Abstract

Maryhaven, a comprehensive, community-based drug abuse treatment facility, combines a core commitment to 12-step principles and practices with the use of scientifically derived treatment interventions. Treatment goals at Maryhaven include abstinence from substance abuse, patient engagement and progress in 12-step activities, and strong patient affiliation with 12-step organizations within the community. The author discusses the reasons why Maryhaven takes this approach, describes the program’s use of empirically derived treatment tools to further 12-step objectives, argues that there are natural affinities between 12-step and some empirical treatment tools such as the Stages of Change model, and suggests research projects that he believes can improve treatment and illuminate the mechanisms by which 12-step activities help patients overcome addiction.

Historically, the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other 12-step organizations have been an integral part of the development of drug abuse treatment. Substance abuse treatments utilizing a 12-step approach evolved to meet the needs of patients who are not successful at establishing recovery solely through 12-step organizations. Over time, the sophistication and comprehensiveness of treatments have increased with developments in medication and behavioral therapies and with a more complex view of the barriers to establishing and maintaining recovery. Today, there is considerable diversity among treatment programs using a 12-step-related approach. This article presents the author’s views on 12-step participation as a pathway to recovery, based on his work experience at one such program.

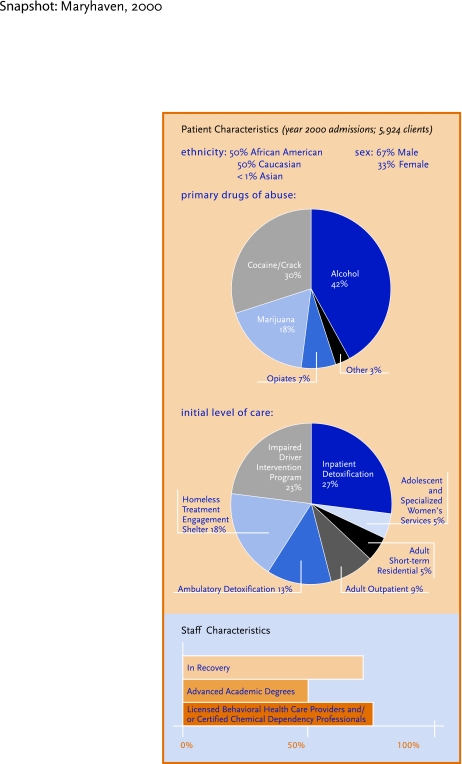

Maryhaven, Central Ohio’s oldest and largest substance abuse treatment facility, admits more than 6,000 inpatients and outpatients annually to a continuum of abstinence-based treatments ranging from homeless shelter engagement centers to long-term residential services (see “SNAPSHOT: Maryhaven, 2000”). In combining components of 12-step and empirically based interventions, Maryhaven probably resembles a majority of the substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. For example, as many as 95 percent of inpatient alcohol treatment programs have reported the use of a 12-step approach (Brown et al., 1988). A survey of drug treatment programs in Los Angeles County estimated that 75 percent placed some emphasis on the 12 Steps (Polinsky et al., 1995). Acceptance of the 12-step approach is so widespread that Room and Greenfield (1993) found, using data from the 1990 U.S. National Alcohol Survey, that 13.3 percent of the U.S. adult population reported having attended at least one 12-step meeting.

Throughout Maryhaven’s history, since its founding in 1960 as a home for women with alcoholism, recovering individuals and those highly dedicated to the use of a 12-step recovery approach have been well represented in all aspects of the organization. An estimated 73 percent of the treatment staff are recovering, a majority of whom credit 12-step organizations for their ability to maintain their recovery, and believe they have a responsibility to help drug-dependent patients establish 12-step recovery. Commitment to the 12-step approach is equally strong among staff members who hold advanced degrees and those who do not. Among both groups, many are themselves recovering from addiction.

