Abstract

The CardioWest™ temporary total artificial heart serves as a viable bridge to orthotopic heart transplantation in patients who are experiencing end-stage refractory biventricular heart failure. This device is associated with a low, albeit still substantial, risk of thrombosis. Platelet interactions with artificial surfaces are complex and result in continuous activation of contact proteins despite therapeutic anticoagulation. We searched the medical literature (publication dates, January 1962–October 2009) in order to evaluate means of mitigating adverse events that have occurred after implantation of the CardioWest temporary total artificial heart.

We conclude that the use of a multitargeted antithrombotic approach, involving anticoagulation (bivalirudin and warfarin) and antiplatelet therapy (dipyridamole and aspirin), can mitigate the procoagulative effects of mechanical circulatory assist devices, particularly those that are associated with the CardioWest temporary total artificial heart. Careful monitoring with use of a variant multisystem approach, involving efficacy tests (thrombelastography and light transmittance aggregometry), safety tests (laboratory analyses), and warfarin genomics, may maximize the therapeutic actions and minimize the bleeding risks that are associated with the multitargeted antithrombotic approach. The development and monitoring of individualized antithrombotic regimens require that informed health professionals appreciate the complexities and grasp the hazards that are associated with these therapies.

Key words: Anticoagulants/administration & dosage/pharmacokinetics/therapeutic use; antithrombins/administration & dosage/therapeutic use; combined modality therapy; complement activation; equipment design; fibrinolytic agents/therapeutic use; heart failure/therapy; heart-assist devices/adverse effects; heart, artificial/adverse effects/trends; platelet aggregation; thrombelastography; thromboembolism/etiology/prevention & control

Approximately 5 million people in the United States have the heart-failure syndrome, and an additional half-million cases are diagnosed annually.1 End-stage refractory heart failure is the most life-threatening manifestation of the heart-failure syndrome. Options available to patients with this condition include palliation, placement of a ventricular assist device, or orthotopic heart transplantation (OHT). Unfortunately, OHT is available only to approximately 2,500 patients annually, due to a shortage of donor hearts. As a result, approximately 60,000 people die while awaiting heart transplantation.1,2

Implantation of the CardioWest™ (SynCardia Systems, Inc.; Tucson, Ariz) temporary total artificial heart (TAH-t) has proved to be viable as a bridge to transplantation in OHT candidates who have end-stage refractory biventricular heart failure and who are at risk of imminent death. In order to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the CardioWest TAH-t, Copeland and colleagues conducted a prospective, multicenter, controlled phase-III trial under investigational device exemption.3 Eligible patients included 130 OHT candidates with New York Heart Association functional class IV heart failure, body surface areas of 1.7 to 2.5 m2, cardiac indices of ≤2 L/min/m2, vasoactive or inotropic drug use, or intra-aortic counterpulsation use. Indices of end-organ perfusion (such as hemodynamic values, urine output, and laboratory values) improved immediately after TAH-t implantation. In comparison with the control group, patients in the CardioWest TAH-t group had a higher survival rate to transplantation (79% vs 46%, P <0.001), a significantly longer mean time from study entry to death or transplantation (71.9 vs 8.5 d, P <0.001), and a significantly greater 1-year survival rate (70% vs 31%, P <0.001). The TAH-t was very reliable over more than 12,000 patient-days of use, failing only once (at day 124 after implantation) and malfunctioning only 19 times. Of the major adverse events that occurred during the 9-year study period, 35 were neurologic (6 fatal), 18 were thromboembolic (3 fatal), and 5 were hemolytic (none fatal).3 The fatal events were not related to the pump, but arose from surgery or antithrombotic therapy (infection, 19%; renal dysfunction, 17%; and bleeding, 16%).

We performed a search of the medical literature (publication dates, January 1962–October 2009) in order to identify means of mitigating adverse events that have occurred in association with the CardioWest TAH-t. We used the MEDLINE/PubMed database and searched the following MeSH terms: mechanical circulatory assist device, platelet contact with artificial surfaces, total artificial heart, Medtronic Hall valve, antithrombotic therapy, anticoagulation, and antiplatelet. References from pertinent articles were also reviewed in order to identify additional information.

Temporary Total Artificial Heart Design and Thrombogenic Profile

The CardioWest TAH-t is the culmination of decades of trial and design. Its predecessors include the Symbion Jarvik-7 100 and Symbion Jarvik-7 70 TAHs, which were developed and refined after 1950. The Jarvik and CardioWest TAHs have been used in more than 90% of all artificial-heart implantations since 1982.4,5

Flow Dynamics

The CardioWest TAH-t is a biventricular pulsatile pneumatic pump that orthotopically replaces both native ventricles and all 4 cardiac valves. The ventricular portion of the device weighs 160 g and displaces 400 mL of space in the thoracic cavity. Blood is expelled from each ventricle by pneumatic jets of compressed air that are generated by an exogenous driver. By design, each ventricle has a stroke volume of 70 mL; maximal flow produces a cardiac output of 9 L/min.3,4 Problematically, fibrinogen is displaced from hemoglobin to a greater degree as flow is increased.6,7

