Abstract

Until recently, anion (Cl−) channels have received considerably less attention than cation channels. One reason for this may be that many Cl− channels perform functions that might be considered cell biological, like fluid secretion and cell volume regulation, whereas cation channels have historically been associated with cellular excitability that typically happens more rapidly. In this review, we discuss the recent explosion of interest in Cl− channels with special emphasis on new and often surprising developments over the last 5 years. This is exemplified by the findings that more than half of the ClC family members are antiporters, and not channels as was previously thought, and that bestrophins, previously prime candidates for Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, have been supplanted by the newly discovered anoctamins and now hold a tenuous position in the Cl− channel world.

Keywords: channelopathies, ion transport, bestrophin, TMEM16, anoctamin, ClC

A Short History of Chloride in Biological Systems

Not long ago, Cl− channels were the Rodney Dangerfield of the ion channel field. Rodney Dangerfield (1921–2004) was a comedian who became famous for his joke: "I get no respect. I played hide-and-seek, and they wouldn't even look for me.” After a small flurry of work on Cl− channels in the 50’s and 60’s, interest in Cl− channels dwindled until the 1990’s. In the first edition of the “bible” on ion channels published in 1984 (1), less than 3 pages were devoted to Cl− channels, because it was thought that Cl− was usually in electrochemical equilibrium across cell membranes. This made Cl− less interesting than other ions that exhibited the potential to do some work. This mis-impression occurred because many early studies on Cl− were performed on skeletal muscle and erythrocytes where resting Cl− permeability is very high so that even if there is active Cl− transport present, Cl− is in electrochemical equilibrium. The demonstration that Cl− is actively transported in squid axons (2) and secreted (as HCl) by stomach (3) did not seem to attract much attention. Even the discovery that the inhibitory action of GABA was caused by an increased Cl− conductance did little to dispel the idea that Cl− could be out of electrochemical equilibrium. Because the reversal potentials of GABA-induced i.p.s.p.’s were very close to the resting potential, it was reasonably concluded that “normally Cl− ions are in electro-chemical equilibrium across the membrane” (4).

Into the 1990’s, the position of Cl− channels in cellular physiology remained in limbo. In Hille’s 1992 second edition, the 4-page section devoted to Cl− channels entitled “Chloride channels stabilize the membrane potential” concluded that Cl− channels have “uncertain physiological significance in many cell types” (5), but by 2001, the Cl− channel section was renamed “Cl− Channels Have Multiple Functions” (6). In the 10-year interim between 1992 and 2001, Cl− channels had begun to acquire some respectability, largely because two Cl− channels linked to human disease, CFTR and ClC-1, were cloned.

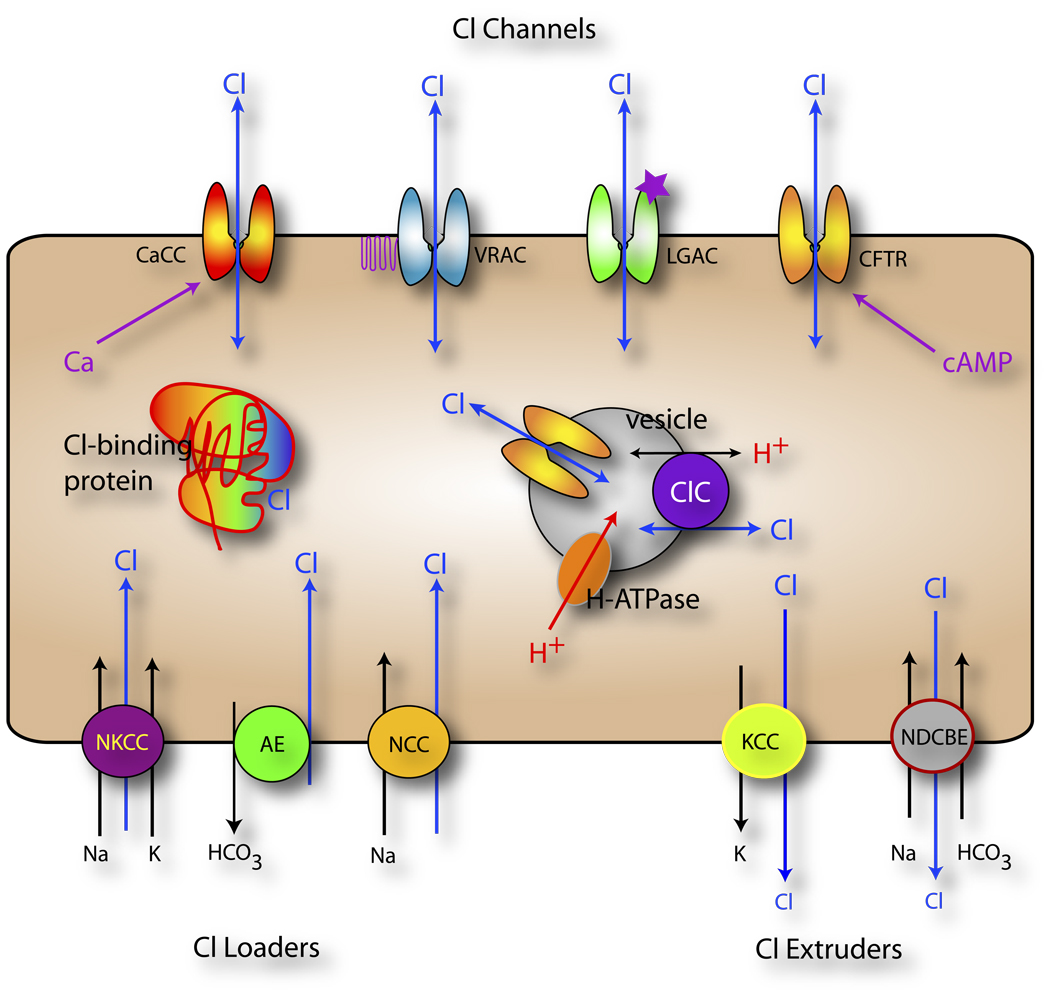

It is now clear that in most cells, Cl− is actively transported and is out of electrochemical equilibrium and is therefore capable of doing work and signaling (Fig. 1). For example, epithelial cells, immature neurons, sensory neurons express transporters like the Na-independent Cl−-HCO3− exchangers (AE1-3, SLC4A1-3), the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1-2, SLC12A1-2), or the Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC, SLC12A3) that pump Cl− into the cell. In epithelial cells, the resulting high intracellular Cl− concentration drives fluid secretion when Cl− passively exits the cell through apical Cl− channels and is followed by Na+ and water. Other cell types, such as most mature neurons, mainly express transporters that pump Cl− out of the cell such as the K+-Cl− cotransporters (KCC1-4, SLC12A4-7) and Na+-dependent Cl−-HCO3− exchangers (NDCBE, SLC4A8-10). In mature neurons, the low intracellular Cl− concentration is the basis for the typical hyperpolarizing action of GABA. In contrast, immature neurons express Cl− loaders so that GABA produces depolarizing postsynaptic potentials that may be important in stabilizing developing synapses (7).

Figure 1. Cellular Chloride Signaling.

Cells actively transport Cl− across the plasma membrane by transporters that accumulate Cl− intracellularly (Cl− loaders including the Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporters NKCC, Cl−-HCO3− exchangers AE, and Na+-Cl− cotransporters NCC) or pump Cl− out of the cell (K+-Cl− cotransporters KCC and Na+-dependent Cl− - HCO3− exchanger NDCBE). Cl− flows passively across a variety of Cl− channels in the plasma membrane including Ca-activated Cl− channels (CaCC), cAMP-activated Cl− channels (CFTR), cell-volume regulated anion channels (VRAC), and ligand-gated anion channels (GABAA and glycine receptors). In addition, Cl− channels and transporters are found in intracellular membranes, such as the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, and play a role in regulating intra-vesicular pH and Cl− concentration. Intravesicular pH and [Cl−] are important in vesicular trafficking (183). Finally, many proteins are regulated by Cl− as depicted by the Cl− binding protein.

The expression of Cl− transporters is regulated both temporally and spatially, so that resting intracellular [Cl−] is dynamically modulated. Dramatic changes in intracellular [Cl−] have been documented to occur both slowly during development and more acutely in response to synaptic activity (8–10). If intracellular [Cl−] is dynamic, this raises the possibility that Cl− might function as a second messenger. There are numerous examples of proteins whose activity is dependent upon or regulated by Cl− (Table 1). For example, the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 is activated by low intracellular Cl−via a Cl−-sensitive protein kinase which is likely to be a WNK kinase (11, 12).

TABLE 1.

