Abstract

Strong gain-of-function mutations have not been identified in humans in the FSH receptor (FSHR), whereas such mutations are common among many other G protein-coupled receptors. In order to predict consequences of such mutations on humans, we first identified constitutively activated mutants of the mouse (m) Fshr and then expressed them under the human anti-Müllerian hormone promoter in transgenic mice or created knock-in mutation into the mouse genome. We show here that mutations of Asp580 in the mFSHR significantly increase the basal receptor activity. D580H and D580Y mutations of mFSHR bind FSH, but the activity of the former is neither ligand-dependent nor promiscuous towards LH/human choriogonadotropin stimulation. Transgenic expression of mFshrD580H in granulosa cells leads to abnormal ovarian structure and function in the form of hemorrhagic cysts, accelerated loss of small follicles, augmented granulosa cell proliferation, increased estradiol biosynthesis, and occasional luteinized unruptured follicles or teratomas. The most affected mFshrD580H females are infertile with disturbed estrous cycle and decreased gonadotropin and increased prolactin levels. Increased estradiol and prolactin apparently underlie the enhanced development of the mammary glands, adenomatous pituitary growth, and lipofuscin accumulation in the adrenal gland. The influence of the mFSHRD580Y mutation is milder, mainly causing hemorrhagic cysts in transgenic mFSHRD580Y and mFSHRD580Y -knock-in mice. The results demonstrate that gain-of-function mutations of the FSHR in mice bring about distinct and clear changes in ovarian function, informative in the search of similar mutations in humans.

Constitutively active mutations of FSH receptor in female mice induce multiple ovarian and nongonadal abnormalities including infertility and tumors.

The gonadotropins FSH and LH are essential regulators of ovarian endocrine function and female fertility, and lack of either hormone or inactivation of the cognate receptors results in hypogonadism, arrested follicular maturation, and primary ovarian failure (1,2,3). The glycoprotein hormones act via their G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the FSH receptor (FSHR) being mainly expressed in ovarian granulosa cells and in testicular Sertoli cells (4,5). The circulating levels of gonadotropins, and number of their gonadal receptors, are strictly regulated during menstrual and estrous cycles, and therefore excessive gonadotropin action can lead to endocrine dysfunction. For example, rare patients with FSH-secreting pituitary adenomas suffer from ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (6,7,8), and constitutively active mutants (CAMs) of the human LH (hLH)/choriogonadotropin (CG) receptor (hLHCGR) in males cause early-onset gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty (9).

Only a few cases of genetically deviant hFSHR activation have so far been reported; a hypophysectomised man carrying an Asp567Gly mutation was shown to have normal semen parameters after testosterone replacement therapy but without FSH supplementation, suggesting that the mutated hFSHR is spontaneously active in the absence of ligand (10). In addition, substitutions of Thr449, Ile545, and Asp567 lead to variable increases in constitutive receptor activity, but more importantly, they allow the hFSHR to be more readily activated by high concentrations of the other glycoprotein hormones (11,12,13,14,15). Female heterozygous carriers of such mutations develop OHSS during pregnancy, when the hFSHR is promiscuously activated by high concentration of hCG. Also the carriers of the Ser128Tyr mutation develop pregnancy-induced OHSS, but without association with increased constitutive receptor activation, suggesting that it is not required for the development of disease (16).

Strong constitutively activating mutations of hFSHR have not yet been found in humans. Possible explanations are that such mutations do not cause detectable phenotypes or that the phenotype is unexpected. This prompted us to create mouse models with a strongly activating mFSHR mutation. It was expected that assessment of phenotype of such mice would help us to predict suitable human candidates for the search of activating hFSHR mutations. For that purpose, Asp580 [D6.44 according to Ballesteros and Weinstein numbering (17)] of mFSHR was replaced with Gly, Glu, Tyr, or His, and functions of the mFSHR variants were analyzed. D6.44 is known to be a hotspot for activating mutations in the other glycoprotein hormone receptors, i.e. hLHCGR and human thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (hTSHR) (9,18). We show here that mFSHRD580H in particular increases constitutive cAMP production and that expression of the constitutively active receptor leads to severe endocrine disturbances in the female.

Materials and Methods

Hormones

Recombinant human (rh) FSH, LH, and CG were gifts from Organon (Oss, The Netherlands).

Plasmid constructs and generation of transgenic (tg) and knock-in mice

The nucleotide substitutions leading to mutations Asp580Gly, Asp580Glu, Asp580Tyr, and Asp580His were introduced into the wild-type (WT) (cDNA) mouse Fshr [Acc AF095642 (19)] in pSG-5 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and pcDNA3.1(−) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), where the cytomegalovirus promoter had been replaced with the human anti-Müllerian hormone (hAMH) promoter. The constructs were used for characterization of the mFSHR variants and furthermore for pronucleus microinjection and generation of tg mFshrD580H [FVB/N-Tg(AMH-FSHRD580H)/IC], mFshrD580Y [FVB/N-Tg(AMH-FSHRD580Y)/IC], and mFshr-wt [FVB/N-Tg(AMH-FSHR)/IC] mouse lines. The sublines with highest transgene expression and most intense phenotype upon preliminary screening, mFshrD580H/4 and -14, mFshrD580Y/5 and -11, and mFshr-wt/27, were used for more detailed analyses. However, for the quantitative analyses such as RNA expression and hormone measurements, only mice from single sublines, mFshrD580H/14 and mFshrD580Y/5, were used. In the second approach, the nucleotide substitution leading to mutation Asp580Tyr was introduced into a fragment of mFshr bacterial artificial chromosome clone, and mFshrD580Y-knock in (ki) (B6;129-FshrD580Y/IC) mice were generated by blastocyst injections of targeted embryonic stem cells. For oligonucleotide sequences, construct schemes, and further details, see Supplemental Materials and Methods, Supplemental Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1 published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Cells, transfections, and luciferase and cAMP assays

For luciferase activity assays human embryonic kidney 293H (Invitrogen) and mouse Sertoli SMAT1 cells (20) were transiently transfected with WT or mutated mFshr constructs, cAMP-response element reporter gene plasmid [pADneo2 C6-BGL (21)], and transfection efficiency control plasmid pRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI), and in case of ligand stimulation, they were treated with rhFSH, rhLH, or rhCG on the following day. For cAMP measurements, the cells were transfected with the mFshr constructs and stimulated with increasing concentrations of rhFSH. All reporter gene and cAMP assays were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice. The results were presented per binding capacity of each receptor variant that was measured as described before (22). For details, see Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Animal husbandry and sample collection

All procedures with mice were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for the University of Turku and Imperial College London. Animal studies were performed under a Project License issued by the United Kingdom Home Office. For analyzing the onset of puberty, females were examined daily for vaginal opening from d 22 postpartum. For testing fertility, the 3-month-old female tg and WT mice were bred with at least two WT FVB/N males for at least 5 months. The estrous cycle was determined by analyzing the vaginal smear for 20 d at the age of 10 wk and/or after the breeding test. Smear samples were collected at 0900–1000 h, stained by the Giemsa method, and defined as proestrus, estrus, metestrus 1–2, and diestrus as described (23). Serum and tissue samples were collected and processed using standard protocols. For details, see Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR

