Abstract

Proponents of a pure public safety perspective on the drug problem hold that drug-involved offenders require consistent and intensive supervision by criminal justice authorities in order to stay off drugs and out of trouble. In contrast, proponents of a thoroughgoing public health perspective commonly argue that clients perform better if they are left alone to develop an effective therapeutic alliance with counselors. Both may be correct, but with respect to different groups of offenders. One approach has shown consistent promise for reducing drug use and criminal recidivism: an integrated public health-public safety strategy that combines community-based drug abuse treatment with ongoing criminal justice supervision. This article presents promising findings from programs implementing this strategy and discusses best treatment practices to meet the needs of both low-risk and high-risk clients.

The drug abuse treatment and criminal justice systems in this country deal with many of the same individuals. Approximately two-thirds of clients in long-term residential drug abuse treatment, one-half of clients in outpatient drug abuse treatment, and one-quarter of clients in methadone maintenance treatment are currently awaiting a criminal trial or sentencing, have been sentenced to community supervision on probation, or were conditionally released from prison on parole (Craddock et al., 1997). Conversely, 60 to 80 percent of prison and jail inmates, parolees, probationers, and arrestees were under the influence of drugs or alcohol during the commission of their offense, committed the offense to support a drug addiction, were charged with a drug- or alcohol-related crime, or are regular substance users (Belenko and Peugh, 1998).

The co-occurrence of drug abuse and crime is not simply an artifact of criminalizing drug possession. Drug use significantly increases the likelihood that an individual will engage in serious criminal conduct. More than 50 percent of violent crimes, including domestic violence, 60 to 80 percent of child abuse and neglect cases, 50 to 70 percent of theft and property crimes, and 75 percent of drug dealing or manufacturing offenses involve drug use on the part of the perpetrator—and sometimes the victim as well (e.g., Belenko and Peugh, 1998; National Institute of Justice, 1999). Sustained abstinence from narcotics is associated with a 40- to 75-percent reduction in crime (e.g., Harrell and Roman, 2001).

In dealing with drug abusers who are criminal justice offenders, many clinicians and service providers support a public health perspective, contending that clients are best served through a focus on treatment, with only minimal involvement of the criminal justice system. They sometimes find themselves at odds with public safety proponents who say that criminal offenders require constant supervision to succeed. Both views are valid, but neither is adequate in itself. Research has shown that neither the pure public safety nor an exclusively public health approach to the problem works fully; instead, it supports an integrated approach that has very specific implications for best practices (see Marlowe, 2002, for review). This article briefly reviews results obtained from one-dimensional public safety and public health strategies and presents promising findings from integrated public health-public safety programs. Finally, the implications for best treatment practices and client-program matching are discussed.

PUBLIC SAFETY STRATEGIES

Drug abuse is illegal and drug abusers are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime and violence. Society often imprisons drug abusers to protect the public and deter further drug use. Yet, within 3 years of release from prison, approximately two-thirds of all offenders, including drug offenders, are rearrested for a new offense, one-half are convicted of a new crime, and one-half are reincarcerated for a new crime or a parole violation (Langan and Levin, 2002). In some studies, 85 percent of drug-abusing offenders returned to drug use within 1 year of release from prison, and 95 percent returned to drug use within 3 years (e.g., Martin et al., 1999). Providing drug abuse treatment within prison typically reduces criminal recidivism rates by only about 10 percentage points (e.g., Gendreau et al., 2001; Pearson and Lipton, 1999). Moreover, in the absence of followup treatment in the community, drug use outcomes are often indistinguishable between offenders who attended in-prison drug abuse treatment and those who received no treatment in prison (e.g., Marlowe, 2002; Martin et al., 1999).

Drug abuse treatment in prison does, however, confer limited, short-term benefits. Studies indicate that in-prison treatment is associated with fewer disciplinary infractions by inmates and reduced absenteeism by correctional staff (Prendergast et al., 2001). More importantly, it increases the likelihood that an inmate will enter drug abuse treatment after release from prison (Martin et al., 1999). Possibly, in-prison services enhance inmates’ motivation for change or prepare them to use drug abuse treatment services once they are in the community or in a transitional-release setting.

Intermediate-sanction programs attempt to reduce drug use and criminal activity, as well as reduce costs, by reducing the emphasis on incarceration and instituting close surveillance of drug-abusing offenders in the community. In these programs, specially trained probation or parole officers with light caseloads typically monitor offenders’ compliance with treatment, make surprise home visits, demand spot-check urine samples, phone-monitor compliance with home curfews or house arrest, or interview employers, friends, and relatives about offenders’ behavior.

Unfortunately, community-based intermediate-sanction programs have had little impact. Approximately 50 to 70 percent of probationers and parolees fail to comply with their release conditions, including drug testing, attendance at drug treatment, and avoidance of criminal activity (e.g., Taxman, 1999a). Moreover, no incremental benefits are obtained from intensive supervised probation and parole programs, electronic monitoring, boot camps, or house arrest (e.g., Gendreau et al., 2001; Taxman, 1999b). Enhanced monitoring of offenders in these programs often leads to a greater detection of infractions and therefore, paradoxically, to seemingly worse outcomes.

