mental retardation.

IKBKG (GenBank NM_003639.3), also called nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) essential modulator (NEMO/IKKgamma), encodes for NEMO/IKKgamma, a protein that is generally recognized to have an essential role in the NF-κB signaling. The NF-κB pathway controls several cellular and developmental processes, and the timely activation and inactivation of this signaling is essential for NF-κB to function in a controlled manner. Indeed, the NEMO/IKKgamma protein, because of its proven crucial role in the pathway, is tightly regulated at posttranslation levels by sequential protein modification,2 as well as at transcriptional levels by multiple regulatory regions.3,4 In addition, the IKBKG gene is highly expressed in the brain and has a well-documented role in neuronal plasticity and central nervous system (CNS) development.5,6 It has been reported that an imbalanced function of IKBKG affects the regulation of NF-κB signaling in this tissue,5 and when NF-κB is hyperactivated or repressed, a defect of neurite growth in a specific subset of neurons is observed.6 It is noteworthy that such a role of the NF-κB pathway in CNS development was confirmed in three reports appearing in the same issue of AJHG, in which Philippe et al.,7 Mochida et al.,8 and Mir et al.9 identified an NF-κB signaling defect as a cause of MR.

The role of IKBKG in the CNS is strongly supported by human genetic data. Loss-of-function mutations of IKBKG, although lethal in males, cause incontinentia pigmenti (IP [MIM 308300]) in females, a neurocutaneous disorder often associated with mental retardation, psychomotor delay, seizure, spastic paresis, and microcephaly. IP patients may also present cortical necrosis, several white matter abnormalities, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, etc.10,11 A heterozygous exon 4_10 IKBKG deletion is the major genetic defect in IP, caused by recombination between two consecutive medium reiterated 67B (MER67B) repeats, located in intron 3 and downstream to exon 10 of the gene, respectively.12 Nevertheless, missense mutations in IKBKG have also been found in association with severe mental handicap.13 Thus, the notion that IKBKG is involved in MR is generally recognized, and the gene was added to the list of MR genes in 2005.14

In addition, we would like to bring attention to previous work on the two distal LCRs discussed in the manuscript by Vandewalle et al.1 The authors reported that the LCRs (named L1 and L2 on page 809) recombine to cause the copy-number gain observed in their four MR families. Although the authors correctly reported that the two LCRs share a high sequence homology, citing the paper of Aradhya et al.,15 they failed to note the presence of IKBKG and its truncated pseudogene copy (from exon 3 to 10) within the two repeats. It would be of interest for people working in clinical genetics to know whether any of the putative mechanistic recombination affected the IKBKG gene and how many copies of this gene are present in the recombinant alleles.

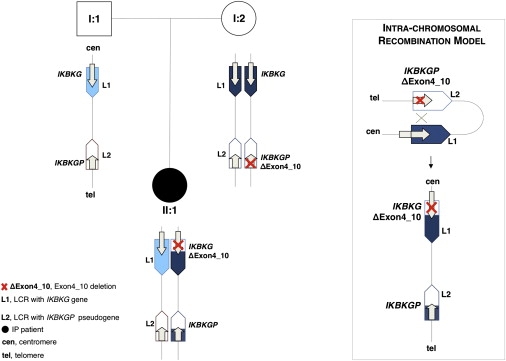

Furthermore, the notion that the L1 and L2 sequence homology causes recombination was extensively documented in the previous reports. Aradhya et al.,15 cited by Vandewalle et al.,1 detected evidence for sequence exchange between the L1 and L2 copies, pointing out that because the two LCR copies are in opposite orientation, inversions might be responsible for their homogeneity. More recently, we reported additional proof of the ability of the LCRs L1 and L2 to recombine.16 Indeed, we observed in IP families a recombination event produced by non-allelic-homology recombination (NAHR) between two LCRs that repositioned an exon4_10 deletion from the pseudogene (IKBKGP, GenBank NG_001576) to the IKBKG gene, thereby causing the IP disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An Example of NAHR between L1 and L2 Causing a Pathological Allele Is Reported: The Case Represents the IKBKG Locus in an IP Family

The unaffected mother (I:2) carrying the exon4_10 deletion in the IKBKGP pseudogene is reported. The IP patient (II:1) carrying the pathogenic deletion in the gene (exon4_10 deletion) is reported.

The misalignment between the two LCRs, L1 and L2, produces the intrachromosomal recombination transferring the exon4_10 del deletion (ΔExon4_10) from the pseudogene to the gene in the recombinant allele.

