Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate how different types of child maltreatment, independently and collectively, impact a wide range of risk behaviors that fall into three domains: sexual risk behaviors, delinquency, and suicidality. Cumulative classification and Expanded Hierarchical Type (EHT) classification approaches were used to categorize various types of maltreatment. Data were derived from Wave III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Our sample consisted of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian females ages 18 to 27 (n = 7,576). Experiencing different kinds of maltreatment during childhood led to an extensive range of risk behaviors within the three identified domains. Women experiencing sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types had the poorest outcomes in all three domains. These findings illustrate that it may no longer be appropriate to assume that all types of maltreatment are equivalent in their potential contribution to negative developmental sequelae.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Child abuse, HIV risk behaviors, Sexual risk behaviors, Delinquency, Suicide, Women, Cumulative approach, Hierarchical approach

Child maltreatment is a complex and serious public health issue. Child maltreatment is associated with the development of various symptoms of psychopathology and health problems (Boxer and Terranova 2008; Higgins and McCabe 2001; Mersky and Reynolds 2007). Specifically, studies have connected various types of maltreatment to sexual risk behaviors (Senn et al. 2008), to delinquency (Lansford et al. 2007; Mersky and Reynolds 2007; Salzinger et al. 2007), and to suicidality (Roy and Janal 2006). However, less attention has focused on comprehensively linking these types of maltreatment, as well as their combinations, with a breadth of subsequent risk behaviors among young women.

The purpose of the current study is to clarify the ways that different types of child maltreatment, independently and collectively, impact a wide range of risk behaviors among women: sexual risk behaviors, delinquency, and suicidality. Women are examined in this study because they are the fastest growing demographic of HIV/AIDS infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007) and the fastest growing subgroup of offenders in the juvenile justice system in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1986, 2007). Women made up only 7% of new HIV/AIDS cases in the US in 1986, however, they accounted for more than 25% of all new diagnoses two decades later (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1986, 2007). During the same period (1986–2006), the total number of juveniles arrested in the US decreased by 700,000 while the rate of female arrests increased from 25 to 29% of total arrests (Snyder 1997, 2006). Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation are also included in this study because women compared to men have a substantially higher prevalence of suicide attempts, including self-inflicted injuries (Chaudron and Caine 2004; Moscicki 1994), despite the fact that men have a higher prevalence of completed suicides. Moreover, each self-inflicted injury results in enormous societal costs: a per person average of $24,353 in hospitalization fees and $57,209 for lost productivity (Corso et al. 2007). Thus, identifying the predictive factors associated with sexual, delinquent, and suicidal behaviors among women is a critical public health issue.

Given the extent of these alarming problems affecting women in multiple risk behavior domains, an examination is needed of ways that child maltreatment impacts a wide range of outcomes. A nationally representative sample of 7,576 White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian women from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) provides an opportunity to examine the connection between experiencing different types and combinations of maltreatment and subsequent sexual risk behaviors, delinquency, and suicidality. This study utilizes cumulative classification and expanded hierarchical type (EHT) approaches to test the relationship between various forms of maltreatment and subsequent risk behaviors among women.

Understanding the Impact of Child Maltreatment on Risk Behaviors

Cumulative Classification Approach

Traditionally, research investigating the impact of child maltreatment on risk behaviors or health has focused on single forms of maltreatment (sexual, physical, or neglect), rather than multiple forms (e.g., physical and sexual; physical and neglect; neglect, physical, and sexual) (Clemmons et al. 2007; Higgins and McCabe 2001). However, growing evidence demonstrates that various forms of child maltreatment often co-occur rather than occurring independently (Arata et al. 2005; Dong et al. 2004; Petrak et al. 2000). Co-occurrence can be simultaneous or sequential over a person's lifetime. Epidemiological studies targeting outpatient and college samples have revealed that the co-occurrence of child maltreatment types ranges from approximately 14 to 30% (Clemmons et al. 2003, 2007). Studies focusing on children from Child Protective Services (CPS) with alleged abuse have substantially high co-occurring rates, which range from 70 to 90% (Claussen and Crittenden 1991; Clemmons et al. 2007; Lau et al. 2005). Considering the high prevalence, it is important to examine the impact of co-occurring types of child maltreatment on multiple domains of outcomes. Much of the evidence has demonstrated that, compared to single type exposure, exposure to co-occurring maltreatment types is associated with more adverse outcomes (Clemmons et al. 2003; Jun et al. 2008; Teicher et al. 2006).

In the developmental literature, studies that focus on co-occurring types of child maltreatment have examined the cumulative effects on various outcomes (Boxer and Terranova 2008; Clemmons et al. 2003; Higgins and McCabe 2001). The cumulative effects approach asserts that, regardless of specific combinations of maltreatment types, the effects of multiple types of maltreatment accumulate and result in severer psychopathology and clinical impairment (Watson et al. 2004) than is seen with fewer types of maltreatment. The underlying mechanism of the cumulative classification approach is that individuals with more childhood adversity may have biological and cognitive changes that may contribute to a lower response threshold to future stressors. Thus, this lower threshold makes these individuals more reactive to adverse experiences, including increased susceptibility to depressive symptoms (Post 1992; Segal et al. 1996).

A substantial number of studies have demonstrated a cumulative effect of maltreatment types (Clemmons et al. 2003; Diaz et al. 2002; Dong et al. 2004). Nevertheless, some studies have shown conflicting findings. For instance, in the context of family violence, the results from a meta-analysis examining 118 studies showed that children who witnessed their parents' physical aggression at home had significantly worse outcomes than children who did not witness their parents' physical aggression. However, there was no significant difference in the outcomes among children who only witnessed aggression compared to children who were physically abused or were both physically abused and witnessed the aggression (Kitzmann et al. 2003).

At this point, there are both practical and conceptual reasons to further clarify the role of the cumulative effects of maltreatment on young women's risk behavior outcomes. First, the majority of studies that tested the cumulative effects of maltreatment, including those studies reviewed in the above meta-analysis, were based on samples that were generally confined to a limited geographical area (Clemmons et al. 2003; Hillis et al. 2001; Jun et al. 2008), limiting their generalizability. Second, as indicated earlier, despite the rapid growth in delinquency rates among women, the relationship between the cumulative experience of multiple maltreatment types and delinquency among young women remains largely unexplored. Thus, analyzing a large and nationally representative sample will shed light on the impact of the cumulative effects of child maltreatment on various outcomes.

