Abstract

Objective: To determine whether the excess mortality observed in patients who received both levodopa and selegiline in a randomised trial could be explained by revised diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, autonomic or cardiovascular effects, more rapid disease progression, or drug interactions.

Design: Open randomised trial and blind comparison and reclassification of the cause of death of patients who were recruited from 93 hospitals between 1985 and 1990 and who had died before December 1993 in arms 1 and 2.

Setting: United Kingdom.

Subjects: 624 patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were not receiving dopaminergic treatment and a subgroup of 120 patients who died during the trial.

Interventions: Levodopa and a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (arm 1), levodopa and a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor in combination with selegiline (arm 2), or bromocriptine alone (arm 3).

Main outcome measures: All cause mortality for 520 subjects in arms 1 and 2 and for 104 subjects who were randomised into these arms from arm 3. Cause specific mortality for people who died in the original arms 1 and 2 on the basis of the opinion of a panel, revised diagnosis and disability ratings, evidence from clinical records of either autonomic or cardiovascular episodes, other clinical features before death, and drug interactions.

Results: After extended follow up (mean 6.8 years) until the end of September 1995, when arm 2 was terminated, the hazard ratio for arm 2 compared with arm 1 was 1.32 (95% confidence interval 0.98 to 1.79). For subjects who were randomised from arm 3 the hazard ratio for arm 2 was 1.54 (0.83 to 2.87). When all subjects were included the hazard ratio was 1.33 (1.02 to 1.74) and after adjustment for other baseline factors it was 1.30 (0.99 to 1.72). The excess mortality seemed to be greatest in the third and fourth year of follow up. Cause specific death rates showed an excess of deaths from Parkinson’s disease only (hazard ratio 2.5 (1.3 to 4.7)). No significant differences were found for revised diagnosis, disability rating scores, autonomic or cardiovascular events, other clinical features, or drug interactions. Patients who died in arm 2 were more likely to have had possible dementia and a history of falls before death compared with those who died in arm 1.

Conclusion: The results consistently show excess mortality in patients treated with combined levodopa and selegiline. Revised diagnosis, autonomic or cardiovascular events, or drug interactions could not explain this finding, but falls and possible dementia were more common in arm 2. The results do not support combined treatment in patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. In more advanced disease, combined treatment should perhaps be avoided in patients with postural hypotension, frequent falls, confusion, or dementia.

Key messages

New data from the trial of the Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom still show higher death rates in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease treated with combined selegiline and levodopa compared with those treated with levodopa alone

No specific cause, other than Parkinson’s disease, could be found for this excess mortality

Combined selegiline and levodopa treatment seems to offer no advantage to patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease

In advanced Parkinson’s disease, selegiline may help manage symptoms but is best avoided in patients with postural hypotension, frequent falls, confusion, and dementia

Introduction

The Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom reported increased mortality in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease who were randomly allocated combined levodopa and selegiline treatment (arm 2) compared with levodopa alone (arm 1).1 Relative mortality was increased by about 60%, equivalent to one excess death for every 54 patients treated for 1 year. No clinically important differences in disability ratings were noted after either 12 or 4 years.1 These results were unexpected as selegiline was thought to protect against nigral cell death,3 to slow disease progression,4 and to reduce death rates.5

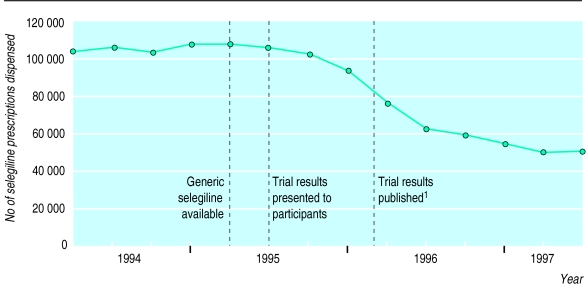

This trial has generated much controversy about the role of selegiline in the management of Parkinson’s disease. The number of selegiline prescriptions has almost halved in the United Kingdom since the findings of the trial were published (fig 1). Objections about the validity of the findings include inconsistency with other studies, the inappropriate use of an intention to treat analysis, lack of adjustment of results for early termination of arm 2, overall death rates being too high, the unreliability of death certification, and the possibility of differential misdiagnosis.6–9

Figure 1.