For quantitative transgene and target gene expression analyses, total RNA was isolated from tissues by the silica-based membrane system (RNeasy Micro/Mini kit; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). cDNA was generated from DNase I-treated RNA samples with Superscript* First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen). RT-PCR analyses were performed using SYBR* Green Quantitative RT-PCR system (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with MJ Opticon Analyzer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Standard curves were generated from dilution series of the plasmids containing the amplified area, and the copy number for each amplicon was calculated. Final results were calculated as copy number percentage from mRpl7 copy number. Primers and conditions used are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Estimation of follicle numbers

The right-side ovary of four tg and four WT animals was collected into Bouin’s fixative. After fixation for 4–6 h, the samples were dehydrated, embedded into paraffin, and cut thoroughly into sections of 8-μm thickness, followed by staining with Harris’ hematoxylin and eosin. Follicle counting was performed with an unbiased stereological method using a physical detector without counting frames (24). Every 12th pair of adjacent sections was sampled, starting at a random section with the first 11. In each pair the first section was the “look-up” section and the second was the reference. Only follicles with an oocyte nucleus in the reference section, but not the look-up section, were counted. The total number of follicles seen was then multiplied by 12. The process was then reversed with the look-up section becoming the reference section and vice versa. Follicles were classified according to the classification of Stubbs et al. (25). Ki67 immunostaining and counting of Ki67-positive follicles were carried out as in Ref. 26.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA or Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

mFSHR variants activate the cAMP pathway but do not change the ligand specificity of receptor activation

To identify the mutations leading to constitutively active mFSHR, Asp580 was replaced with Gly, Asn, His, and Tyr; the corresponding position is a hotspot for activating mutations in LHCGR (9) and TSHR (18), and its modification to Gly in a rat/human FSHR chimera increases the basal activity of the receptor (27). In transiently transfected human embryonic kidney 293H and mouse Sertoli SMAT1 cells, the mFSHRD580Y and mFSHRD580H variants were most effective in increasing the basal cAMP and its response, typically 4- and more than 10-fold, respectively (Fig. 1A). The mutations enhanced the cAMP responses similarly in the two cell lines, and the results were independent of the type of promoter used, Simian virus 40 or hAMH (data not shown). Stimulation of mFSHR variants D580G, D580Y, and D580E with FSH resulted in modest increases in receptor activation, which did not reach the maximal activation attained by the WT receptor, whereas the high activity of the mFSHRD580H variant was FSH-independent (Fig. 1B). cAMP responses of the receptor variants D580Y (Fig. 1C), −D580G, and −D580E (data not shown) were modestly increased at very high concentration (50 IU/ml) of human hCG and LH, but less than that of the WT receptor, whereas the response of mFSHRD580H was again unaffected by the stimulations (Fig. 1C). Thus, the modifications of mFSHR at position 580 did not affect its ligand specificity with respect to activation.

Figure 1.

A, Signaling activity of the mFSHR variants in vitro as measured by their cAMP responses, i.e. cre-luciferase reporter gene activation, and adjusted for their ligand binding capacity without hormonal stimulation. B, cAMP response of the mFSHR variants after stimulation with FSH. C, Activation of the mFSHR variants by LH and hCG. Open bars in all panels depict reporter gene activation without ligand stimulation. Filled bars in panel B depict (from left to right) the response to 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 IU/liter FSH stimulation. Light and dark gray bars in panel C depict (left to right) stimulations with 0.05, 5, and 50 IU/ml of hCG and LH, respectively. The pSG-5 mock-transfected samples were stimulated with the highest concentrations of hCG and LH. RLU, relative luciferase units (luciferase activity/renilla luciferase activity). Bars, average + sd of triplicates. The data represent typical results from at least three independent experiments.

Generation of mice expressing mFSHRD580H and mFSHRD580Y and knock-in for mFSHRD580Y

Based on results obtained from in vitro analysis of the mFSHR variants, mFSHRD580H and −D580Y mutants were chosen to be introduced into the mouse genome and to be expressed under the hAMH promoter. To control for possible effects of mFSHR overexpression, also a mouse line with WT (cDNA) mFshr was generated. Microinjections resulted in five independent mFshrD580H and 6 mFshrD580Y mouse lines all expressing the transgenes in the ovaries and testes, whereas two out of six mFshr-wt sublines showed gonadal expression (data not shown). In addition, introduction of the mutation D580Y into the endogenous mFshr generated an mFshrD580Y-ki line showing germ line transmission.

The transgene transmission of the AMH promoter-driven lines, and the germ line transmission of mFshrD580Y-ki line, closely followed Mendelian distribution (Supplemental Table 3). The mFshrD580H females demonstrating the clearest phenotypes upon preliminary screening were studied in greatest detail. The (mRNA) mFshrD580H concentration varied in the ovaries of 6- to 8-month-old mice from 0.2 to 9.7% of that of the housekeeping gene mouse riboprotein L7 (mRpl7) (average ± sem being 3.03 ± 0.72), whereas the highest concomitant expression of the endogenous mFshr was 6.9%. Hence, the expression level of the transgene was similar to that of the endogenous mFshr.

Expression of mFshrD580H increases the frequency of irregular estrous cycles and affects fertility

Transgene expression did not have obvious effects on the development of mFshrD580H female mice such as timing of vaginal opening and urogenital distance (for more details, see Supplemental Results and Supplemental Table 4). Instead, irregular estrous cycles were detected in 63% (10/16) of the mFshrD580H females, more than or equal to 10 wk at age, vs. 17% (1/6) of the WT controls (Supplemental Table 5). Whereas estrous cycles of the rest of the mFshrD580H females followed that of the WT littermates, the cycles of the affected mice missed proestrous and estrous phases (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fertility of the tg mice with regular estrous cycles was not compromised. Interestingly, their litter sizes were larger than those of WT females [8.7 ± 2.1 (average ± sd) for WT and 11.3 ± 1.2 for tg, P < 0.05; Supplemental Table 5]. Conversely, seven of 10 acyclic tg mice either showed no signs of pregnancy and delivered no litters, and the rest of them presented with a delay in the time to first pregnancy (Supplemental Table 5). Despite disturbed estrous cycles, follicles from primordial to antral stage, and corpora lutea, were present in the mFshrD580H ovaries (Fig. 2), even in the aging mice having failed fertility test (Fig. 2G), suggesting on-going follicular maturation up to ovulation and luteinization. Occasionally, however, luteinized unruptured follicles were perceived (Fig. 2H, inset i) indicating unsuccessful ovulations.

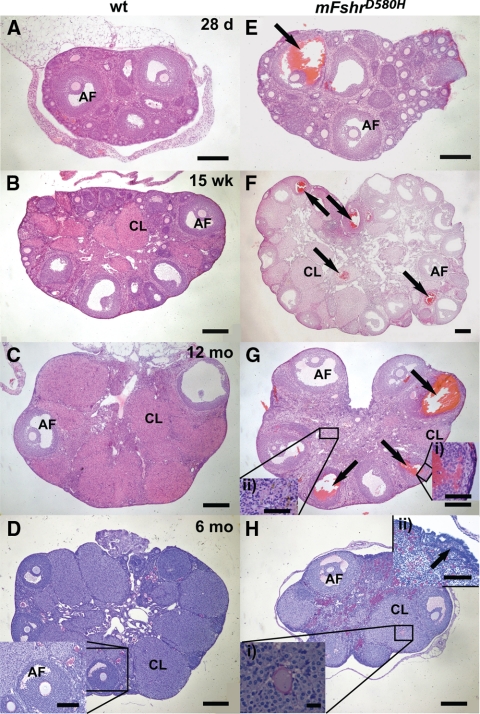

Figure 2.

