Abstract

Background

In human basophils from different subjects, maximum IgE-mediated histamine release and the level of syk protein expression correlate well. Recent studies suggest that in some patients treated with omalizumab, the response to stimulation with anti-IgE antibody increases. In unrelated studies, there is also evidence that the composition of FcεRI in basophils differs among subjects. This observation raised the possibility that the stoichiometry of FcRβ:FcεRIα is not fixed to 1:1 and might be modifiable during changes in the basophil environment.

Objective

To determine if treatment with omalizumab results in increases in syk expression, anti-IgE-mediated histamine release and disproportionately alters the relative presence of FcRβ and FcεRIα.

Method

Syk, FcεRIα, and FcRβ expression was monitored during the treatment of subjects with omalizumab.

Results

Treatment with omalizumab reduced histamine release from peripheral blood leukocytes stimulated with cat-allergen in vitro, but histamine release stimulated with anti-IgE antibody increased 2 fold. Expression of syk increased 1.86 fold. There was no change in the expression of c-cbl, a signaling element that is sensitive to the presence of IL-3, and no increase in response to FMLP, a response that also increases in the presence of IL-3. There was a 60% decrease in the FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio in patients treated with omalizumab.

Conclusions

In the context of previous studies, these studies provide support for a proposal that syk expression is modulated in vivo by an IgE-dependent mechanism and that the ratio of FcεRI alpha and beta subunits in basophils is influenced by factors extrinsic to the cell.

Keywords: omalizumab

Introduction

Omalizumab is a therapeutic anti-IgE antibody that has the ability to regulate expression of atopy by preventing the binding of IgE to both high and low affinity IgE receptors without directly inducing aggregation of previously cell bound IgE. Previous studies have shown that treatment results in reductions in cell surface IgE of 90–99%1, 2. Because the high affinity IgE receptor is also regulated by the presence of bound IgE, a reduction in the solution phase free IgE shifts the steady state balance of cellular synthesis and loss of FcεRI on the cell surface3. The absence of bound IgE favors the loss mechanism resulting in a marked reduction in the cell surface expression of FcεRI. Reductions in free IgE need to be marked because basophils and mast cells respond well with less than 1000 antigen-specific IgE molecules per cell4, 5 and the mean total surface IgE (all antigen specificities) is nearly one-quarter million per cell prior to treatment. If reductions are sufficient, the expectation and functional consequence is that induction of IgE-mediated secretion from mast cells and basophils will be blunted. In vitro studies of basophils obtained from treated patients do indeed demonstrate marked blunting of antigen-induced histamine release1. However, in a recent study of patients with chronic urticaria being treated with omalizumab, it was noted that histamine release from peripheral blood basophils stimulated with anti-IgE antibody increased during treatment even though cell surface IgE was reduced6. This was an unexpected result that may have its origins in the nature of chronic urticaria. But, based on recent studies of signaling in basophils, there were other possible explanations.

IgE-mediated secretion from human basophils is dependent on a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic influences. A number of signal transduction elements have been demonstrated to be necessary for secretion but recent studies have suggested that the natural biological variation in IgE-mediated histamine release from basophils in the general population is only concordant with variation in expression of the early tyrosine kinase syk5, 7–9. The expression levels of this non-redundant receptor-associated kinase appear to be rate-limiting5. Typical human basophils express 100,000–500,000 IgE receptors (the high end found predominately in atopic subjects), but only express 25,000 molecules of syk per cell5. In the context of IgE-mediated release initiated by the crosslinking pan-stimulus, anti-IgE antibody, these low levels of syk may limit full expression of the reaction. In contrast, if the reaction is initiated by specific antigens, it is not as apparent that syk will be rate-limiting because the specific-to-total IgE ratios in atopic patients average 1%10. Therefore, in an atopic patient with 250,000 receptors, only 2500 are occupied with an antigen-specific IgE and the ratio of relevant receptor:syk (1:10) is the reverse of the ratio observed during stimulation with anti-IgE Ab (10:1). But since a typical reaction is a balance between the rate of activation vs. the rate of de-activation, where de-activation occurs independently of syk11, even antigenic stimulation might benefit from greater levels of syk expression.

In human basophils, syk expression is known to be altered by three mechanisms. First, IgE-mediated secretion itself results in down-regulation12, 13. Second, some non-IgE-dependent receptors use syk as a signaling element and also induce modest down-regulation of syk14, 15. Even a non-IgE-dependent receptor, FMLP-R, which does not appear to use syk for signaling16, induces modest loss of syk14. Finally, IL-3 can increase syk expression although many other signaling elements are also up-regulated5, 7, 17, 18. The IgE-mediated process of syk loss is interesting because even low levels of receptor stimulation that do not initiate mediator release may induce loss of syk13. The process is slow13 but integrative5, 13. The close association between syk expression and anti-IgE-mediated histamine release suggested the hypothesis that increases in anti-IgE-mediated histamine during treatment with omalizumab may result from changes in the expression of syk.