Cl-binding and Cl-regulated proteins

| Protein/system | reference |

|---|---|

| AML1 transcription factors | (164) |

| angiotensin-converting enzyme I | (165) |

| atrionaturietic peptide receptor | (166) |

| Blood clotting cascade | (167) |

| cathepsin-C | (168) |

| Cryo-IgG | (167) |

| glucose-6-phosphatase | (169) |

| glycogen synthase phosphatase | (170) |

| G-proteins | (171) |

| H-ATPase (chromaffin granule) | (172) |

| hemoglobin | (173) |

| Cl-dependent protein kinases | (174) |

| Na-H exchanger | (175) |

| Slo-2 K channel | (176) |

| Photosystem II | (177) |

| RNase-A | (178) |

| Superoxide dismutase | (179) |

| Transferrin | (180) |

| Yhak enterobacterial bicupin | (181) |

| WNK kinases | (11) |

| α-amylase | (182) |

Cl− channels exhibit very low selectivity among inorganic anions (Br−, I−, Cl−) and some channels even allow some large organic anions to permeate (e.g.;(13)). For this reason they should more precisely be called “anion channels”. The term “Cl− channel” may be an appropriate default term because Cl− is usually the predominant anion in biological systems. But, despite its lower abundance, HCO3− is a physiologically important anion in biological systems. CFTR-dependent HCO3− secretion is important in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis, although questions remain how much HCO3− transport occurs via CFTR itself and HCO3 − transporters such as SLC26A3 that are regulated by CFTR (e.g.,(14, 15)). HCO3− is significantly permeant through bestrophin channels (e.g.; (16)), but the physiological relevance of this observation remains to be demonstrated. Superoxide is another low abundance, but highly significant, biological anion. Recently it has been suggested that ClC-3 may be a pathway by which superoxide exits endosomes (17, 18).

Chloride channel dysfunction produces human disease

Interest in Cl− channels in the 1990’s was flamed by the finding that several human diseases are Cl− channelopathies.

Myotonia congenita

In the 1960’s and 1970’s Shirley Bryant established that myotonia congentia was related to a defect in the skeletal muscle Cl− conductance (19, 20) by showing that myotonic muscle fibers had an increased membrane resistance and decreased Cl− conductance. Normal muscle fibers in low Cl− medium behaved like myotonic fibers; they were hyperexcitable and tended to fire action potentials spontaneously. Thomas Jentsch’s expression cloning in 1990 of the ClC channels (21) then paved the way for showing that myotonia congenita is caused by mutations in the ClC-1 channel (22, 23). Some of the myotonia-causing ClC-1 mutations alter voltage sensitivity (24), whereas others alter relative cation/anion permeability (25).

The mechanism of myotonia illustrates how Cl− channel function can be subtle. In muscle, the Na+-K+ ATPase sets up transmembrane K+ gradients, and inwardly rectifying K+ channels establish the resting membrane potential (Em ~ EK). Because active Cl− transport is relatively small and the resting Cl− conductance is high, Cl− distributes passively across the plasma membrane (ECl = Em ~ EK) (26, 27). Because the Cl− conductance is several times larger than the K+ conductance, the Cl− battery acts as a very strong buffer of membrane potential. When K+ accumulates extracellularly in the transverse tubules during muscle activity, EK changes transiently. One would expect this to depolarize the muscle, but the large Cl− conductance keeps the resting membrane potential near ECl, which is slow to change and remains near the resting EK. In myotonic muscle, the accumulated K+ quickly depolarizes the muscle fiber and repetitive activity and hyperexcitability develops (28).

Cystic fibrosis

Although the first indication that cystic fibrosis (CF) was an electrolyte disturbance was the discovery in 1953 that the sweat of CF patients was unusually salty (29), it was nearly 30 years before it was proposed that the disease was caused by a defect in Cl− transport (30) and 35 years before it was shown to be a Cl− channelopathy (31). The proposal that CF was caused by a problem of Cl− balance was based on the finding that CF sweat duct and airways exhibited very low Cl− permeabilities (30, 32). In 1989, the gene (CFTR) responsible for CF was positionally cloned (33–35), but it was not until CFTR was incorporated into artificial lipid bilayers that it was universally agreed that CFTR was a Cl− channel (36). But, even though it is clear that CFTR is a Cl− channel, its evolutionary roots show that it evolved from a transporter (37, 38).

Despite the identification of the molecule responsible for CF, our understanding how CFTR dysfunction causes CF remains incomplete. In the simplest view, CF lung disease reflects the failure of the innate immune system of the lung to defend against inhaled bacterial organisms. Mechanisms by which CFTR dysfunction produces lung disease include impaired airway submucosal gland function, abnormal immune cell response, altered airway surface liquid composition and volume, and defective organellar acidification (39). But, the mechanisms are complicated, because CFTR not only functions as a Cl− channel, but regulates other ion channels and transporters including the epithelial Na+ channel ENaC which plays a key role in Na+ reabsorption. Mice with CFTR knocked out do not develop lung disease, but knockout of ENaC produces a disease very similar to that of CF (40). Thus, it seems that both the Cl− channel and regulatory functions of CFTR are important in the pathophysiology of CF.

In recent years, the number of human diseases caused by disorders in Cl− channel and transporter function has grown to include over a dozen diseases (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Disorders of Chloride Transport

| Human disease | Protein/gene | defective function |

|---|---|---|

| Anderman syndrome | KCC3 / SLC12A6 | Neural development |

| Bartter syndrome Type I | NKCC /SLC12A1 | Renal salt balance |

| Bartter syndrome Type III | ClC-Kb /CLCNKB | Renal salt balance |

| Bartter syndrome Type IV with deafness |

Barttin /BSND | Renal salt loss, Endolymph secretion |

| Congenital Chloride Diarrhea | SLC26A3 | Intestinal fluid secretion |

| Deafness | KCC4 / SLC12A7 | Potassium recycling |

| Dent’s disease | ClC-5 / CLCN5 | Endosomal acidification |

| Distal renal tubule acidosis | AE1 / SLC4A1 | Renal pH balance |

| Epilepsy | GABAA receptor γ2 | Synaptic inhibition |

| Hyperekplexia | Gycine receptor / GLRA1 | Synaptic inhibition |

| Idiopathic generalized epilepsy* | CLC-2 / CLCN2 | Cl− channel deactivation |

| Juvenile myoclonus epilepsy | GABAA receptor α1 | Synaptic inhibition |

| Myotonia cogenita | ClC-1 / CLCN1 | Membrane potential |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis | CLC-7 / CLCN7 | Lysosomal dysfunction |

| Osteopetrosis | CLC-7 / CLCN7 | Acid secretion by osteoclasts |

| Ostm1 / OSTM1 | ||

| Spherocytosis | AE1 / SLC4A1 | Membrane stability |

| Vitelliform macular dystrophy | Bestrophin-1/ VMD2 | RPE Cl− transport ? |

Susceptibility gene.

Chloride channel families and principles of organization

Studies on cation channels over the past several decades have revealed certain similarities and guiding principles of operation (such as the 2-transmembrane domain-re-entrant loop structure of the pore, the positively charged voltage sensor, their heteromeric nature), but it is disheartening that such broad principles have not yet emerged for Cl− channels. Of the Cl− channel families we know, there are few, if any, obvious common principles except that Cl− channels are rather non-selective among anions. It is even difficult to make an unambiguous statement about how many families of Cl− channels currently are known. The simple statement is that there are five Cl− channel families: ligand gated anion channels, CFTR, ClCs, bestrophins, and anoctamins. However, of the nine mammalian ClC chloride “channels”, only four are actually channels; the others are Cl−:H+ exchangers. And, although there is strong evidence that bestrophins are Cl channels, some nagging data seems inconsistent with that conclusion (41). Two members of the recently identified anoctamin family have been shown clearly to be Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, but some of the others may not serve the same function (42). And, CFTR is a channel that looks like a transporter and has an excessively complicated energy-consuming gating mechanism (37). In addition to these major Cl− channel families, there are the proteins that are often not discussed in polite conversation, most notably the CLCA (Ca2+-activated Cl− channel) family and the CLICs (Chloride Intracellular Channels). In addition, some members of the SLC26 family of anion transporters (SLC26A7, SLC26A9) may be Cl− channels (43) and certain members of the glutamate transporter family can also function as Cl− channels (44–46). Figure 2 shows the kinds of Cl− channels that have been identified biophysically and their molecular counterparts.

Figure 2. Relationship of Biophysically Identified Cl− channels to genes.

Various kinds of Cl− channels that have been described in native cells by electrophysiological analysis are shown at the left. Candidate gene families are shown on the right. Lines show proposed relationships between the native channels and candidate genes. In many cases, a biophysically identified channel has been linked to multiple genes.

