Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite an increasing body of evidence on the benefit of lowering elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), there is still considerable concern that patients are not achieving target LDL-C levels.

OBJECTIVE:

The CANadians Achieve Cholesterol Targets Fast with Atorvastatin Stratified Titration (CanACTFAST) trial tested whether an algorithm-based statin dosing approach would enable patients to achieve LDL-C and total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TC/HDL-C) ratio targets quickly.

METHODS:

Subjects requiring statin therapy, but with an LDL-C level of 5.7 mmol/L or lower, and triglycerides of 6.8 mmol/L or lower at screening participated in the 12-week study, which had two open-label, six-week phases: a treatment period during which patients received 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg or 80 mg of atorvastatin based on an algorithm incorporating baseline LDL-C value and cardiovascular risk; and patients who achieved both LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets at six weeks continued on the same atorvastatin dose. Patients who did not achieve both targets received dose uptitration using a single-step titration regimen. The primary efficacy outcome was the proportion of patients achieving target LDL-C levels after 12 weeks.

RESULTS:

Of 2016 subjects screened at 88 Canadian sites, 1258 were assigned to a study drug (1101 were statin-free and 157 were statin-treated at baseline). The proportion of subjects who achieved LDL-C targets after 12 weeks of treatment was 86% (95% CI 84% to 88%) for statin-free patients and 54% (95% CI 46% to 61%) for statin-treated patients. Overall, 1003 subjects (80%; 95% CI 78% to 82%) achieved both lipid targets.

CONCLUSIONS:

Algorithm-based statin dosing enables patients to achieve LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets quickly, with either no titration or a single titration.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Coronary artery disease, Diabetes mellitus, Dyslipidemias, Hypercholesterolemia, Statin

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Malgré un ensemble de preuves croissant sur les bienfaits d’abaisser les taux élevés de cholestérol à lipoprotéines de basse densité (C-LDL), on s’inquiète encore beaucoup du fait que les patients n’atteignent pas les taux de C-LDL ciblés.

OBJECTIF :

L’étude CanACTFAST sur l’atteinte des cibles de cholestérol par les Canadiens au moyen du titrage stratifié d’atorvastatine était conçue pour évaluer si une posologie de statines calculée à l’aide d’un algorithme permettrait aux patients d’atteindre rapidement les cibles de C-LDL et de ratio entre le cholestérol total et le cholestérol à lipoprotéines de haute densité (CT/C-HDL).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les sujets qui avaient besoin d’une thérapie aux statines, mais dont le taux de C-LDL était de 5,7 mmol/L ou moins et le taux de triglycérides, de 6,8 mmol/L ou moins au moment du dépistage, ont participé à l’étude de 12 semaines, pourvue de deux phases ouvertes de six semaines : une période de traitement pendant laquelle les patients recevaient 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg ou 80 mg d’atorvastatine selon un algorithme intégrant la valeur de C-LDL de départ et le risque cardiovasculaire; les patients qui avaient atteint les cibles de C-LDL et de ratio CT/C-HDL au bout de six semaines maintenaient la même dose d’atorvastatine. Les patients qui n’atteignaient pas les deux cibles ont reçu un surtitrage de la dose au moyen d’une posologie par simple titrage. La proportion de patients atteignant les taux de C-LDL au bout de 12 semaines était l’issue d’efficacité primaire.

RÉSULTATS :

Des 2 016 sujets ayant fait l’objet d’un dépistage dans 88 centres canadiens, 1 258 ont reçu à un médicament à l’étude (1 101 ne prenaient pas de statines et 157 recevaient un traitement aux statines dès le départ). Ainsi, 86 % des sujets ne prenant pas de statines ont atteint les cibles de C-LDL au bout de 12 semaines de traitement (95 % IC 84 % à 88 %) par rapport à 54 % de ceux en recevant (95 % IC 46% à 61 %). Dans l’ensemble, 1 003 sujets (80 %; 95 % IC 78 % à 82 %) ont atteint les deux cibles lipidiques.

CONCLUSIONS :

Une posologie de statines calculée au moyen d’un algorithme permet aux patients d’atteindre rapidement les cibles de C-LDL et de ratio CT/C-HDL, sans titrage ou au moyen d’un seul titrage.

Clinical trials have shown that the use of statins to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels can reduce the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) morbidity and mortality (1–3).

Canadian recommendations for the treatment of dyslipidemia are based on risk, largely determined using Framingham equations (4). Aggressive lipid lowering is recommended in patients with CAD or CAD equivalents (eg, diabetes, chronic kidney disease), and asymptomatic individuals with a 10-year CAD risk of 20% or greater. Individuals at moderate (10% to 19% risk over 10 years) or low risk (10% or lower risk over 10 years) are assigned to incrementally less aggressive targets.

Current management of dyslipidemia is suboptimal (5–8). Consequently, many very high-risk patients do not achieve and maintain recommended lipid targets (5,9). In the Canadian Lipid Study – Observational (CALIPSO) study (10) of 3721 statin-treated patients, 27.2% of all patients and 36.4% of those at high risk for CAD did not achieve LDL-C targets.

