Abstract

Innovate and adapt are watchwords for substance abuse treatment programs in today’s environment of legislative mandates, effective new interventions, and competition. Organizations are having to evolve—ready or not—and those that are ready have superior chances for success and survival. The Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) survey is a free instrument, with supporting materials, that substance abuse treatment programs use to assess organizational traits that can facilitate or hinder efforts at transition. This article presents organizational change as a three-stage process of adopting, implementing, and routinizing new procedures; describes the use of the ORC; and outlines a step-by-step procedure for clearing away potential obstacles before setting forth on the road to improved practices and outcomes.

Under pressure to adopt evidence-based practices, substance abuse treatment programs are examining and implementing new procedures, policies, and clinical interventions in hopes of improving their effectiveness and efficiency (e.g., Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2000; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2004). Research and experience indicate that these programs will have to evolve through a complicated process of adaptation if they are to successfully institute new practices (Brown and Flynn, 2002). Each major step along the way—adopting, implementing, and routinizing the new practice—makes demands on an organization’s philosophy, resources, and capacities.

Like the patients they treat, programs attempting to change their ways must find within themselves sufficient motivation to sustain the change process (Backer, 1995). Leadership style, staff skills and relationships, resource availability, and internal and external pressures all affect an organization’s ability to change in the drug abuse treatment setting (Simpson and Brown, 2002; Simpson and Flynn, 2007a). Rogers (1995) has focused attention on distinctive categories of leadership and other factors in the context of technology transfer, highlighting the importance of “early adopters”—individuals and programs that actively seek new ideas and practices. A subtle but critical dynamic in the change process involves institutional atmosphere: a climate of vision, tolerance, and commitment is most conducive to efficient transitions. The greater the complexity and magnitude of a projected innovation, the more critical these factors are for success.

Ironically, substance abuse treatment programs faced with changing their organizational behaviors typically exhibit the same functional deficiencies they routinely address in their clients: lack of motivation, poor cognitive focus, and weak discipline. In such cases, where the organizational environment does not lend healthy support to the change process, complications multiply and prospects for success recede.

The Change Book (2004) of the national network of the Addiction Technology Transfer Center describes a comprehensive 10-step process for selecting, planning, implementing, and evaluating appropriate change strategies for drug treatment systems (www.nattc.org/resPubs/changeBook.html). The present paper describes the Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) instrument (Lehman, Greener, and Simpson, 2002), a tool for accomplishing Step 4 of that process: assessing the agency’s readiness to undertake significant change. The ORC materials are available without cost and are designed to be administered and interpreted by agencies themselves, without a need to hire consultants. Following a brief review of the change process, we outline the instrument’s properties and how to use it to identify and improve weak points of agency functioning in preparation for change initiatives. The ORC for community treatment providers can be accessed via a Web page created expressly for readers of this article: www.ibr.tcu.edu/info/spp.html. The Web page also includes all the related Texas Christian University (TCU) links that appear in the text below, along with pathways to other related materials that readers may find useful.

THE PATH TO CHANGE

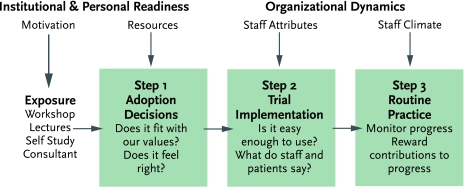

The body of research on technology transfer suggests that organizations typically change their practices in stages rather than as reflex responses to new information (Simpson, 2002; Simpson and Flynn, 2007b). In general, exposure to new information initiates a three-step action process that—if carried through to completion—culminates in the establishment of a revised routine practice (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Steps in program change and influences on adopting innovations (Simpson, 2002)

First, the organization must decide whether to adopt the new idea—that is, at the very least, to try it out. In making this choice, the organization weighs the innovation’s appeal to staff and leadership and its philosophical fit with their prevailing values. For instance, staff in substance abuse treatment programs that rely on a “medical” model to explain and treat addiction will likely differ from staff in programs that rely on a “12-step spiritual” model in their receptivity to certain interventions. Programs accordingly will find it useful to consider staff opinions about the preferred topics and methods for training, both of which are addressed in the TCU Survey of Program Training Needs (www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/Forms/ptn-s.pdf).