Recent studies of basophils maturing from CD34+ progenitors have suggested another counter-intuitive hypothesis19. CD34+ progenitors expressed 11–12 fold more syk than peripheral blood basophils (PBB). When cultured for 3 weeks in IL-3, these cells matured into basophil-like cells that continued to express 11-12 fold more syk than PBB. However, when progenitors were cultured in the presence of a chronic FcεRI-aggregating stimulus, FcεRI expression, alcian blue staining and histamine content remained the same but syk expression was markedly reduced. These results suggested that if some form of chronic aggregation occurs in patients, then syk expression would be down-regulated. Relief of this chronic aggregation by elimination of IgE might reverse the induced down-regulation and result in a basophil that expressed higher levels of syk and was more responsive to a pan-stimulus like anti-IgE antibody. Treatment with omalizumab offered a means to test this prediction.

Treatment with omalizumab results in changes in the cell surface expression levels of FcεRI and previous studies have noted that the subunit stoichiometry, notably the relative amount of FcRβ, appears to differ among individuals expressing very different levels of FcεRI. In humans, the receptor can be expressed on the cell surface in two forms, a heterotrimer, αγ2, or a heterotetramer, αβγ2. There are indications that in basophils (similar data for the mast cell has not been generated although there is indirect evidence that the relative presence of FcRβ might not be constant20), there is probably a mixture of αγ2 and αβγ2. In the one study where the relative presence of the beta subunit (FcRβ) has been examined, the ratio of FcRβ:FcεRIα is correlated with the absolute level of cell surface expression of FcεRI, i.e., a relative increase in beta appears to increase surface FcεRI21. Based on this prior study, one might predict that omalizumab treatment might reduce the relative expression of FcRβ. Because this subunit may contribute to signaling strength22, such changes might oppose increases in basophil responsiveness. Therefore, at a minimum, relative FcRβ expression needed to be monitored as a potential confounding variable. However, the apparent linkage between the expression of FcRβ and expression of cell surface FcεRI does not necessarily imply that the relative amount of FcRβ is a variable that can be manipulated by treatment. Rather, the ratio of beta:alpha may be an intrinsic characteristic of an individual's basophil genotype and it is unaltered by conditions extrinsic to the basophil. Treatment with omalizumab also offered a way to explore this question. Therefore, in conjunction with the assessment of syk, basophils were examined for changes in the FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Buffers

The online repository provides a detailed description of reagents and buffers. These have been described in previous publications5.

Analysis of syk protein expression by intracellular flow cytometry

All analysis was performed on a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. The measurement of syk protein expression by flow cytometry using the anti-syk antibody 4D10 has been previously described and validated with respect to standard Western blotting9, 14. This method has been used on both impure as well as purified cell fractions with equivalent results. Briefly, fixed mixed leukocytes were labeled with anti-IL-3R and anti-BDCA2 antibodies (phycoerythin and FITC, respectively) and permeabilized (Fix and Perm Kit, Caltag, Carlsbad, CA) in the presence of 4D10 or IgG2a antibody. Cells were then incubated with an anti-mIgG2a –alexa647 antibody to complete the labeling. Syk protein expression is reported as normalized net MFI, the difference between 4D10 and isotype-labeled cells corrected for instrument variability using CaliBRITE APC calibration beads (BD Biosciences).

Flow cytometry was performed to detect FcεRIα and IgE on the cell surface using anti-FcεRIα antibody, 22E7 (which detects occupied and unoccupied FcεRIα) and goat anti-IgE Ab as previously described23 (see the online repository)).

Omalizumab study24

The details of this study have been recently published24 and further details can be found in the online repository. Briefly, adults, 18–50 years old, were chosen for their sensitivity to cat allergen. Informed consent was obtained via a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' Data Safety Monitoring Boards. After testing for inclusion criteria, adults were entered into the study after a 2 week interval and randomized 3.5:1 omalizumab to placebo treatment. On the first day of treatment (BSL), prior to the first injection of either placebo or omalizumab (according to the manufacturer's dosage schedule), venipuncture and a nasal challenge were performed. The blood was processed by separation on single (throughout study period) or double Percoll gradients (only pre-treatment and final visits). The cells from the 1-step Percoll gradient were analyzed by flow cytometry for cell surface levels of FcεRIα and IgE, internal levels of syk, or used to assess histamine release in response to stimulation with anti-IgE antibody, cat allergen extract, or FMLP. After entry, subjects were tested for basophil receptor and IgE expression and histamine release on days 3, 11, 17, 23, 30, 36, 44 and 10424. If the cat allergen response decreased below 20% of the basophil response prior to entry or the day 45 time point was reached first, further testing was stopped until the 14 week assessment. At this mid point (MID) in treatment, the subject was tested again for the study's various endpoints. The visit 14 (ca. 104 days) assessment is considered the FINAL measurement. At the BSL and FINAL visits, basophils were purified for Western blotting to measure FcεRI alpha and beta, c-cbl, and syk. In a subset of patients, flow cytometric syk measurements were made on a weekly basis.