In practice, intermediate sanctions typically have been administered in isolation from treatment, with an emphasis on monitoring and sanctioning at the expense of potential rehabilitative functions. When they have been administered in conjunction with treatment, they have generally produced an average of a 10 percentage-point reduction in recidivism (e.g., Gendreau et al., 2001), equivalent to what is commonly obtained from prison-based treatment programs.

PUBLIC HEALTH STRATEGIES

In a pure public health approach to drug-involved offenders, drug abuse or dependence is viewed as a disease that requires treatment rather than confinement or punishment. Accordingly, identifying drug abuse problems among offenders and referring those individuals to treatment in the community is considered to be potentially the most effective way to turn them away from drug abuse and repeated crime. Case management to facilitate referral and coordinate ancillary services for the offender-patients also is believed to influence the success of a public health strategy.

Referral to Treatment

To benefit from treatment, clients must attend the sessions and participate in the interventions. Evidence from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study, which included an evaluation of a nationally representative sample of outpatient and long-term residential drug treatment programs, suggests that 3 months of participation in drug treatment may be a minimum threshold for detecting dose-response effects for the interventions (Simpson et al., 1997). That is, with less than 3 months of treatment, there may not be a significant correlation between time in treatment and outcomes. It also appears that 6 to 12 months of treatment may be a further threshold for observing lasting reductions in drug use. In fact, 12 months of drug abuse treatment may be a median point on the dose-response curve. Approximately 50 percent of clients who complete 12 months or more of drug abuse treatment remain abstinent for an additional year after completing treatment (McLellan et al., 2000).

Unfortunately, attrition in substance abuse treatment programs is unacceptably high. Approximately 70 percent of probationers and parolees drop out of drug treatment or attend irregularly prior to a 3-month threshold, and 90 percent drop out prior to 12 months (e.g., Marlowe, 2002; Taxman, 1999a; Young et al., 1991). Comparable attrition rates are found for drug abuse patients in general (e.g., Stark, 1992). These figures suggest that, on average, only about 10 to 30 percent of clients, in or out of the criminal justice system, receive a minimally adequate dosage of drug treatment. Perhaps as few as 5 to 15 percent achieve extended abstinence.

Of course, these figures are national averages for treatment-as-usual in community-based settings, and it is possible that particular regimens may be more successful at retaining offenders in treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether some treatment interventions may be more acceptable to offender populations or superior for retaining offenders in treatment in noninstitutional correctional settings.

Case Management

The use of specially trained case managers to continuously monitor offenders’ attendance in counseling, take random urine samples to confirm drug abstinence, and provide progress reports to responsible criminal justice authorities is a strategy that seeks to ensure that offenders receive adequate dosages of treatment. Yet, adding case-management services to drug abuse treatment for offenders has produced mixed findings.

In the 1970s, under the rubric of Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime (TASC)–later renamed Treatment Accountability for Safer Communities–hundreds of case-management agencies were founded across the country to identify and refer drug-using offenders to a range of treatment services, monitor their progress in treatment, and report compliance information to appropriate criminal justice authorities. Federal seed funding for TASC was withdrawn in the early 1980s, and now these programs generally rely on a patchwork of local and Federal funds for their continued existence.

TASC agencies operate very differently across jurisdictions, with some programs providing treatment services directly, others developing contractual or formal referral arrangements with treatment programs, and still others making referrals with few formal agency linkages. Generally, there are no systematic sanctions in TASC programs for individuals who do not comply with their treatment regimens.

Early evaluations of TASC programs concluded they were generally effective at identifying substance abuse problems among offenders and making appropriate treatment referrals. Moreover, in a national study, TASC clients were more likely to complete a 3-month threshold of outpatient or residential treatment (48 percent and 57 percent, respectively) than were clients with no current legal involvement (30 percent and 41 percent, respectively) (Hubbard et al., 1988).

A recent evaluation of five large and representative TASC programs concluded, however, that effects on drug use and criminal recidivism were mixed (Anglin et al., 1999). Drug use was significantly lower for TASC clients in three of the five sites, and criminal activity was lower in only two of the sites. These data suggest that the effects of TASC programs vary considerably, depending upon how well the programs carry out their case-management responsibilities. It is reasonable to hypothesize that TASC agencies will be most effective if they have moderate caseloads, meaningful control over the quality of the services their clients receive, and the ability to provide meaningful consequences if clients fail to attend treatment or continue to use drugs.

INTEGRATED PUBLIC HEALTH-PUBLIC SAFETY STRATEGIES

Integrated public health-public safety strategies blend the functions of the criminal justice system and the drug abuse treatment system in an effort to optimize outcomes for offenders (Marlowe, 2002). Substance abuse treatment assumes a central role in these programs, rather than being peripheral to punitive ends, and is provided in clients’ community-of-origin, enabling clients to maintain family and social contacts and seek or continue in gainful education or employment. Responsibility for ensuring clients’ attendance in treatment and avoidance of drug use and criminal activity is not, however, delegated to treatment personnel, who may be unprepared or disinclined to deal with such matters and who have limited power to coerce patients to attend. The criminal justice system maintains substantial supervisory control over offenders and has enhanced authority through plea agreements and similar arrangements to respond rapidly and consistently to infractions in the program.

