Abstract

The distribution and activities of morphogenic signaling proteins such as Hedgehog (Hh) and Wingless (Wg) depend on heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). HSPGs consist of a core protein with covalently attached heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. We report that the unmodified core protein of Dally-like (Dlp), an HSPG required for cell-autonomous Hh response in Drosophila embryos, alone suffices to rescue embryonic Hh signaling defects. Membrane tethering but not specifically the glycosylphosphatidylinositol linkage characteristic of glypicans is critical for this cell-autonomous activity. Our studies further suggest divergence of the two Drosophila and six mammalian glypicans into two functional families, an activating family that rescues cell-autonomous Dlp function in Hh response and a family that inhibits Hh response. Thus, in addition to the previously established requirement for HSPG GAG chains in Hh movement, these findings demonstrate a positive cell-autonomous role for a core protein in morphogen response in vivo and suggest the conservation of a network of antagonistic glypican activities in the regulation of Hh response.

Keywords: glypicans, heparan sulfate proteoglycans

Segmental patterning in the Drosophila embryo requires an appropriate response to the Hedgehog (Hh) ligand, which is mediated at the cell surface by synergistic binding to Patched (Ptc) and a member of the Interference hedgehog (Ihog) family (1, 2). Hh binding to Ptc relieves its suppression of the transmembrane (TM) protein Smoothened (Smo), leading to Hh-dependent transcriptional activation (3). Recently, several studies have suggested that another cell surface protein, the heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) Dally-like (Dlp), is also essential for Hh response. An absolute requirement for Dlp but not for the related protein Dally in Hh response has been observed in wing imaginal disc-derived cl-8 cells and in the embryonic ectoderm (4–6). In contrast, in intact wing imaginal discs, Dlp and Dally each can contribute to but is not absolutely required for Hh signaling (6–8). Notably, the unique requirement for Dlp in Hh response is distinct from its functionally overlapping role (with Dally) in Hh gradient formation in the wing imaginal disc (6, 9).

Dlp and Dally are the Drosophila representatives of the glypican HSPG family, which consists of six unique polypeptides in mammals and is characterized by an N-terminal globular domain with 14 conserved cysteine residues, an extended C-terminal domain encoding membrane-proximal glycosaminoglycan (GAG) attachment sites, and a C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage that tethers the protein to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (9). The structural features of the mature Dally and Dlp proteins that contribute to their specific activities in Hh gradient formation and cell-autonomous response remain unclear.

The stringent requirement for Dlp but not Dally function in Hh response in embryonic ectoderm and cl-8 cells is representative of a larger trend in which related members of particular proteoglycan families have evolved significant specialization with respect to some signaling activities in spite of their similarity in overall sequence, structure, and GAG modification. Perhaps the clearest evidence for proteoglycan function in extracellular signaling is the demonstration that GAG chains but not the specific core protein to which they are attached participate in the interaction of FGF with its receptor (9). Such data suggest that HSPG core proteins can function largely as inert and interchangeable scaffolds. However, other evidence suggests that both core proteins and GAG chains may contribute to Hh signaling (see below) and to canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling (10–15). For example, loss of GAG modification clearly disrupts Hh ligand movement in Drosophila (9), although a specific requirement for GAG chains or core protein in cell-autonomous response in vivo has not been established. In addition, although the Drosophila perlecan Trol, an HSPG in the extracellular matrix, functions in Hh signaling during larval brain development (16), it is apparently not required for cell-autonomous response in cultured cells (4). The picture emerging from these and other examples (9, 17) is that vertebrate and invertebrate HSPGs have diverse and specialized roles in ligand movement and sequestration, in ligand-receptor stabilization, and perhaps in other roles, demonstrating both positive and negative activities in cell-autonomous response and extracellular ligand trafficking. This complexity raises one of the most significant unanswered questions in the field of proteoglycan research: What are the relative contributions of the core proteins and GAG modifications of closely related HSPGs to their physiological activities?

Using Drosophila Hh signaling as a tractable model system, we examine here the relative contributions of the Dlp core protein and several of its structural features to cell-autonomous Hh response as well as the conservation of positive and negative activities for both Drosophila and mammalian glypicans in Hh response.

Results

Dlp Core Protein Rescues Cell-Autonomous Hh Response.