Western blot analysis

At BSL and FINAL visits, basophils were purified by a combination of two-step Percoll gradient and negative selection using a basophil cocktail from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, BC) (basophil purification kit) and columns from Miltenyi (Aubum, CA)5. The purity of basophils was determined by alcian blue staining25 and basophils purified generally exceeded 97% purity. Relative to pre-purification counts, recovery of purified basophils was >85%. Basophils were lysed in 1X ESB buffer at a density of 300,000/20 μl of ESB, boiled for 5 minutes and stored at −70°C until SDS-PAGE analysis. Samples for individual subjects were stored until both visit 2 and visit 14 (see below) could be analyzed together. Western blotting, pretreatment (BSL) and 104 days (FINAL) samples, for several proteins, including c-cbl was performed in a semi-quantitative manner with calibration standards as described previously5. Briefly, 4 dilutions (1.0, 0.4, 0.15 and 0.05, where 1.0 = undiluted lysate) of a standard preparation of basophils were run with samples in 15-lane 10% gels, with molecular weight markers in the first and last lanes (see the online respository, Figure E4). After transfer to nitrocellulose, the nitrocellulose was cut at the 40 kD and 90 kD horizontal position and the <40 portion blotted for FcRβ, the >40 kD, <90 kD portion blotted for FcεRIα and the >90 kD portion blotted for c-Cbl. After blotting with 22E7, The >40 kD, <90kD segment was also blotted with anti-syk (4D10) antibody. For the in vitro studies or receptor expression, lane loading was also checked by blotting with anti-p85 antibody (p85 subunit of PI3 kinase) which we have previously found not to change during culture with IL-3)5.

Results

Omalizumab study: Histamine Release, Syk and FcRβ Expression

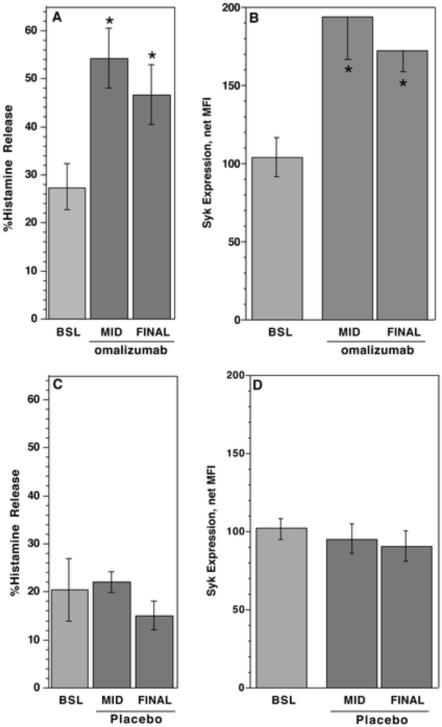

In the omalizumab treated subjects, cell surface IgE on basophils decreased to 0.05 ± 0.02 fold of its starting level by the FINAL visit (ca. 104 days). There was no change (1.11 ± 0.24 fold of starting levels) in patients treated with placebo agent. Figure E1, in the online repository shows the kinetics of the changes in cell surface FcεRI and IgE on basophils during treatment. At the final visit, day 104, histamine release induced by optimal concentrations of cat antigen decreased to 0.15 ± 0.12 fold of pre-treatment responses24. In contrast, histamine release induced by anti-IgE antibody increased (Figure 1A) (p=0.004, n=12) in subjects treated with omalizumab and did not change in the placebo group (p=n.s., n=4) (Figure 1C). Concordant with the increase in histamine release induced by anti-IgE antibody was an increase in syk expression in basophils from subjects treated with omalizumab increased (Figure 1B). It did not increase in basophils from subjects treated with placebo agent (Figure 1D). There was a correlation between the fold increase in syk expression and the fold increase in anti-IgE Ab-induced histamine release of 0.73 (p=0.014).

Figure 1. Increases in syk expression and anti-IgE mediated histamine release in subjects treated with omalizumab.

(A) Measurement of histamine release induced with an optimal concentration of anti-IgE antibody on pre-treatment (Day 0, BSL), 4–6 weeks after the start of treatment (MID), and 15 weeks (ca. 104 days) after the start of treatment (FINAL) for subjects treated with omalizumab (n=12). (B) Measurement of syk expression in basophils by flow cytometry for the same group of subjects in panel A. (C) Measurement of histamine release induced with anti-IgE antibody in the placebo group (n=4). (D) Measurement of syk expression by flow cytometry in the placebo group. Spontaneous histamine release averaged 3 ± 0.3%. It was not different between groups and did not change during the course of the study.

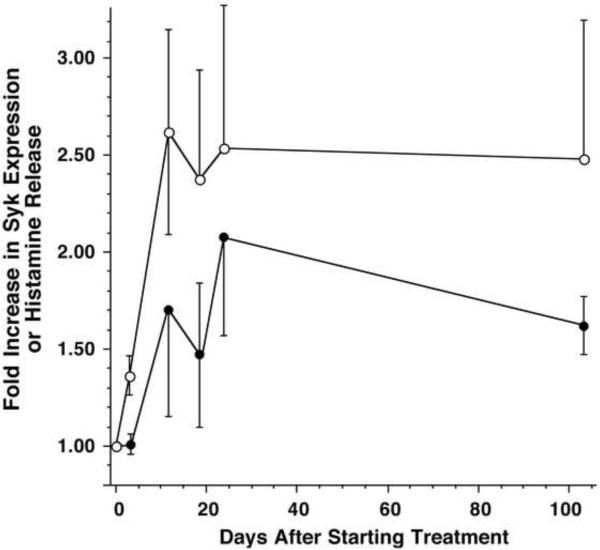

In 6 subjects, the kinetics of the increase in syk expression was measured weekly (Figure 2). For the same subjects, Figure 2 shows the time course for the increase in histamine release induced by anti-IgE Ab. The increase in histamine release and syk expression occurred early in treatment, with the peak increase apparent by 2–3 weeks. A similar kinetics for histamine release held for all 12 subjects treated with omalizumab (data not shown).

