Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the READER model for critical reading by comparing it with a free appraisal, and to explore what factors influence different components of the model.

Design: A randomised controlled trial in which two groups of general practitioners assessed three papers from the general practice section of the BMJ.

Setting: Northern Ireland.

Subjects: 243 general practitioners.

Main outcome measures: Scores given using the READER model (Relevance, Education, Applicability, Discrimination, overall Evaluation) and scores given using a free appraisal for scientific quality and an overall total.

Results: The hierarchical order for the three papers was different for the two groups, according to the total scores. Participants using the READER method (intervention group) gave a significantly lower total score (P⩽0.01) and a lower score for the scientific quality (P⩽0.0001) for all three papers. Overall more than one in five (22%), and more men than women, read more than 5 articles a month (P⩽0.05). Those who were trainers tended to read more articles (P⩽0.05), and no trainers admitted to reading none. Overall, 58% (135/234) (68% (76/112) of the intervention group) believed that taking part in the exercise would encourage them to be more critical of published articles in the future (P⩽0.01).

Conclusion: Participants using the READER model gave a consistently lower overall score and applied a more appropriate appraisal to the methodology of the studies. The method was both accurate and repeatable. No intrinsic factors influenced the scores, so the model is appropriate for use by all general practitioners regardless of their seniority, location, teaching or training experience, and the number of articles they read regularly.

Key messages

The READER method of critical appraisal is simple and easy to apply

The method is accurate and repeatable

General practitioners using a structured appraisal are more critical of quality

The model may be used by general practitioners with different backgrounds, seniority, and experience of teaching and training

Introduction

General practitioners need to keep up to date. Evidence based medicine is a useful concept, and we all aspire to knowledge based practice, but it is not easy to appraise and assimilate all this knowledge.1 There is a huge volume of medical literature, and medical knowledge is increasing at great speed.2 We may aspire to practise evidence based medicine, seeking the answers to clinical questions in the literature and managing patients accordingly.3 But how do we assess the quality of the evidence if we have little training in clinical epidemiology and the skills of critical reading? Journal clubs may be of value and have been shown to work for those in training grades,4 but they require protected time. Texts and guidelines on critical reading are available but are increasingly complex and often demand a basic expertise. Moreover, little evidence exists that these methods have been assessed or subjected to clinical trial themselves.

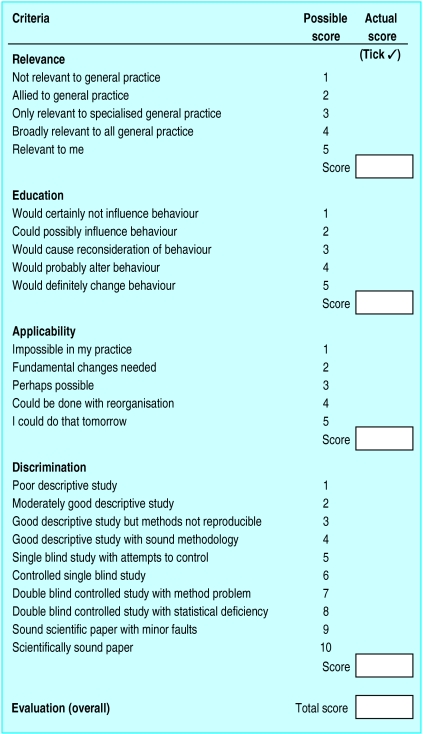

We aimed to evaluate the READER model for critical reading and determine what factors influence the five components of the model (Relevance, Education, Applicability, Discrimination, overall Evaluation) (figure).5 Our prior hypothesis was that the READER method improves a general practitioner’s ability to appraise the literature critically. We analysed the scores given by general practice principals in a randomised controlled trial of critical appraisal of three scientific papers.