Achieving LDL-C targets can be a long and difficult process. Several dose titrations, typically months apart, are often required and some patients still do not reach the target. Recommendations for managing high-risk patients now include prompt intervention with diet and medication using an initial drug and dose calculated to achieve the necessary reduction in LDL-C (11). A treatment strategy that helps patients quickly achieve their LDL-C target will therefore not only have a positive clinical impact, as illustrated by recent studies comparing aggressive atorvastatin treatment with usual care (12,13), it may also increase adherence to treatment.

The CANadians Achieve Cholesterol Targets Fast with Atorvastatin Stratified Titration (CanACTFAST) trial was designed to test whether a calculated atorvastatin treatment approach using a starting dose appropriate for the level of LDL-C reduction required by the patient’s cardiovascular (CV) risk category and with either no titration or a single titration step would enable patients to achieve their designated LDL-C and total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TC/HDL-C) ratio targets quickly. The recently published international Achieve Cholesterol Targets Fast with Atorvastatin Stratified Titration (ACTFAST) study (14) demonstrated the effectiveness of such a strategy, but included only patients at high risk for a CV event. In contrast, the CanACTFAST trial studied a wide range of CV risk to determine whether the strategy was effective over the range of coronary atherosclerotic risk profiles, and used a graded treatment approach.

METHODS

CanACTFAST was a multicentre (88 family physician and specialist sites across Canada), open-label prospective study. The 12-week, single-step titration trial was designed to assess the percentage of dyslipidemic patients who could achieve LDL-C targets (based on the 2003 Canadian recommendations [15] [Table 1] that were in effect at the time) with initial atorvastatin doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg or 80 mg.

TABLE 1.

Risk categories and target lipid levels

| Risk category | 10-year risk estimate of CAD | LDL-C target, mmol/L | TC/HDL-C ratio target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High* | ≥20% (includes those with diabetes or any atherosclerotic disease) | <2.5 | and | <4.0 |

| Moderate | 11%–19% | <3.5 | and | <5.0 |

| Low | ≤10% | <4.5 | <6.0 |

Targets are based on the 2003 national guidelines (15), which were the guidelines available at the time the study was conducted.

Study medication should be started immediately concomitant with diet and therapeutic lifestyle changes. CAD Coronary artery disease; LDL-C Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC/HDL-C Total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Patient population

Eligible subjects were 30 to 79 years of age, with elevated LDL-C despite having adhered to an appropriate diet before entry into the study (except for high-risk patients in whom treatment could have been started concomitantly [15]). In addition, subjects had to be eligible for LDL-C-lowering drug therapy at baseline, as determined by the LDL-C cut-off points defined in Canadian recommendations (15) (Table 1), and be willing to follow the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) II diet at baseline and throughout the trial (16). Because high LDL-C warrants aggressive therapy and treatment strategies that do not permit a standard trial, and statins are not the initial drug of choice for high triglyceride (TG), subjects were included only if their LDL-C level was 5.7 mmol/L or lower, and their TG level was 6.8 mmol/L or lower at the screening examination.

The following patients were excluded from participation:

Subjects already at LDL-C targets acheived by taking statins other than atorvastatin;

Subjects receiving statin doses higher than the following: 10 mg to 40 mg simvastatin; 20 mg to 40 mg fluvastatin, pravastatin or lovastatin; and 10 mg to 20 mg rosuvastatin;

Subjects taking any other lipid-lowering medication (eg, bile acid sequestrant, fibrate, nicotinic acid, fish oil), CYP 3A4 inhibitor (including macrolide antibiotics) or oral corticosteroid; and

Subjects with impaired hepatic function, creatine phosphokinase more than three times the upper limit of normal at screening, uncontrolled diabetes (defined as hemoglobin A1c of greater than 10% at screening) and uncontrolled hypertension.

Intervention

Following screening according to 2003 Canadian recommendations (16), eligible patients were treated as follows:

Phase 1: Open-label treatment for six weeks with 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg or 80 mg atorvastatin based on an algorithm incorporating baseline LDL-C value and previous statin use. Subjects who were statin free at screening were assigned a starting dose according to Table 2. Subjects who were taking usual maintenance doses of a statin at screening (statin-treated) were assigned a starting dose according to Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Initial atorvastatin dose assignment for statin-free subjects

| Baseline LDL-C, mmol/L |

Risk category (10-year CAD risk) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤10%) | Moderate (11%–19%) | High (≥20%) | |

| 2.50–3.60 | NA | 10 mg (if LDL-C ≥3.5 mmol/L) | 10 mg |

| 3.61–3.86 | NA | 10 mg | 20 mg |

| 3.87–4.12 | NA | 10 mg | 40 mg |

| 4.13–4.38 | NA | 10 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.39–4.63 | 10 mg (if LDL-C ≥4.5 mmol/L) | 10 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.64–4.89 | 10 mg | 20 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.9–5.7 | 10 mg | 40 mg | 80 mg |

CAD Coronary artery disease; LDL-C Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA Not applicable

TABLE 3.

