Abstract

The pleiotropic lipid mediator sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) can act intracellularly independently of its cell surface receptors through unknown mechanisms. Sphingosine kinase 2 (SphK2), one of the isoenzymes that generates S1P, was associated with histone H3 and produced S1P that regulated histone acetylation. S1P specifically bound to the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 and inhibited their enzymatic activity, preventing the removal of acetyl groups from lysine residues within histone tails. SphK2 associated with HDAC1 and HDAC2 in repressor complexes and was selectively enriched at the promoters of the genes encoding the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 or the transcriptional regulator c-fos, where it enhanced local histone H3 acetylation and transcription. Thus, HDACs are direct intracellular targets of S1P and link nuclear S1P to epigenetic regulation of gene expression.

Phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolites have established roles in signal transduction pathways initiated by activation of cell surface receptors. The recent identification of nuclear lipid metabolism has highlighted a new signaling paradigm for phospholipids. The best characterized of the intranuclear lipids are the inositol lipids that have critical roles in nuclear functions, such as pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, transcriptional regulation, and chromatin remodeling (1). Sphingomyelin has long been known to be a component of the nuclear matrix (2), but the possibility that sphingolipids are also metabolized within the nucleus has only recently emerged from observations that enzymes controlling sphingolipid metabolism, including neutral sphingomyelinase and ceramidase, are also present in the nucleus (3).

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a sphingolipid metabolite that regulates many cellular and physiological processes, including cell growth, survival, movement, angiogenesis, vascular maturation, immunity, and lymphocyte trafficking (4–6). Most of its actions are mediated by binding to a family of five heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptors, designated S1P1–5 (5). S1P may also function inside the cell independently of S1P receptors (4); however, direct intracellular targets of S1P have not been identified. Since the discovery that S1P is produced intracellularly by two closely related sphingosine kinase isoenzymes, SphK1 and SphK2, much has been learned about SphK1 and its functions, yet those of SphK2 remain enigmatic (7).

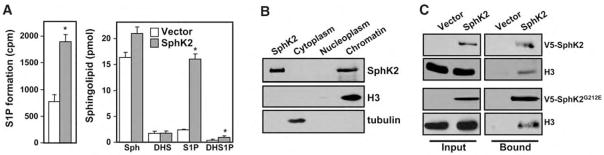

Because, in many cells, SphK2 is mainly localized to the nucleus or can shuttle between the cytosol and the nucleus in accordance with its nuclear localization and export signals (8), we sought to determine its function there (9). In human MCF-7 breast cancer cells, SphK2 is predominantly localized to the nucleus (10), where it is enzymatically active and can produce S1P from sphingosine (Fig. 1A). The nucleus contained high amounts of sphingosine (table S1), and SphK2 expression significantly increased nuclear abundance of S1P by sixfold and dihydro-S1P, which lacks the trans double bond at the 4 position, by twofold (Fig. 1A). Endogenous SphK2 was mainly associated with isolated chromatin and was not detected in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 1B). SphK2 was present in purified mononucleosomes fractionated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, and its distribution paralleled that of native histones (fig. S1A). Thus, we tested whether SphK2 was associated with core histone proteins. Immunoprecipitation of proteins from nuclear extracts prepared from MCF-7 cells overexpressing SphK2 or SphK1 and subsequent Western blot analysis demonstrated that histone 3 (H3) was associated with SphK2 (Fig. 1C), but not with SphK1. H3 was also coimmunoprecipitated with catalytically inactive SphK2G212E (in which glycine 212 is replaced by glutamic acid) (Fig. 1C), which does not increase nuclear S1P (4.4 ± 0.3 and 4.6 ± 0.6 pmol/mg for vector and SphK2G212E, respectively); these findings suggest that enzymatic activity is not required for association of these two proteins. H3 from nuclear extracts also associated with histidine (His)–tagged SphK2 isolated with Ni2+–nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)–agarose beads (fig. S1B). To further confirm the specificity of the physical interaction of SphK2 with H3, we measured in vitro association of Ni-NTA-agarose–bound His-tagged SphK2 or His-SphK1 with individually purified histones. Only H3, but not histones H4, H2B, or H2A, bound to SphK2 (fig. S1C). In contrast, none of the purified histones interacted with SphK1 (fig. S1C).

