Abstract

We report a case of traumatic optic neuropathy accompanying a grease gun injury to the orbit. A 48-year-old man with a grease gun injury visited our clinic with decreased visual acuity, proptosis and limited extraocular movement (EOM). Orbital CT revealed a crescent mass of fat in the medial intraconal space. The grease was exuded from a lacerated conjunctival wound. The visual evoked potential (VEP) test demonstrated a decreased response in the left eye. Proptosis and EOM were improved after surgical removal of the grease. Systemic high-dose corticosteroid therapy was administered for suspected traumatic optic neuropathy, after which VEP nearly recovered, while visual acuity was slightly improved. A second surgery for traumatic cataract did not further improve visual acuity.

Keywords: Optic nerve diseases, Orbit, Penetrating eye injuries

Grease is a thixotropic lubricant consisting of a calcium, sodium or lithium-soap jelly emulsified with mineral oil. It liquefies when agitated and solidifies when at rest. Grease guns are commonly used workshop tools used to apply grease under pressure to the part being lubricated. The pressure increases up to 621-1034 kPa and is sufficient to eject grease at a velocity comparable to the muzzle velocity of a rifle bullet.

Grease gun injuries cause mechanical and chemical damage. Chemical damage of tissues caused by injected grease is less than those of other chemical substances due to the high viscosity and low tissue toxicity of grease. However, the high pressure can result in focal penetration followed by blunt dissection along the tissue planes. The most common sites of injury are the fingers and hand; however, any part of the body can be involved. Grease gun injuries of the orbit are very rare, and only six cases have been published to our knowledge [1-5].

We report a case of intraconal grease gun injury accompanied by traumatic optic neuropathy.

Case Report

A 48-year-old man visited the emergency department of our clinic after an accidental grease gun injection injury to his left eye. He complained of decreased visual acuity and pain. Marked swelling and abrasions of the eyelids were noted. Visual acuity was hand motion in the left eye and 20/20 in the right eye. The pupillary light reflex of the left eye was sluggish, and extraocular movement (EOM) was extremely limited in all directions. Exophthalmometry readings showed 4.5 mm of proptosis in the left eye (Fig. 1). Slit lamp examination showed inflammatory reactions in the anterior chamber, microhyphema and lens subluxation. A T-shaped full thickness conjunctival laceration with exposed medial rectus muscle was also found with exuded grease from the wound (Fig. 2). Intraocular pressure was difficult to measure as the eyelid was too tense to open. Palpation suggested that intraocular pressure was very high. The fundus was bulged forward by a mass-like material behind it but showed no other abnormal findings. A lateral canthotomy and cantholysis were performed to reduce the orbital pressure. Orbital CT (non-enhancing) revealed distortion and lateral displacement of the globe by a low-attenuated crescent mass of fat density in the medial intraconal space (Fig. 3). B-scan findings were correlated with CT findings. Intravenous antibiotics (i.v. amikacin 100 mg, cephradine 1 g, q.d.), systemic steroid (p.o. mehtylprednisolone 24 mg, q.d.) and topical antibiotics (levofloxacin, tobramycin 0.3%, q.i.d.) were immediately initiated.

Fig. 1.

Appearance just after the accident showing eyelid swelling, chemosis and extreme limitations of extraocular movement (EOM) in all directions.

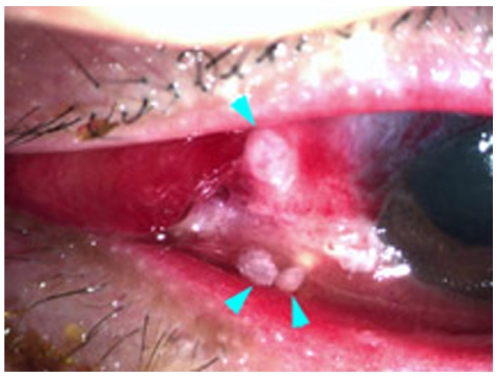

Fig. 2.

Solidified grease (arrow heads) extruded from the conjunctival laceration wound.

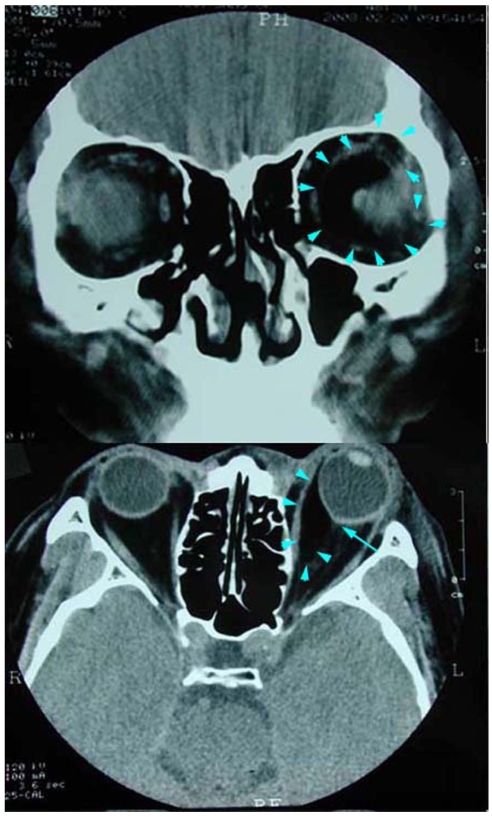

Fig. 3.

