Abstract

Rationale

IκB kinase (IKK) activates NF-κB which plays a pivotal role in pro-inflammatory response in the lung. NF-κB has been shown to be activated in alveolar macrophages and peripheral lungs of smokers and patients with COPD. We investigated the anti-inflammatory effect of a highly selective and novel IKKβ/IKK2 inhibitor, PHA-408 [8-(5-chloro-2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)isonicotinamido)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-benzo[γ]indazole-3-carboxamide], in lungs of rat in vivo.

Methods

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats were administered orally with PHA-408 (15 and 45 mg/kg) daily for 3 days and exposed to LPS aerosol (once on day 3, 2 h post-last PHA-408 administration) or cigarette smoke (CS; 2 h after PHA-408 administration for 3 days). Animals were sacrificed at 1, 4 and 24 h after the last exposure, and lung inflammatory response and NF-κB activation were measured.

Results

Oral administration of IKKβ/IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 significantly inhibited LPS- and CS-mediated neutrophil influx in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of rats. The levels of pro-inflammatory mediators in BAL fluid (CINC-1) and lungs (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and GM-CSF) were also reduced by PHA-408 administration in response to LPS or CS exposures. The reduced pro-inflammatory response in PHA-408-administered rats was associated with decreased nuclear translocation and DNA binding activity of NF-κB in response to LPS or CS.

Conclusion

These results suggest that IKKβ/IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 is a powerful anti-inflammatory agent against LPS- and CS-mediated lung inflammation.

Keywords: NF-κB, tobacco smoke, IKK2 inhibitor, inflammation, COPD

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is characterized by chronic inflammatory response in the lungs with a progressive and irreversible airflow limitation [1, 2]. COPD is the sixth leading cause of death in the world and is predicted to become the third most common cause of death by 2020 [3, 4]. Unfortunately, none of the currently available drugs are effective in slowing/controlling the progression of COPD or suppressing the pro-inflammatory response in the lung [5]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have been conducted to investigate the therapeutic potential of small molecule inhibitors of signal transduction proteins such as IκB kinase (IKK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase to inhibit various pro-inflammatory pathways [5–12]. We are interested in nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) pathway as therapeutic interventional target since NF-κB is activated in lungs of patients with COPD and plays a pivotal role in chronic pro-inflammatory response seen in COPD [13–18]. NF-κB is an inducible pleiotropic transcription factor that plays a key role in the expression of multiple genes, leading to the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines [12, 19–21]. Therefore, inhibition of CS-induced in lung pro-inflammatory response using small molecule inhibitors for NF-κB activation is an area of research interest for therapeutic approaches and strategies in COPD.

In resting cells, the majority of NF-κB RelA/p65-p50 is bound to IκB protein that holds the complex inactive in the cytoplasm. Upon stimulation/pro-inflammatory stimuli, IKK is activated, which leads to phosphorylation (at Ser32 and Ser36 residues) and subsequent proteasomal degradation of IκB protein. Upon degradation of IκB protein, NF-κB is translocated into the nucleus and binds to the consensus sequences on DNA, which can lead to pro-inflammatory gene transcription. Thus, degradation of IκBα plays a crucial role in activation of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory gene transcription. It has been shown that IKKβ/IKK2-mediated degradation of IκBα and NF-κB activation is induced by a number of pro-inflammatory stimuli including CS, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β [22–25]. Therefore, modulation of NF-κB activity by IKK inhibitors could be useful in controlling the lung inflammation in patients with COPD.

IKK complex consists of IKKα/IKK1, IKKβ/IKK2 and the regulatory subunit IKKγ/NEMO. IKK2 is the primary kinase that phophorylates IκB [10,22] and is required for the cytokine-mediated activation of NF-κB [26]. Due to the critical role of IKK2 in inflammation, a number of small molecule IKK2 inhibitors are under development or in preclinical/clinical trials to prevent inflammation against various pro-inflammatory stimuli in vitro or in vivo [7, 27, 28].

In the light of activation of NF-κB in COPD, we hypothesized that inhibition of endogenous IKK2 using a selective small molecule inhibitor would reduce NF-κB activation and the ensuing lung inflammatory response to pro-inflammatory stimuli. To test this hypothesis, we used acute LPS- and cigarette smoke (CS)-exposure as a model of lung inflammation in rat lungs in vivo to determine the anti-inflammatory effect of a selective IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 [8-(5-chloro-2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)isonicotinamido)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-benzo[γ]indazole-3-carboxamide] [29–31]. PHA-408 is a novel, highly selective IKK2 inhibitor, which has greater selectivity for IKK2 over IKK1 and number of other kinases with the pharmacokinetics of IC50 (40 ± 2 nM) in vitro, EC50 (27–29 mg/kg) [29, 30] with a half-life of 3.4 h and good oral bioavailability (50–60 %) in rats [31]. It is distinct from other IKK2 inhibitors because it binds IKK2 tightly with slow off-rate kinetics/clearance (11.5 ± 2.1 mL/min/kg), and inhibits IKK2 in cell-free systems and living cells with equal potency [29]. Hence, we determined whether targeted inhibition of IKK2 by PHA-408 decreases the LPS- or CS-mediated inflammation in vivo in rat lung in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). PHA-408 [8-(5-chloro-2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)isonicotinamido)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-benzo[γ]indazole-3-carboxamide], a specific inhibitor of IKK2 (Pfizer, St Louis, MO, USA), was used in this study [29–31]. Antibodies specific for IκBα and NF-κB p65 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). GAPDH and Histone H3 were from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA), β-actin was from Calbiochem Inc. (San Diego, CA), and secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA).

2.2. Animals and treatments

Adult Male Sprague-Dawley rats (280 ± 2.5 g) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in the Inhalation Core Facility at the University of Rochester before being exposed to LPS or CS. All experimental protocols were approved and supervised by the University Committee on Animal Research of the University of Rochester.

IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 (15 and 45 mg/kg) or its vehicle consisting of 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose and 0.025% Tween 20 was administered to rats by oral gavage using a balled feeling needle (20 gauge) attached to a 1 ml syringe to rats (6 rats for each group) for 3 days. For LPS challenge, rats were exposed to LPS aerosol dissolved in saline on third day of treatment. In parallel experiments, rats were exposed to CS or filtered air for 3 day after treatment. The doses of PHA-408 were chosen based on its pharmacokinetics with EC50 (27–29 mg/kg in vivo) [29–31]. Rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg (body weight) pentobarbital sodium and sacrificed at 1, 4 and 24 h after last exposure. To compare the effect of PHA-408 with glucocorticoid, rats (4 to 6 rats for each group) were administered with prednisolone (1 mg/kg) or saline via oral gavage for 3 days in a separate experiment and exposed to LPS or CS, respectively. Rats administered with prednisolone were sacrificed at 4 h after last exposure.