In its passionate and experiential, rather than science-based, commitment to 12-step programming, Maryhaven again is representative of many treatment programs. The 12-step approach has most often not been selected solely in the confines of rational deliberation; rather, it has been embraced with a fervor reflecting a closely held and cherished belief. While empirical support of the 12-step approach is mounting (Fiorentine and Hillhouse, 2000; Humphreys, 1999; Johnson and Chappel, 1994), that support has little to do with its broad acceptance by patients and providers. Instead, the greatest endorsement of this approach is the day-to-day reinforcing experience of providers witnessing the results of successful patient engagement in 12-step activities and organizations.

The recovering community represents a valuable and abundant pool of potential employees who have intimate familiarity with the principles of 12-step recovery and often some experience with treatment. At Maryhaven, entry-level personnel who are in recovery are supervised to help them separate their personal recovery issues from their professional roles, and they are expected to progress through training and certification programs for counseling and substance abuse treatment. This influx of recovering individuals continually renews the staff commitment to a 12-step-related treatment approach.

PROGRAMS, FELLOWSHIPS, AND ORGANIZATIONS

Alcoholics Anonymous, the original 12-step organization, was founded in 1935 to aid recovery from alcoholism. The acceptance of open discussion of drug abuse in AA meetings has grown, but still varies greatly from group to group. The guiding principle that seems to prevail in the Maryhaven community is reflected in the AA Preamble read at the opening of every meeting, which states simply, “The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc., 1986). Narcotics Anonymous (NA), an alternative 12-step organization for people addicted to drugs other than alcohol, is also a program of complete abstinence, including abstinence from alcohol.

In his review of AA’s history and development, Kurtz makes a helpful distinction between the “AA Program” and the “AA Fellowship” (Kurtz, 1979). The “Program” is described in the basic texts of AA—primarily the books Alcoholics Anonymous and Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. The program remains stable: Even when these principal texts are revised, great care is taken to maintain the original intent and, in most cases, the original language. The “Fellowship,” on the other hand, refers to the experience a person has when he or she attends AA meetings and becomes involved with its members. So 12-step fellowships can vary greatly.

Aspects of both the program and the fellowship are utilized widely in drug treatment. In this article, the term “12-step organization” refers to the 12-step self-help organizations such as AA, NA, and Cocaine Anonymous; the terms “fellowship” and “program” are as they have been defined by Kurtz.

TREATMENT OVERVIEW

The treatment offered at Maryhaven in the center’s early days most closely resembled the approach commonly known as the Minnesota Model (Cook, 1988). Over the years Maryhaven has enhanced and modified its approach so that today the range of services and resources resembles the description of “Components of Comprehensive Drug Abuse Treatment” in NIDA’s booklet Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1999). Depending on the level of care to which a patient is admitted, he or she has access to a wide range of biopsychosocial interventions. Trained Maryhaven staff members can provide patients with motivational interviewing, motivational incentives, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and use of buprenorphine in opiate detoxification.

Trends in biopsychosocial treatment, better trained staff, changes in patient presentation (such as changes in patterns of drug use and increased homelessness), and changes in public policy and funding have had a remarkable impact upon drug abuse treatment services. For example, while all of Maryhaven’s drug dependence treatment is abstinence-oriented, we frequently use medications for detoxification and for treating co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Nothing inherent in a 12-step approach precludes the use of medications such as Antabuse (disulfiram) and methadone for enhancing drug treatment, but they generally are not used. Both the cost of the medications and the need for continual medical supervision are prohibitive for the outpatient population. The use of medications is also limited by cost-benefit concerns, since Maryhaven’s interventions aim for total drug abstinence and many addiction medicines target only specific drugs.

Any practice or service that conflicts with a 12-step recovery approach is unlikely to be adopted at Maryhaven. For example, any treatment approach that seeks to moderate rather than eliminate the dependent patient’s use of alcohol or illicit drugs would be rejected outright.

Overall treatment goals at Maryhaven are to assist patients in establishing abstinence, affiliation with 12-step organizations, and stability or improvement in a full range of mind, body, and behavioral functions. Like other centers that provide treatment based on the 12 Steps, Maryhaven operates with these basic assumptions:

Alcohol and other drug (AOD) dependence is a chronic illness.

Abstinence from alcohol and illicit drug use is essential to establishing recovery from AOD dependence.

Involvement with 12-step organizations is the most readily available and, for most individuals, the best way to achieve and maintain recovery.

