Abstract

Behavioral couples therapy (BCT), a treatment approach for married or cohabiting drug abusers and their partners, attempts to reduce substance abuse directly and through restructuring the dysfunctional couple interactions that frequently help sustain it. In multiple studies with diverse populations, patients who engage in BCT have consistently reported greater reductions in substance use than have patients who receive only individual counseling. Couples receiving BCT also have reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction and more improvements in other areas of relationship and family functioning, including intimate partner violence and children’s psychosocial adjustment. This review describes the use of BCT in the treatment of substance abuse, discusses the intervention’s theoretical rationale, and summarizes the supporting literature.

Historically, the treatment community and the public at large have viewed alcoholism and other drug abuse as individual problems most effectively treated on an individual basis. However, during the last three decades, professionals and the public have come to recognize family members’ potentially crucial roles in the origins and maintenance of addictive behavior. Treatment providers and researchers alike have begun conceptualizing drinking and drug use from a family systems perspective and treating the family as a way to address an individual’s substance abuse.

In the early 1970s, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) described couples and family therapy as “one of the most outstanding current advances in the area of psychotherapy of alcoholism” and called for controlled studies to test the effectiveness of promising family-based interventions (Keller, 1974). Many investigative teams answered the call, initially with small-scale studies and, as evidence of effectiveness accumulated, by means of large-scale, randomized clinical trials. Their results confirmed the early promise of marital and family therapy. Meta-analytic reviews of randomized clinical trials have concluded that, in comparison to interventions that focus exclusively on the substance-abusing patient, both alcoholism and drug abuse treatments that involve family result in higher levels of abstinence (see, for example, Stanton and Shadish, 1997).

Three theoretical perspectives have come to dominate family-based conceptualizations of substance abuse and thus provide the foundation for the treatment strategies most often used with substance abusers. (aFor a review of these approaches, see Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, and Birchler, 2003a.)

The family disease approach, the best known model, views alcoholism and other drug abuse as illnesses of the family, suffered not only by the substance abuser, but also by family members, who are seen as codependent. Treatment consists of encouraging the substance-abusing patient and family members to address their respective disease processes individually; formal family treatment is not the emphasis.

The family systems approach, the second widely used model, applies the principles of general systems theory to families, paying particular attention to the ways in which family interactions become organized around alcohol or drug use and maintain a dynamic balance between substance use and family functioning. Family therapy based on this model seeks to understand the role of substance use in the functioning of the family system, with the goal of modifying family dynamics and interactions to eliminate the family’s need for the substance-abusing patient to drink or use drugs.

A third set of models, a cluster of behavioral approaches, assumes that family interactions reinforce alcohol-and drug-using behavior. Therapy attempts to break this deleterious reinforcement and instead foster behaviors conducive to abstinence.

Derived from this general behavioral conceptualization of substance abuse, behavioral couples therapy (BCT) is the approach to couples and family therapy that has, by our analysis, the strongest empirical support for its effectiveness (O’Farrell and Fals-Stewart, 2003). It is demonstrating success in broadly diverse populations, from very poor to wealthy, and among a broad range of ethnic and racial groups. This review provides brief discussions of the theoretical rationale for the use of BCT with substance-abusing patients, including:

BCT methods typically used with substance-abusing patients and their partners;

Research findings supporting the effectiveness of BCT in terms of its primary outcome goals (reduction or elimination of substance use and improvement in couples’ adjustment); and

Recently completed investigations that have shown positive effects of BCT on domains of functioning not specifically targeted by the intervention, such as reduced intimate partner violence and improved emotional and behavioral functioning on the part of children in the family.

