Abstract

Background:

Psychologic factors affect how patients with COPD respond to attempts to improve their self-management skills. Learned helplessness may be one such factor, but there is no validated measure of helplessness in COPD.

Methods:

We administered a new COPD Helplessness Index (CHI) to 1,202 patients with COPD. Concurrent validity was assessed through association of the CHI with established psychosocial measures and COPD severity. The association of helplessness with incident COPD exacerbations was then examined by following subjects over a median 2.1 years, defining COPD exacerbations as COPD-related hospitalizations or ED visits.

Results:

The CHI demonstrated internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.75); factor analysis was consistent with the CHI representing a single construct. Greater CHI-measured helplessness correlated with greater COPD severity assessed by the BODE (Body-mass, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise) Index (r = 0.34; P < .001). Higher CHI scores were associated with worse generic (Short Form-12, Physical Component Summary Score) and respiratory-specific (Airways Questionnaire 20) health-related quality of life, greater depressive symptoms, and higher anxiety (all P < .001). Controlling for sociodemographics and smoking status, helplessness was prospectively associated with incident COPD exacerbations (hazard ratio = 1.31; P < .001). After also controlling for the BODE Index, helplessness remained predictive of COPD exacerbations among subjects with BODE Index ≤ median (hazard ratio = 1.35; P = .01), but not among subjects with higher BODE Index values (hazard ratio = 0.93; P = .34).

Conclusions:

The CHI is an internally consistent and valid measure, concurrently associated with health status and predictively associated with COPD exacerbations. The CHI may prove a useful tool in analyzing differential clinical responses mediated by patient-centered attributes.

COPD is one of the top five causes of death and disability worldwide; its share of such morbidity and mortality is expected to increase over the coming decades.1,2 COPD often involves a progressively deteriorating health status punctuated by intermittent exacerbations characterized by wheezing, cough, and prolonged dyspnea.2 Patient self-management is believed to be a key element of successful COPD treatment, as better self-management skills may help to reduce the severity or frequency of exacerbations, prevent hospitalizations, and generally improve health-related quality of life (HRQL).3,4 However, self-management practices in COPD can be complex and burdensome and thus require significant commitment from the patient.5 For example, COPD self-management can include breathing and coughing techniques, appropriately timed oxygen usage (eg, with exercise only, during sleep only, different flow rates with exercise and rest), smoking cessation, regular exercise as prescribed through pulmonary rehabilitation, and the self-initiation of prescription corticosteroids or antibiotics at the onset of a COPD exacerbation.3,4

Psychologic factors play a role in how well patients respond to attempts to improve their self-management skills in COPD.6 Learned helplessness theory has particular relevance in providing insights into such psychologic factors. This theoretical construct posits that unpredictable and uncontrollable adverse events, such as COPD exacerbations, may instill in patients a sense of helplessness associated with feelings of passive resignation.7-9 Such helplessness may not only lead to psychologic symptoms but also decreased problem-solving. Learned helplessness could help to explain why some patients lose the motivation and initiative to adhere to the complex therapies in COPD.

Although learned helplessness is related to self-efficacy, in that both assign a prominent role to self-referent thoughts as influencing psychologic functioning, the two constructs are conceptually distinct.10 Self-efficacy refers to specific behaviors or specific circumstances, whereas learned helplessness refers more broadly to general perceptions and feelings that outcomes are not under one’s control.11 For example, the COPD self-efficacy scale asks respondents to rate how confident they are in managing their breathing difficulty in each of 34 different scenarios, such as “When there is humidity in the air” or “When I go up stairs too fast.”12 In contrast, helplessness is meaningful across a broad range of circumstances relevant to COPD. Moreover, patients’ sense of helplessness may influence the extent to which they respond to attempts to improve their self-efficacy.13,14