Noteworthy examples of recent integrated public health-public safety strategies include drug courts and work-release therapeutic communities, which are described in the following sections. While these certainly are not the only conceivable models of integrated strategies, they are the only ones that studies have consistently found effective in reducing drug use and recidivism.

Programs that represent the public health-public safety integration strategy and that have demonstrated effectiveness share a core set of attributes:

They provide treatment in the community.

They offer the opportunity for clients to avoid incarceration or a criminal record.

Clients are closely supervised to ensure compliance.

The consequences for noncompliance are certain and immediate.

Drug Courts

Drug courts constitute a clear paradigm of an integrated public health-public safety strategy that has shown promise for reducing drug use and recidivism among probationers and pretrial defendants. Drug courts are separate criminal court dockets that provide judicially supervised treatment and case-management services for drug offenders in lieu of prosecution or incarceration. The core components of a drug court typically include regular status hearings in court, random weekly urinalyses, mandatory completion of a prescribed regimen of substance abuse treatment, progressive negative sanctions for program infractions, and rewards for program accomplishments.

Common examples of negative sanctions include verbal reprimands by the judge, writing assignments, and brief intervals of detention. Common examples of rewards include verbal praise, token gifts, and graduation certificates. Counseling requirements may also appropriately be decreased when the client complies well with treatment or increased if he or she has poor attendance or participation or other problems. Clients who satisfactorily complete the program may have their current criminal charges dropped or may be sentenced to time served in the drug court program. Defendants are generally required to plead guilty or “no contest” as a precondition of entry into drug court. Therefore, termination from the program for non-compliance ordinarily results in a criminal drug conviction and sentencing to supervised probation or incarceration.

The evidence is clear that drug courts can increase clients’ exposure to treatment. Reviews of nearly 100 drug-court evaluations concluded that an average of 60 percent of drug court clients completed a year or more of treatment, and roughly 50 percent graduated from the program (Belenko, 1998, 1999, 2001). This compares favorably to typical retention rates in community-based drug treatment programs where, as noted, more than 70 percent of clients on probation and parole drop out of drug treatment or attend irregularly within 3 months, and 90 percent drop out in less than 1 year.

Promising, although less definitive, is the evidence with regard to the effects of drug courts on drug use and crime. Two experimental studies have compared outcomes between participants randomly assigned to either drug court or a comparable probationary condition. In one study, the Maricopa County (Arizona) Drug Court was found to have had no impact on rearrest rates 12 months after admission to drug court (Deschenes et al., 1995). However, a significant “delayed effect” was detected at 36 months, at which time 33 percent of the drug court participants had been rearrested, compared to 47 percent of subjects in various probationary tracks (Turner et al., 1999).

Elements of Successful Programs.

Effective programs such as drug courts and work-release therapeutic communities have the following elements in common:

Treatment in the community. For treatment gains to generalize and be sustained, clients require opportunities to practice new skills in the community environment. In contrast, incarceration removes individuals from family and social supports, interferes with employment or education, and exposes them to antisocial peer influences.

Opportunity to avoid a criminal record or incarceration. Treatment completion and drug abstinence are reinforced by removal of criminal justice sanctions, and clients can avoid the debilitating stigma of a criminal record.

Close supervision. The programs include random weekly urinalyses, status hearings with criminal justice authorities, and monitoring of official rearrest records. Clinicians provide regular progress reports to supervising authorities and may provide testimony at status hearings. As a result, clients are less apt to drop out of the system through inattention and cannot exploit gaps in communication.

Certain and immediate consequences. Clients agree to specified sanctions and rewards that can be readily applied without having to hold new formal hearings with the full range of due process protections. Termination for non-compliance or new infractions automatically results in a criminal conviction and criminal disposition.

Similarly, in a randomized study of the Baltimore City Drug Treatment Court, 48 percent of drug court clients and 64 percent of adjudication-as-usual control subjects were rearrested within 1 year of admission (Gottfredson and Exum, 2002). At 2 years post-admission, 66 percent of the Baltimore drug court participants and 81 percent of the controls had been rearrested for some offense, and 41 percent of the drug court participants and 54 percent of the controls had been rearrested for a drug-related offense (Gottfredson et al., 2003).

Nearly 100 quasi-experimental evaluations have compared outcomes between drug court participants and nonrandomized comparison groups. In the majority of these evaluations, drug court clients achieved significantly greater reductions—differences of approximately 20 to 30 percentage points during treatment and 10 to 20 percentage points after treatment—in drug use, criminal recidivism, and unemployment than did individuals on standard probation or intensive probation (Belenko, 1998, 1999, 2001). The magnitudes of the posttreatment effects are comparable to the 15 percentage-point reduction in recidivism obtained in the two experimental studies reviewed above.