The ClC family

ClC proteins form a family of Cl− transport proteins that are expressed in nearly all phyla. These proteins may be separated into two functional groups: voltage-gated chloride channels, and Cl−:H+ exchangers (Figure 3). While evolutionarily these proteins are very similar, the mechanisms by which they perform their functions are very different. The functional unit of the ClC protein family is a homodimer, although heterodimers can form (47). In mammalian systems, ClC proteins mediate Cl− flux across the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes in most cell types and participate in maintenance of resting membrane potential, cell volume regulation, and acidification of intracellular compartments such as endosomes and lysosomes (48).

Figure 3. Ion flux through a single subunit of a ClC protein.

A common architecture (far left) is able to accommodate ion channel activity (upper panels), or Cl−:H+ exchange (lower panels). For ClC channels, proton entry into the permeation pathway is driven by a change in membrane potential, causing protonation of the conserved fast gate glutamate, leading to channel opening and passive Cl− diffusion. For ClC transporters, proton entry is driven by the pH gradient. Protons are transported via an internal proton transfer site and the conserved gating glutamate, leading to the exchange of 2 Cl− ions per proton.

There are four mammalian ClC proteins (ClC-1, -2, -Ka, and -Kb) that act as voltage-gated anion channels (not transporters) at the plasma membrane. The canonical ClC channel protein, ClC-0, was cloned from the electric organ of the Torpedo electric ray. ClC channels generally display a halide selectivity sequence of Cl− > Br− > I−, and have low cation permeability. ClC channels are homodimeric, with single protopore conductances of 10, 1.5, and 3 pS for ClC-0, -1, and -2, respectively (48). In addition to being activated by changes in membrane potential, ClC channels are also modulated by intracellular and extracellular [Cl−] and pH (49). pH regulates the channel by protonation of the fast gate, while regulation by [Cl−] may reflect the voltage-dependent binding or entry of the permeant ion into the channel.

It has recently come to light that some ClC proteins (ClC-3, -4, -5, -6, and -7 and the bacterial ClCs) mediate Cl−:H+ exchange rather than voltage-dependent anion channel activity (Figure 3). Unlike their channel counterparts, the exchanger subtypes are generally found on intracellular membranes. ClC transporters mediate the exchange of two Cl− ions for a single proton (50). Iyer and coworkers showed that the bacterial ClC exchanger is involved in extreme acid resistance (51). Indeed, the mammalian ClC proteins play a role in acidification of endosomes and lysosomes (52–55). Hepatocytes from ClC-3 knock-out mice have impaired endosomal acidification and Cl− accumulation (56). Interestingly, ClC-3 has been shown to be regulated both by CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation and by inositol (3,4,5,6)-tetrakisphosphate, which can alter endosomal pH (57, 58) Similarly, disruption of ClC-4 expression is associated with alkalinization of endosomal pH (59). Loss-of-function mutations in ClC-5 result in Dent’s disease, a syndrome characterized by kidney stones, proteinuria, and hypercalciuria. ClC-5, which is present on the plasma membrane and throughout the endocytic pathway, co-localizes with the proton pump in kidney cells (60). Endosomes from ClC-5 knock-out mice are acidified at a significantly lower rate than those of wild-type mice (61). There is some debate whether ClC-7 is involved in lysosomal acidification. Although Mindell’s lab finds that ClC-7 is the major Cl− counterion pathway in lysosomes and plays a role in lysosomal acidification (53), Thomas Jentsch’s lab has found that knockout of ClC-7 in mice does not alter lysosomal acification although it does alter lysosomal enzyme levels and produces neuronal degeneration (62). In addition to affecting endosomal acidification ClC transporters can influence other vesicular contents, notably zinc. In PC-12 cells ClC-3 channels functionally interact with the ZnT-3 zinc transporter modulate vesicular zinc stores (63).

A thin line between channels and transporters

Many questions exist about how ClC proteins having similar architecture are able transport Cl− across cell membranes by two very different mechanisms. It has recently been proposed by Lísal and Maduke that ClC-0 is a “broken” transporter (64). Early work showed that ClC-0 gating was a non-equilibrium process in which the channel preferentially cycled through gating states (65). This asymmetry was also shown to be dependent on the electrochemical gradient for Cl−. Lísal and Maduke showed that the gating cycle could be altered by changing the proton gradient when the Cl− electrochemical gradient was kept constant. Thus the asymmetry of ClC-0 gating is driven by the proton gradient, and not the gradient for Cl−. These authors suggest that this is remnant of evolution of ion channels from an ancestral transporter (64, 66). This idea is strengthened by data that other ClC channels show pH-dependent changes in activity. ClC-2 is activated by moderate acidification, but inhibited by strong acidification of the extracellular solution (67). Sepulveda and colleagues identified an extracellularly facing histidine, H532, that leads to channel closure when protonated. The H532F mutation abolishes acidification-dependent channel inhibition and the voltage-dependence of activation is imparted by voltage-dependent protonation of the gating glutamate. Thus, even in the ClC proteins that are bona-fide channels, protons play a crucial role in channel gating.

The structural differences between the channel and transporter subtypes seem surprisingly small. The intracellular proton transfer site, which is a glutamate in all ClC transporters, is valine in ClC channels (68). Interestingly, the location of the intracellular proton site is located away from the presumed Cl−conduction pathway, suggesting there may be a separate H+ conduction pathway (Figure 4D). Miller’s group has also been able to engineer a Cl− selective “channel” from the E. coli ClC by mutating the gating glutamate together with Y445, which forms part of the most external Cl− binding site (69). The flux rates of these mutants were inversely proportional to the side chain volume of the replacement residue, i.e channels with smaller side chains displayed higher flux rates. The close link between channel and transporters is further supported by mutagenesis data showing that when the Arabidopsis ClC-a residue involved in nitrate/chloride selectivity (P160) replaces the corresponding serine in ClC-0 (S123P), ClC-0 becomes more permeable to nitrate (70). Thus, only very small changes are required to evolve selective chloride transport from a ClC transporter, although evolution of finely tuned gating mechanisms is likely to be much more complex.

Figure 4. ClC protein structure.

(A). Membrane topology of a ClC protein. Each ClC protein is composed of two identical subunits containing 18 helical domains per subunit. Blue: CBS domains. Green: membrane segments. Re-drawn from (75). (B) Crystal structure of the S. Typhimurium ClC protein shown from the side. One subunit is shown in blue, while the other is shown in green. Bound chloride ions are shown as yellow spheres. Residues comprising the selectivity filter (S106, E1148, and Y445, and the intracellular proton binding site E203 are shown as red spheres (C). Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of ClC-0. (D) The proposed Cl− and H+ conductance pathways of a single subunit are illustrated with the selectivity filter and intracellular proton sites shown in stick representation. Some helices have been removed for clarity. Images in B–D were generated using Pymol based in the PDB entries 1KPL (B,D) and 2D4Z (C)

Architecture of ClC proteins

Prior to the cloning of ClC-0, studies performed on the voltage-dependent chloride conductance from Torpedo electroplax suggested that the functional unit of this protein contained two chloride conductance pathways (71). After the cloning of ClC-0, the functional oligomeric structure of this protein was unambiguously shown to be homodimeric, with each protopore possessing a chloride conduction pathway (72, 73). Single channel recordings of ClC-1 and ClC-2 suggest a similar dimeric structure for ClC-1 and ClC-2 (21, 74). Each protopore is independently controlled by a fast gate located within the ion permeation pathway, while both pores are controlled simultaneously by a slow gate (48). Closure of the slow gate leads to channel closure for seconds, while the fast gates operate in milliseconds.

In 2002, the high resolution crystal structures of two bacterial ClC proteins, from S. typhimurium and E. coli, were solved by Rod MacKinnon’s lab (75). Both of the bacterial ClC proteins formed homodimeric functional units, with both the N- and C-termini of each monomer being cytosolic (Figure 4A,B). These structures also revealed that the membrane topology was much more complicated than originally proposed; each subunit contained 17 intra-membrane helices (Figure 4A). This basic topology is thought to be conserved throughout the ClC family as shown for ClC-0 (76) and ClC-2 (77).

