Abstract

It has been suggested that cGMP kinase I (cGKI) dampens cardiac hypertrophy. We have compared the effect of isoproterenol (ISO) and transverse aortic constriction (TAC) on hypertrophy in WT [control (CTR)] mice, total cGKI-KO mice, and cGKIβ rescue mice (βRM) lacking cGKI specifically in cardiomyocytes (CMs). Infusion of ISO did not change the expression of cGKI in the hearts of CTR mice or βRM but raised the heart weight by ∼20% in both. An identical hypertrophic growth response was measured in CMs from CTR mice and βRM and in isolated adult CMs cultured with or without 1 μM ISO. In both genotypes, ISO infusion induced similar changes in the expression of hypertrophy-associated cardiac genes and significant elevation of serum atrial natriuretic peptide and total cardiac cGMP. No differences in cardiac hypertrophy were obtained by 7-day ISO infusion in 4- to 6-week-old conventional cGKI-KO and CTR mice. Furthermore, TAC-induced hypertrophy of CTR mice and βRM was not different and did not result in changes of the cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase activities in hypertropic hearts or CMs. These results strongly suggest that cardiac myocyte cGKI does not affect the development of heart hypertrophy induced by pressure overload or chronic ISO infusion.

Keywords: cyclic nucleotides, phosphodiesterase, phosphorylation, transverse aortic constriction, sildenafil

Clinical studies and genetically modified mice have supported the notion that natriuretic peptides (NPs), the particulate guanylyl cyclase (GC)-A, and the second messenger cGMP can attenuate the development of pressure- or volume-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis (1). Disruption of the murine GC-A gene, the receptor for the cardiac “hormones” atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), results in salt-resistant elevation of blood pressure, cardiac fibrosis, and hypertrophy (2, 3). To a great extent, hypertrophy is independent of blood pressure elevation (4, 5) but is enhanced transverse aortic constriction (TAC) in the absence of GC-A (4). Further studies using cardiac muscle-specific deletion of GC-A confirmed that cardiac muscle hypertrophy is independent of changes in blood pressure (6). ANP, nitric oxide (NO) donors, and 8-Br-cGMP inhibited norepinephrine-induced hypertrophy of cardiac cells and fibroblasts (7, 8).

Although it is recognized that GC-A-deficient hearts exhibit marked hypertrophy with interstitial fibrosis (2, 9), deletion of ANP did not result in obvious hypertrophy and fibrosis (10). Other reports have indicated that ANP ablation in mice causes an accelerated susceptibility to hypertrophy induced by different stress stimuli (11, 12). Obviously, ANP and BNP secreted by the cardiomyocytes (CMs) act as paracrine factors that exert antifibrotic effects in vivo and play a role as local regulators of ventricular remodeling. Furthermore, it has been shown that rats expressing a dominant-negative mutant of GC-B and having an attenuated cGMP response to C-natriuretic peptide and a normal response to ANP showed marked cardiac hypertrophy (13). More recent results (13–15) suggest that hypertrophy could be associated with fibroblast “dysfunction” (16).

These studies support the hypothesis that the antihypertrophic and antifibrotic effects of ANP and BNP are mediated by cGMP, probably at least in part by direct effects on the CM. However, the signaling pathway downstream of cGMP is much less clear than that leading to increased cGMP levels. It has been largely assumed that cGMP activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (cGKI) mediates most of or all the effects of cGMP in the cardiac myocyte (17–22). However, cardiac myocytes are reported to contain several cGMP hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases (PDEs) (23, 24), including PDE-1s (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent), PDE-2 (cGMP-stimulated), and PDE-5 (cGMP-specific). Because several of these PDEs are also targets of cGMP, it is possible that cGMP may affect cardiac hypertrophy indirectly through modulation of the activity of these PDEs (24), which regulate cAMP levels and, thereby, associated aspects of cardiac contractility. For example, protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent modulation of the L-type calcium channel, cardiac ryanodine receptor, sarcoplasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) (25–28), and calcium has been implicated in cardiac hypertrophy induced by the stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) (29–31).

Similarly, the cGMP hydrolyzing PDE-5 has been implicated in the regulation of adrenergic-stimulated cardiac contractility by NOS 3-dependent signaling (32, 33) and in murine cardiac hypertrophy induced by TAC (33, 34). A growing body of evidence indicates that both hypertrophy and chamber remodeling were inhibited by sildenafil (SIL) treatment in mice subjected to TAC (35), presumably through activation of cGKI. However, it has also been reported that α-myosin heavy chain promoter-driven overexpression of the cGKI enzyme had no effects on several cardiac parameters, including weight and structure (36). Furthermore, recoupling of NOS in cardiac hypertrophy was effective to protect the heart from failing, but this was independent of cGKI activity and related to reduced oxidant stress (37).