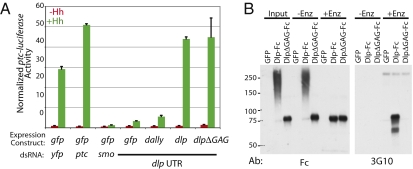

Consistent with a previous RNAi screen (4) and with studies in the embryonic ectoderm (5, 6), RNAi-mediated depletion of dlp mRNA in cultured Drosophila cl-8 imaginal disc cells resulted in a loss of Hh response (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, Hh response can be rescued and even increased by overexpression of a FLAG epitope-tagged form of dlp but not dally (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

Dlp core protein is uniquely required for Hh response. (A) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay shows that dlp or dlpΔGAG fully rescues Hh response in the presence of dlp UTR dsRNA, whereas gfp and dally do not. Control dsRNA treatments for neutral (yfp), negative (ptc), and positive (smo) effectors are shown. Red and green bars show ptc-luciferase reporter levels with control and HhN-conditioned medium treatments, respectively, normalized to a constitutive copia-Renilla luciferase reporter. Transfections were done in triplicate, and the values were averaged. Error bars show variability within each triplicate. A representative experiment is shown. (B) DlpΔGAG-Fc shows no detectable heparan sulfate (HS) modification. Fc fusion proteins or control GFP expressed in COS-1 cells was incubated with (+Enz) or without (−Enz) heparitinase I and III and chondroitinase ABC and analyzed by reducing SDS/PAGE and Western blotting to detect Fc (Left, Fc) or the HS core fragment produced by enzymatic treatment (Right, 3G10). Molecular weight markers are indicated.

Given that GAG chain modification of Dlp has been implicated in cell nonautonomous Hh movement, we tested GAG chain contribution to cell-autonomous Hh response by creating DlpΔGAG, a Dlp variant in which the serine residues in all five consensus Ser-Gly GAG attachment motifs (18) were altered to alanine. Expression of WT Dlp in COS-1 cells produces a protein that migrates as a smear of higher molecular weight species characteristic of GAG-modified proteins, whereas DlpΔGAG, consistent with the absence of GAG modification, migrates as a discrete band with electrophoretic mobility identical to that of WT Dlp treated with heparitinase and chondroitinase ABC (Fig. 1B). The 3G10 antibody that recognizes the desaturated uronic acid ends remaining after heparitinase digestion of heparan sulfate-modified polypeptides (19) furthermore shows no immunoreactivity in enzyme-treated samples expressing DlpΔGAG, in contrast to Dlp (Fig. 1B). Similar results were observed with expression in Drosophila cultured cells (Fig. S1B).

We found that DlpΔGAG fully rescues dlp RNAi in our cultured cell Hh signaling assay and furthermore potentiates Hh-dependent reporter expression as well as WT Dlp when expressed at a comparable level (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A). GAG chain modification is therefore dispensable for the activity of Dlp in cell-autonomous Hh response in cultured cells.

Additional Glypican Structural Features Are Dispensable for Hh Response.

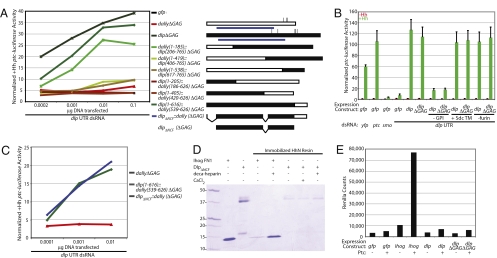

We further characterized the structural features of Dlp necessary for Hh response by creating six GAG-deficient chimeras with the structurally similar but functionally divergent protein Dally (Fig. 2A). Because the expression levels of these chimeras varied considerably (Fig. S2A), we assayed their activities in rescuing dlp RNAi over a 500-fold range of transfected DNA (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2B). The Dlp(1–616)::Dally(539–626) and Dally(1–185)::Dlp(206–765) chimeras have ∼90% and ∼70%, respectively, of the activity of WT Dlp, whereas the other chimeras showed little to no activity. Overall, our data suggest that Dlp residues 206–616 are critical for Dlp function in Hh response.

Fig. 2.