THEORETICAL RATIONALE

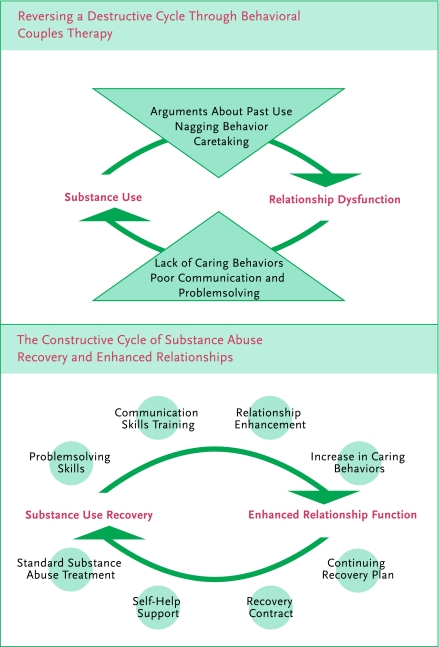

The causal connections between substance use and relationship discord are complex and reciprocal. Couples in which one partner abuses drugs or alcohol usually also have extensive relationship problems, often with high levels of relationship dissatisfaction, instability (for example, situations where one or both partners are taking significant steps toward separation or divorce), and verbal and physical aggression (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, and O’Farrell, 1999). Relationship dysfunction in turn is associated with increased problematic substance use and posttreatment relapse among alcoholics and drug abusers (Maisto et al., 1988). Thus, as shown in the “destructive cycle” segment of the figure, “Reversing a Destructive Cycle Through Behavioral Couples Therapy,” substance use and marital problems generate a destructive cycle in which each induces the other.

In the perpetuation of this cycle, marital and family problems (for example, poor communication and problemsolving, habitual arguing, and financial stressors) often set the stage for excessive drinking or drug use. There are many ways in which family responses to the substance abuse may then inadvertently promote subsequent abuse. In many instances, for example, substance abuse serves relationship needs (at least in the short term), as when it facilitates the expression of emotion and affection through caretaking of a partner suffering from a hangover.

Recognizing these interrelationships, BCT and family-based treatments for substance abuse in general have three primary objectives:

To eliminate abusive drinking and drug abuse;

To engage the family’s support for the patient’s efforts to change; and

To restructure couple and family interaction patterns in ways conducive to long-term, stable abstinence.

As depicted in the “constructive cycle” segment of the figure, BCT attempts to create a constructive cycle between substance use recovery and improved relationship functioning through interventions that address both sets of issues concurrently.

Reversing a Destructive Cycle Through Behavioral Couples Therapy

BCT METHODS

BCT can be conducted in several formats and delivered either as a standalone intervention or as an adjunct to individual substance abuse counseling. In standard BCT, the therapist sees the substance-abusing patient and his or her partner together, typically for 15 to 20 outpatient couple sessions over 5 to 6 months. However, under some circumstances, therapists may administer group behavioral couples therapy (GBCT), treating three or four couples together, usually over 9 to 12 weeks. If necessary, a course of brief behavioral couples therapy can be accomplished in six sessions.

Appropriate Candidates for BCT

Because BCT relies on harnessing the influence of the couples system to promote abstinence, it is suitable only for couples who are committed to their relationships. We generally require that partners be married or, if unmarried, cohabiting in a stable relationship for at least 1 year; if separated, attempting to reconcile. In addition, BCT, like other behavioral treatments, is skill-based and relies heavily on participants’ abilities to receive and integrate new information, complete assignments, and practice new skills. Thus, both partners must be free of conditions such as gross cognitive impairment or psychosis that would interfere with the accomplishment of these tasks.

The BCT model assumes that both partners have abstinence from drugs or alcohol as their primary goal. BCT is therefore most effective when only one partner has a problem with drugs or alcohol. Relationships in which both partners abuse drugs often do not support abstinence and may be antagonistic to cessation of drug abuse. Compared to couples in which only one partner abuses drugs, “dually addicted” couples often report more relationship satisfaction, particularly when the partners use drugs together (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, and O’Farrell, 1999). They apparently have less conflict related to substance abuse, and attempting to reduce their substance abuse may reduce their relationship satisfaction by depriving them of a primary shared rewarding activity. Attempting to address the substance abuse of only one partner in a dually addicted couple—the most common circumstance, since both partners rarely seek help at the same time—often creates conflict that may be resolved only through either dissolution of the relationship or continued drug use by the partner being treated.

Couples are also excluded from participation in BCT if there is evidence that the relationship is significantly destructive or harmful to one or both partners. In particular, BCT is contraindicated for couples with histories of severe physical aggression. For example, couples are not appropriate candidates if they report violence within the last year that necessitated medical attention or if either partner describes being physically afraid of the other. Such partners are referred for domestic violence treatment, and the substance-abusing partner receives counseling for his or her drinking or drug abuse.

Exclusion rates vary according to gender. The man is much more frequently the sole substance abuser in a couple, and consequently women are much more frequently excluded on the basis of being in a dually addicted pair. In fact, as many as 50 percent of women entering treatment may be excluded from standard BCT on these grounds. Alternative programs for these women are under development.

Among individuals entering outpatient treatment who are offered BCT, roughly 80 percent choose to participate.

General Session Content and Procedures

The BCT approach has been fully manualized, with manuals and related materials readily available to researchers and practitioners.1 During initial BCT sessions, therapists work to decrease the couple’s negative feelings and interactions about past and possible future drinking or drug use, and to encourage positive behavioral exchanges between the partners. Later sessions move to engage the partners in communication skills training, problemsolving strategies, and negotiation of behavior change agreements.