Method

We invited all (n=1015) general practice principals on the medical list in Northern Ireland to participate in a study of three short papers published in the BMJ. Our only incentive was an offer to include all participants in a draw in which the prize was a voucher for a meal for two. We randomly assigned volunteers to two groups by using computerised random number allocation and sent both groups the same three papers selected from the BMJ in 1995.6–8 These papers were selected from the general practice section of the journal and related to aspects of clinical care that would be of everyday importance in general practice. Each paper was less than one page long. We also requested some personal and practice details which could be possible confounding factors. For one group we included a copy of the READER scoring method and asked if they would rate the papers by using this method (intervention group). We asked the other group (control group) to give a free appraisal of the papers on the basis of “their importance to me in everyday work.” They were asked to give two scores, one for scientific quality (maximum score of 10) and a total score (for overall importance (maximum 25)). There are no other known validated scoring methods for critical appraisal, and this free appraisal was an attempt to quantify the overall impression of the control group’s opinion. As an incentive to complete the study we again offered to enter participants’ names in a draw with a similar prize. Before we began the study we undertook a pilot study of 16 general practitioners. This revealed some minor problems in the instructions to participants and in the wording of the questionnaire. The results of this pilot study enabled us to estimate the sample size required to establish significant differences in the scores. The general practitioners who took part in the pilot were excluded from the main study. After the study we invited a sample of those in the intervention group to repeat their appraisal as a validation exercise. We also sought an objective expert opinion on the methodology scores: we asked an independent epidemiologist with experience in critical appraisal to assign a score to the methodology used in the three papers.

Differences between the two groups were compared by using the Mann-Whitney U test, and between the three groups (the intervention, control, and expert groups) by using Kruskal-Wallis one way analysis of variance on SPSS for Windows. Logistic regression was used to examine the possible associated factors for each component of the score. The Wilcoxon matched pairs, signed ranks test and McNemar’s test were used in the repeatability study.

Results

Of the 1015 principals invited to join the study, we excluded the 16 who had taken part in the pilot study. Of the 999 remaining general practitioners, 343 agreed to take part and were randomised. In all, 118 (69%) general practitioners in the intervention group and 125 (73%) in the control group completed the study (table 1). The only significant difference between the groups was in their sex, with significantly more women in the intervention group (P⩽0.01), although this was a feature of the sampling and did not reflect a differential response. The groups were similar in composition in respect of educational factors (whether they were general practice trainers, whether the practice was a training practice, whether they taught medical students regularly); length of time in practice; location of the practice; and number of partners. Both groups read a similar number of articles from academic journals each month.

Table 1.

Number (percentage of participants) in each group by sex

| Sex | Agreed to take part

|

Completed study

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | Intervention group | Control group | ||

| Male | 121 (70) | 140 (82) | 85 (72) | 107 (86) | |

| Female | 51 (30) | 31 (18) | 33 (28) | 18 (14) | |

| Total | 172 | 171 | 118 | 125 | |

In an average month, 22% of participants read more than five articles, while 11% read no articles (table 2). Significantly more men than women read more than five articles a month, but significantly more men also read no articles (P⩽0.05). Trainers were more likely to read more articles (P⩽0.05), and no trainers admitted to reading none. No relation existed between the number of articles read each month and the location of practice, the number of partners, or whether the practice was a training or teaching practice.

Table 2.

Responses by participants agreeing to take part in trial in answer to the question, “How many articles from academic journals (eg, BMJ, Br J Gen Pract etc) would you usually read fully each month?” Values are numbers (percentages) of participants

| No of articles | Intervention group (n=172) | Control group (n=171) | Total (n=343) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 11 (10) | 15 (12) | 26 (11) |

| 1-5 | 82 (72) | 78 (63) | 160 (67) |

| >5 | 21 (18) | 31 (25) | 52 (22) |

| Total | 114 (48) | 124 (52) | 238 |

The hierarchical order for the 3 papers was different for the two groups, according to the total scores (tables 3 and 4). Both groups gave the lowest score to paper 1. The highest median score in the intervention group was for paper 2; the control group ranked papers 2 and 3 equally, although it gave paper 3 a higher score for scientific quality. The control group gave a significantly higher total score than did the intervention group for paper 1 (P⩽0.01) and for papers 2 and 3 (P⩽0.001). The control group also gave a significantly higher score (P⩽0.0001) for the scientific quality of all three papers than the intervention group did for the “discrimination” component of the READER method. Our independent expert gave a discrimination score of 4 for paper 3 and a score of 2 for papers 1 and 2. The proportion whose scores agreed with the expert appraisal is shown in table 5.