Structure-function studies delineate a truncated domain of Dlp that is active in Hh response but fails to bind HhN in vitro. (A) (Right) Schematic diagram shows Dally-Dlp ΔGAG chimeras and Dlp truncations generated. White, Dally; black, Dlp; vertical lines, GAG attachment sites (mutated); blue lines, domains containing the 14 conserved Cys residues (69–474 in Dally and 80–553 in Dlp); v-shaped lines, deleted domains. (Left) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay shows the relative activities of the chimeras in rescuing Hh response in the presence of dlp UTR dsRNA over a 500-fold range of expression construct transfected. Values shown are normalized ptc-luciferase levels in the presence of HhN-conditioned medium. Rescue by 0.01 μg of DNA is shown in Fig. S2B. (B) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay shows the relative activities of Dlp derivatives in rescuing Hh response in the presence of dlp UTR dsRNA. −GPI, deletion of the GPI attachment domain; +Sdc TM, replacement of the GPI attachment domain with an Sdc TM domain; −furin, furin cleavage site RERR mutation to GEGG. Reporter assay details are presented in Fig. 1. (C) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay shows the relative activity of DlpΔNCF::Dally (blue) in rescuing Hh response in the presence of dlp UTR dsRNA over a 100-fold range of expression construct transfected. Values shown are normalized ptc-luciferase levels in the presence of HhN-conditioned medium. (D) Purified immobilized HhN specifically retains Ihog FN1 but not DlpΔNCF in the presence of deca-heparin, based on SDS/PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of eluted proteins. Molecular weight markers are indicated. (E) No significant HhN-Ren binding to cultured cells expressing Dlp or DlpΔGAG with or without Ptc is detected, whereas Ihog alone or in combination with Ptc shows significant binding. Values shown are actual bound Renilla counts.

GPI-linked proteins are subject to specific subcellular localization and trafficking processes and can be released from the membrane by phospholipase C or other enzymes (14, 20, 21). This cell shedding can lead to gain of a cell nonautonomous activity (8) or to down-regulation of a cell-autonomous activity (13, 20–23). We examined the requirement for GPI-mediated membrane tethering of Dlp by deleting the GPI attachment signal or replacing it with the TM domain from the HSPG Syndecan (Sdc) and found that Sdc TM domain-tethered Dlp is fully functional, whereas a soluble form is not. These data suggest that membrane tethering but not specifically GPI linkage is necessary for the activity of Dlp in Hh response in cultured cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3A). Like WT Dally, neither Dally nor DallyΔGAG lacking the GPI tether shows activity (Fig. S3B).

Gallet et al. (7) reported that a Dlp construct with its GPI anchoring sequence replaced by 323 residues of the CD2 cell adhesion protein, including a TM domain, failed to rescue and actually acquired a trans-dominant negative effect in the wing imaginal disc, where Dlp has a significant cell nonautonomous role in Hh movement (6). We tested this and several other constructs (Fig. S4A) and found that all Dlp proteins anchored in any way to the membrane are functional in our cultured cell assay, which is a pure test of Hh response. The Dlp-CD2 fusion was not tested in the embryo (7), and its unusual activity in the wing imaginal disc might be attributable to the presence of extensive CD2 sequences and/or the complex dual roles of Dlp in Hh transport and response in the wing imaginal disc.

Glypicans also can undergo endoproteolytic processing by a furin-like convertase, which is thought not to lead to shedding from the membrane but can be essential for activity (14). This feature appears dispensable for Dlp function in Hh response in cultured cells, because we observed no detrimental effect of alteration of the Dlp consensus furin cleavage site Arg-X-Arg-Arg (24) to Gly-X-Gly-Gly (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4B).

Dlp Core Protein Does Not Interact with the N-Terminal Fragment of the Hh Ligand.

We have previously observed a weak interaction in vitro between GAG-modified Dlp and HhN (4), the active N-terminal fragment of the Hh ligand (25). Given that HhN interacts with sulfated sugars (26) like the GAG chain modifications of Dlp, we further investigated whether Dlp core protein lacking GAG modification can also contribute to Hh binding. We assayed for direct binding using a purified truncated fragment of Dlp with mutated GAG attachment sites. To facilitate expression and purification, this truncated form, DlpΔNCF, lacks the N-terminal 73 residues, the residues C-terminal to residue 617, and the residues between a putative cryptic cleavage site and the consensus furin cleavage site (residues 400–437). We fused DlpΔNCF to a heterologous signal sequence and supplied the requisite plasma membrane tether (see above) by adding DallyΔGAG residues 539–626, and thus generated DlpΔNCF::Dally. This variant is abundantly expressed in Drosophila cells (Fig. S5A) and is capable of rescuing Hh response in the presence of dlp RNAi (Fig. 2C), demonstrating that all Dlp domains necessary for cell-autonomous response are present within DlpΔNCF. Whereas the HhN-binding FN1 domain of Ihog binds strongly to immobilized HhN in the presence of soluble heparin (2) (Fig. 2D), specific binding of purified DlpΔNCF to immobilized HhN is undetectable at DlpΔNCF concentrations of 25 μM, even in the presence of soluble heparin or Ca+2 (Fig. 2D), the latter of which has been shown to stabilize HhN in its native conformation (27). Similarly, we have been unable to observe substantial interaction between HhN and DlpΔGAG in a variety of cell-based binding experiments. For example, when Dlp was overexpressed by transfection into cultured cells, an enzyme-tagged form of HhN (HhN-Ren, fused to Renilla luciferase) showed very little increase in cell binding (Fig. 2E). As with untagged HhN in the presence of WT Dlp, however, cell-autonomous response to HhN-Ren can be potentiated by the presence of Dlp, suggesting that the Renilla fusion protein has Dlp-dependent signaling ability (Fig. S5B). We also know that HhN-Ren is competent to bind to cells in an Ihog-dependent manner (1) (Fig. 2E). Thus, if Dlp core protein functions in Hh response by binding to HhN, this interaction is very weak and/or requires additional factors not yet identified.