Figure 2. Kinetics of the increase in anti-IgE Ab-induced histamine release and syk expression.

The data is expressed relative to the pre-treatment response or levels of syk expression (n=6); (◯) histamine release induced by anti-IgE antibody and (●) syk expression measured by flow cytometry. Both kinetic curves, taken as a whole, are statistically different than no change (1.0)(p<0.0001).

As we have observed previously, plasmacytoid dendritic cells – a leukocyte that also expresses FcεRI -- display 30-fold greater syk expression than peripheral blood basophil19. Figure E2 (online repository) shows that pDC expression of syk did not change in either the treated or placebo groups.

Histamine content in basophils did not change (1.21 ± 0.16 vs. 1.28 ± 0.04 pg/basophil, pre-treatment vs. 104 days, respectively). The number of alcian blue positive cells in Percoll separated preparations did not change; 24,000±5,000 per ml of blood at pre-treatment and 26,000±5,000 per ml at visit 14 (15 weeks) for an average ratio of counts at the final visit (ca. 104 days) vs. pre-treatment in the omalizumab group of 1.23±0.13 (p = 0.106).

Our previous studies of syk expression in peripheral blood basophils have noted that expression ranges from near zero (MFI units) to 200–250 MFI units (with the mean at 110)9. Figure E3 in the online repository shows that there was a relationship between the fold up-regulation of syk in subjects on omalizumab relative to their starting syk levels. If syk were expressed at levels already considered the high end for the general population, then treatment with omalizumab did not increase expression further.

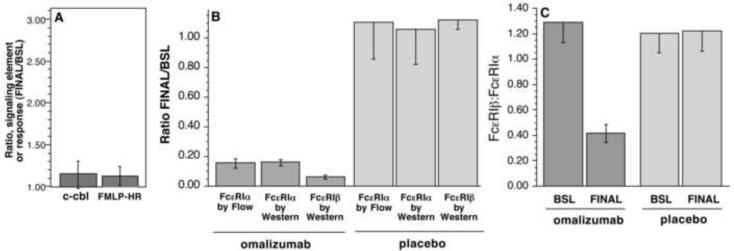

Previous studies have shown that in vitro culture of peripheral blood basophils with 10 ng/ml of IL-3 will alter signaling element expression patterns5. Therefore, the observed increase in syk expression in basophils during treatment with omalizumab might result from increases in IL-3. However, previous studies have also noted that IL-3 induces increased expression of several other signaling elements, including those associated with negative regulation of the signaling. If the syk increase resulted from an increased presence of IL-3 or a cytokine with similar functional effects (e.g., IL-5), then there should also be increases in c-cbl or FcRβ5, 21, 26. For example, previous studies have shown that in vitro, c-cbl, FcRβ, and the histamine response to FMLP increased 2.7, 3.0 and 2.1 fold, respectively, in the presence of IL-35, 21, 26, 27. However, no change in basophil c-cbl expression was observed in the omalizumab treatment group (and no change was observed in the placebo group) (Figure 3, panel A). In addition, there was no change in the basophil response to FMLP stimulation (Figure 3, panel A).

Figure 3. Effect of omalizumab treatment on other IL-3 sensitive characteristics of human basophils.

(A) The ratio of the measured expression of c-cbl in purified basophils (as assessed by quantitative Western blots) or the ratio of percent histamine release induced by 1 μM FMLP. The ratio is calculated as the endpoint at day 104 (FINAL) divided by the endpoint pre-treatment (day 0, BSL). (B) Expression of cell surface FcεRIα and bound IgE levels on peripheral blood basophils from omalizumab treated or placebo subjects were determined by flow cytometry and by Western blotting. The ratio of expression level at day 104 (FINAL) to pre-treatment (BSL) is plotted (n=12, treated with omalizumab, n=4, treated with placebo agent). (C) The ratio of expression of FcRβ and FcεRIα as determined by Western blot analysis of purified blood basophils from omalizumab treated or placebo subjects (BSL and FINAL). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