Fig. 1.

Presence of SphK2 in mononucleosomes and physical association with histone H3. (A) Nuclei were isolated from MCF-7 cells transfected with vector (white bar) or SphK2 (gray bar) and incubated with [3H]sphingosine (1.5 μM) and ATP (1 mM) for 30 min. Formation of [3H]S1P was determined by differential extraction (22). Abundance of sphingoid bases sphingosine (Sph) and dihydrosphingosine (DHS), and their phosphorylated products, S1P and dihydro-S1P (DHS1P), in nuclei of vector and SphK2-expressing MCF-7 cells (7 × 106) were determined by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS). The data are averages of triplicate determinations and are expressed as picomoles of lipid ± SD. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Student’s t test) relative to vector transfectants. (B) Association of SphK2 with chromatin. Equal amounts of cytosol, nucleoplasm, and chromatin fractions from MCF-7 cells were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted with SphK2-specific antibody. Antibodies against H3 and tubulin were used as markers for chromatin and cytosol, respectively. Lysate from MCF-7 cells overexpressing SphK2 was included as a positive control (leftmost lane). (C) Association of SphK2 and histone H3. Proteins of nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells transfected with vector, V5-SphK2, or catalytically inactive V5-SphK2G212E were immunoprecipitated with V5-specific antibody, separated by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies against V5 or H3.

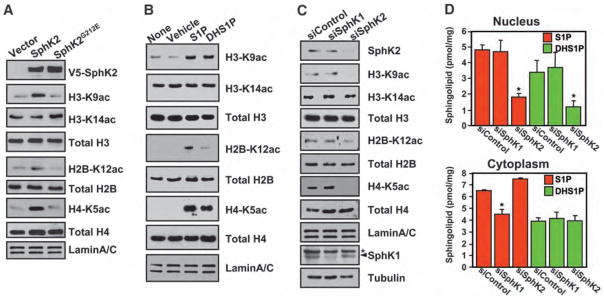

We noticed that expression of SphK2 increased acetylation of lysine 9 of H3 (H3-K9), lysine 5 of histone H4 (H4-K5), and lysine 12 of histone H2B (H2B-K12) (Fig. 2A), without affecting acetylation of other lysines or acetylation of histone H2A. In contrast, expression of catalytically inactive SphK2G212E (Fig. 2A) or SphK1 did not influence acetylation of any residues examined. Although catalytically inactive SphK2G212E also bound to H3 (Fig. 1C), it did not affect its acetylation status (Fig. 2A), which correlated with the formation of S1P in the nucleus with histone acetylation. Addition of S1P or dihydro-S1P, which can both be produced intranuclearly by SphK2 (Fig. 2D), to isolated nuclei also increased specific acetylations of the same lysine residues on histones H3, H4, and H2B without causing acetylation of H2A (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

SphK2 and S1P enhance histone acetylation. (A) Histone acetylation in nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells transfected with vector, V5-SphK2, or catalytically inactive V5-SphK2G212E. Acetylation was detected by immunoblotting with antibodies to specific histone acetylation sites as indicated. (B) Effect of S1P and dihydro-S1P on histone acetylation. Purified nuclei from MCF-7 cells were treated for 5 min without (none) or with vehicle, 1 μM S1P, or 1 μM dihydro-S1P, and histone acetylation was examined by Western blotting. (C and D) Effect of depletion of SphKs. MCF-7 cells were transfected with nontargeting control siRNA, or siRNA targeted to SphK1 or SphK2. (C) Proteins from nuclear extracts were immunoblotted as indicated. Depletion of SphK1 and SphK2 was confirmed by immunoblotting with SphK1-specific and SphK2-specific antibodies, respectively. Asterisk (*) indicates nonspecific band. (D) Amounts of S1P and dihydro-S1P in purified nuclei and cytoplasm quantified by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Student’s t test) relative to control siRNA.