Vandewalle et al.1 stated that they were unable to clone the breakpoint junctions because of the very high sequence homology between the LCR subunits and the multiple rearrangements that take place between them. We would like to suggest that the authors review our work in which, by using a PCR-based strategy, we mapped the breakpoint in the IP family carrying IKBKG recombinant alleles, which occur by NAHR between L1 and L2.16 We were able to establish that all recombination between LCRs L1 and L2 occur in the MER67B repeats located in intron 3 and downstream exon 10 of the IKBKG gene. Notably, other recurrent intrachromosomal recombination, occurring between two MER67B repeats located within the one individual copy of the LCR, may produce microdeletion-microduplication in the IKBKG gene and pseudogene.16,17

In conclusion, the presence of high-repetitive DNA sequence families, LCRs, and a nonprocessed pseudogene sequence in the Xq28 region is known to enhance homologous recombination. Several previous studies have pointed out the ability of L1 and L2 copies to recombine giving rise to both pathological and nonpathological structural variants of the human genome or copy number variations (CNVs). The recombinant alleles reported by Vandewalle et al.1 fit very well with these previous findings. In addition, we wonder whether any other gene in the duplicated region may play a role in the MR phenotype described by the authors. In particular, we favor the analysis of IKBKG, first of all because it is located exactly in the recombination region, and second, because its nature suggests that any upregulation or decreased expression may cause cellular dysfunction and thus disease in a tissue-specific manner.18

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html?org=Human

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the TELETHON grant GGP08125 to M.V.U. and by Istituto Banco di Napoli-Fondazione.

References

- 1.Vandewalle J., Van Esch H., Govaerts K., Verbeeck J., Zweier C., Madrigal I., Mila M., Pijkels E., Fernandez I., Kohlhase J. Dosage-dependent severity of the phenotype in patients with mental retardation due to a recurrent copy-number gain at Xq28 mediated by an unusual recombination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:809–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebban H., Yamaoka S., Courtois G. Posttranslational modifications of NEMO and its partners in NF-kappaB signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fusco F., Mercadante V., Miano M.G., Ursini M.V. Multiple regulatory regions and tissue-specific transcription initiation mediate the expression of NEMO/IKKgamma gene. Gene. 2006;383:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galgóczy P., Rosenthal A., Platzer M. Human-mouse comparative sequence analysis of the NEMO gene reveals an alternative promoter within the neighboring G6PD gene. Gene. 2001;271:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Loo G., De Lorenzi R., Schmidt H., Huth M., Mildner A., Schmidt-Supprian M., Lassmann H., Prinz M.R., Pasparakis M. Inhibition of transcription factor NF-kappaB in the central nervous system ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:954–961. doi: 10.1038/ni1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez H., O'Keeffe G.W., Gavaldà N., Gallagher D., Davies A.M. Nuclear factor kappa B signaling either stimulates or inhibits neurite growth depending on the phosphorylation status of p65/RelA. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8246–8256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1941-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philippe O., Rio M., Carioux A., Plaza J.M., Guigue P., Molinari F., Boddaert N., Bole-Feysot C., Nitschke P., Smahi A. Combination of linkage mapping and microarray-expression analysis identifies NF-kappaB signaling defect as a cause of autosomal-recessive mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mochida G.H., Mahajnah M., Hill A.D., Basel-Vanagaite L., Gleason D., Hill R.S., Bodell A., Crosier M., Straussberg R., Walsh C.A. A truncating mutation of TRAPPC9 is associated with autosomal-recessive intellectual disability and postnatal microcephaly. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mir A., Kaufman L., Noor A., Motazacker M.M., Jamil T., Azam M., Kahrizi K., Rafiq M.A., Weksberg R., Nasr T. Identification of mutations in TRAPPC9, which encodes the NIK- and IKK-beta-binding protein, in nonsyndromic autosomal-recessive mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fusco F., Bardaro T., Fimiani G., Mercadante V., Miano M.G., Falco G., Israël A., Courtois G., D'Urso M., Ursini M.V. Molecular analysis of the genetic defect in a large cohort of IP patients and identification of novel NEMO mutations interfering with NF-kappaB activation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadj-Rabia S., Froidevaux D., Bodak N., Hamel-Teillac D., Smahi A., Touil Y., Fraitag S., de Prost Y., Bodemer C. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch. Dermatol. 2003;139:1163–1170. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smahi A., Courtois G., Vabres P., Yamaoka S., Heuertz S., Munnich A., Israël A., Heiss N.S., Klauck S.M., Kioschis P., The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. Nature. 2000;405:466–472. doi: 10.1038/35013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebban-Benin H., Pescatore A., Fusco F., Pascuale V., Gautheron J., Yamaoka S., Moncla A., Ursini M.V., Courtois G. Identification of TRAF6-dependent NEMO polyubiquitination sites through analysis of a new NEMO mutation causing incontinentia pigmenti. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2805–2815. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ropers H.H., Hamel B.C. X-linked mental retardation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:46–57. doi: 10.1038/nrg1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aradhya S., Bardaro T., Galgóczy P., Yamagata T., Esposito T., Patlan H., Ciccodicola A., Munnich A., Kenwrick S., Platzer M. Multiple pathogenic and benign genomic rearrangements occur at a 35 kb duplication involving the NEMO and LAGE2 genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2557–2567. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fusco F., Paciolla M., Pescatore A., Lioi M.B., Ayuso C., Faravelli F., Gentile M., Zollino M., D'Urso M., Miano M.G., Ursini M.V. Microdeletion/duplication at the Xq28 IP locus causes a de novo IKBKG/NEMO/IKKgamma exon4_10 deletion in families with Incontinentia Pigmenti. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:1284–1291. doi: 10.1002/humu.21069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson D.L. NEMO, NFkappaB signaling and incontinentia pigmenti. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong E.T., Tergaonkar V. Roles of NF-kappaB in health and disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2009;116:451–465. doi: 10.1042/CS20080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]