At the outset of BCT, the therapist and the couple together develop a recovery contract. As part of the contract, the partners agree to engage in a daily abstinence trust discussion (or sobriety trust discussion). In this brief exchange, the substance-abusing partner typically says something like, “I have not used drugs in the last 24 hours and I intend to remain abstinent for the next 24 hours.” In turn, the non-substance-abusing partner expresses support by responding, for example, “Thank you for not drinking or using drugs during the last day. I want to provide you the support you need to meet your goal of remaining abstinent today.”

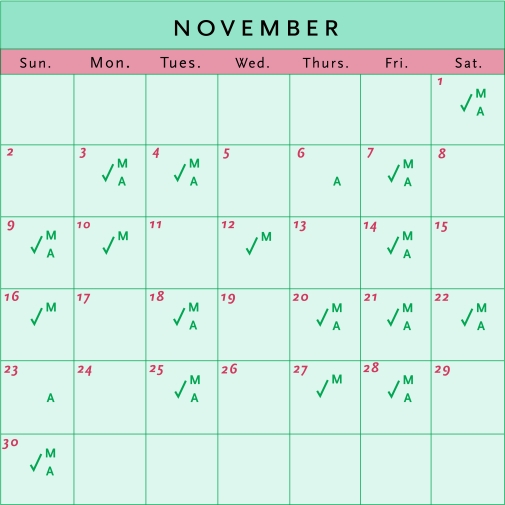

For patients taking medications such as naltrexone or disulfiram to facilitate abstinence, ingestion of each day’s dose can be a component of the abstinence trust discussion, with the non-substance-abusing partner witnessing and providing verbal reinforcement. The non-substance-abusing partner records the performance of the abstinence trust discussion and other activities in the recovery contract (for example, attendance at self-help support groups) on a calendar provided by the therapist. The calendar is an ongoing record of progress that the therapist can praise in BCT sessions, as well as a visual and temporal record of problems with adherence. (See “Sample Calendar for Recording Recovery Contract Activities.”) During each BCT session, the partners perform behaviors stipulated in their recovery contract, such as their abstinence trust interaction, which highlights the behaviors’ importance and enables the therapist to observe and provide affirming or corrective feedback.

Sample Calendar for Recording Recovery Contract Activities.

M = consumption of abstinence-supporting medication

A = attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meeting

✓= completion of abstinence trust discussion

BCT sessions tend to be moderately to highly structured, with the therapist setting a specific agenda at the start of each meeting. Typically, the therapist begins by asking about urges to break abstinence since the last session and whether any drinking or drug use has occurred. The therapist and the partners review compliance with agreed-upon activities since the last session and discuss any difficulties the couple may have experienced.

The session then moves to a detailed review of homework and the partners’ successes and problems in completing their assignments. The partners report any relationship or other problems that may have arisen during the last week, with the goal of resolving them or designing a plan to resolve them. The therapist then introduces new material, such as instruction in and rehearsal of skills to be practiced at home during the ensuing week. Toward the end of the session, partners receive new homework assignments to complete before the next session.

BCT also employs a set of behavioral assignments designed to increase positive feelings, shared activities, and constructive communication, all of which are viewed as conducive to abstinence (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, and Birchler, 2003b):

When Progress in Behavioral Couples Therapy Is Insufficient: How the Therapist Responds

| Problem | Criterion | Therapist’s Response |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship distress | Either partner, 3 weeks in a row, reports clinically significant relationship distress. | Focus on relationship enhancement and communications skills training. |

| Continued or renewed substance use | The substance-abusing partner reports substance use 2 weeks in a row or urges to use 3 weeks in a row. | Place greater emphasis on substance use issues. Encourage attendance at self-help meetings and more frequent contact with the individual counselor. Identify and reduce the stressors under- lying or contributing to cravings. |

| Noncompliance with homework | The couple fails to complete homework 2 weeks in a row. | Isolate and eliminate factors interfering with completion. Reduce the amount of homework to a level manageable by both partners. |

| Arguments about past substance abuse | Either partner reports such arguments 2 weeks in a row. This violates one of the major tenets of the intervention, which focuses on the future, not the past. | Encourage the non-substance-abusing partner to discuss these issues in Al- Anon meetings or with an individual counselor. |

| Angry touching | There have been episodes of mild physical aggression between partners. | Reiterate the couple’s commitment not to resolve conflict with physical aggression of any kind; emphasize conflict resolution skills. Severe violence (e.g., behavior causing injury or fear) is another matter. Refer partner to domestic violence treatment and cease BCT. |

In the “Catch Your Partner Doing Something Nice” exercise, each partner notices and acknowledges one pleasing behavior that the significant other performs each day.