2.3. LPS aerosolization to rats

The rats were placed in an individual compartments of a wired cage, which was placed inside a closed plastic box connected to a nebulizer and then were exposed to an aerosol of 1 mg/ml Escherichia coli LPS or saline alone for 8 minutes as described previously [32].

2.4. CS exposure to rats

The smoke was generated from 2R4F research cigarettes containing 11.7 mg of tar or TPM and 0.76 mg of nicotine per cigarette (University of Kentucky). Exposure was performed according to the Federal Trade Commission protocol (1 puff/min of 2 sec duration and 35 ml volume) in a Baumgartner-Jaeger CSM2082i cigarette smoking machine (CH Technologies, Westwood, NJ). Mainstream CS was diluted with filtered air and directed into the exposure chamber. The smoke exposure (TPM per cubic meter of air) was monitored in real-time with a MicroDust Proaerosol monitor (Casella CEL, Bedford, UK) and verified daily by gravimetric sampling. The smoke concentration was set at a nominal value of 600 mg/m3 TPM by adjusting the flow rate of the dilution air. Rats received two 1-h exposures, 1 h apart, according to the Federal Trade Commission protocol (1 puff/min of 2 second duration and 35 ml volume) for 3 days.

2.5. Lung lavage and process of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid

The lungs were lavaged via a catheter inserted into the trachea. Briefly, the thymus, heart, and lung were removed en bloc; and the right lobe was tied off and then instilled with 3 ml of saline for 5 times. First and second aliquots were combined and centrifuged, and the cell-free supernatants (BAL fluid) were frozen for later analyses. Other aliquots were combined, and the supernatant was discarded after centrifugation. The inflammatory cell pellets were combined and resuspended in saline, and the total cell number was determined with a hemocytometer. Differential cell counts (minimum of 500 cells/slide) were performed on Cytospin-prepared slides (Thermo Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) stained with Diff-Quik (Dade Behring, Newark, DE).

2.6. Isolation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from rat lung

One lobe of the right lung was mechanically homogenized in 0.5 ml buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 M EDTA, 0.2 mM NaF, 0.2 mM sodium orthovandate, 1% [vol/vol] nonidet P-40, 0.4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 µg/ml leupeptin) on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 30 sec at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was then transferred to a 1.7 ml ice-cold Eppendorf tube and further centrifuged for 30 sec at 13,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was collected as a cytoplasmic extract. The pellet was resuspended in 200 µl of buffer C (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 50 mM KCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 0.2 mM NaF, 0.2 mM sodium orthovandate, and 0.6 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and placed on the rotator in the cold room for 30 min. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was collected as the nuclear extract and kept frozen at −80°C for Western blotting.

2.7. Cytokine analysis in BAL fluid and lung homogenates

The levels of pro-inflammatory mediator, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 (CINC-1) in BAL fluid was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using respective duo-antibody kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in lung homogenates (100 µl) were measured by the Luminex100 (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX) using Bio-Plex rat cytokine assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assays use microspheres as the solid support for immunoassays. The cytokine levels are expressed as pg/ml in BAL fluid, and pg/mg protein in lung homogenate.

2.8. Protein assay

Protein level in lung samples was measured by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) colorimetric assay as per the manufacture’s instruction (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Linear regression was used to determine the actual protein concentration of the samples.

2.9. Immunoblotting

Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins (20 µg) from rat lung were separated on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis. Separated proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% nonfat dry milk. The membranes were then probed with a specific primary antibody (1:1000 dilution in 2.5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) at 4 °C for overnight. After three washing steps (10 min each), the levels of protein were detected by probing with secondary anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-goat antibody (1:10,000 dilution in 2.5% nonfat dry milk) linked to horseradish peroxidase for 1 hr, and bound complexes were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Equivalent loading of the gel was determined by quantitation of protein as well as by reprobing membranes for actin or GAPDH.

2.10. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

NF-κB DNA binding was determined using the EMSA detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI) in nuclear protein obtained from the rat lungs. Synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase as recommended by the manufacturer. A binding mixture containing 5 µg of nuclear extract, 2.5 µl of 5x binding buffer [50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, and 0.25 mg/ml poly(dI-dC)·poly(dI-dC)], and 1 µl of γ-32P-labeled double-stranded probe was used for the DNA-binding reaction at room temperature for 30 min. To ensure that the detected bands were specific for NF-κB, a 100-fold excess of unlabeled competitor (NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide) and noncompetitor (activator protein-2 consensus oligonucleotide) was added to the reaction mixture before addition of the probe. Gel tracking dye [250 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 0.2% bromphenol blue, and 40% glycerol] was loaded into lane 1, and the DNA-protein complexes were loaded into the remaining wells without tracking dye on the 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography. ImageJ densitometry software (Version 1.41, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used for gel band quantitative densitometric analysis.

2.11. Assay of NF-κB DNA-binding activity

NF-κB binding activity in nuclear extracts was measured using the Trans-AM p65 transcription factor assay kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 2.5 µg of nuclear extracts was incubated with already plate-coated NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. Plates were then washed before addition of anti-p65 antibody. A horseradish peroxidase antibody was used for signal detection and quantification. The absorbance was determined on a spectrophotometer (Microplate reader model 680, Bio-Rad) at 450 nm.

2.12. Statistical analysis

The results are shown as the means ± SEM of three experiments. Statistical analysis of significance was calculated using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for multigroup comparisons using STATVIEW; P < 0.05 considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) reduced the neutrophil influx in BAL fluid in response to LPS and CS exposures in rats