In contrast to these experiments carried out with adult tissues or animals, studies with cultured neonatal CMs that express high levels of cGKI (17) showed that cGKI mediated the antihypertrophic effects of NO (38). cGKI inhibited the calcineurin-nuclear factor of activated T cells hypertrophy signaling pathway (20), most likely by decreasing the activity of L-type calcium channels (36, 39). Alternative pathways for the protection of the heart that have been reported include inhibition of the myocardial Na+/H+ exchanger (40), transmission of cardioprotective signals from the cytosol to mitochondria (21), decreased apoptosis in the presence of enhanced nuclear accumulation of zyxin and Akt (41), reduced cardiomyofibrillar stiffness by titin phosphorylation (42), and decreased apoptosis by interference with the TAB1-p38 mitogen-activated PK pathway (19). At present, it is unclear which, if any, of these diverse mechanisms are involved in the antihypertrophic effect of cGMP in the intact animal. Alternatively, it is also possible that at least part of the antihypertrophic effects of cGMP is mediated independent of CM cGKI, presumably by effectors secreted by myofibroblasts in response to, for example, BNP.

To determine the significance of cGKI signaling in cardiac hypertrophy in the intact animal, we used mice that express cGKIβ only in smooth muscle (SM) cells [cGKIβ rescue mice (βRM)] (43) but not in CMs. Analysis of these animals shows that loss of cGKI in CMs does not potentiate hypertrophy induced by isoproterenol (ISO) or TAC, nor does it increase the basal size of the heart or change the activity of cGMP-hydrolyzing PDEs.

Results

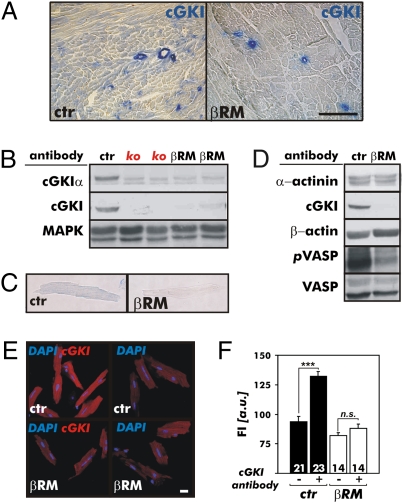

cGKI has been implicated particularly in cultured cells as a cardiac factor that reduces hypertrophy to various stimuli (44, 45). To test this hypothesis in the intact animal, we used three different models: WT control (CTR) mice; conventional cGKI-KO mice that do not express the cGKI isozymes in any tissue (46); and mice that express the cGKIβ isozyme under the control of the endogenous SM22α promoter in all SMs, including the vasculature of the heart on a cGKI-negative background (βRM) (43). In agreement with the hypothesis, cGKIα is expressed in ventricles of CTR mice but is not detectable in the cardiac muscle of βRM (Fig. 1 A and B). These findings obtained with immunocytochemical and Western blot analysis were extended to isolated CMs using specific antibodies (47). cGKI was detectable in isolated CTR but not in βRM cardiac myocytes (Fig. 1 C–F), strongly supporting the notion that βRM lack the cGKI protein in CMs. Although the cGKI protein was not detected in CMs by several immunological procedures, it was possible that low concentrations of the enzyme were present and functional. Therefore, we tested the phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), a well-characterized substrate for cGKI (48). Activation of cGKI increased the phosphorylation of Ser-239, the cGKI target site of VASP (48), strongly in CTR but not in βRM hearts (Fig. 1D) demonstrating the functional absence of myocardial cGKI. Because the Iβ isoform of cGKI is present in SMs (Fig. 1A), the minor phospho-VASP239 signal detectable in βRM hearts most likely resulted from expression in the vasculature.

Fig. 1.

Expression analysis and activity of the cGKI in hearts of CTR mice and βRM. (A) By immunohistochemistry, cGKI was detected in the vasculature and myocardium of cardiac sections from adult CTR (ctr) mice but was absent from the heart muscle of βRM. In these animals, cGKI protein expression was limited to the SM layer of coronary vessels as expected by the endogenous SM22α gene promoter-driven expression of the cGKI construct. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B) Western blot analysis of ventricular protein lysates using polyclonal antibodies that specifically detect either the cGKIα isoform or all cGKI isoforms. The cardiac cGKIα isoform was present in heart lysates of the ctr mice but was not detected in hearts of conventional cGKI-KO (ko) mice or βRM. By identifying MAPK, equal loading of the gel is demonstrated. (C) Heart homogenates of ctr mice and βRM were subjected to immunoblotting analysis to show the strongly reduced cGKI-dependent phosphorylation of cardiac target proteins. The antibodies used to detect cGKI substrate phosphorylation were specific for the phospho-Ser239 residue of the phospho-VASP239 (pVASP). α-Actinin and VASP common antibodies were used as loading controls. cGKI immunohistochemistry (D) and immunofluorescence (E) of adult cardiac myocytes. The cGKI protein was only detectable in control cells but was not present in CMs of βRM. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (F) Quantification of cGKI fluorescence intensity (FI) of adult ctr mice (black bars) and βRM (white bars) CMs. FI was determined using the specific cGKI antibodies and fluorophore-coupled secondary antibodies to detect the primary antibody protein complexes (***P < 0.001). a.u., arbitrary units; n.s., not significant.