Initial atorvastatin dose assignment for subjects treated with a statin at baseline

| Baseline LDL-C, mmol/L |

Risk category (10-year CAD risk) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤10%) | Moderate (11%–19%) | High (≥20%) | |

| 2.50–3.60 | NA | 20 mg (if LDL-C ≥3.5 mmol/L) | 20 mg |

| 3.61–3.86 | NA | 20 mg | 40 mg |

| 3.87–4.12 | NA | 20 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.13–4.38 | NA | 20 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.39–4.63 | 20 mg (if LDL-C ≥4.5 mmol/L) | 20 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.64–4.89 | 20 mg | 40 mg | 80 mg |

| 4.90–5.70 | 20 mg | 40 mg | 80 mg |

CAD Coronary artery disease; LDL-C Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA Not applicable

Phase 2: Patients who achieved both lipid targets at six weeks continued on the same open-label dose of atorvastatin for an additional six weeks. Subjects who had not reached both LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets after six weeks of treatment were uptitrated to the next open-label dose of atorvastatin according to a single-step titration regimen (Tables 2 and 3).

Efficacy parameters

The primary efficacy outcome measure was the proportion of patients achieving their designated target LDL-C after 12 weeks of treatment using the starting doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg or 80 mg atorvastatin according to their 10-year CAD risk category. The thresholds to treat and targets were defined based on 2003 Canadian recommendations (15) (Table 1). Secondary efficacy variables included the global proportion of patients reaching targets when risk categories were combined, the proportion of subjects achieving both their LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets after six and 12 weeks of treatment, and the proportions of subjects achieving either LDL-C or TC/HDL-C ratio targets after six and 12 weeks of treatment. Additional a priori secondary outcomes included the proportion of subjects who achieved the LDL-C target based on the specific statin dose at baseline, as well as age, sex, diabetes status and metabolic syndrome status (given the link between metabolic syndrome and CAD risk), and using the NCEP Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III definition [17]).

Safety variables included treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) and severe adverse events (SAEs).

Direct measurement of LDL-C was performed by a central laboratory using a homogeneous enzymatic calorimetric assay (reliable with TG plasma values up to 13.5 mmol/L) (Roche LDL-C Plus 2nd Generation, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was undertaken on an intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol basis. The ITT population, the primary population for assessment of efficacy, consisted of patients who were assigned a starting dose of active study drug, had a valid baseline assessment, took at least one dose of study medication, and had at least one subsequent assessment.

RESULTS

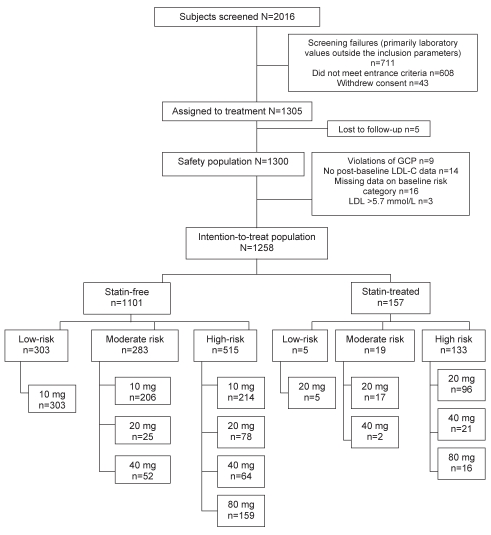

Between January 2004 and May 2006, 2016 subjects were screened at 88 Canadian sites. Of the 1258 subjects in the ITT population, 1101 were statin free and 157 were statin treated at baseline. The disposition of patients is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1).

Patient disposition. GCP Good clinical practices; LDL-C Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Baseline demographics and mean baseline laboratory values are shown in Table 4. CAD, CVD and diabetes were more prevalent in the statin-treated group. At baseline, 24% of patients in the overall study population were classified as low risk, 24% as moderate risk and 52% as high risk. Among the statin-treated patients, 85% were high risk at baseline.

TABLE 4.

Baseline characteristics – intention-to-treat population

| Statin free (n=1101) | Statin treated (n=157) | All (N=1258) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 687 (62.4) | 99 (63.1) | 786 (62.5) |

| Age, years | 58.0±10.51 | 60.9±9.55 | 58.4±10.43 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 990 (89.9) | 144 (91.7) | 1134 (90.1) |

| Black | 21 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 25 (2) |

| Asian | 78 (7.1) | 8 (5.1) | 86 (6.8) |

| Other | 12 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 13 (1.0) |

| Weight, kg | 83.0±16.44 | 83.2±19.35 | 83.0±16.82 |

| Waist circumference, cm | |||

| Men | 101.1±1.7 | 103.0 ±1 5.7 | 101.3±12.2 |

| Women | 95.0±13.4 | 96.7±12.9 | 95.2±13.3 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 272 (24.7) | 31 (19.7) | 303 (24.1) |