Expanded Hierarchical Classification Approach

Using a cumulative approach to understand the impact of co-occurring types of child maltreatment on risk behavior outcomes may be somewhat limited in providing a full picture because this model does not assign any single maltreatment type a greater weight than any other types of maltreatment. However, there might be a hierarchy of maltreatment types, wherein one type of maltreatment compared to other types might be more strongly associated with risk behaviors (Lau et al. 2005). For instance, sexual abuse is considered to be the most detrimental form of abuse for both women and men because it violates the most strongly held social norms (Boxer and Terranova 2008), followed by physical abuse, and finally neglect (Boxer and Terranova 2008; Lau et al. 2005). Herrenkohl and Herrenkohl found in both bivariate and structural equation models (SEM) that sexual abuse was more strongly associated with youths' internalizing and externalizing problems than was physical abuse (Herrenkohl and Herrenkohl 2007). When compared with sexual abuse, neglect was found to have a less robust relationship with risky behavioral outcomes (DePanfilis and Zuravin 2001). Few differences between physical abuse and neglect and their impact on behavioral outcomes have been observed. However, studies have shown that physical abuse compared with neglect has a slightly stronger impact on delinquency and violence outcomes (Mersky and Reynolds 2007). Drawing from this research, an argument can be made that sexual abuse is the severest form of maltreatment, and thus highest on the hierarchy, followed by physical abuse and neglect.

A more systematic approach is needed to identify the hierarchy within single and co-occurring maltreatment types. For instance, Lau et al. used an Expanded Hierarchical Type (EHT) system to differentiate single types of maltreatment from specific combinations of maltreatment types in order to test the validity of different types/combinations in predicting developmental outcomes among a sample of 519 children (Lau et al. 2005). The EHT system classified maltreatment types in the following way: neglect only, physical abuse only, sexual abuse only, emotional maltreatment only, physical abuse plus neglect, and sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types. First, Lau el al. found that EHT had a greater utility in predicting developmental outcomes than the hierarchical type (HT) system, which classified maltreatment as neglect only, any physical abuse, and any sexual abuse. Second, with their data, the researchers were able to clarify the conceptual hierarchy within the types of maltreatment: compared with neglect only, sexual abuse, when combined with physical or other types of abuse had a stronger association with externalizing problems, anger, and post traumatic stress symptoms. Moreover, physical abuse plus neglect was associated with greater post traumatic stress symptoms than neglect only.

However, since Lau et al. only focused on child protective service case records from a convenience sample of 519 children in grades 4 through 8 with a history of alleged maltreatment, it is important to test this EHT system in a different population. Replication of methods used by Lau and colleagues, specifically the EHT system, with a sample of young women will help us test whether sexual abuse combined with other maltreatment types is most strongly associated with multiple risk behaviors. The strength of the EHT system is that it allows us to isolate the independent effect of the co-occurring maltreatment types from single types of maltreatment. Thus, our second research question examines whether different types of abuse, and particular combinations of abuse that are higher on the hierarchy scale, contribute to more negative outcomes in a broad set of risk behaviors.

Hypotheses

Given the complexities surrounding the classification of child maltreatment, both cumulative classification and expanded hierarchical type (EHT) classification approaches were tested to clarify the role of different types of child maltreatment in risk behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesize that a history of more types of maltreatment will be associated with a greater diversity and stronger association with risk behavior domains, when compared to a history of fewer types of maltreatment. We also hypothesize that a history of sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types will be associated with a greater diversity and stronger association with risk behaviors, compared to other combinations of maltreatment. The results of this study will help discern optimal programmatic strategies to develop effective intervention plans for women who experienced child maltreatment.

Method

Demographic Characteristics

Our sample consisted of sexually experienced young adult White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian females (see Table 1). The majority of the sample (68.9%) was White; 16.7% were Black, 9.8% were Hispanic, and 4.6% were Asians. The majority of participants were high school graduates and beyond (87.8%). In terms of sexual risk outcomes, approximately one in ten (n = 900) had at least one STD in the past 12 months. Approximately one fourth of participants reported that they had more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months. In terms of delinquency, approximately 15% of women reported gang affiliation in the past 12 months, and one in ten reported running away from home in their lifetime. Approximately 3–5% of these women reported having been involved in fighting, property damage, selling drugs, and owning guns respectively, in the past 12 months. Approximately 7% of these women reported having suicidal ideation in the past 12 months and 2% reported attempting suicide in the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Number and percent distribution of young women, by background characteristics, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 2001 (n = 7,576)

| n (or mean) Total = 7,576 | % (or 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Race | ||

| White | 4,482 | 68.9% |

| Black | 1,693 | 16.7% |

| Latino | 923 | 9.8% |

| Asian | 478 | 4.6% |

| Age | ||

| 18–21 | 2,999 | 44.0% |

| 22–27 | 4,601 | 56.0% |

| Education level | ||

| Up to 8th grade | 46 | 0.9% |

| Some high school | 783 | 11.2% |

| High school graduate & beyond | 6,766 | 87.9% |

| Depressive symptoms | 4.87 | 4.69–5.05 |

| Sexual risk behaviors | ||

| STD diagnosis | 900 | 12.1% |

| Sexual regret after alcohol use | 848 | 11.7% |

| Multiple sex partners | 1,837 | 27.0% |

| Sex for money | 170 | 2.1% |

| Sex before age 15 | 1,169 | 16.5% |

| Delinquency | ||

| Property damage | 319 | 4.2% |

| Selling drugs | 269 | 4.1% |

| Fighting | 237 | 3.1% |

| Gang affiliation | 1,162 | 14.6% |

| Owning gun | 332 | 4.7% |

| Ever runaway | 738 | 9.7% |

| Suicidality | ||

| Suicidal ideation | 136 | 6.6% |

| Suicidal attempt | 46 | 2.1% |

All percentages are weighted

Data Source

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) provided the original data for this study through Wave I (1995) and Wave III (2001) in-home interviews. Add Health's original objective was to provide information on general, mental, and sexual and reproductive health. The sampling design and procedures have been described extensively elsewhere (Bearman et al. 1997; Miller et al. 2004; Resnick et al. 1997). Confidentiality was ensured through the use of Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (A-CASI) software and laptop computers for the collection of sensitive information (i.e. sexual or deviant behavior). It has been shown that A-CASI technology helps to increase the reporting of sexual behavior (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2004). Add Health included three periods of data collection, for which the same individuals were interviewed during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: Wave I (1994–1995), Wave II (1995–1996), and Wave III (2001–2002).