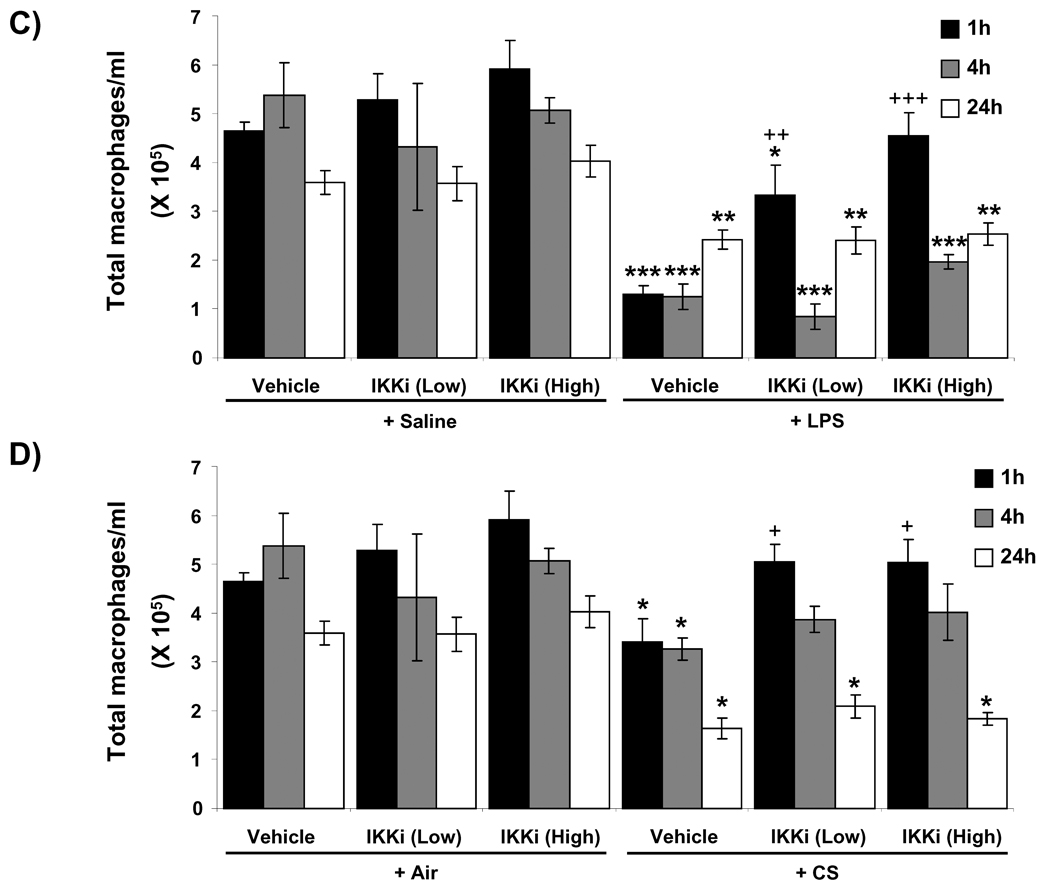

To determine the effect of oral administration of IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) on pro-inflammatory response in vivo, rats were administered with PHA-408 (15 and 45 mg/kg for 2 h) and then exposed to LPS or CS. Inflammatory cell influx into BAL fluid was assessed using Diff-Quik staining. There was no significant effect on the number of neutrophils and macrophages in rats which were administered with PHA-408 without any exposure (Figure 1A and B). In contrast, LPS and CS exposures resulted in significant influx of neutrophils in BAL fluid of rats at 1, 4 and 24 h of post-last exposures (Figures 1A and B), which was accompanied by a significant reduction of macrophages (Figures 1C and D). Administration of PHA-408 (15 and 45 mg/kg) significantly reduced the CS-mediated neutrophil influx at 1, 4 and 24 h of postlast exposures (Figure 1B). High dose of PHA-408 (45 mg/kg) significantly reduced LPS-mediated neutrophil influx at 1, 4 and 24 h of post-last exposures, whereas low dose of PHA-408 (15 mg/kg) significantly (P<0.001) reduced the neutrophil influx only at 1 and 4 h, but not at 24 h of post-last exposures (Figure 1A). PHA-408, at both 15 and 45 mg/kg doses (EC50 27–29 mg/kg, [29–31]) significantly increased the number of macrophages only at 1 h of post-last exposure to LPS or CS, but not at 4 and 24 h, of post-last exposures (Figures 1C and D). These results suggest that PHA-408 is effective in reducing inflammatory cell influx in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 1. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) attenuated LPS- and CS-induced neutrophil influx in BAL fluid of rats.

The neutrophil (A and B) and macrophage (C and D) numbers were counted in Diff-Quick stained cytospin slides, which were prepared using BAL cells collected by lung lavage in rats at 1, 4 and 24 h after LPS (A and C) or CS (B and D) exposures. IKKi (low) and IKKi (high) denote orally administered IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) at the doses of 15 and 45 mg/kg for 3 days, respectively at 2 h before LPS or CS exposure. PHA-408 was dissolved in the vehicle consisting of 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose and 0.025% Tween 20. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant compared with respective saline- or air-exposed control group; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001, significant compared with respective LPS or CS exposed group. IKKi, IKK2 inhibitor.

3.2. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) decreased pro-inflammatory mediator release in BAL fluid in response to LPS or CS exposure