We next tested whether or not the gene-targeted animals responded normally to a single injection of 0.1 mg/kg of ISO (Fig. S1). The basic cardiac response to ISO in βRM was without any pathological findings. The βRM had a normal cardiac electrocardiogram at rest and in the presence of ISO (Fig. S1A). ISO increased heart rate (Fig. S1B) and fractional shortening (Fig. S1 C and D) to the same extent in CTR mice and βRM. Exposure of isolated adult CMs for 24 h to 1 μM ISO increased the cell size by 7.3% and 7.9% in CTR mice and βRM, respectively (Fig. S2 A and B). The hypertrophic response of CMs was extended by analyzing the gene expression of SERCA. A similar level of down-regulation was detected in the CMs of both genotypes treated with ISO (Fig. S2C). These results are consistent with previous reports supporting the notion that CM cGKIα is dispensable for the basic β-AR regulation of the heart (29, 30, 38, 49, 50).

In the next series of experiments, 10–14-week-old littermates of either genotype were stimulated by ISO infused at a constant rate of 30 mg/kg per day for 7 days using an osmotic minipump. Heart rate was recorded continuously by telemetry and was used as an indirect measure for the amount of ISO delivered to individual animals. Heart rate increased in all mice treated with ISO infusion to the same extent. No difference was noted in the average heart rates during either the day or night in both the CTR and +ISO groups (Fig. S3).

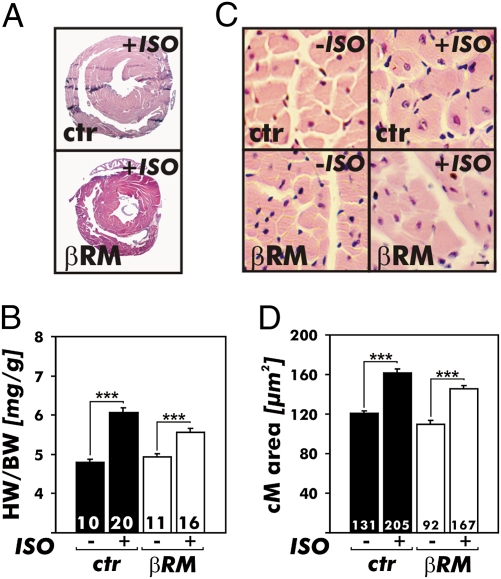

ISO infusion increased the heart weights (HWs) to the same extent, 19.7% and 19.6% in CTR mice and βRM, respectively (Fig. 2). If cGKI activity was required as a normal brake on regulation of HW under “basal” cGMP conditions, lack of cGKI should give larger hearts. Nevertheless, calculation of the HW per body weight (BW) confirmed that ISO infusion did not augment the cardiac weight of βRM (CTR mice, +26.5%; βRM, +12.7%) (Fig. 2B). As another measure of hypertrophy, in situ morphometric analysis of left ventricular myocyte size (Fig. 2 C and D) revealed that ISO infusion raised the myocyte size to 133.6% and 132.6% as compared with the saline-treated groups in CTR mice and βRM, respectively. Cardiac fibrosis also was equally accelerated in animals subjected to chronic ISO treatment, with no differences seen between the two genotypes.

Fig. 2.

Heart growth induced by ISO infusion for 7 days via implanted miniosmotic pumps in CTR mice and βRM. (A) Representative H&E-stained cardiac cross-sections of ISO-treated animals. Note that the hearts of βRM appear smaller because the animals weigh less [26.4 vs. 23.1 g for CTR (ctr) mice (n = 20) and βRM (n = 16), respectively]. (B) Chronic ISO infusion caused hypertrophy of the heart as indicated by increases of the HW/BW ratios. The hypertrophy response was similar in each genotype (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (C and D) Cross-sectional areas of cardiac myocytes. (C) H&E staining of heart sections from ctr mice and βRM at baseline (Left, −ISO) and after chronic ISO infusion (Right, +ISO). (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (D) Summary of cell size quantified by morphometry. ISO treatment provoked a significant increase in the CM (cM) cross-sectional areas in hearts of ctr mice and βRM. The areas were determined in the histological sections shown in A and as described in Materials and Methods (***P < 0.001).

Further evidence that the lack of cGKI in cardiac myocytes does not alter ISO-induced hypertrophy came from mRNA analysis of the cardiac genes associated with the hypertrophy program. Genes that are normally expressed in the adult heart were down-regulated (Fig. S4B), whereas expression of fetal genes (Fig. S4A) and fibrosis markers (Fig. S4C) was induced in the ISO groups. The mRNA levels of all markers analyzed (Fig. S4) changed in the same direction and to a similar extent in both genotypes. Importantly, no differences in the absolute expression levels of the NP receptors GC-A and GC-B were detected in CTR mice and βRM following 7 days of ISO (Fig. S5 A–D).

In line with the transcriptional analysis (Fig. S4), we noticed a significant increase of serum ANP and cardiac cGMP levels in animals that developed cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. S5 E and F).