Despite the fact that the bacterial proteins are not channels, but rather Cl− : H+ antiporters, the crystal structures have revealed the Cl− conductance pathway within each subunit by the presence of three Cl− ions bound within each pore. The external binding site, Sext, may be occupied either by Cl−, or the side chain of the conserved glutamate residue E148, which is the primary molecular determinant for fast gating (75, 78, 79). When E148 occupies Sext, the permeation pathway is blocked. MacKinnon and colleagues suggested that Cl− ions compete with E148 for the occupation of this site, imparting the [Cl−]ext dependence of gating observed for many of these channels (80). Mutation of this glutamate residue in every ClC tested has led to channels that lack a fast-gating; single channel records of E166A-ClC-0, for example, only rarely show transitions between two distinct open states; it seems both protopores are always open together (79). Mutation of this residue in ClC transporters leads to the uncoupling of Cl− : H+ exchange. This suggests that this residue is an essential determinant of ClC protein function, and thus has been termed the “gating” glutamate.

The intracellular C-terminal domains of mammalian ClC proteins are larger than those of the bacterial counterparts and are likely to be involved in channel gating or regulation. Each C-terminal domain contains two cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) domains, which interact with each other within a subunit, and with other CBS domains in the partner subunit (81, 82). The crystal structures of the C-terminal domains of three ClC proteins (ClC-0, ClC-Ka, and ClC-5) have recently been solved. They all adopt similar folds (Fig. 4C). Evidence for dimerization has also been provided for the C-terminal domains of ClC-Ka and ClC-0 as well (81, 83).

The crystal structure of the ClC-5 CBS domains showed that ATP was coordinated at the CBS1/CBS2 interface(84). However, this does not seem to be a common feature of ClC proteins, as neither ClC-0 nor ClC-K have been shown to bind nucleotides. ClC-1 and ClC-2 gating is affected by ATP by a mechanism that requires the CBS domains (85–87). ClC-1 is inhibited by intracellular ATP and this inhibition is enhanced by intracellular acidification, suggesting a possible mechanism for muscle fatigue (85, 86, 88). Although, Zifarelli and Pusch could not replicate these results using inside-out patches from Xenopus oocytes (87), it has been suggested that this is because inhibition of ClC-1 by ATP depends on its oxidation state; ATP only inhibits reduced channels (89). These data lead to the reasonable conclusion that the CBS domains of ClC-1 coordinate ATP, and that these domains may be an essential domain for ClC protein modulation by intracellular factors. Mutations in the C-terminal CBS domains have been shown to alter both fast and slow gating.

Anoctamins: the Newest Cl− Channel Family

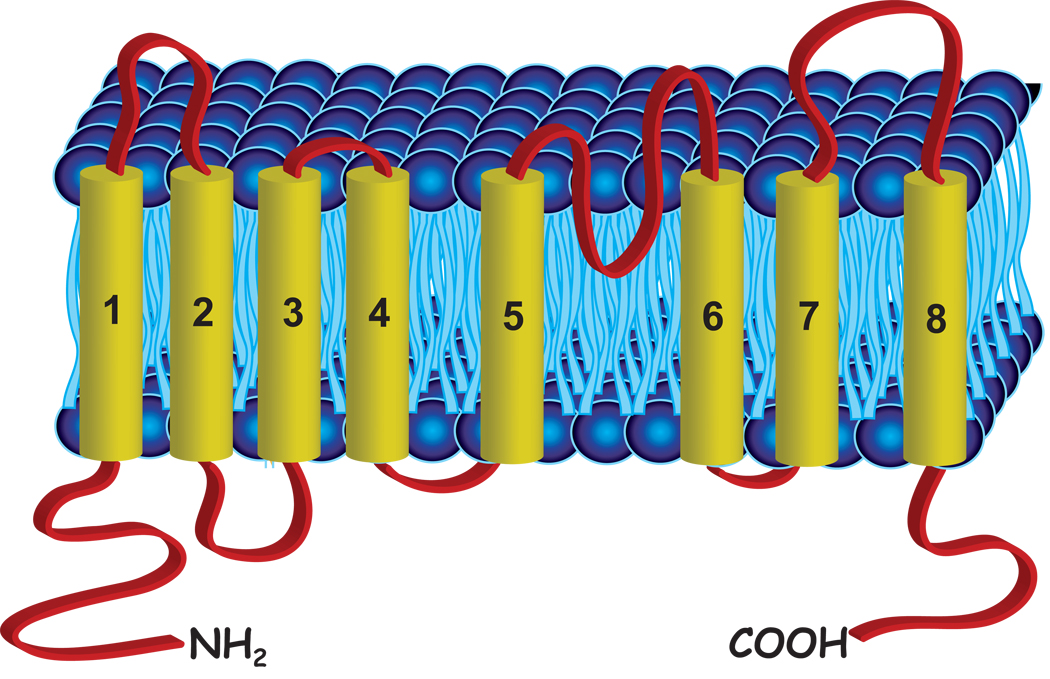

The Anoctamin family (originally called TMEM16) was recognized several years ago as the result of bioinformatic analysis of sequence databases (Figure 5) (90), but it was not until late 2008 that it was shown that Ano1 encoded a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) (91–93). The anoctamin family has 8 putative membrane-spanning domains, and is comprised of 10 members. To date, it has been shown clearly that Ano1 and Ano2 generate Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (42, 91–95). It is not yet known whether other members of this family are also CaCCs, but the degree of conservation within the predicted transmembrane domains suggests that other anoctamins may also function as Cl− channels.

Figure 5. Cartoon of Ano1 transmembrane topology.

(A) Anoctamins are thought to have 8 transmembrane domains and a re-entrant loop between transmembrane domain 5 and 6 with cytoplasmic C- and N- termini. The structure is based on experimental studies on Ano7 from (103). (B) Alignment of the putative pore domain of Ano1 and Ano2 showing conserved basic amino acids at positions 621, 645, and 668 (numbering relative to Ano1 sequence used by Yang et al. (93).

Expression of Ano1 and Ano2 in various cell types induces Cl− currents with biophysical properties similar to native CaCCs. The calcium sensitivity and voltage dependence of Ano1 is similar to endogenous CaCC’s, with an EC50 of 2.6 µM at −60mV (93). The Ca2+ sensitivity decreases with depolarization (93), much like endogenous CaCC currents in Xenopus oocytes (96). Furthermore, the current is strongly outwardly rectifying and is inhibited by high Ca2+ (92, 93). Xenopus Ano1 is similar to native Xenopus oocyte CaCCs, as it exhibits outwardly rectifying current at low intracellular Ca2+, but displays a linear current-voltage relationship at higher intracellular Ca2+ (92). Ano2 is also outwardly rectifying, but activates more quickly than Ano1 and has a significantly lower apparent Ca2+ affinity (94, 95). The anion selectivity sequence of Ano1 and Ano2, (NO3− > I− > Br− > Cl− > F−) is the same as those of native CaCCs (91–94), as is the pharmacology. Ano1 and 2 are blocked by traditional chloride channel blockers including DIDS (4,4’-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2, 2’-disulfonic acid), NPPB(5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid), tamoxifen, and NFA (niflumic acid) (93, 94). Although Pifferi et al. show that Ano2 is blocked by DIDS (94), Stohr and colleagues find the opposite (95).

Ano1 and Ano2 are the first CaCC candidates shown to be activated by G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) stimulation. When mAno1 or mAno2 is co-transfected with GPCR’s that raise intracellular Ca2+ in HEK 293T cells, GPCR activation induces Ano1 currents (93, 94). GPCR coupled activation of a CaCC resembling Ano1 is observed in the pancreatic cell line CFPAC-1 in response to purinergic receptor activation. This current is abolished in cells transfected with Ano1 siRNA (91). Similarly, co-expression of Xenopus Ano1 with the M1 muscarinic ACh receptor induces Cl− currents in response to CCh (92). Ano1 also mediates physiological responses of CaCCs in vivo. Treatment of mice with Ano1 siRNA reduces the rate of pilocarpine-induced salivary secretion (93). Ano1 may also be responsible for facilitating other CaCC-mediated physiological responses as it is expressed in a variety of epithelial tissues known to have robust CaCCs, such as bronchioles, mammary gland, and pancreas (91, 93, 97, 98). Ano1 very likely contributes to the CaCC in tracheal epithelium. Mice homozygous for a null allele of Ano1 exhibit a greater than 60% reduction in UTP-stimulated CaCC activity compared to wild type mice (99).