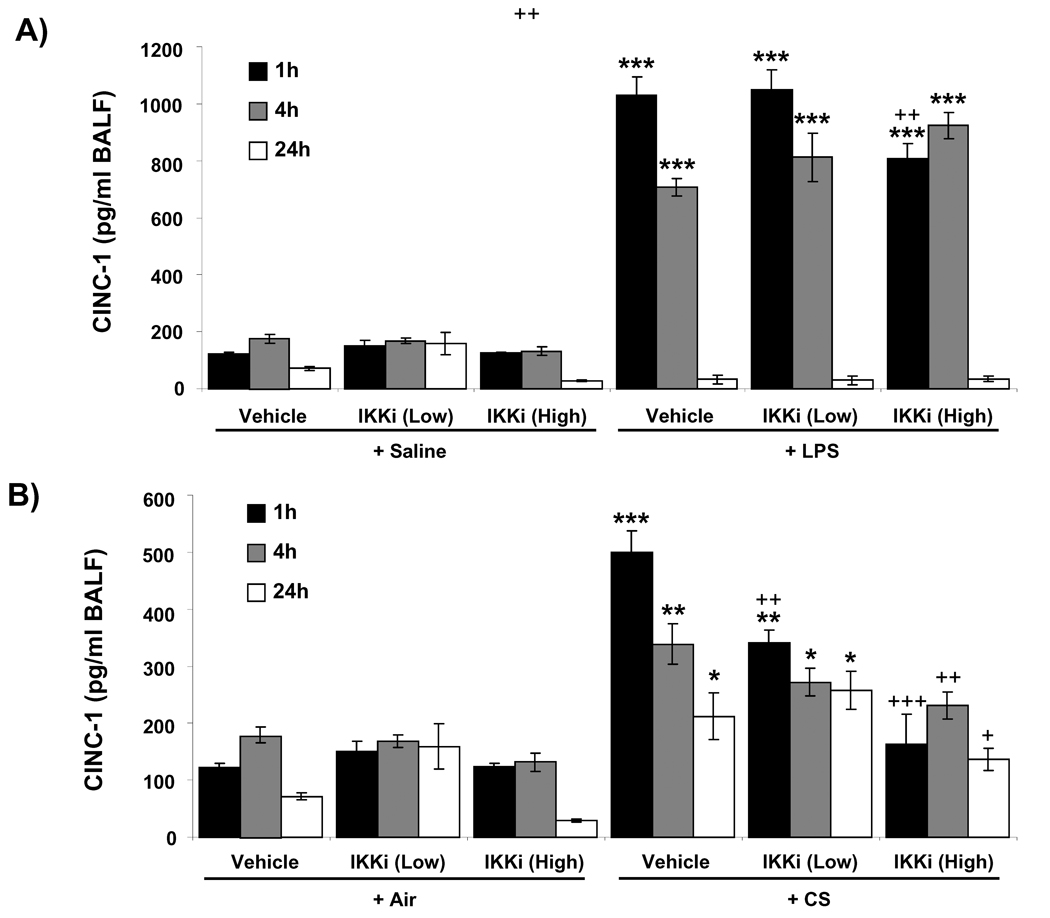

Neutrophil influx in BAL fluid is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. As PHA-408 has a protective role against neutrophil influx in the lung, we determined the effect of PHA-408 on pro-inflammatory mediators, such as the neutrophil chemokine CINC-1 in BAL fluid of rats in response to LPS- and CS-exposures. There was no significant effect on the levels of CINC-1 in BAL fluid of rats which were administered with PHA-408 without any exposure (Figures 2A and B). CINC-1 level was significantly (P<0.001) increased in BAL fluid as early as 1 h of post-last exposure to LPS or CS, which started to decline at 4 h (Figure 2A and B). PHA-408, at 15 and 45 mg/kg, significantly reduced the CS-induced CINC-1 levels at 1 h of post-last exposure; whereas only the high dose of PHA-408 was able to significantly reduce the CINC-1 levels at 4 h and 24 h (Figure 2B). In case of LPS exposure, only the high dose of PHA-408 (45 mg/kg) significantly reduced CINC-1 levels at 1 h of post-last exposure, but not at later time points from 4 h onwards (Figure 2A). These results showed the anti-inflammatory role of PHA-408 in vivo in lung and the pro-inflammatory role of IKK2 in LPS- and CS-mediated inflammation. To confirm the effect of PHA-408 on pro-inflammatory mediators release, we performed Luminex multiplex assay for pro-inflammatory mediators. The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and GM-CSF were augmented in LPS-exposed rat lung at 1 h of post-last exposure, which started to decline at 4 h of post-last exposure (except IL-1β) and reached the basal (control) level at 24 h (Figures 2C – F). Administration of 45 mg/kg of PHA-408 reduced the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and GM-CSF at 1 h and IL-6 at 4 h of post-last exposures in the lung (Figures 2C – F), whereas 15 mg/kg of PHA-408 significantly (P<0.05) reduced the levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β only at 1 h of post-last exposures (Figure 2C – E). These data further confirmed the anti-inflammatory effect of PHA-408 in vivo in rat lungs especially at 1h after LPS/CS exposure.

Figure 2. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) inhibited LPS- and CS-induced increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in BAL fluid of rat lung.

The level of CINC-1 was measured in BAL fluid collected by lung lavage in rat at 1, 4 and 24 h after LPS (A) or CS (B) exposures by ELISA. The levels of NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 (C), TNF-α (D), IL-1β (E), and GM-CSF (F) were measured in lungs obtained from rats at 1, 4 and 24 h post-LPS exposure. Two different doses of orally administered IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408; at 2 h before LPS or CS exposures) were indicated as ‘low’ (15 mg/kg) and ‘high’ (45 mg/kg). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant compared with respective saline- or air-exposed control group; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001, significant compared with respective LPS or CS exposed group. IKKi, IKK2 inhibitor; ND, Not detectable.

3.3. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) decreased the IκBα degradation in the lungs of rats exposed to LPS or CS

IKK2 phosphorylates IκBα, an inhibitor of NF-κB, and triggers its ubiquitination-dependent degradation [33,34]. To confirm the activity of IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408, which is effective in reducing NF-κB-dependent cytokines release effectively at 1 h of post-last exposure to LPS and CS, we investigated the effect of PHA-408 on IκBα degradation. We found that IκBα level was decreased in the cytosolic fraction of LPS- and CS-exposed rat lungs (Figures 3A and B). PHA-408 significantly reduced the degradation of IκBα at a dose of 45 mg/kg at 1 h of post-last exposures to CS and LPS (Figures 3A and B). These results indicate the inhibitory effect of PHA-408 on IKK2-mediated IκBα degradation in vivo in lungs.

Figure 3. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) attenuated LPS- and CS-induced IκBα degradation in rat lung.

IκBα levels were measured by immunoblotting in cytosolic fractions of lungs collected at 1 h post-last exposure to LPS or CS. Gel pictures shown are representative of at least three separate experiments (A). The purity of cytosolic fraction was confirmed by the absence of nuclear protein, histone H3 (data not shown). GAPDH was used as a loading control. After densitometric analysis, the values were normalized against the loading controls (B). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significant compared with respective saline- or air-exposed control group; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, significant compared with respective LPS or CS exposed group. IKKi, IKK2 inhibitor; Sal, saline; Low, 15 mg/kg; High, 45 mg/kg.

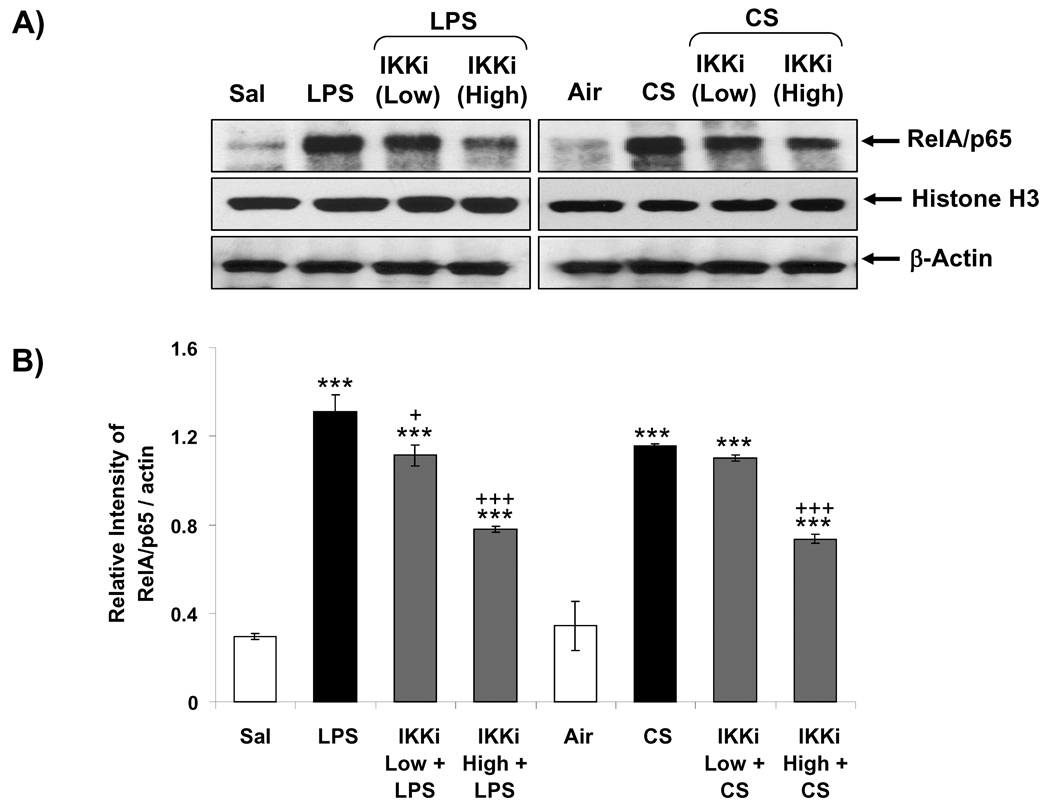

3.4. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) decreased nuclear translocation of NF-κB RelA/p65 in rat lungs in response to LPS or CS exposure