In the “Caring Day” assignment, each partner plans ahead to surprise the other with a day when he or she does some special things to show caring.

Planning and engaging in mutually agreed-upon shared rewarding activities are important; many substance abusers’ families have lost the custom of doing things together for pleasure, and regaining it is associated with positive recovery outcomes.

Practicing communication skills—paraphrasing, empathizing, and validating—can help the substance-abusing patient and his or her partner better address stressors in their relationship and their lives. These skills are also believed to reduce the risk of relapse to substance abuse.

As a condition of the recovery contract, both partners agree not to discuss past drinking or drug abuse, or fears of future substance abuse, between scheduled BCT sessions. This agreement reduces the likelihood of substance-abuse-related conflicts occurring outside the therapy sessions, where they are more likely to trigger relapses. Partners are asked to reserve such discussions for the BCT sessions, where the therapist can monitor and facilitate the interaction.

Throughout BCT, the therapist monitors both partners’ relationship satisfaction. In each session, the partners complete two brief measures: the Marital Happiness Scale (Azrin, Naster, and Jones, 1973), which assesses relationship adjustment for the previous week, and the Response to Conflict Scale (Birchler and Fals-Stewart, 1994), which evaluates the partners’ use of maladaptive methods such as yelling, sulking, or hitting to handle relationship conflict during the last week.

If the partners are not making sufficient progress in any areas, the therapist gives greater attention to skills that address the specific problems. For example, if the patient is not abusing or reporting urges to abuse drugs or alcohol, but the partners report that their relationship conflict and distress are not abating, the therapist stresses relationship enhancement exercises and communication skills (see “When Progress in Behavioral Couples Therapy Is Insufficient: How the Therapist Responds”).

Coordination With Other Therapy Components

If, as typically happens, BCT is provided in conjunction with individual substance abuse counseling, the respective treatment providers share information about the patient’s progress. Such coordination is essential to maximize the effectiveness of both modalities, as patients often disclose problems in one type of counseling that are best addressed in the other treatment format. For instance, a couple might discuss in a BCT session the patient’s need for vocational training to obtain a higher paying job, but the individual treatment provider is usually better positioned to coordinate such training as part of the patient’s overall treatment plan.

Planning for Continuing Recovery

Once the couple has attained stability in abstinence and relationship adjustment, the partners and the therapist begin discussing plans for maintaining therapy gains after formal BCT is completed. From a couples therapy perspective, relapses can take the form of a return to substance use or a recurrence of relationship difficulties. Consistent with Marlatt and Gordon’s (1985) seminal work on relapse prevention, the therapist discusses openly with both partners the fact that relapse is a common, though not inevitable, part of the recovery process. The therapist also emphasizes that relapse does not indicate that the treatment has failed and encourages the couple to make plans to handle such occurrences.

There is a strong tendency for the non-substance-abusing member of the couple to see any relapse to substance abuse by his or her partner as a betrayal of the relationship, a failure of the treatment, and an indication that their problems are never going to end. To counter this response, the discussion and planning for relapse include encouragement for both partners to view relapse, if it should occur, as a learning experience and not a reason to abandon hope and commitment.

In the final BCT sessions, the couple writes a continuing recovery plan. The plan provides an overview of the couple’s ongoing post-BCT activities to promote stable abstinence (for example, a continuing daily abstinence trust discussion and attendance at self-help support meetings), relapse contingency plans (such as recontacting the therapist, re-engaging in self-help support meetings, contacting a sponsor), and activities to maintain the quality of their relationship (for example, by continuing to schedule shared rewarding activities).

The Appropriate Therapeutic Stance

The therapist’s ability to develop a strong collaborative therapeutic alliance with the partners is essential for successful BCT. Key therapeutic skills include empathizing, instilling a sense of hope, and working on mutually established goals. The most common clinical barrier to engaging and allying with couples in treatment is partners’ fears that sessions will become a forum for laying blame on each other. To allay such fears, the therapist should highlight skill-building goals and focus consistently on the present and future rather than the processing of emotional reactions to past problems. Most partners who participate in BCT report that the highly structured sessions and activity-based homework exercises are a welcome change from their otherwise chaotic lifestyles.