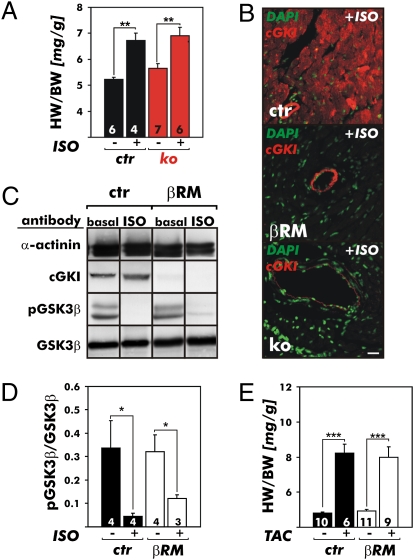

We performed two additional sets of experiments to rule out the possibility that cGKI might be reexpressed following the chronic ISO infusion in βRM CMs or that a lack of accelerated heart hypertrophy in these animals was conferred by cGKI present in the SM of these animals. At the age of 4 to 6 weeks, conventional cGKI-KO mice (43, 46) and their littermate juvenile CTRs were infused for 7 days with ISO at a rate of 30 mg/kg per day. Again, the HW/BW ratios increased in both genotypes to a similar extent in response to the hypertrophic stimulus (CTR, +28.7%; cGKI-KO, +22.3%) (Fig. 3A). Immunostaining of cardiac sections of ISO-treated mice clearly indicated that the CTR hearts expressed cGKI in myocytes, the βRM hearts expressed cGKI in vascular SM, and the cGKI-KO hearts did not express cGKI in any heart cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Cardiac hypertrophy and signaling in various gene-targeted cGKI mouse models. (A) Effects of 7 days of chronic ISO infusion via implanted miniosmotic pumps on the hearts of 4- to 6-week-old CTR (ctr) mice and littermate conventional cGKI-KO (ko) mice. Chronic ISO infusion caused hypertrophy of the heart as indicated by increases of the HW/BW ratios. The response to the hypertrophy stimulus of each genotype indicated was similar in comparison to the respective saline-infused groups (**P < 0.01). (B) cGKI expression analysis in the hearts of CTR (ctr) mice, βRM, and ko mice that were chronically treated with ISO for 7 days. DAPI (green) was used as a nuclear counterstain. The cGKI protein (red) was detected in the vasculature and myocardium of ctr mice but was absent from the hearts of ko mice. In the βRM, the cGKI expression pattern was not influenced by the hypertrophy stimulus that induced a fetal gene program (Fig. S4) but was similar to baseline conditions and yet limited to the vasculature. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) Western blot (C) and quantification (D) of GSK3β-to-phospho-GSK3β (pGSK3β) ratio of ventricular protein lysates from ctr mice and βRM at baseline and after 7 days of ISO. (E) Effect of pressure overload induced by TAC on cardiac hypertrophy. Twenty-one days of TAC caused a significant increase in the HW/BW ratios in both genotypes analyzed in A (*P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

We further analyzed the impact of myocardial cGKI on the activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) because GSK3 represents a point of convergence for several hypertrophic signals. It has been shown that dephosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 positively regulates the ability of this enzyme to antagonize ISO-induced hypertrophy in the adult heart (51), probably in a mode that depends on PDE-5 activity (34). Indeed, in the presence of cardiac cGKI, we detected a significant decrease in the phospho-GSK3β/GSK3β ratio after ISO treatment (Fig. 3 C and D). However, in the βRM hearts, the same changes were observed (Fig. 3 C and D). These results indicate that the Ser9 phosphorylation status of GSK3β is not changed by a cardiac cGKI pathway in ISO-induced hypertrophy (34).

We also considered the possibility that ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy is unique in that this type of hypertrophy might not be modulated by myocardial cGKI activity. An alternative model widely used to induce cardiac hypertrophy is TAC (32–34). Therefore, littermate CTR mice and βRM were subjected to the TAC procedure. Animals were killed after 21 days, and the HWs and BWs were determined (Fig. 3E). TAC increased the HW of both CTR mice and βRM to the same extent (CTR mice, +40.1%; βRM, +41.8%). Again, no difference was detectable between the two genotypes when the HW was normalized to BW (CTR mice, +71.0%; βRM, +62.1%). Taken together, these results suggest that the development of murine heart hypertrophy is not augmented by the absence of endogenous cGKI in cardiac myocytes.