In a retrospective, observational case series of 14 patients in whom the Jarvik-7 70 heart was implanted, Kormos and colleagues7 evaluated the associated rheologic markers of abnormality: the erythrocyte rigidity index (a marker of whole-blood/plasma viscosity standardized for hematocrit), plasma fibrinogen, and serum haptoglobin.8 The investigators concluded that the erythrocyte rigidity index increased early after device implantation, but began returning to normal by day 14. Hyperfibrinogenemia occurred with little consistency, and serum haptoglobin was reduced in most patients. Encouragingly, longer duration of implantation was not associated with a worsening degree of hemolytic anemia.7

Biomaterial Surfaces and Blood/Plasma Reactivity

The Jarvik-7 70 and the CardioWest TAH-t are largely similar in construction and design. Each uses 4 Medtronic Hall® tilting-disc valves (Medtronic, Inc.; Minneapolis, Minn), 2 polyethylene terephthalate (Dacron) mesh and segmented polyurethane-solution ventricular housings, 4 segmented polyurethane solution-redundant blood/air diaphragms, and Dacron velour inflow and outflow grafts. The only difference between the Jarvik-7 70 and CardioWest TAH-t is the replacement of the skin button with Dacron velour, which is attached directly to the air conduits in the CardioWest TAH-t.4 Use of the aforementioned materials should yield a low risk of thrombus formation; however, mechanical circulatory assist devices (MCADs) have been associated with substantial thromboembolic phenomena despite therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin and antiplatelet therapy with dipyridamole and aspirin.6,9,10

Endogenous platelet reactivity to artificial surfaces is a complex process. Reactivity begins with a conformational change on the platelet after it encounters activated contact proteins (von Willebrand factor, factor XIIa, and high-molecular-weight kininogen) that adhere to the artificial surfaces at the glycoprotein (GP) Ib receptor.6,11 After the artificial surface is coated in a layer of activated contact proteins, it functions in a passive role. Kallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen further activate additional factor XII, resulting in continuous stimulation of the contact pathway of coagulation.12 Subsequently, platelets undergo spreading, mediated by the GPIIb/IIIa receptor that is exposed during the initial conformational change. This leads to the release of adenosine-5-diphosphate, triggering enhanced expression of GPIIb/IIIa receptors on circulating platelets. Platelet activation results in fibrinogen and fibronectin-mediated aggregation, which yields the problematic cross-linked, fibrin-rich thrombus.11 In addition, the contact-protein pathway produces larger and stronger thrombi that form more rapidly and dissolve more slowly than do those that are stimulated by the tissue-factor pathway.6

In order to evaluate the thromboembolic complications of the Jarvik-7 70 heart, Schoen and colleagues5 performed a prospective observational study of 52 patients who were implanted with the device. The patients were supported from 1 to 243 days and were given heparin, warfarin, dipyridamole, and aspirin. Only 3 thromboembolic incidents occurred during the study period. Upon device explantation, red and white thrombi were occasionally noted on the inflow cuff, outflow graft, and valves.5

In order to characterize the thromboembolic profile of the Medtronic Hall tilting-disc valve, Butchart and colleagues13 performed a prospective observational study of 2,000 implantations over 12,688 patient-years. Of these implantations, 736 were in the aortic position, 796 were in the mitral position, and 468 were dual-valve procedures. All patients were given warfarin that was titrated to an international normalized ratio (INR) goal of 2.5 and 3 for the aortic and mitral position, respectively. Fewer than half of the patients underwent concomitant therapy with dipyridamole. For all positions combined, the prevalence of stroke was low (n=34, 1.7%), as was thrombosis requiring valve replacement (n=1). Major thromboembolism occurred in only 2% of the study patients; minor thromboembolism occurred more frequently (in 9.7%) and was more often associated with valves in the mitral position (5.1%).13 In addition, Fiore and associates14 suggested that there is no difference between the St. Jude bileaflet valve (St. Jude Medical, Inc.; St. Paul, Minn) and the Medtronic Hall tilting-disc valve with respect to performance (P=0.6) or thromboembolism (P=0.56).