There is currently no COPD-specific questionnaire instrument that measures helplessness in a way that allows its role in patient-centered outcomes to be assessed systematically. Therefore, we developed and tested the performance characteristics of the COPD Helplessness Index (CHI). We hypothesized that the CHI would be an internally consistent and valid measure of helplessness in COPD. We sought to demonstrate concurrent validity by demonstrating the CHI’s cross-sectional correlation with psychosocial and clinical status measures, such as depressive symptoms and COPD severity, that should be associated with helplessness.15,16 We examined predictive validity by investigating whether the CHI was predictive of subsequent COPD-related hospitalizations and ED visits.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We conducted a cohort study of 1,212 patients with COPD who completed structured telephone interviews followed by research clinic visits. Patient recruitment is described in further detail in the online supplement and has previously been described in detail.17 Briefly, key inclusion criteria were that patients be members of Kaiser Permanente (KP), be 40 to 65 years old, live within 30 miles of our research clinic, and have been recently treated for COPD.17 First, we identified all patients, using KP databases, who met both of two criteria for COPD: (1) health-care use: having ≥ 1 ambulatory visits, ED visits, or hospitalizations over the prior 12 months with a principal diagnostic code for COPD (International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition [ICD-9] codes 491, 492, or 496), and (2) medication prescription: having ≥ 2 prescriptions for a COPD-related medication during a 12-months window around the index use date. Second, a diagnosis of COPD was confirmed, based on interviews and spirometry, using Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease criteria.18 This algorithm was previously validated using medical record review.19 The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute’s institutional review board. All participants provided informed consent.

Measurements

Items for the COPD Helplessness Index (CHI) were adapted from the Arthritis Helplessness Index.9 These questions, shown in Table 2, were administered during structured telephone interviews. In the online supplement, further details can be found regarding development and scoring of the CHI as well as other methodologies used in this study.

Table 2.

—Psychometric Information for COPD Helplessness Index: Item-Total Correlations and Response Rates

| Response Frequencies (%)a |

|||||||

| Item-Total Correlation | SA | A | N | D | SD | ||

| 1. | Managing my breathing problems is largely my own responsibility.b | 0.36 | 40 | 55 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2. | I can reduce my breathing problems by staying calm and relaxed.b | 0.34 | 24 | 56 | 11 | 7 | 2 |

| 3. | Too often, my breathing problems just seem to hit me from out of the blue. | 0.48 | 11 | 31 | 7 | 38 | 13 |

| 4. | If I do all the right things, I can successfully manage my breathing problems.b | 0.60 | 20 | 55 | 11 | 10 | 3 |

| 5. | I can do a lot of things myself to cope with my breathing problems.b | 0.58 | 22 | 66 | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| 6. | My breathing problems are controlling my life. | 0.60 | 12 | 22 | 7 | 35 | 25 |

| 7. | When it comes to managing my breathing problems, I feel I can only do what my doctor tells me to do. | 0.39 | 6 | 21 | 7 | 52 | 15 |

| 8. | When I manage my personal life well, my breathing problems do not affect me as much.b | 0.43 | 10 | 55 | 15 | 15 | 5 |

| 9. | I have considerable ability to control my breathing problems.b | 0.63 | 13 | 56 | 13 | 12 | 5 |

| 10. | I would feel helpless if I couldn’t rely on other people for help when I’m not feeling well because of my breathing problems. | 0.41 | 6 | 22 | 6 | 50 | 17 |

| 11. | Usually I can tell when my breathing problems are going to get worse.c | 0.25 | 14 | 55 | 8 | 19 | 4 |

| 12. | No matter what I do or how hard I try, I just can’t seem to get relief from my breathing problems. | 0.64 | 5 | 19 | 8 | 52 | 17 |

| 13. | I am coping effectively with my breathing problems.b | 0.53 | 18 | 68 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| 14. | It seems as though fate and other factors beyond my control affect my breathing problems. | 0.51 | 7 | 28 | 9 | 45 | 11 |

| 15. | I want to learn as much as I can about my breathing problems.b,c | 0.12 | 34 | 57 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

Response options: SA = strongly agree; A = agree; N = neutral; D = disagree; SD = strongly disagree. Items may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

Items 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 13, and 15 are reverse-scored.

Items 11 and 15 were excluded from final scale because of low item-total correlation.