Measures

Three measures were used to determine childhood maltreatment from the Wave III interview. Add Health included questions regarding neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, and the following method of classifying single types of maltreatment was used in a prior study (Shin et al. 2009).

Child Maltreatment

The child maltreatment questions were introduced as follows: “The next set of questions is about your parents or other adults who took care of you before you were in the 6th grade. How often had each of the following things happened to you by the time you started 6th grade?”

Neglect

This variable was assessed by two items, “By the time you started 6th grade, how often had a caregiver not taken care of your basic needs, such as keeping you clean or providing food or clothing?”, and “How often had he/she left you home alone when an adult should have been with you?” All responses were coded into two categories (never or 1 or more times).

Physical abuse

This variable was measured with the question, “how often had a caregiver slapped, hit, or kicked you?” All responses were dichotomized.

Sexual abuse

This variable was assessed with the question, “by the time you started 6th grade, how often had one of your parents or other adult caregivers touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sexual relations?” All responses were dichotomized (1 for one or more times, 0 for never).

To calculate the co-occurrence of the various forms of child maltreatment based on the cumulative classification approach, the total number of maltreatment types was added. Participants were assigned a score ranging from 0 = “no maltreatment” to 3 = “all three types of maltreatment.” Second, to calculate the co-occurrence of child maltreatment based on Lau et al. (2005) expanded hierarchical type (EHT) system, participants were categorized in the following way: those who experienced (1) neglect only; (2) physical abuse only; (3) sexual abuse only; (4) physical abuse plus neglect (this criterion does not include “physical abuse only” and “neglect only”); (5) sexual abuse plus another maltreatment type (this criterion does not include “sexual abuse only”).

Demographic Variables

These demographic variables were controlled for in the analyses.

Race

This measure was coded as White, Black, Latino, or Asian.

Age

This measure was coded as 18–21 or 22–27 years old.

Educational level

This measure was coded as up to 8th grade, some high school, and high school graduate and beyond.

Depressive symptoms

This measure was measured using a modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). Wave III has 9 of the original 20 items from the CES-D: (1) you were bothered by things that usually don't bother you; (2) you could not shake off the blues, even with help from your family and your friends; (3) you felt that you were just as good as other people; (4) you had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing; (5) you were depressed; (6) you were too tired to do things; (7) you enjoyed life; (8) you were sad; and (9) you felt that people disliked you. Each statement is scored from 0 to 3 with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this study sample was 0.82.

Sexual Risk Behaviors

Five outcomes were used to measure various areas of sexual risk behaviors.

STD diagnosis

STD diagnosis was used measured as follows, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or nurse that you had…?” For each of the following STDs: chlamydia, syphilis, gonorrhea, HIV/AIDS, genital herpes, genital warts, trichomoniasis, and human papilloma virus.

Sexual regret after alcohol use

This was measured by the question, “How many times did you get into a sexual situation that you later regretted because you had been drinking?”

Multiple sex partners

This was assessed by the question, “With how many different partners have you had vaginal intercourse in the past 12 months?” (Having more than one sex partner in the past 12 months was coded as 1, and having no or one sex partner was coded as 0.)

Sex for money

This was measured using one item, “Have you ever had sex with someone who paid you to do so?”

Sex before age 15

This was assessed by the item, “How old were you the first time you had vaginal intercourse?” Each question was dichotomized.

Delinquency

Six outcomes were used to measure various areas of delinquency.

Property damage

This was assessed using one item, “In the past 12 months, how often did you deliberately damage property that didn't belong to you?”

Selling drugs

This was measured using one item, “In the past 12 months, how often did you sell marijuana or other drugs?”

Fighting

This was assessed by the question, “In the past 12 months, how often did you take part in a physical fight where a group of your friends was against another group?”

Gang affiliation

This was measured using one item, “Have you ever belonged to a named gang?”

Owning gun

This was measured by the item, “Do you own a handgun? Don't count a gun you must have for your job.”

Ever runaway

This was measured by the question, “Have you ever run away from home?” Each question was also dichotomized.

Suicidality

Two outcomes were used to measure suicidality.

Suicidal ideation

This was measured by the item, “During the past 12 months, have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?”

Suicidal attempt

This was measured using one item, “During the past 12 months, how many times have you actually attempted suicide?” In the analyses reported here, responses for all outcomes were dichotomized.

Results

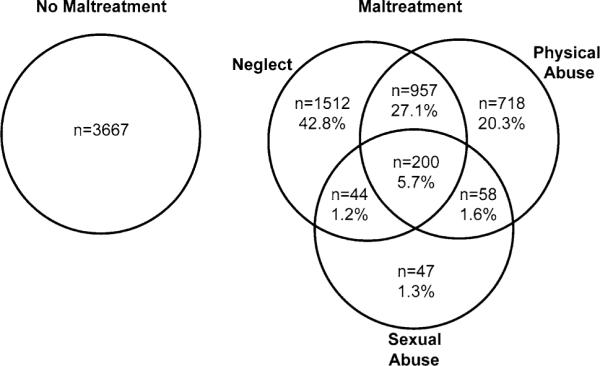

Overall, the present study found that approximately half of young women in the US have reported some type of child maltreatment. Within the group of participants with some history of maltreatment (n = 3536), neglect only was found to be the most common form of maltreatment (42.8%). One in five participants reported having physical abuse only (n = 718), and 1.3% reported a history of sexual abuse only. Of participants reporting co-occurring maltreatment types, those who reported neglect plus physical abuse had the highest proportion (27.1%, n = 957). Roughly 6% (n = 200) reported all three forms of maltreatment.

Tables 2 and 3 test our first hypothesis: a history of more types of maltreatment is associated with higher sexual risk, delinquency, and suicidality. Table 2 shows that approximately one third of participants reported one type of maltreatment. Approximately 15% of participants reported that they had experienced two or more types of maltreatment, demonstrating that experiencing multiple types of maltreatment was less common than experiencing single types of maltreatment. We observed consistent patterns in the relationship between the number of types of maltreatment and sexual, delinquent, and suicidal outcomes, namely that the more types of maltreatment a woman experienced, the higher the proportion of all the outcomes the woman reported. Among the sexual risk outcomes, women with no maltreatment reported the lowest proportions (STD diagnoses, 9%; sex for money, 1.3%; having multiple sex partners, 22.9%; this is compared to 14, 1.9, and 30% respectively for those reporting one type of maltreatment). Women reporting three types of maltreatment also reported the highest proportion of sexual risk outcomes, ranging from 9.6% (sex for money) to 38.2% (multiple sex partners).