The second step in the change process is implementation of the innovation. User-friendly training manuals and workshops greatly facilitate this effort. Programs improve their chances of success by including sufficient time for participant practice and discussion, using flexible tools, fostering peer support networks, and planning for customized applications (Dansereau and Dees, 2002). Programs often begin implementation conditionally and continue only if they judge the innovation’s ease of use, the quality of available training, and the responses of clients and staff to be acceptable.

The ultimate step in instituting a new intervention or procedure is to move from trial use to routine practice. Programs generally will complete this step only if the benefits of the new procedure or intervention outweigh the costs for leadership, staff, and clients. The likelihood of meeting these criteria increases when an effective monitoring and rewards system exists for recognizing progress toward change. For example, Roman and Johnson (2002) found that, among 400 private drug treatment centers, those that had stronger leadership and had been in existence longer were more likely to use naltrexone to treat opiate and alcohol addiction. Proportionally higher caseload coverage by managed care was also a positive factor, representing a meaningful reward system for this medical innovation.

ASSESSING READINESS TO CHANGE

The ORC assessment measures organizational traits that research has shown significantly influence the ability to introduce new practices. The instrument has been specially tailored for the drug treatment and health services fields, and offers several alternative versions for specialized applications, including substance abuse treatment programs in communities and in correctional settings (www.ibr.tcu.edu/resources/rc-factsheets.html). The materials include scoring procedures and norms to help users interpret their results.

Medical, correctional, social, and behavioral health service delivery, as well as administrative/management organizations all can benefit from using the ORC. To select the appropriate version of the ORC and implement a workable sampling strategy, programs should develop a “utilization plan” based on their needs and rationale for conducting the assessment. In broadest terms, the primary uses for the instrument are to diagnose program functioning before adopting strategies for change and to evaluate changes over time.

The ORC instrument consists of 18 scales grouped into four sets for measuring staff perceptions about the adequacy of program resources, counselor attributes, work climate, and motivation or pressures for program changes (Table 1). The scales contain an average of six items apiece, each scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. On average, the ORC requires about 25 minutes to complete. In validation studies, principal components analysis confirmed the scales’ factor structure, coefficient alpha reliabilities showed they have adequate levels of psychometric internal consistency, and their relationships with selected indicators of client and program functioning yield good predictive validities (Lehman, Greener, and Simpson, 2002; Simpson and Flynn, 2007a).

TABLE 1.

The ORC’s Organizational Functioning Scales: What they measure

A. AGENCY NEEDS

|

B. INSTITUTIONAL RESOURCES

|

C. STAFF ATTRIBUTES

|

D. ORGANIZATIONAL CLIMATE

|

Source: Lehman, Greener, and Simpson, 2002.

The primary respondents to the ORC usually are the staff members in units that have direct service-related contact with clients—clinicians in substance abuse treatment programs. The ORC should be completed by staff in distinct organizational units or subunits—that is, individuals who work together, usually in a shared office complex, to achieve a common mission. To provide adequate group representation as well as to preserve personal anonymity, subunits should include no fewer than three respondents. Analyzing responses at the subunit level enables the organization to pinpoint the status and readiness to change of each of its separate functional components. In practice, it is common to find differing levels of resources, needs, and functioning among the various parts of an organization—whether they be individual programs in a statewide treatment network, different treatment centers in a single program, or individual subunits of a single treatment center, such as outreach, detoxification, and residential divisions.

Guidelines for Administration

A data management team, which may be either internal or external to the organization being assessed, conducts the survey. Making it plain to all staff that the team has full authority for this activity and delineating clear survey procedures help to ensure cooperation. An administration-ready copy of the ORC instrument for community treatment staff, along with survey scoring guides and related psychometric resources, can be downloaded from the Internet and used without charge (www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/Forms/orc-s.pdf). Because respondents take the survey anonymously, the survey instrument includes an optional two-page introductory section with questions about the respondent’s characteristics and work location. This information can be crucial for comparing results across units and interpreting differences.

