Abstract

Providers of treatment for opioid addiction have entered a new era of accountability, as Federal and State regulators increasingly demand objective evidence of treatment effectiveness. Since the length of treatment is associated with success of treatment, opioid treatment programs that demonstrate an ability to retain patients can make a strong case that they are effective. The challenge to opioid treatment providers is to examine their practices and begin organizational change to incorporate scientifically proven practices to improve patient retention. The challenge to the research community is to partner more effectively with community-based providers to help them through the transition.

May 18, 2001, was a landmark day in the history of what was once called methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) or, more recently, opiate substitution (or replacement) treatment. On that date, Federal oversight of MMT shifted from the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal regulating authority since 1972, to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) (DHHS, 2001). The main objective of the change in oversight is to move programs toward stricter accountability for patient outcomes, such as decreased drug use, reduced criminal behavior, and improved social functioning. Increasingly, programs will need to do more to maintain their licenses than simply adhere to the regulations governing the delivery of methadone, LAAM, and other medications for treating opioid addiction. They also will have to demonstrate that they measure and meet criteria for acceptable levels of treatment effectiveness and patient benefit.

The new rules also give providers more flexibility to adopt scientifically validated outcome-enhancing practices. To reflect the emphasis on a variety of potentially effective practices that go beyond methadone maintenance, SAMHSA has instituted the label “opioid treatment program” (OTP).

This article offers an OTP director’s perspective on how programs can succeed in the new era. OTPs must draw on scientific research, which has provided a wealth of studies to inform clinical practice. A key principle that has emerged is that the length of time a patient stays in treatment (“retention”) is a highly significant indicator of program quality; measured repeatedly, it is a tool for assessing progress in improving outcomes. To achieve and document greater patient retention as well as other desirable patient outcomes, many OTPs will need to make sometimes far-reaching changes in their operations and offerings. Collaboration between providers and researchers will be essential to solving the many practical problems OTPs must overcome to fully implement science-based treatments.

PATIENT RETENTION: WHAT RESEARCH SHOWS

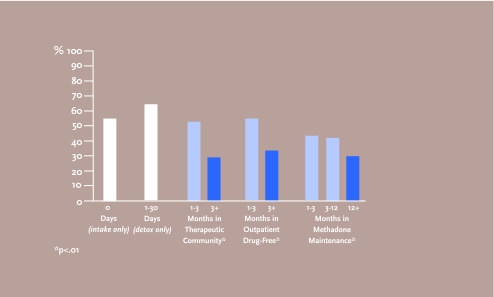

There is clear and abundant evidence that longer duration of treatment is associated with better patient outcomes (see Figure 1), both during methadone maintenance and after successful completion of treatment (that is, gradual tapering from methadone with psychosocial stability and no return to opioid addiction) (Ward et al., 1998). The studies suggest that treatment should last no less than 1 year, and that 2 or 3 years of treatment produces superior outcomes. No studies support setting a fixed limit on duration of treatment. Thus, patient retention is a key performance indicator for OTPs to routinely measure and evaluate, and taking steps to increase patient retention is a potentially valuable strategy for improving patient outcomes.

FIGURE 1. Time in Treatment and Daily Opioid Use in Year Following Discharge.

Duration of treatment is a key measure for assessing the quality of a treatment program because it is directly related to successful outcomes. In a study with 3,248 patients, daily opioid use in the year following discharge from treatment declined in direct proportion to the length of time patients stayed in treatment, regardless of the treatment modality—therapeutic community, outpatient drug-free, or methadone maintenance. Patients who simply underwent detox without followup treatment had the poorest outcomes. Decreased criminal behavior showed a similar direct relationship to length of treatment.

Source: Simpson and Sells, 1982.