Immersion in the 12-step fellowships and program beginning in treatment is the best way to achieve 12-step organization affiliation after treatment.

Maryhaven uses a version of the American Society of Addiction Medicine Patient Placement Criteria, adapted by the Ohio Department of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Services, to determine when a patient meets the criteria for admission, continued stay, or discharge from each of the levels of care. Patients present with a diverse range of issues and situations that can affect the course of their individual treatments; however, some general observations are possible. During treatment all patients become knowledgeable about both the 12-step program and fellowships. All receive encouragement to begin attending 12-step meetings immediately. Those who have no 12-step program affiliation, or only a weak link to a group, are provided active referral services that include linking with 12-step group members and arranging temporary sponsors, transportation, and child care as needed. Most form or renew relationships with members of the 12-step organizations and begin working on the 12 Steps, intended as a process of spiritual awakening. Typically, patients complete the worksheet and treatment process for the first three Steps while they are in treatment (see “The First Three Steps”). Longer term programs assist the patient toward further progress in the Steps.

Maryhaven integrates 12-step-related practices and interventions into all its basic services to assist the patient with the goals of self-diagnosis, acceptance of addiction as an illness, acceptance of abstinence from AOD use as a necessary condition for recovery, and lasting affiliation with 12-step organizations. For example, individual treatment planning explicitly incorporates participation in 12-step-related activities, Step work, readings, and engagement with 12-step support people. Patients routinely receive advice on integrating interventions for other issues that affect their treatment plan—such as medical problems, physical injury, co-occurring mental disorders, behavioral problems, anger, social skills deficits, and housing and employment—into their 12-step recovery.

The First Three Steps.

Most Maryhaven patients complete the first three to five AA or NA Steps during their treatment. They use worksheets generated by the programs and tailored to each patient’s drug of choice and stage of treatment. In general, the worksheets follow the Steps as outlined in the basic Narcotics Anonymous text (NA World Services Office, 1988) and are very similar to the “Step Guides” published by Hazelden.

Step 1. “We admitted we were powerless over our addiction, that our lives had become unmanageable.” The patient’s work on this step usually involves writing a detailed description of his or her drug use, emphasizing negative consequences, failed attempts to control drug use, and the progression of symptoms and associated problems. Through this exercise patients gain insight about the severity of their problem and the numerous areas of their lives it has affected; and they begin to address the need for abstinence.

Patients present their work in a group counseling setting, telling their stories and receiving feedback from their peers and counselors. They usually have heard other group members present Step 1 work ahead of them, which helps enable them to achieve a high level of self-disclosure. The common ground of patients’ stories provides a normalizing and emotionally corrective quality to the experience. Group members provide considerable support and acceptance to each other in this process, which proves particularly helpful for patients who are still struggling with guilt and shame associated with harsh judgments of their own shortcomings. This is often the point at which patients experience a paradox: They begin to feel empowered through the acceptance of their powerlessness over addiction.

Step 2. “We came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” Worksheets and treatment processes related to Step 2 guide the patients to examine the role of pathological defenses and thinking errors in their beliefs and behavior. There is also an accompanying process of values clarification. Many patients are faced with clarifying religious beliefs and understanding concepts of spirituality. Some choose to suspend decisions about religious beliefs and simply use the 12-step fellowship itself as a “higher power” for purposes of their recovery. This step work is completed in group and/or individual counseling and frequently also involves spiritual counsel.

Step 3. “We made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.” In-treatment work on Step 3 generally helps patients look at their commitment to recovery and put plans into action to change their behavior. This step directly addresses patients’ setting aside egocentric self-will and accepting a spiritual or ethical foundation for their lives.

Because this Step makes explicit reference to God, atheists or agnostics may find it problematic. The book Alcoholics Anonymous states that nearly half the early members considered themselves atheists or agnostics and that whenever the text makes reference to God, it is referring to a “…Creative Intelligence, a Spirit of the Universe . . . ” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc., 1986). In practice we often hear patients who are working through difficulties in this area choose simply to interpret GOD as an acronym meaning Good Orderly Direction. This issue is often important to patients, but rarely is it a substantial barrier to 12-step recovery. This topic is also addressed in the AA text Came To Believe, a compilation of member contributions regarding their spiritual journal, which is intended as “. . . an outlet for the rich diversity of convictions implied in ‘God as we understood Him’” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. 1983).