Gross histology of ovaries in WT (A–C) and mFshrD580H (E–G) females at the age of 28 d (A and E), 15 wk (B and F), and 12 months (C and G) and PAS staining of an ovary of 6-month-old WT (D) and tg (H) mice. Hemorrhagic cysts are common in the ovaries of the tg mice (E–G, arrows) showing leakage of blood cells from the thecal layer into the antrum (G, inset i). Multiple simultaneously maturing antral follicles increase the size of the tg ovaries (F). In most of the old mice, large follicles are maturing, but stroma is occupied by interstitial hyperplasia (G, inset ii, and H). Minor staining with PAS is seen in the ovaries of WT mice, in which mainly zonae pellucidae and oocyte remnants present with the stain (D, inset), but in the ovaries of mFshrD580H mice, the stroma is broadly stained with PAS (H, inset ii). The oocyte in the unruptured luteinized follicle is also encircled by PAS-positive zona pellucida (H, inset i), and the surface epithelium has thickened adjacent to the PAS-stained areas (H, inset ii, arrow). AF, antral follicle; CL, corpus luteum. Scale bars, Main frames, 200 μm; D, inset, and H, inset ii, 100 μm; G, inset, 50 μm; H, inset i, 20 μm. D and H, Blue staining, nuclei; purple staining, PAS-positive glycogen.

Ovaries of adult tg mice demonstrate several structural and functional abnormalities with increasing severity upon aging

At macroscopic and microscopic levels, the main sign of CAM mFSHR was the development of hemorrhagic follicles in ovaries of the mFshrD580H females (Fig. 2, E–G, arrows). The first hemorrhagic cysts were visible at 28 d of age (Fig. 2E), and they were found in most of the elderly tg females, red blood cells infiltrating through the theca cell layer (Fig. 2G, inset i, and Supplemental Table 6). Similar hemorrhagic cysts developed also in 29% of the mFshrD580Y mice at the age of 1 yr. They were abundant also in heterozygous and homozygous mFshrD580Y-ki mice from the age of 2.5 months onwards (Supplemental Table 6). Instead, they were rare in WT littermates of all the tg lines as well as in the tg line expressing WT mFshr.

Glycogen-rich, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained interstitial cell hyperplasia with multinuclear cells was apparent in the ovaries of 6-month-old mFshrD580H mice (Fig. 2H), and in 1-yr-old mice, they covered most of the stroma (Supplemental Fig. 3). In WT ovaries, only few cells were PAS-positive, glycogen-rich zona pellucida and remnants of oocytes from atretic follicles being the major regions intensely stained by PAS (Fig. 2D, inset), and minor areas with interstitial cell hyperplasia were seen upon aging. Worthy of note, the surface epithelium was unusually thick close to the PAS-stained areas with cellular mesenchyme underneath (Fig. 2H, inset ii).

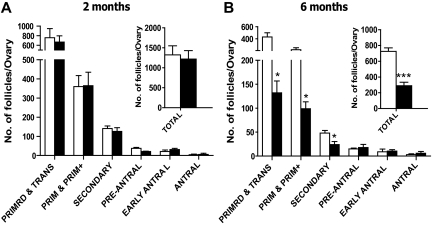

Maturation of the follicles and corpora lutea continued in the aging tg mice (Fig. 2, G and H), but their total follicle number declined faster than in WT females. At 8 wk of age, there was no difference in the number of any type of follicles between the mFshrD580H and WT females, but the reduced number of primordial, primary, and secondary follicles in the tg ovaries was evident at the age of 6 months (Fig. 3, A and B). The significantly higher proportion of Ki67-positive small follicles in tg than in WT females (Table 1) suggested that the transgene expression increased proliferation of the granulosa cells and growth of primary follicles. The numbers of preantral, early antral, and antral follicles remained similar in the mFshrD580H and WT mice, showing that despite the declining pool of small follicles in the tg mice, follicles were recruited to FSH/FSHR-dependent maturation as in WT mice. Expression of (mRNA) mAmh in the ovaries of 6-month-old mice suggested that there were two groups of the tg mice; those with high tg expression and low (mRNA) mAmh expression implying decline in the amount of recruited follicles, and those with high (mRNA) mAmh suggesting persistently high number of follicles available for recruitment (Supplemental Fig. 4). In the latter group, the (mRNA) mAmh concentrations were in general higher than in WT littermates (Supplemental Fig. 4). The other abnormalities in the tg ovary such as PAS-stained hyperplasia, thickening of the surface epithelium, and loss of follicles, also correlated with ovarian tg expression (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Classification and numbers of ovarian follicles of 2-month-old (A) and 6-month-old (B) WT and mFshrD580H mice reveal accelerated loss of small follicles at age of 6 months in the latter. The bars represent average + sem of four independent samples. Open bars, WT; filled bars, tg mice; primrd & trans, primordial and transition; prim & prim+, primary and primary plus; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.005.

Table 1.

Proportion of small ovarian follicles positive for Ki67 immunostaining in WT and mFSHR-D580H sections

| Follicle type Line | Primordial and transitional

|

Primary

|

Primary+

|

Secondary

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amounta | % | Amounta | % | Amounta | % | Amounta | % | |

| WT | 0/91 | 0 | 24/136 | 17.6 | 46/73 | 63.0 | 116/135 | 85.9 |

| mFshrD580H | 0/25 | 0 | 43/89b | 48.3 | 74/82b | 90.2 | 92/101 | 91.1 |

Number of Ki67 positive follicles per number of all follicles in the group. Follicles were counted altogether from 58 sections from five tg animals and their four WT littermates. Follicles with one or more Ki67 positive granulosa cell were considered as positive ones. The numbers do not represent the total follicle number, but proportion of Ki67 positive follicles of all follicles presented in the sections screened.

Fisher’s exact test between WT and FshrD580H females; P < 0.001.

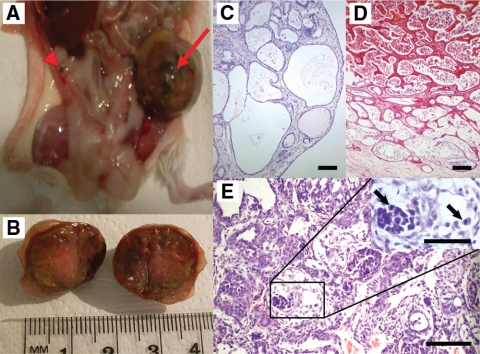

A subgroup of mFshrD580H mice develops ovarian teratomas

In addition to the other structural abnormalities, unilateral teratomas were found in about 20% of the ovaries (11/58) of the mFshrD580H females between 6 and 8 months of age (Fig. 4, A and B). In most of the cases, tumors were mature benign cysts with several differentiated tissue types such as bone, cartilage, fat, neuronal, respiratory, intestinal, and keratin-like elements (Fig. 4, C and D) (data not shown). In three cases, however, a focus of immature tissue was detected with blastic mesenchyme or syncytiotrophoblast-like cells, suggestive of teratocarcinoma (Fig. 4E) or chorioncarcinoma. Histologically identified mature teratoma was also found in one mFshrD580Y female older than 6 months (n = 55), as well as in one mFshr-wt female (n = 19) and in one of their WT littermate (n = 69), which is not surprising, because old FVB/N mice are known to be susceptible for teratomas (28).