Ano2 is expressed in photoreceptors and olfactory sensory neurons, both of which possess large CaCCs. In photoreceptors, Ano2 is present in synaptic membranes where it co-localizes with a presynaptic protein complex containing the adaptor proteins PSD95 (with which it interacts directly via its C-terminal domain), VELI3, and MPP4 (95). Through this presynaptic scaffold, Ano2 appears to be tethered to membrane domains along the photoreceptor terminals, where its function may be to regulate synaptic output. Ano2 likely has important roles in olfactory signal transduction as well (100). In the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons, a Ca2+-activated chloride conductance serves as an amplification step that accounts for the majority of odorant-induced depolarizing current. Ano2 may be a major component of the olfactory CaCC, as it is present in the membranes of olfactory cilia and has channel properties similar to native olfactory CaCCs. Ano2 and native CaCCs share similarities in channel rundown, halide permeability, Ca2+ sensitivity, and single-channel conductance. There are, however, differences in channel inactivation kinetics. Unlike the native olfactory CaCC, steady secondary decline of Ano2 current at positive holding potentials is minimal. Therefore, while Ano2 is the probable pore-forming subunit, the presence of an additional regulatory subunit cannot be excluded. Best2 has also been proposed as a candidate olfactory CaCC, but displays channel properties not consistent with those of native currents, differing in calcium sensitivity, inactivation kinetics, and single-channel conductance (101).

Anoctamin Structure and Function

The anoctamins do not share significant sequence homology with other known ion channel families. However, they do share distant primary sequence homology with a family of transmembrane proteins of unknown function, the Transmembrane Channel Like (TMC) family (102). While anoctamins are found in all eukaryotic kingdoms, they are best represented in higher vertebrates. Mammalian anoctamins have 10 gene members that are well conserved across species and are predicted to have similar topologies. Hydropathy analysis of anoctamins predicts an eight transmembrane structure with cytoplasmic N and C-termini (90). The transmembrane toplogy of Ano7 has been experimentally verified using epitope tag insertion and N-glycosylation site accessibility (103). Mutational analysis of Ano1 places the putative pore region in a highly conserved region between transmembrane domains 5 and 6 (TM5 and TM6). This region is predicted to form a re-entrant loop and contains three positively charged residues that are conserved in most isoforms (R621, K645, and K668). When these residues are mutated to a negatively charged residue, glutamate, Ano1 shows a marked increase in cation permeability relative to anion permeability. Furthermore, neutralization of basic amino acids in TM5 and TM6 that flank the re-entrant loop alter channel gating and voltage-dependence (91). To further examine the importance of this region in the ion conduction pathway, Yang et al. (93) determined the accessibility of cysteines in this region to membrane-impermeant thiol reagents. MTSET completely blocks the wild type Ano1 current, but has no effect on mutants in which the three cysteines in the re-entrant loop are replaced with alanines (C673A, C678A, C683A). These data suggest that the region encompassing TM5 and TM6 is a pore-forming region and an important determinant of the permeation pathway in Ano1.

Ano1 does not have any apparent Ca2+-binding sites such as EF hands or IQ-domain CaM binding sites. However, it does have a structure that is reminiscent of the Ca bowl of the large-conductance Ca-activated K channel (BK) that is known to be involved in Ca binding. This domain is located in the first intracellular loop and has 5 consecutive glutamic acid residues. It is likely that this region will turn out to have at least one of the Ano1 Ca binding sites.

Anoctamins exhibit multiple alternatively-spliced forms. Ano1 has at least 4 alternatively spliced exons encoding intracellular regions of the protein (91). Splice variants a, ac, abc, and abcd produce currents when expressed in HEK cells while the variant lacking these segments is not functional. Ano7 has two splice variants: a 933 amino acid plasma membrane protein, and a shorter 179 amino acid cytosolic-protein (104). A Genbank search reveals that many of the anoctamins also have short isoforms, suggesting that they may also have non-channel functions.

Possible Roles of Anoctamins in Development and Cancer

Mutations in Ano5 are responsible for a rare autosomal dominant skeletal syndrome, gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia (GDD). Mutations in C356, a conserved cysteine in the first extracellular loop of Ano5, result in bone fragility and abnormal bone mineralization (105, 106). Ano5 resides predominantly in intracellular membrane vesicles and shows a high level of expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues, as well as growth-plate chondrocytes and osteoblasts in bone (107). The function of Ano5 is unknown, but evidence suggests that it may play a role in the development of the musculoskeletal system (107).

Mice homozygous for a null allele of Ano1 display ventral gaps in the tracheal cartilage rings and die within the first month of life due to these abnormalities (97). It is proposed that this defect is due to the improper organization of mutant tracheal epithelium and/or trachealis muscle where Ano1 is expressed. Other anoctamin family members are expressed in several sites of morphogenetic events during development and may have important roles in development as well (98, 108).

Anoctamins attracted the interest of cancer biologists even before they were identified as ion channels because they are up-regulated in a variety of cancers. This is reflected in the various other names for Ano1: TAOS2 (tumor amplified and overexpressed sequence), ORAOV2 (oral cancer overexpressed), and DOG-1 (discovered on GIST-1, a gastrointestinal stromal tumor) (see (42)). An antibody against DOG-1 has been proposed as the most sensitive method for detecting gastrointenstinal stromal tumors (109). Although Ano1 is upregulated in tumors, no mutations in Ano1 are linked to carcinogenesis (110). The precise biological role of anoctamins in cancer is unclear, but they may have an important role in cell proliferation and the progression of tumors to metastatic cancers.

Ano7 (also called NGEP and D-TMPP) was initially found in a “Guilt-by-Association” search for genes whose expression patterns mimic those of known disease-associated genes (111). Walker et al. examined the coexpression patterns of 40,000 human genes and identified 8 novel genes that had the highest association with known prostate tumor genes. They concluded that of the 40,000 most-abundant human genes, 8 (including Ano7) are most closely linked to known prostate cancer genes. It remains unclear, however, how Ano7 may function in prostate cancer. It has been reported that Ano7 is expressed on the apical and lateral membranes of normal prostate and prostate cancer cells and is concentrated at cell-cell junctions of the LNCaP prostate cancer cells (112). Over-expression of Ano7 in LNCap cells promotes association of LNCap cells, which can be abolished with RNAi targeted for Ano7. These studies imply that Ano7 may be responsible for cell contact-dependent interactions in prostate epithelial cells.

It has been known for some time that the activity of Cl− channels in ascidian embryos and B-lymphocytes correlate with the cell cycle (113–116). For example, in ascidian embryos, a Cl− current activates cyclically during mitosis as a result of a dephosphorylation event that is controlled by the cell cycle clock. Because these Cl− channels are also regulated by changes in cell volume, they may be related to the volume-regulated anion channels (VRAC) that are important in compensatory responses of cells to changes in cell volume (117, 118). Cell-cycle dependent Cl− channels are involved in coupling cell volume/shape changes that occur during cell division (119, 120). Recent studies have further implicated Cl− channels in cell proliferation in a variety of cell types (121–126). Recently, it has been suggested that Cl− plays a role in controlling the G1/S phase checkpoint by regulating expression of p21, an inhibitor of cyclin dependent kinase (126) and in the earliest stages of apoptosis (127). In most of these studies, the molecular identities of the channels involved are not known, but anoctamins are intriguing candidates. For example, a Drosophila Ano8/Ano10 ortholog called Axs (abberant x-segregation) is necessary for normal spindle formation and cell cycle progression. Axs co-localizes with the enoplasmic reticulum and is present in membranes associated with the meiotic spindle in early embryos. A dominant mutation in Axs results in defective segregation of homologous achiasmate chromosomes, defects in spindle formation, and cell cycle (128).

Bestrophin Function is Controversial

Bestrophins were first proposed to be Cl− channels in 2002 by Jeremy Nathan’s lab (129) (reviewed in (41, 130)). In most mammals, there are 4 bestrophin genes. There is a wealth of very convincing data that bestrophins function as Cl− channels. However, because they apparently can also regulate other ion channels and because there is conflicting data in the literature about their expression patterns and function, skepticism remains about their physiological roles (41).

First, there is disagreement over which tissues express bestrophins (130). For example, mBest2 has been proposed to be the CaCC in olfactory epithelium (101), but other investigators have reported that mBest2 is not expressed in this tissue (131). Similarly, RNAi knockdown of mBest1 and mBest2 in mouse airway results in a significant decrease in CaCC (132–134) , but Marmorstein does not find that mBest1 is expressed in these tissues (130). Reports that bestrophins are expressed in pancreas (135) and salivary gland (136) require confirmation.