A critical test of a scale’s validity is its relationship to other theoretically relevant constructs.20,21 Various psychosocial, HRQL, and COPD severity measures were thus used to test the CHI’s concurrent validity. Generic physical HRQL was measured using the Short-Form-12 Physical Component Summary score.22 Respiratory-specific HRQL was assessed using the revised Airways Questionnaire 20 (AQ20-R).23-25 Depressive symptoms were obtained using the 15-item short-form Geriatric Depression Scale, which has been validated in nongeriatric populations generally, as well as specifically in younger adults with obstructive lung disease.26-28 Anxiety was assessed using the seven-item anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.29,30 COPD severity was assessed with the Body-mass, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise (BODE) Index, a multidimensional score which includes FEV1, 6-min walk test, BMI, and dyspnea.31

To examine predictive validity, we determined the prospective association of the CHI with COPD-related emergency health-care use, a proxy for acute COPD exacerbations. Although there is no uniformly accepted definition of acute COPD exacerbations,32 hospitalization or ED visit for COPD is often used for research purposes.33,34 COPD-related hospitalization was defined as one or more hospitalizations with primary discharge diagnosis code for COPD (ICD-9 codes 491, 492, or 496), whereas COPD-related ED visit was defined as one or more ED visits with such an ICD-9 code for COPD. The median duration of follow-up was 2.1 years (25th-75th interquartile range: 1.7-2.6 years).

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated the internal consistency of the CHI by computing Cronbach α and evaluated its homogeneity by conducting a principal components analysis to examine factor loading on the generated eigenvalues.35 Questions on the CHI with item-total correlations < 0.3 were eliminated from the final scale.35 In examining cross-sectional concurrent validity, we used Pearson correlations to test the association of the CHI with the aforementioned relevant constructs. To take into account potential confounding, we also performed additional analyses in which we retested each measure’s relationship to the CHI using multivariable linear regression. Here, we developed separate multivariable linear regression models, each with the CHI as the dependent variable but with a different HRQL, psychologic, or COPD severity measure as an independent variable. For all of these models, we also included age, gender, race-ethnicity, marital status, education, and smoking status as independent variables. For longitudinal emergency health-care outcomes (COPD exacerbations), we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. In one set of analyses, we adjusted for the potentially confounding sociodemographic factors listed above and smoking status. In a second set of analyses, we also adjusted for the BODE Index. Finally, because we anticipated that helplessness may be differentially associated with adverse COPD outcomes depending on the level of COPD severity, we repeated the second analysis after dichotomizing subjects into either low or high COPD severity based on the median BODE Index values of the cohort. All analyses used Stata/SE version 9.2 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

Results

Subject Characteristics

The mean subject age was 58.2 (SD = 6.2 years), and 57% of subjects were women. Additional characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

—Characteristics of 1,202 Patients With COPD

| No. (%) or Mean ± SD | |

| Age, y | 58.2 ± 6.2 |

| Female gender | 691 (57) |

| Married or cohabiting | 744 (62) |

| College graduate | 326 (27) |

| White non-Latino | 810 (67) |

| Tobacco status | |

| Never smoker | 165 (14) |

| Former smoker | 644 (54) |

| Current smoker | 393 (33) |

| BODE Index | 2.9 ± 2.4 |

| COPD Helplessness Index | 17.5 ± 6.8 |

BODE = Body Mass, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise.

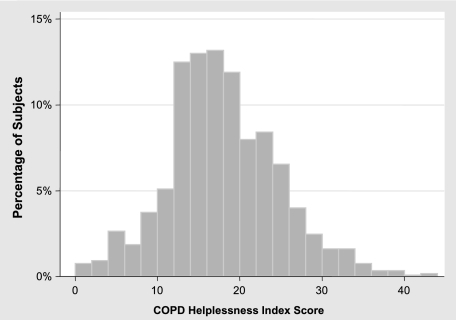

CHI Distribution, Internal Consistency, and Homogeneity

The CHI items and their response frequencies are shown in Table 2. Two items (11 and 15) demonstrated low item-total correlations and were eliminated from further analysis, leaving a 13-item score. After removal of items 11 and 15, item-total correlations for the remaining items ranged from 0.32 to 0.66. The possible score range of the 13-item CHI was 0 to 52. Observed scores ranged from 0 to 44, with a median of 17, a mean of 17.5, and a standard deviation of 6.8 (Fig 1). Higher scores reflect greater helplessness.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the COPD Helplessness Index among 1,202 subjects with COPD.