| TC, mmol/L | 6.4±0.9 | 5.6±0.9 | 6.3±1.0 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 4.3±0.8 | 3.4±0.7 | 4.2±0.8 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.3±0.3 | 1.3±0.3 | 1.3±0.3 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 5.2±1.2 | 4.6±1.4 | 5.1±1.2 |

| TG, mmol/L | 2.2±1.0 | 2.3±1.1 | 2.2±1.0 |

| ApoB, mmol/L | 1.3±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.3±0.2 |

| SBP, mmHg | 131.0±14.0 | 131.5±13.7 | 131.1±14.0 |

| DBP, mmHg | 79.3±8.1 | 78.5±8.1 | 79.2±8.1 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.9±0.9 | 6.2±0.9 | 6.0±0.9 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.9±1.6 | 6.3±1.5 | 6.0±1.6 |

| CAD, n (%) | 71 (6.4) | 72 (45.9) | 143 (11.4) |

| CVD, n (%) | 35 (3.2) | 13 (8.3) | 48 (3.8) |

| PVD, n (%) | 21 (1.9) | 7 (4.5) | 28 (2.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 578 (52.5) | 108 (68.8) | 686 (54.5) |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 275 (25) | 67 (42.7) | 342 (27.2) |

| Treated with insulin | 20 (7.3) | 3 (4.5) | 23 (6.7) |

| Treated with oral antihyperglycemic agents | 188 (68.4) | 37 (55.2) | 225 (65.8) |

| Treated with diet | 118 (42.9) | 36 (53.7) | 154 (45.0) |

| Not treated | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (0.9) |

| 10-year CAD risk ≥20% | 145 (13.2) | 7 (4.5) | 152 (12.1) |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. ApoB Apolipo-protein B; CAD Coronary artery disease; CVD Cardiovascular disease; DBP Diastolic blood pressure; FPG Fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c Hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PVD Peripheral vascular disease; SBP Systolic blood pressure; TC Total cholesterol; TG Triglyceride

Primary outcome

Of the 1258 patients in the ITT population, 1180 (93.8%) completed the study and 1062 (84.4%) were considered to have been compliant with their regimen.

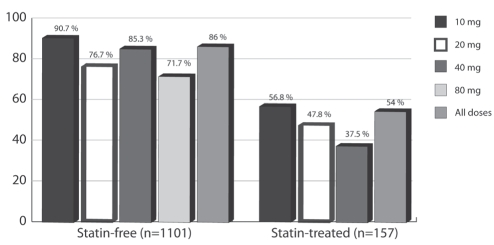

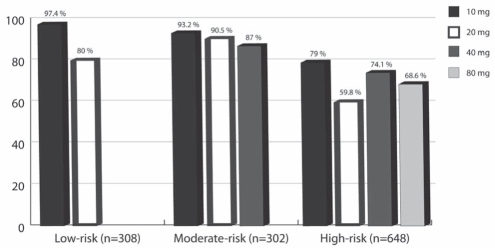

Table 5 shows the proportions of patients achieving LDL-C targets at six and 12 weeks. Using last observation carried forward analysis (LOCF), week 12 LOCF is also presented. Overall, there were 1248 observed cases at the primary end point; only 10 values (fewer than 0.5% of the ITT population) were carried forward to the LOCF analysis; hence, the results between the observed cases and the LOCF analysis were almost identical. The overall proportion of subjects achieving LDL-C targets after 12 weeks of treatment was 82%. Figure 2 shows the proportion of statin-free and statin-treated patients achieving the LDL-C target by each initial dose. Overall, 86% (95% CI 84% to 88%) of statin-free patients and 54% (95% CI 46% to 61%) of statin-treated patients reached their targets. Figure 3 shows these proportions divided into low-, medium- and high-risk groups. In the per protocol population, the proportions of subjects achieving targets were slightly and systematically higher than in the ITT population in each case (overall 4% higher and up to 9% higher in the 80 mg group).

TABLE 5.

Proportion of subjects reaching low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target by initial dose allocation and study week (intention-to-treat population)

| Initial atorvastatin dose allocation |

Week 6 (n=1206) |

Week 12 (n=1248) |

LOCF (n=1258) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Proportion, % (95% CI) | n | Proportion, % (95% CI) | n | Proportion, % (95% CI) | |

| 10 mg | 698 | 93.1 (91.3–95.0) | 715 | 90.6 (88.5–92.8) | 723 | 90.7 (88.6–92.9) |

| 20 mg | 213 | 71.4 (65.3–77.4) | 220 | 66.4 (60.1–72.6) | 221 | 66.1 (59.8–72.3) |

| 40 mg | 137 | 79.6 (72.8–86.3) | 139 | 79.1 (72.4–85.9) | 139 | 79.1 (72.4–85.9) |

| 80 mg | 158 | 82.3 (76.3–88.2) | 174 | 68.4 (61.5–75.3) | 175 | 68.6 (61.7–75.5) |

| All doses | 1206 | 86.3 (84.4–88.3) | 1248 | 82.0 (79.8–84.1) | 1258 | 82.0 (79.9–84.2) |

LOCF Last observation carried forward analysis

Figure 2).