In vitro incubation of basophils with IL-3 has also been noted to increase the expression of the beta subunit (FcRβ) of FcεRI21, 26. In our previous study of FcRβ and FcεRIα expression in human basophils, the expression levels were determined by lysing cells and analyzing total p60 FcεRIα or FcRβ by Western blotting21. This same methodology was employed in the current study but the method was improved by including a 4-point dilution series of a basophil standard within each Western blot. This was necessary since the Western blot was non-linear throughout the possible range of receptor expression found at different points of the omalizumab study. Figure E4 in the online respository shows one example Western blot of samples made before and after treatment with omalizumab. Figure 3, panels B & C, summarizes the results for changes in both the broad p60 FcεRIα band (which represents cell surface receptor) and the FcRβ band. The decrease in p60 by Western is similar to the decrease in surface FcεRI as detected by flow cytometry. Expression of p60 at the FINAL visit (ca. 104 days) decreased to 17±2% of pre-treatment levels whether analyzed by flow cytometry or by densitometric analysis of the semi-quantitative Western blot of p60 (p<0.0001 when compared to pre-treatment baseline (BSL), p = n.s. when comparing flow and Western methodologies for measurement of FcεRIα). The levels were unchanged in the placebo (4 subjects) group. In contrast, after the FINAL treatment visit the expression of FcRβ decreased to 8±3% of the levels observed prior to treatment (p = 0.0025 when comparing the change in FcRβ and FcεRIα by Western blotting). Again, there was no change observed in the placebo-treatment group. When the data was expressed as a ratio of FcRβ:FcεRIα(p60), the ratio at the FINAL treatment visit decreased to 0.43 fold the ratio observed prior to treatment (p=0.0004 | Ho = 1.0). There was no change in the ratio in the placebo-treatment group. Using the same nitrocellulose blots and blotting for syk expression, the ratio of FINAL/BSL for the omalizumab group was 1.55±0.19, p = 0.013 (Ho | ratio = 1.0), recapitulating the results obtained by flow cytometry. There were two collateral observations that were worth noting, the heterogeneity of glycosylation of the p60 cell surface FcεRIα was found to decrease following treatment and there was a modest increase in the presence of the internal immature FcεRIα, p46 (see online respository).

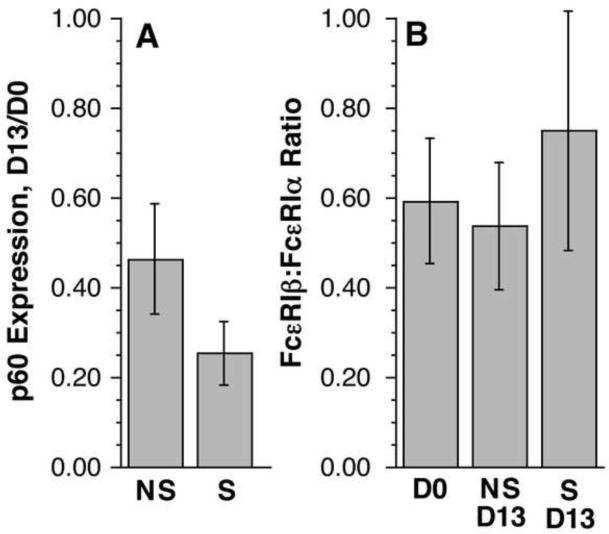

In vitro induced changes in FcRβ:FcεRIα

The change in relative FcRβ expression in patients treated with omalizumb raised a question of whether the change would occur whenever receptor down-regulation occurred in the absence of free IgE. Purified peripheral blood basophils were cultured for 13 days in the absence of IgE in order to induce down-regulation of FcεRI. To accelerate the process of receptor loss, a portion of the cells were first briefly treated with mild lactic acid buffer to gently dissociate endogenous IgE. To enhance survival of the basophils for 13 days, the cultures contained 10 ng/ml IL-3. Lysates on day 0 and day 13 were run in the semi-quantitative Western blot to also assess relative changes in FcRβ:FcεRIα ratios. For these experiments, the change in receptor expression is not as marked as obtained in the omalizumab study but Figure 4, panel A shows the decrease in receptor expression was statistically significant for both “non-stripped” and the “stripped” cells. The non-stripped cells did experience the expected 50% average decrease in FcεRI expression found in previous studies28. There was no change in the FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio for either group of cells (Figure 4, panel B). These results suggest that simply down-regulating receptor, in the presence of IL-3, is not sufficient to alter the FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio.

Figure 4. Absence of change in FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio in vitro.

Purified basophils were cultured in RPMI-1640 with IL-3 (10 ng/ml) for 13 days (D13) either without (NS) or with (S) prior lactic acid treatment to remove endogenously bound IgE. After 13 days of culture, cells were counted, lysed, and lysates analyzed by the semi-quantitative Western blot procedure used in the omalizumab study in order to quantitatively assess expression levels. (A) Expression of p60, relative to pre-culture levels (D0) for non-stripped and stripped cells (n=5) (p = 0.12 | Ho = 1.0 for non-stripped (NS) cells and p= 0.0005 | Ho = 1.0 for stripped (S) cells). (B) Ratio of FcRβ:FcεRIα for Day 0 (D0) and non-stripped (NS) and stripped cells (S) on day 13 (D13) (n=5) (p = n.s. for comparison of 3 groups). Errors shown represent SEM.