Dlp Core Protein Rescues Hh Signaling in Vivo.

Having shown that the Dlp core protein is as active as WT Dlp in Hh response in cultured cells, we assayed core protein activity in vivo by generating transgenic flies with UAS-driven expression of Dlp or DlpΔGAG. These UAS-driven alleles showed equivalent expression and activity in cultured cells, although in transgenic embryos DlpΔGAG accumulated to approximately four to eight times the steady-state level of Dlp under control of the armadillo-GAL4 (arm-GAL4) driver (Fig. S6).

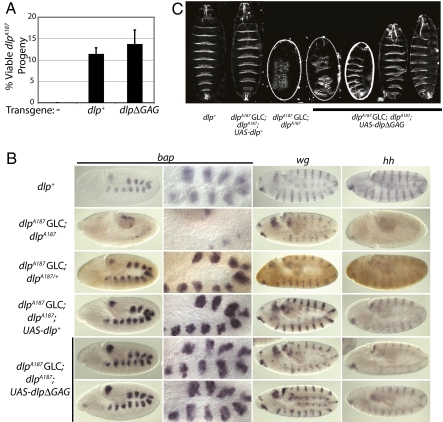

We tested expression of Dlp or DlpΔGAG for rescue of several dlp mutant phenotypes. Late larval lethality of zygotic dlpA187 null homozygotes (6) is rescued to adulthood equivalently by expression of core protein or WT Dlp (Fig. 3A), demonstrating significant core protein activity in vivo. The 12–14% rescue produced by either protein is less than the predicted Mendelian proportion of 20% (SI Materials and Methods), suggesting insufficiency of the arm-GAL4 driver to recapitulate fully the appropriate expression of Dlp in all tissues.

Fig. 3.

Dlp core protein is active in vivo. (A) Zygotic null dlpA187 embryos were rescued to adulthood equivalently by arm-GAL4-driven expression of UAS-dlp+ or dlpΔGAG based on the percentage of viable non-AntpHu adult flies. Full rescue is expected to generate 20% non-AntpHu progeny. Error bars depict variability between two to three independent crosses per genotype. (B) Double labeling of stage 10 embryos by in situ (purple) and with anti-GFP antibody (brown) showed rescue of bap, wg, and hh transcription by dlpΔGAG expression in dlpA187 GLC embryos. Anti-GFP reactivity distinguishes embryos with a paternal dlp+, Ubi-GFP chromosome. dlp+, w1118 embryos labeled only by in situ. dlpΔGAG-expressing embryos representing the worst (Upper) and best (Lower) phenotypes observed are shown. (C) Cuticle preparations show partial rescue of naked cuticle formation by dlpΔGAG expression in dlpA187 GLC embryos. Four cuticles representing the range of phenotypes observed with dlpΔGAG expression are shown. dlp+, w1118 embryos.

All embryos derived from homozygous maternal dlpA187 germline clones (GLCs) and carrying a paternal dlpA187 allele (referred to as dlpA187 GLC embryos) die during embryogenesis with hh-related patterning defects (6). Stage 10 dlpA187 GLC embryos show loss of expression of the mesodermal Hh-dependent transcript bagpipe (bap) and of both hh and wingless (wg), which maintain each other's expression at this stage of development (6, 28) (Fig. 3B). Subsequent cuticle deposition reveals a complete loss of segment polarity comparable to that of hh or wg null embryos (6) (Fig. 3C). All mutant phenotypes can be rescued by a single paternal dlp+ allele (Fig. 3B).

As seen in Fig. 3 B and C, expression of bap, hh, and wg and cuticle patterning in dlpA187 GLC embryos are fully rescued by arm-GAL4-driven UAS-dlp+ expression, whereas rescue to viability at the wandering larval (Fig. S7A) and adult (Fig. S7B) stages by UAS-dlp+ is somewhat reduced in frequency. Spatial restriction of bap expression in stage 10 embryos (28), which is dependent on Wg signaling, also is normal (Fig. 3B).