Table 2.

Proportion of risk behavioral outcomes according to the number of types of maltreatment: based on the cumulative classification approach

| No maltreatment (95% CI) | One type of maltreatment (95% CI) | Two types of maltreatment (95% CI) | Three types of maltreatment (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 3,667 51.6% |

n = 2,277 31.6% |

N = 1,059 14.3% |

n = 200 0.3% |

||

| Sexual risk behavior | |||||

| STD diagnosis | 9.0% (7.8–10.5) | 13.6% (11.7–15.6) | 17.2% (14.0–20.9) | 20.9% (14.6–28.7) | 0.0000 |

| Sexual regret after alcohol use | 9.6% (7.9–11.5) | 13.8% (11.8–16.0) | 14.4% (11.5–17.8) | 20.0% (13.2–29.2) | 0.0001 |

| Multiple sex partners | 22.9% (20.6–25.3) | 30.2% (27.3–33.2) | 30.8% (26.9–35.1) | 38.2% (28.8–48.5) | 0.0000 |

| Sex for money | 1.3% (0.8–2.0) | 1.9% (1.3–2.8) | 3.4% (2.1–5.4) | 9.6% (5.2–17.2) | 0.0000 |

| Sex before age 15 | 13.3% (11.5–15.3) | 17.8% (15.2–20.7) | 21.8% (18.7–25.1) | 33.9% (24.9–44.4) | 0.0000 |

| Delinquency | |||||

| Property damage | 2.5% (1.9–2.5) | 5.5% (4.4–6.9) | 6.5% (4.9–8.7) | 9.6% (5.6–16.0) | 0.0000 |

| Selling drugs | 2.9% (2.1–3.9) | 4.7% (3.5–6.2) | 5.7% (4.0–8.2) | 10.0% (5.4–17.5) | 0.0005 |

| Fighting | 1.8% (1.2–2.7) | 4.4% (3.3–5.8) | 4.4% (3.1–6.4) | 7.1% (3.9–12.7) | 0.0000 |

| Gang affiliation | 13.4% (12.0–15.0) | 15.3% (13.4–17.5) | 14.0% (11.3–17.1) | 31.7% (23.3–41.4) | 0.0000 |

| Owning gun | 4.5% (3.5–5.8) | 4.8% (3.6–6.4) | 4.4% (3.0–6.6) | 14.2% (8.5–22.7) | 0.0009 |

| Runaway | 5.8% (4.5–7.4) | 8.9% (7.3–10.7) | 19.7% (16.4–23.5) | 29.0% (21.0–38.5) | 0.0000 |

| Suicidality | |||||

| Suicidal ideation | 3.9% (3.0–5.0) | 6.9% (5.3–8.9) | 13.4% (10.8–16.4) | 20.6% (13.6–30.0) | 0.0000 |

| Suicidal attempt | 1.4% (9.1–2.0) | 2.1% (1.3–3.3) | 4.1% (2.7–6.1) | 6.9% (3.5–13.2) | 0.0000 |

All percentages were weighted

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) from multivariate analyses assessing association between the number of types of maltreatment and risk Behavioral Outcomes: based on the cumulative classification approach

| No maltreatment (95% CI) | One type of maltreatment (95% CI) | Two types of maltreatment (95% CI) | Three types of maltreatment (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 3,667 51.6% |

n = 2,277 31.6% |

n = 1,059 14.3% |

n = 200 0.3% |

|

| Sexual risk behaviors | ||||

| STD diagnosis | 1 | 1.4 (1.21–1.70)*** | 1.9 (1.58–2.37)*** | 2.3 (1.57–3.30)*** |

| Sexual regret after alcohol use | 1 | 1.5 (1.25–1.75)*** | 1.6 (1.31–2.01)*** | 2.3 (1.55–3.36)*** |

| Multiple sex partners | 1 | 1.4 (1.25–1.62)*** | 1.5 (1.28–1.78)*** | 2.4 (1.71–3.22)*** |

| Sex for money | 1 | 1.4 (0.91–2.02) | 2.0 (1.29–3.09)** | 3.6 (1.93–6.64)*** |

| Sex before age 15 | 1 | 1.4 (1.20–1.62)*** | 1.6 (1.36–1.98)*** | 2.3 (1.64–3.21)*** |

| Delinquency | ||||

| Property damage | 1 | 1.6 (1.19–2.11)** | 2.5 (1.82–3.42)*** | 2.6 (1.51–4.43)*** |

| Selling drugs | 1 | 1.6 (1.14–2.10)** | 1.8 (1.24–2.57)** | 3.5 (2.06–5.98)*** |

| Fighting | 1 | 2.4 (1.73–3.41)*** | 2.8 (1.93–4.14)*** | 3.0 (1.63–5.58)*** |

| Gang affiliation | 1 | 1.2 (0.96–1.30) | 1.1 (0.94–1.38) | 2.5 (1.79–3.42)*** |

| Owning gun | 1 | 1.0 (0.80–1.35) | 0.9 (0.64–1.33) | 3.7 (2.36–5.88)*** |

| Ever runaway | 1 | 1.5 (1.22–1.83)*** | 2.9 (2.30–3.56)*** | 4.0 (2.76–5.67)*** |

| Suicidality | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 1.4 (1.06–1.76)* | 2.7 (2.07–3.51)*** | 3.9 (2.55–5.90)*** |

| Suicidal attempt | 1 | 0.9 (0.56–1.45) | 2.1 (1.34–3.28)** | 2.9 (1.51–5.71)** |

Analysis controlled for race, age, education level, and depressive symptoms

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Consistent with the relationship between maltreatment and sexual risk outcomes, women who experienced no maltreatment reported lower proportions of all of the delinquency outcomes. The proportion of these risk behavior outcomes incrementally increased with the number of types of maltreatment. Specifically, of women who experienced no type of maltreatment, 1.8% reported fighting, 2.9% of selling drugs, 5.9% of having run away from home, and 13.4% of having a gang affiliation. Of those who experienced three types of maltreatment, 7.1% reported fighting, 10% reported selling drugs, 29% reported having run away from home, and 32% reported gang affiliation. Notably, similar patterns were observed in both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The Sample Characteristics based on Child Maltreatment History (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 2001)