All these results indicate that SphK2 in the nucleus regulates histone acetylation. Depletion of SphK2 with small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Fig. 2C) reduced nuclear but not cytoplasmic amounts of S1P and dihydro-S1P (Fig. 2D), consistent with the specificity of SphK2 for both sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine (11). As expected from its cytosolic localization, siRNA targeted to SphK1 (siSphK1) only reduced amounts of S1P in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2D). siSphK2 specifically decreased acetylation of H3-K9, H4-K5, and H2B-K12, without affecting acetylation of other lysines or acetylation of H2A (Fig. 2C). In contrast, depletion of SphK1 had no significant effect on acetylation of these histone residues (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained with siRNAs targeted to different sequences in SphK2. Addition of S1P to isolated nuclei reversed the decreased acetylation of H3-K9, H4-K5, and H2B-K12 induced by depletion of SphK2 (fig. S2A). siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous SphK2 (fig. S2B), but not that of overexpressed V5-SphK2 (fig. S2C), decreased acetylation of particular histone residues (fig. S2C), which could be reversed by cotransfection with a siRNA-insensitive V5-SphK2 construct (fig. S2C). Together, these observations indicate that S1P produced in the nucleus by endogenous SphK2 acts there to regulate histone acetylation.

Lysine acetylation of histones is a critical component of an epigenetic indexing system demarcating transcriptionally active chromatin domains. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) maintain the delicate, dynamic equilibrium in acetylation levels of nucleosomal histones (12, 13). Neither S1P nor dihydro-S1P increased HAT activity in HeLa cell nuclear extracts, nor did overexpression of SphK2 (fig. S3). In sharp contrast, S1P and dihydro-S1P inhibited HDAC activity in nuclear extracts by 50%, compared with 95% inhibition by the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) (fig. S4A). Conversely, siSphK2, which reduced SphK2 expression by 70% in HeLa cells without affecting SphK1 expression (fig. S4C), enhanced HDAC activity (fig. S4B). This increased HDAC activity was not due to increased abundance of HDAC1 or HDAC2 (fig. S4D). We also assessed the effect of S1P on enzymatic activity of endogenous HDACs. S1P inhibited the enzymatic activity of immunoprecipitated HDAC1 (Fig. 3A) and HDAC2 (fig. S4E) almost as effectively as did TSA. Both S1P and dihydro-S1P also inhibited recombinant HDAC1 (Fig. 3B) and HDAC2 (fig. S4F). However, neither sphingosine nor lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), another bioactive lysophospholipid structurally related to S1P, had significant effects on HDAC1 (Fig. 3B) or HDAC2 activity (fig. S4F). Thus, S1P and dihydro-S1P appear to be endogenous inhibitors of HDAC. To provide further evidence that HDACs are targets for S1P, we examined binding of endogenous HDACs in nuclear extracts to S1P immobilized on agarose beads. Both HDAC1 and HDAC2 were associated with matrices carrying S1P but not by control or LPA matrices (Fig. 3C). In contrast, other class I HDACs (HDAC3, HDAC8), class IIa HDACs (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7), class IIb HDAC (HDAC6), and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)–dependent protein deacetylase SIRT1 did not bind to S1P agarose beads (fig. S5). 32P-labeled S1P specifically bound to either His-tagged HDAC1 or HDAC2 immobilized on Ni-NTA-agarose beads and was displaced by excess unlabeled S1P (fig. S6). Modeling of S1P into the active site of the HDAC1 homolog from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus (14) revealed that it docks well (fig. S7), with a predicted binding energy comparable to that of suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) (fig. S7), a potent inhibitor of HDACs. Indeed, both SAHA and TSA completely displaced bound [32P]S1P from HDAC1 and decreased binding to HDAC2 to a similar extent, as did excess unlabeled S1P (fig. S6). To determine whether endogenous S1P is bound to nuclear HDAC1, we measured the abundance of sphingolipids in HDAC1 immunoprecipitates from nuclear extracts by mass spectrometry. Of all the sphingolipids present in the nucleus, only S1P was bound to HDAC1 (Fig. 3D and table S1). Thus, S1P can bind to the active site of HDAC1 and HDAC2 and inhibit their activity.