Expression of Dlp core protein in dlpA187 GLC embryos substantially rescues Hh-dependent bap, hh, and wg expression at stage 10, albeit with variability between embryos (Fig. 3B). All cuticles show some degree of restoration of the naked cuticle between denticle belts, with fusions between only a single pair of denticle belts in the best cases (Fig. 3C). Because naked cuticle within the posterior of each segment is lost with disruption of Hh signaling, the appearance of naked cuticle in rescued embryos indicates restoration of Hh signaling. Thus, although no UAS-dlpΔGAG-expressing embryos have a fully WT cuticle pattern or survive to the wandering larval stage (Fig. S7A), the Dlp core protein substantially rescues Hh-dependent signaling in dlp mutant embryos, demonstrating specific activity of the core protein in Drosophila Hh response.

Mammalian Glypicans Show Conserved Activating and Inhibitory Activities in Hh Response.

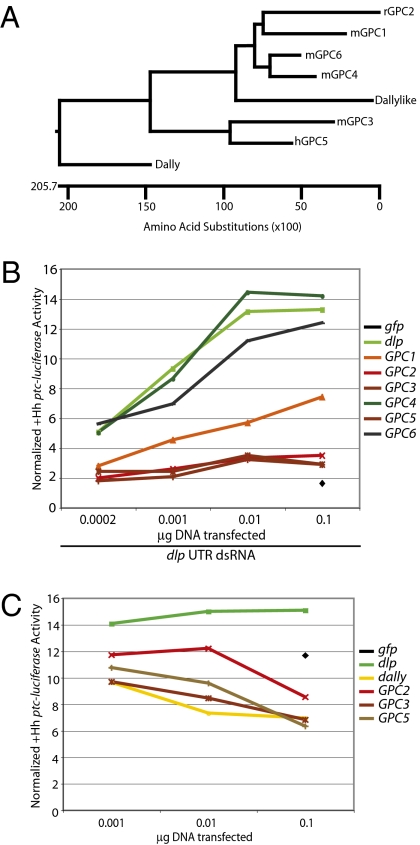

We next tested for rescue of dlp RNAi in our Drosophila cultured cell signaling assay by expression of the six mammalian glypicans, the physiological roles of which are poorly defined. Because steady-state accumulation of the glypicans in Drosophila cells varies considerably (Fig. S8A), rescue was assayed over a 500-fold range of transfected DNA. Although variability in glypican expression precluded determination of the absolute potencies of glypican rescue, we were able to identify trends clearly. We thus noted that GPC4 and GPC6, the closest relatives of Dlp (Fig. 4A), showed full dose-dependent rescue of Hh response, whereas GPC1 showed very weak activity and GPC2, GPC3, and GPC5 showed no activity (Fig. 4B and Fig. S8B). We further tested whether the rescue of Hh response by GPC4 and GPC6 required GAG chain modification by mutating GAG modification sites in these proteins and found that, like Dlp, GPC4 and GPC6 lacking GAG chains indeed are capable of partial or complete rescue (Fig. S9).

Fig. 4.

Mammalian glypicans show conserved activating and inhibitory activities toward Drosophila Hh response. (A) A cladogram shows the phylogenetic relationship between the mammalian and Drosophila glypicans. (B) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay using a 500-fold range of transfected expression constructs shows that dlp, GPC4, and GPC6 rescue Hh response in the presence of dlp UTR dsRNA; GPC1 partially rescues Hh response; and GPC2, GPC3, and GPC5 do not rescue Hh response. Rescue by 0.01 μg of DNA is shown in Fig. S8B. (C) A ptc-luciferase Hh reporter assay using a 100-fold range of expression construct transfected shows that dlp has trans-dominant positive activity toward Hh response, whereas dally, GPC2, GPC3, and GPC5 have trans-dominant negative activity. The dally construct is tagged with 3× FLAG, whereas the dlp and glypican constructs have a BM40 signal peptide and 1× HA tag. Results for all glypican with 0.1 μg of DNA transfected are shown in Fig. S8C. Reporter assay details are presented in Fig. 1. Values shown in B and C are the normalized ptc-luciferase levels in the presence of HhN-conditioned medium.

Because overexpression of GPC3 inhibits Sonic hedgehog (Shh) response in mice (29), we also assayed for trans-dominant inhibitory activity by cotransfecting the ptc-luciferase reporter together with expression constructs for other glypicans. We found that GPC3, as well as GPC2, GPC5, and Drosophila Dally, inhibited Drosophila Hh response in the presence of endogenous Dlp (Fig. 4C) to an extent comparable to that previously reported for effects on Shh signaling in mammalian cells (29). In contrast, expression of Dlp, GPC4, or GPC6 in the presence of endogenous Dlp potentiates response, and expression of GPC1, which weakly rescues Dlp depletion, is neutral (Fig. S8C). These data demonstrate striking conservation from insects to mammals of positive and negative activities for the mammalian glypicans in cell-autonomous Hh response.