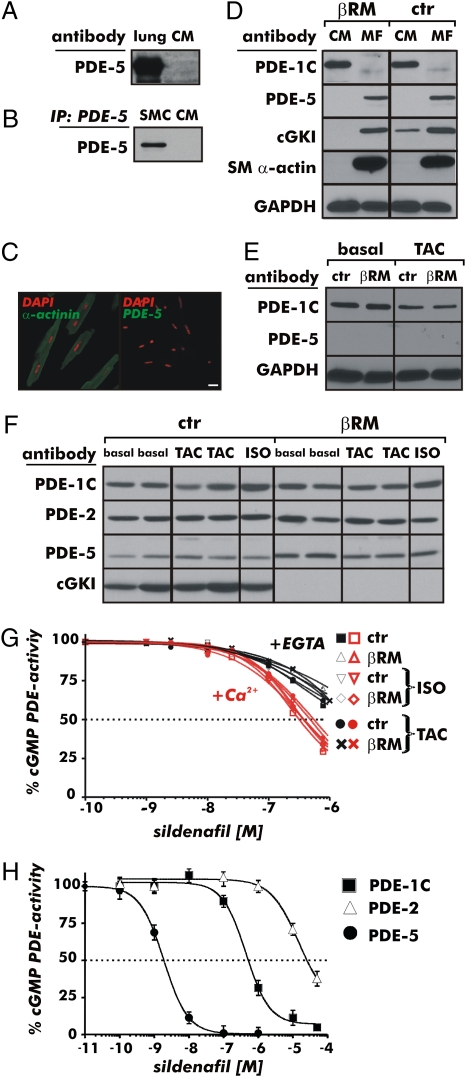

Recent evidence has suggested that the antihypertrophic effect of SIL in the heart is by means of inhibition of cardiac myocyte PDE-5 activity and subsequent activation of cGKI (33, 52). It is also known that cGKI can stabilize an activated state of PDE-5 by phosphorylating it (23). Therefore, we studied the expression of cGMP-hydrolyzing PDEs, such as PDE-1, PDE-2, and PDE-5, and the total cGMP-hydrolytic activities in the heart of CTR mice and βRM. We and others (53) have hypothesized that these PDEs might affect specific pools of cardiac cGMP, and thereby the response of the heart to hypertrophic stimuli. First, we tested the specificity of our PDE-5 antibodies by using protein extracts from lung and SM cells as positive controls (Fig. 4 A and B). We were unable to detect PDE-5 in isolated CMs by several different biochemical methods, including after TAC (Fig. 4 A–E). However, cardiac myofibroblasts that were identified by SM α-actin antibodies in vitro do contain the PDE-5 protein (Fig. 4D). Again, in adult CMs isolated from both CTR mice and βRM, no PDE-5 expression was detectable, and by 21 days of TAC, we also did not detect PDE-5 (Fig. 4E). In CTR samples of total heart homogenates, the small expression of PDE-5 is consistent with the presence of PDE-5 in blood vessels and fibroblasts (Fig. 4F and Fig. S6). PDE-1C was found to be a major cGMP-hydrolyzing PDE expressed only in CMs but not in fibroblasts (Fig. 4D). Ca2+/calmodulin-activated PDE-1C can hydrolyze both cAMP and cGMP equally well and is sensitive to SIL inhibition in the high nanomolar range (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

Expression and activity of cGMP-hydrolyzing PDEs in the hearts and isolated cardiac cells of CTR mice and βRM. The specificity of the PDE-5 antibodies used was verified by detecting the PDE-5 protein in the lung (A) and SM cells (SMCs) (B). Using the same antibodies, no PDE-5 protein was detectable in CMs. (C) In adult CMs from CTR mice, which were identified by antibodies specific for the cardiac marker protein α-actinin, PDE-5 was not detectable. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (D) Western blot analysis of adult CMs and cardiac myofibroblasts (MFs) from CTR (ctr) mice and βRM. PDE-5 was absent from CMs but was detectable in MFs. SM α-actin was used to discriminate between MFs and CMs. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent cGMP- and cAMP-hydrolyzing PDE-1C was present only in CMs. (E) Western blot analysis of adult CMs purified previous to (basal) and after 21 days of TAC. (F) Expression of PDE-1/2/5 and the cGKI protein in different models of cardiac hypertrophy. No significant changes were detectable in the heart after TAC and/or ISO treatment between ctr mice and βRM as compared with the respective basal expression. (G) SIL inhibition of cGMP-hydrolytic activity in heart lysates at basal level and after ISO treatment or TAC. The IC50 of SIL on the cGMP-hydrolyzing PDE activity was similar for both genotypes and did not change as a result of the hypertrophic stimuli. Importantly, the IC50 determined was about 450 nM, and was therefore in the range of PDE-1C inhibition. (H) cGMP-hydrolyzing activity of different recombinant PDEs in the presence of SIL (100 pM to 100 μM). The IC50s for the recombinant enzymes were 1.9 nM, 422 nM, and 15 μM for PDE-5, PDE-1C, and PDE-2, respectively.

In vivo, neither TAC nor chronic ISO treatment changed the levels of PDE-1C, PDE-2, or PDE-5 in both genotypes (Fig. 4F). A small but reproducible increase in the total PDE-5 protein content was apparent in βRM hearts, but there was no difference noticed between healthy and hypertrophic hearts. Therefore, we analyzed SIL sensitivity of the cGMP-hydrolytic activity from CTR mice and βRM, but did not detect any significant inhibition at low concentrations of SIL (10–50 nM) (Fig. 4G).