Discussion

Treatment with omalizumab results in a relatively rapid increased expression of syk in peripheral blood basophils that is concordant with an increase in histamine release induced by anti-IgE antibody. As noted above, incubation of peripheral blood basophils with IL-3 is the only known mechanism by which syk expression is induced to increase. Culture in IL-3 and IL-5 have also been shown to alter a variety of other signaling elements and to generally enhance the response of basophils to a wide variety of stimuli5, 21, 26, 27. IL-3 induces an increase in c-cbl expression that is 6 fold greater than the induction of syk expression. IL-3 has also been shown to markedly enhance mediator release induced by the G-protein-linked receptor for FMLP. Treatment with omalizumab caused neither an increase in c-cbl expression or responsiveness to FMLP. These results were therefore not consistent with the increase in syk expression resulting from exposure of basophils to cytokines like IL-3. In addition, treatment with omalizumab not only did not increase the relative expression of FcRβ, expression was suppressed relative to the expected decrease in FcεRI. This result suggests that treatment with omalizumab actually results in a suppression of a cytokine environment that promotes balanced expression of FcRβ and FcεRIα. Previous studies of omalizumab treatment have also indirectly suggested that the presence of Th2-associated cytokines (e.g., IL-3, IL-5) may decrease because the number of tissue T cells is found to decrease29–32. Whether this change is reflected globally has yet to be shown.

The secondary goal of this study was to determine if the FcRβ:FcεRIα ratio in peripheral blood basophils was a constant feature (an intrinsic characteristic) of an individual's FcεRI expression or whether it could be induced to change by altering the environment of the basophil. The ability to reduce free circulating IgE levels with omalizumab offered a way to 1) induce a reduction in basophil FcεRI and/or 2) potentially alter the atopic environment of the patient by changing the presence of Th-2-like cytokines or by other mechanisms not yet defined. The study showed that there was a disproportionate decrease in the expression of FcRβ relative to the decrease in total FcεRIα. This result leads to the conclusion that the relative presence of FcRβ is sensitive to factors extrinsic to the basophil.

This study can not directly address whether the changes in FcRβ:FcεRIα reflect a change in the stoichiometry of cell surface receptor. Underlying the ambiguity is the possibility that there is some FcRβ inside the cell or associated with other receptors (for convenience, both possibilities will be covered under the single term “internal”, but as noted in the repository, expression levels associated with other receptors would not be expected to change) and the Western blotting method does not discriminate “internal” vs. surface subunit expression (unlike the case for FcεRIα). In addition, the relative efficiency of the two antibodies used to detect FcεRIα and FcRβ is unknown. However, there are two closely related lines of reasoning, presented in the online repository (Figure E5), that suggest that the ratio may reflect differences in surface receptor stoichiometry. In other words, not only is total FcRβ disproportionally suppressed but it seems likely that surface stoichiometry is suppressed during treatment with omalizumab.

If the increase in syk expression was not consistent with the other properties of exposure of basophils to cytokines like IL-3, an increase in syk could result from a relief from a down-regulatory mechanism like that follows aggregation. As noted in the introduction, a recent study from our group has shown that chronic exposure of basophils developing from CD34+ progenitors to an aggregating stimulus results in cells that express normal levels of histamine, granularity and surface FceRI but reduced expression of syk19. In the current study, treatment with omalizumab did not alter histamine content or the number of alcian blue positive cells, a result consistent with the predictions of the in vitro studies19. However, omalizumab reduces free IgE levels sufficiently to markedly down-regulate FcεRI and especially cell surface IgE1, 33, 34. We could speculate that these conditions may be sufficient to relieve a chronic ongoing IgE-dependent aggregation of maturing basophils, if this occurs in vivo, and result in an increase in syk without other changes in the basophil phenotype. The increase occurred relatively quickly; an increase was evident within the first 2–3 weeks. Depending on the maturation time for basophils developing in the bone marrow, some delay would be expected, perhaps as short as 3 days but a change likely within 1–2 weeks. This expectation is drawn from our studies of FcεRI changes1 and the understanding that the kinetics of the receptor changes reflect the maturation kinetics35. There is not yet direct evidence that reversal of a post-translational mechanism like ubiquinylation (a process that is described for syk loss in mature basophils13) is operative in this situation or whether syk changes result from pre-translational events such as up-regulation of mRNA levels.

There remain several issues with this explanation, however. Most notable is that low syk expression levels in basophils are found in both non-atopic and atopic subjects. There would be no a priori reason for non-atopic subject's basophils to experience chronic IgE-dependent aggregation. But this assumption may be false. It has been noted that both atopic and non-atopic sera contain various levels of anti-IgE and anti-FcεRIα antibodies6, 36. The functional relevance of these antibodies in a wide variety of subjects is not currently understood. One hypothesis is that having these auto-antibodies does result in a functional outcome that is not always to induce disease as proposed for some patients with chronic urticaria36 and that outcome is the down-regulation of syk in maturing basophils.