Figure 4.

Macroscopic (A and B) and microscopic (C–E) presentation of ovarian teratomas in mFshrD580H females. The right ovary is hemorrhagic (A, arrowhead), characteristic of mFshrD580H females, whereas the left one (A, arrow, and B) presents an advanced teratoma. Squamous and cuboidal lined cysts (C) and osteogenesis (D) are typically seen in the teratomas. Area of poorly differentiated and necrotic immature teratoma (E) contains mitotic cells (inset, arrows). Scale bars, Main frames C–E, 100 μm; inset, 100 μm.

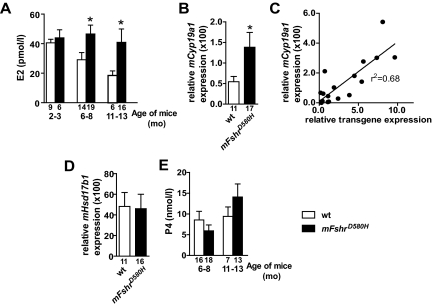

Expression of mFshrD580H increases ovarian estradiol (E2) but not progesterone biosynthesis

The results above suggested that the expression of mFshrD580H in granulosa cells accelerated the loss of small follicles, but the maturation of large follicles persisted (Figs. 2 and 3). In accordance, the mean E2 concentrations remained elevated in the tg females, in comparison with WT mice, up to the age of 1 yr in most of the females (Fig. 5A). Also the expression of the gene encoding cytochrome P450 aromatase (Cyp19a1) was increased (Fig. 5B) and this correlated with the level of transgene expression (Fig. 5C), whereas that of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (Hsd17b1) remained unchanged (Fig. 5D). Unlike E2 biosynthesis, tg expression did not affect ovarian progesterone (P4) production (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

E2 biosynthesis in mFshrD580H females and their WT littermates. A, Serum E2 concentrations in WT and tg females in the age groups 2–3, 6–8, and 11–13 months. B, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of Cyp19a1; and C, its correlation to the mFshrD580H expression in tg females. D, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of Hsd17b1 in WT and tg females. E, Serum P4 concentrations in aging WT and tg females. The samples for panel C have been collected from randomly cycling mice, and for the other panels from metestrus or diestrus. Relative gene expressions have been calculated as target gene mRNA copy number/mRlp7 mRNA copy number. Numbers of samples analyzed has been shown below each column. Bars, average + sem. In all panels: open bar, WT; filled bar, tg; *, P < 0.05.

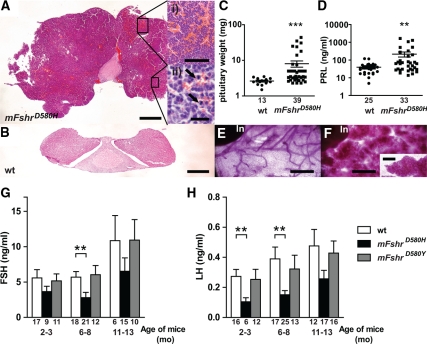

Effect of mFshrD580H expression on pituitary, mammary, and adrenal glands

Increased anterior pituitary size was obvious in the mFshrD580H females older than 6 months (Fig. 6, A–C). In the most pronounced cases, adenomatous growth was apparent with multiple blood-filled cavities (Fig. 6A, inset i) and abundant mitotic cells (Fig. 6A, inset ii). Elevated prolactin (PRL) levels (Fig. 6D and Supplemental Fig. 6, A–C) indicated that the pituitary tumors were prolactinomas. In addition, the virgin mFshrD580H females with high serum PRL and E2 demonstrated advanced lobulo-alveolar growth of the mammary gland (Fig. 6, E and F), typical for late pregnancy.

Figure 6.

Histology and function of the pituitary and mammary glands in mFshrD580H female mice. The pituitary of tg females is enlarged (A–C), contains blood-filled cavities (A, inset i) and mitotic cells (arrows in A, inset ii). PRL production is increased in tg females (D). Mammary gland of a 6-month-old WT mouse demonstrates basal branching (E), whereas the tissue of a tg virgin mouse shows intense lobulo-alveolar growth (F and inset). Serum FSH (G) and LH (H) concentrations are decreased in mFshrD580H but not in mFshrD580Y females during metestrus-diestrus. The samples with level under detection limit (0.1 ng/ml for FSH and 40 pg/ml for LH) have been calculated with that value. C, D, G, and H, Bars, average ± sem and numbers of samples analyzed are shown below graphs. G and H, Open bar, WT; filled bar; mFshrD580H mice; gray bar, mFshrD580Y mice. ln, lymphatic node. Scale bars, Main pictures A, B, E, and F, 500 μm; A, inset i, 100 μm; A, inset ii, 20 μm; F, inset, 100 μm. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

In contrast to PRL, mFshrD580H transgenesis led to decreased serum concentrations of FSH and LH (Fig. 6, G and H), to levels below the detection limit in most affected animals (Supplemental Fig. 6, D–F). In general, gonadotropin levels increased in both WT and tg animals upon aging, reflecting decreased negative feed-back due to depletion of ovarian follicles. The weaker mFSHRD580Y variant did not affect gonadotropin levels in comparison with WT littermates (Fig. 6, G and H), and also the phenotypic effects were milder than with the mFSHRD580H variant.

In the adrenal glands, age-related accumulation of foamy-looking multinucleated giant cells occurred in the cortico-medullary junction of the mFshrD580H females replacing the x-zone (Supplemental Fig. 7). These cells were positive for PAS-staining, characteristic of lipofuscin, and only few PAS-positive cells were located in the adrenal glands of WT mice. No obvious abnormalities were seen in the adrenal glands of mFshrD580Y, mFshr-wt, or mFshrD580Y-ki mice up to the age of 12 months (data not shown).

The level of ovarian transgene expression affects severity of phenotype

Many of the phenotypic characteristics of the mFshrD580H females displayed quantitative and qualitative differences between individual mice, even when assessed in the same sublines. In general, the severity of phenotypic signs in the ovary, adrenal gland, pituitary gland, and mammary gland correlated with the levels of ovarian transgene expression (Supplemental Figs. 5 and 8A). Thus the detected transgene expression levels likely reflect the life-time expression differences and not only temporary variations in the numbers of transgene-expressing follicles and granulosa cells. Occasionally, transgene expression was also detected in the nongonadal tissues of mFshrD580H females. However, in these cases, the transgene expression did not correlate with the phenotypes described (Supplemental Fig. 8, B–F), suggesting that abnormalities observed were ovary-dependent and not due to spurious tg expression in extragonadal tissues.