Advance explanation of the purpose for the ORC survey from the organizational leadership sets the stage for obtaining maximum response rates. To ensure frank, accurate survey responses, administrators must attend carefully to details of the assessment process, especially regarding voluntary participation and protection of confidentiality. They should (1) provide staff with adequate time and a private setting to complete the survey; (2) clarify that the survey is confidential (using “informed consent” procedures when applicable); (3) establish a simple method for returning completed surveys that preserves privacy, such as submission in unsigned, sealed envelopes; (4) give details of the “who, when, and where” of the data collection and scoring procedures to be followed; and (5) state how and when feedback of survey results will be provided and how they will be used. Surveys should be completed in an individual’s work space or in a group setting, during the same time frame, and without distractions or interruptions.

Scoring and Interpretation

The ORC for community programs is the original and most commonly used assessment. The ORC-S Scoring Guide (www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/Forms/orc-s-sg.pdf) explains procedures for computing scores. Scoring is essentially simple, the only complication being that while most item response ranges run from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement), a few run the other way and need to be weighted in reverse. To obtain the scale score for a program or organizational unit, all unit members’ responses to the items comprising the scale are pooled, averaged, and multiplied by 10, yielding a number from 10 to 50.

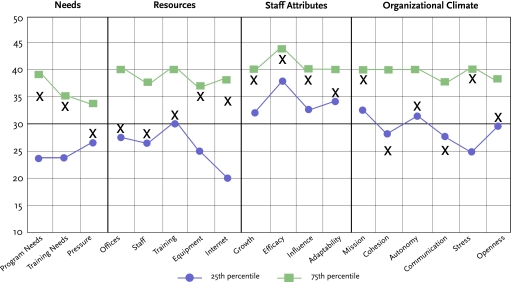

A hypothetical Counselor Group A’s scale scores are charted in Figure 2, visually displaying the group’s functioning profile. Along with the group’s scores, plotted as a series of Xs, the chart contains 25th and 75th percentile norms, which have been calculated using 2,031 completed surveys from our previous research. These norms aid interpretation; organizations can evaluate their staffs’ responses not only in terms of how far they fall above or below 30—the neutral point of neither agreement nor disagreement with the content of a scale—but also how they compare with the responses of other organizational units that have completed the ORC.

FIGURE 2. Counselor Group A’s initial ORC results.

Counselor Group A’s result on each of the 18 ORC scales is shown by an “X.” For comparison and interpretation, the 25th and 75th percentile scores (or norms) for each scale are also shown, based on more than 2,000 similar surveys conducted at other organizations.

Agency Needs: In general, Counselor Group A viewed their agency’s needs to be moderate; scores for Program Needs, Training Needs, and pressure to change all fell between the 25th and 75th percentile norms. A review of responses to specific items of the Program Needs and Training Needs scales (not shown) revealed that the scores on both reflect staff concerns about ensuring the adequacy of measures for client performance and progress, increasing treatment participation by clients, and improving client thinking and problem-solving skills. The counselors rated pressures for change near the 25th percentile norm, suggesting that they attribute a low level of urgency to these needs.

Resources: Ratings of the adequacy of Offices, Staff, Training, Equipment, and Computer/Internet access averaged between 28 and 35. Offices, Staff, and Training received the lowest ratings (29, 28, and 32), all three of which were near the 25th percentile for these scales. On the other hand, Equipment and Internet access ratings were very favorable (35 and 34), close to the 75th percentile norms.

Staff Attributes: The group’s scores indicate overall confidence in their professional abilities and performance. Those for growth, personal efficacy, and mutual influence all fell close to the 75th percentile norm. Adaptability had a lower score, closer to the 25th percentile norm.

Organizational Climate: Although the group registered a sense of clarity about its mission, other indicators suggest significant problems in the area of organizational climate. The group’s scores for Cohesion and Communication (25) were the lowest given to any scale in the survey, and they fell below the 25th percentile norms. Autonomy and Openness to Change were rated marginally above the midpoint (32 and 31, respectively), and these scores likewise were comparatively poor as indicated by their proximity to the 25th percentile. Finally, Stress levels were high as judged by both the high agreement score value (38) and its proximity to the 75th percentile.