Proportion of subjects achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target, by starting atorvastatin dose in the statin-treated and statin-free groups (intention-to-treat, last observation carried forward analysis)

Figure 3).

Proportion of subjects achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target, by risk category and starting atorvastatin dose (intention-to-treat, last observation carried forward analysis)

Secondary outcomes

Among subjects with diabetes (n=354), 80% (95% CI 75% to 84%; 228 of 286) of statin-free patients and 53% (95% CI 41% to 65%; 36 of 68) of statin-treated patients reached the primary end point. Of 474 patients with the metabolic syndrome, 83% (95% CI 79% to 86%; 334 of 404) of statin-free patients and 53% (95% CI 41% to 65%; 37 of 70) of statin-treated patients achieved the primary end point.

Patients who did not achieve both LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets at six weeks required uptitration: 11.2% in the 10 mg group, 37.1% in the 20 mg group and 26.3% in the 40 mg group. Overall, 79.7% (95% CI 78% to 82%; 1003 of 1258) of subjects achieved both of their LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets.

Safety

Safety results are summarized in Table 6. Overall, the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 11.7% (4.1% of subjects withdrew from the study due to treatment-related AEs). There were no cases of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis. The overall incidence of treatment-related SAEs was 0.08%. Subjects in the 80 mg group had the highest incidence of all-cause AEs (50.5%), withdrawal from the study due to all-cause AEs (9.3%), myalgia (6.0%), treatment-related AEs (18.7%) and withdrawal from the study due to treatment-related AEs (9.3%).

TABLE 6.

Overview of safety

| All cause |

Treatment dose |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg (n=743) | 20 mg (n=230) | 40 mg (n=145) | 80 mg (n=182) | All (N=1300) | |

| Subjects with: | |||||

| AEs | 41.9 | 45.2 | 48.3 | 50.5 | 44.4 |

| SAEs | 0.7 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Subjects who withdrew from study due to: | |||||

| AEs | 3.8 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 9.3 | 4.4 |

| Lab abnormalities | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Musculoskeletal AEs | 9.4 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.2 |

| Myalgia | 3.9 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 4.4 |

| Myopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Treatment related | |||||

| Subjects with: | |||||

| AEs | 9.8 | 13.0 | 10.3 | 18.7 | 11.7 |

| SAEs | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

| Subjects who withdrew from study due to: | |||||

| AEs | 3.4 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 9.3 | 4.1 |

| Lab abnormalities | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Musculoskeletal AEs | 2.8 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.3 |

| Myalgia | 2.0 | 2.6 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 2.7 |

| Myopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data presented as the percentage of patients. AE Adverse events; Lab Laboratory; SAE Severe adverse events

DISCUSSION

LDL-C lowering is an essential component of CV risk reduction, and strategies that help patients quickly achieve their LDL-C target have been shown to have a positive impact on the reduction of CV events (1–3). A traditional approach of progressive uptitration of statin doses may result in suboptimal proportions of patients achieving lipid targets (5–9) and may contribute to patient nonadherence, and patient and physician frustration.

The ACTFAST study (14), which was conducted using only subjects at high risk of CV events, showed that by initiating therapy at doses selected according to baseline LDL-C levels, 72% of all subjects (79.6% of statin-free and 58.7% of statin-treated subjects) achieved a target LDL-C of lower than 2.6 mmol/L after 12 weeks. The CanACTFAST study used Canadian recommendations, which categorize risk based on the Framingham risk equations, and showed that a treatment strategy integrating CV risk and different starting dosages can be used to tailor a successful drug treatment approach that is appropriate across risk categories. Extending the range of patients who can benefit from such an approach is important because patients at low or moderate risk of CV events in the short term may be at high long-term risk due to the cumulative effects of a single risk factor and/or changes in risk factors over time (4).

Consistent with other reports, the CanACTFAST approach of ensuring appropriate starting doses and timely dose adjustments increased the proportions of patients who attained lipid targets (11,18,19). However, patients do not always undergo a dose titration approach. Foley et al (20) reported that of high-risk subjects who failed to reach their therapeutic target with a starting dose of statin, only 45% had dose uptitration. Yan et al (7) reported that only 9.9% of high-risk patients who failed to meet their target LDL-C level of lower than 2.6 mmol/L were taking a high-dose statin.