Activation of RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB is mediated by IKK2-induced degradation of IκBα from RelA/p65 complex, which leads nuclear translocation of RelA/p65 [33,34]. To determine the effect of PHA-408 on NF-κB activation, we measured translocation of RelA/p65 into nucleus at 1 h of post-last exposure to LPS or CS. Nuclear levels of RelA/p65 were significantly increased in rat lung in response to LPS and CS exposures (Figures 4A and B). Oral administration of PHA-408 reduced the RelA/p65 levels in the nucleus in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 4A and B). High dose of PHA-408 (45 mg/kg) significantly reduced LPS- and CS-mediated increased levels of RelA/p65 in the nucleus (P<0.001). These results demonstrated that inhibition of IKK2 by PHA-408 led to decreased nuclear translocation and inactivation of RelA/p65 in response to LPS- and CS-exposures.

Figure 4. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) decreased LPS- and CS-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB RelA/p65 in rat lung.

Nuclear levels of RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB were measured by immunoblotting at 1 h after LPS or CS exposure. The purity of nuclear fraction was shown by the presence of histone H3 (nuclear protein) and the absence of cytoskeleton protein, α-tubulin (data not shown). β-Actin was used as a loading control. After densitometric analysis, the values were normalized against the loading controls (B). Gel pictures shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). ***P < 0.001, significant compared with respective saline- or air-exposed control group; +P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001, significant compared with respective LPS or CS exposed group. IKKi, IKK2 inhibitor; Sal, saline; Low, 15 mg/kg; High, 45 mg/kg.