Discussion

Previous work on the Drosophila glypicans Dally and Dlp has clearly demonstrated a role for these proteins in Hh signaling, but it has been difficult to distinguish activities in ligand movement vs. signal response and to assign these activities unambiguously to the glypican core proteins or to their GAG modifications. Genetic disruption of GAG biosynthesis or GAG modification or loss of both glypicans disrupts long-range Hh signaling but not cell-autonomous response (9), suggesting that the GAG modifications of these proteins function redundantly in Hh packaging and movement. We have focused here on the contribution of the Dlp core protein, and our data clearly demonstrate the ability of a core protein to rescue an essential glypican function in vivo. We show that Dlp core protein is active in Hh signaling in Drosophila embryos, and we specifically demonstrate, using cultured cells, that Dlp core protein functions in cell-autonomous Hh response.

Although weak interaction between GAG-modified Dlp and HhN has been observed previously and likely contributes to GAG-dependent Dlp activities, we failed to detect significant interaction between purified Dlp core protein and HhN. Although we cannot rule out that HhN-Dlp core protein interaction could occur in vivo, where nanoscale and higher order aggregation of HhN (30) could make weak interactions functionally relevant, we additionally failed to see evidence of significant HhN-Dlp interaction in cell-based binding assays. To date, we have been unable to enhance HhN-Ren binding to cells expressing Dlp or DlpΔGAG appreciably by increasing Ptc dosage, in contrast to the dramatic synergistic increase in binding observed to cells expressing Ihog. Overall, these data suggest that the Dlp core protein can contribute to cell-autonomous Hh response in a GAG-independent manner, perhaps through as yet unidentified protein interactions.

Beyond our studies on the Dlp core protein, we have shown that, despite their structural similarities, certain Drosophila and mammalian glypicans display opposing activities toward Hh response. The ability of mammalian GPC4 and GPC6 to rescue Dlp function in our Drosophila cultured cell assay is striking and seems particularly meaningful given that of all the mammalian glypicans these two are most closely related in sequence to Dlp. These mammalian glypicans are expressed in the developing lung, brain, limb, and other tissues (31, 32), all of which are locations consistent with potential roles in Hh patterning activities. Mutations affecting GPC6 recently were reported to be associated with the recessive human genetic disease omodysplasia (33), which consistently affects long bone growth and is associated with short stature. The features of omodysplasia are remarkably similar to the phenotypes of conditional Smo mutant mice in which Smo function, and consequently Hh response, is specifically inactivated in chondrocytes (34). Interestingly, the most prominent site of GPC6 expression in developing long bones is in the zone of proliferating chondrocytes within the growth plate (33); the proliferation of these chondrocytes is known to depend on response to Indian hedgehog (Ihh) expressed in the adjacent prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chon-drocytes (34). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the similarities between omodysplasia and the conditional inactivation of Smo in chondrocytes are attributable to similar defects in responsiveness to Ihh signaling.

Another human genetic disease, associated with mutation of GPC3, is the X-linked Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome (SGBS) (35), which has been modeled by targeted inactivation of GPC3 in the mouse (36, 37). In contrast to omodysplasia, SGBS is associated with persistent overgrowth, and GPC3 recently has been shown to inhibit Shh cell-autonomous response through binding to Shh and promotion of its endocytosis and degradation (29). Because GPC3 is also expressed in the chondrocytes of the growth plate (33), it seems possible that the overgrowth seen in patients who have SGBS could be attributable to enhanced activity of Ihh signaling.

As we have shown here, Dlp and its more closely related glypicans, such as GPC6, enhance Hh response in our Drosophila cultured cell assay, whereas Dally and the less closely related glypicans, including GPC3, exhibit trans-dominant negative activities. These patterns of sequence and functional conservation suggest that specific Drosophila and mammalian glypicans may have evolved distinctive activities in Hh response. Thus, in both vertebrate and invertebrate development, one could envision a system in which an intricate balance of activating and inhibitory glypicans modulates the ultimate readout of Hh pathway response in different tissues and at different times during development through effects on ligand movement, turnover, or activity. Our cultured cell system for analysis of glypican activities thus not only demonstrates a positive role for a glypican core protein in Hh response but may provide a useful model in which to characterize the network of response-promoting and -inhibiting activities of Drosophila and mammalian glypicans.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Hh Reporter Assays, and HhN-Ren Binding Assays.

