Abstract

Objective

To examine the operating characteristics of the Patient Health Questionnaire eating disorder module (PHQ-ED) for identifying bulimia nervosa/binge eating disorder (BN/BED) or recurrent binge eating (RBE) in a community sample, and to compare true positive (TP) versus false positive (FP) cases on clinical validators.

Method

259 screen positive individuals and a random sample of 89 screen negative cases completed a diagnostic interview. Sensitivity, specificity, and Positive Predictive Value (PPV) were calculated. TP and FP cases were compared using t-tests and Chi-Square tests.

Results

The PHQ-ED had high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (92%) for detecting BN/BED or RBE, but PPV was low (15% or 19%). TP and FP cases did not differ significantly on frequency of subjective bulimic episodes, objective overeating, restraint, on BMI, and on self-rated health.

Conclusions

The PHQ-ED is recommended for use in large populations only in conjunction with follow-up questions to rule out cases without objective bulimic episodes.

Keywords: Patient Health Questionnaire, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, recurrent binge eating, screening, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Bulimic spectrum disorders (i.e., threshold or sub-threshold bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED)) have been shown to be associated with psychiatric comorbidity as well as health and psychosocial impairment.1-5 Although effective treatments are available,6-9 these eating disorders often go undetected and untreated10-12 which has prompted experts to call for early identification through outreach and screening efforts.12

A myriad of assessment tools has been developed to measure eating pathology, yet evidence of their utility for case detection is limited and no uniformly accepted screening tool for eating disorders has emerged.13 Many instruments emphasize symptoms characteristic of anorexia nervosa and most were developed before BED was introduced into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as a disorder in need of further study. The Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE)14 is widely regarded as the “gold standard” measure for making an eating disorder diagnosis15 and its self-report questionnaire version, the EDE-Q16 has gained increasing popularity for measuring eating disorder symptoms in both clinical and epidemiological studies because of the significant time burden associated with the interview version. Mond recently reported on the utility of the EDE-Q as a screener in community17 and primary care18 samples. Although the reported values for specificity, sensitivity, and positive predictive value were favorable, the instrument's length of 35 items makes it still quite burdensome for use as a screener.

Eating disorder screens are particularly needed for primary care settings for several reasons. One, although they typically do not receive treatment specifically for the eating disorder, studies have shown that individuals with an eating disorder tend to utilize more health services than individuals without an eating disorder19 and for most patients primary care providers represent the “point of entry” into the health care system.20 Hence, primary care providers play a pivotal role in treating patients or referring patients into specialty treatment. Two, prior research has shown that patients prefer being treated for their eating disorder in the primary care setting.12 Three, evidence suggests that primary care providers often do not detect the eating disorder (or, for that matter, other mental health problems), possibly at least in part because of the time pressure under which the providers have to deliver their health care services.11

An important consideration in choosing a diagnostic screening instrument for use in a medical setting is the ability to balance respondent and medical staff burdens with the accuracy of the instrument. Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and colleagues21 advocated use of a self-report questionnaire (Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ) they developed based on a general screening interview for common mental disorders (PRIME-MD). Comprised of brief modules assessing the most common mental disorders, the PHQ was designed to permit selective use of modules if one is interested in diagnosing a particular disorder rather than screening for multiple disorders. Some of the modules (e.g., mood disorders) have been subjected to extensive testing22-24 and translated into numerous languages.25, 26

Notwithstanding the widespread use of the PHQ for general screening for mental disorders in general, or for mood disorders in particular, few studies have used the PHQ eating disorder module (PHQ-ED) as a screening tool. The sensitivity (89%) and specificity (96%) of this screening module was determined based on a subset of patients (number not reported) using the PRIME-MD interview for validation21. One aim of the present study was to determine the operating characteristics of the PHQ-ED module when used for screening a sample of members of a large health maintenance organization and when compared against the EDE (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). Because of the growing interest in broadening the diagnostic criteria for BN or BED based on binge frequency, in the present study we examined the operating characteristics both for current definitions of BN/BED (requiring an average twice weekly binge frequency, as well as additional behavioral or cognitive symptoms, as specified in the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, DSM-IV) and for a more inclusive diagnostic category entitled recurrent binge eating (RBE) requiring solely the presence of at least one binge eating episode per week on average for three months with no gaps between binge episodes exceeding two weeks.