Discussion

The first disease-causing GPCR CAM was reported in rhodopsin in 1991 (29), and since then, numerous others have been described (30), including several in the glycoprotein hormone receptors hTSHR (18) and hLHCGR (9). One hot spot for CAMs in glycoprotein hormone receptors is the Asp(6,44) residue in the 6th transmembrane domain, that has been mutated to several other residues in affected patients (9,18). Introduction of the same mutations into mFSHR, Asp580His in particular, significantly increased the basal activity of the receptor, but did not generate promiscuous responsiveness to other ligands. Asp(6,44) in FSHR belongs to a conserved motif in glycoprotein receptors that in hTSHR has been shown to interact with residue Asn(7,49) to stabilize an inactive receptor conformation. Ligand binding or a mutation interfering with this interaction results in a conformation change of the transmembrane domains, including orientation of Asn(7,49) toward Asp(2.50), bringing about stabilization of the receptor in an active state (31). In addition, the hFSHR CAM, Leu(3,43), has been suggested to form a charge-reinforced hydrogen bond with Asp(6,44) (32), pointing to the importance of the 6th transmembrane motif in receptor inactivation/activation. Our results confirmed that Asp(6,44) is essential in maintenance of the inactive conformation also in mFSHR, and that its replacement, in particular with amino acid residues containing bulky aromatic (Tyr) or polar (His) side chains, may affect the formation of hydrogen bonds between the 6th and 7th transmembrane domains in the mFSHR similar to hTSHR CAMs (31), leading to significant constitutive activation of the receptor.

None of the modifications at Asp580 in the mFSHR relaxed the ligand-specific activation of the receptor toward LH or hCG. This is in contrast to activating mutations of the hFSHR previously described, where the constitutive activity is thought to decrease the activation barrier to the low affinity binding of other glycoprotein hormones (11,12,13,14,15,31,33). Modeling of rodent and human FSHR suggests differences in the hydrophobic environment of the 6th transmembrane domain (27,32), and thus, they are not directly comparable. Our results suggest that either Asp(6,44) itself is resistant to changes introducing promiscuous activation or, more likely, that this characteristic is specific for the mouse receptor, because substitution of the adjacent residue Thr(6,43) in hFSHR significantly changes ligand-specific activation (32). WT mFSHR was to some extent activated by high concentrations of hCG or LH similar to hFSHR, which in the latter case can cause spontaneous OHSS, when hCG concentration is exceptionally high (14).

We generated three different mouse models for CAM mFSHR, i.e. the mFSHRD580H or D580Y tg’s under the hAMH promoter, and the mFshrD580Y-ki line. For the first two lines, we also created a control line mFshr-wt to investigate possible phenotypic effects of WT mFSHR overexpression, but no detectable differences were observed between the tg mice and their WT littermates, as it has also been reported for the tg line overexpressing WT human FSHR (33). In agreement with its strongest constitutive activity, the mFSHRD580H mutant induced the most prominent phenotypic effects from infertility to tumors in tg females. However, because some phenotypes such as hemorrhagic cysts were found in the heterozygous mFshr-D580Y-ki females, even a single copy of the weaker mutant CAM gene was sufficient to disturb ovarian function. This is in line with the findings that relatively small increases in circulating FSH, PRL, and E2 levels can initiate OHSS in patients with pituitary adenoma (6). Hence, the intensity and timing of FSH signaling needs to be strictly regulated to secure proper ovarian function. This may be one reason why hFSHR is more resistant to mutation-induced constitutive activation than the other glycoprotein hormone receptors (27,32,34).

Interestingly, a subgroup of mFshrD580H females delivered larger litters than WT mice, whereas the rest were infertile/subfertile. There was a relatively large variation of the phenotype between individual mice, but it appeared to correlate with the level of ovarian mFshrD580H transgene expression. This may be explained by the observations that the use of the hAMH promoter can lead to mosaic female mice, whereby hAMH promoter-driven genes are unevenly expressed in granulosa cells (35). Expression of ovarian mFshrD580H enhanced the proliferation of granulosa cells and the proportion of the primary follicle to grow, thus leading to greater recruitment of follicles. FSHR interacts with other signaling pathways such as Activin/Smad3 (36) and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/acute transforming retrovirus thymoma protein kinase (P13K/Akt) (37,38,39) and thus participate in regulation of proliferation and apoptosis of granulosa cells and subsequently the follicle growth. Similar to mFshrD580H mice, mice with granulosa cell-specific knockout of Pten, a suppressor of the FSH-activated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/acute transforming retrovirus thymoma protein kinase (P13K/Akt) pathway (37), and mice overexpressing FSH under control of the rat insulin II promoter (40) initially produce large litters. More abundant expression of the CAM transgene, mFshrD580H, on the other hand, accelerated further follicular loss, and enhanced excessive ovarian E2 production evoked the detected abnormalities in peripheral tissues. Increased serum FSH in perimenopausal women has been suggested to promote the final depletion of the follicle reserve (41) and to rescue the ovarian follicles that would otherwise have been excluded from selection (42). Consequently, follicles with poor quality, possibly reflected by their hemorrhagic and cystic appearance in the mFshr CAM mice, are also recruited.

Several of the mFshrD580H females presented with pseudopregnancy-type acyclicity and remained infertile during the 5 months of fertility testing. The various abnormalities observed in the mFshrD580H expressing females were likely to compromise fertility. First, the hormonal status of the mice, including elevated E2 and PRL levels, was likely to affect the vaginal epithelium and its capacity to support implantation. Hyperprolactinemia could also decrease pulsatile LH-surges, and the occasionally found luteinized unruptured follicles provided evidence for disturbed ovulations. Some mFshrD580H mice developed teratomas associated with almost complete lack of follicles in the affected ovary. Finally, the number of primordial and primary follicles declined faster in mFshrD580H than WT mice, leading eventually to premature loss of follicles. Accelerated loss of small follicles, though not as evident as in mFshr CAM mice, also occurs in Tg-mFSH mice (40), indicating that the phenomenon is not due to the hAMH promoter-driven expression of mFSHR, but a genuine consequence of enhanced signaling through the mutant mFSHR.

Hemorrhagic cysts were common in all mFSHR CAM mice, especially upon aging. The cysts are frequent also in some other mice models such as the estrogen receptor α knockout (43), aromatase knockout (44), FSH overexpressing (45), and hCG overexpressing mice (46). Enhanced gonadotropin action is the common feature of these models, suggesting this to be the cause of the phenotype rather than the lack of auto/paracrine estrogen action in the ovary. Red blood cells leak from the theca cell layer to granulosa cells filling the antrum, implying increased vascular permeability in the thecal layer, and/or premature onset of follicular angiogenesis. Gonadotropins have been proposed to have tissue-specific angiogenic effects and in pathological conditions such as OHSS, the strictly regulated interaction between gonadotropins and angiogenic factors is disturbed (47). In granulosa cells, FSH regulates the expression of several angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, also known as vascular permeability factor (48), and thus the expression of FSHR CAM may disturb the control of ovarian angiogenesis.