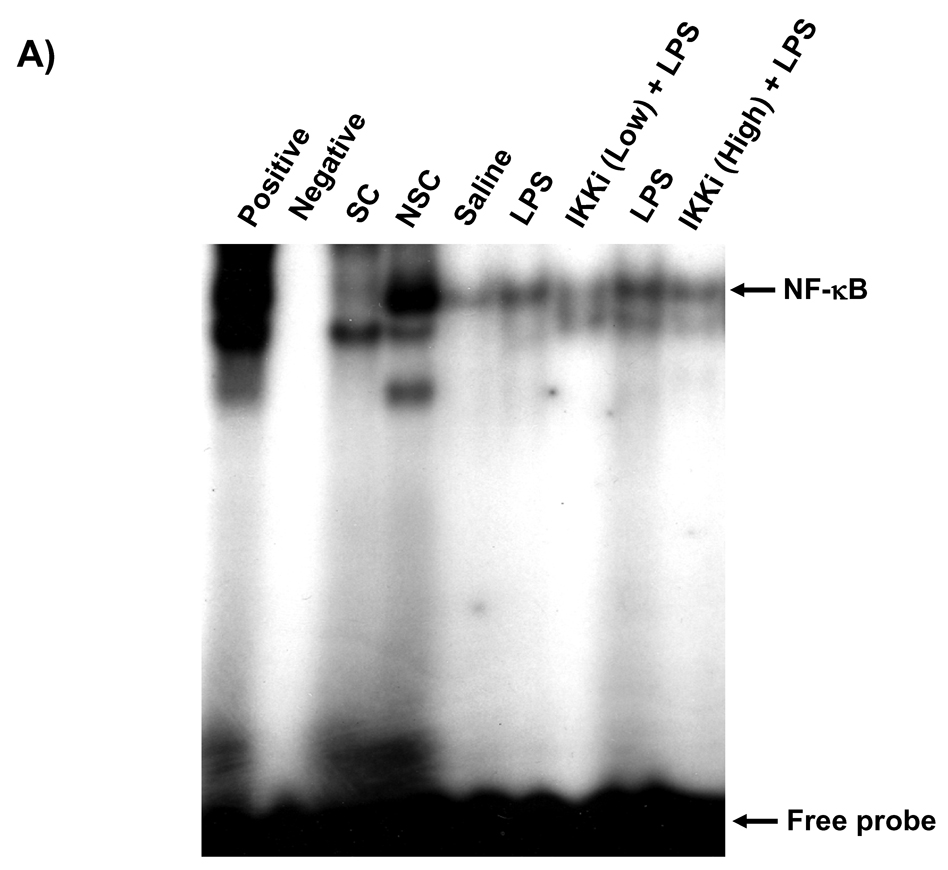

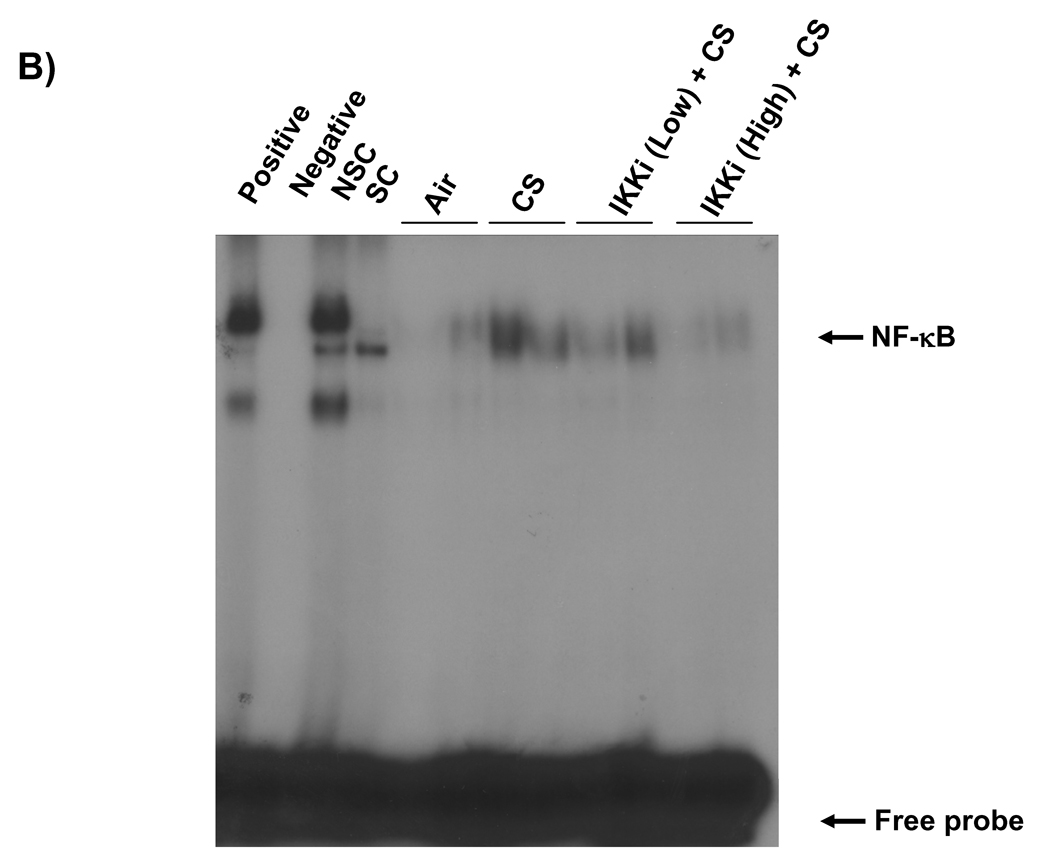

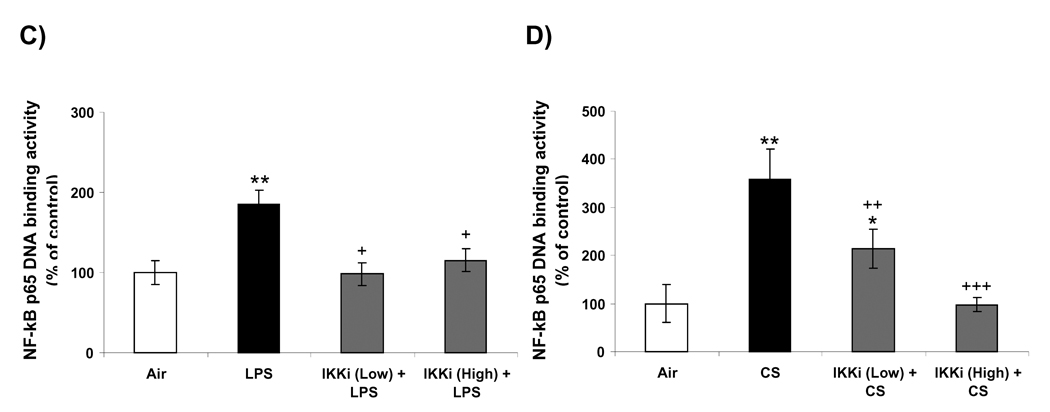

3.5. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) reduced LPS- and CS-induced NF-κB-DNA binding in rat lungs

NF-κB-DNA binding in the nucleus is essential for the NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory gene transcription in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli [35]. We measured the nuclear NF-κB-DNA binding by EMSA and Trans-AM p65 transcription factor assay in rat lungs in response to LPS- or CS exposures. LPS or CS exposure increased the DNA binding activity of NF-κB in the nucleus of rat lung at 1 h of post-last exposure by EMSA (Figures 5A and B). Analysis of the densitometry of NF-κB-shifted bands showed a significant 1.9-fold increase (P<0.01) in LPS and 3.6-fold increase (P<0.01) in CS (Figures 5C and D). Oral administration of PHA-408 at both 15 and 45 mg/kg doses decreased the DNA binding activity of NF-κB which was induced by CS and LPS. In parallel experiments, we confirmed the effect of PHA-408 on LPS- or CS-induced increase of NF-κB DNA binding activity by Tran-AM p65 DNA binding assay. The levels of NF-κB p65 DNA binding activity was increased in LPS or CS-exposed rat lung (2.8-fold change; P<0.001 and 1.9-fold change; P<0.01, respectively) compared with respective control groups (Figures 5E and F). Administration of PHA-408 significantly reduced LPS- or CS-induced increase in NF-κB p65 DNA binding activity at a dose of 45 mg/kg (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively). The specificity of the assay was confirmed using wild-type NF-κB consensus oligonucleotides (0.062 ± 0.008 OD 450 nm), which showed a 2.6-fold increase in activated NF-κB concentration as compared mutated oligonucleotide (0.024 ± 0.008 OD 450 nm). These data suggested that IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 decreased the NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory gene expression by reducing the NF-κB-DNA binding.

Figure 5. IKK2 inhibitor (PHA-408) decreased LPS- or CS-induced NF-κB-DNA binding in rat lung.

NF-κB-DNA binding was measured by EMSA in nuclear proteins form LPS (A) or CS (B) exposed rat lung using γ-32P-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide. The specificity of NF-κB signals was determined by specific and nonspecific competitor reactions by adding non-labeled NF-κB (specific) and AP-1 (non-specific) oligonucleotides to HeLa nuclear extracts (before the addition of γ-32P labeled NF-κB oligonucleotides). Positive and negative control reactions were also performed using HeLa nuclear extracts and water, respectively. Quantification of band intensities from three independent experimental results was determined by a densitometry (C and D). Gel pictures shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. NF-κB DNA-binding activity in response to LPS (E) or CS (F) exposure in the lung nuclear protein was determined using Trans AM transcription factor p65 ELISA kit. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant compared with respective saline- or air-exposed control groups; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001, significant compared with respective LPS or CS exposed group. Positive, Positive control; Negative, negative control; SC, Specific competitor; NSC, Nonspecific competitor; IKKi, IKK2 inhibitor; Low, 15 mg/kg; High, 45 mg/kg.

3.6. Corticosteroid reduced inflammatory response induced by LPS but not CS in rat lung

Corticosteroids are one of the major therapeutic agents used against chronic respiratory diseases such as COPD. To compare the pharmacologic effect of corticosteroids on LPS or CS-induced inflammation with PHA-408, corticosteroid (prednisolone, 1 mg/kg) was administered to rats and then exposed to LPS and CS. We analyzed the cells in the BAL fluid to assess the changes in number of total neutrophils and macrophages. There were no significant differences in number of neutrophils and macrophages in rats which were administered only with prednisolone without LPS and CS exposures compared with controls (data not shown). Prednisolone treatment significantly decreased LPS-induced neutrophils influx (LPS group: 3.1 ± 0.36 × 105 cell/ml; LPS + prednisolone: 2.3 ± 0.45 × 105 cell/ml, P<0.01). However, prednisolone treatment did not show any significant decrease in neutrophils influx (1.8 ± 0.29 × 104 cell/ml) compared with only CS exposed group (2.0 ± 0.23 × 104 cell/ml). Furthermore, prednisolone treatment did not show any difference in macrophages count in BAL fluid in response to LPS and CS exposures (data not shown). These data are in agreement with previous report [21] showing the inefficacy of corticosteroid in controlling CS-induced lung inflammation. These results suggest the mechanism of PHA-408 against LPS or CS-induced inflammation could be different to that of corticosteroids.