Group counseling sessions commonly incorporate 12-step principles, and some groups specifically focus on 12-step activities such as presenting and processing patients’ work on Step worksheets. (Groups that are not specifically intended to focus on the 12 Steps generally follow the group psychotherapy approach described by Yalom [1995].) Individual counseling, which is used primarily as an adjunct to group counseling and to coordinate case management needs, includes a focus on progress on 12-step worksheets, acceptance of the 12-step principles, and application of “recovery tools” to the patient’s personal situation. For example, patients who become easily discouraged or anxious about the many issues they are facing might be coached to reframe these problems into manageable tasks by learning to apply the slogan “one day at a time” to their situation.

Maryhaven hosts 7 weekly 12-step meetings at the facility. The Maryhaven staff monitors patients’ attendance at these meetings, and patients obtain feedback on their behavior and coaching to help them develop appropriate behaviors. Volunteers from the local recovering community provide fellowship, education, temporary sponsorship, and support. Lectures, discussions, films, and readings include 12-step topics such as sponsorship, the 12 traditions, and spiritual dimensions of recovery.

Patients who have completed a successful course of treatment generally have developed a realistic plan for recovery. Increased self-efficacy is evident in their confidence that they have the tools to maintain recovery. They have begun to develop a new support network and demonstrate a marked improvement in affect, cognition, and behavior. Maryhaven monitors program retention and dropout rates, treatment completion, and the Addiction Severity Index at admission and 30 days and 6 months posttreatment.

12-STEP ACTIVITIES, PROCESSES OF CHANGE

Maryhaven has adopted the Transtheoretical Model described by Prochaska and Norcross (1994), which is becoming increasingly familiar to drug treatment providers as a model for understanding change in relation to addiction and other problems. The Processes of Change in this model provide a useful scheme for understanding the relationship between change processes common in behavioral therapies and the 12-step-specific activities and materials used in drug treatment programs (see “12-Step Activities Linked to Processes of Change”). Processes of Change are “…the covert and overt activities that people engage in to alter affect, thinking, behavior, or relationships related to particular problems or patterns of living” (Prochaska and Norcross, 1994). The broad range of change processes suggests the usefulness of selective application of behavioral techniques and 12-step activities with patients at varying states of readiness for change.

Many questions about 12-step approaches remain to be investigated.

What is the optimum duration of 12-step involvement?

What is the best way to maintain involvement?

Should patients receive annual addiction checkups? Semiannual? More often?

If checkups and booster sessions are indicated, how should they be structured?

The Stages of Change component of the model also provides a helpful framework for understanding common recovery issues such as relapse. Inherent in the model is the premise that individuals make multiple attempts at dealing with a problem before they achieve lasting success. This is particularly relevant to drug abuse treatment, where many patients have had prior attempts at recovery through 12-step organizations, drug treatment, or both. By adopting a Stages of Change model, patients and providers are able to view these earlier, unsuccessful attempts not as failures, but as an expected part of the treatment and recovery process. From this perspective, the treatment plan can focus on lessons learned in previous attempts and approaches to minimize the risk of future relapses. While a patient’s continued drug use or repeated relapses may make that individual unsuitable for participation in a particular group or level of care, it does not make him or her unsuitable for treatment.

The Stages of Change model has also provided organizations like Maryhaven with a basis for evaluating where treatment enhancements are needed and which empirically based interventions might be most complementary to the treatment already in place. For example, traditional 12-step-related treatments are weak in addressing the needs of individuals in the precontemplation and, to a lesser degree, the contemplation stages of change. While simple exposure to 12-step fellowship and the program can aid individuals in advancing in the stages of change, it often is not helpful. Indeed a mismatch of “action stage” activities with precontemplation- and contemplation-stage individuals can be counterproductive. This perspective of the treatment and change process makes it evident that improving interventions for individuals in these earlier stages has the potential to improve treatment. At Maryhaven some innovations related to early-stage interventions have included motivational interviewing, motivational incentives, and specialty groups that specifically target consciousness-raising.