After controlling for race, age, education, and depressive symptoms, history of child maltreatment was independently associated with sexual, delinquent, and suicidal outcomes. Similar to the findings from the bivariate analyses, these multivariate results also demonstrate the incremental increase of odds ratios as the number of types of maltreatment increases. Having a history of one type of maltreatment was significantly associated with 9 of 13 outcomes: four sexual risk behaviors (odds ratios ranged from 1.4 to 1.5), four delinquency outcomes (odds ratios ranged from 1.5 to 2.4), and suicidal ideation (odds ratio 1.4). Having a history of two types of maltreatment was significantly associated with 11 of 13 outcomes: five sexual risk behaviors (odds ratios ranged from 1.5 to 2.0), four delinquency outcomes (odds ratios ranged from 1.8 to 2.9), and both suicidal behaviors (odds ratios ranged from 2.1 to 2.7). Having a history of three types of maltreatment was significantly associated with all 13 outcomes: five sexual risk behaviors (odds ratios ranged from 2.3 to 3.6), six delinquency outcomes (odds ratios ranged from 2.5 to 4.0), and both suicidality behaviors (odds ratios ranged from 2.9 to 3.9).

Table 4 shows the proportion of sexual risk, delinquency, and suicidal behaviors associated with types of maltreatment based on the expanded hierarchical type (EHT) system. History of child maltreatment was categorized as six different types: (1) no maltreatment, (2) neglect only, (3) physical abuse only, (4) sexual abuse only, (5) physical abuse plus neglect, and (6) sexual abuse plus other maltreatment. As hypothesized, women who had sexual abuse plus other maltreatment had the highest proportion in every single outcome except two sexual risk behavior outcomes (STD diagnosis and sexual regret after alcohol use) and one delinquency outcome (selling drugs). In contrast, those with no history of maltreatment generally had the lowest proportion of most outcomes across all three domains. Among those who reported a single type of maltreatment, the patterns of association between those single types of maltreatment and the outcome variables were not clear enough to establish a definitive hierarchy among single types of maltreatment. However, women with co-occurring maltreatment types reported substantially higher risk behaviors than women who experienced single types of maltreatment only. Compared to experiencing physical abuse plus neglect, experiencing sexual abuse plus other maltreatment (either neglect or physical) had a higher proportion of associations with all outcome variables. These results provide evidence that sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types is the most detrimental combination, supporting the EHT model.

Table 4.

Prevalence of risk behavioral outcomes according to the types of maltreatment based on expanded hierarchical type (EHT)

| No maltreatment | Neglect only | Physical abuse only | Sexual abuse only | Physical abuse plus neglect | Sexual abuse plus other maltreatment | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 3,667 51.6% |

n = 1,512 21.2% |

n = 718 9.9% |

n = 47 0.5% |

n = 957 13.0% |

n = 302 3.8% |

||

| Sexual risk behaviors | |||||||

| STD diagnosis | 9.0% (7.8–10.5) | 13.3% (11.1–15.7) | 13.1% (9.9–17.1) | 35.3% (17.0–59.2) | 17.2% (13.8–21.2) | 19.5% (14.7–25.4) | 0.0000 |

| Sexual regret after alcohol use | 9.6% (7.9–11.5) | 13.8% (11.5–16.5) | 13.4% (10.7–16.8) | 20.6% (7.1–46.7) | 14.0% (11.0–17.6) | 19.4% (14.0–26.1) | 0.0003 |

| Multiple sex partners | 22.9% (20.6–25.3) | 28.9% (25.5–32.6) | 32.8% (28.5–37.3) | 22.9% (35.9–59.3) | 30.3% (26.2–34.7) | 37.5% (29.8–45.8) | 0.0000 |

| Sex for money | 1.3% (0.8–2.0) | 2.0% (1.3–3.2) | 1.8% (1.0–3.5) | 0.8% (0.1–6.2) | 3.4% (2.1–5.4) | 7.6% (0.8–2.0) | 0.0000 |

| Sex before age 15 | 13.3% (11.5–15.3) | 17.5% (14.9–20.5) | 18.0% (13.8–23.0) | 23.5% (9.6–47.2) | 21.7% (18.4–25.3) | 30.3% (22.5–38.7) | 0.0000 |

| Delinquency | |||||||

| Property damage | 2.5% (1.9–3.2) | 4.9% (3.5–6.7) | 7.1% (5.1–9.8) | 1.9% (0.3–12.4) | 6.5% (4.8–8.9) | 8.9% (5.4–13.4) | 0.0000 |

| Selling drugs | 2.9% (2.1–3.9) | 4.3% (2.9–6.2) | 5.4% (3.7–7.9) | 8.5% (1.4–37.5) | 6.1% (4.2–8.7) | 7.3% (4.0–12.8) | 0.0065 |

| Fighting | 1.8% (1.2–2.7) | 4.0% (2.8–5.7) | 5.2% (3.4–7.9) | 3.3% (1.0–18.3) | 4.4% (3.0–6.4) | 6.5% (3.8–10.7) | 0.0001 |

| Gang affiliation | 13.4% (12.0–15.0) | 16.5% (14.0–19.2) | 12.9% (9.8–16.9) | 15.6% (5.3–37.7) | 14.3% (11.4–17.8) | 24.4% (18.3–31.7) | 0.0061 |

| Owning gun | 4.5% (3.5–5.8) | 5.6% (4.0–7.9) | 3.1% (1.9–5.1) | 0.2% (0.03–1.5) | 4.3% (2.8–6.5) | 11.2% (6.9–17.6) | 0.0020 |

| Ever runaway | 5.8% (4.5–7.4) | 9.0% (7.1–11.3) | 8.8% (6.4–12.1) | 3.9% (1.0–18.3) | 19.5% (16.1–23.4) | 26.6% (20.4–33.9) | 0.0000 |

| Suicidality | |||||||

| Suicidal ideation | 3.9% (3.0–5.0) | 5.5% (4.0–7.4) | 10.1% (7.1–14.2) | 1.9% (0.3–13.4) | 12.3% (10.0–15.3) | 21.6% (15.8–28.9) | 0.0000 |

| Suicidal attempt | 1.4% (0.9–2.0) | 1.9% (0.6–2.0) | 4.3% (2.5–7.6) | 0 | 3.9% (2.5–6.0) | 6.7% (3.9–11.5) | 0.0000 |

All percentages were weighted. (95% CI)