Researchers have studied a number of patient-related and program-related factors to see whether they affect retention of patients in treatment. Patient-related factors include age, race, ethnicity, sex, the number of substances abused, psychopathology, employment, social support network, and level of motivation to quit drugs. Findings about which of these factors affect retention have been mixed; but even if there were clear findings, they would be of little practical help to providers seeking to improve retention and outcomes. For both practical and ethical reasons, OTPs cannot select for admission only those applicants whose characteristics indicate a higher probability of success in treatment.

OTPs, then, must look to program-related factors for opportunities to make changes that will improve their patients’ outcomes. Among the factors that can enhance success, according to studies, are:

Use of individually determined methadone doses and higher doses (≥60 mg) (Maddux et al., 1997);

Individualized treatment plans that identify needs for employment, family, legal, financial, and other supplemental services (Joe et al., 1991) and access to such services (Condelli, 1993);

Use of contingency contracting with negative incentives (for example, treatment sanctions; Saxon et al., 1996) or positive incentives (such as medication take-home privileges; Chutuape et al., 1999) linked to urinalysis results and attendance at dosing and counseling sessions;

Counselor behaviors and ability to form a working alliance with patients (Blaney and Craig, 1999);

Staff acceptance of the philosophy of maintenance treatment, which sees opioid addiction as a medical illness that requires medication and counseling for an indefinite period (Caplehorn et al., 1998);

Frequency of counseling contacts and other program features (Magura et al., 1999); and

Greater experience and involvement with treatment on the part of the OTP director (Magura et al., 1999).

IMPLEMENTING NEW PRACTICES: OBJECTIVES AND BARRIERS

Key research-proven objectives that OTPs can adopt to improve patient retention and other outcomes include acquiring research information; identifying cost-effective research-based interventions; securing high-quality social services; and tracking retention rates. As they pursue these objectives, OTPs will encounter practical barriers in the areas of resources and staffing. They will also face information gaps where research to date has not provided key answers and where implementation-oriented research will be critical to an efficient transition to more effective treatment.

Learning to acquire, evaluate, and use research will be a necessary first task for many OTPs. In this author’s experience, OTP managers and their staffs are largely unaware of specific research findings on the relationship of treatment variables to retention and outcomes. As knowledge is an important element of change, the research community and leaders in OTP associations could do a better job of disseminating findings to the treatment community. CSAT’s Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series, NIDA’s “Blending Research and Practice” meetings, this new NIDA journal, and the training efforts of the national network of Addiction Technology Transfer Centers (ATTCs) are examples of a good start in that direction. However, many programs do not take advantage of those resources. Furthermore, OTP managers who do inform themselves must also facilitate knowledge dissemination to their staffs.

Having reviewed the literature linking program characteristics to retention, an OTP manager may be able to identify several ways to modify or enhance a program to improve outcomes. At this juncture, an important objective will be to select for implementation those that use the OTP’s resources cost-effectively—in other words, that are worth the investment. This decision can be difficult, in part because researchers have tended to test interventions without sufficient attention to the resource limitations of OTPs. For example, one research project found that a take-home incentive program—granting take-home privileges to patients who reduce their drug use—had a positive effect on outcomes (Chutuape, 1999); however, the resources devoted to the study were greater than most OTPs enjoy. No estimate was made of how much an agency might need to spend to implement and sustain a take-home incentive program, or whether such a program might yield a better return on the investment of agency resources than, say, training and supervising counselors to be more proficient in the use of motivational interviewing. More research focus on the cost-effectiveness of various interventions or staff training strategies would be extremely valuable.

Once an OTP director has selected a science-based intervention or program component for implementation, staff training will be critical for success. This is another area, however, in which research has not yet provided OTP managers with much guidance. If, for example, an OTP manager, recognizing the counselor’s important role in improving patient retention, wished to improve staff skills in the use of motivational interviewing, how would that best be accomplished? What kind of training, delivered by a trainer with what qualifications, would yield the highest probability of skills acquisition and incorporation of those skills in clinical practice? Scientific research to help managers resolve some of these questions would be very welcome.