Although most couples who participate in BCT comply with session exercises and between-session homework assignments, some do not. When partners have difficulty completing assignments as agreed, the therapist assesses possible barriers and solicits the couple’s ideas for enhancing compliance. In addition, the therapist can adjust assignments that may be too ambitious for some partners, for example, by reducing the weekly quota of self-help meetings. The therapist can also conduct brief telephone conferences with the partners between sessions to assess their progress on the week’s assignments and encourage completion of the homework.

However, noncompliance with agreed-upon assignments is never excused or ignored in BCT. A pattern of avoidance and failure to follow through on commitments is often characteristic of these couples. Allowing the partners to break commitments in therapy is likely to undermine the goals of the intervention by perpetuating and reinforcing behaviors that may underlie many of the couples’ problems.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Investigations over 30 years have compared drinking and relationship outcomes obtained with BCT to the results of various non-family-focused interventions, such as individual counseling sessions and group therapy. The earlier studies measured outcomes at 6 months after treatment, the more recent investigations at 18 to 24 months. Despite variations in methods of assessment, in certain aspects of BCT, and in the types of individual-based treatments used for comparison, the results have consistently indicated less frequent drinking, fewer alcohol-related problems, happier relationships, and lower risk of marital separation with BCT (McCrady et al., 1991).

Research on the effects of BCT for patients who abuse drugs other than alcohol got under way much later but has already shown substantial positive results. The first randomized study compared BCT plus individual treatment to equally intensive individual treatment (the same number of therapy sessions during the same time period) for married or cohabiting male patients entering an outpatient substance abuse treatment program (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, and O’Farrell, 1996). The individual-based treatment (IBT) method used in this study was a cognitive-behavioral coping skills intervention designed to teach patients how to recognize relapse triggers, how to deal with urges to use drugs, and related skills.

About 50 percent of the men who received BCT during the study remained abstinent from alcohol and other drugs, compared to 30 percent of the IBT group. During the year after treatment, fewer members of the group who received BCT had drug-related arrests (8 percent v. 28 percent) and inpatient treatment episodes (13 percent v. 35 percent) than the comparison group; and BCT recipients maintained a larger percentage of abstinent days (67 percent v. 45 percent) than the IBT group. Couples who received BCT also reported more positive relationship adjustment and fewer days of separation caused by discord than couples in which the male partner received only individual treatment. Similar results favoring BCT over individual counseling were observed in another randomized clinical trial that involved married or cohabiting male patients in a methadone maintenance program (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, and Birchler, 2001a).

Fals-Stewart and O’Farrell (2003) completed a study of behavioral family contracting (BFC)-plus-naltrexone therapy for male opioid-dependent patients. The BFC intervention, a variant of BCT that allows for the inclusion of family members other than spouses, focuses primarily on establishing and monitoring a recovery contract between the participants, with less attention to other prominent aspects of standard BCT such as communication training and relationship enhancement exercises. In our BFC study, 124 out-patient men who were living with a family member (66 percent with spouses, 25 percent with parents, and 9 percent with siblings) were randomly assigned to one of two equally intensive 24-week treatments:

BFC plus individual treatment. Patients had both individual and family sessions and took naltrexone daily in the presence of a family member as part of the recovery contract.

Individual-based treatment only. Patients were prescribed naltrexone and were asked in counseling sessions about their compliance, but there was no family involvement or compliance contract.

In the course of this study, BFC patients ingested more doses of naltrexone than their IBT-only counterparts, attended more scheduled treatment sessions, remained continuously abstinent longer, and had significantly more days abstinent from opiate-based and other illicit drugs during treatment and in the year after treatment. BFC patients also had significantly fewer drug-related, legal, and family problems at 1-year followup.

Winters and colleagues (2002) conducted the first BCT study that focused exclusively on female drug-abusing patients. Seventy-five married or cohabiting women with a primary diagnosis of drug abuse (52 percent cocaine, 28 percent opiate, 8 percent cannabis, and 12 percent other drugs) were randomly assigned to one of two equally intensive outpatient treatments:

BCT plus individual-based treatment (a cognitive-behavioral coping skills program); or

IBT alone.

During the 1-year posttreatment followup, women who received BCT had significantly fewer days of substance use, longer periods of continuous abstinence, and higher levels of relationship satisfaction than did participants who received individual treatment. The findings were very similar to those obtained in BCT studies with male substance-abusing patients.

In all these studies, the effects of BCT on substance use reduction and relationship enhancement are moderate to large, according to Cohen’s (1988) conventions; however, BCT’s effects tend to decline over time once treatment has ended. This is not unexpected, as decay of effects occurs after most psychosocial treatments for substance abuse. It does indicate, however, that for BCT as well as those other interventions, more emphasis on methods to enhance the durability of benefits is needed. In a study of couples with an alcoholic male partner, we found that additional relapse prevention sessions with the couples after the completion of primary treatment helped them sustain therapy gains (O’Farrell et al., 1993).