The Cronbach α for the 13-item scale was 0.75, indicative of an internal consistency sufficient for group analyses. In a principal components analysis, the eigenvalue for the first principal component was 3.52, declining sharply to 1.63 for the second component and then declining gradually to 0.47 by the 13th component. All of the items weighted positively on the first component (weights ranging from 0.32 to 0.68). Together, this principal component analysis is consistent with the 13 items homogenously representing a single construct.

Concurrent Validity

As shown in Table 3, higher CHI scores were associated with worse health status for all HRQL and psychologic measures. CHI scores also correlated in the expected direction with COPD severity, as assessed by the BODE Index and its individual components (Table 3).

Table 3.

—Bivariate Correlations of Health-Related Quality-of-Life, Psychologic, and COPD Severity Factors With the COPD Helplessness Index

| Factors Associated with CHI | Mean ± SD | Correlation with CHI r | P Value |

| HRQL and psychologic factors | |||

| Overall physical HRQL (SF-12 PCS)a | 38.3 ± 11.2 | −0.42 | < .001 |

| Respiratory-specific HRQL (AQ20-R)b | 8.9 ± 4.6 | 0.54 | < .001 |

| Depression scale (GDS)b | 4.0 ± 3.6 | 0.55 | < .001 |

| Anxiety scale (HADS–anxiety subscale)b | 4.4 ± 4.0 | 0.41 | < .001 |

| COPD severity | |||

| BODE Index (total)b | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 0.34 | < .001 |

| Selected BODE components | |||

| FEV1 % predicteda | 62.4 ± 23.3 | −0.11 | < .001 |

| MMRC dyspnea scaleb | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 0.45 | < .001 |

| 6-min walk test, ma | 403 ± 120 | −0.25 | < .001 |

AQ20-R = Airways Questionnaire 20, Revised; CHI = COPD Helplessness Index; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; HRQL = health-related quality of life; MMRC = Modified Medical Research Council; PCS = Physical Component Summary; SF-12 = Short Form-12. See Table 1 for expansion of other abbreviations.

Higher SF-12 PCS scores, higher FEV1% predicted, and greater distance walked on the 6-min walk test reflect better health status.

Higher AQ20-R, GDS, HADS, MMRC Dyspnea Scale, and BODE Index scores reflect worse health status. (FEV1 and the 6-min walk test are reverse scored for the summary BODE Index.)

To assess for potential confounding in these correlations, we also performed additional analyses in which we developed multivariable linear regression models to account for the potential confounding by sociodemographics and smoking status on the relationship between the CHI and each HRQL factor, psychologic factor, and COPD severity factor. In every case, the factors remained statistically related to the CHI (P < .001) (data shown in online supplement).

Predictive Validity

Here we examined whether helplessness was prospectively associated with emergency health-care use for COPD, which was our proxy for acute exacerbations of COPD and was defined as the combined end point of either an ED visit or hospitalization related to COPD, as described above. In follow-up over a median 2.1 years, there were 76 hospitalizations and 244 ED visits for COPD. In analysis adjusted for sociodemographic factors and smoking status, for every standard deviation increase in CHI score, the risk of emergency health-care use increased by 31% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.31; P < .001). After also adjusting for the BODE Index as a measure of COPD severity, helplessness was no longer statistically significantly associated with emergency health-care use in the cohort as a whole (HR, 1.05; P = .45). However, as shown in Table 4, when subjects were dichotomized into those with less severe COPD (BODE Index ≤ median) or more severe COPD (BODE Index > median) and multivariable analyses controlled for sociodemographics, smoking status, and the BODE Index itself, the CHI was prospectively associated with emergency health-care use among those with less severe COPD (HR, 1.35; P = .01), but not among subjects with more severe COPD (HR, 0.93; P = .34).