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

In Table 5, we used multiple logistic regression models to examine the correlates of types of maltreatment (no maltreatment, neglect only, physical abuse only, sexual abuse only, physical abuse plus neglect, and sexual abuse plus other maltreatment) and three domains of risk behaviors. Similar to the results from the bivariate analysis (Table 4), history of sexual abuse plus other maltreatment was significantly associated with every single outcome even after controlling for race, age, educational level, and depressive symptoms. In addition to the significant associations between sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types and all 13 outcomes, this combination had the highest odds ratios in 12 out of 13 outcomes. The STD diagnosis outcome had a stronger association with sexual abuse only, compared to sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types. Physical abuse plus neglect was significantly associated with 11 out of 13 outcomes; physical abuse only was associated with 9 out of 13 outcomes; neglect only was associated with 7, and sexual abuse only with one. These results provide additional evidence that a hierarchy exists among types of maltreatment: a history of sexual abuse plus other maltreatment had the strongest association with all three risk behavior domains followed by physical abuse plus neglect, physical abuse only, neglect only, and sexual abuse only, respectively.

Table 5.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) from multivariate analyses assessing association between the types of maltreatment and risk behavioral outcomes: based on expanded hierarchical type (EHT)

| No maltreatment | Neglect only | Physical abuse only | Sexual abuse only | Physical abuse plus neglect | Sexual abuse plus other maltreatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 3,667 51.6% |

n = 1,512 21.2% |

n = 718 9.9% |

n = 47 0.5% |

n = 957 13.0% |

n = 302 3.8% |

|

| Sexual Risk Behaviors | ||||||

| STD diagnosis | 1 | 1.4 (1.2–1.7)** | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)* | 2.9 (1.5–5.9)** | 1.9 (1.5–2.3)*** | 2.4 (1.8–3.3)*** |

| Sexual regret after alcohol use | 1 | 1.4 (1.2–1.7)** | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)*** | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 1.6 (1.3–2.0)*** | 2.1 (1.5–2.9)*** |

| Multiple sex partners | 1 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5)*** | 1.7 (1.4–2.1)*** | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8)*** | 2.2 (1.7–2.8)*** |

| Sex for money | 1 | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 1.0 (0.1–7.7) | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)** | 3.4 (2.0–6.0)*** |

| Sex before age 15 | 1 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6)*** | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)** | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 1.6 (1.3–1.9)*** | 2.2 (1.7–3.0)*** |

| Delinquency | ||||||

| Property damage | 1 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 2.1 (1.4–3.1)*** | 2.3 (0.7–7.8) | 2.4 (1.8–3.4)*** | 3.0 (1.9–4.6)*** |

| Selling drugs | 1 | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8)** | 1.7 (0.4–7.2) | 2.0 (1.3–2.7)** | 2.5 (1.5–4.1)*** |

| Fighting | 1 | 2.2 (1.5–3.2)*** | 3.2 (2.0–4.9)*** | 1.2 (0.2–8.9) | 2.7 (1.8–4.1)*** | 3.5 (2.1–6.0)*** |

| Gang affiliation | 1 | 1.2 (1.1–1.5)* | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.6)*** |

| Owning gun | 1 | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.5 (0.1–3.6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 2.6 (1.7–4.0)*** |

| Ever runaway | 1 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)** | 1.8 (1.4–2.5)*** | 0.5 (0.1–2.2) | 2.8 (2.3–3.5)*** | 3.6 (2.7–4.9)*** |

| Suicidality | ||||||

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6)*** | 0.5 (0.1–3.4) | 2.4 (1.9–3.2)*** | 4.3 (3.0–6.1)*** |

| Suicidal attempt | 1 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0 | 2.0 (1.2–3.1)** | 3.1 (1.7–5.5)*** |

Analysis controlled for race, age, education level, and depressive symptoms. (95% CI)

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that child maltreatment is a very common form of violence perpetrated by caregivers and that child maltreatment has sustainable negative effects on a wide range of developmental outcomes for women transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood. Specifically we incorporated the cumulative classification approach and the hierarchical classification approach using nationally representative data on risk behaviors among young women. Two principal findings are discussed in detail below.

Application of the Cumulative Classification Approach

Using the cumulative classification approach, subsequent risk behaviors increased monotonically with the number of types of maltreatment that the individual experienced. We found these robust and generally consistent patterns in terms of the numbers of types of maltreatment in all three domains of risk behaviors. These findings suggest that experiencing a larger number of different types of maltreatment during childhood leads to an extensive range of risk behaviors, which include internalizations, self-harm behaviors, externalizations, and depressive symptoms, over and above the effects of race, age, and education level. It also suggests that exposure to broader and more varied child maltreatment experiences has a greater and more pervasive impact on later outcomes. Other studies also have found cumulative effects of child maltreatment on a variety of outcomes. Finkelhor and his colleagues found that children with seven or more types of victimization (poly-victims) had significantly higher trauma scores than children who had experienced fewer types of victimization (Finkelhor and Browne 1985). Others also found that a higher number of types of adverse childhood experiences was associated with higher odds of sexual risk behaviors, including perceiving oneself as at risk of AIDS, having more sexual partners, and initiating sexual experiences at an early age (Hillis et al. 2001). Thus, our results are consistent with the existing literature supporting a cumulative approach.

We conducted a further analysis to test the cumulative effects within the group of women who reported maltreatment (not shown in tables). Specifically, we categorized participants as single-type vs. multi-type maltreatment (two types or three types); those who had no maltreatment history were excluded in the bivariate analysis. The overall patterns of this analysis also supported the cumulative effect hypothesis. It appears that those in the multi-type maltreatment group were more likely to exhibit greater problems related to self destructive behaviors and more severe forms of sexual risk behaviors than the single-type maltreatment group. Specifically, women in the multi-type maltreatment group with two or three maltreatment types were significantly different from women with only one maltreatment type in the following behaviors: compared to those with a single type of maltreatment, they were more likely to report suicidal ideation (p = 0.001) and attempted suicide (p = 0.003), more likely to report running away from home (p = 0.0001), more likely to report an STD diagnosis (p = 0.009), more likely to have had sex for money (p = 0.001), and more likely to have had sex before age 15 (p = 0.004). Similar results were observed when we controlled for race, age, education, and depressive symptoms. However, for the behaviors related to delinquency and less severe sexual risk behavior outcomes (property damage, selling drugs, fighting, gang affiliation, owning a gun, regretting having sex after drinking), there was no signifi-cant difference in the proportion of those behaviors between the single-type and multiple-type maltreatment groups.