The increase in responsiveness to stimulation of basophils with anti-IgE antibody is different from our previous experience with omalizumab treatment1. During manuscript preparation another new published study of omalizumab treatment found no changes in the basophil response to anti-IgE antibody37. But in that study, the starting response was nearly as high as one can find in basophils (>75%), so there was little room to observe an increase. In a previous phase I trial of omalizumab, the response to anti-IgE antibody decreased approximately 50%1. However, we made note of important differences between the two studies; table 1 summarizes the differences in IgE densities between the two studies. The cause of the differences may be the mode of administration of omalizumab (IV vs. SC) and an average lower level of dosing under the current dosing table regimen relative to the dosing achieved in the phase I trial. Several previous studies have shown that basophils require approximately 2000 cell surface IgE molecules to achieve 50% of their maximal responsiveness4, 5. A density of 3000–5000 is sufficient for a maximal response. In the phase I trial, total cell surface IgE decreased to unmeasurable levels for many subjects. Based on the technique used at that time, an average upper limit of 2200 molecules could be calculated. Therefore, the finding that stimulation with anti-IgE antibody was suppressed by 50% was expected. In the current study, there are approximately 6800 total IgE molecules per basophil, a density sufficient for a maximal response. If the response is augmented by increased levels of syk expression, then anti-IgE becomes a useful tool to detect these increases provided suppression is not too great. The current study did observe a decrease in response to cat allergen. However, this might be expected since cat-specific IgE densities would be low. For example, the median ratio of cat-specific IgE to total IgE was 4.2% (somewhat higher than the expected 1% for the general cat-allergic population10), which would predict around 290 molecules of cat-specific IgE per basophil. This level is far below the density required to support a strong histamine release response. Although the increase in syk expression would be expected to mitigate the suppression caused by reduced receptor expression, the densities of cat-specific IgE were probably too low for the syk increase to markedly overcome the suppression produced by a decrease in the density of the relevant IgE. However, one might speculate that stimulation with multiple antigens might reach high enough levels where the increase in syk expression exerts enough influence to effectively blunt the efficacy of treatment with omalizumab. These results suggest another possible reason for treatment failure.

Table 1.

Comparison of Changes in IgE density on basophil following omalizumab treatment for the 1996 (phase 1 trial) and the current 2008 study.

| STUDY | IgE/basophil | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Fraction | |

| 1996 phase 1 | 240000 | <2200 | 0.009 |

| 2008(current) | 134000 | 6800 | 0.051 |

If in vitro studies are a guide22, the relative absence of FcRβ as a component of the cell surface receptor would reduce the efficacy of aggregates (on a per aggregate basis) to initiate the IgE-dependent signaling cascade that leads to mediator release and other functions. This change in FcRβ expression might have mitigated the effects of increased syk expression but the fact that histamine release was also enhanced suggests that there was little counterbalancing effect by the expression of less FcRβ.

Key Messages.

Treatment of cat allergic subjects with omalizumab results in increased expression of syk in circulating basophils. One interpretation is that chronic aggregation of FcεRI in vivo is relieved by the reduction in FcεRI expression that accompanies treatment.

Treatment with omalizumab results in changes to the basophil response that increase its intrinsic sensitivity to stimulation, a change that counter-balanced by large reduction in cell surface antigen-specific IgE.

Capsule Summary.

This study provided evidence supporting a prediction that treatment of atopic subjects with omalizumab would increase the expression of the critical FcεRI-associated kinase, syk.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Meghan Sterba and Valerie Alexander for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants AI20253 and AI070345 to DWM.

Abbreviations

- FMLP

Formyl-met-leu-phe (tripeptide)