Second, the role of Best1 in Best vitelliform macular degeneration (BVMD) is puzzling (sidebar). BVMD is defined clinically by a decreased electro-oculogram light peak (LP), which is thought to be caused by a defective CaCC in the basolateral membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Over 100 disease-causing mutations have been found, many of which cause Cl− channel dysfunction(41, 129, 137–139). However, knockout of mBest1 in mice does not produce ocular disease, and CaCCs are normal in the knockouts (140). Thus, it seems clear that mBest1 is not the CaCC in mouse RPE, despite the fact that mBest1 does apparently function as a CaCC when expressed heterologously (141). Furthermore, there are several different ocular diseases that are caused by bestrophin mutations, each having a unique phenotype (Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, adult onset macular dystrophy, autosomal dominant vitreochoidopathy, autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy, and canine multifocal retinopathy (130)). Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (142) appears to be caused by an absence of functional Best1 protein, while BVMD is dominantly inherited. This suggests that BVMD is not caused simply by a loss-of-function of Best1, but rather is caused by a gain-of-function. However, it is not known what this gain-of-function might be. In addition to functioning as a chloride channel, there is evidence that hBest1 can also act as a regulator of other channels, specifically voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (143, 144). Also, it has been found that bestrophins are highly permeant to HCO3, raising the possibility that physiologically bestrophins function as HCO3 channels (16). Based on these and other data, it has been proposed that Best1 plays a role in intracellular Ca2+ and pH homeostasis (Figure 6) (130), which may produce defective phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments by retinal pigment epithelial cells (41, 130).

Figure 6. Regulation of hBest1.

hBest1 is regulated directly by Ca2+ binding to a region immediately after the last transmembrane and by PKC-dependent phosphorylation at S358 in the C-terminus. In addition, hBest1 can regulate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels via an SH3-binding domain in the C-terminus. Effects of cell volume on hBest1 are thought to be regulated by phosphorylation - dephosphorylation of S358 via a protein phosphatase that is likely to be protein phosphatase 2A via a pathway that may involve ceramide.

Third, the role of mBest2 in the ciliary body of the eye is paradoxical. mBest2 is expressed in the nonpigmented epithelium which participates in secretion of aqueous humor (131, 145). mBest2 knockout mice show a lower intraocular pressure (IOP) (131, 145), as one might expect if mBest2 is the apical Cl− channel that drives fluid secretion in this tissue (146). Paradoxically however, the inflow and outflow of aqueous humor are both enhanced in mBest2 knockout resulting in overall lower IOP (145). These data contradict the supposition that mBest2 is involved in aqueous humor production. It is unknown how mBest2 affects both inflow and outflow of aqueous humor since it is only expressed in the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium.

Fourth, there are conflicting reports about the nature of the Best3 current. Qu et al. (147) have reported that wild type mBest3 elicits a tiny, inwardly-rectifying current at physiological voltages when it is expressed heterologously in HEK cells. This is similar to the hBest3 current expressed in HEK cells (148). In contrast, it has been reported that mBest3 cloned from heart exhibits large time- and voltage-independent currents (149). The amino acid sequence of this clone is identical to the one used by Qu et al. (147), so the reasons for the different properties remain unknown. To complicate matters, Matchkov et al. (150) have proposed that mBest3 is a cGMP-dependent Ca2+-activated current in vascular smooth muscle cells. RNAi knockdown of Best3 in A5r7 vascular smooth muscle cells reduces a cGMP-dependent Ca2+-activated current that has time- and voltage-dependence much like the current described by O’Driscoll et al. (149). It is possible that in native cells, Best3 associates with another subunit that confers cGMP-dependence that is not present in HEK cells.

Recently, several papers have suggested the possibility that bestrophins may play roles in development and tumorigenesis. For example, Xenopus Best2 is expressed at the edge of the blastopore lip including the organizer (151). Ectopic expression of xBest2 causes defects in dorsal axis formation and in mesodermal gene expression during gastrulation. Furthermore, indirect evidence suggests that mBest2 plays a role during differentiation and growth of axons and cilia in the olfactory system (152). The expression of mBest2 correlates with neuronal regeneration of olfactory neurons. Best1 is upregulated in fast growing colonic cancer cells (153), and expression of Best1 in mouse renal collecting duct cells causes an increase in cell proliferation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (154). These data are correlative, but deserve further consideration.

Bestrophins are Regulated by Various Mechanisms

Calcium

The bestrophins that have been tested are activated by Ca2+ with a Kd of about 200 nM (41, 148, 155, 156). hBest4 and dBest1 in excised patches are activated by Ca2+ without involvement of any diffusible second messengers(156, 157), suggesting Ca2+ binds directly. Using 45Ca overlay, Xiao et al. (155) found the purified hBest1 C-terminus directly binds Ca2+. The Ca2+ binding site was found to include a cluster of acidic amino acids and an EF-hand-like structure located in the C-terminus immediately following the last transmembrane domain. Mutations in the acidic cluster abolish channel activity, presumably by affecting Ca2+-dependent gating, although direct evidence for this is lacking because of the non-functionality of the mutant channels. Immediately following the acidic cluster is a structure that resembles an EF-hand. The D312G mutation in the EF-hand reduces Ca2+ affinity by ~20 fold, confirming that the EF-hand is involved in Ca2+ sensing. The Ca2+ binding site is highly conserved among all the bestrophins, supporting the idea that other bestrophins are also directly activated by Ca2+ binding to this site. Kranjc et al. have proposed that the acidic cluster and the associated EF-hand resemble the Ca2+-binding domain of thrombospondin (158).

Recently, Qu et al. (159) used FRET and pull-down assays to examine the hypothesis that activation of hBest1 depends upon the interaction of the N- and C-termini. They found that in wild-type channels, the N- and C- termini interact, but disease-causing mutations in the N-terminus or the Ca2+-binding domain of the C-terminus reduce this interaction. This suggests that hBest1 activation involves binding of Ca2+ to the C-terminus followed by interaction with the N-terminus of the same or adjacent subunit.

Phosphorylation

Adjacent to the Ca2+ binding domain there is another regulatory domain that was first identified in Best3. Wild type Best3 expressed in HEK cells produces very small currents in response to high intracellular Ca2+ at physiological voltages. Truncation of the protein at amino acid 353 (353X), which does not affect the Ca2+ binding site, produces a large Ca2+-activated chloride conductance (147). The region responsible for the reduced current is an autoinhibitory domain that includes the sequence 356IPSFLGS362 (147). The SFXGS domain is present in all vertebrate bestrophins, but appears to have different functions in different paralogs. Mutation of this region in Best2 results in an augmentation of current amplitude (147). In hBest1, this region is involved in regulation of the channel by phosphorylation. The Ca2+ activated current is abolished by deleting the amino acids beyond 353, though the Ca2+ binding site is still intact (155). By successive deletions and mutations, a regulatory domain in hBest1 was found to include amino acids 350–390. This region is not only critical for Ca2+-dependent channel activation, but is also responsible for Ca2+-dependent channel rundown. Channel rundown is mediated through phosphorylation of S358 (Xiao et al., submitted). Several potential phosphorylation sites exist in hBest1 (41). hBest1 can incorporate 32P when transfected into RPE-J cells, and can be coimmunoprecipitated with PP2A from human and pig RPE cells (160). Bestrophin is also reported to be activated by nitric oxide in Calu-3 cells via a cGMP-dependent phosphorylation pathway (133). Furthermore, mBest3 is essential for PKG-dependent Ca2+ activated chloride current in vascular smooth muscle (150).

SH3-binding domains

Interestingly, an SH3 binding domain (330–350) lies between the Ca2+ binding site and the SFXGS regulatory domain in hBest1(144). This domain directly binds to the β subunit of CaV channels to regulate CaV1.3. The residues P330 and P334 which are unique in hBest1 but are not present in mBest1, mBest2, and mBest3, are critical for regulation of Ca2+ channel since mutation of both prolines abolishes this effects. The regulatory effect of hBest1 on CaV channels has been demonstrated only in transfected cells to date, so the physiological relevance is not established.

Cell Volume

In addition to being activated by Ca2+, bestrophins can be regulated by changes in cell volume. The volume-regulated Cl− current in Drosophila S2 cells is knocked down by dBest1 siRNA, and rescued by transfection with both wild type dBest1 and a mutant dBest1 with altered ion permeability (161, 162). This supports the idea that the native volume-regulated anion channel in S2 cells is dBest1. In addition, hBest1 and mBest2 currents expressed in HEK cell lines are inhibited by hyperosmotic solutions (163). However, it is clear that neither Best1 nor Best2 are volume-regulated anion channels in mammals, because mBest1/mBest2 knockout mice have normal volume-regulated Cl− currents (162). Nonetheless, it is unclear whether bestrophins function as Ca activated chloride channels or volume regulated chloride channels under physiological and pathological conditions.

Summary Points

Until recently, the role of Cl− in biological systems was not highly appreciated, but once it was realized that Cl− was actively transported in cells and that dysfunction of Cl− transport produced human disease, interest in Cl− blossomed.

Chloride may be a kind of second messenger in cells: its concentration is regulated by channels and transporters, its intracellular concentration is dynamic on both short and long time scales, it is transported into and out of intracellular organelles, and it binds to and regulates the function of a variety of proteins.