Expression of the mFshrD580H CAM resulted in a modest increase in granulosa cell estrogen biosynthesis, thus resembling more a recent tg FSH mouse model (40) than another mouse model expressing supraphysiological concentration of FSH and showing over 50-fold increase in E2 production (45). mFshrD580H increased the expression of mCyp19a1, the rate-limiting factor in E2 biosynthesis (49), but not the expression of mHsd17b1, already abundantly expressed. Increased feedback of ovarian hormones (E2, inhibin) evidently led to decreased FSH and LH levels in the most affected cases as well as to increased growth of the pituitary gland and enhanced PRL secretion. Besides stimulating lactotroph cell growth and PRL secretion, E2 also augments target cell sensitivity to PRL by up-regulating PRLR expression and via PRL-induced signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (Stat5) activation (50,51,52). In mFshrD580H females, the elevated E2 and PRL levels can thus cooperate at several levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, impinging on the LH pulses (50,53), ovulation and maintenance of corpora lutea, and on development and function of the mammary gland. The mFshrD580H females with the highest ovarian transgene expression displayed intense lobulo-alveolar growth of the mammary glands, akin to late pregnancy. This phenotype mimics closely that of hCGβ+ mice (46) with characteristically high PRL production and peripubertally increased E2 secretion. The mFshrD580H CAM females, however, did not develop by 12 months palpable mammary gland tumors similarly to those observed in hCGβ+ mice, suggesting a difference in quantity or quality of the growth stimuli and response.

Another nongonadal effect of the mFSHRD580H CAM was seen in the adrenal glands, with dramatic accumulation of foamy multinucleated cells in the cortico-medullary junction along with disappearance of the x-zone. WT female mice lose the x-zone during pregnancy, so the absence of this zone in virgin mFshrD580H females confirms their pseudopregnancy-like phenotype. Due to its histological appearance and positive PAS staining, the pigmented material is probably lipofuscin, also called lipogenic/aging pigmentation, or ceroid if pathological in origin (54). Accumulation of lipofuscin in the adrenal gland is a known phenomenon of aged mice (55), and previous studies have shown that also chronic estrogen treatment induces it (55,56). A similar layer of giant cells is also observed in adrenal glands of female bLHβ-CTP (57), ubiquitin C-hCGβ mice (46), and of male tg mice overexpressing aromatase (58), all of them showing increased E2 production and in which gonadectomy and antiestrogen treatment reduce the premature formation of the lipofuscin layer. Accumulation of lipofuscin also occurs in the human adrenal gland, with the extreme state of rare “black adenomas” (59), suggesting clinical relevance for the phenomenon.

Interestingly, PAS-positive cells of unknown origin were also observed in ovaries of the mFshrD580H mice. This points to premature aging of the ovaries in addition to their early loss of follicles and/or delayed structural luteolysis of corpora lutea leading to formation of corpus albicans-like structures (60). Intensive PAS-stained hyperplasia was often accompanied with thickening of the surface epithelium. E2 has been shown to have opposite effects on the ovarian surface epithelium being able to act in both tumor suppressing and promoting manner (61); E2 can induce oxidative stress DNA damage (62) and prevent apoptosis in ovarian surface epithelial cells (63). Thus, the thickening of the epithelium may also be due to the increased circulating E2 in the tg females.

About 20% of the ageing mFshrD580H females developed ovarian teratomas with typical ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal structures. Most of them were mature, i.e. containing benign well-differentiated cells, but also immature areas of growth were seen in a few cases. Teratomas originate from nonovulated germ cells initiating parthenogenetic development, but their etiology has otherwise remained largely unknown. Few predisposing factors identified (64,65,66) together with segregation analysis of teratoma formation in various mouse lines suggest that teratoma development is a multigenic trait involving a few permissive alleles (67). In addition to mFshrD580H females shown here, tg hCGαβ+ mice producing high excess of bioactive hCG in circulation develop ovarian teratomas (68). Together, these mouse models, and the negative data on Fshr or FshrD580H expression in the tumors (Supplemental Fig. 9), imply that high gonadotrophin stimulation of granulosa cells interferes with oocyte maturation and induces teratomatous growth of oocytes. On the other hand, patients with OHSS or premature ovarian failure have not been reported to be susceptible to teratomas, which may due to their multigenic background. Species-specific factors may also play role, or rarity of strong mutations such as D6.44H. Interestingly, the D6.44H mutant form of hCGLHR has been detected only in as a somatic mutation in Leydig cell tumors, but not in patients with testotoxicosis suggesting specific characteristics of the mutation (9).

Few tg mouse lines expressing GPCR CAMs have been successfully generated. One such line is the parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related type 1 receptor-H223R mouse line that showed several skeletal abnormalities (69). In some cases instead, in vitro characterized CAM receptors have not been found to be constitutively active in tg mice due to counter-acting mechanisms such as binding to arrestin (70). Several pathological states in the mFshr CAM mice presented here evidently demonstrate that the possible desensitization mechanisms cannot compensate for the constitutive activation at position Asp580. The tg line expressing mFSHRD567G with weak constitutive activity shows a detectable phenotype only in the gonadotropin-deficient hypogonadal background, with increased testis size and postmeiotic germ cells that are absent in controls (33,71). Conspicuously, no obvious female phenotype, in either the normal or hypogonadal background (33,71), was found in these mice, demonstrating differences between mFSHR activating mutations, possibly related to the degree of constitutive activity.

In summary, gain-of-function mutations in the mFshr have serious phenotypic consequences for female mice. Natural and laboratory-designed mutants have shown that constitutive activation of the cognate human receptor is also possible. Although mFshrD580H is a laboratory-designed form and CAMs in general can differ in their characteristics, it may reflect the array of abnormalities FSHR CAMs can induce. A similar array of phenotypes can also be expected in humans expressing FSHR CAMs. Hence, strong gain-of-function mutations in the hFSHR may lead, in addition to OHSS, to conditions such as premature ovarian failure, formation of hemorrhagic cysts, and abnormal hormone balance of the pituitary-gonadal axis. Furthermore, as found in the mFshr CAM female mice, the human phenotypes may include ovarian germ cell tumors. This would also prompt closer follow-up of the FSHR CAM patients with OHSS (11,12,13,14).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Gordon (University of Colorado Health Science Center, Denver, CO) for p-loxp-2FRT-PGKneo targeting vector, Professor Axel Themmen (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for pADneo2 C6-BGL reporter gene plasmid, Dr. J.-Y. Picard (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale) for SMAT1 cells, and Professors Kate Hardy and Jaroslav Stark (Imperial College London) for their valuable advice. We also thank Jonathan Godwin, Zoe Webster, and Jane Selby at Embryonic Stem Cell Facility, Medical Research Council Clinical Sciences Centre, Imperial College London, and Nina Messner and Heli Niittymäki at the Department of Physiology, University of Turku, for pronuclear and blastocyst injections and embryo rederivation, and Jonna Palmu, Taina Kirjonen, and Nicholas Wood for their skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, Wellcome Trust Grant 063552, 082101/Z/07/Z (to I.H.), and National Institutes of Health Grant HD22196 (to D.L.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 19, 2010

Abbreviations: AMH, Anti-Müllerian hormone; CAM, constitutively active mutant; CG, choriogonadotropin; E2, estradiol; FSHR, FSH receptor; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; hLH, human LH; hLHCGR, hLH/CG receptor; hTSHR, human thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor; ki, knock in; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; PRL, prolactin; rh, recombinant human; RT, real time; tg, transgenic.