Fig. 3.

S1P binds and inhibits HDAC1. (A and B) Effect of S1P and dihydro-S1P on HDAC1 activity. HeLa cell nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with control IgG or HDAC1-specific antibody. Immunoprecipitates were washed, and HDAC activity was measured in the presence of vehicle, 1 μM S1P, 1 μM dihydro-S1P (DHS1P), or 1 μM trichostatin A (TSA). HDAC activities are averages of triplicate determinations ± SD and expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU). (Inset) Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with HDAC1-specific antibody. (B) Activity of recombinant HDAC1 (250 ng) determined in the absence or presence of two concentrations of S1P or dihydro-S1P (0.5 or 5 μM), sphingosine (5 μM), LPA (5 μM), or TSA (1 μM). (C) Association of HDAC with immobilized S1P. Nuclear extracts (NE) from MCF-7 cells were incubated with control (no lipid), LPA, or S1P affinity matrices (as indicated), then washed and bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against HDAC1 or HDAC2. (D) Detection of sphingoid bases. Extracted ion chromatogram for LC-MS/MS reverse-phased separation of sphingoid bases in nuclear extracts (left), or HDAC1-specific antibody (center), and control IgG immunoprecipitates (right). Quantification of sphingosine (Sph) and dihydrosphingosine (DHS), and their phosphorylated products, S1P and dihydro-S1P (DHS1P), is shown in table S1.

HDAC1 and HDAC2 are catalytically active components of distinct multiprotein co-repressor complexes that include Sin3 and NuRD. Over-expressed SphK2 associated with proteins of these co-repressor complexes, mSin3A and MBD2/3, and with HDAC1 and HDAC2 (fig. S8A). Endogenous SphK2 also associated with HDAC1 and HDAC2 and interacted with histone H3 (fig. S8B). These results place SphK2, the enzyme that produces S1P in the nucleus, in close proximity to its potential nuclear targets. To determine whether nuclear S1P levels are regulated in response to external signals and whether HDACs sense these changes, we treated cells with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), an activator of protein kinase C, which enhances phosphorylation and catalytic activity of SphK2 (15). Indeed, PMA increased amounts of S1P in the nucleus by more than twofold within 5 min (fig. S8C) and also rapidly enhanced colocalization of SphK2 with HDAC1 (fig. S9). Prolonged treatment with PMA induced nuclear export of SphK2 (8) (fig. S9), which ensured transient inhibition of HDACs.

A common response to inhibition or depletion of HDAC1 or HDAC2 is the induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 independently of the p53 tumor suppressor protein (16–19). In agreement with possible involvement of SphK2 in p53-independent expression of p21 (10), silencing SphK2 in MCF-7 cells reduced basal and PMA-induced accumulation of p21 protein (fig. S10A) and mRNA (fig. S10B). Overexpression of SphK2, but not catalytically inactive SphK2, enhanced PMA-stimulated transcription of a reporter construct containing the p21 promoter (fig. S10C), and its depletion reduced it (fig. S10D). Overexpression of SphK2 increased acetylation of histone H3-K9 associated with the proximal p21 promoter and further enhanced the response to PMA (Fig. 4A), in accordance with the participation of SphK2 in PMA-induced expression of p21 (fig. S10, A to D). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis also revealed that, like HDAC1, SphK2 is also associated with the proximal p21 promoter (Fig. 4A). Depletion of SphK2 suppressed PMA-induced acetylation of histone H3 at the p21 promoter (Fig. 4C), which further supported the notion that SphK2 regulates HDAC1-dependent deacetylation of histone H3 and repression of p21 gene transcription.

Fig. 4.