Table 4.

—Prospective Association of Helplessness With COPD-Related Emergency Health-Care Use, Controlling for Sociodemographics, Smoking Status, and COPD Severity (BODE Index): Multivariable Analysis Stratified by COPD Severity

| Low COPD Severity (BODE ≤ Median)an = 738 |

High COPD Severity (BODE > Median)an = 464 |

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age,b y | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | .001 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .89 |

| Female gender | 0.8 (0.6-1.3) | .43 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | .46 |

| Married or cohabiting | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | .48 | 0.7 (0.5-1.02) | .07 |

| College graduate | 0.5 (0.3-0.96) | .036 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | .72 |

| White non-Latino | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) | .89 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | .16 |

| Tobacco status | ||||

| Never smoker | 1.0 [Reference] | N/A | 1.0 [Reference] | N/A |

| Former smoker | 1.8 (0.7-4.2) | .20 | 4.2 (1.8-9.6) | .001 |

| Current smoker | 2.9 (1.2-7.0) | .017 | 3.8 (1.6-8.9) | .002 |

| BODE Indexc | 2.35 (1.5-3.7) | < .001 | 1.87 (1.5-2.4) | < .001 |

| CHIc | 1.35 (1.1-1.7) | .010 | 0.93 (0.8-1.1) | .34 |

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis included all covariates listed above. COPD-related emergency health-care use was our proxy for acute exacerbations of COPD and was defined as the combined end point of either a COPD-related hospitalization or an ED visit. P values < .05 are in boldface type. HR = hazard ratio; N/A = not applicable. See Tables 1 and 3 for expansion of other abbreviations.

BODE Index median = 3 on a possible scale of 0 to 10.

HR expressed per 5-y increment in age.

HRs are expressed per 1 standard deviation increment in CHI and BODE Index, both of which represent worse health status.

Discussion

These results support our primary hypothesis that helplessness is a valid construct in COPD, as it is associated concurrently with measures of disease severity, psychologic health status, and HRQL and prospectively with important health outcomes, all in the expected directions. The CHI is internally consistent, with performance characteristics indicating that it reflects a single domain. Moreover, the 13-item battery can be administered efficiently as a brief survey instrument.

Our theoretical model proposes that higher degrees of helplessness are associated with feelings of passive resignation, which lead to poorer self-management. Theoretically, helplessness may thus create a psychologic barrier to taking action necessary to prevent COPD exacerbations. For example, research suggests that pulmonary rehabilitation helps to prevent or at least ameliorate COPD exacerbations.36-38 However, pulmonary rehabilitation requires patients to incorporate a complex array of behavior changes, involving regular aerobic and peripheral muscle exercise training, breathing retraining methods, compliance with medications and oxygen, tobacco cessation, and the incorporation of psychosocial counseling into daily living.5,39 Commitment to these interventions could be attenuated by feelings of helplessness. Indeed, prior research has suggested that the self-perception of control is an important factor in the outcomes of pulmonary rehabilitation because of its influence in patients’ motivation during the program.40-42 Helplessness may also amplify perceived disease severity, thereby contributing to patients’ belief that their COPD prevents them from complying with exercise regimens prescribed during rehabilitation.

Our finding that the CHI is prospectively associated with COPD-related emergency health-care uses suggests that helplessness may contribute to exacerbations and other adverse COPD events. In prospective analyses, we have presented results both with and without adjustment for the BODE Index because we acknowledge that, to at least some extent, higher COPD severity may be causing both higher degrees of helplessness and worse COPD outcomes independently. However, it is also likely that helplessness itself is contributing to higher COPD severity as measured by the BODE Index, and to this extent, “adjusting” for the BODE Index in predictive models would be inappropriate. For example, helplessness could be influencing patient motivation during exercise (and thus the 6-min walk test component of BODE) and the perception of dyspnea intensity (and thus the dyspnea component of BODE). Indeed, research in the chronic pain field has indicated that helplessness is likely to influence pain intensity.43 Thus, the causal pathway between helplessness and COPD severity may be bidirectional, with each influencing the other.