Scientific research has shown that outcomes improve when individualized treatment plans match service delivery to individual patients’ needs and appropriate high-quality social services are provided. In attempting to meet this objective, OTPs will again confront issues of developing and allocating resources and effecting organizational change.

With resources limited by low reimbursement rates, many OTPs look to their communities for quality health and social services for their patients. Unfortunately, many communities and social service providers view OTPs and their patients with antipathy or disdain. Often, they misunderstand opiate agonist therapy, consider OTPs little more than legalized drug dealers, and consequently want nothing to do with an agency or its patients. In addition, many social service providers seem to view heroin addiction as an intractable condition brought on by willful mis-conduct and so reject or give lowest priority to patients referred by OTPs. The research community has in recent years publicized the effectiveness of opioid addiction therapy, encouraging the public to correctly characterize opioid addiction as a chronic medical disorder. In some areas this activity has led to significantly better acceptance of OTPs and their patients. Sadly, much work remains.

To evaluate its strategy for improving outcomes and to set goals for continuing improvement, an OTP must measure patient retention and monitor how it changes over time. Many OTPs cannot currently accomplish such measurements and will need to redesign their patient data systems to obtain and record all the necessary information on patient characteristics as well as the type and amount of treatment delivered to each. Many OTPs also will want to convert to a computerized patient information system to be able to analyze information easily and quickly. These are daunting organizational tasks that entail significant costs—both financial resources and staff time. Some State governments assist OTPs in their data acquisition and analysis, others do not. The research community could make an invaluable contribution by equipping agency and statewide data systems with the ability to perform survival analysis, the key statistical technique for measuring and comparing rates of retention (Magura et al., 1998).

Two other practical issues face OTPs preparing for programmatic change: lack of implementation manuals and lack of expertise in organizational change. The shortage of practical implementation manuals—for example, guidance for how to start up and run a take-home incentives program, including quality assurance guidelines—is a barrier to change but one the research community could address by ensuring creation and dissemination of such documents once an intervention has been validated in studies. Development of such materials should be one of the requirements for funding of research studies.

OTP managers have a wide range of experience and expertise and now face a sea change in expectations for the operation of their programs. Many could benefit from guidance on effective ways to prepare for and implement organizational change.1 For 30 years, OTPs have struggled to comply with multitudinous regulations and local laws (such as limits on dose levels, length of treatment, and take-home privileges), clinical practice constraints (for example, limited counseling sessions per patient per month), as well as internal policies and procedures growing out of the philosophies of administration and staff. This history has ingrained attitudes and responses among program managers and staffs that will require special effort to change. OTPs and their staffs—much like the patients they treat—approach the change process with different strengths and challenges (D’Aunno et al., 1999).

ADMINISTRATIVE DISCHARGE: TROUBLING ISSUES

As an OTP director, this writer could improve his agency’s retention rate with the stroke of a pen, by eliminating the possibility of administrative discharge (expulsion for cause) from treatment. Administrative discharge clearly lowers retention rates, but just as clearly is necessary in some cases. Moreover, while research and improved treatments may be able to provide standards for some types and causes of administrative discharge, others seem likely to remain matters of difficult—and ethically troubling—judgment.

Unremitting cocaine use by patients in OTPs is one of the most common causes of administrative discharge as well as dropout from treatment (Magura et al., 1998). Developing specialized, cost-effective therapies for cocaine-using methadone patients would help improve retention.

The most difficult administrative discharge decisions involve lack of response to treatment. While program rules often cite noncompliance rather than non-response as the reason for discharge, in effect they define what the program deems to be nonresponse. In an ideal world, there would be no need for such rules. OTPs would have the resources to take all who sought treatment and let patients continue indefinitely as long as they participated, even minimally, and did not impede the recovery of others. As things stand, however, with limited public funding and statutory caps on treatment “slots,” an OTP manager must weigh keeping a poorly responding patient in treatment against providing treatment access to someone else who might be able to benefit more from what the program offers.