Summary: Counselor Group A’s survey results strongly indicate problems in the organizational atmosphere, in particular with staff relationships, communications, and stress. The agency might reasonably conclude that addressing these areas first will bring the most rapid improvement in its functioning and readiness for change. The counselors also see moderate needs to improve training and agency performance in the areas of client assessments, participation, and cognitive functioning, while feeling little organizational pressure to make such changes. Offices, staff capacity, and training resources represent areas of modest need. The counselors’ high level of confidence in their skills is a positive finding, as is their assessment that the agency’s technical equipment is adequate.

An initial interpretation of Counselor Group A’s results would first note poor scores on the Organizational Climate scales. Mission appears to be well defined for staff, but the counselors ranked Cohesion and Communication lowest of all the scales on the ORC, both well below the 25th percentile norm. As well, Autonomy and Openness to Change both fall very near the 25th percentile norm, and Stress is near the 75th percentile norm.

The program’s main source of concern going forward will be the Organizational Climate scores. Although scores in the other scale groupings all fall within the 25th–75th percentile norms, potential barriers to change appear as well in the Needs and Resources scales. In the Needs grouping, by giving Program Needs and Training Needs relatively high ratings—close to the 75th percentile level—the counselors have indicated that they see shortcomings in these areas; similarly, their rating of Pressure to Change, being below 30, suggests complacency. Of the Resources scales, the counselors ranked Offices and Staff below the neutral score of 30, and Training below the middle of the normal 25th–75th percentile range. In contrast, hardware resources seem to be adequate, based on high Equipment and Internet scale scores, and the Staff Attributes rating indicates an overall positive level of self-confidence.

Altogether, Counselor Group A’s profile evinces poor organizational climate, high needs, and low resources. As things stand, efforts to engage Counselor Group A in innovating clinical enhancements to program services are unlikely to proceed smoothly.

FROM RESULTS TO ACTION PLANS

The initial step in moving from ORC assessment to action is to summarize the results for staff, encouraging buy-in, soliciting feedback and suggestions, and preparing staff for possible future actions. The presentation should be brief, nontechnical, and nonstatistical, with graphics or tabulations to help explain major points.

When several treatment programs have filled out the ORC survey as part of a large-scale effort, such as a statewide workshop for transferring research to practice, an economical means of communicating the findings is to assemble key participants for a formal presentation. Sample slide presentations from feedback workshops illustrate the diversity of treatment programs (www.ibr.tcu.edu/presentations/rtp-NFATTC.pps; www.ibr.tcu.edu/presentations/rtp-PrATTC.pps).

As detailed ORC findings often are of interest primarily to program leaders, an alternative way to give the results to staff is in the form of a brief one- to three-page general overview highlighting major areas of strength and concern. Such reports, covering the results from a single organizational unit, also can serve as “personalized” feedback to those units following a general workshop presentation.

To help program leaders and staff use ORC assessment information systematically, we have published a procedural guide called Mapping Organizational Change (MOC)(www.ibr.tcu.edu/_private/manuals/BriefInterventions/BI(06Jun)-MOC.pdf). The MOC includes a set of interrelated “fill-in-the-blank” charts to be completed by individuals or in small break-out discussion groups. Such heuristic displays have been shown to facilitate communication, group focus, and memory in education (Dansereau, 1995), business (Newbern and Dansereau, 1995), and counseling (Dansereau and Dees, 2002). The choice of staff to participate in this change- planning process is flexible; each group that has participated in the survey can meet as a whole, or a team of group leaders may be selected to serve as representatives.

The MOC serves as a discussion guide for addressing three major issues: goal selection, planning, and commitment to action. Program leaders need to identify and prioritize goals, taking into account the likely benefits, costs, and resources, as well as potential problems and solutions, associated with achieving them. Following goal selection, the MOC provides for setting specific subgoals, along with a sequence of detailed action and implementation plans.

The process of goal selection and planning usually is initiated by the chief administrator and/or selected higher level staff who serve as the equivalent of early adopters within an organization. However, effecting change depends on the capacity and willingness to comply of workers throughout an organization. Consequently, leadership should encourage a common view of organizational goals, problems, and solutions—and assure staff of their own and the organization’s ability to create change.