Multitargeted Antithrombotic Approach

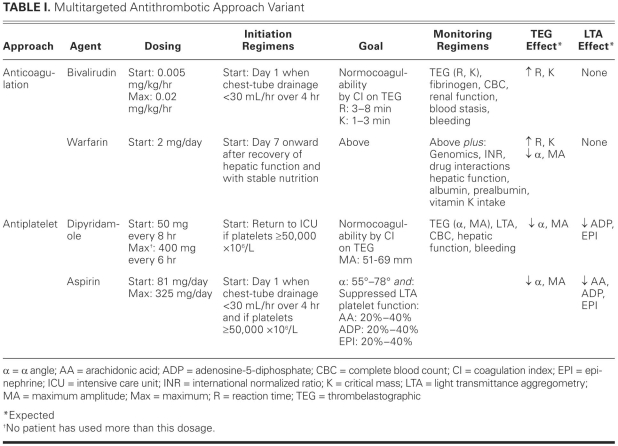

The multitargeted antithrombotic approach (MTA) is a systematic thromboprophylaxis regimen. Numerous variants of the MTA have been used in patients who have been implanted with left ventricular assist systems (including the Thoratec HeartMate® II [Thoratec Corporation; Pleasanton, Calif] and the Jarvik 2000 FlowMaker® [Jarvik Heart, Inc.; New York, NY]) and with TAHs (including the Jarvik-7 100, Jarvik-7 70, and CardioWest TAH-t).5,9,10,15–22 The original MTA, then termed the multidrug approach, was pioneered by Szefner at La Pitié Hospital for the Jarvik-7 devices and involved anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, and viscosity reduction.15,18,19 Szefner and colleagues published a prospective observational case series of 82 patients—62 of whom received the Jarvik-7 devices and 20 the CardioWest TAH-t at La Pitié Hospital—who underwent the multidrug approach and multisystem monitoring. No cerebrovascular accidents were noted during 1,930 cumulative days of TAH support.19 A similar experience was reported by Copeland and colleagues from the University of Arizona4,21: among 58 consecutive patients who underwent the multidrug approach and multisystem monitoring, 4 cerebrovascular accidents were noted during 5,408 cumulative days of TAH support. Common MTA regimens in use today are identical to that of Szefner or incorporate the first 2 strategies, anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy (Table I).4,9,10,17,18

TABLE I. Multitargeted Antithrombotic Approach Variant

Anticoagulation

Systemic anticoagulation is performed either with indirect agents (unfractionated heparin [UFH] and warfarin) or with direct agents (bivalirudin). This therapy is initiated upon the attainment of surgical hemostasis, which is defined as chest-tube output of less than 30 mL/hr over 4 hours. The intravenous component of this approach is continued until normocoagulability on warfarin therapy is achieved.4,17

Unfractionated Heparin.

Unfractionated heparin is heterogeneous with respect to molecular weight and pharmacokinetic anticoagulative properties. Approximately one third of exogenous UFH contains the unique pentasaccharide sequence that is required to mediate the conformational change in antithrombin III that creates the UFH/antithrombin complex. This complex catalyzes the inhibition of the endogenous clotting factors IIa (thrombin), VIa, VIIa, IXa, and Xa disproportionately faster than does antithrombin alone.22 Other minor anticoagulative effects, such as the inhibition of heparin cofactor II and down-regulation of factor Xa generation, require a high serum UFH concentration. The UFH is eliminated primarily by a saturable endothelial and macrophage depolymerization mechanism, and to a much lesser extent by renal clearance at therapeutic concentrations. The effective half-life of UFH is approximately 30 minutes.22 The starting dosage of UFH in the MTA is different from that of conventional use, in that no bolus is given before a continuous intravenous infusion of 2 to 5 IU/kg/hr is begun.4 The dosage is adjusted by means of thrombelastography (a monitoring method that is discussed below) in order to maintain normocoagulability (Fig. 1; Table II).4,21

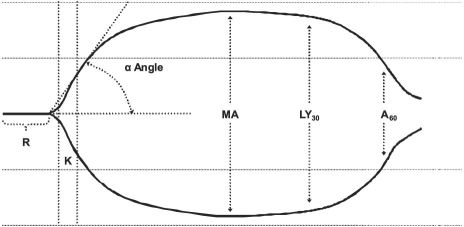

Fig. 1 Thrombelastograph tracing shows the reaction time (R), time to reach critical mass (K), α angle, maximum amplitude (MA), rate of amplitude reduction 30 min after MA (LY30), and rate of amplitude reduction 60 min after MA (A60).

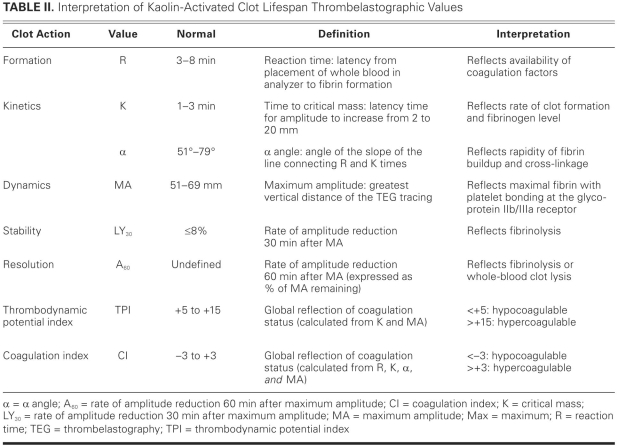

TABLE II. Interpretation of Kaolin-Activated Clot Lifespan Thrombelastographic Values

The major factor that restricts the widespread use of UFH in patients with MCADs is the unacceptably high rate of development of antiplatelet factor 4/heparin (aPF4/H) antibodies. In order to evaluate the incidence and significance of aPF4/H antibodies, Schenk and colleagues23 conducted a prospective, observational, single-center study of 126 patients who underwent MCAD support longer than 5 days. All were given perioperative anticoagulation with UFH, which was continued in the intensive care unit until phenprocoumon was therapeutic (INR=3). Few patients received concomitant aspirin or clopidogrel. Sixty-eight percent developed aPF4/H antibodies, and 42% were diagnosed with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Patients who expressed aPF4/H antibodies developed thrombus at nearly 3 times the rate of those who did not express antibodies (67% vs 23%, P <0.001), regardless of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia diagnosis. Independent risk factors for thrombus formation were identified as higher aPF4/H antibody titers (P=0.001) and higher mean fibrinogen levels (>525 mg/dL, P=0.007).23

Bivalirudin.