It is important to note, however, that many drug court evaluations have used systematically biased comparison samples, such as offenders who refused, were deemed ineligible for, or dropped out of the interventions. This may have led to an overestimation of positive outcomes for drug court clients in some studies because the comparison subjects are likely to have had more severe criminal histories or lower motivation for drug abuse treatment from the outset. Further, most of the studies evaluated outcomes only during the course of drug court or up to 1 year postdischarge, and hardly any studies have assessed substance-use outcomes after discharge. Thus, we know little about how drug court clients generally fare after the criminal justice supervision ends.

These limitations in the extant research on drug courts led the congressional General Accounting Office (GAO) to conclude there are insufficient data available to gauge the effectiveness of federally funded drug court programs in this country (GAO, 2002). In response to the GAO report, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) released a request for proposals for long-term client-impact evaluations of up to 10 drug courts that will include assessments of postprogram recidivism, drug use, employment, and psychosocial functioning and will include suitable comparison conditions. These evaluations are expected to shed further light on the long-term impact of drug courts.

Work-Release Therapeutic Communities

Encouraging results have been reported for therapeutic community (TC) programs targeted to individuals paroled from prison or conditionally transferred to a correctional work-release facility in the community. TCs are residential treatment programs that isolate clients from drugs, drug paraphernalia, and affiliations with drug-using associates. The peers in TCs influence each other by confronting negative personality traits, punishing inappropriate behaviors, rewarding positive behaviors, and providing mentorship and camaraderie. Clinical interventions commonly include confrontational encounter groups, process groups, community meetings, and altruistic volunteer activities.

Three-year longitudinal evaluations of geographically diverse correctional TC programs (Knight et al., 1999; Martin, et al., 1999; Wexler et al., 1999) suggest that, to be maximally effective, TC services should be provided along the full continuum of reentry, ranging from in-prison treatment, through work-release treatment, to continuing outpatient treatment. In all studies, in-prison TC treatment without after-care had no appreciable effect on drug use or rates of return to custody. However, offenders who completed a work-release TC exhibited significant reductions—of approximately 10 to 20 percentage points—in rearrests, returns to custody, and drug use. Moreover, completion of both in-prison and work-release programs was associated with a reduction of 30 to 50 percentage points in new arrests or returns to custody.

As with drug courts, these TC studies made inherently biased comparisons, such as contrasting TC dropouts with graduates, and comparing offenders who voluntarily entered aftercare to those who did not. As a result, it is difficult to be confident of the actual magnitude of the effects. Nevertheless, the results underscore the importance of providing aftercare services to offenders once they are released from prison. It is not sufficient to provide inmates with referral to a community treatment program. It is essential to prepare them for what to expect, to facilitate the referral by transferring the relevant paperwork and clinical information to the referral source, and to follow up to ensure that the individual has completed the referral (Cornish and Marlowe, in press). Moreover, as noted earlier, providing in-prison TC treatment may increase the probability that an inmate will continue in aftercare services. It would seem optimal to begin the continuum of drug treatment, including initial assessments and motivational enhancement interventions, prior to the inmate’s release.

Unfortunately, TCs are the only community-reentry programs that have been systematically studied. There are virtually no outcome data available on other types of postprison initiatives. Recently, NIDA released a request for applications to develop the Criminal Justice-Drug Abuse Treatment Services Research System, which is intended to, among other things, provide support for controlled studies of various community-reentry strategies for drug-involved offenders.

BEST PRACTICES

Proponents of a pure public health perspective commonly argue that the involvement of criminal justice authorities in treatment can be disruptive and potentially harmful for a number of reasons:

Clients may mistrust treatment providers who are allied with law enforcement and may not confide important clinical information for fear it will be used against them.

Treating sick people like criminals may breed coun-tertherapeutic feelings of resentment, hostility, or hopelessness.

Forcing clients to spend time in criminal justice settings may have the unintended consequence of socializing them into a milieu of antisocial behavior.

Criminal justice supervision is expensive and time-consuming. Judges, bailiffs, and probation and parole officers cost money that may then not be available for formal drug abuse treatment.

Proponents of a pure public safety perspective contend instead that:

Drug-involved offenders are characteristically impulsive and irresponsible.

These offenders frequently fail to meet their obligations and often do not stay out of trouble unless they are closely monitored and face immediate, consistent, and severe consequences for their noncom-pliance.

Such close monitoring may itself be therapeutic because it instills a sense of accountability and provides highly effective behavioral contingencies.

Neither the pure public health position nor the pure public safety position is often borne out by research. The available evidence suggests that both may be correct, but with reference to different clients. Some clients perform better if they are left alone to develop an effective therapeutic alliance with their counselor and to focus on their problems and recovery in treatment. Others require consistent and intensive supervision by criminal justice authorities in order to succeed.