Table 3.

Distribution of mean (median) scores for 18 participants in intervention group (who used READER method)

| Relevance | Education | Applicability | Discrimination | Evaluation (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper 1 | 3.8 (4) | 2.2 (2) | 3.2 (3) | 2.9 (2) | 12.1 (12) |

| Paper 2 | 4.1 (4) | 3.2 (3) | 3.5 (4) | 4.3 (4) | 15.0 (15) |

| Paper 3 | 4.0 (4) | 3.0 (3) | 2.9 (3) | 4.4 (4) | 14.1 (14) |

Papers 1, 2, and 3 are references 6, 7, and 8.

Two participants did not appraise paper 3.

See the figure for the scoring system for the READER method.

Table 4.

Distribution of mean (median) scores for 125 in control group (who used free appraisal)

| Scientific quality | Total score | |

|---|---|---|

| paper 1 | 4.5 (5) | 13.4 (15) |

| paper 2 | 6.0 (6) | 16.5 (18) |

| paper 3 | 6.7 (7) | 17.9 (18) |

Papers 1, 2, and 3 are references 6, 7, and 8.

No paper was appraised by all participants: paper 1, 121; paper 2, 122; paper 3, 122.

Maximum scores possible: 10 for scientific quality; 25 as a total.

Table 5.

Number (percentage) of participants in intervention group who agreed with independent expert

| Paper | Agreed exactly | Agreed to within 1 point in score |

|---|---|---|

| Paper 1 | 49 (42) | 81 (69) |

| Paper 2 | 23 (20) | 38 (32) |

| Paper 3 | 60 (52) | 72 (62) |

Papers 1, 2, and 3 are references 6, 7, and 8.

Of the 40 randomly selected participants in the intervention group who were invited to undertake the repeatability study, 19 replied. When the Wilcoxon matched pairs, signed ranks test was applied to the 15 variables (relevance, education, applicability, discrimination, overall evaluation, and total for each of the three papers), only two showed a significant difference between the two assessments. When we aggregated the scores given to each variable into two groups (low and high) we found no significant difference in the scores (McNemar’s test).

Almost all participants (215/232) enjoyed taking part in the exercise. Overall, 135 participants (76/112 (68%) in the intervention group and 59/122 (49%) in the control group; (P⩽0.0l)) believed that taking part in the exercise would encourage them to be more critical of published articles in the future.

Discussion

This was a very large study of critical reading, with 243 doctors completing the study. The participation rate was remarkable in view of the work required and the increasing difficulties in getting general practitioners to respond to surveys.9 Journal clubs usually appraise two papers in about one hour,10 so participating doctors had made a major commitment to our work. In previous, smaller studies,11,12 it took about 30-40 minutes to apply the READER method in a workshop, so each of the participating general practitioners probably spent about two hours reading and completing the paperwork associated with this study.

Confounding

There are possible confounding factors. In theory, critical reading is an objective skill and should not be influenced by the type of practice or seniority. The skills learned in an academic environment, however, may equip doctors to apply the skills of critical reading more effectively. None the less, the groups were similar in educational variables, type of practice, and seniority. There were significantly more women in the intervention group (the group who were asked to use the READER method), and this might be a confounding factor; there might also have been a selection bias if only the general practitioners who had an interest in critical reading took part.

Reading habits

In all, 89% of participants read at least one medical research article per month. There are no comparative data for other branches of the profession, but clearly general practitioners in this study have an interest in keeping up to date with the literature. One can draw few conclusions about the 11% who read fewer than one article each month: they may read professional journals or attend regular medical educational meetings. Indeed, while doctors report that they get most of their information from the literature, they regularly use other written sources and consult colleagues.13 All general practitioners were equally interested in reading, and it was unimportant if one was based in a teaching or training practice. All trainers read at least one research article a month, but this educational commitment does not seem to be shared by their practice partners who are not trainers.