The cl-8 and S2R+ cells were cultured, and cl-8 Hh reporter assays and S2R+ HhN-Ren binding assays were performed essentially as previously described (1, 4, 38). COS-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Further details can be found in SI Text.

Expression Plasmid Construction.

Constructs were expressed in Drosophila cells using the pAcSV vector, which contains the actin 5C promoter. Unless otherwise noted, all Dally and Dlp variants had a 3× FLAG epitope tag inserted following residues 26 and 47, respectively. pCDNA3 Fc fusion proteins were generated by fusing a human Ig Fc domain to residue 732 of Dlp. Dlp and the glypicans were cloned for expression in Drosophila cells by replacement of the endogenous signal peptide with residues 2–19 from mouse BM-40/osteonectin/SPARC (RAWIFFLLCLAGRALAAP), a dipeptide linker (LA), and 1× HA epitope tag (YPYDVPDYA). DlpΔNCF::Dally(539–626) was engineered to contain the same BM40 + HA domain as the glypicans fused to DlpΔGAG residues (74–399, 438–617) and DallyΔGAG residues (539–626). Further details can be found in SI Text.

Analysis of GAG Modification.

In COS-1 cells, C-terminal Fc fusions to −GPI variants of Dlp or DlpΔGAG or control GFP were expressed, whereas in S2R+ cells, −GPI variants of Dlp or DlpΔGAG or control GFP were expressed. Conditioned media were collected 2 days after transfection, incubated at 37 °C for 2 (COS-1) or 3 (S2R+) h with or without heparitinase I and III and chondroitinase ABC (Northstar Bioproducts, Associates of Cape Cod, Inc.), and analyzed by reducing (COS-1) or nonreducing (S2R+) SDS/PAGE and Western blotting. The −GPI variants were analyzed to reduce the complexity of the electrophoretic mobility pattern conferred by GPI linkage.

In Vitro Binding Assay.

Expression and purification of HhN and Ihog FN1 were performed as previously described (2). CHO cells stably expressing human growth hormone-DlpΔNCF fusion protein were generated, fusion protein was purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography, and purified DlpΔNCF was generated by cleavage with tobacco etch virus protease and subsequent affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. Purified Ihog FN1 or DlpΔNCF at 25 μM was bound to sepharose-immobilized HhN with or without 2 mM CaCl2 or 50 μM deca-heparin, the resin was washed, and bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Further details can be found in SI Text.

Drosophila Genetic and Phenotypic Analyses.

Details can be found in SI Text.

Immunoblotting and Antibodies.

Protein expression analyses were performed by transfection of S2R+ cells. All SDS/PAGE was performed under nonreducing conditions unless otherwise specified. Details can be found in SI Text.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