The Risk Principle: A Foundation for Best Practices

Outcome studies indicate that intensive interventions are best suited to high-risk offenders who have relatively more severe criminal dispositions and drug-use histories, but may be ineffective or contraindicated for low-risk offenders (e.g., Gendreau et al., 2001). This is known as the “Risk Principle” in the criminal justice literature and is attributed to the idea that low-risk offenders are less likely to be on a fixed antisocial trajectory and are more likely to adjust course readily after a run-in with the law. Therefore, intensive treatment and monitoring may offer little incremental benefit for these individuals, while the cost is substantial. High-risk offenders, on the other hand, are more likely to require intensive structure and monitoring to alter their entrenched negative behavioral patterns.

The greatest risk factors reported in the literature for failure in offender rehabilitation programs are a younger age during treatment (typically under age 25), an earlier age of involvement in crime (especially violent crime prior to age 16), an earlier age of beginning drug use (typically prior to age 14), a comorbid diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (APD) or psychopathy, previous failed efforts in drug treatment or a criminal diversion program, and first-degree relatives with drug abuse problems or criminal histories (e.g., Gendreau, 1996). These risk factors are labeled “static” because they are historical in nature and are generally unaffected by clinical interventions. “Dynamic” risk factors, which can be targeted for change during treatment, include such things as antisocial attitudes, criminal associations, and gang membership.

A Basis for Matching Patients to Supervision Regimens.

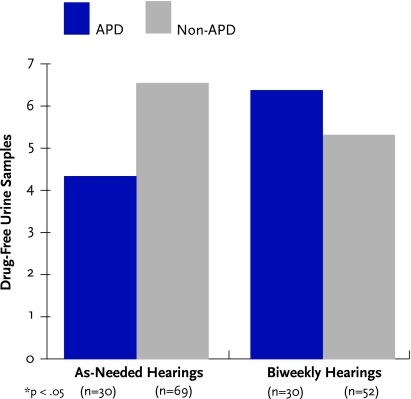

During a 14-week misdemeanor drug court program, clients with antisocial personality disorder (APD) who were assigned to biweekly judicial status hearings turned in significantly more drug-free urine samples than similarly diagnosed offenders without a fixed schedule for hearings. Drug court clients without an APD diagnosis, conversely, did better when assigned to as-needed hearings.

Source: Festinger et al., Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2002. Copyright 2002 by D.S. Festinger, D.B. Marlowe, P.A. Lee, K.C. Kirby, G. Bovasso, A.T. McLellan, and Elsevier Press. Used with permission.

The research program at the Treatment Research Institute (TRI) at the University of Pennsylvania has validated the Risk Principle among drug court clients. With funding from NIDA and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), TRI randomly assigned misdemeanor drug court clients either to an intensive level of judicial supervision involving biweekly status hearings in court, or to a low level of supervision in which they were monitored by treatment personnel and had status hearings (see “A Basis for Matching Patients to Supervision Regimens”) only as needed in response to sustained noncompliance or serious infractions. The results revealed no differences for participants as a whole in counseling attendance, urinalysis results, graduation rates, or self-reported substance use or criminal activity during treatment or at 6 months or 12 months postadmission (Marlowe et al., 2002; Marlowe et al., 2003a).

Importantly, however, the study showed a significant interaction effect, depending on participants’ risk status. Participants who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for APD or had prior experiences in drug abuse treatment attained significantly greater drug abstinence and were significantly more likely to succeed in graduating from the drug court program when they were assigned to biweekly hearings. Conversely, clients without APD or a prior history in drug treatment performed better when they were assigned to as-needed hearings (Festinger et al., 2002). These same findings were replicated in two additional jurisdictions, in rural and urban communities and serving both misdemeanor and felony offenders (Marlowe et al., 2003b; Marlowe et al., in press).

In the replication studies, the magnitudes of the interaction effects were quite large. For instance, misdemeanor participants with a prior drug treatment history provided substantially more drug-free urine specimens during the first 3 months of drug court (11.50 versus 2.67) and were substantially more likely to graduate successfully from the program (83 percent versus 17 percent) when they were assigned to biweekly status hearings as opposed to as-needed hearings. Similarly, felony participants with APD reported engaging in substantially fewer days of alcohol intoxication when they were assigned to biweekly status hearings as opposed to as-needed hearings (0.50 versus 4.83).

The large magnitude of these effects made it ethically necessary to stop the studies and to institute remedial procedures for the high-risk participants assigned to the as-needed condition. The resulting small cell sizes (n=6 per cell in some analyses) do raise concerns about whether the study samples were adequately representative of drug court clients generally. Because the findings were reproduced in sequential experimental studies and are supported by a previously validated criminal justice theory (i.e., the Risk Principle), we have considerable confidence in their reliability. Nevertheless, it is essential to replicate this work in new settings with a larger number of participants.

It is also important that the interaction effects, although hypothesized in advance, were not under direct experimental control. TRI is currently conducting a prospective matching study in which drug court clients are randomly assigned to different schedules of judicial status hearings on the basis of an assessment of whether they have APD or a prior drug treatment history. The results of this work will permit an estimate of the effect size and relative costs and benefits of assigning drug offenders to different service tracks in drug court based upon their risk level.