Dually Addicted Couples

When both partners in a relationship use drugs, neither traditional individual therapy nor BCT has proven effective. Research on the dynamics of these relationships is needed, as is research on interventions that might work. A study now in its early stages is examining the use of a combination of BCT and contingency management techniques. The contingency management component offers material incentives, such as vouchers that can be exchanged for goods and services unrelated to substance use, provided the partners produce drug-negative urine samples and attend BCT sessions together. Although preliminary results are encouraging, far more data are needed to ascertain the long-term effectiveness of this approach with dually addicted couples.

Effects on Secondary Outcome Domains

In the 1990s, investigators turned their attention to outcomes that are not specifically targeted by BCT but might reasonably be expected to improve when BCT reduces drinking and enhances couples’ relationships. In particular, they have examined BCT’s effects on intimate partner violence (IPV), and on the emotional and behavioral adjustment of children living in homes with a substance-abusing parent.

Patrick Zachmann, 1978 / Copyright 2002, Magnum Photos

Intimate partner violence

IPV is highly prevalent among substance-abusing patients and their partners. For example, recent studies among married or cohabiting men entering treatment for alcoholism have shown that:

Two-thirds of the men or their partners report at least one episode of male-to-female physical aggression in the preceding year, four times the IPV prevalence estimated from nationally representative surveys (O’Farrell et al., 2003); and

Male-to-female physical aggression was nearly eight times as likely on days of drinking as on days of no drinking (Fals-Stewart, 2003) and roughly three times as high on days of cocaine use as on days of no substance use (Fals-Stewart, Golden, and Schumacher, 2003).

In a recent study, O’Farrell and colleagues (in press) examined partner violence before and after BCT among 303 married or cohabiting male alcoholic patients, using a demographically matched comparison group of nonalcoholic men. In the year before BCT, 60 percent of the alcoholic patients had been violent toward their female partners, five times the 12-percent rate for the comparison group. In the year after BCT, the rate of violence decreased to 24 percent in the total alcoholic group and to 12 percent—identical to the comparison group—among those who achieved and sustained remission. Results for the second year after BCT were similar. Attending more scheduled BCT sessions and using BCT-promoted behaviors more often during and after treatment were related to less drinking and less violence after BCT, suggesting that the skills couples learn in BCT may both promote abstinence and reduce violence.

Fals-Stewart and colleagues (2002) examined changes in IPV among 80 married or cohabiting drug-abusing men and their partners when the men were randomly assigned to receive either BCT or an equally intensive individual treatment. Nearly half the couples in each group reported male-to-female physical aggression during the year before treatment; in the year following treatment, that number fell to 17 percent for the BCT group and 42 percent for those in individual treatment. The greater reduction in violence with BCT appeared to be a consequence of BCT’s greater impact on drug use, drinking, and relationship problems.

Children’s emotional, behavioral adjustment

Children of alcoholics (COAs) are more likely than other children to have psychosocial problems. For example, they experience more somatic complaints, internalizing behavior problems (such as anxiety and depression), and externalizing behavior problems (such as conduct disorder and alcohol use); lower academic achievement; and lower verbal ability.

Research on children of drug-abusing parents is far less evolved than the COA literature (a database of which can be found at www.nacoa.org), but results so far suggest that they, too, have significant emotional and behavioral problems. Preliminary studies indicate that their psychosocial functioning may in fact be significantly worse than that of demographically matched COAs (Fals-Stewart et al., in press).

Despite the emotional and behavioral problems observed among COAs, surveys of custodial parents entering substance abuse treatment suggest that they are reluctant to allow their children to engage in any type of mental health treatment (Fals-Stewart, Fincham, and Kelley, in press). Thus, the most readily available approach to improving these children’s psychosocial functioning may be to treat their parents, with the hope that outcomes such as reduced substance use, improved communication, and reduced conflict might indirectly benefit their children.