Subjects at highest risk (ie, those with CAD or CAD equivalent) have the lowest LDL-C target and may therefore often require higher doses to achieve larger LDL-C reductions. Seventy-two per cent of the CanACTFAST group that received the highest dose of atorvastatin (80 mg per day) and were previously statin free, achieved their target LDL-C. While lower than the overall group (and consistent with findings that higher-risk individuals have more difficulty achieving target values), almost three-quarters of these high-risk patients attained their targets in 12 weeks with the titration protocol. Our data extend the findings of other investigators. Brown et al (21) reported that 32% of higher-risk subjects achieved a designated LDL-C target of lower than 2.6 mmol/L after 12 weeks of 10 mg atorvastatin therapy. When the dose was titrated up to 80 mg, 83% were able to achieve this target (21). In the New Atorvastatin Starting Doses: A Comparison (NASDAC) trial (22), more subjects with CAD or CAD equivalents reached their targets with higher initial doses (80.9% with a 40 mg dose and 80.3% with an 80 mg dose) than with lower initial doses (46.5% with a 10 mg dose and 66.2% with a 20 mg dose). The CanACTFAST protocol enabled 80% of subjects to achieve not only their LDL-C target, but their target TC/HDL-C ratio as well.

Safety

With the caveat that there was no placebo group against which to compare AEs, the safety findings of the present study were comparable with those of other atorvastatin trials. Approximately 50% of those in the 80 mg group and 41.9% of subjects in the 10 mg group experienced an AE. In a retrospective analysis of pooled safety data from 49 atorvastatin trials (23), these rates were 47.6% in the 80 mg group and 53.3% of subjects in the 10 mg group. In ACTFAST, the rates were 44.9% in the 80 mg group and 37.4% in the 10 mg group. The rate of treatment-related AEs in the present study was 18.7% in the 80 mg treatment group and 9.8% in the 10 mg group, which is consistent with treatment-related AE rates of 14.6% and 13.5% found in the retrospective analysis (23), and 19.4% and 10.7% found in the ACTFAST trial (14). In the Treating to New Targets (TNT) trial (24), AEs related to treatment occurred in 8.1% of the 80 mg group versus 5.8% of the 10 mg group. In the present study, treatment-related myalgia was reported in 3.8% of the 80 mg group and 2.0% of the 10 mg group, compared with 1.5% and 1.4%, respectively, in the retrospective pooled analysis (23), and 4.7% and 4.8%, respectively, in the TNT study (24). In terms of withdrawals due to treatment-related AEs, the rates in the present study were 9.3% in the 80 mg group and 3.4% in the 10 mg group, which were higher than those detected in the retrospective analysis mentioned above (1.8% and 2.4%, respectively) and those detected in the ACTFAST study (5.1% and 2.7%, respectively) (14), but were comparable with the rate in the TNT trial (7.2% and 5.3%, respectively) (24). Some of the differences in rates seen in the present study may be reflective of the fact that patients came from a primary care setting, the study had an open-label design and there was no run-in phase, unlike some previous studies. The results of the present study further reinforce the safety of the 80 mg atorvastatin dose.

Limitations

The real-life setting of the present trial provides useful clinical information, but the limitations of an uncontrolled, nonrandomized design must be recognized, including potential biases in selection and in regression to the mean (due to the lack of randomization). In addition, because only short-term end points were studied, the long-term rates of AEs and compliance with the drug compared with standard uptitration (25), need to be defined.

The present study was not a placebo-controlled trial designed to evaluate drug efficacy. Rather, the trial was designed to examine the efficacy of a treatment schedule-based assignment of drug dosage according to patient risk rather than the traditional approach of starting at a low dose and gradually titrating the dosage upwards. Finally, it is unknown how the findings from the present trial compare with what would be expected with a traditional treatment approach. However, our study demonstrates high efficacy with a specific treatment algorithm, allowing for subsequent research to compare this approach with traditional therapy in a randomized trial.

CONCLUSIONS

An algorithm-based strategy of initiating therapy using a statin dosage that takes into account the patient’s baseline LDL-C and CAD risk enables a patient to achieve his or her designated LDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratio targets quickly, with either no titration or just a single titration step. Such an approach may offer clinicians a simple and practical method to reduce key CV risk factors across a wide range of risk profiles.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study investigators (listed in Appendix A), Dr Karima Fazal-Karim (Clinical Scientist) and Joseph Zoccoli (Study Manager) from Pfizer Canada Inc, for their invaluable contributions to this study, as well Cynthia N Lank, Halifax, Nova Scotia, for her editorial assistance.