Few studies have examined how individuals who screen positively for the presence of an eating disorder but do not meet diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder (“false positive” cases) differ from individuals who both screen positively and meet diagnostic criteria based on rigorous diagnostic evaluation (“true positive” cases). Therefore, as a secondary aim we compared false positive cases and true positive cases on eating disorder symptoms, body mass index (BMI), and self-reported health.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Potential participants were randomly selected from the electronic health record (EMR) system of a large health maintenance organization, using criteria specified below. Excluded from the recruitment were individuals whose medical records indicated severe cognitive impairment (e.g., mental retardation), or those currently receiving treatment for a severe physical illness such as cancer. Also excluded were approximately 100 plan members whose records indicated that they had pre-emptively opted out of any involvement in research. Potential participants had to have been continuously insured by the health plan for the 12 months prior to selection.

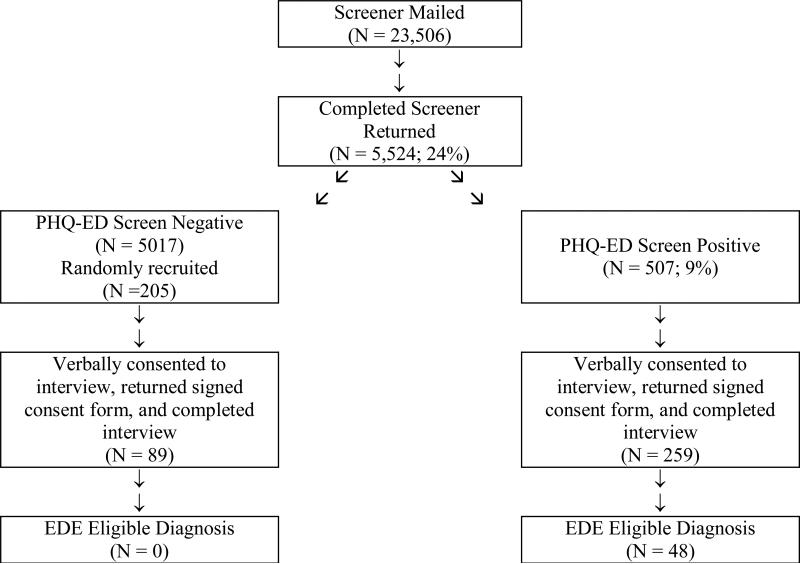

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the recruitment process. Beginning in June 2004 and ending in July 2005, letters were sent to male and female health plan members between 18 and 35 years of age (the population of adults for whom community epidemiological studies suggest the highest rates of binge eating disorders)1, 27 inviting them to complete a brief self assessment about their eating habits, body shape and weight concerns, and other health and demographic factors. Participants who met PHQ-ED criteria for BN, BED, or RBE were invited to participate in an in-depth assessment using a state-of-the-art diagnostic interview. In order to examine the psychometric properties of the PHQ-ED in this population, a random sample of individuals who screened negative was also recruited to complete the diagnostic assessment. The final sample consisted of a total of 348 participants, 259 screen positive cases and 89 screen negative cases. The participants were primarily white (87%), non-Hispanic (93%) women (82%), with at least some college experience (80%) and an average age of 28.18 (SD = 5.38).

Figure 1.

Screening/Diagnosis Rates for Phase 1 of the Study

Measures

Initial screening questionnaire

The PHQ-ED21 is comprised of six binary (yes/no) response items concerning binge eating and compensatory behaviors asked of everyone and up to two follow-up questions asked when binge eating or purging are endorsed. To assess binge eating, participants were asked to indicate if they often feel that they can't control what or how much they eat (loss of control) and if they often eat, within any 2-hour period, what most people would regard as an unusually large amount of food (overeating). Participants responding ‘yes” to both of these items are then asked to indicate if the behaviors in question occurred as often as twice a week in the last three months. Focusing on the past three months, respondents are asked to indicate whether they vomited, took laxatives, fasted, or exercised in order to avoid gaining weight after binge eating and, if yes, whether any of these behaviors occurred at least as often as twice a week on average during the past three months.

The PHQ-ED was augmented with three questions to further describe the eating pathology and general health of our sample, as well as with items assessing height, weight, overall health, and demographic information (date of birth, gender, race, ethnicity, education, marital status). Experts have called for a re-evaluation of the frequency criterion for binge eating for making a diagnosis of BN or BED5. In order to identify participants who engage in binge eating behaviors at a frequency below the diagnostic threshold, the PHQ-ED was expanded to include an item asking participants to indicate if the binge eating occurred as often as once a week in the past three months. An additional item, adapted from the EDE-Q16, was included to assess dietary restriction. Participants indicated (yes/no) whether they consciously tried to limit the amount of food eaten in order to influence their shape or weight over the prior three months. Finally, participants were asked to rate their general health (1 = excellent, 5 = poor) over the prior three months. Binary demographic categories were created as follows: White (yes/no), Hispanic (yes/no), currently married or partnered (yes/no), and high school graduate or less vs. some college or more.