12-Step Activities Linked to Processes of Change

| Process of Change | Goal | Step Principle/Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Consciousness-Raising | Increase information about self and problem | Reading 12-step materials, receiving feed-back from peers and professionals, listening to other patients’ stories, viewing recovery films, recovery lectures |

| Social Liberation | Increase social alternatives, behaviors that are not problematic | Helping other addicts, providing media testimonials, testifying for policymakers |

| Emotional Arousal | Experience and express feelings about one’s problems and solutions | Presenting step work in groups, relating to others’ stories in feedback in groups |

| Self-Reevaluation | Assess feelings and thoughts about self with respect to a problem | Clients telling their stories, completing worksheets on the effects of drug addiction on their lives (consequences and plans), step worksheets on character defects, moral inventory, making amends to others, Step 3 worksheet on values and beliefs, spiritual consultation in counseling and fellowships |

| Commitment | Choose to and commit to act, or believe in ability to change | Identifying self as a member of a 12-step program, choosing a home group, openly referring to self as a “drug addict” |

| Countering | Substitute alternatives for problem behaviors | Going to meetings instead of bars or parties, recovery-oriented meditation, prayer, use of AA slogans |

| Environmental Control | Avoid stimuli that elicit problem behaviors | Following 12-step guidance on staying in drug-free places with clean and sober people |

| Reward | Reward self, or be rewarded by others, for making changes | Completing numerous milestones, such as Steps 1 through 12; receiving tokens for lengths of sobriety and willingness; acknowledging “clean time” anniversaries at each meeting and celebrating key milestones |

| Helping Relationships | Enlisti the help of someone who cares | Using counselors, fellow group members, sponsorship |

Source: Adapted from Prochaska and Norcross, 1994.

RESEARCH FOR TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT

Despite the wide use and a growing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of treatment utilizing 12-step principles and practices, relatively little empirical effort has been put into improving this approach. Conducting research on 12-step organizations presents many barriers to investigators, but treatment programs that utilize a 12-step-related approach are readily available for investigation. A review of the 12-step-related treatment research suggests a number of areas where parallels in clinical observations and empirical investigations suggest possibilities for improving 12-step-related treatment.

12-Step Facilitation

A growing body of evidence supports the efficacy of 12-step facilitation (TSF) for increasing patients’ involvement in 12-step organizations and promoting abstinence (Humphreys, 1999). Twelve-step facilitation is an individual counseling approach, detailed in a manual, that incorporates many aspects of the 12-step approach (Nowinski et al., 1992). The recent findings may validate current drug treatment practices; however, little is known regarding how TSF compares in effectiveness to typical drug treatment, which is delivered largely in group settings without the use of a manual. Research on group counseling versions of TSF-type interventions may also be valuable.

The 12 Steps as Cognitive Restructuring

It is common in treatment programs utilizing a 12-step approach to assist patients with developing a command of recovery slogans, which are then used to facilitate problem solving and to address thinking errors. The 12 Steps can themselves be viewed as a process of cognitive restructuring—learning to recognize and change unhealthy thoughts and attitudes (Steigerwald and Stone, 1999). The cognitive restructuring model presents an intriguing opportunity for development of cognitive-behavioral therapy that incorporates the 12-step programs and fellowships rather than viewing them strictly as alternative therapies. Ridding ourselves of either/or views may also open the door to exploring how cognitive behavior and 12-step approaches might fit into a continuum of care in which multiple treatment approaches are viewed as valid and perhaps recommended to patients according to characteristics in their clinical presentation (McCrady, 1994).

Mechanisms of Change

Kingree and colleagues (1999) examined how 183 drug abusers in a 12-step-oriented residential treatment program explained their drug problem. They observed that these patients shifted attributions of causality for their substance abuse from largely societal (external) at admission to personal responsibility at discharge. Interestingly, they also found that societal causality attributions were associated with higher levels of depression. This is certainly consistent with clinical experience, where we frequently observe an association between patients’ accepting personal responsibility for recovery and improvements in affect, cognition, and behavior. The mechanisms of these changes are largely unknown, providing an opportunity for research to improve understanding and possibly enhance the effectiveness of treatment.