APPENDIX A. STUDY INVESTIGATORS:

Dr Geeta Achyuthan, Regina, Saskatchewan; Dr Naresh Aggarwal, Brampton, Ontario; Dr Ronald Akhras, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Roy C Allison, Thunder Bay, Ontario; Dr Isabel Alvarez, Markham, Ontario; Dr Donald M Andrew, Rothesay, New Brunswick; Dr Robert A Baker, Richmond, British Columbia; Dr Kenneth E Bayly, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Dr Joseph Berlingieri, Burlington, Ontario; Dr Bruno Bernucci, St Leonard, Quebec; Dr Graeme Bethune, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Dr Patrick Bisson, Greenfield Park, Quebec; Dr Raynald Boily, St Catharines, Ontario; Dr Jean Yves Boutet, Amos, Quebec; Dr Jeannot Breton, Plessisville, Quebec; Dr Brent E Bukovy, Thunder Bay, Ontario; Dr Peter Cameron, Midland, Ontario; Dr Brian Carlson, Coquitlam, British Columbia; Dr Ashok K Chadha, Napanee, Ontario; Dr Raja Chehayeb, Greenfield Park, Quebec; Dr Roy Chernoff, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Dr Raphael Cheung, Windsor, Ontario; Dr Tak-yee Cheung, Harrow, Ontario; Dr Walter Chow, Victoria, British Columbia; Dr John M Collingwood, St John’s, Newfoundland; Dr Howard S Conter, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Dr Ian Cowan, North Bay, Ontario; Dr Donald Craig, Saint John, New Brunswick; Dr David Crawford, Winnipeg, Manitoba; Dr Thomas Crawford, Glace Bay, Nova Scotia; Dr Michael Csanadi, Fort Erie, Ontario; Dr I Dan Dattani, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Dr Pierre Dauth, Cowansville, Quebec; Dr Ripple Dhillon, Oshawa, Ontario; Dr Giuseppe D’Ignazio, Hawkesbury, Ontario; Dr Vincent Dininno, Medicine Hat, Alberta; Dr Richard Dumas, Laval, Quebec; Dr Connie L Ellis, Calgary, Alberta; Dr Claude Gagne, Ste-Foy, Quebec; Dr Rene Gagnon, Quebec, Quebec; Dr Daniel Gaudet, Chicoutimi, Quebec; Dr Roland Genge, Baddeck, Nova Scotia; Dr Sally J Godsell, Kelowna, British Columbia; Dr Bernard Green, Toronto, Ontario; Dr Roy Gritter, Edmonton, Alberta; Dr Steven Grover, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Jeff Habert, Thornhill, Ontario; Dr Rafik Habib, Laval, Quebec; Dr William Hall, Calgary, Alberta; Dr Brian J Hartford, Thunder Bay, Ontario; Dr Robert A Hegele, London, Ontario; Dr Sam Henein, Newmarket, Ontario; Dr Evan Howlett, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Dr David H James, Courtice, Ontario; Dr Subodh D Kanani, Toronto, Ontario; Dr Martin Kates, Etobicoke, Ontario; Dr Allan J Kelly, Edmonton, Alberta; Dr Michael Kennedy, Richmond Hill, Ontario; Dr Sy Lam, Calgary, Alberta; Dr Daniel A Landry, Moncton, New Brunswick; Dr Claude Laroche, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Benjamin Howard Lasko, Toronto, Ontario; Dr Christian Leduc, Vaudreuil, Quebec; Dr Lawrence A Leiter, Toronto, Ontario; Dr Wilson Leung, Niagara Falls, Ontario; Dr Noah Levine, Toronto, Ontario; Dr Gary Lewis, Toronto, Ontario; Dr John Li, Moncton, New Brunswick; Dr Pierre Liboiron, Laval, Quebec; Dr Graham Loeb, Lindsay, Ontario; Dr Benoit Loranger, Saint-Eustache, Quebec; Dr Kevin Luces, Oshawa, Ontario; Dr Patrick Tung Ma, Calgary, Alberta; Dr John Macfadyen, Orillia, Ontario; Dr Terrence Magennis, Montague, Prince Edward Island; Dr David Marr, Saint John, New Brunswick; Dr Giuseppe Mazza, St Leonard, Quebec; Dr Michel Meunier, Sainte Julie, Quebec; Dr Ken Mitton, Moncton, New Brunswick; Dr David Mymin, Winnipeg, Manitoba; Dr Rick Nuels, Edmonton, Alberta; Dr Michael FJ O’Mahony, Sarnia, Ontario; Dr Frank P Onuska, Kitchener, Ontario; Dr Jean-Pascal Ouellet, Sherbrooke, Quebec; Dr François Pigeon, Le Gardeur, Quebec; Dr Simon W Rabkin, Vancouver, British Columbia; Dr Anthony Rolfe, St John’s, Newfoundland; Dr Kevin K Saunders, Winnipeg, Manitoba; Dr Nawal Kishore Sharma, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Dr Mark Sherman, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Daniel S Shu, Coquitlam, British Columbia; Dr Parmjit Sohal, Surrey, British Columbia; Dr Rizwan Somani, Langley, British Columbia; Dr Jack Sussman, Downsview, Ontario; Dr John P Taliano, St Catharines, Ontario; Dr Kim-Weng W Tan, Ottawa, Ontario; Dr Alain Tardif, Quebec, Quebec; Dr Ivor Teitelbaum, North York, Ontario; Dr Morris E Trager, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Dr Chantal Turcotte, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Douglas KH Tweel, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; Dr Richard Tytus, Hamilton, Ontario; Dr Ehud Ur, Vancouver, British Columbia; Dr Kandiah Vaithianathan, Scarborough, Ontario; Dr Pierre Varvarikos, Montreal, Quebec; Dr Azim M Velji, Niagara Falls, Ontario; Dr Richard A Ward, Calgary, Alberta; Dr Jean-Pierre Yelle, Salaberry du Valleyfield, Quebec; Dr David Yip, Edmonton, Alberta; and Dr George Zimakas, Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Footnotes