Orbital CT just after the accident. The globe is laterally deviated by a low-attenuated crescent-shaped area (-109 HU, arrow heads) in the medial intraconal space. The volume effect of this area causes proptosis, which results in distortion of the posterior part of the globe (arrow) and optic nerve extension. Bony structures and extraocular muscles appear intact.

Surgical exploration was performed through the conjunctival laceration wound on the second hospital day. Solidified fatty foreign bodies were found and removed as much as was possible (Fig. 4). The conjunctiva was repaired after copious irrigation. Along the medial plane of the globe, the foreign bodies seemed to contain liquefied subconjunctival tissue with high pressure.

Fig. 4.

Solidified grease surgically removed from the intraconal area through the conjunctival wound.

EOM, proptosis and lens subluxation were improved the following day. Follow-up orbital CT confirmed a reduced amount of foreign material and decreased global displacement. The remainder of the foreign material was difficult to identify due to retrobulbar hemorrhage. Intraocular pressure measured 20 mmHg by applanation tonometry.

Visual acuity remained decreased, and a visual evoked potential (VEP) test on the third post-op day showed nearly nonrecordable amplitudes in the left eye. The P100 latency in the left eye (130 ms) was delayed compared to that in the right eye (114 ms), and the N75 to P100 amplitudes were reduced (2.15 µV) compared to that in the right eye (13.5 µV). Systemic high-dose corticosteroid therapy (i.v. methylprednisolone 250 mg, q.i.d, three days) was started on the third post-op day to treat the suspected traumatic optic neuropathy. Visual acuity was improved from hand motion to 0.1 two days later.

One month after the operation, the visual acuity of the left eye was 0.1. Exophthalmometry readings were 18 mm in both eyes, and EOM was further improved. Intraocular pressure measured 27 mmHg in the left eye by Goldmann tonometry. The cup to disc ratio was about 0.4, and there was no angle recession or retinal nerve fiber layer defect. The patient was instructed to apply dorzolamide hydrochloride/timolol maleate (Cosopt®; Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). MRI showed bubble-like, non-enhancing lesions surrounded by enhancing areas suggestive of an inflammatory reaction. The adjacent rectus muscles appeared slightly compressed and showed fat infiltration (Fig. 5).

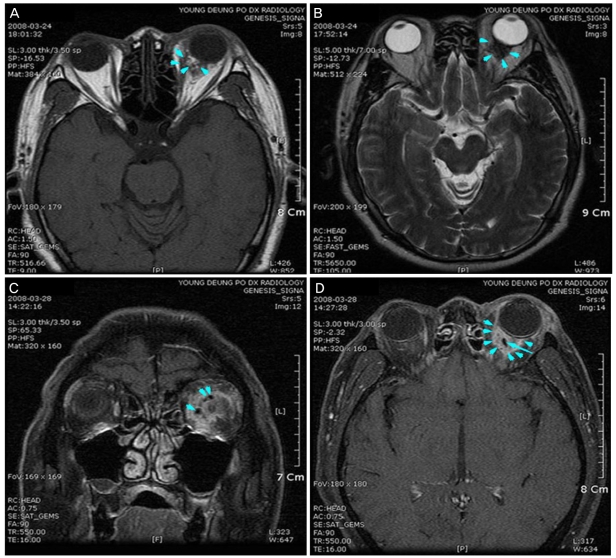

Fig. 5.

MRI 1 month after the surgical removal of the grease. Multiple bubble-like cystic lesions (arrows) are surrounded by enhancing areas presumed to be inflammatory reactions (arrow heads) to foreign bodies. Adjacent rectus muscles look slightly compressed. On the T1-weighted image (A), cystic lesions show high signal intensity which resembles that of intraconal fat. On the T2-weighted image (B), the lesions are difficult to distinguish from the surrounding area because of similar low signal intensities. On the fat saturation images (C, D), on the other hand, both the cystic and surrounding lesions are well demarcated and distinguished from the intraconal fat.

After another two months, the EOM was much improved, and the VEP test showed a recovered response despite a maintained decrease in visual acuity (Fig. 6). Intraocular pressure was maintained within high-normal limits with constant use of dorzolamide hydrochloride/timolol maleate. The patient complained of being dazed, likely because of a fixed dilated pupil and anterior capsular lens opacity. He underwent vitrectomy, lensectomy and intraocular lens implantation. One month after the second operation, however, his best corrected visual acuity was still 0.1 in the left eye.

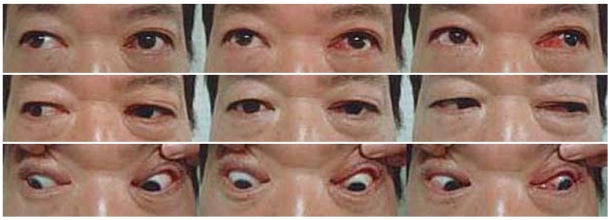

Fig. 6.