Meeting Attendance

Fiorentine and Hillhouse (2000) reported that patients who participated simultaneously in drug treatment and 12-step organizations had better outcomes than individuals who participated exclusively in one or the other. These findings are certainly consistent with clinical observations and empirical findings that incorporating 12-step-related activities into treatment increases the likelihood of 12-step affiliation after treatment. What is not known is what form of integration and how much integration of the two is required or is optimal. Research on these questions would be greatly beneficial.

The same study showed that patients who attended at least one 12-step meeting weekly remained in treatment longer, were more likely to complete treatment, and were more likely to be abstinent after treatment. These findings suggest that patients will benefit from attending at least one 12-step meeting per week; however, they do not provide adequate guidance for best practices. It is common practice in 12-step organizations and in treatment to recommend that patients attend 90 meetings in 90 days. The rationale is related to the notion of immersion in the recovery culture, thinking, language, and behavior; however, without empirical support, it remains largely arbitrary.

Patient-Group Matching, Effective Referral

Research on 12-step group characteristics suggests important differences that can influence clinical practice. In a study of three AA groups, differences were found in perceived social dynamics as well as in the degree to which the groups actually utilized AA program material. In regard to the perceived social dynamics, the groups differed on cohesiveness, independence, aggressiveness, and expressiveness. The researchers suggest these types of differences could be useful for patient-to-group matching (Tonigan et al., 1995). In clinical practice, patients are frequently guided to particular meetings by such personal characteristics as their drug of choice, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and dual diagnosis. Beyond these obvious factors, the group characteristics and patient characteristics with which they may interact remain largely unknown.

Common clinical thinking is that the method of referral can have significant impact on the likelihood of patients benefiting from referral to a 12-step organization. In a pilot study comparing two approaches for making referrals to 12-step organizations, a primarily informational referral approach yielded 0 percent patient follow-through, while an active linking approach yielded a 100 percent patient follow-through. The active referral included a phone call to AA during the patient’s session, an AA member talking to the patient over the phone and arranging a ride to a meeting, and the same AA member calling the patient before the meeting to encourage attendance (Sisson and Mullams, 1981). Further research might lead to optimally efficient and effective referral methods.

Patients’ Response

Twelve-step organizations appear to be helpful to a wide range of AOD-dependent individuals. However, clinical observation and research indicate that not all patients respond equally. It is difficult to predict who will benefit from 12-step organizations. For example, in a study of cocaine-abusing subjects, Weiss and colleagues (2000) reported that no subject characteristics other than severity of baseline drug use were predictive of the extent of 12-step meeting attendance following treatment. Guidance from research would be most useful.

Many patients initially resist affiliation with 12-step organizations for a number of reasons. At times these barriers simply dissolve as patients address their misconceptions about the organizations and gain greater appreciation for the amount of support they will require for successful recovery. Much of this early reluctance is interpreted as denial and more recently as a characteristic of an earlier stage of change. In a preliminary investigation in this area, Morgenstern and colleagues (1996) developed a model for evaluating 12-step affiliation. In addition to meeting attendance, they incorporated other affiliation-related behaviors to explore the depth of client immersion in the 12-step fellowships and program.

After collection of data on 103 patients in two traditional substance abuse treatment programs, the evaluation results yielded three distinct clusters of treatment responders, designated optimal responders, partial responders, and nonresponders. In this sample 31 percent were optimal responders, demonstrating the desired level of commitment, and 42 percent partial responders, who were also positive but more selective in their affiliation with AA. The optimal, partial, and nonresponder clusters were associated with relapse rates of 12.5 percent, 23.8 percent, and 60 percent, respectively (Morgenstern et al., 1996).

Whether these constructs or others are used, these findings are consistent with clinical observations of individual differences in response to the 12-step approach and provide a potential direction for patient-treatment matching and, perhaps more importantly, for improving drug treatment practices.