Our finding that APD and drug treatment history were the most robust indicators of risk level among the drug court clients in our studies is quite consistent with prior research on the greatest risk factors for criminal reoffending (e.g., Gendreau, 1996). It is, however, possible that other risk factors will emerge in future matching studies and permit a more sensitive classification of high-risk and low-risk offenders. Further research is also needed to interpret the influence of prior drug treatment history. It is an open question whether this variable reflects the severity of participants’ drug problems, past negative experiences with standard drug treatment, or some other, unknown influence. Further inquiry is needed to gain a definitive grasp of the nature of this interaction effect.

From Risk to Regimen

In the three jurisdictions TRI studied, approximately 50 percent of the felony and misdemeanor drug court clients met criteria for being at high risk, meaning they had APD, a prior drug treatment history, or both. These findings suggest that no more than half of drug offenders might reasonably be expected to perform adequately in the type of low-intensity, nonjudicially managed diversionary intervention exemplified in recent State policy initiatives such as Proposition 36 or Proposition 200 (see “States Move to Low-Intensity Intervention for Nonviolent Drug Offenders”). A substantial proportion of drug offenders could be at risk for failing in such an intervention, suggesting that criminal diversion statutes should incorporate some mechanism to permit poorly responding individuals to be readily transferred to a judicially managed program.

The findings have further implications for best treatment practices and for ethical guidelines for drug treatment providers (see “Confidentiality Guidelines for Integrated Approaches”).

Ideally, there might be (at least) two tracks in treatment programs, involving different service arrangements with courts and probation and parole offices. Low-risk clients could be treated with the general client population. High-risk clients, however, might be treated separately in a track that provides routine progress reports to criminal justice authorities and has full-time court liaisons who can accompany clients to status hearings in court or to probation or parole offices. In practice, such court liaisons typically are professional case managers who may be employed either by the substance abuse treatment system or by the criminal justice system through law enforcement or substance abuse block grants or through specific drug court implementation grants.

Integrated approaches should incorporate the ability to readily transfer clients between tracks according to their actual conduct in treatment. Demonstrated success in the program could be rewarded with reduction of monitoring requirements, whereas evidence of poor performance could be met with an increase of treatment services or of supervisory obligations such as more frequent urinalyses or court hearings. In truly integrated programs, the criminal justice system retains ultimate jurisdiction or authority over clients; therefore, it is possible to increase the intensity of services readily in response to infractions without having to hold new court hearings with formal due-process requirements such as the right to notice, to counsel, and to present evidence.

States Move to Low-Intensity Intervention for Nonviolent Drug Offenders.

A few States have passed referenda aimed at diverting drug-possession offenders into community-based treatment in lieu of judicial supervision. California’s Proposition 36 and Arizona’s Proposition 200 were each passed by approximately two-thirds of voters. These statutes require, among other things, that nonviolent offenders convicted of drug possession, drug use, or transportation for use be sentenced to probation with drug abuse treatment as a mandatory condition. Upon successful completion of treatment and substantial compliance with probation, the offender is entitled to have his or her arrest record and conviction record expunged. This would entitle the individual to truthfully respond on an employment application or similar document that he or she has not been arrested for a drug-related offense.

Many jurisdictions offer this form of diversion—sometimes called “Deferred Judgment” or “Probation Without Verdict”—to first- or second-time offenders charged with relatively minor crimes such as disturbing the peace, public intoxication, petty theft, or driving while intoxicated. However, Proposition 36 and Proposition 200 extend the opportunity, as a matter of right, to all nonviolent drug-possession offenders who are not currently charged with another felony or serious misdemeanor offense and who have not been convicted of or incarcerated for such an offense within the preceding 5 years. Moreover, Proposition 36 and Proposition 200 generally provide offenders with three chances to succeed in the program. If an offender violates a drug-related condition of probation or is charged with a new drug-possession offense, the statutes simply provide for a second and then a third opportunity at diversion unless, according to the statute, the State can make the difficult showing that the offender is a “danger to others” or is “unamenable to drug treatment.”

A ballot initiative comparable to Propositions 36 and 200 was passed in the District of Columbia, and the Hawaii State Legislature enacted a similar law in 2002. Equivalent referenda were withdrawn from the 2002 elections in Florida and Michigan on technical, procedural grounds and are likely to be placed on the ballot again for the next elections. Kansas and several other State legislatures also are considering bills containing similar statutory provisions. Yet, despite their widespread and rapidly growing appeal, no reliable data are available on the efficacy of these types of diversionary programs in general or on specific initiatives such as Proposition 36 and Proposition 200.

Studies of Proposition 36 are currently under way in California. Various counties have been implementing Proposition 36 differently at the programmatic level. For instance, some counties are administering Proposition 36 through the existing drug court system using ongoing court hearings. Comparisons of client outcomes across different service models may reveal the best way to implement these types of initiatives.