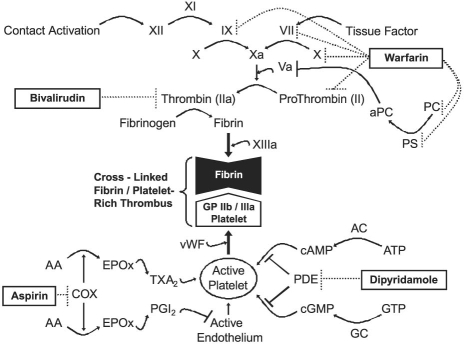

Bivalirudin, a polypeptide analog of r-hirudin, reversibly and directly binds to the active site of thrombin, rendering the thrombin ineffective (Fig. 2).22,24 Bivalirudin has several advantages over argatroban and lepirudin, the other direct thrombin inhibitors. The effective half-life of bivalirudin is approximately 25 minutes, which enables faster elimination than argatroban (45 min) and lepirudin (78 min).25 Bivalirudin is eliminated primarily by plasma esterases (80%) and to a lesser extent by renal clearance (20%); in contrast, argatroban is eliminated via the hepatic route and lepirudin by renal clearance. Accordingly, the use of bivalirudin may lead to less drug-disease and fewer drug–drug interactions. In addition, bivalirudin has little effect on surrogate markers of anticoagulation (INR), which, when compared with argatroban (large effect) and lepirudin (moderate effect) may ease a patient's transition to warfarin therapy.24 The starting dosage of bivalirudin in the MTA is different from that of conventional use, in that no bolus is given before a continuous intravenous infusion of 0.005 mg/kg/hr is begun (Table I).17,26 The dosage is adjusted by means of thrombelastography in order to maintain normocoagulability (Fig. 1; Tables I and II).17,27 Monitoring bivalirudin with ecarin and kaolin-activated thrombelastography has correlated well, both in vitro and in vivo, with traditional markers of anticoagulation, such as activated clotting time and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).17,27,28 In addition, unlike UFH, bivalirudin has negligible effects on the α angle and maximum amplitude of the thrombelastograph.27,28

Fig. 2 Mechanisms of the multitargeted antithrombotic approach are illustrated as agonist effects (→), antagonist effects (⊣), or drug effects (…|).

AA = arachidonic acid; AC = adenylate cyclase; aPC = activated protein C; ATP = adenosine triphosphate; cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cGMP = cyclic guanosine monophosphate; COX = cyclooxygenase; EPOx = endoperoxide; GC = guanylate cyclase; GP = glycoprotein; GTP = guanosine triphosphate; PC = protein C; PDE = phosphodiesterase; PGI2 = prostacyclin I2; PS = protein S; TXA2 = thromboxane A2; vWF = von Willebrand factor

Bivalirudin is the most studied of the direct thrombin inhibitors, and it is recommended as the chief alternative to UFH in cardiac surgical patients.17,24,25,29–32 Crouch and colleagues published a retrospective case series of 5 patients, implanted with the CardioWest TAH-t, who were treated with bivalirudin instead of with UFH as a systemic anticoagulant.17 All patients were given concomitant aspirin and dipyridamole, and all achieved successful transition to warfarin by the 15th day after implantation. This MTA variant was adjusted with data that were obtained from multisystem monitoring. Bivalirudin was started at 0.005 mg/kg/hr and titrated to a mean dosage of 0.015 mg/kg/hr. No patient required more than 0.02 mg/kg/hr. No thromboembolic or major hemorrhagic events occurred. Multisystem monitoring data correlated well with standard measures.17,27 Given the unacceptably high rate of aPF4/H antibody development and subsequent thrombosis in patients who are supported with MCADs, bivalirudin is a viable alternative to UFH.

Warfarin.

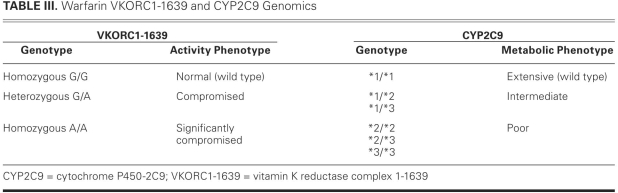

Warfarin, a coumarin derivative similar to phenprocoumon, is a racemic mixture of 2 enantiomers, S and R. It produces its anticoagulative effects by antagonizing the vitamin K reductase complex-1 (VKORC1), which is responsible for reducing vitamin K epoxide to a major cofactor in the production of the activated clotting enzymes II, VII, IX, and X (Fig. 2).33,34 Warfarin may have procoagulative action in the initial phase due to inhibition of regulatory anticoagulative proteins (C and S) carboxylation. The S enantiomer is approximately 3 times more potent than the R enantiomer, and both isomers are eliminated via cytochrome P-450 (CYP)-mediated hepatic oxidation. S-Warfarin is oxidized by CYP2C9 and has an effective half-life of 29 hours. R-Warfarin is oxidized by CYP1A2 (and, to a lesser extent, by CYP3A4) and has an effective half-life of 45 hours.33 The starting dosage of warfarin in the MTA is conservative (usually no more than 2 mg daily), and is begun only after the patient recovers hepatic function and sound nutritional status is assured (Table I). The dosage is adjusted by means of thrombelastography in order to maintain normocoagulability (Fig. 1; Tables I and II) and is guided by the results of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genomic studies (Table III).4,17,21

TABLE III. Warfarin VKORC1-1639 and CYP2C9 Genomics

Antiplatelet Therapy

The inhibition of platelet aggregation is performed with dipyridamole and aspirin therapy. Dipyridamole is initiated in the immediate postoperative phase upon a patient's arrival in the intensive care unit, and aspirin is initiated when surgical hemostasis has been attained. Both therapies require a postoperative platelet count of ≥50,000 × 106/L before initiation.4,17,21

Dipyridamole.