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: NCT00150371. Accessible at <http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00150371?order=1>.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT: This study was funded by Pfizer Canada Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: The steering committee (EU, AL, SWR, CC and LAL) designed the trial in collaboration with Pfizer Canada Inc. EU and LAL identified the initial primary and secondary end points, which were then modified and approved by the steering committee. Data coordination, analysis and synthesis were performed by Pfizer Canada Inc, and the subject allocation and data analysis were verified by an independent statistician. Each author listed above contributed substantially to the conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the attached version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENTS: EU has received research funding from, has provided continuing medical education (CME) on behalf of, and has acted as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, Merck Frosst/Schering-Plough, and Pfizer. AL has received grant and CME support from AstraZeneca, Biovail, Merck Frosst/Schering Plough, Novartis, Pfizer, sanofi-aventis, and Servier. SWR has provided CME on behalf of, and/or has acted as a consultant to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck and Pfizer. CC is employed as Medical Advisor, Medical Affairs, Therapeutic Area (Cardiovascular and Metabolic), Medical Division, Pfizer Canada Inc. LAL has received research funding from, has provided CME on behalf of, and has acted as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, Merck Frosst/Schering-Plough, and Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baignet C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. for the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) Collaboration Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomized trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson R, Frohlich J, Fodor G, for the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:913–27. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fodor JG, McPherson R, Dafoe WA, Grenville A. Investigation and treatment of hypercholesterolemia and other dyslipidemias in Canadian primary care practice. CVD Prevention. 1998;1:225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hackam DG, Tan MK, Honos GN, Letier LA, Langer A, Goodman SG, for the Vascular Protection Registry Investigators How does the prognosis of diabetes compare with that of established vascular disease? Insights from the Canadian Vascular Protection (VP) Registry. Am Heart J. 2004;148:1028–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M, et al. for the Vascular Protection (VP) and Guidelines Oriented Approach to Lipid Lowering (GOALL) Registries Investigators Contemporary management of dyslipidemia in high-risk patients: Targets still not met. Am J Med. 2006;119:676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin PC, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Alter DA, Tu JV. Missed opportunities in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction: An assessment of the effects of statin underprescribing on mortality. Am Heart J. 2006;151:969–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fodor JG, Frohlich JJ, Genest JJ, Jr, McPherson PR. Recommendations for the management and treatment of dyslipidemia. Report on the Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias. CMAJ. 2000;162:1441–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgault C, Davignon J, Fodor G, et al. Statin therapy in Canadian patients with hypercholesterolemia: The Canadian Lipid Study – Observational (CALIPSO) Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:1187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson R, Angus C, Murray P, Genest J. Efficacy of atorvastatin in achieving National Cholesterol Education Program low-density lipoprotein targets in women with severe dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The Women’s Atorvastatin Trial on Cholesterol (WATCH) Am Heart J. 2001;152:489–96. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deedwania P, Stone PH, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Effects of intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy on myocardial ischemia in older patients with coronary heart disease: Results of the Study Assessing Goals in the Elderly (SAGE) Circulation. 2007;115:700–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1071–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martineau P, Gaw A, de Teresa E, et al. Effect of individualizing starting doses of a statin according to baseline LDL-cholesterol levels on achieving cholesterol targets: The Achieve Cholesterol Targets Fast with Atorvastatin Stratified Titration (ACTFAST) study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:135–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genest J, Frohlich J, Fodor G, McPherson R. Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease: Summary of the 2003 update. CMAJ. 2003;169:921–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguilar-Salinas C, Gomez-Perez F, Posadas-Romero C, et al. Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in hyperlipidemic, type 2 diabetic patients. A 34-week, multicenter, open-label study. Atherosclerosis. 2000;152:489–96. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrew T, Ballantyne See, Hsia J, Kramer J. Achieving and maintaining National Education Program low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals with five statins. Am J Med. 2001;111:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Jr, Crouse JR, III, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown A, Bakker-Arkema R, Yellen L, et al. Treating patients with documented atherosclerosis to National Cholesterol Education Program-recommended low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol goals with atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:665–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones PH, McKenney JM, Kardis DG, Downey J. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of atorvastatin initiated at different starting doses in patients with dyslipidemia. Am Heart J. 2005;9:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman C, Tsai J, Szarek M, Luo D, Gibson E. Comparative safety of atorvastatin 80 mg versus 10 mg derived from analysis of 49 completed trials in 14,326 patients. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. for the Treating to New Targets (TNT) Investigators Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. New Engl J Med. 2005;352:1425–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence to statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2000;288:462–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]