It is noteworthy that even after controlling for the BODE Index, helplessness was prospectively associated with emergency health-care use in subjects with milder COPD, but not among those with more severe COPD. This suggests that the effect of helplessness on self-management skills may be more important among subjects with less severe COPD, perhaps because improved self-management may not prevent COPD exacerbations above a certain threshold of severity. Alternatively, helplessness itself may no longer affect emergency use once patients’ COPD has progressed to more advanced stages. In either scenario, this finding is consistent with prior studies suggesting that pulmonary rehabilitation programs may be more effective in patients with less advanced COPD.44,45

Future research using the CHI may help to explain why some patients do more poorly than others in the self-management of their COPD. The CHI could be used in investigational settings, for example, to evaluate educational and psychosocial support programs for pulmonary rehabilitation or clinical visits. We hypothesize that patients may respond differently to particular interventions intended to improve self-management skills depending on their level of helplessness. Potentially, future research may help to develop pulmonary rehabilitation interventions that are tailored to patients based on their level of helplessness or are designed to specifically target helplessness in COPD.

Several study limitations must be considered. First, because an important focus in the prospective follow-up of our cohort will be studying the long-term prevention of COPD-associated morbidities, we intentionally sampled younger adults with COPD (aged 40-65 years). The age selection criteria may thus limit generalizability of some of our findings to older adults. However, we did find a strong and consistent association of the CHI with COPD severity and psychosocial factors, even after adjusting for age and other sociodemographic characteristics. Second, KP members, because they have health-care access, may also be different than the general population of adults with COPD. Mitigating this limitation, the sociodemographic characteristics of Northern California KP members are generally similar to those of the regional population.46,47 Third, selection bias could have been introduced by nonparticipation in the study. There were some modest differences among subjects who did and did not participate in the interviews and clinic visits, and this may have affected the generalizability of our results (see the online supplement). Fourth, we have not thus far assessed reproducibility of the CHI insofar as the results reported above reflect a single administration of the questionnaire to research subjects. Prospective follow-up of the described cohort will include readministration of the CHI. Finally, although our model is based upon the theory of learned helplessness and the questions in the CHI all focus on breathing problems, our study does not demonstrate that helplessness has indeed been learned secondary to COPD. In fact, helplessness may even have preceded the development of COPD. Just as the causal pathway between helplessness and COPD severity may be bidirectional, the pathway between helplessness and the development of COPD itself may even be bidirectional.

In conclusion, helplessness in COPD appears to be linked to important outcomes, including HRQL and health services use. Our study provides evidence for the internal consistency and construct validity of the CHI, a brief measure that can readily be applied in clinical investigations and, with further research, has the potential to be applied in clinical practice. Consistent with our theoretical model that helplessness may be associated with worse self-management skills, the CHI is predictive of COPD-related emergency health-care use, our measure of COPD exacerbations. Future research using the CHI should include further validation of this measure as well as an investigation into whether it helps to develop more effective interventions targeting improved patient self-management skills.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Omachi: contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis.

Dr Katz: contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis.

Dr Yelin: contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr Iribarren: contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr Knight: contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr Blanc: contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis.

Dr Eisner: contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Other contributions: This study was conducted at the University of California, San Francisco and the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research.