In this environment, science can help clinicians make more informed decisions about who should stay and who should go. Currently, agency managers and the staff determine what constitutes nonresponse subjectively, from their clinical perspectives. OTPs would benefit enormously if research could provide ways to make these decisions objectively, by identifying signs—for example, levels of continuing drug use, absences from dosing and counseling sessions, lack of progress toward treatment goals—that continuing treatment will probably be fruitless. Such data would also help OTPs advocate for increased funding and treatment options, such as low-threshold treatment programs that provide options other than expulsion for lack of response. Research could also help OTPs by investigating how the presence of nonresponders affects the therapeutic environment for other patients—another concern that managers weigh when considering administrative discharges.

Clearly, for programs to be viable, some limits for acceptable behavior must be set and enforced. However, whether a particular behavior is unacceptable can be difficult to judge. OTPs generally concur that behaviors that threaten the safety of patients and staff and the status of the program in the community warrant expulsion, and they agree that violence or threats of violence against patients (on agency premises) or staff (on or off agency premises) and drug dealing fall into this category. Yet whether a particular act constitutes threatening behavior or drug dealing can be debatable. It is hard to imagine science lending any guidance to these judgments.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO CLINICAL COLLEAGUES

We stand at the threshold of a new era in the treatment of opioid addiction. Not only is methadone treatment changing, but new medications will soon be available for deployment in a variety of ways, not just in traditional clinic-based settings. We will be more accountable for outcomes than ever before. Patients, their families, our communities, and funding agencies will ask not whether opioid treatment is effective, but how well our patients do. Some of us will rise to the challenges of the new era and thrive; some won’t. In this writer’s opinion, three steps are critical:

-

Embrace change. We have to change both our thinking and our practices, beginning with a conversation between managers and staffs. Agency administrators will need to understand the new environment and engage their staffs in a dialogue about the reasons to change and methods of change and then explore together the perceived benefits and barriers to change. This means, in short, taking a fearless inventory of the strength and weaknesses of each agency.

In my own case, the inventory of my agency’s practices and assets revealed that our intake assessment form, developed some years earlier, was not going to be adequate. We switched to the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), a standardized assessment instrument (available free at www.tresearch.org/Assessment%20Inst/instruments.htm) that allows us to measure our retention rates and compare them to our past performance and to other programs using the ASI. The ASI also facilitates initial treatment plans that focus on patients’ needs for services in a variety of life domains, not just their drug addiction.

-

Focus on data. Read the literature about program factors that affect retention and outcome, and examine your agency practices in that light. Decide what data you need to collect for the ongoing program evaluation and quality assurance necessary to improve outcomes. Take the necessary steps to collect those data into a computerized database. Commit to a serious, ongoing allocation of agency resources for staff training and supervision.

In our agency, we have trained our intake counselors to gather the ASI information on all incoming patients and enter it in an electronic database that I then use in continuous program evaluation to examine patient characteristics, including their service needs, how those characteristics and needs change over time, and response to services. The cost to my agency was for staff training and acquisition of computers and the ASI software.

-

Partner with researchers. Reach out to the research community for help with decisionmaking on data acquisition and for ongoing data analysis. The collaboration will help you to better define and answer questions about how you can improve outcomes for your patients. All of us learned most, if not all, of what we know about clinical practices from listening to our patients. Think of program evaluation as a more systematic way of listening to your patients.

Through partnering with research colleagues to conduct studies at my agency, our staff has learned more about what kinds of behavioral interventions work with our patients, and clinical personnel are better able to apply those interventions. Participation in research has brought financial assets to my agency and allowed us to attract and retain very capable clinicians.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO RESEARCH COLLEAGUES

The new emphasis on program evaluation and quality assurance in OTPs affords a rare opportunity for collaboration between clinical practitioners and researchers interested in treatment improvement. This is the era when research-to-practice can really deliver on its heretofore unrealized promise. What is the research community to do to help make this happen? Here are four steps to accomplishing that goal:

Stop doing independent studies on the effectiveness of methadone treatment. If the new CSAT regulations work as designed, this country will have hundreds of OTPs systematically gathering data and evaluating their programs’ clinical outcomes. Partner with OTPs to design and conduct collaborative studies to refine the analysis of the treatment factors that we know contribute to retention and patient outcome and to identify additional treatment variables that affect outcomes. The power of the data being collected by OTPs will also allow analysis of gender-specific treatment variables that affect retention and outcomes.