Kelley and Fals-Stewart (2002) have reported two completed investigations with married or cohabiting male patients who had one or more school-aged children residing in their homes: one with 64 alcoholic men and one with 71 drug-dependent men. In each study, the men were randomly assigned to one of three equally intensive outpatient treatments: BCT, IBT, or couples-based psychoeducational attention control treatment (PACT). The last of these consists of lectures to both partners on various topics related to drug abuse, including its etiology and epidemiology and the effects of drugs on the brain and other parts of the body. In the year after treatment, BCT produced a greater reduction of substance use for the men in these couples and more gains in relationship adjustment than did IBT or PACT. Children of fathers in all three treatment groups showed improved functioning, but children of fathers who participated in BCT improved more than did children in the other groups, as indicated by Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) scores (the checklist is discussed in Jellinek and Murphy, 1990). Moreover, the proportion of children whose PSC scores indicated clinically significant impairment was lowered only for those children whose parents participated in BCT. The BCT intervention contained no session content focusing directly on parenting practices or problems with child-rearing, yet its positive effects for the couple appeared to help the couple’s children, too.

BARRIERS TO DISSEMINATION OF BCT

Although strong research supports BCT’s efficacy, the intervention is not now widely used in community-based treatment. Fals-Stewart and Birchler (2001) surveyed program administrators in 398 randomly selected U.S. substance abuse programs and found that 27 percent provided some type of service that included couples, but mostly limited to assessment. Fewer than 5 percent used behavior-oriented couples therapy, and none used BCT specifically.

In the same survey, program administrators responded to queries about barriers to BCT adoption. They raised two primary concerns: that the number of sessions required for BCT made the intervention too costly; and that their counselors had less formal education or clinical training than the master’s-level therapists who administered BCT in most studies, and so might not be able to deliver the intervention as effectively.

A series of recently completed studies addressed these concerns. Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, and Birchler (2001b) evaluated a brief version of BCT. Eighty couples were randomly assigned for a 12-week period to one of four interventions:

Brief BCT with 12 sessions—6 couples sessions alternating with 6 individual sessions;

Standard BCT with 24 sessions—12 BCT sessions alternating with 12 individual counseling sessions;

Individual treatment, with 12 individual sessions; or

PACT with 12 sessions—6 individual sessions alternating with 6 educational sessions for the couple.

Brief BCT and standard BCT were significantly more effective than IBT or PACT in terms of male partners’ percentage of days abstinent and several other outcome indicators during the year after treatment. Furthermore, brief BCT and standard BCT produced equivalent outcomes at 1-year followup.

Subsequently, with 75 drug-abusing men and their wives or cohabiting partners, Fals-Stewart, Birchler, and O’Farrell (2002) compared the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of three treatment formats:

Twelve sessions of standard BCT, delivered to the partners in a couples therapy format, plus 12 sessions of group drug counseling (GDC) featuring session material on 12-step facilitation;

A 12-session group BCT (GBCT), delivered to multiple couples in a group therapy format, plus 12 sessions of GDC; and

A 24-session GDC for the male partners only.

Compared to participants assigned to GDC, participants in BCT and GBCT had significantly better substance use and relationship outcomes during a 12-month posttreatment followup period; the differences between BCT and GBCT were not significant.

The investigators calculated the agency’s per patient cost for each of the three interventions, including treatment providers’ salaries, facility rentals, agency overhead costs, and so forth, and analyzed cost-effectiveness. Because the GBCT participants attained clinical outcomes similar to those who received BCT, but at a lower treatment delivery cost ($1,428 v. $2,091 per patient), GBCT was significantly more cost-effective than standard BCT. GBCT was more costly than GDC ($1,290 per patient), but it also was more cost-effective in light of GBCT participants’ superior outcomes. These findings complement the results of an earlier study indicating that BCT was more cost-effective than an equally intensive individual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, and Birchler, 1997).

Fals-Stewart and Birchler (2002) examined the impact of the counselor’s educational background on BCT, comparing outcomes for 48 alcoholic men and their female partners who were randomly assigned to BCT with either a bachelor’s-level or master’s-level counselor. The bachelor’s-level counselors performed as well as the master’s-level counselors in terms of adherence to a BCT manual. An experienced BCT therapist who reviewed audiotaped and videotaped sessions, unaware of the counselors’ educational backgrounds, rated the bachelor’s-level counselors slightly lower on quality of treatment delivery; however, treatment quality was rated in the excellent range for both groups of counselors.

Couples who received BCT from the bachelor’slevel or the master’s-level counselors reported equivalent levels of:

Satisfaction with treatment,

Relationship happiness during treatment,

Relationship adjustment, and

Percentage of the alcoholic patient’s abstinence days at 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month followup.

In addition, the bachelor’s-level counselors reported that BCT was very easy to learn and that the structured therapy format provided a very clear set of guidelines for working with couples—a generally unfamiliar clinical subpopulation for these counselors.