SphK2 binding to p21 and c-fos promoters enhances acetylation of histone H3. (A and B) MCF-7 cells transfected with vector, V5-SphK2, or V5-SphK2G212E were treated with vehicle or PMA (100 nM, hatched bars) for 3 hours (A) or 30 min (B) and subjected to ChIP analyses with antibodies to V5, HDAC1, H3-K9ac, or normal rabbit IgG, as indicated. The precipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR with primers amplifying the core promoter sequence of the p21 and c-fos genes. Relative binding to the promoter is expressed as the percentage of input. Data are means ± SD. **P < 0.01, relative to vector transfectants, *P < 0.01, relative to PMA-treated vector transfectants, by Student’s t test. (C and D) MCF-7 cells transfected with control siRNA or siSphK2 were treated with vehicle or PMA (100 nM, hatched bars) for 3 hours (C) or 30 min (D) and subjected to ChIP analyses with antibody against H3-K9ac or with normal rabbit IgG. *P < 0.01, relative to PMA-treated siControl. (E) Model for regulation of histone acetylation and gene transcription by nuclear SphK2 and S1P. PMA stimulates nuclear SphK2, which is associated with specific promoter regions, such as those for p21 and c-fos genes, and increases production of S1P. S1P in turn inhibits HDAC1 and HDAC2, which results in increased acetylation (Ac) of histone(s) and leads to enhanced gene transcription.

We also examined another target gene that shows increased transcription in cells treated with PMA, c-fos (12, 20). SphK2 depletion compromised the induction of endogenous c-fos expression by PMA (fig. S11A) and blocked enhanced c-fos promoter activity (fig. S11B). Overexpression of SphK2, but not that of catalytically inactive SphK2, increased PMA-induced expression of c-fos mRNA (fig. S11C) and enhanced c-fos promoter activity (fig. S11D). Finally, ChIP analysis confirmed the presence of SphK2 on the c-fos promoter and demonstrated that overexpression of SphK2 (but not that of the mutant SphK2 that cannot produce S1P) enhanced H3 acetylation at the c-fos promoter (Fig. 4B). Conversely, down-regulation of SphK2 decreased acetylation of histone H3 at the c-fos promoter in response to PMA (Fig. 4D).

We conclude that HDACs appear to be intra-cellular targets of S1P. Our data reveal a new paradigm of S1P signaling produced by nuclear sphingolipid metabolism, suggesting an important function for SphK2 in the nucleus. Abundance of nuclear S1P may influence specific and contextual chromatin states that impact gene transcription (Fig. 4E). HDACs have emerged as key targets to reverse aberrant epigenetic changes associated with human diseases (18, 21), such as cancer. S1P may therefore influence the delicate balance and dynamic turnover of histone acetylation and the transcription of target genes, linking them to epigenetic regulation in response to environmental signals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH R37GM043880 and R01CA61774 (S.S.). G.S. was supported by National Research Service Award F30NSO58008. S.M. was supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Irvine RF. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:349. doi: 10.1038/nrm1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocco L, Maraldi NM, Manzoli FA, Gilmour RS, Lang A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;96:890. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albi E, Lazzarini R, Viola Magni M. Biochem J. 2008;410:381. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegel S, Milstien S. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:397. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun J, Rosen H. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:161. doi: 10.2174/138161206775193109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1295. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel S, Milstien S. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding G, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 10.Sankala HM, et al. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayton AL, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC. Mol Cell. 2006;23:289. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang XJ, Seto E. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:206. doi: 10.1038/nrm2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finnin MS, et al. Nature. 1999;401:188. doi: 10.1038/43710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hait NC, Bellamy A, Milstien S, Kordula T, Spiegel S. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagger G, et al. EMBO J. 2002;21:2672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gui CY, Ngo L, Xu WS, Richon VM, Marks PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307708100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minucci S, Pelicci PG. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1038/nrc1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dokmanovic M, Clarke C, Marks PA. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:981. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell A, Yang SH, Sharrocks AD. Mol Cell. 2008;29:780. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra P, Payne SG, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Methods Enzymol. 2007;434:257. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)34014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.