Dipyridamole, a pyrimido-pyrimidine derivative, produces its antiplatelet effects through 2 distinct mechanisms, the first of which is inhibition of adenosine uptake by erythrocytes and endothelial cells. This additional serum adenosine agonizes the adenylate cyclase-mediated production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and guanylate cyclase-mediated production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Both cAMP and cGMP are converted to inactive 5′-AMP and 5′-GMP by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase is dipyridamole's 2nd mechanism of action (Fig. 2). These distinct pathways result in an increase in intraplatelet concentrations of cAMP and cGMP, which are potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation.35,36 Dipyridamole is eliminated primarily through hepatic conjugation to an inactive glucuronide that is excreted in bile.37,38 The effective half-life of dipyridamole is approximately 10 hours.37 The starting dosage of dipyridamole in the MTA, 50 mg every 8 hours, differs from that of conventional use (Table I). The dosage is adjusted in order to maintain suppressed platelet coagulability on light transmittance aggregometry (LTA) and normocoagulability on thrombelastography (Fig. 1; Tables I and II).4,17,21

Aspirin.

Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) produces its antiplatelet effects through the irreversible inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) prostaglandin H-synthase-1 and -2–mediated conversion of arachidonic acid to endoperoxide. This results in down-regulation of the synthesis of both thromboxane A2 (responsible for platelet activation) and prostacyclin I2 (responsible for endothelial deactivation) from endoperoxide (Fig. 2). The thrombogenic potential of the COX-2 selective antagonists rofecoxib and celecoxib suggests that endogenous prostacyclin I2 production is an important mechanism of thromboresistance. Due to long-term shear stress, the COX-2–mediated generation of prostacyclin I2 is largely insensitive to aspirin at commonly used doses.35,36 Aspirin is eliminated by degradation to acetic and salicylic acids in the gut. The effective duration of action of aspirin is the lifespan of each platelet, approximately 8 to 10 days. Recovery of thromboxane A2 generation is faster than the rate of platelet turnover after prolonged therapy; however, this action should not substantially affect the antiplatelet effects of aspirin.35 The starting dosage of aspirin in the MTA, a conservative 81 mg daily, is adjusted in order to maintain suppressed platelet coagulability on LTA and normocoagulability on thrombelastography (Fig. 1; Tables I and II).4,17,21

Viscosity Reduction

Pentoxifylline.

Pentoxifylline, a xanthine derivative, is a hemorheologic agent that purportedly increases peripheral oxygen delivery by decreasing blood viscosity and platelet adhesiveness, possibly decreasing fibrinogen concentration, and increasing erythrocyte deformity. Little evidence of quality supports any of these postulated mechanisms, because the data are largely from animal and in vitro studies.39–42 Due to this lack of evidence, the American College of Chest Physicians' 7th (2004) and 8th (2008) conferences on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy have consistently recommended against pentoxifylline for patients who have peripheral arterial occlusive disease.40,41 Pentoxifylline undergoes significant 1st-pass erythrocyte metabolism, producing active secondary xanthines, which are eliminated renally. The effective half-life of pentoxifylline and its metabolites is approximately 1 hour.39 The dosage of pentoxifylline in the MTA is similar to that of conventional use: 200 to 400 mg, 3 times daily.4,21

Monitoring the Multitargeted Antithrombotic Approach

By themselves, conventional surrogate markers of anticoagulation (such as prothrombin time and aPTT) are less-than-optimal means of monitoring the complex antithrombotic actions that occur during the MTA. Szefner's experience with the multidrug approach yielded a sound system of precise monitoring tools that describe actual blood–plasma rheology and coagulation, termed multisystem monitoring. Szefner first incorporated 2 monitoring approaches: antithrombotic efficacy tests and safety tests. The efficacy tests include thrombelastography, optical platelet aggregometry, platelet count, D-dimer, bleeding time, prothrombin time, aPTT, and fibrinogen level. The safety tests include laboratory analyses to evaluate bleeding (hemoglobin and hematocrit), hepatic function (aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, total and conjugated bilirubin, total serum protein, and albumin), renal function (blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine), hemolytic anemia (lactate dehydrogenase and haptoglobin), and nutritional status (prealbumin).4,21

Common MTA monitoring regimens in use today are identical to Szefner's, or they are variants that use modified or additional approaches.4,17,21 One such variant monitoring system in use at the Virginia Commonwealth University Health System includes modified efficacy testing that involves thrombelastography, LTA, platelet count, D-dimer, INR, aPTT, and fibrinogen level. It also includes the same safety tests and an additional approach, warfarin genomics.34