References

- Aittomäki K, Lucena JL, Pakarinen P, Sistonen P, Tapanainen J, Gromoll J, Kaskikari R, Sankila EM, Lehväslaiho H, Engel AR, Nieschlag E, Huhtaniemi I, de la Chapelle A 1995 Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell 82:959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Themmen APN, Huhtaniemi IT 2000 Mutations of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors: elucidating the physiology and pathophysiology of pituitary-gonadal function. Endocr Rev 21:551–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews CH, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, Adams M, Tone Y, Gambino G, Casagrande S, Tedeschini G, Benedetti A, Chatterjee VK 1993 Primary amenorrhoea and infertility due to a mutation in the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. Nat Genet 5:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktay K, Briggs D, Gosden RG 1997 Ontogeny of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene expression in isolated human ovarian follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:3748–3751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannikki AS, Zhang FP, Huhtaniemi IT 1995 Ontogeny of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene expression in the rat testis and ovary. Mol Cell Endocrinol 107:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper O, Geller JL, Melmed S 2008 Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome caused by an FSH-secreting pituitary adenoma. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4:234–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Spandorfer S, Fasouliotis SJ, Lin K, Rosenwaks Z 2005 Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation caused by a follicle-stimulating hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma. Fertil Steril 83:208–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Higashitsuji H, Yoshinaga K, Terada Y, Ito K, Ikeda H 2004 Management of ovarian hyperstimulation due to follicle-stimulating hormone-secreting gonadotroph adenoma. BJOG 111:1297–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenker A 2002 Activating mutations of the lutropin choriogonadotropin receptor in precocious puberty. Recept Channel 8:3–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromoll J, Simoni M, Nieschlag E 1996 An activating mutation of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor autonomously sustains spermatogenesis in a hypophysectomized man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:1367–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasseur C, Rodien P, Beau I, Desroches A, Gérard C, de Poncheville L, Chaplot S, Savagner F, Croué A, Mathieu E, Lahlou N, Descamps P, Misrahi M 2003 A chorionic gonadotropin-sensitive mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor as a cause of familial gestational spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. N Engl J Med 349:753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanelli L, Delbaere A, Di Carlo C, Nappi C, Smits G, Vassart G, Costagliola S 2004 A mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor as a cause of familial spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:1255–1258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits G, Campillo M, Govaerts C, Janssens V, Richter C, Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S 2003 Glycoprotein hormone receptors: determinants in leucine-rich repeats responsible for ligand specificity. EMBO J 22:2692–2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leener A, Montanelli L, Van Durme J, Chae H, Smits G, Vassart G, Costagliola S 2006 Presence and absence of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor mutations provide some insights into spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome physiopathology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caltabiano G, Campillo M, De Leener A, Smits G, Vassart G, Costagliola S, Pardo L 2008 The specificity of binding of glycoprotein hormones to their receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:2484–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leener A, Caltabiano G, Erkan S, Idil M, Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S 2008 Identification of the first germline mutation in the extracellular domain of the follitropin receptor responsible for spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Mutat 29:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H 1995 Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relationships in G-protein coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci 25:366–428 [Google Scholar]

- Duprez L, Parma J, Van Sande J, Rodien P, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Abramowicz M 1998 TSH receptor mutations and thyroid disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 9:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M, Manna PR, Huhtaniemi I 1999 Molecular cloning of the mouse follicle-stimulating hormone receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid: functional expression of alternatively spliced variants and receptor inactivation by a C566T transition in exon 7 of the coding sequence. Biol Reprod 60:1515–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutertre M, Rey R, Porteu A, Josso N, Picard JY 1997 A mouse Sertoli cell line expressing anti-Mullerian hormone and its type II receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 136:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmler A, Stratowa C, Czernilofsky AP 1993 Functional testing of human dopamine D1 and D5 receptors expressed in stable cAMP-responsive luciferase reporter cell lines. J Recept Res 13:79–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannikko A, Pakarinen P, Manna PR, Beau I, Misrahi M, Aittomäki K, Huhtaniemi I 2002 Functional characterization of the human FSH receptor with an inactivating Ala189Val mutation. Mol Hum Reprod 8:311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E 1922 The oestrus cycle in the mouse. Am J Anat 30:297–371 [Google Scholar]