Diagnostic assessment

The EDE14, 12th edition with text edits from the 14th and 15th editions, was administered by telephone to validate eating disorder diagnoses. This standardized, semi-structured, investigator-based interview measures the presence and severity of the core clinical features of eating disorders, and is considered the “gold standard” method for assessing ED psychopathology. Specifically, the diagnostic items of the interview were utilized to determine whether participants met DSM-IV criteria for BN, BED, or study criteria for RBE. Interviewers were blind to participant responses on the PHQ-ED.

Analysis

The software package SPSS (15.0) was used for all analyses. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the PHQ-ED were calculated based on the original PHQ-ED items. Sensitivity (“true positive rate”) refers to the probability that an individual would screen positive if a binge eating disorder is actually present (as determined by EDE interview). Specificity (“true negative rate”) is the probability that an individual would screen negative if a binge eating disorder is not present. The positive predictive value (PV+) represents the probability that an individual classified as a case by the screener is also classified as a case by the EDE interview, and negative predictive value (PV−) that an individual classified as a noncase by the screener remains a noncase in the interview. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated adjusting for the sampling; as discussed by Kraemer28, it is important to take the sampling into account, particularly for low prevalence conditions like eating disorders.

In an effort to describe individuals who self-reported binge eating on the PHQ-ED failed to qualify for a diagnosis of a binge eating disorder, we compared “true positive” participants and “false positive” participants on measures of the frequency of three types of eating episodes, as measured by the EDE: OBEs (eating episodes involving both a sense of loss of control and eating objectively large amounts of food), subjective bulimic episodes (SBEs, eating episodes involving a sense of loss of control while eating amounts of food that are experienced by the participant as “large” but deemed by research criteria as below the threshold required for OBEs), and Objective Overeating (OO, eating episodes involving consumption of an objectively large amount of food in the absence of a sense of loss of control). The two groups also were compared on eating restraint, BMI, and self-rated health. Cohen's d29 was used to estimate effect size.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distribution of participants across the possible screen (PHQ-ED) and interview (EDE) outcomes. The operating characteristics of the PHQ-ED as a screen for identifying BN/BED or RBE (which includes BN/BED) were as follows. For either diagnostic outcome, the sensitivity was 100%; specificity was 91.7% (BN/BED) and 92.4% (RBE). Although our analyses suggest that the probability that a person does not have an eating disorder given a negative screen is 100%, the probability that a person meets interview assessed criteria for BN/BED or RBE given a positive screen is fairly low (PPV = 0.145 and PPV = 0.185).

Table 1.

Distribution of participants across PHQ-ED and EDE outcomes

| EDE Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BED or BN | RBE | |||

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

| PHQ-ED Screen + | 27 | 232 | 48 | 211 |

| PHQ-ED Screen − | 0 | 89 | 0 | 89 |

*PHQ-ED Screen + = participant endorsed overeating with loss of control at least once per week over the last month; PHQ-ED Screen − = participant reported neither overeating and/or loss of control or endorsed these behaviors but not at the required minimum threshold of once per week over the last month.

As shown in Table 2, false positive cases had significantly fewer days with OBEs (a strong effect) than true positive cases. The two groups did not differ significantly on number of days with SBEs, episodes of objective overeating, mean BMI, or average self-rated health. Prevalence of dietary restraint did not differ significantly (χ2(1)=.046, p = .83): a majority of false positive cases (83.0%) and true positive cases (81.6%) indicated that in the past 3 months they had been consciously trying to limit the amount of food they ate to influence their shape or weight.

Table 2.