Thrombelastography

Since its discovery in 1942, thrombelastography has been used sporadically in cardiac surgery to guide perioperative blood-product administration and to manage coagulopathies after a patient undergoes cardiopulmonary bypass.43–48 The thrombelastograph (TEG®; Haemoscope Corporation; Niles, Ill) is generated by an electronically transduced pin that is suspended by a torsion wire in a heated (37°C) and oscillating (4° every 4.5 sec) cup of 0.35 mL of kaolin-activated whole blood (Fig. 1). Initially, the liquid blood does not transfer any motion to the torsion wire; this is manifested as zero amplitude on the TEG. Over time, blood coagulation thromboses the pin to the cup, transfers the oscillating motion directly to the torsion wire, and increases the amplitude of the TEG. As fibrinolysis or whole-blood clot lysis occurs, the cup moves independently of the pin and the amplitude of the TEG returns to zero.45,46 The TEG describes 5 phases of a clot's lifespan: formation, kinetics, dynamics, stability, and resolution (Table II). Components of the MTA affect the TEG values differently (Table I). Clot formation (R) and kinetics (K) are affected predominantly by the anticoagulation approach. Clot kinetics (α) and dynamics (MA) are affected predominantly by the antiplatelet approach. The effects, if any, of viscosity reduction on thrombelastographic values have not been studied.

There are 2 TEG-calculated global measures of coagulation status: the thrombodynamic potential index (TPI) and the coagulation index (CI) (Table II). The TPI reflects the kinetic and dynamic properties of clot generation and is calculated by standardizing the clot's shear modulus (ɛ) by the time to critical mass (K), using the following equation: TPI = ɛ/K, where ɛ = (100MA)/(100 − MA).21,48 In comparison with the TPI, the CI reflects more of the clot's lifespan, including formation, kinetic, and dynamic properties; accordingly, CI may be the superior measure of global coagulation status. The CI is calculated using the following equation: CI = −0.3258R − 0.1886K + 0.0759α + 0.1224MA − 7.7922.17,44,45,49

Light Transmittance Aggregometry

Light transmittance aggregometry has been widely used in specialty laboratories since its discovery in 1962, and it is recognized as the gold standard of platelet-aggregation tests.38,50–52 This monitoring method requires a large volume of blood and a skilled operator to interpret the results that are generated by the labor-intensive analyzer. One such analyzer is the PAP-4® platelet-aggregation profiler (Bio/Data Corporation; Horsham, Pa). The LTA is performed on platelet-rich plasma, which is obtained by centrifuging whole blood under significant G forces over time (for example, at 2,200 G/min for 30 sec), under low-shear conditions by the turbidimetric method. Aggregation is stimulated by conventional agonists, such as arachidonic acid, adenosine-5-diphosphate, epinephrine, and collagen.4,50–52 Historically, the platelet-rich plasma has been standardized for the actual plasma platelet count; however, this practice provides no advantage over the use of nonstandardized platelet-rich plasma and is not routinely performed in coagulation laboratories today.53

Several investigators have criticized LTA for not accurately simulating the shear adhesion and stress activation of coagulation after vessel-wall damage (tissue-factor pathway). However, MCADs stimulate platelet aggregation through the contact-activation pathway; and although shear and stress exist in the LTA analyzer, the degree of simulative accuracy of these forces by LTA has not been studied. Alternative aggregators have been developed that may more closely mimic shear and stress forces, such as impedance whole-blood aggregometry, as performed on the PFA-100® System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.; Deerfield, Ill) or on the VerifyNow® System (Accumetrics, Inc.; San Diego, Calif).50,51 Whole-blood aggregometry analyzers are widely used in coagulation laboratories but have not been studied in TAH support.

Warfarin Genomics

The dosing and titration of warfarin are influenced by nongenetic and genetic factors. Nongenetic factors include nutritional deficit, hepatic impairment, drug interactions, anemia, and coagulation status. Some genetic factors, including the target (VKORC1) and major route of elimination (CYP2C9) of warfarin, vary substantially across the population.34,54 Accordingly, Schwarz and colleagues34 performed a 2-year prospective cohort study to evaluate the effect of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 alleles on the INR over time. The primary outcomes were time to 1st therapeutic INR and time to 1st supratherapeutic INR (INR >4). Times to 1st therapeutic INR (7 vs 15 d, P=0.003) and supratherapeutic INR (17 vs 23 d, P=0.02) were significantly shorter in patients who expressed the non-wild VKORC1 genotypes (Table III). Time to 1st therapeutic INR was not different (P=0.57); however, time to 1st supratherapeutic INR was significantly shorter (18 vs 22 d, P=0.03) in patients who expressed the non-wild CYP2C9 genotypes (Table III). Eight major and 5 minor unique bleeding episodes occurred in 12 patients during the study period. Of these 12 patients, 9 expressed non-wild VKORC1 genotypes and 6 expressed non-wild CYP2C9 genotypes.34

Summary and Recommendations

The CardioWest TAH-t is a viable bridge to OHT for patients who are experiencing end-stage refractory biventricular heart failure; however, the device is associated with a low but still substantial risk of thrombosis. Platelet interactions with artificial surfaces are complex and result in continuous activation of contact proteins despite therapeutic anticoagulation. Judicious use of an MTA variant with the application of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy may mitigate the procoagulative effects of MCADs, particularly those that are associated with the CardioWest TAH-t. We believe that the viscosity-reduction approach provides no additional benefit over anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. Careful monitoring via efficacy tests, safety tests, and genomics can maximize the therapeutic actions and minimize the risks of bleeding that are associated with the MTA. We propose that LTA be used preferentially over conventional platelet aggregometry or impedance whole-blood aggregometry, because LTA is the gold standard, and it has been used with success in TAH support. Finally, we believe that the development and monitoring of individualized MTA regimens requires that educated health professionals appreciate the complexities and understand the hazards that are associated with these therapies.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Christopher R. Ensor, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy, Comprehensive Transplant Center, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 N. Wolfe St., Carnegie 180, Baltimore, MD 21287-6180

E-mail: censor1@jhmi.edu

Dr. Kasirajan is a consultant to SynCardia Systems, Inc. (Tucson, Ariz), the manufacturer of the CardioWest device. Dr. Crouch has received honoraria from The Medicines Company (Parsippany, NJ) for Continuing Education programs that included discussion of bivalirudin.