Importantly, the range of SIL concentrations that inhibited the cardiac cGMP-hydrolytic activity was similar for both genotypes and did not change with hypertrophy induced by ISO treatment or TAC. When we measured PDE activity in the presence of Ca2+/calmodulin, the inhibitory curve shifted to the left, indicating that the predominant PDE is PDE-1C (about 90% of the hydrolytic activity) under these conditions. At concentrations of SIL that are specific for the inhibition of PDE-5 (≤10 nM), we did not detect any inhibition of cGMP-hydrolytic activity. In fact, the IC50 for SIL inhibition was ≈400 nM, corresponding to the concentrations of SIL at which it inhibits PDE-1C (Fig. 4H).

Discussion

The results presented suggest the following conclusions that appear to be valid for the intact adult animal:

(i) The βRM do not express cGKI in cardiac myocytes, whereas the same cells from CTRs express cGKI.

(ii) In the intact animal, many physiological heart functions are not affected by the absence of cGKI in CMs and loss of cGKI does not influence the basic regulation of the heart by β-AR stimulation under basal conditions of cGMP.

(iii) ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy was not affected by the absence of cGKI in two different transgenic mouse lines that lacked cGKI in the heart.

(iv) The degree of cardiac hypertrophy induced by TAC was not changed in animals that lacked cGKI in cardiac myocytes.

(v) cGMP-hydrolytic activity is not affected by the absence of cGKI in CMs and does not change in response to hypertrophic growth signals to the heart.

Overall, these data suggest that ablation of cGKI in the CM does not greatly affect several different hypertrophic stimuli that lead to hypertrophy under normal developmental drive.

These conclusions appear to be in contradiction to many of those reached in several previous reports, most of which suggest that cGMP acting via cGKI in CMs attenuates cardiac hypertrophy (1–3, 5–7, 32–34, 54). How can the present results be reconciled with these previous reports? Inspection of the previous studies indicates that in most of them, cardiac growth was stimulated either by unknown hormonal factors (1–3, 5–7, 12) or by hormones such as norepinephrine (7) that are not selective for one receptor type. It therefore seems possible that cGKI affects primarily cardiac hypertrophy induced by receptors that signal through the G proteins αq and α11 (55) but is largely dispensable for factors that signal through Gαs and cAMP (29). More experiments will be needed to determine if this is true. However, even if this is true, it does not resolve the apparent discrepancy with respect to the lack of effect of cGKI ablation on TAC-induced hypertrophy, because this model is commonly thought to have a major angiotensin II component to it. Angiotensin signaling is largely via AT1 receptors, which activate Gαq/11 (33, 34, 52). However, recently, it has been reported that the cardiac AT1 receptor is not essential for the development of TAC-induced hypertrophy (56, 57), so perhaps the effects of angiotensin II are not mediated via G11.

It is also possible that the cGKI pathway is only antihypertrophic when cGMP levels are raised rather high. Many models of hypertrophy in which increased cGMP pathway components show antihypertrophic responses are best seen when there is either a high level of GC activation or PDE inhibition present. For example, when used at high nanomolar concentrations, SIL, a PDE-5 inhibitor, is reported to oppose TAC-induced hypertrophy (34). This is presumed to be attributable to increased cGMP in one or more compartments in the heart. It has been shown that these same concentrations of SIL also inhibit PDE-1C activity by ∼20% in heart extracts (58). It is also reported that SIL treatment increases cardiac cGKI activity efficiently, although it is not clear that this occurs in the CM (34). Nevertheless, taking all these observations into account, we found it very unexpected that there would be no effect of deletion of cardiac cGKI on cardiac hypertrophy, particularly because our data also show that chronic infusion of ISO significantly induced the transcript level of cardiac ANP(Fig. S4A) as well as the serum level of ANP (Fig. S5E). In addition, direct measurement of cardiac cGMP concentration showed a 3- to 4-fold increase in response to ISO (59, 60) (Fig. S5F).

Taken together, the data suggest that caution should be applied in interpreting the effects of SIL on cGKI and cGMP PDE activity in the heart. It was recently reported that PDE-5 is up-regulated in patients with end-stage heart failure; however, 2 μM SIL was used for cGMP PDE assays as a test for PDE-5 activity (54). At this concentration, SIL can inhibit most of the cardiac PDE-1C activity (Fig. 4H). Moreover, in our study, we cannot detect endogenous PDE-5 in CMs of CTR mice or βRM in isolated myocytes and we do not observe an increase in PDE-5 protein or activity during hypertrophy; furthermore, we do not find any changes in the total cGMP-hydrolytic activity in the myocardium of the two genotypes. Thus, it would seem quite possible that the antihypertrophic effects of SIL could be mediated by some enzyme other the PDE-5, perhaps PDE-1C, which is abundant in CMs. Whether or not inhibition of PDE-1C can stimulate cAMP-dependent pathways in discrete cellular compartments of the CM, and thereby influence hypertrophy, remains to be determined and likely will require either PDE-1C knockout animals or highly selective PDE-1C inhibitors. Although clearly being beyond the scope of this report, studies of an inducible CM-specific PDE-5 gene KO in the adult animal should be a valuable tool to answer what are the molecular mode(s) of action of PDE-5 inhibitors on cardiac cGMP and remodeling.