Besides laying out a systematic process for planning organizational changes, the MOC provides a paper trail of the evolution of thinking about the action plan. It can serve as an outline to inform staff of the logic underlying an innovative change. A good fit between the innovation and staff values is needed to facilitate buy-in (Klein and Sorra, 1996). The MOC can improve interactions with accrediting and auditing agencies by illustrating past efforts and future plans. Finally, it can be used recursively at multiple levels of the organization. For example, using similar graphics, the steps can be tailored to help counselors develop treatment plans for clients as well as to help supervisors modify counselor behaviors.

Counselor Group A in Transition

To return to our hypothetical example, after analyzing the ORC results from Counselor Group A, its parent program hired a new clinical director. This individual quickly implemented new management styles and procedures. Program leadership met with Counselor Group A to review its ORC profile and develop an action plan. The outcome of these discussions was that the counselors focused on three areas of concern, which are listed on the MOC “Select Goals” map (see “Counselor Group A’s goal-setting process”): Cohesion, Communication, and Stress. Of these, the group chose “improve the way changes are communicated” as their key topic and identified the subgoal “make messages clearer,” as a starting point for subsequent actions.

Over the next year, Counselor Group A proceeded in a structured way to initiate the proposed actions, evaluate progress, and move on to other subgoals, with the ultimate objective of readying themselves to implement clinical changes. The group took the ORC assessment twice more during this interval, each time repeating the MOC process to see if problem areas had been ameliorated and to fix new interim goals. As they gained experience and confidence, their motivation and receptivity to new ideas improved and the group was able to tackle multiple goals simultaneously.

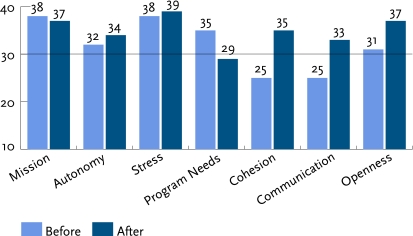

One year later, Counselor Group A repeated the ORC again. Figure 3 compares the results of this survey with those of their original ORC. The three bar graphs in the left half of Figure 3 indicate that moderate to high agreement on having a clear mission and autonomy, along with high job stress, remained unchanged. However, the four measures in the right half of Figure 3 show highly significant, 6- to 10-point improvements in ratings for Program Needs, Staff Cohesion, Communication, and Openness to Change. Thus, while staff pressures and perceived mission remained stable over time, executive controls and information sharing shifted. Perceptions of program needs diminished as communication channels opened up and staff gained more support in doing their jobs.

FIGURE 3.

Counselor Group A’s ORC scores before and after program changes

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Drug abuse treatment networks and programs require strong, flexible, efficient organizational functioning to successfully respond to the growing demand for evidence-based practices. Although attention usually centers on counselors’ responses to new clinical procedures, translating drug abuse science into practice actually entails a complex process involving overlapping clinical and organizational systems.

The ORC assessment instrument is the product of broad research aimed at analyzing change dynamics into discrete stages that can be measured and addressed through initiatives with well-defined, reachable goals (Simpson, 2002, 2004). To date, we have research-based and advisory experiences with the administration of more than 4,000 ORC surveys in more than 650 organizations in the United States, Italy, and England. Considering the wide variations in structure, purpose, and locations of these agencies, they have proven to be surprisingly similar in the ORC profiles and interpretations.

Treatment research also has shown a direct relationship between the quality of organizational functioning and clients’ performance in treatment (Lehman, Greener, and Simpson, 2002; Simpson and Flynn, 2007a). Although not addressed in detail in this paper, one tool for monitoring client functioning (individually and collectively) is the TCU Client Evaluation of Self and Treatment (CEST) assessment. Structured similarly to the ORC, the CEST includes scales to measure motivation, psychological and social functioning, therapeutic engagement, and social support (www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/Forms/cest.pdf; see Joe et al., 2002). When used in conjunction with the ORC, the CEST can provide a more complete picture of the organization and its clinical performance (see Simpson, 2006).