References

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2005;112(12):e154–235. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.2001 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Vol. 1. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources & Services Administration, Office of Special Programs, Division of Transplantation; Rockville, MD. p. 439–83.

- 3.Copeland JG, Smith RG, Arabia FA, Nolan PE, Sethi GK, Tsau PH, et al. Cardiac replacement with a total artificial heart as a bridge to transplantation. N Engl J Med 2004;351(9): 859–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Copeland JG, Arabia FA, Tsau PH, Nolan PE, McClellan D, Smith RG, Slepian MJ. Total artificial hearts: bridge to transplantation. Cardiol Clin 2003;21(1):101–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Schoen FJ, Clagett GP, Hill JD, Chenoweth DE, Anderson JM, Eberhart RC. The biocompatibility of artificial organs. ASAIO Trans 1987;33(4):824–33. [PubMed]

- 6.Nielsen VG, Kirklin JK, Holman WL, Steenwyk BL, George JF, Zhou F, et al. Mechanical circulatory device thrombosis: a new paradigm linking hypercoagulation and hypofibrinolysis. ASAIO J 2008;54(4):351–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kormos RL, Borovetz HS, Griffith BP, Hung TC. Rheologic abnormalities in patients with the Jarvik-7 total artificial heart. ASAIO Trans 1987;33(3):413–7. [PubMed]

- 8.Dintenfass L. Red cell rigidity, “Tk,” and filtration. Clin Hemorheol 1985;5:241–4.

- 9.Amir O, Bracey AW, Smart FW, Delgado RM 3rd, Shah N, Kar B. A successful anticoagulation protocol for the first HeartMate II implantation in the United States. Tex Heart Inst J 2005;32(3):399–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Myers TJ, Robertson K, Pool T, Shah N, Gregoric I, Frazier OH. Continuous flow pumps and total artificial hearts: management issues. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75(6 Suppl):S79–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Joist JH, Pennington DG. Platelet reactions with artificial surfaces. ASAIO Trans 1987;33(3):341–4. [PubMed]

- 12.Guo Z, Bussard KM, Chatterjee K, Miller R, Vogler EA, Siedlecki CA. Mathematical modeling of material-induced blood plasma coagulation. Biomaterials 2006;27(5):796–806. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Butchart EG, Li HH, Payne N, Buchan K, Grunkemeier GL. Twenty years' experience with the Medtronic Hall valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121(6):1090–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fiore AC, Barner HB, Swartz MT, McBride LR, Labovitz AJ, Vaca KJ, et al. Mitral valve replacement: randomized trial of St. Jude and Medtronic Hall prostheses. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66(3):707–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Szefner J, Cabrol C. Control and treatment of hemostasis in patients with a total artificial heart: the experience of La Pitié. In: Pifarré R, editor. Anticoagulation, hemostasis, and blood preservation in cardiovascular surgery. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; Mosby (distributor); 1993. p. 237–64.

- 16.Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Boyle AJ, Aaronson KD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007;357(9): 885–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Crouch MA, Kasirajan V, Cahoon W, Katlaps GJ, Gunnerson KJ. Successful use and dosing of bivalirudin after temporary total artificial heart implantation: a case series. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28(11):1413–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Nolan PE, Arabia FA, Smith RG, Sethi GK, Bose RK, Banchy ME, et al. Stroke outcomes following implantation of the CardioWest total artificial heart [abstract]. ASAIO J 2002;48(2): 145.

- 19.Szefner J. Control and treatment of hemostasis in cardiovascular surgery. The experience of La Pitié Hospital with patients on total artificial heart. Int J Artif Organs 1995;18(10):633–48. [PubMed]

- 20.Glauber M, Szefner J, Senni M, Gamba A, Mamprin F, Fiocchi R, et al. Reduction of haemorrhagic complications during mechanically assisted circulation with the use of a multi-system anticoagulation protocol. Int J Artif Organs 1995;18(10): 649–55. [PubMed]

- 21.Copeland JG, Arabia FA, Smith RG, Sethi GK, Nolan PE, Banchy ME. Arizona experience with CardioWest Total Artificial Heart bridge to transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 68(2):756–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hirsh J, Bauer KA, Donati MB, Gould M, Samama MM, Weitz JI; American College of Chest Physicians. Parenteral anticoagulants: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition) [published erratum appears in Chest 2008;134(2):473]. Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):141S–159S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Schenk S, El-Banayosy A, Prohaska W, Arusoglu L, Morshuis M, Koester-Eiserfunke W, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients receiving mechanical circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131(6):1373–81.e4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, Koster A, Lincoff AM; American College of Chest Physicians. Treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):340S–380S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Stratmann G, deSilva AM, Tseng EE, Hambleton J, Balea M, Romo AJ, et al. Reversal of direct thrombin inhibition after cardiopulmonary bypass in a patient with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Anesth Analg 2004;98(6):1635–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Angiomax (bivalirudin) for injection [package insert]. The Medicines Company; Parsippany, NJ. 2005 Dec 6 [cited 2010 Mar 8]. Available from: http://www.angiomax.com/Files/SalesAidRef/PI.pdf.