Abbreviations

- AQ20-R

Airways Questionnaire 20, Revised

- BODE

Body-Mass, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise

- CHI

COPD Helplessness Index

- HR

hazard ratio

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition

- KP

Kaiser Permanente

Footnotes

Funding: Dr Omachi was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [F32HS017664]. Dr Eisner was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health [R01HL077618] and the UCSF Bland Lane FAMRI Center of Excellence on Secondhand Smoke CoE2007.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):2011–2030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viegi G, Pistelli F, Sherrill DL, Maio S, Baldacci S, Carrozzi L. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):993–1013. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00082507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease axis of the Respiratory Network Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(5):585–591. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourbeau J, Nault D, Dang-Tan T. Self-management and behaviour modification in COPD. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):271–277. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Myers R, Prewitt LM. Maintenance after pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic lung disease: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(6):880–888. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-318OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowson CA, Town GI, Frampton C, Mulder RT. Psychopathology and illness beliefs influence COPD self-management. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(3):333–340. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson C. Learned helplessness and health psychology. Health Psychol. 1982;1(2):153–168. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein MJ, Wallston KA, Nicassio PM, Castner NM. Correlates of a clinical classification schema for the arthritis helplessness subscale. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(7):876–881. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicassio PM, Wallston KA, Callahan LF, Herbert M, Pincus T. The measurement of helplessness in rheumatoid arthritis. The development of the arthritis helplessness index. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(3):462–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shnek ZM, Foley FW, LaRocca NG, et al. Helplessness, self-efficacy, cognitive distortions, and depression in multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(3):287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02892293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-Effiacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wigal JK, Creer TL, Kotses H. The COPD self-efficacy scale. Chest. 1991;99(5):1193–1196. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A, Wood R. Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(5):805–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerant A, Moore M, Lorig K, Franks P. Perceived control moderated the self-efficacy-enhancing effects of a chronic illness self-management intervention. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(3):173–182. doi: 10.1177/1742395308089057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seligman ME. Learned helplessness. Annu Rev Med. 1972;23:407–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WR, Seligman ME. Depression and learned helplessness in man. J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84(3):228–238. doi: 10.1037/h0076720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Yelin EH, et al. Pulmonary function and the risk of functional limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1090–1101. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. GOLD Scientific Committee Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(5):1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality. Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Chest. 2005;128(4):2068–2075. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, Eisner MD, Katz PP, Yelin EH, Blanc PD. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in obstructive airway disease: validation of a modified version of the airways questionnaire 20. Chest. 2006;129(6):1644–1652. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Jones PW, et al. A novel, short, and simple questionnaire to measure health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(6):1874–1878. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9807097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alemayehu B, Aubert RE, Feifer RA, Paul LD. Comparative analysis of two quality-of-life instruments for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health. 2002;5(5):437–442. doi: 10.1046/J.1524-4733.2002.55151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rule BG, Harvey HZ, Dobbs AR. Reliability of the Geriatric Depression Scale for younger adults. Clin Gerentol. 1989;9(2):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancuso CA, Peterson MG, Charlson ME. Effects of depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in asthma patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(5):301–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.07006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferraro FR, Chelminski I. Preliminary normative data on the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-SF) in a young adult sample. J Clin Psychol. 1996;52(4):443–447. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199607)52:4<443::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:540–544. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(10):1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;41:46s–53s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00078002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan VS, Ramsey SD, Make BJ, Martinez FJ. Physiologic variables and functional status independently predict COPD hospitalizations and emergency department visits in patients with severe COPD. COPD. 2007;4(1):29–39. doi: 10.1080/15412550601169430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Mortality after an emergency department visit for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2006;3(2):75–81. doi: 10.1080/15412550600651271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, et al. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9201):362–368. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calverley PM. Reducing the frequency and severity of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1(2):121–124. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–778. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young P, Dewse M, Fergusson W, Kolbe J. Respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: predictors of nonadherence. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):855–859. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d27.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold R, Ranchor AV, Koëter GH, et al. Changes in personal control as a predictor of quality of life after pulmonary rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Büchi S, Villiger B, Sensky T, Schwarz F, Wolf C, Buddeberg C. Psychosocial predictors of long-term success of in-patient pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(6):1272–1277. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10061272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCathie HC, Spence SH, Tate RL. Adjustment to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the importance of psychological factors. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(1):47–53. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00240702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samwel HJ, Evers AW, Crul BJ, Kraaimaat FW. The role of helplessness, fear of pain, and passive pain-coping in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(3):245–251. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000173019.72365.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wedzicha JA, Bestall JC, Garrod R, Garnham R, Paul EA, Jones PW. Randomized controlled trial of pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, stratified with the MRC dyspnoea scale. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(2):363–369. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White RJ, Rudkin ST, Harrison ST, Day KL, Harvey IM. Pulmonary rehabilitation compared with brief advice given for severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2002;22(5):338–344. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2519–2527. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.