Our findings from both the cumulative effects hypothesis testing as well as the follow up analysis suggest that when multiple stressors are combined and accumulated, those stressors have a cumulative impact on the expression of various risk behaviors among young women in general. Individuals who experienced multiple types of child maltreatment appear to be at greater risk for more severe forms of self-harm behavioral outcomes compared to those with a single-type maltreatment history. This result is similar to Arata and colleagues' study which found that those who had experienced multiple types of maltreatment, compared with those who had not experienced any maltreatment had greater symptoms of psychopathology (Arata et al. 2005). However, when the individuals who had experienced multiple types were compared with those who had experienced a single type, there was no significant difference in their delinquency outcomes.

Our findings also have important implications for research on child maltreatment. Previous studies often overlooked identifying if particular individuals within the maltreated group based on the numbers of maltreatment exposure may be at greater risk for specific behaviors (Finkelhor and Browne 1985). Testing the cumulative effect approach should include between group comparisons (i.e. no maltreatment vs. multiple-type maltreatment groups) as well as within maltreatment group comparisons (i.e. single-type maltreatment vs. multiple-type maltreatment). In sum, performing both types of comparisons will help researchers to understand more comprehensively the cumulative effect of maltreatment on several specific outcomes.

Application of the Expanded Hierarchical Type (EHT) Approach

Testing the EHT system with our data provides robust evidence that the combination of sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types is associated with the poorest outcomes. This combination had the largest odds ratios in 12 out of 13 risk behavior outcomes followed by physical abuse plus neglect, physical abuse only, neglect only, and sexual abuse only. The independent effect of sexual abuse only was significantly associated with an increased risk of STDs, but not with any other outcomes. It should be noted that the lack of significant associations in the sexual abuse only category may in part be explained by the small size of this subgroup (n = 47). Depending on the outcome and other assumptions, we estimate that hypothesis tests involving this subgroup would offer 80% power to detect odds ratios outside the range of 0.4–2.5 for infrequent outcomes (less than 5% prevalence in the whole sample, e.g., suicidal attempt, sex for money), or 0.7 to 1.4 for more common outcomes (e.g., STD diagnosis, multiple sex partners, gang affiliation, ever run away). Since many of the observed odds ratios within this subgroup in fact are within these ranges, our sample is likely underpowered to evaluate the risk of several outcomes within this particular subgroup.

Our study's results suggest that sexual abuse during childhood, when combined with physical abuse or neglect, leads to significant, long term, and pervasive effects on a wide range of maladaptive behaviors across the risk domains during adulthood. This result is particularly notable because many studies have examined the association between sexual abuse and sexually-related outcomes, while ignoring other domains such as delinquency or suicidality (Arriola et al. 2005; Paolucci et al. 2001; Senn et al. 2008). The current study provides a more complex consideration of the relationship between maltreatment categories and behavioral outcome categories.

The finding that sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types, and physical abuse plus neglect, had poorer outcomes compared to the other categories is similar to Lau and colleagues' finding (Lau et al. 2005). Although Bagley and Mallick used small samples of children, they also found that the combination of sexual abuse with another maltreatment type (either physical plus sexual abuse, or sexual plus emotional abuse) created a higher risk for both conduct and emotional disorders compared to other combinations, which included physical and emotional abuse or experiencing a single type of maltreatment (Bagley and Mallick 2000). Another notable finding is that neglect only was significantly associated with 7 out of 13 risk outcomes. This result indicates that the impact of neglect only is not much less than the impact of physical abuse only which was significantly associated with 9 out of 13 outcomes. As documented in Behl et al. (2003), the field is suffering from “neglect of neglect” (Kendall-Tackett and Eckenrode 1996), in which neglect has been less frequently included than other types of maltreatment in the child abuse literature in the past 22 years (1977–1998) (Behl et al. 2003). Researchers are urged to break this pattern of “neglect of neglect” and to focus future studies on investigating the extent to which neglect impacts risk outcomes in order to gain a full understanding of its role. In sum, our study's results provide validation for Lau's findings that sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types is associated with the majority of maladaptive developmental outcomes studied here, and offer the additional insight that different types of combinations of maltreatment are associated with different impacts on risk behavior profiles.

Limitations

When interpreting our results, several limitations of the Add Health data set should be recognized. First, Add Health includes retrospective reports of child maltreatment. It is possible that participants had under-reported their specific child maltreatment experiences due to recollection bias. In particular, we have observed that only 0.5% of our sample reported sexual abuse only and 3.8% reported sexual abuse and other maltreatment types, whereas physical abuse only was reported by almost 10%. It is possible that unconscious denial as well as concerns about societal disapproval might have operated in preventing recollection of severe cases of childhood abuse (Widom and Shepard 1996). Other studies have reported that compared to individuals with physical abuse, those with sexual abuse significantly under-reported their maltreatment experiences (Lewis et al. 1989). Thus, caution is needed to interpret the impact of sexual abuse maltreatment on risk behaviors.

Second, this study did not take into consideration the influence of maltreatment severity, timing, chronicity, or the actual frequencies of maltreatment. Third, the Add Health data only collected limited data on experiences of maltreatment (neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse), excluding other types of maltreatment such as peer/sibling abuse, verbal abuse, witnessing family violence, and emotional maltreatment. In particular, we were unable to create an emotional maltreatment only category that was originally included in Lau's EHT system due to a lack of data on emotional maltreatment. Future studies of women should test the impact of emotional maltreatment on the development of various risk behaviors, given growing evidence of a positive relationship between a history of emotional maltreatment and various risk behaviors (Teicher et al. 2006; Widom and Shepard 1996).

Conclusions

Despite the limitations above, our study has demonstrated that experiencing multiple forms of child maltreatment is a significant and serious public health problem because multiple forms of child maltreatment seem to be clearly and specifically linked to detrimental developmental sequelae.

Thus, our study has important ramifications for clinical practice, research, and public policy. Understanding the details of women's child maltreatment histories is an important first step for effective treatment of individuals with trauma. When clinicians assess histories, they should be cognizant of the need to determine a more specific maltreatment history: the specific types of maltreatment, whether or not multiple types were experienced, and whether or not sexual abuse co-occurred with other types of maltreatment. As Finkelhor (2007) indicates, the field should move beyond the preoccupation with sexual abuse only. In addition, clinicians should also assess a wide variety of client behavioral outcomes in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of child maltreatment on those outcomes. A detailed history of maltreatment can serve as a predictive tool for risk behaviors for clinicians who are working with young women. This information may also help clinicians to educate young women about developing appropriate coping strategies to replace risky behaviors associated with the trauma of childhood maltreatment.