- Myers M, Britt KL, Wreford NG, Ebling FJ, Kerr JB 2004 Methods for quantifying follicular numbers within the mouse ovary. Reproduction 127:569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs SA, Stark J, Dilworth SM, Franks S, Hardy K 2007 Abnormal preantral folliculogenesis in polycystic ovaries is associated with increased granulosa cell division. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:4418– 4426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva-Buttkus P, Jayasooriya GS, Mora JM, Mobberley M, Ryder TA, Baithun M, Stark J, Franks S, Hardy K 2008 Effect of cell shape and packing density on granulosa cell proliferation and formation of multiple layers during early follicle development in the ovary. J Cell Sci 121:3890–3900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao YX, Mizrachi D, Segaloff DL 2002 Chimeras of the rat and human FSH receptors (FSHRs) identify residues that permit or suppress transmembrane 6 mutation-induced constitutive activation of the FSHR via rearrangements of hydrophobic interactions between helices 6 and 7. Mol Endocrinol 16:1881–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler JF, Stokes W, Mann PC, Takaoka M, Maronpot RR 1996 Spontaneous lesions in aging FVB/N mice. Toxicol Pathol 24:710–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen TJ, Inglehearn CF, Lester DH, Bashir R, Jay M, Bird AC, Jay B, Bhattacharya SS 1991 Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa: four new mutations in rhodopsin, one of them in the retinal attachment site. Genomics 11:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao YX 2008 Constitutive activation of G protein-coupled receptors and diseases: insights into mechanisms of activation and therapeutics. Pharmacol Therapeut 120:129–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S 2004 A molecular dissection of the glycoprotein hormone receptors. Trends Biochem Sci 29:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Tao YX, Ryan GL, Feng X, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL 2007 Intrinsic differences in the response of the human lutropin receptor versus the human follitropin receptor to activating mutations. J Biol Chem 282:25527–25539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan CM, Lim P, Robson M, Spaliviero J, Handelsman DJ 2009 Transgenic mutant D567G but not wild-type human FSH receptor overexpression provides FSH-independent and promiscuous glycoprotein hormone Sertoli cell signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E1022–E1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo M, Osuga Y, Kobilka BK, Hsueh AJ 1996 Transmembrane regions V and VI of the human luteinizing hormone receptor are required for constitutive activation by a mutation in the third intracellular loop. J Biol Chem 271:22470–22478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lécureuil C, Fontaine I, Crepieux P, Guillou F 2002 Sertoli and granulosa cell-specific Cre recombinase activity in transgenic mice. Genesis 33:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomic D, Miller KP, Kenny HA, Woodruff TK, Hoyer P, Flaws JA 2004 Ovarian follicle development requires Smad3. Mol Endocrinol 18:2224–2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan HY, Liu Z, Cahill N, Richards JS 2008 Targeted disruption of Pten in ovarian granulosa cells enhances ovulation and extends the life span of luteal cells. Mol Endocrinol 22:2128–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzicker-Dunn M, Maizels ET 2006 FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell Signal 18:1351–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayampilly PP, Menon KM 2009 Follicle stimulating hormone inhibits AMPK activation and promotes cell proliferation of primary granulosa cells in culture through an Akt dependent pathway. Endocrinology 150:929–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTavish KJ, Jimenez M, Walters KA, Spaliviero J, Groome NP, Themmen AP, Visser JA, Handelsman DJ, Allan CM 2007 Rising follicle-stimulating hormone levels with age accelerate female reproductive failure. Endocrinology 148:4432–4439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SJ, Nelson JF 1990 Follicular depletion during the menopausal transition. Ann NY Acad Sci 592:13–20; discussion 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Velde ER, Pearson PL 2002 The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update 8:141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomberg DW, Couse JF, Mukherjee A, Lubahn DB, Sar M, Mayo KE, Korach KS 1999 Targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor-α gene in female mice: characterization of ovarian responses and phenotype in the adult. Endocrinology 140:2733–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt KL, Drummond AE, Cox VA, Dyson M, Wreford NG, Jones ME, Simpson ER, Findlay JK 2000 An age-related ovarian phenotype in mice with targeted disruption of the Cyp 19 (aromatase) gene. Endocrinology 141:2614–2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Palapattu G, Wang P, Woodruff TK, Boime I, Byrne MC, Matzuk MM 1999 Transgenic models to study gonadotropin function: the role of follicle-stimulating hormone in gonadal growth and tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol 13:851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulli SB, Kuorelahti A, Karaer O, Pelliniemi LJ, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I 2002 Reproductive disturbances, pituitary lactotrope adenomas, and mammary gland tumors in transgenic female mice producing high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 143:4084–4095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger K, Baal N, McKinnon T, Münstedt K, Zygmunt M 2007 The gonadotropins: tissue-specific angiogenic factors? Mol Cell Endocrinol 269:65–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam H, Weck J, Maizels E, Park Y, Lee EJ, Ashcroft M, Hunzicker-Dunn M 2009 Role of the PI3-kinase and ERK pathways in the induction of HIF-1 activity and the HIF-1 target VEGF in ovarian granulosa cells in response to follicle stimulating hormone. Endocrinology 150:915–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick SL, Richards JS 1991 Regulation of cytochrome P450 aromatase messenger ribonucleic acid and activity by steroids and gonadotropins in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology 129:1452–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM, Kieser DC, Steyn FJ, Grattan DR 2008 Hypothalamic prolactin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid levels, prolactin signaling, and hyperprolactinemic inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion are dependent on estradiol. Endocrinology 149:1562–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd RV 1983 Estrogen-induced hyperplasia and neoplasia in the rat anterior pituitary gland. An immunohistochemical study. Am J Pathol 113:198–206 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asa SL, Ezzat S 1998 The cytogenesis and pathogenesis of pituitary adenomas. Endocr Rev 19:798–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Becker IR, Selmanoff M, Wise PM 1986 Hyperprolactinemia alters the frequency and amplitude of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the ovariectomized rat. Neuroendocrinology 42:328–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehafer SS, Pearce DA 2006 You say lipofuscin, we say ceroid: defining autofluorescent storage material. Neurobiol Aging 27:576–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C ed. 1996 Lipogenic pigmentation, adrenal cortex, mouse. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- Alpert M 1953 Hormonal induction of deposition of ceroid pigment in the mouse. Anat Rec 116:469–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kero J, Poutanen M, Zhang FP, Rahman N, McNicol AM, Nilson JH, Keri RA, Huhtaniemi IT 2000 Elevated luteinizing hormone induces expression of its receptor and promotes steroidogenesis in the adrenal cortex. J Clin Invest 105:633–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Nokkala E, Yan W, Streng T, Saarinen N, Wärri A, Huhtaniemi I, Santti R, Mäkelä S, Poutanen M 2001 Altered structure and function of reproductive organs in transgenic male mice overexpressing human aromatase. Endocrinology 142:2435–2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y, Tanaka H, Murakami H, Ninomiya T, Yamashita Y, Ichikawa M, Kondoh T, Chiba T 1997 A functioning black adenoma of the adrenal gland. Intern Med 36:398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales C, García-Pardo L, Reymundo C, Bellido C, Sánchez-Criado JE, Gaytán F 2000 Different patterns of structural luteolysis in the human corpus luteum of menstruation. Hum Reprod 15:2119–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed V, Zhang X, Lau KM, Cheng R, Mukherjee K, Ho SM 2005 Profiling estrogen-regulated gene expression changes in normal and malignant human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Oncogene 24:8128–8143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds DA, Merchenthaler I, Flaws JA 2008 Methoxychlor and estradiol induce oxidative stress DNA damage in the mouse ovarian surface epithelium. Toxicol Sci 105:182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KC, Kang SK, Tai CJ, Auersperg N, Leung PC 2001 Estradiol up-regulates antiapoptotic Bcl-2 messenger ribonucleic acid and protein in tumorigenic ovarian surface epithelium cells. Endocrinology 142:2351–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fafalios MK, Olander EA, Melhem MF, Chaillet JR 1996 Ovarian teratomas associated with the insertion of an imprinted transgene. Mamm Genome 7:188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N, Watanabe N, Furuta Y, Tamemoto H, Sagata N, Yokoyama M, Okazaki K, Nagayoshi M, Takeda N, Ikawa Y, Aizawa S 1994 Parthenogenetic activation of oocytes in c-mos-deficient mice. Nature 370:68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GH, Bugni JM, Obata M, Nishimori H, Ogawa K, Drinkwater NR 1997 Genetic dissection of susceptibility to murine ovarian teratomas that originate from parthenogenetic oocytes. Cancer Res 57:590–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppig JJ, Wigglesworth K, Varnum DS, Nadeau JH 1996 Genetic regulation of traits essential for spontaneous ovarian teratocarcinogenesis in strain LT/Sv mice: aberrant meiotic cell cycle, oocyte activation, and parthenogenetic development. Cancer Res 56:5047–5054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtaniemi I, Rulli S, Ahtiainen P, Poutanen M 2005 Multiple sites of tumorigenesis in transgenic mice overproducing hCG. Mol Cell Endocrinol 234:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipani E, Lanske B, Hunzelman J, Luz A, Kovacs CS, Lee K, Pirro A, Kronenberg HM, Jüppner H 1997 Targeted expression of constitutively active receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide delays endochondral bone formation and rescues mice that lack parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:13689–13694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Franson WK, Gordon JW, Berson EL, Dryja TP 1995 Constitutive activation of phototransduction by K296E opsin is not a cause of photoreceptor degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:3551–3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood M, Tymchenko N, Spaliviero J, Koch A, Jimenez M, Gromoll J, Simoni M, Nordhoff V, Handelsman DJ, Allan CM 2002 An activated human follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor stimulates FSH-like activity in gonadotropin-deficient transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol 16:2582–2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.