Finally, one simple straightforward explanation is that if cGKI is involved in mediating the antihypertrophic effect of cGMP in the heart, it is attributable to its expression in cell types other than the CM (14). Similarly, if the effects of SIL on cardiac hypertrophy are mediated by inhibition of PDE-5, it could also be mediated indirectly by another non-CM cell type. Cardiac fibroblasts have little or no cGKI in the βRM (Fig. 3B). However, we noticed that cGKI was easily detectable in cardiomyofibroblasts of βRM when cultured for 5 days (Fig. 4D). This was expected (61), because in the βRM, cGKIβ is under the control of the endogenous SM22α promotor, which is known to be active in fibroblast-like cells. Interestingly, we detected PDE-5 in the same cells by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4D). PDE-5 activity contributed about 50% of the total cGMP-hydrolyzing activity of myofibroblasts. However, we did not notice any changes of cGKI or PDE-5 protein levels in total hearts, suggesting that the amounts of cGKI and PDE-5 in myofibroblasts were a relatively small fraction of the total heart samples.

During the past decade, the NO/cGKI pathway has been implicated as being protective to the heart during ischemia/reperfusion (reviewed in 44, 45). A common mechanism suggested by several researchers is that NO/cGKI transmits a “protective signal” to the mitochondria (21). The mitochondrial target(s) of cGKI is unclear (45); therefore, it is still quite possible that NO effects on the mitochondria are mediated by mechanisms independent of cGKI. Considering the discrepant results presented in this report, we would like to raise the possibility that some of the antihypertrophic effects of cGMP are mediated by a target protein that is independent of cGKI.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods are described in SI Materials and Methods, including chronic ISO administration; transverse aortic constriction surgery; echocardiography; histological, immunohistochemical, and gene expression analyses; Western blot analysis; and PDE assays. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using OriginPro software, version 6.1 (OriginLab).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabine Brummer, Teodora Kennel, and Astrid Vens for expert technical assistance. We acknowledge the excellent help of Nicolas Jäger at the cardiac myocyte planimetry facility. This research was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to R.L. and F.H.), the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM083926) (to J.B.), and the Leducq Foundation (to J.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1001360107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nishikimi T, Maeda N, Matsuoka H. The role of natriuretic peptides in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliver PM, et al. Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and sudden death in mice lacking natriuretic peptide receptor A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14730–14735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez MJ, et al. Salt-resistant hypertension in mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide. Nature. 1995;378:65–68. doi: 10.1038/378065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles JW, et al. Pressure-independent enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:975–984. doi: 10.1172/JCI11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishimoto I, Rossi K, Garbers DL. A genetic model provides evidence that the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide (guanylyl cyclase-A) inhibits cardiac ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2703–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtwick R, et al. Pressure-independent cardiac hypertrophy in mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted inactivation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclase-A. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1399–1407. doi: 10.1172/JCI17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderone A, Thaik CM, Takahashi N, Chang DL, Colucci WS. Nitric oxide, atrial natriuretic peptide, and cyclic GMP inhibit the growth-promoting effects of norepinephrine in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:812–818. doi: 10.1172/JCI119883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horio T, et al. Inhibitory regulation of hypertrophy by endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide in cultured cardiac myocytes. Hypertension. 2000;35:19–24. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellmers LJ, et al. Npr1-regulated gene pathways contributing to cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38:245–257. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John SW, et al. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science. 1995;267:679–681. doi: 10.1126/science.7839143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco V, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide dose-dependently inhibits pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling. Hypertension. 2004;44:746–750. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000144801.09557.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori T, et al. Volume overload results in exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy in the atrial natriuretic peptide knockout mouse. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langenickel TH, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic rats expressing a dominant-negative mutant of the natriuretic peptide receptor B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4735–4740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510019103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li P, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits transforming growth factor beta-induced Smad signaling and myofibroblast transformation in mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res. 2008;102:185–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maki T, et al. Effect of neutral endopeptidase inhibitor on endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide as a paracrine factor in cultured cardiac fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: Therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:657–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar R, Joyner RW, Komalavilas P, Lincoln TM. Analysis of expression of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in rabbit heart cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:967–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegener JW, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase I mediates the negative inotropic effect of cGMP in the murine myocardium. Circ Res. 2002;90:18–20. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.103222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiedler B, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I inhibits TAB1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase apoptosis signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32831–32840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiedler B, et al. Inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT hypertrophy signaling by cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11363–11368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162100799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa AD, et al. Protein kinase G transmits the cardioprotective signal from cytosol to mitochondria. Circ Res. 2005;97:329–336. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000178451.08719.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ecker T, et al. Decreased cardiac concentration of cGMP kinase in hypertensive animals. An index for cardiac vascularization? Circ Res. 1989;65:1361–1369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kass DA, Champion HC, Beavo JA. Phosphodiesterase type 5: Expanding roles in cardiovascular regulation. Circ Res. 2007;101:1084–1095. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phos-phodiesterases: Essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein B, et al. Relation between contractile function and regulatory cardiac proteins in hypertrophied hearts. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H2021–H2028. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.6.H2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marks AR. Cardiac intracellular calcium release channels: Role in heart failure. Circ Res. 2000;87:8–11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziolo MT, Lewandowski SJ, Smith JM, Romano FD, Wahler GM. Inhibition of cyclic GMP hydrolysis with zaprinast reduces basal and cyclic AMP-elevated L-type calcium current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:986–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono K, Trautwein W. Potentiation by cyclic GMP of beta-adrenergic effect on Ca2+ current in guinea-pig ventricular cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1991;443:387–404. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmer HG. Catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy: Significance of proto-oncogene expression. J Mol Med. 1997;75:849–859. doi: 10.1007/s001090050176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Métrich M, et al. Epac mediates beta-adrenergic receptor-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;102:959–965. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewin G, et al. Critical role of transcription factor cyclic AMP response element modulator in beta1-adrenoceptor-mediated cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:79–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.786533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balligand JL, et al. Nitric oxide-dependent parasympathetic signaling is due to activation of constitutive endothelial (type III) nitric oxide synthase in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14582–14586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takimoto E, et al. cGMP catabolism by phosphodiesterase 5A regulates cardiac adrenergic stimulation by NOS3-dependent mechanism. Circ Res. 2005;96:100–109. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152262.22968.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takimoto E, et al. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagayama T, et al. Sildenafil stops progressive chamber, cellular, and molecular remodeling and improves calcium handling and function in hearts with pre-existing advanced hypertrophy caused by pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schröder F, et al. Single L-type Ca(2+) channel regulation by cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I in adult cardiomyocytes from PKG I transgenic mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moens AL, et al. Reversal of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis from pressure overload by tetrahydrobiopterin: Efficacy of recoupling nitric oxide synthase as a therapeutic strategy. Circulation. 2008;117:2626–2636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wollert KC, et al. Gene transfer of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I enhances the antihypertrophic effects of nitric oxide in cardiomyocytes. Hypertension. 2002;39:87–92. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Méry PF, Pavoine C, Belhassen L, Pecker F, Fischmeister R. Nitric oxide regulates cardiac Ca2+ current. Involvement of cGMP-inhibited and cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterases through guanylyl cyclase activation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26286–26295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kilic A, et al. Enhanced activity of the myocardial Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-1 contributes to cardiac remodeling in atrial natriuretic peptide receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:2307–2317. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato T, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide promotes cardiomyocyte survival by cGMP-dependent nuclear accumulation of zyxin and Akt. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2716–2730. doi: 10.1172/JCI24280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krüger M, et al. Protein kinase G modulates human myocardial passive stiffness by phosphorylation of the titin springs. Circ Res. 2009;104:87–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber S, et al. Rescue of cGMP kinase I knockout mice by smooth muscle specific expression of either isozyme. Circ Res. 2007;101:1096–1103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burley DS, Ferdinandy P, Baxter GF. Cyclic GMP and protein kinase-G in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion: Opportunities and obstacles for survival signaling. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:855–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heusch G, Boengler K, Schulz R. Cardioprotection: Nitric oxide, protein kinases, and mitochondria. Circulation. 2008;118:1915–1919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfeifer A, et al. Defective smooth muscle regulation in cGMP kinase I-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1998;17:3045–3051. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geiselhöringer A, Gaisa M, Hofmann F, Schlossmann J. Distribution of IRAG and cGKI-isoforms in murine tissues. FEBS Lett. 2004;575:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butt E, et al. cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation sites of the focal adhesion vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) in vitro and in intact human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14509–14517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iaccarino G, Dolber PC, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor kinase-1 levels in catecholamine-induced myocardial hypertrophy: Regulation by beta- but not alpha1-adrenergic stimulation. Hypertension. 1999;33:396–401. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Wiesmann F, Lohse MJ. Progressive hypertrophy and heart failure in beta1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7059–7064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antos CL, et al. Activated glycogen synthase-3 beta suppresses cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:907–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231619298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takimoto E, et al. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:408–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI35620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsai EJ, Kass DA. Cyclic GMP signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:216–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pokreisz P, et al. Ventricular phosphodiesterase-5 expression is increased in patients with advanced heart failure and contributes to adverse ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2009;119:408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.822072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wettschureck N, et al. Absence of pressure overload induced myocardial hypertrophy after conditional inactivation of Galphaq/Galpha11 in cardiomyocytes. Nat Med. 2001;7:1236–1240. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harada K, et al. Pressure overload induces cardiac hypertrophy in angiotensin II type 1A receptor knockout mice. Circulation. 1998;97:1952–1959. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.19.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crowley SD, et al. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17985–17990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vandeput F, et al. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase PDE1C1 in human cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32749–32757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandeput F, et al. cGMP-hydrolytic activity and its inhibition by sildenafil in normal and failing human and mouse myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:884–891. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lukowski R, et al. Role of smooth muscle cGMP/cGKI signaling in murine vascular restenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1244–1250. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qiu P, Feng XH, Li L. Interaction of Smad3 and SRF-associated complex mediates TGF-beta1 signals to regulate SM22 transcription during myofibroblast differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1407–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.