- 27.Koster A, Buz S, Krabatsch T, Dehmel F, Hetzer R, Kuppe H, Dyke C. Monitoring of bivalirudin anticoagulation during and after cardiopulmonary bypass using an ecarin-activated TEG system. J Card Surg 2008;23(4):321–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nielsen VG, Steenwyk BL, Gurley WQ, Pereira SJ, Lell WA, Kirklin JK. Argatroban, bivalirudin, and lepirudin do not decrease clot propagation and strength as effectively as heparin-activated antithrombin in vitro. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25(6):653–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Dyke CM, Smedira NG, Koster A, Aronson S, McCarthy HL 2nd, Kirshner R, et al. A comparison of bivalirudin to heparin with protamine reversal in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: the EVOLUTION-ON study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131(3):533–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Smedira NG, Dyke CM, Koster A, Jurmann M, Bhatia DS, Hu T, et al. Anticoagulation with bivalirudin for off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: the results of the EVOLUTION-OFF study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131(3): 686–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Koster A, Dyke CM, Aldea G, Smedira NG, McCarthy HL 2nd, Aronson S, et al. Bivalirudin during cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with previous or acute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and heparin antibodies: results of the CHOOSE-ON trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83(2):572–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Dyke CM, Aldea G, Koster A, Smedira N, Avery E, Aronson S, et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass with bivalirudin for patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or antiplatelet factor four/heparin antibodies. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84(3):836–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G; American College of Chest Physicians. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):160S–198S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Schwarz UI, Ritchie MD, Bradford Y, Li C, Dudek SM, Frye-Anderson A, et al. Genetic determinants of response to warfarin during initial anticoagulation. N Engl J Med 2008;358 (10):999–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Patrono C, Baigent C, Hirsh J, Roth G; American College of Chest Physicians. Antiplatelet drugs: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):199S–233S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Pettigrew LC. Antithrombotic drugs for secondary stroke prophylaxis. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21(4):452–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Dipyridamole injection USP [package insert]. Bedford Laboratories; Bedford, Oh. 2007 Dec [cited 2010 Mar 8]. Available from: http://www.bedfordlabs.com/BedfordLabsWeb/products/inserts/DPP06.pdf.

- 38.Gladding P, Webster M, Ormiston J, Olsen S, White H. Antiplatelet drug nonresponsiveness [published erratum appears in Am Heart J 2008;156(3):563]. Am Heart J 2008;155(4):591–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Trental (pentoxifylline) tablet, film coated [package insert]. sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; Bridgewater, NJ. 2006 Sep [cited 2010 Mar 8]. Available from: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=8411.

- 40.Clagett GP, Sobel M, Jackson MR, Lip GY, Tangelder M, Verhaeghe R. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral arterial occlusive disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004;126(3 Suppl):609S–626S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Sobel M, Verhaeghe R; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for peripheral artery occlusive disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):815S–843S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Scheffler P, de la Hamette D, Gross J, Mueller H, Schieffer H. Intensive vascular training in stage IIb of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. The additive effects of intravenous prostaglandin E1 or intravenous pentoxifylline during training. Circulation 1994;90(2):818–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.MacLaren R. Key concepts in the management of difficult hemorrhagic cases. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27(9 Pt 2):93S–102S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Luddington RJ. Thrombelastography/thromboelastometry. Clin Lab Haematol 2005;27(2):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Mallett SV, Cox DJ. Thrombelastography. Br J Anaesth 1992; 69(3):307–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Salooja N, Perry DJ. Thrombelastography [published erratum appears in Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2002;13(1):75]. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2001;12(5):327–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Spiess BD. Thromboelastography and cardiopulmonary bypass. Semin Thromb Hemost 1995;21 Suppl 4:27–33. [PubMed]

- 48.Spiess BD, Gillies BS, Chandler W, Verrier E. Changes in transfusion therapy and reexploration rate after institution of a blood management program in cardiac surgical patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1995;9(2):168–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Harnett MJ, Bhavani-Shankar K, Datta S, Tsen LC. In vitro fertilization-induced alterations in coagulation and fibrinolysis as measured by thromboelastography. Anesth Analg 2002; 95(4):1063–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Harrison P, Frelinger AL 3rd, Furman MI, Michelson AD. Measuring antiplatelet drug effects in the laboratory. Thromb Res 2007;120(3):323–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Wang TH, Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: an emerging clinical entity. Eur Heart J 2006;27(6): 647–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Ramirez C, Sabate M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, et al. Influence of aspirin resistance on platelet function profiles in patients on long-term aspirin and clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2006;97(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Linnemann B, Schwonberg J, Mani H, Prochnow S, Lindhoff-Last E. Standardization of light transmittance aggregometry for monitoring antiplatelet therapy: an adjustment for platelet count is not necessary. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6(4):677–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, Nickerson DA, Eby CS, McLeod HL, et al. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(22):2285–93. [DOI] [PubMed]