- IL-3

interleukin-3

- PI3K

phosphatidyl inositol 3' kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.MacGlashan J, D. W, Bochner BS, Adelman DC, Jardieu PM, Togias A, Mckenzie-White J, et al. Down-regulation of FceRI expression on human basophils during in vivo treatment of atopic patients with anti-IgE antibody. J. Immunol. 1997;158:1438–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prussin C, Griffith DT, Boesel KM, Lin H, Foster B, Casale TB. Omalizumab treatment downregulates dendritic cell FcepsilonRI expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGlashan D, Jr., Xia HZ, Schwartz LB, Gong J. IgE-regulated loss, not IgE-regulated synthesis, controls expression of FcepsilonRI in human basophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:207–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacGlashan DW., Jr. Releasability of human basophils: Cellular sensitivity and maximal histamine release are independent variables. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:605–15. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90266-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacGlashan DW., Jr. Relationship Between Syk and SHIP Expression and Secretion from Human Basophils in the General Population. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;119:626–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckman JA, Hamilton RG, Gober LM, Sterba PM, Saini SS. Basophil Phenotypes in Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria in Relation to Disease Activity and Autoantibodies. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1956–63. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kepley CL, Youssef L, Andrews RP, Wilson BS, Oliver JM. Syk deficiency in nonreleaser basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavens-Phillips SE, MacGlashan DW., Jr. The tyrosine kinases, p53/56lyn and p72syk are differentially expressed at the protein level but not at the mRNA level in non-releasing human basophils. Amer. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000;23:566–71. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.4.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishmael S, MacGlashan DW., Jr. Early Signal Protein Expression Profiles in Basophils: A Population Study. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;86:313–25. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1208724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erwin EA, Ronmark E, Wickens K, Perzanowski MS, Barry D, Lundback B, et al. Contribution of dust mite and cat specific IgE to total IgE: relevance to asthma prevalence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacGlashan DW, Jr., Undem BJ. Inducing an Anergic State in Mast Cells and Basophils without Secretion. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;121:1500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepley CL. Antigen-induced reduction in mast cell and basophil functional responses due to reduced Syk protein levels. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;138:29–39. doi: 10.1159/000087355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacGlashan D, Miura K. Loss of syk kinase during IgE-mediated stimulation of human basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGlashan DW, Jr., Ishmael S, Macdonald SM, Langdon JM, Arm JP, Sloane DE. Induced Loss of Syk in Human Basophils by Non-IgE-Dependent Stimuli. J Immunol. 2008;180:4208–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youssef LA, Wilson BS, Oliver JM. Proteasome-dependent regulation of Syk tyrosine kinase levels in human basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:366–73. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.127562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura K, Lavens-Phillips SE, MacGlashan DW., Jr. Piceatannol is an effective inhibitor of IgE-mediated secretion from human basophils but is neither selective for this receptor nor acts on syk kinase at concentrations where mediator release inhibition occurs. Clin. Expt. Allergy. 2001;31:1732–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi M, Hirai K, Ohta K, Suzuki K, Kitani S, Takaishi T, et al. Nonreleasing basophils convert to releasing basophils by culturing with IL-3. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:1279–87. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kepley CL, Youssef L, Andrews RP, Wilson BS, Oliver JM. Multiple defects in Fc epsilon RI signaling in Syk-deficient nonreleaser basophils and IL-3-induced recovery of Syk expression and secretion. J Immunol. 2000;165:5913–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishmael S, MacGlashan DW., Jr. Syk Expression in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes, CD34+ Progenitors and CD34−derived Basophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509336. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuda A, Okayama Y, Ebihara N, Yokoi N, Hamuro J, Walls AF, et al. Hyperexpression of the high-affinity IgE receptor-beta chain in chronic allergic keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2871–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saini S, Richardson JJ, Wofsy C, Lavens-Phillips, Bochner B, MacGlashan DW., Jr. Expression and modulation of FceRIa and FceRIb in human blood basophils. J. All. Clin. Immunol. 2001;107:832–41. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin S, Cicaia C, Scharenberg AM, Kinet JP. The FceRIb subunit functions as an amplifier of FceRIg-mediated cell activation signals. Cell. 1996;85:985–95. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacGlashan DW., Jr. Endocytosis, Re-cycling and Degradation of Unoccupied FceRI in Human Basophils. J. Leuk. Biol. 2007;82:1003–10. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eckman JA, Sterba PM, Kelly D, Alexander V, Bochner BS, MacGlashan DW, Jr., et al. The Effect of Omalizumab on Basophil and Mast Cell Responses using an Intranasal Cat Allergen Challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert HS, Ornstein L. Basophil counting with a new staining method using alcian blue. Blood. 1975;46:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miura K, Saini SS, Gauvreau G, MacGlashan DW., Jr. Differences in functional consequences and signal transduction induced by IL-3, IL-5 and NGF in human basophils. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2282–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schleimer RP, Derse CP, Friedman B, Gillis S, Plaut M, Lichtenstein LM, et al. Regulation of human basophil mediator release by cytokines. I. Interaction with antiinflammatory steroids. J Immunol. 1989;143:1310–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacGlashan DW, Jr., Xia HZ, Schwartz LB, Gong JP. IgE-regulated expression of FceRI in human basophils: Control by regulated loss rather than regulated synthesis. J. Leuk. Biol. 2001;70:207–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong YE, Menzies-Gow A, Barkans J, Benyahia F, Ou TT, Ying S, et al. Anti-IgE (omalizumab) inhibits late-phase reactions and inflammatory cells after repeat skin allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:558–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Rensen EL, Evertse CE, van Schadewijk WA, van Wijngaarden S, Ayre G, Mauad T, et al. Eosinophils in bronchial mucosa of asthmatics after allergen challenge: effect of anti-IgE treatment. Allergy. 2009;64:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djukanovic R, Wilson SJ, Kraft M, Jarjour NN, Steel M, Chung KF, et al. Effects of treatment with anti-immunoglobulin E antibody omalizumab on airway inflammation in allergic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:583–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1651OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroeder JT, Bieneman A, Chichester K, Hamilton R, Xiao H, Liu MC. Functional Changes in Human Dendritic Cell Antigen-Presenting Cell Activity Following Acute in vivo IgE Neutralization. submitted. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck LA, Marcotte GV, MacGlashan D, Togias A, Saini S. Omalizumab-induced reductions in mast cell Fce psilon RI expression and function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:527–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin H, Boesel KM, Griffith DT, Prussin C, Foster B, Romero FA, et al. Omalizumab rapidly decreases nasal allergic response and FcepsilonRI on basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacGlashan D. Loss of receptors and IgE in vivo during treatment with anti-IgE antibody. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1472–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soundararajan S, Kikuchi Y, Joseph K, Kaplan AP. Functional assessment of pathogenic IgG subclasses in chronic autoimmune urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:815–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliver JM, Tarleton CA, Gilmartin L, Archibeque T, Qualls CR, Diehl L, et al. Reduced FcepsilonRI-Mediated Release of Asthma-Promoting Cytokines and Chemokines from Human Basophils during Omalizumab Therapy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;151:275–84. doi: 10.1159/000250436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]