Dysfunction of Cl− transport has been shown to be associated with over a dozen human diseases.

The ClC family is comprised of 9 proteins in mammals with very similar molecular architecture, but some of these proteins are transporters and others are channels. They function both at the plasma membrane and in intracellular membranes.

Anoctamins (TMEM16) are the newest family of Cl− channels with ten members. Two of these are highly favored candidates for Ca-activated Cl channels, but the functions of the other 8 members is not known.

There is a wealth of evidence showing that bestrophins are Cl−channels and that some are regulated by Ca2+ and cell volume, but their physiological role remains enigmatic.

Future Issues

Does luminal Cl− concentration play a role in endosomal trafficking and function by regulating endosomal protein function?

What is the precise role of Cl− channels and transporters in regulating intravesicular pH in endosomes and lysosomes?

What are the mechanisms of proton transport in the ClC transporters and how is proton transport coupled to Cl− transport?

Are all anoctamins Cl− channels, and if so, how are they regulated and what is their function?

How is the anion channel function of bestrophins related to various retinopathies?

Sidebar

A puzzle: Is Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy (BVMD) a Chloride Channelopathy?

Supporting data:

A Characteristic feature of BVMD is a diminished light peak of the electro-oculogram.

The Light Peak in cat and gecko is mediated by a CaCC located in the basolateral membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

Bestrophin-1 is located in the basolateral membrane of the RPE.

Human Bestrophin-1 is clearly a Cl− channel. Bestrophin mutations affect Cl− conductance and Ca2+ sensitivity.

BVMD-causing mutations in human Bestrophin-1 produce defective Cl channel function in heterologously expressed channels.

Data against:

Knockout of mBest1 in mice has no effect on CaCC currents in mouse RPE cells.

RPE CaCC currents are probably mediated by an anoctamin.

Knockout of mBest1 does not diminish the Light Peak in mouse.

Over-expression and knockdown of bestrophin in rat RPE does not have the expected effects if bestrophin is a Cl− channel whose function is abolished by BVMD mutations.

Retinopathies that are likely to be caused by Best-1 null mutations (autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy and canine multifocal retinopathy) produce different phenotypes than point mutations that cause BVMD.

Some mutations produce BVMD without affecting the Light Peak.

Terms and Definitions

- CaCC

Ca2+-activated Cl− channel activated by increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+

- Channel

a protein that forms a pore across cell membranes and conducts ions passively downhill.

- Channelopathy

a human disease caused by a dysfunction of an ion channel, usually the result of a genetic mutation

- Cystic fibrosis

a common genetic disease caused by dysfunction of the Cl− channel CFTR.

- Myotonia congentia

an inherited disease characterized by muscle paralysis and hyperexcitability.

- RNAi

interfering (or silencing RNA)

- Transporter

a protein that uses energy of one ion to transport another ion uphill.

- VRAC

volume-regulated anion channel activated by cell swelling

Acronyms

- BVMD

Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy, an inherited macular degeneration

- CaCC

Ca2+-activated Cl− channel activated by increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+

- CBS

cystathionine-β-synthase

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- ClC

9-gene family of chloride channels

- GDD

gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia

- HEK

human embryonic kidney cells

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- TM

transmembrane

- VRAC

volume-regulated anion channel activated by cell swelling

Contributor Information

Charity Duran, Department of Cell Biology, 615 Michael St., Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322.

Christopher H. Thompson, Division of Genetic Medicine, 2215 Garland Ave, 516 Light Hall, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37232

Qinghuan Xiao, Department of Cell Biology, 615 Michael St., Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322.

Criss Hartzell, Department of Cell Biology, 615 Michael St., Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322.