In summary, studies have not borne out program administrators’ primary concerns about implementing BCT. Clinical effectiveness of BCT did not vary with the counselors’ educational backgrounds, and concerns about the number of BCT sessions required could be alleviated through use of an abbreviated version of BCT or BCT delivered in a group therapy format. The findings suggest that community-based substance abuse treatment programs can provide BCT effectively.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A large and growing body of research on BCT indicates that this intervention produces significant reductions in substance abuse, improves relationship satisfaction, and also has very important secondary effects, including reductions in partner violence and improvements in children’s psychosocial adjustment. Given the significant benefits to individuals and their families who participate in BCT, researchers need to redouble their efforts to disseminate these techniques to community-based providers of substance abuse services. Adding BCT to the treatment toolbox of these professionals will make the intervention available to more families who are very likely to benefit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIDA grants R01-DA-01-2189, R01-DA-01-4402, R01-DA-01-5937, and R01-DA-01-6236; NIAAA grants K02-AA-01-0234 and R21-AA-01-3690; and the Alpha Foundation.

Footnotes

Readers can obtain the BCT manuals for free by downloading from www.addictionandfamily.org or by e-mailing a request to devans@addictionandfamily.org.

REFERENCES

- Azrin NH, Naster BJ, Jones R. Reciprocity counseling: A rapid learning-based procedure for marital counseling. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1973;11(4):365–382. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler GR, Fals-Stewart W. The Response to Conflict Scale: Psychometric properties. Assessment. 1994;1(4):335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2d ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of interpartner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR. A national survey of the use of couples therapy in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00165-9. discussion 285–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholic men and their intimate partners: The comparative effectiveness of bachelor’s- and master’s-level counselors. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33(1):123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral couples therapy for male substance-abusing patients: Effects on relationship adjustment and drug-using behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):959–972. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O’Farrell TJ. Drug-abusing patients and their intimate partners: Dyadic adjustment, relationship stability, and substance use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(1):11–23. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral couples therapy for drug-abusing men and their intimate partners: Group therapy versus conjoint therapy formats. In: Atkins DC, editor. Affairs, Abuse, Drugs, and Depression: The Promises and Pitfalls of Couples Therapy. Symposium conducted at the 36th Annual Convention of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Reno, NV. November 14–17.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Fincham F, Kelley M. Brief report: Substance-abusing parents’ attitudes toward allowing their custodial children to participate in treatment: A comparison of mothers versus fathers. Journal of Family Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.666. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Golden J, Schumacher J. Intimate partner violence and substance use: A longitudinal day-to-day examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(9):1555–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral family counseling and naltrexone compliance for male opioid-dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):432–442. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for male substance-abusing patients: A cost-outcomes analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(5):789–802. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for male methadone maintenance patients: Effects on drug-using behavior and relationship adjustment. Behavior Therapy. 2001a;32(2):391–411. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Both brief and extended behavioral couples therapy produce better outcomes than individual treatment for alcoholic patients. In: O’Farrell TJ, editor. Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcohol and Drug Problems: Recent Advances. Symposium conducted at the 24th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Montreal, Canada. June 2001.2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Family therapy techniques. In: Rodgers F, Morgenstern J, Walters ST, editors. Treating Substance Abuse: Theory and Technique. 2d ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2003a. pp. 140–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Mechanisms of action. Paper presented at the 37th annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Boston. November 2003.2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, et al. Behavioral couples therapy for drug-abusing patients: Effects on partner violence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, et al. The emotional and behavioral problems of children living with drug-abusing fathers: Comparisons with children living with alcohol-abusing and non-substance-abusing fathers. Journal of Family Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.319. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek MS, Murphy JM. The recognition of psychosocial disorders in pediatric office practice: The current status of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1990;11:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, editor. Second Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1974. Trends in treatment of alcoholism; pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Fals-Stewart W. Couples- versus individual-based therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Effects on children’s psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):417–427. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, et al. Alcoholics’ attributions of factors affecting their relapse to drinking and reasons for terminating relapse episodes. Addictive Behaviors. 1988;13(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady B, et al. Effectiveness of three types of spouse-involved alcoholism treatment. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(11):1415–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W. Alcohol abuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29(1):121–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, et al. Behavioral marital therapy with and without additional couples relapse prevention sessions for alcoholics and their wives. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54(6):652–666. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, et al. Partner violence before and after individually based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):92–102. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, et al. Domestic violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment: The role of treatment involvement and abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family-couples treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122(2):170–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters J, et al. Behavioral couples therapy for female substance-abusing patients: Effects on substance use and relationship adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):344–355. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]