Megalign (DNAStar Lasergene) was used to perform a Clustal W alignment of full-length Dally, Dlp, and the glypicans and to generate the cladogram shown in Fig. 4A.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Lum (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), S. Saunders (Washington University School of Medicine), A. Lander (University of California at Irvine), Y. Yamaguchi (The Burnham Institute), M. Frasch (University of Erlangen-Nürnberg), X. Lin (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center), D. J. Pan (The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine), and P. Fisher (State University of New York at Stony Brook) for reagents; X. Lin for sharing results before publication; M. Fish (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine) for technical assistance with the fly experiments; B. Allen (Harvard University) for helpful suggestions on the manuscript; and S. Saunders for pointing out the similarity between loss of Smo in chondrocytes and omodysplasia. This work was supported by a Kirschstein National Research Service Award (to E.H.W.) and by a Kirschstein National Research Service Award and a Jane Coffin Childs Postdoctoral Fellowship (to W.N.P.). P.A.B. is an Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1001777107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yao S, Lum L, Beachy P. The ihog cell-surface proteins bind Hedgehog and mediate pathway activation. Cell. 2006;125:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLellan JS, et al. Structure of a heparin-dependent complex of Hedgehog and Ihog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17208–17213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606738103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia J, Jiang J. Decoding the Hedgehog signal in animal development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1249–1265. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5519-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lum L, et al. Identification of Hedgehog pathway components by RNAi in Drosophila cultured cells. Science. 2003;299:2039–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.1081403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desbordes SC, Sanson B. The glypican Dally-like is required for Hedgehog signalling in the embryonic epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:6245–6255. doi: 10.1242/dev.00874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han C, Belenkaya TY, Wang B, Lin X. Drosophila glypicans control the cell-to-cell movement of Hedgehog by a dynamin-independent process. Development. 2004;131:601–611. doi: 10.1242/dev.00958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallet A, Staccini-Lavenant L, Thérond PP. Cellular trafficking of the glypican Dally-like is required for full-strength Hedgehog signaling and wingless transcytosis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eugster C, Panáková D, Mahmoud A, Eaton S. Lipoprotein-heparan sulfate interactions in the Hh pathway. Dev Cell. 2007;13:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin X. Functions of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling during development. Development. 2004;131:6009–6021. doi: 10.1242/dev.01522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichsman F, Smith L, Cumberledge S. Glycosaminoglycans can modulate extracellular localization of the wingless protein and promote signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:819–827. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkpatrick CA, et al. The function of a Drosophila glypican does not depend entirely on heparan sulfate modification. Dev Biol (Amsterdam, Neth) 2006;300:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohkawara B, Yamamoto TS, Tada M, Ueno N. Role of glypican 4 in the regulation of convergent extension movements during gastrulation in Xenopus laevis. Development. 2003;130:2129–2138. doi: 10.1242/dev.00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6245–6254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Cat B, et al. Processing by proprotein convertases is required for glypican-3 modulation of cell survival, Wnt signaling, and gastrulation movements. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:625–635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song HH, Shi W, Xiang YY, Filmus J. The loss of glypican-3 induces alterations in Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2116–2125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindner JR, et al. The Drosophila Perlecan gene trol regulates multiple signaling pathways in different developmental contexts. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 2008;9:224. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esko JD, Zhang L. Influence of core protein sequence on glycosaminoglycan assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:663–670. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.David G, Bai XM, Van der Schueren B, Cassiman JJ, Van den Berghe H. Developmental changes in heparan sulfate expression: In situ detection with mAbs. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:961–975. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giráldez AJ, Copley RR, Cohen SM. HSPG modification by the secreted enzyme Notum shapes the Wingless morphogen gradient. Dev Cell. 2002;2:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreuger J, Perez L, Giraldez AJ, Cohen SM. Opposing activities of Dally-like glypican at high and low levels of Wingless morphogen activity. Dev Cell. 2004;7:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez AD, et al. OCI-5/GPC3, a glypican encoded by a gene that is mutated in the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome, induces apoptosis in a cell line-specific manner. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1407–1414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleeff J, et al. The cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan glypican-1 regulates growth factor action in pancreatic carcinoma cells and is overexpressed in human pancreatic cancer. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1662–1673. doi: 10.1172/JCI4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosaka M, et al. Arg-X-Lys/Arg-Arg motif as a signal for precursor cleavage catalyzed by furin within the constitutive secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12127–12130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter JA, et al. The product of hedgehog autoproteolytic cleavage active in local and long-range signalling. Nature. 1995;374:363–366. doi: 10.1038/374363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JJ, et al. Autoproteolysis in hedgehog protein biogenesis. Science. 1994;266:1528–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.7985023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLellan JS, et al. The mode of Hedgehog binding to Ihog homologues is not conserved across different phyla. Nature. 2008;455:979–983. doi: 10.1038/nature07358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azpiazu N, Lawrence PA, Vincent JP, Frasch M. Segmentation and specification of the Drosophila mesoderm. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3183–3194. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capurro MI, et al. Glypican-3 inhibits Hedgehog signaling during development by competing with patched for Hedgehog binding. Dev Cell. 2008;14:700–711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vyas N, et al. Nanoscale organization of hedgehog is essential for long-range signaling. Cell. 2008;133:1214–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veugelers M, et al. Glypican-6, a new member of the glypican family of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26968–26977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ybot-Gonzalez P, Copp AJ, Greene ND. Expression pattern of glypican-4 suggests multiple roles during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1013–1017. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos-Xavier AB, et al. Mutations in the heparan-sulfate proteoglycan glypican 6 (GPC6) impair endochondral ossification and cause recessive omodysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:760–770. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long F, Zhang XM, Karp S, Yang Y, McMahon AP. Genetic manipulation of hedgehog signaling in the endochondral skeleton reveals a direct role in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation. Development. 2001;128:5099–5108. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neri G, Gurrieri F, Zanni G, Lin A. Clinical and molecular aspects of the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:279–283. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981002)79:4<279::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cano-Gauci DF, et al. Glypican-3-deficient mice exhibit developmental overgrowth and some of the abnormalities typical of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:255–264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiao E, et al. Overgrowth of a mouse model of the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome is independent of IGF signaling. Dev Biol. 2002;243:185–206. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lum L, et al. Hedgehog signal transduction via Smoothened association with a cytoplasmic complex scaffolded by the atypical kinesin, Costal-2. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.