The content of treatment might also be tailored to clients’ risk levels. Highly structured behavioral or cognitive-behavioral interventions are ideally suited for many offenders, particularly those identified as “high risk” (e.g., Cornish and Marlowe, in press; Gendreau et al., 2001). In contrast, insight-oriented or group-process interventions have been associated with increased rates of drug use and recidivism among high-risk offenders, and educational or drug-awareness sessions have been shown to have no effect for any offenders (e.g., Pearson and Lipton, 1999; Taxman, 1999b). The worst outcomes have been seen with insight-oriented treatments that presume a wellspring of anxiety, depression, or low self-esteem underlies antisocial conduct. The best results have been obtained from programs that focused on restructuring clients’ distorted antisocial cognitions, correcting their erroneous assumptions about the motives of others, and teaching adaptive problemsolving, communication, and coping skills. Of course, observable and diagnosable symptoms of depression or anxiety should also be targeted in conjunction with any treatment regimen.

Furthermore, in the most successful programs, staff members have been in a position to reliably detect clients’ accomplishments and infractions in the program and to apply rewards for desired behaviors and negative sanctions for undesired behaviors (e.g., Harrell and Roman, 2001; Marlowe and Kirby, 1999; Taxman, 1999b). For instance, the most effective programs regularly monitor clients’ substance use through random breathalyzer tests and urinalyses. Drug-free test results are met with rewards, such as reduced monitoring requirements, reduced criminal sanctions, or goods and services that support a productive lifestyle. Drug-positive results, on the other hand, are met with such sanctions as loss of privileges, increased counseling requirements, or a brief return to detention. If a particular program’s philosophy or structure cannot easily accommodate such an approach, that program might consider having a separate, intensive, behavioral or cognitive-behavioral track for high-risk offenders or might consider not accepting referrals to treat such offenders.

Pharmacological interventions are seriously underutilized in the criminal justice system despite the fact that several medications have demonstrated success for reducing substance use and crime among offenders (e.g., Cornish and Marlowe, in press). Methadone maintenance treatment, in particular, has been consistently demonstrated in numerous experimental studies to reduce drug use and criminal activity among opiate addicts, with effects many times the size of hospital-based detoxification, drug-free out-patient treatment, and residential treatment (e.g., Platt et al., 1998). In a controlled experimental study, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania similarly found that Federal probationers who were randomized to receive naltrexone in combination with psychosocial counseling had lower rates of opioid-positive urines and were less likely to be reincarcer-ated for probation violations than those receiving psychosocial counseling alone without naltrexone (Cornish et al., 1997). Subsequent studies by the same investigators are examining the effects of oral and depot naltrexone among State parolees, probationers, and drug court clients. Preliminary data from those studies suggest that oral naltrexone may be more effective in retaining parolees in treatment than standard psychosocial treatment alone.

It is possible that opioid-antagonist medications such as naltrexone may be more palatable to policy-makers and criminal justice practitioners because they are not perceived as substituting one addictive substance for another, as is commonly ascribed to methadone. Further research is needed to evaluate the acceptability and effects of these types of medications in correctional settings, and to identify and resolve barriers to the use of efficacious medications with criminal justice clients.

CONCLUSION

Research evidence suggests that public health proponents and public safety proponents may have different types of drug-involved offenders in mind. Certain offenders might be well suited to being diverted into treatment and given an opportunity to avoid the stigma of a criminal record. Others require intensive monitoring and consistent consequences for noncompli-ance in treatment. Just as clinical interventions should be targeted to the specific needs of each individual, the degree to which criminal justice authorities and drug treatment providers actively coordinate their functions for a particular client should be based upon a careful assessment of that client’s risk status and ongoing monitoring of his or her progress in treatment. Programs that jointly allocate responsibility for clients to criminal justice and drug abuse treatment professionals are in the best position to respond readily by increasing or decreasing their coordination of efforts, depending upon clients’ performance in the program. This provides maximum flexibility and access to resources for handling an impaired and potentially resistant population.

Confidentiality Guidelines for Integrated Approaches.

Drug treatment providers are typically socialized to maintain strict confidentiality and nonporous professional boundaries between themselves and criminal justice authorities. The author’s drug court studies suggest this might, indeed, be therapeutic for low-risk clients who may need a safe and discreet setting to focus on their problems. Such an approach, however, would appear to be contraindicated for high-risk clients who could deliberately evade detection of infractions or might exploit gaps in communication and monitoring.

Many clinicians misunderstand their ethical and legal obligations with regard to confidentiality for criminal justice clients. Federal law and most State laws expressly permit substance abuse treatment programs to disclose information about clients to criminal justice officials who have made program participation a condition of the disposition of a criminal proceeding, probation, parole, or conditional release from prison or jail (e.g., Marlowe, 2001). Disclosure must be limited to those individuals who need the information to meet their duty to monitor the client’s progress. Notably, Federal law prohibits the use of such information to investigate or prosecute any new charge against the client. The information can be used only to monitor the client’s progress during the immediate treatment episode.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) does not add substantive restrictions on the sharing of health-related information in this context. Rather, HIPAA requires treatment providers to clearly inform clients about how their personal health information will be used and to give them an opportunity to object to such uses. Clinicians may share treatment information with criminal justice professionals so long as they provide clients with appropriate notice of their agency’s privacy practices and the limitations on confidentiality, and they obtain specific authorizations from the client to disclose the information in that manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was supported by NIDA grants number R01-DA-1-3096, R01-DA-1-4566, and P50-DA-0-7705, with supplemental funding from CSAT, and by contract #97-IJ-CX-0013 from the National Institute Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views of NIDA, CSAT, NIJ, or ONDCP.