Study cost-effectiveness. While studies have shown mixed results with respect to the amount of variance in patient outcomes attributable to program variables, OTPs want and need to know which program variables offer the best return on investment to improve outcomes. For example, given its financial constraints, should a program devote funds to more frequent urinalyses and incorporation of results in treatment planning, or should it spend that money on developing counselor competencies?

Develop implementation and quality assurance manuals. Using your experience as study designers and implementers, generate manuals to guide OTPs through the process of implementing state-of-the-art clinical interventions and practical self-evaluation protocols.

Develop “best practice” benchmarks for patient retention and outcomes. Help OTPs, their regulators, and funders understand what optimal clinical performance looks like so that they might measure program performance against those standards. This will require refining and applying the techniques, called case-mix adjustment, used in performance comparisons to make allowance for the fact that populations in some programs are more difficult to treat than others. Comparisons of outcomes made without taking into account the relative difficulties of treatment populations can lead to erroneous conclusions and unwarranted reactions, such as personnel actions or program funding cuts or decertification.

Footnotes

Readers interested in a guidebook for organizational change in addiction treatment programs could refer to The Change Book: A Blueprint for Technology Transfer, produced and distributed by the National ATTC, which can be reached at 1-877-652-2882 or www.nattc.org.

REFERENCES

- Blaney T, Craig RJ. Methadone maintenance: Does dose determine differences in outcome? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;16(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplehorn JRM, Lumley TS, Irwig L. Staff attitudes and retention of patients in methadone maintenance programs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;52(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, Silverman K, Stitzer ML. Use of methadone take-home contingencies with persistent opiate and cocaine abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;16(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condelli WS. Strategies for increasing retention in methadone programs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1993;25(2):143–147. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1993.10472244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aunno T, Folz-Murphy N, Lin X. Changes in methadone treatment practices: Results from a panel study, 1988–1995. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(4):681–699. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 21 CFR Part 291, 42 CFR Part 8. Opioid Drugs in Maintenance and Detoxification Treatment of Opiate Addiction; Final Rule. Federal Register. 2001;66(11):4075–4102. January 17, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Luckey JW. Implementation of the methadone treatment quality assurance system. Findings from the feasibility study. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2000;23(1):72–90. doi: 10.1177/01632780022034499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, Hubbard RL. Treatment predictors of tenure in methadone maintenance. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1991;3(1):73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux JF, Prihoda TJ, Vogtsberger KN. The relationship of methadone dose and other variables to outcomes of methadone maintenance. American Journal on Addiction. 1997;6(3):246–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Kang S, Demsky S. Program quality effects on patient outcomes during methadone maintenance: A study of 17 clinics. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34(9):1299–1324. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Demsky SY. Pre- and in-treatment predictors of retention in methadone treatment using survival analysis. Addiction. 1998;93(1):51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon AJ, et al. Pre-treatment characteristics, program philosophy, and level of ancillary services as predictors of methadone maintenance treatment outcome. Addiction. 1996;91(8):1197–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.918119711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Sells SB. Effectiveness of treatment for drug abuse: An overview of the DARP research program. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse. 1982;2:7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ward J, Mattick RP, Hall W. How Long Is Long Enough? Answers to Questions About the Duration of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. In: Ward J, Mattick RP, Hall W, editors. Methadone Maintenance Treatment and Other Opiate Replacement Therapies. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 305–336. [Google Scholar]