Comparison of True Positive Cases and False Positive Cases on Number of Days with Binge Eating or Overeating Episodes, Body Mass Index (BMI), and Self-Rated Health

| True Positive Mean (SD) N=48 | False Positive Mean (SD) N=211 | t(df) | p-value | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBE | 11.67 (7.88) | 0.42 (1.46) | t(257) = 19.43 | < .0001 | 1.99 |

| SBE | 5.70 (7.54) | 4.02 (6.62) | t(255) = 1.52 | .13 | .24 |

| OO | 0.96 (3.34) | 0.76 (2.54) | t(256) = 0.46 | .65 | .07 |

| BMI | 31.76 (8.84) | 31.92 (7.85) | t(253) = −0.13 | .90 | −.02 |

| Health | 3.35 (1.08) | 3.10 (1.05) | t(254) = 1.50 | .14 | .23 |

Note: OBE = Objective Bulimic Episode; SBE = Subjective Bulimic Episode; OO = Objective Overeating; true positive cases screened positive for a binge eating disorder (i.e., bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), or recurrent binge eating (RBE)) on the PHQ-ED and were found to meet diagnostic criteria for BN or BED or for RBE on the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE); false positive cases screened positive for a binge eating disorder on the PHQ-ED but were found to not meet diagnostic criteria for a binge eating disorder on the EDE.

Discussion

Epidemiological studies have shown that eating disorders involving binge eating as the core behavioral symptom (i.e., bulimia nervosa, BED, and their subthreshold variants) are the most common forms of eating disorders1, 27 and that these eating disturbances are associated with personal and social suffering.5 To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study of the psychometric properties of the eating disorder module of the PHQ for detecting such binge eating disorders. The PHQ-ED has the advantage of being brief (thus taking up little of participants time) and readily available at no cost. We recruited a random sample of young adults, the age group most likely to experience a binge eating disorder,27 from a large health maintenance organization with a socioeconomically diverse membership. Our findings suggest that the PHQ-ED is highly sensitive: not a single person among those who screened negative was found to experience recurrent binge eating or meet full-syndrome criteria for BN or BED. If the goal is to ensure that no one with recurrent binge eating is being missed during a screening, the PHQ-ED is a suitable tool. On the other hand, the results concerning the PPV are disappointing. The PHQ-ED “casts a wide net,” identifying many individuals as potential cases who upon diagnostic evaluation were found not to meet case criteria. This is consistent with results from studies using other eating disorder screens, although in several studies PPV was not calculated separately for community cases versus patient samples, a practice that would inflate PPV values.13 As discussed by Jacobi, Abascal and Taylor,13 PPV for identifying cases is highly population dependent and for low prevalence disorders PPV values are low even when sensitivity and specificity are excellent. It is possible that the PHQ-ED has far more favorable PVV among patients requesting treatment for an eating disorder. When used among community samples a positive screen response, in the absence of additional follow-up assessment, should not be interpreted as presence of a current binge eating disorder.

Our data offer a few clues as to why some respondents self-report often eating a large amount of food and experiencing loss of control over how much they eat yet do meet criteria for recurrent binge eating upon interview. Because the definition of RBE rested on the presence of binge eating, it was to be expected (as indeed we found) that false positive cases, compared to true positive cases, would report significantly fewer days with objective bulimic episodes. It is of note, that on average, false positive cases reported four days with SBEs, and our inclusion into the second stage of the assessment required a positive response to the questions of whether, on average, eating an unusually large amount of food within a 2-hour period and loss of control over eating had occurred at least once a week for the last 3 months. Hence, false positive cases may have considered smaller amounts of food as “unusually large” yet upon interview those episodes were deemed to involve insufficient amounts of food to be considered “objectively large.” Prior studies have shown that a lay person's definition of binge eating is broader than the expert definition, underscoring the difficulty of measuring binge eating in the absence of providing study participants with an operational definition of “unusually large.”30, 31 Hence, based on self screening, a high rate of false positive cases should be expected unless highly detailed definitions of binge eating (including specific amounts of foods consumed during the overeating episode) are provided as part of the screening. However, providing for the myriad of possible eating episodes encountered when assessing over eating, it likely will prove impractical to develop a screening tool that substantially reduces the rate of false positive cases.

Notwithstanding the group differences in the frequency of objective bulimic episodes, the two groups did not differ on BMI or self-rated health, two commonly used indicators of clinical significance. Further, in both groups most participants reported high levels of dietary restraint. The average BMI values suggest that these participants were overweight or obese. Thus, the PHQ-ED appears to identify individuals who might benefit from interventions focused on weight management.