Project MATCH, a clinical study of psychotherapies for alcohol abuse, provides support for the efficacy of TSF in achieving sustained abstinence and affiliation with 12-step organizations and also supports a number of promising treatment-matching hypotheses (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998). For example, the 3-year outcome report showed that subjects who scored in the top one-third of an anger measure fared best in the motivational enhancement therapy (MET) condition. This type of finding seems promising for guiding treatment planning for individuals with substance abuse and high levels of anger. Of course, many questions remain unanswered, such as: What other characteristics should be considered? What course of treatment is most desirable—MET alone or MET followed by TSF? We currently cannot know how TSF compares with 12-step-related treatment as it is actually carried out in the provider community and therefore do not know whether these findings would generalize to the more comprehensive treatment approach practiced in drug treatment programs.

Length of Involvement

Longitudinal data for 12-step organizations and drug abuse treatment participants is lacking. The recovering community has a general expectation of lifelong involvement in 12-step organizations for continued recovery, but in the normal course of treatment no further professional treatment is planned unless the patient relapses to substance abuse.

CONCLUSIONS

Twelve-step-oriented providers are dedicated to this approach and are not looking to research for replacements of the 12-step approach. While these treatments are effective at achieving their primary goals of 12-step organization affiliation and AOD abstinence, there is little understanding of the processes active in these programs. Some patients do not have an optimal response to current practices, and empirical investigation into improving these programs is lacking. While conducting research on 12-step organizations themselves presents many barriers, treatment programs that incorporate the 12 Steps into their approach are readily available for investigation, and many are eager to incorporate improvements that are compatible with their basic approach and treatment goals.

REFERENCES

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. Alcoholics Anonymous. 3rd ed. New York: AA World Services; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. Came To Believe. New York: AA World Services; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Brown HP, Peterson JH, Cunningham O. Rationale and theoretical basis of a behavioral/cognitive approach to spirituality. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1988;5(1/2):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cook CCH. The Minnesota model in the management of drug and alcohol dependency: Miracle, method or myth. Part 1. The philosophy and the program. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Hillhouse MP. Drug treatment and 12-step program participation: The additive effects of integrated recovery activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Professional interventions that facilitate 12-step self-help group involvement. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23(2):93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PN, Chappel JN. Using AA and other 12-step programs more effectively. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11(2):37–142. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Sullivan BF, Thompson MP. Attributions for the development of substance addiction among participants in a 12-step oriented treatment program. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1999;31(2):129–135. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz E. Not-God: A History of Alcoholics Anonymous. Center City, MN: Hazelden Educational Services; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS. Alcoholics Anonymous and behavior therapy: Can habits be treated as diseases? Can diseases be treated as habits? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(6):1159–1166. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, et al. Modeling therapeutic response to 12-step treatment: Optimal responders, nonresponders, and partial responders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;8(1):45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narcotics Anonymous World Services Office, Inc. Narcotics Anonymous. 5th ed. Van Nuys, CA: NA World Services Office; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1999. NIH Publication No. 00-4180. [Google Scholar]

- Nowinski J, Baker S, Carroll K. Twelve Step Facilitation Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals With Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. Project MATCH Monograph Series Vol. 1. (DHHS Publication No. [ADM]92-1893) [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky ML, et al. Drug Treatment Programs in Los Angeles County. Cited in Fiorentine, R., and Hillhouse, M.P., 2000. Drug treatment and 12-step program participation: The additive effects of integrated recovery activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;18(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Norcross JC. Systems of Psychotherapy: A Transtheoretical Analysis. 3rd ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks-Cole Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Greenfield T. Alcoholics Anonymous, other 12-step movements and psychotherapy in the US population, 1990. Addiction. 1993;88(4):555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson RW, Mullams JH. The use of systematic encouragement and community access procedures to increase attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous and Al-Anon meetings. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1981;8(3):371–376. doi: 10.3109/00952998109009560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steigerwald F, Stone D. Cognitive restructuring and the 12-step program of Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;16(4):321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Ashcroft F, Miller WR. AA group dynamics and 12-step activity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(6):616–621. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. 4th ed. New York: Basic Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RG, et al. Predictors of self-help group attendance in cocaine dependent patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(5):714–719. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]