There was a highly significant difference between the scores achieved with the READER method and those with the free appraisal. Clearly, doctors who applied a structured method of appraisal were more critical of quality. In particular, there was a highly significant difference between the score for scientific quality given by the control group and the score for discrimination given by the intervention group, and those in the intervention group gave a lower score to the methodology of the studies. Those in the intervention group were broadly in agreement with the expert opinion in their score for discrimination for papers 1 and 3, but less so for paper 2.

Others factors

Other factors may influence the scores that general practitioners give to the components of the READER model. In examining the relation between all recorded factors (whether the doctors were trainers; whether their practice was a training practice or a teaching practice for medical students; the length of time in practice; the location of the practice; the number of partners; the number of articles read each month) and the four main components of the READER method, we found that in all three papers there were only two factors that approached a significance level of P⩽0.01. These were detected in the assessment of paper 1, which focused on the use of lists by patients; the general practitioners who taught medical students were less likely than other doctors to give a high score for “relevance,” whereas general practitioners in a training practice were more likely than other doctors to give a high score to this factor. As we explored such a large number of possible relations, these findings may have occurred by chance. No consistent factors, therefore, relating to the characteristics of the participants influenced the outcome of the results of the appraisal. The repeatability study also strongly supports the reliability of the method. This is important in establishing the validity of the model.

Interest in critical appraisal methods is increasing in primary care, and like other interventions, these should be subject to clinical trial. Although several descriptions of methods of critical reading have been published, no other methods seem to have been subjected to objective evaluation. Some work shows that teaching critical appraisal can improve skills. Kitchens and Pfeifer published a controlled trial of teaching critical appraisal to residents and showed significant improvements in knowledge4; in a similar study among medical students, knowledge could similarly be improved.14 However, no published work shows that any method of critical reading can change the outcome in evaluation of the literature. We used the highest quality research methodology (a randomised controlled trial), and our study was based on a large number of ordinary general practitioners.

Conclusion

There was a significant difference between the scores given with the READER method and those given with free appraisal: general practitioners using the READER model gave a consistently lower total score and a more appropriate score to the methodology. The READER method was both accurate and repeatable. Overall, the articles scored highly on relevance but moderately on education and applicability.

No intrinsic factors influenced the scores, so the model may be used by general practitioners regardless of their seniority, location, teaching or training experience, and the number of articles they read regularly. The outcome is important as it may help to demystify the science of critical appraisal for doctors.

Figure.

Components and scoring system in READER method of critical appraisal

Acknowledgments

The BMJ offered goodwill and permission to undertake the study.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Health and Social Services (Northern Ireland).

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ. 1996;313:1062–1068. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt J. Uses and sources of medical knowledge. Lancet. 1991;338:1368–1372. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92245-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh T. Is my practice evidence based? BMJ. 1996;313:957–958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7063.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitchens JM, Pfeifer MP. Teaching residents to read the medical literature: a controlled trial of a curriculum in critical appraisal/clinical epidemiology. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:384–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02599686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacAuley D. READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:83–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Middleton JF. Asking patients to write lists: feasibility study. BMJ. 1995;311:34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien J, Long H. Urinary incontinence: long term effectiveness of nursing intervention in primary care. BMJ. 1995;311:1208. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7014.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watura R, Lloyd DCF, Chawda S. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee: direct access for general practitioners. BMJ. 1995;311:1614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7020.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAvoy BR, Kaner EFS. General practice postal surveys: a questionnaire too far? BMJ. 1996;313:732–733. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siderov J. How are internal medicine residency journal clubs organised, and what makes them successful? Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1193–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacAuley D, Sweeney KS. A new model for critical reading. Forum 1994;10(8):52-4.

- 12.MacAuley D. Critical reading using the READER acronym at an international workshop. Fam Pract. 1996;13:104–105. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:596–599. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett KJ, Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Neufield VR, Tugwell P, Roberts R. A controlled trial of teaching critical appraisal of the clinical literature to medical students. JAMA. 1987;257:2451–2454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]