Organizations, like individuals, need to change and naturally resist doing so. For substance abuse programs, as for the clients they treat, candid self-assessment of motivations, strengths, and weaknesses is a prerequisite for attaining the benefits of better functioning. The ORC has been designed to facilitate such self-assessment and has been extensively validated. Used in conjunction with other tools, such as the MOC and the CEST, the ORC can help programs meet the challenges and reap the benefits of today’s rapidly evolving substance abuse treatment environment.

Counselor Group A’s goal-setting process.

STEP 1: SELECT GOALS

Select a general goal

Based on Counselor Group A’s ORC profile, the areas most needing improvement to facilitate change readiness are staff cohesion, communication, and stress. As poor communication impedes cohesion and creates stress, improving communication may bring improvements in all three areas and is a reasonable first general goal. The group’s decision pathway from identifying this general goal to selecting a single first principle of action follows.

Identify specific goals that will promote the general goal

State specific problems contributing to the situation needing improvement

There is always much confusion when policies and procedures change.

Everybody is not on the same page; some people don’t know what’s going on.

Identify specific objectives that will contribute to alleviating the problems

Improve the way changes are communicated.

Get everyone moving down the same path.

Select one initial objective

Counselor Group A chose to focus on improving communication first, reasoning that this was key to their ultimate objective of enhanced change readiness.

Identify potential subgoals that will promote the specific goal

Make messages clearer.

Deliver messages in a timely manner.

Select a single subgoal to pursue first

Counselor Group A opted to focus first on making messages clearer and then turn to timeliness, figuring that prompt notification is effective only if messages are clear.

STEP 2: PLAN

Identify resources for achieving the goal and ways to utilize them

Resources

Some staff members know how to make maps and charts.

Utilization plan

Draw on skilled staff to promote communication efforts and to train colleagues as necessary.

Identify potential obstacles and possible responses

Potential problem

Stakeholders create unreasonable deadlines.

Response

Establish a special alert system for urgent messages.

STEP 3: TAKE ACTION

Initiate well-defined activities with specific start dates and, where appropriate, target dates for completion

Activity #1

Train one or more staff to create clear, interesting, and memorable messages using graphics, etc. Start 8/1/05; complete 9/15/05.

Activity #2

Initiate a procedure whereby message-trained people create and edit important messages. Start 10/1/05; ongoing, no end date.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIDA grant number R37DA13093. Dr. Simpson’s work in developing the concepts and materials described in this article began in 1989 with support from NIDA grant number R01DA06162.

REFERENCES

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network. The Change Book: A Blueprint for Technology Transfer. Kansas City, MO: ATTC National Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE. Assessing and enhancing readiness for change: Implications for technology transfer. In: Backer TE, David SL, Soucy G, editors. Reviewing the Behavioral Science Knowledge Base on Technology Transfer. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. (NIDA Research Monograph 155, NIH Publication No. 95-4035) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, Flynn PM. The federal role in drug abuse technology transfer: A history and perspective. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):245–257. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. The National Treatment Improvement Plan Initiative (DHHS Publication No. SMA 00-3479) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2000. Changing the conversation: Improving substance abuse treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau DF. Derived structural schemas and the transfer of knowledge. In: McKeough A, Lupart J, Marini A, editors. Teaching for Transfer: Fostering Generalization in Learning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1995. pp. 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau DF, Dees SM. Mapping training: The transfer of a cognitive technology for improving counseling. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, et al. Measuring patient attributes and engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Academy of Management Review. 1996;21(4):1055–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Blue Ribbon Task Force on NIDA Health Services Research. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newbern D, Dansereau DF. Knowledge maps for knowledge management. In: Wiig K, editor. Knowledge Management Methods. Arlington, TX: Schema Press; 1995. pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Johnson JA. Adoption and implementation of new technologies in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for drug treatment process and outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(2):99–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. A plan for planning treatment. Counselor: A Magazine for Addiction Professionals. 2006;7(4):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Brown BS, editors. Special Issue: Transferring research to practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4) doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Flynn PM, editors. Organizational Readiness for Change (Special Issue) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007a doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving innovations into treatment: A stage-based approach to program change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007b doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.023. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]