4. Discussion

Abnormal underlying lung inflammation plays a critical role in the onset and progression of COPD, which is associated with increased activation of NF-κB [15, 16, 18, 36]. Systemic and lung levels of NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α and IL-6 are increased in patients with COPD [37,38]. Hence, NF-κB activation and its involvement in chromatin remodeling are key events in regulating pro-inflammatory gene expression in patients with COPD [13, 14, 39]. A number of small molecular weight inhibitors against IKK, NF-κB inducing kinase and IκB ubiquitin ligase have been tested to identify and validate a novel anti-inflammatory agent to inhibit NF-κB-mediated inflammation [5]. One such inhibitor is PHA-408 which has IKK2-specific anti-inflammatory effects both in vitro and in vivo [29–31]. In this study, we used this highly selective and novel IKK2 inhibitor, PHA-408 [29-31], to determine its effect on inhibition of lung NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory response against LPS or CS in rats.

Acute exposures of LPS and CS induced pro-inflammatory response in the lung which was evident from the increased inflammatory neutrophil influx and increased CINC-1 levels in BAL fluid of rats. However, the number of macrophages was decreased in BAL fluid in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli (LPS and CS) which might be due to the migration of macrophages into the interstitium of the lung [23]. LPS- and CS-mediated inflammation was stronger at 1 and 4 h as compared to 24 h of post-last exposures. Furthermore, LPS aerosolization was more effective in inducing inflammatory cell influx and cytokine levels as compared to CS exposure. Inhibition of IKK2 by PHA-408 significantly reduced the inflammatory response of the lung by decreasing the number of neutrophils and the levels of pro-inflammatory mediator CINC-1 in BAL fluid in response to LPS- and CS-exposures. The anti-inflammatory effect of PHA-408 was confirmed by showing the reduced levels of LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF in rat lung. The analysis of BAL fluid and lung homogenates indicated that the anti-inflammatory effect of PHA-408 was potent at 1 h, rather than 4 and 24 h, of post-last exposures to LPS or CS. Our findings corroborate with the previous report showing that PHA-408 decreased serum TNF-α levels at 90 min after LPS challenge in rat lung by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IκBα [28]. It has been reported that plasma concentration of PHA-408 reached maximum immediately after the oral administration and started to decline from 12 h with dissociation t½ of IKK2-PHA-408 complex was approximately 3.4 h in rats [29, 31]. This might be a reason for the strong anti-inflammatory activity of PHA-408 seen at 1 h of post-last exposure to pro-inflammatory stimuli, rather than 4 and 24 h. Our findings not only showed the anti-inflammatory effect of PHA-408, but also demonstrated the critical role of IKK2 in LPS- and CS-mediated pro-inflammatory response in the lung.

To understand the molecular mechanism of the IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 in reducing NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokines release and subsequent inflammatory cell influx, we tested the effect of PHA-408 on IκBα degradation. In consistent with previous reports [23, 40], acute LPS- and CS-exposures resulted in IκBα degradation in rat lung, which was associated with increased nuclear translocation of RelA/p65. IKK2 activation was reported to play a central role in CS- and LPS-mediated IκBα phosphorylation and degradation [23–25]. We found that IKK2 inhibition by PHA-408 decreased IκBα degradation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB in rat lung in response to LPS- and CS-exposures. We predict that PHA-408 binds with endogenous IKK2 and thereby inhibits IκBα phosphorylation which leads to stabilization of IκBα and reduction in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB [29]. PHA-408-mediated reduction of nuclear translocation of RelA/p65 was associated with reduction in nuclear NF-κB-DNA binding in response to LPS and CS exposures. Hence, the inhibitory effect of PHA-408 against NF-κB activity and pro-inflammatory mediator release was confirmed by its effect in reducing LPS- and CS-mediated NF-κB activation, and NF-κB-DNA binding in the nucleus of rat lung.

Despite of the effectiveness of corticosteroid in controlling NF-κB-mediated inflammation, COPD is highly unresponsive to corticosteroids and exhibits a largely steroid-resistant pattern of inflammation [41]. Accumulating evidences show that NF-κB inhibitors, such as decoy oligonucleotides, proteasome inhibitor and small molecule inhibitors of IKK2 may have an efficacy in animal model of steroid-resistant chronic inflammatory conditions disease [42,43]. Furthermore, a number of small molecule IKK2 inhibitors are in preclinical/clinical trials to prevent inflammation against various pro-inflammatory stimuli in vitro or in vivo [7, 27, 28]. In this study, we compared the efficacy of IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 over CS-induced inflammation with a corticosteroid (prednisolone). Prednisolone treatment significantly decreased LPS-induced neutrophil influx but unable to inhibit lung neutrophil influx in response to CS exposure. In contrast, PHA-408 showed significant decrease of neutrophil influx in response to both of LPS and CS exposures. These results suggest the mechanism of PHA-408 against LPS or CS-induced inflammation could be different to that of corticosteroids.