Appearance 3 months after the surgical removal of grease showing markedly improved extraocular movement and proptosis in the left eye. Limitation in the medial gaze is still shown.

Discussion

In the late 1950s, the widespread use of high pressure paint sprays and hydraulic systems increased the incidence of high pressure injection injuries. However, grease gun injuries to the orbit have rarely been reported. The present case is the seventh report throughout the world, and the first in Korea to our knowledge.

The first such case was reported in 1964 [1]. A mechanic with grease gun injury to the orbit presented with visual disturbance, proptosis, superior visual field loss and bilateral disc edema and venous engorgement. Despite long-term steroid treatment and orbitotomy, there was no postoperative improvement.

In 1988, a 19-year-old man was hit by a jet of oil from a grease gun, resulting in marked proptosis and decreased visual acuity to light perception [2]. Daily irrigation and drainage followed by aspiration of the grease improved the proptosis dramatically and also improved visual acuity to 1.0 within six weeks.

Goel et al. [3] reported two cases that occurred in 1988 and 1989. In the former case, the ejected grease ruptured the globe and broke the medial wall and floor. An enucleation was followed by ethmoidectomy, sphenoidectomy, inferior turbinectomy and antrostomy. In the latter case, mild proptosis, diplopia and swelling was improved three weeks after an anterior orbitotomy.

According to the report of Gekeler et al. [4] in 2005, reduced visual acuity resulting from grease gun injury normalized after six weeks of conservative care. Limitation of ocular motility, diplopia or visual field defect was not seen within the following 11 months. Antonio et al. concluded that intraconal grease should not necessarily be removed in the absence of symptoms.

The sixth case was reported recently in China [5]. The patient with a grease gun injury underwent orbital exploration. His visual acuity and EOM were improved after complete removal of the grease. Immediate and thorough removal of the grease was of great importance in this case.

In the present case, an immediate diagnosis was somewhat difficult. The grease gun is an unfamiliar tool and the intraconal mass on CT resembled orbital fat in density. It was helpful to understand the mechanism of a grease gun being operated under high pressure. We presumed that the grease had dissected subconjunctival tissue along the medial plane of the globe, and this presumption was supported by CT findings and fatty material extruding from the conjunctival wound. There was marked proptosis and EOM limitation. Surgical removal was inevitable and actually relieved the symptoms. Traumatic optic neuropathy appeared to accompany grease gun injury in this case. Though high-dose corticosteroid therapy is not of proven benefit to traumatic optic neuropathy itself, it might allow for early visual improvement due to a reduction in edema [6,7]. Some improvement in visual acuity was presumed to be the result of high-dose corticosteroid therapy rather than due to the surgical removal of the grease in this case.

Despite incomplete removal of the grease, additional removal was not attempted because EOM, proptosis and global displacement had improved and VEP recovered after time. Moreover, the remainder of the grease caused no active inflammation, and visual acuity was not expected to improve after further surgery. However, it is well known that oily substances cause sclerosing lipogranulomatous inflammation when injected subcutaneously whether for cosmetic reasons or unintentionally. Therefore, the remaining material should be followed-up persistently even if it is not presently troublesome.

It is notable that the prompt removal of grease improved the ocular symptoms and signs except for visual acuity. Visual disturbance continued after VEP recovered. Traumatic cataract might be one factor but, contrary to our expectations, cataract surgery did not improve visual acuity.

The previous and present cases demonstrate a broad spectrum of high pressure grease gun injuries to the orbit. If external wounds or ocular symptoms are not severe, then rare retrobulbar fatty foreign bodies can be overlooked. Careful history taking is important to establish the diagnosis. Imaging studies using CT or MRI are necessary to confirm grease deep within the orbit. MRI is particularly valuable for illustrating the extent of the infiltrate [2]. Intravenous antibiotics and systemic steroids are recommended [3]. Most authors have reported that surgical removal is necessary but Gekeler et al. [4] insisted that close observation was sufficient in the absence of ocular symptoms. The decision to operate should be made according to the general ocular conditions as the tissue toxicity of grease itself is limited.

Footnotes

This case was presented at the 2008 Annual Case Conference of the Korean Society of Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery held in Jinju in April.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Dallas NL. Chronic granuloma of the orbit caused by grease-gun injury. Br J Ophthalmol. 1964;48:158–159. doi: 10.1136/bjo.48.3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boukes RJ, Stilma JS, de Slegte RG, Zonneveld FW. Grease-gun injury of the orbit: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Doc Ophthalmol. 1987;67:273–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00144281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel N, Johnson R, Phillips M, Westra I. Grease gun injuries to the orbit and adnexa. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;10:211–215. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gekeler F, Cruz AA, de Paula SA, et al. Intraconal grease-gun injury: a therapeutic dilemma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:393–395. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000175017.30029.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Lu X, Xiao L. Delayed presentation of grease-gun injury to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:154–156. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181659caf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin LA, Beck RW, Joseph MP, et al. The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1268–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinsapir KD. Treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy with high-dose corticosteroid. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:65–67. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000204646.94991.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]