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. Recruitment rates were disappointingly low in this epidemiological phase when participants were invited from the membership rosters rather than being approached more directly through primary care clinics and we were unable to address the question of systematic recruitment biases. Our sample included predominantly white individuals; our findings therefore cannot be generalized to ethnic minority samples. These limitations notwithstanding, our study offers the first systematic effort to test whether the PHQ, a widely used screener, may be useful for identifying eating disorders in the community. Our answer to this question is a qualified “yes” because despite its favorable specificity the PHQ-ED likely will yield a very high false positive rate when used among non-treatment seeking populations. Additional research is needed to determine whether the PPV of this or other screening tools can be enhanced, for example by offering specific definitions of what constitutes a binge eating.32, 33

Acknowledgements

Supported by MH066966 (to principal investigator R.S.M.) from the National Institutes of Health and by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (awarded to Kaiser Foundation Research Institute). The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official of the NIH, NIMH, NIDDK, or the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute.

References

- 1.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr., Kessler RC. The Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt U, Lee S, Perkins S, Eisler I, Treasure J, Beecham J, et al. Do adolescents with eating disorder not otherwise specified or full-syndrome bulimia nervosa differ in clinical severity, comorbidity, risk factors, treatment outcome or cost? Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:498–504. doi: 10.1002/eat.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spoor ST, Stice E, Burton E, Bohon C. Relations of bulimic symptom frequency and intensity to psychosocial impairment and health care utilization: Results from a community-recruited sample. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:505–514. doi: 10.1002/eat.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaught AS, Agras W, Bryson SW, Crow SJ, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE. Changes in psychopathology and symptom severity in bulimia nervosa between 1993 and 2003. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:113–117. doi: 10.1002/eat.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilfley DE, Bishop ME, Wilson G, Agras W. Classification of eating disorders: Toward DSM-V. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:S123–S129. doi: 10.1002/eat.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Binge eating disorder treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:337–348. doi: 10.1002/eat.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321–336. doi: 10.1002/eat.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sysko R, Walsh B. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson G, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garvin V, Streigel-Moore RH. Health services research for eating disorders in the United States: A status report and a call to action. In: Striegel-Moore RH, Smolak L, editors. Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001. [References] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson J, Spitzer R, Williams J. Heath Problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1455–1466. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Health service utilization for eating disorders: Findings from a community-based study. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:399–408. doi: 10.1002/eat.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobi C, Abascal L, Taylor C. Screening for Eating Disorders and High-Risk Behavior: Caution. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:280–295. doi: 10.1002/eat.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Binge Eating and Bulimia Nervosa: Distribution and Determinants. In: Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, editors. The eating disorders examination. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilfley DE, Schwartz MB, Spurrell EB, Fairburn CG. Using the Eating Disorder Examination to identify the specific psychopathology of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:259–269. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<259::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mond J, Hay P, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont P. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mond JM, Myers TC, Crosby RD, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Morgan JF, et al. Screening for eating disorders in primary care: EDE-Q versus SCOFF. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon J, Schmidt U, Pilling S. The health service use and cost of eating disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1543–1551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Striegel-Moore R, DeBar L, Wilson G, Dickerson J, Rosselli F, Perrin N, et al. Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1465–1474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron I, Crawford J, Lawton K, Reid I. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:32–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbody S, Richards D, Barkham M. Diagnosing depression in primary care using self-completed instruments: UK validation of PHQ-9 and CORE-OM. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:835–836. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittkampf KA, Naeije L, Schene AH, Huyser J, van Weert HC. Diagnostic accuracy of the mood module of the Patient Health Questionnaire: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnelly P. The use of the Patient Health Questionnaire--9 Korean Version (PHQ-9K) to screen fr depressive among Korean Americans. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18:324–330. doi: 10.1177/1043659607305191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoek HW, van Hoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:383–396. doi: 10.1002/eat.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer H. Evaluating Medical Tests: Objective and Quantitative Guidelines. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dohm F-A, Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH. Factors That Influence Food Amount Ratings by White, Hispanic, and Asian Samples. Obes Res. 2005;13:1061–1069. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson WG, Carr-Nangle RE, Nangle DW, Antony MM, Zayfert C. What is binge eating? A comparison of binge eater, peer, and professional judgments of eating episodes. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:631–635. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldfein JA, Devlin MJ, Kamenetz C. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire with and without Instruction to Assess Binge Eating in Patients with Binge Eating Disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:107–111. doi: 10.1002/eat.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldschmidt AB, Doyle AC, Wilfley DE. Assessment of binge eating in overweight youth using a questionnaire version of the child eating disorder examination with instructions. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:460–467. doi: 10.1002/eat.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]