In summary, a selective IKKβ/IKK2 inhibitor, PHA-408, effectively reduced LPS- and CS-induced acute lung inflammatory response in rat. The mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of PHA-408 is due to the inhibition of IκBα degradation and subsequent reduction in RelA/p65 nuclear translocation and activity of NF-κB. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that administration of a selective IKK2 inhibitor, PHA-408, exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in vivo in rodent lung against CS-exposures in a dose- and time-dependent manner. However, it remains to be seen whether IKK2 inhibitor PHA-408 is equally effective in controlling inflammation in chronic CS exposure animal models, and overcoming steroid-resistance in cigarette smoke/oxidative stress models and subsequent pathological changes. Similarly, it is also known whether multiple kinase pathways, such as p38 kinase and PI-3 kinase which are activated in patients with COPD can also be targeted along with IKK2 inhibitor for maximum beneficial anti-inflammatory effects [44–46]. Lastly, phase I clinical trails are needed to test the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions in COPD.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH - National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL085613, and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center Grant ES-01247.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burchfiel CM, Marcus EB, Curb JD, Maclean CJ, Vollmer WM, Johnson LR, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on longitudinal decline in pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1778–1785. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saetta M. Airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:S17–S20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ, Kleinert S. COPD--a neglected disease. Lancet. 2004;364:564–565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16866-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:523–532. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00124605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PJ, Hansel TT. Prospects for new drugs for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364:985–996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito K, Caramori G, Adcock IM. Therapeutic potential of phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase inhibitors in inflammatory respiratory disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:1–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birrell MA, Wong S, Hardaker EL, Catley MC, McCluskie K, Collins M, et al. IkappaB kinase-2-independent and -dependent inflammation in airway disease models: relevance of IKK-2 inhibition to the clinic. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1791–1800. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicherla S, Fitzgerald MF, Spicer D, Woodman P, Ma JY, Kapoun AM, et al. p38alpha-selective mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor SD-282 reduces inflammation in a subchronic model of tobacco smoke-induced airway inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:921–929. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton R, Holden NS, Catley MC, Oyelusi W, Leigh R, Proud D, et al. Repression of inflammatory gene expression in human pulmonary epithelial cells by small-molecule IkappaB kinase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:734–742. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adcock IM, Chung KF, Caramori G, Ito K. Kinase inhibitors and airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:118–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer WI, Yao H, Rahman I. Future therapeutic treatment of COPD: struggle between oxidants and cytokines. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2:205–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao H, de Boer W, Rahman I. Targeting Lung Inflammation: Novel Therapies for the Treatment of COPD. Curr Respir Med Rev. 2008;4:57–68. doi: 10.2174/157339808783497873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Oates T, Capelli A, Lusuardi M, Gnemmi I, et al. Increased expression of nuclear factor-kappaB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:556–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00272002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caramori G, Romagnoli M, Casolari P, Bellettato C, Casoni G, Boschetto P, et al. Nuclear localisation of p65 in sputum macrophages but not in sputum neutrophils during COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2003;58:348–351. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajendrasozhan S, Yang SR, Edirisinghe I, Yao H, Adenuga D, Rahman I. Deacetylases and NF-kappaB in redox regulation of cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation: epigenetics in pathogenesis of COPD. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:799–811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajendrasozhan S, Yang SR, Kinnula VL, Rahman I. SIRT1, an antiinflammatory and antiaging protein, is decreased in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:861–870. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1269OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szulakowski P, Crowther AJ, Jimenez LA, Donaldson K, Mayer R, Leonard TB, et al. The effect of smoking on the transcriptional regulation of lung inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:41–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-725OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin AS., Jr Series introduction: the transcription factor NF-kappaB and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:3–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes PJ. Cytokine modulators as novel therapies for airway disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;34 Suppl:67s–77s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00229901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marwick JA, Kirkham PA, Stevenson CS, Danahay H, Giddings J, Butler K, et al. Cigarette smoke alters chromatin remodeling and induces proinflammatory genes in rat lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:633–642. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0006OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li ZW, Chu W, Hu Y, Delhase M, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, et al. The IKKbeta subunit of IkappaB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor kappaB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1839–1845. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao H, Edirisinghe I, Yang SR, Rajendrasozhan S, Kode A, Caito S, et al. Genetic ablation of NADPH oxidase enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1222–1237. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connell MA, Bennett BL, Mercurio F, Manning AM, Mackman N. Role of IKK1 and IKK2 in lipopolysaccharide signaling in human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30410–30414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawiger J, Veach RA, Liu XY, Timmons S, Ballard DW. IkappaB kinase complex is an intracellular target for endotoxic lipopolysaccharide in human monocytic cells. Blood. 1999;94:1711–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee KF, Verma IM. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishore N, Sommers C, Mathialagan S, Guzova J, Yao M, Hauser S, et al. A selective IKK-2 inhibitor blocks NF-kappa B-dependent gene expression in interleukin-1 beta-stimulated synovial fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32861–32871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coish P, Wickens P, Lowinger T. Small molecule inhibitors of IKK kinase activity. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2006;16:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mbalaviele G, Sommers CD, Bonar SL, Mathialagan S, Schindler JF, Guzova JA, et al. A novel, highly selective, tight binding IkappaB kinase-2 (IKK-2) inhibitor: a tool to correlate IKK-2 activity to the fate and functions of the components of the nuclear factorkappaB pathway in arthritis-relevant cells and animal models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:14–25. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sommers CD, Thompson JM, Guzova JA, Bonar SL, Rader RK, Mathialagan S, et al. Novel tight-binding inhibitory factor-kappaB kinase (IKK-2) inhibitors demonstrate target-specific anti-inflammatory activities in cellular assays and following oral and local delivery in an in vivo model of airway inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:377–388. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiang PC, Kishore NN, Thompson DC. Combined use of pharmacokinetic modeling and a steady-state delivery approach allows early assessment of IkappaB kinase-2 (IKK- 2) target safety and efficacy. J Pharm Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jps.21909. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao H, Yang SR, Edirisinghe I, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Adenuga D, et al. Disruption of p21 attenuates lung inflammation induced by cigarette smoke, LPS, and fMLP in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:7–18. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 Suppl:S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. IkappaB kinases: key regulators of the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen LF, Greene WC. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown V, Elborn JS, Bradley J, Ennis M. Dysregulated apoptosis and NFkappaB expression in COPD subjects. Respir Res. 2009;10:24–35. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agusti AG, Noguera A, Sauleda J, Sala E, Pons J, Busquets X. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:347–360. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00405703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edwards MR, Bartlett NW, Clarke D, Birrell M, Belvisi M, Johnston SL. Targeting the NF-kappaB pathway in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CS, Kawada T, Kim BS, Han IS, Choe SY, Kurata T, et al. Capsaicin exhibits anti-inflammatory property by inhibiting IkB-a degradation in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. Cell Signal. 2003;15:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adenuga D, Rahman I. Oxidative Stress, Histone Deacetylase and Corticosteroid Resistance in Severe Asthma and COPD. Curr Respir Med Rev. 2007;3:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Stefano D, De Rosa G, Maiuri MC, Ungaro F, Quaglia F, Iuvone T, et al. Oligonucleotide decoy to NF-kappaB slowly released from PLGA microspheres reduces chronic inflammation in rat. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karimi K, Sarir H, Mortaz E, Smit JJ, Hosseini H, De Kimpe SJ, et al. Toll-like receptor- 4 mediates cigarette smoke-induced cytokine production by human macrophages. Respir Res. 2006;7:66–78. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doukas J, Eide L, Stebbins K, Racanelli-Layton A, Dellamary L, Martin M, et al. Aerosolized phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma/delta inhibitor TG100-115 [3-[2,4- diamino-6-(3-hydroxyphenyl)pteridin-7-yl]phenol] as a therapeutic candidate for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp The. 2009;328:758–765. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kent LM, Smyth LJ, Plumb J, Clayton CL, Fox SM, Ray DW, et al. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease macrophage inflammatory gene expression by dexamethasone and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor N-cyano-N'-(2-{[8-(2,6-difluorophenyl)-4-(4-fluoro-2-methylphenyl)-7- oxo-7,8-dihydropyrido[2,3-d] pyrimidin-2-yl]amino}ethyl)guanidine (SB706504) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:458–468. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.142950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fox JC, Fitzgerald MF. The role of animal models in the pharmacological evaluation of emerging anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of COPD. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]