REFERENCES

- Anglin MD, Longshore D, Turner S. Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime: An evaluation of five programs. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 1999;26(2):168–195. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S. Research on drug courts: A critical review. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1998;1:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S. Research on drug courts: A critical review: 1999 update. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1999;2(2):1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S. Research on Drug Courts: A Critical Review: 2000 Update. New York: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Peugh J. Behind Bars: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population. New York: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish JW, et al. Naltrexone pharmacotherapy for opioid dependent federal probationers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish J, Marlowe DB. Alcohol Treatment in the Criminal Justice System. In: Johnson BA, Ruiz P, Galanter M, editors. Alcoholism: A Practical Handbook. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Craddock SG, et al. Characteristics and pretreatment behaviors of clients entering drug abuse treatment: 1969 to 1993. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23(1):43–59. doi: 10.3109/00952999709001686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes EP, Turner S, Greenwood P. Drug court or probation? An experimental evaluation of Maricopa County’s drug court. Justice System Journal. 1995;18(1):55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, et al. Status hearings in drug court: When more is less and less is more. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau P. The Principles of Effective Interventions With Offenders. In: Harland AT, editor. Choosing Correctional Options That Work: Defining the Demand and Evaluating the Supply. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau P, Smith P, Goggin C. Treatment Programs in Corrections. In: Winterdyk J, editor. Corrections in Canada: Social Reactions to Crime. Toronto: Prentice Hall; 2001. pp. 238–263. [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office. Drug Courts: Better DOJ Data Collection and Evaluation Efforts Needed To Measure Impact of Drug Court Programs. Washington, DC: GAO; 2002. Publication No. GAO-02-434. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Exum ML. The Baltimore City Drug Court: One-year results from a randomized study. Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS, Kearley B. Effectiveness of drug courts: Evidence from a randomized trial. Criminology & Public Policy. 2003;2(2) www.criminologyandpublicpolicy.com/search/abstrGottfredson03.php. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell A, Roman J. Reducing drug use and crime among offenders: The impact of graduated sanctions. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31(1):207–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, et al. The Criminal Justice Client in Drug Abuse Treatment. In: Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, editors. Compulsory Treatment of Drug Abuse: Research and Clinical Practice. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1988. pp. 57–80. NIDA Research Monograph No. 86 (NIH Publication no. ADM-88–1578) [Google Scholar]

- Knight K, Simpson DD, Hiller ML. Three-year reincarceration outcomes for in-prison therapeutic community treatment in Texas. Prison Journal. 1999;79(3):337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Langan PA, Levin DJ. Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB. Coercive treatment of substance abusing criminal offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice. 2001;1:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB. Effective strategies for intervening with drug-abusing offenders. Villanova Law Review. 2002;47:989–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Lee PA. The judge is a key component of drug court. National Drug Court Institute Review in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Lee PA. The role of judicial status hearings in drug court. Offender Substance Abuse Report. 2003a;3(3):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, et al. A randomized, controlled evaluation of judicial status hearings in drug court: 6- and 12-month outcomes and client-program matching effects [abstract] Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66:S111–S112. Presentation at the 64th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Quebec City, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, et al. Are judicial status hearings a “key component” of drug court? During-treatment data from a randomized trial. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 2003b;30:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Kirby KC. Effective use of sanctions in drug courts: Lessons from behavioral research. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1999;2(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SS, et al. Three-year outcomes of therapeutic community treatment for drug-involved offenders in Delaware. Prison Journal. 1999;79:294–320. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Justice. Annual Report on Drug Use Among Adult and Juvenile Arrestees. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson FS, Lipton DS. A meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of corrections-based treatments for drug abuse. Prison Journal. 1999;79(4):384–410. [Google Scholar]

- Platt JJ, et al. Methadone maintenance treatment: Its development and effectiveness after 30 years. In: Inciardi JA, Harrison LD, editors. Heroin in the Age of Crack-Cocaine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 160–187. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML, Farabee D, Cartier J. The impact of in-prison therapeutic community programs on prison management. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2001;32(3):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Stark MJ. Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: A clinically oriented review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS. Graduated sanctions: Stepping into accountable systems and offenders. Prison Journal. 1999a;79:182–204. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS. Unraveling “what works” for offenders in substance abuse treatment services. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1999b;2(2):93–134. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, et al. Perceptions of drug court: How offenders view ease of program completion, strengths and weaknesses, and the impact on their lives. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1999;2(1):61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Usdane M, Torres L. Alcohol, Drugs and Crime: Vera’s Final Report on New York State’s Interagency Initiative. New York: Vera Institute of Justice; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler HK, et al. Three-year reincarceration outcomes for Amity in-prison therapeutic community and aftercare in California. Prison Journal. 1999;79:321–336. [Google Scholar]