Literature Cited

- 1.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinaur Associates Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keynes RD. Chloride in the squid giant axon. The Journal of Physiology Online. 1963;169:690–705. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogben CA. Physiochemical aspects of hydrochloric acid formation. Am J Dig.Dis. 1959;4:184–193. doi: 10.1007/BF02231222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coombs JS, Eccles JC, Fatt P. The specific ionic conductances and the ionic movements across the motoneuronal membrane that produce the inhibitory post-synaptic potential. The Journal of Physiology Online. 1955;130:326–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinaur Associates Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinaur Associates Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1215–1284. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isomura Y, Sugimoto M, Fujiwara-Tsukamoto Y, Yamamoto-Muraki S, Yamada J, Fukuda A. Synaptically activated Cl− accumulation responsible for depolarizing GABAergic responses in mature hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2752–2756. doi: 10.1152/jn.00142.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuner T, Augustine GJ. A genetically encoded ratiometric indicator for chloride: capturing chloride transients in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;27:447–459. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berglund K, Schleich W, Krieger P, Loo LS, Wang D, et al. Imaging synaptic inhibition in transgenic mice expressing the chloride indicator, Clomeleon. Brain Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11068-008-9019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahle KT, Ring AM, Lifton RP. Molecular Physiology of the WNK Kinases. Annual Review of Physiology. 2008;70:329–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponce-Coria J, San-Cristobal P, Kahle KT, Vazquez N, Pacheco-Alvarez D, et al. Regulation of NKCC2 by a chloride-sensing mechanism involving the WNK3 and SPAK kinases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:8458–8463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802966105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu.Rev.Physiol. 2005;67:719–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart AK, Yamamoto A, Nakakuki M, Kondo T, Alper SL, Ishiguro H. Functional coupling of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange with CFTR in stimulated HCO3− secretion by guinea pig interlobular pancreatic duct. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1307–G1317. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90697.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shcheynikov N, Ko SB, Zeng W, Choi JY, Dorwart MR, et al. Regulatory interaction between CFTR and the SLC26 transporters. Novartis.Found.Symp. 2006;273:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Bestrophin Cl− channels are highly permeable to HCO3. AJP - Cell Physiology. 2008;294:C1371–C1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mumbengegwi DR, Li Q, Li C, Bear CE, Engelhardt JF. Evidence for a Superoxide Permeability Pathway in Endosomal Membranes. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:3700–3712. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02038-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lassegue B. How does the chloride/proton antiporter ClC-3 control NADPH oxidase? Circulation Research. 2007;101:648–650. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant SH. Cable properties of external intercostal muscle fibres from myotonic and nonmyotonic goats. The Journal of Physiology Online. 1969;204:539–550. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipicky RJ, Bryant SH, Salmon JH. Cable parameters, sodium, potassium, chloride, and water content, and potassium efflux in isolated external intercostal muscle of normal volunteers and patients with myotonia congenita. J Clin.Invest. 1971;50:2091–2103. doi: 10.1172/JCI106703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jentsch TJ, Steinmeyer K, Schwarz G. Primary structure of Torpedo marmorata chloride channel isolated by expression cloning in Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1990;348:510–514. doi: 10.1038/348510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch MC, Steinmeyer K, Lorenz C, Ricker K, Wolf F, et al. The skeletal muscle chloride channel in dominant and recessive human myotonia. Science. 1992;257:797–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1379744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinmeyer K, Ortland C, Jentsch TJ. Primary structure and functional expression of a developmentally regulated skeletal muscle chloride channel. Nature. 1991;354:301–304. doi: 10.1038/354301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pusch M, Steinmeyer K, Koch MC, Jentsch TJ. Mutations in dominant human myotonia congenita drastically alter the voltage dependence of the CIC-1 chloride channel. Neuron. 1995;15:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahlke C, Beck CL, George AL., Jr A mutation in autosomal dominant myotonia congenita affects pore properties of the muscle chloride channel. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1997;94:2729–2734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodgkin AL, Horowicz P. The influence of potassium and chloride ions on the membrane potential of single muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology Online. 1959;148:127–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutter OF, Noble D. The chloride conductance of frog skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology Online. 1960;151:89–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adrian RH, Bryant SH. On the repetitive discharge in myotonic muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1974;240:505–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Sant'Agnese PA, Darling RC, Perera GA, Shea E. Abnormal electrolyte composition of sweat in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas; clinical significance and relationship to the disease. Pediatrics. 1953;12:549–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinton PM. Chloride impermeability in cystic fibrosis. Nature. 1983;301:421–422. doi: 10.1038/301421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinton PM. Physiological Basis of Cystic Fibrosis: A Historical Perspective. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:3–22. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knowles M, Gatzy J, Boucher R. Relative ion permeability of normal and cystic fibrosis nasal epithelium. J Clin.Invest. 1983;71:1410–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI110894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989;245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science. 1989;245:1059–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.2772657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bear CE, Li CH, Kartner N, Bridges RJ, Jensen TJ, et al. Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cell. 1992;68:809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gadsby DC, Vergani P, Csanady L. The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature. 2006;440:477–483. doi: 10.1038/nature04712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan K, Kota KC, Cui G, Thompson CH, McCarty N. Evolutionary and functional divergence between CFTR and related ABC transporters. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806306105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doring G, Gulbins E. Cystic fibrosis and innate immunity: how chloride channel mutations provoke lung disease. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mall M, Grubb BR, Harkema JR, O'Neal WK, Boucher RC. Increased airway epithelial Na + absorption produces cystic fibrosis-like lung disease in mice. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:487–493. doi: 10.1038/nm1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartzell HC, Qu Z, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT. Molecular Physiology of Bestrophins: Multifunctional membrane proteins linked to Best Disease and other retinopathies. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88:639–672. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin / TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. The Journal of Physiology Online. 2009;587(10):2127–2139. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorwart MR, Shcheynikov N, Yang D, Muallem S. The solute carrier 26 family of proteins in epithelial ion transport. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:104–114. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schenck S, Wojcik SM, Brose N, Takamori S. A chloride conductance in VGLUT1 underlies maximal glutamate loading into synaptic vesicles. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:156–162. doi: 10.1038/nn.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vandenberg RJ, Huang S, Ryan RM. Slips, leaks and channels in glutamate transporters. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:51–58. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.1.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeFelice LJ, Goswami T. Transporters as channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:87–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.164816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki T, Rai T, Hayama A, Sohara E, Suda S, et al. Intracellular localization of ClC chloride channels and their ability to form hetero-oligomers. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:792–798. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zifarelli G, Pusch M. CLC chloride channels and transporters: a biophysical and physiological perspective. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;158:23–76. doi: 10.1007/112_2006_0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zifarelli G, Pusch M. The role of protons in fast and slow gating of the Torpedo chloride channel ClC-0. Eur Biophys J. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00249-008-0393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl- channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iyer R, Iverson TM, Accardi A, Miller C. A biological role for prokaryotic ClC chloride channels. Nature. 2002;419:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jentsch TJ. Chloride and the endosomal-lysosomal pathway: emerging roles of CLC chloride transporters. J.Physiol. 2007;578:633–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graves AR, Curran PK, Smith CL, Mindell JA. The Cl−/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature. 2008;453:788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature06907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Picollo A, Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheel O, Zdebik AA, Lourdel S, Jentsch TJ. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hara-Chikuma M, Yang B, Sonawane ND, Sasaki S, Uchida S, Verkman AS. ClC- 3 chloride channels facilitate endosomal acidification and chloride accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1241–1247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell J, Wang X, Zhang G, Gentzsch M, Nelson DJ, Shears SB. An expanded biological repertoire for Ins(3,4,5,6)P4 through its modulation of ClC-3 function. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1600–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alekov AK, Fahlke C. Anion channels: regulation of ClC-3 by an orphan second messenger. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R1061–R1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohammad-Panah R, Harrison R, Dhani S, Ackerley C, Huan LJ, et al. The chloride channel ClC-4 contributes to endosomal acidification and trafficking. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:29267–26277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hara-Chikuma M, Wang Y, Guggino SE, Guggino WB, Verkman AS. Impaired acidification in early endosomes of ClC-5 deficient proximal tubule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:941–946. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gunther W, Piwon N, Jentsch TJ. The ClC-5 chloride channel knock-out mouse - an animal model for Dent's disease. Pflugers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2003;445:456–462. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0950-6. [Review] [48 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kasper D, Planells-Cases R, Fuhrmann JC, Scheel O, Zeitz O, et al. Loss of the chloride channel ClC-7 leads to lysosomal storage disease and neurodegeneration. EMBO Journal. 2005;24:1079–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salazar G, Love R, Werner E, Doucette MM, Cheng S, et al. The zinc transporter ZnT3 interacts with AP-3 and it is preferentially targeted to a distinct synaptic vesicle subpopulation. Mol.Biol.Cell. 2004;15:575–587. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lisal J, Maduke M. The ClC-0 chloride channel is a 'broken' Cl−/H+ antiporter. Nat.Struct.Mol.Biol. 2008;15:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richard EA, Miller C. Steady-state coupling of ion-channel conformations to a transmembrane ion gradient. Science. 1990;247:1208–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.2156338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lisal J, Maduke M. Review. Proton-coupled gating in chloride channels. Philos.Trans.R.Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:181–187. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niemeyer MI, Cid LP, Yusef YR, Briones R, Sepulveda FV. Voltage-dependent and -independent titration of specific residues accounts for complex gating of a ClC chloride channel by extracellular protons. J Physiol. 2009;587:1387–1400. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Accardi A, Walden M, Nguitragool W, Jayaram H, Williams C, Miller C. Separate ion pathways in a Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:563–570. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jayaram H, Accardi A, Wu F, Williams C, Miller C. Ion permeation through a Cl-- selective channel designed from a CLC Cl−/H+ exchanger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11194–11199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804503105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bergsdorf EY, Zdebik AA, Jentsch TJ. Residues important for nitrate/proton coupling in plant and mammalian CLC transporters. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901170200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller C, White MM. Dimeric Structure of Single Chloride Channels from Torpedo Electroplax. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1984;81:2772–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Middleton RE, Pheasant DJ, Miller C. Homodimeric architecture of a ClC-type chloride ion channel. Nature. 1996;383:337–340. doi: 10.1038/383337a0. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ludewig U, Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. Two physically distinct pores in the dimeric ClC-0 chloride channel. Nature. 1996;383:340–343. doi: 10.1038/383340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Huan LJ, Garami E, Wang Y, Bear CE. Quaternary structure of the chloride channel ClC-2. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13838–13847. doi: 10.1021/bi001282i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Engh AM, Maduke M. Cysteine accessibility in ClC-0 supports conservation of the ClC intracellular vestibule. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:601–617. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramjeesingh M, Li C, She YM, Bear CE. Evaluation of the membrane-spanning domain of ClC-2. Biochem J. 2006;396:449–460. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dutzler R. Structural basis for ion conduction and gating in ClC chloride channels. FEBS Letters. 2004;564:229–233. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 2003;300:108–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1082708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen TY. Coupling gating with ion permeation in ClC channels. Science's Stke [Electronic Resource]: Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment. 2003;2003:e23. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.188.pe23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Markovic S, Dutzler R. The structure of the cytoplasmic domain of the chloride channel ClC-Ka reveals a conserved interaction interface. Structure. 2007;15:715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meyer S, Dutzler R. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic domain of the chloride channel ClC-0. Structure. 2006;14:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alioth S, Meyer S, Dutzler R, Pervushin K. The cytoplasmic domain of the chloride channel ClC-0: structural and dynamic characterization of flexible regions. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meyer S, Savaresi S, Forster IC, Dutzler R. Nucleotide recognition by the cytoplasmic domain of the human chloride transporter ClC-5. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:60–67. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bennetts B, Rychkov GY, Ng HL, Morton CJ, Stapleton D, et al. Cytoplasmic ATP-sensing domains regulate gating of skeletal muscle ClC-1 chloride channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32452–32458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tseng PY, Bennetts B, Chen TY. Cytoplasmic ATP inhibition of CLC-1 is enhanced by low pH. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:217–221. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zifarelli G, Pusch M. The muscle chloride channel ClC-1 is not directly regulated by intracellular ATP. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:109–116. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bennetts B, Parker MW, Cromer BA. Inhibition of skeletal muscle ClC-1 chloride channels by low intracellular pH and ATP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32780–32791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang XD, Tseng PY, Chen TY. ATP inhibition of CLC-1 is controlled by oxidation and reduction. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:421–428. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Galindo BE, Vacquier VD. Phylogeny of the TMEM16 protein family: some members are overexpressed in cancer. Int.J Mol.Med. 2005;16:919–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, et al. TMEM16A, A Membrane Protein Associated With Calcium-Dependent Chloride Channel Activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression Cloning of TMEM16A as a Calcium-Activated Chloride Channel Subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pifferi S, Dibattista M, Menini A. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stohr H, Heisig JB, Benz PM, Schoberl S, Milenkovic VM, et al. TMEM16B, A Novel Protein with Calcium-Dependent Chloride Channel Activity, Associates with a Presynaptic Protein Complex in Photoreceptor Terminals. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:6809–6818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5546-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kuruma A, Hartzell HC. Bimodal control of a Ca 2+ -activated Cl− channel by different Ca 2+ signals. Journal of General Physiology. 2000;115:59–80. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rock JR, Futtner CR, Harfe BD. The transmembrane protein TMEM16A is required for normal development of the murine trachea. Developmental Biology. 2008;321:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]