In sum, our study provides a comprehensive picture of the role of co-occurring child maltreatment in a specifically targeted population by testing both the cumulative approach model and Lau's expanded hierarchical type (EHT) approach. Applying the EHT system in our study allowed us to overcome the cumulative classification's lack of consideration of possible differential effects of specific types or combinations of maltreatment. Therefore, the present study adds clarity in identifying the degree to which specific combinations and profiles of maltreatment influence risk behaviors among young women who are transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood. Our study also suggests that developing greater risk for harmful behaviors may not only be based purely on the exposure to cumulative effects of maltreatment but also on the specific profile of maltreatment. That is, a hierarchy exists within the types of maltreatment, and those who have experienced types of maltreatment that are higher on the hierarchy experience worse effects. Therefore, it may no longer be appropriate to assume that all types of maltreatment are equivalent in their potential contribution to developmental sequelae. Future studies should replicate these findings with other populations, including clinical samples and males, in order to inform specific and detailed policy recommendations for vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant 1K01 MH 086366-01A1, Mentored Research Scientist Developmental Grant, from the National Institute of Mental Health. Authors would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Anne Porter and Dr. Maryann Amodeo for their valuable comments and suggestions for this paper. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should refer to www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth/contract.html or contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 West Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27516-2524.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Hyeouk Chris Hahm is an Assistant Professor at Boston University School of Social Work. She received her PhD in Social Work from Columbia University and completed her post-doctoral fellowship at University of California, Berkeley, School of Social Welfare. Her fields of special interest include HIV/STDs risk factors, substance use/abuse, acculturation, health disparities, health care utilization patterns among ethnic minority adolescents and young adults.

Yoona Lee is a PhD graduate student in the department of psychology at Brandeis University. She received her master degrees in psychology from Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, and from Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. Her major research interests include child maltreatment, peer violence, bullying, victimization, and aggressive victimization, children and adolescent psychosocial, behavioral, and cognitive adjustment, and cross cultural research.

Al Ozonoff is an Associate Professor of Biostatistics at the Boston University School of Public Health. He received his PhD in Mathematics from the University of California, Santa Barbara. His major research interests include time series analysis and statistical methods for infectious disease epidemiology and public health surveillance.

Michael Van Wert is a second year MSW student at Boston University School of Social Work. His major research interests include trauma and interpersonal abuse.

References

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, Farrill-Swails OL. Single versus multi-type maltreatment. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma. 2005;11(4):29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arriola KR, Louden T, Doldren MA, Fortenberry RM. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29(6):725–746. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley C, Mallick K. Prediction of sexual, emotional, and physical maltreatment and mental health outcomes in a longitudinal cohort of 290 adolescent women. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(3):218–226. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research and design. Carolina Population Center. 1997 Retrieved January 10, 2009 from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html. [Google Scholar]

- Behl LE, Conyngham HA, May PF. Trends in child maltreatment literature. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Terranova AM. Effects of multiple maltreatment experiences among psychiatrically hospitalized youth. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32(6):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: AIDS weekly surveillance report, 1986. 1986

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: HIV/AIDS among women. 2007

- Chaudron LH, Caine ED. Suicide among women: A critical review. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 2004;59(2):125–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen AH, Crittenden PM. Physical and psychological maltreatment: Relations among types of maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect: The International Journal. 1991;15(2):5–18. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, DiLillo D, Martinez IG, DeGue S, Jeffcott M. Co-occurring forms of child maltreatment and adult adjustment reported by Latina college students. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27(7):751–767. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(2):172. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Mercy JA, Simon TR, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(6):474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePanfilis D, Zuravin SJ. Assessing risk to determine the need for services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(1):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Simantov E, Rickert VI. Effect of abuse on health results of a national survey. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(8):811–817. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28(7):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry. 1985;55(4):530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Herrenkohl RC. Examining the overlap and prediction of multiple forms of child maltreatment, stressors, and socioeconomic status: A longitudinal analysis of youth outcomes. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22(7):553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6(6):547–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;106(1):206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. Wiley-Interscience; New Jersey: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jun HJ, Rich-Edwards JW, Boynton-Jarrett R, Wright RJ. Intimate partner violence and cigarette smoking: Association between smoking risk and psychological abuse with and without co-occurrence of physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(3):527–535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett KA, Eckenrode J. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: A developmental perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):339–351. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):233–245. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Leeb RT, English D, Graham JC, Briggs EC, Brody KE, et al. What's in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29(5):533–551. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DO, Mallouch C, Webb V. Child abuse, delinquency, and violent criminality. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and violent delinquency: Disentangling main effects and subgroup effects. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):246–258. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, Handcock MS, Schmitz JL, Hobbs MM, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. Jama. 2004;291(18):2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki EK. Gender differences in completed and attempted suicides. Annals of Epidemiology. 1994;4(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. Journal of Psychology. 2001;135(1):17–36. doi: 10.1080/00223980109603677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrak J, Byrne A, Baker M. The association between abuse in childhood and STD/HIV risk behaviours in female genitourinary (GU) clinic attendees. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2000;76(6):457–461. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.6.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. American Psychiatric Association. 1992;149:999–1010. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1(3):385. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Jama. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Janal M. Gender in suicide attempt rates and childhood sexual abuse rates: Is there an interaction? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36(3):329–335. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger S, Rosario M, Feldman RS. Physical child abuse and adolescent violent delinquency: the mediating and moderating roles of personal relationships. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):208–219. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JM, Tesadale JD, Gemar M. A cognitive science perspective on kindling and episode sensitization in recurrent affective disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26(2):371. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(5):711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Edwards EM, Heeren T. Child abuse and neglect: relations to adolescent binge drinking in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) study. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(3):277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: Juvenile arrests 1996. Bulletin. 1997

- Snyder HN. Juvenile arrests 2006. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson MW, Fischer KW, Burdzovic Andreas J, Smith KW. Pathways to aggression in children and adolescents. Harvard Educational Review. 2004;74(4):404–430. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Shepard RL. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part I. Childhood physical abuse. Psychological assessment. 1996;8:412–421. [Google Scholar]