Quarterly tracking data for selegiline prescriptions dispensed in United Kingdom before and after publication of results of Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom.1 Source: Scriptcount (Taylor Nelson AGB)—volume of prescriptions dispensed based on representative sample of 300 pharmacies projected to give total for United Kingdom

Despite many of these criticisms being addressed,10,11 the reason for the excess mortality remains unclear. One suggested mechanism was that selegiline might increase the risk of a disturbance of cardiac rhythm or compromise the cardiovascular system through orthostatic hypotension.1 Other possibilities are that combination treatment may have accelerated nigral cell death or that selegiline may have had an adverse drug interaction with a drug not included in the trial.

We report updated and new death rates in subjects in arms 1 and 2 and in those who were randomised from arm 3 (bromocriptine) to arms 1 or 2. Results are also presented from the cause of death inquiry study, which reviewed the clinical course, cause of death, and circumstances around the time of death for all participants who died before December 1993.

Subjects and methods

The trial methods have been reported.1,2 Briefly, 782 patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease were randomly allocated to one of three treatment arms: levodopa and a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor alone (arm 1); levodopa, a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor, and selegiline (arm 2); and bromocriptine alone (arm 3). If a patient could not tolerate the drugs or showed little functional improvement they could be rerandomised to one of the other two arms. The principal outcomes were mortality and disability ratings. After an interim analysis of deaths up to December 1993 it was decided to terminate arm 2; patients were informed of this in October 1995.

The clinical record of every death before December 1993 was obtained from the relevant consultant, general practitioner, or nursing home. The records were systematically examined by JO, who recorded all drug treatment before death and deleted any references to antiparkinsonian drugs to conceal the trial arm. Data on severity of the disease within 3 months of death, comorbidity within 1 month of death, mobility within 1 month of death, and mode of death were recorded by AC on a standardised form.

A clinical summary of the clinical course, atypical clinical features, and comorbid medical conditions and a detailed résumé of events around the terminal illness was produced. Details of special investigations such as radiography and pathological and postmortem examination were included when available, but there was no access to the cause of death from the death certificate. A panel comprising a neurologist (AJL), geriatrician (PO), general practitioner (BH), and clinical epidemiologist (YB-S) reviewed each summary and assigned a cause of death according to ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision).12 The panel was blind to the death certificate and trial arm. Parkinson’s disease was coded as the underlying cause of death if it contributed to the death because of severe debility.

The panel rated diagnostic certainty for the cause of death from 1 (confident) to 5 (guessing)13 and determined whether the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease might have been incorrect and whether the patient might have had dementia.

The reliability of the panel was ascertained by presenting again 20 cases selected at random and stratified on confidence rating at least 3 months later. This was to maximise the likelihood that the cases had been forgotten. Cause specific mortality rates were recalculated using the panel’s classification to ascertain whether this altered the results based on death certificates in the previous report.1 When the panel was unable to reach a diagnosis the cause was taken from the death certificate.

Statistical analysis

The death rates in arms 1 and 2 were compared using the log rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The relative mortality hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Cox’s proportional hazards model, which enabled adjustment for possible prognostic factors. The adequacy of the proportional hazards model was tested using a log-time interaction with treatment group to check whether the hazard ratio changed with follow up.14

Codes for specific causes were grouped under the standard classification headings except for the more common conditions such as ischaemic heart disease (410-414) and cerebrovascular disease (430-438). Comparison of categorical and continuous variables were analysed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables.

Results

Mortality

Our previous paper reported the results of the interim analysis of December 1994.1 This analysis included deaths only before the end of 1993 because of the delay in notification of deaths from the NHS central register. This report provides data on mortality up to the end of September 1995, when arm 2 was terminated, providing an additional 21 months of follow up (average 6.8 years) and new results on 104 patients randomised from the bromocriptine arm to either arm 1 (53 patients) or 2 (51 patients).

Death rates were similar in arms 1 and 2 during the additional follow up (table 1). They were higher in patients who were rerandomised to arm 2 (levodopa and selegiline) than in those rerandomised to arm 1 (levodopa alone) (hazard ratio 1.54 (95% confidence interval 0.83 to 2.87)). The overall hazard ratio for mortality in arm 2 (levodopa and selegiline) compared with arm 1 (levodopa alone) when subjects who had been randomised a second time were included was 1.33 (1.02 to 1.74) (P=0.038 in log rank test); this was little altered when subjects who had been rerandomised were excluded. The confidence intervals have not been adjusted to take account of the early termination of arm 2; the inclusion of additional information means that this updated result is much less affected by the decision to stop treatment early. After adjustment for other baseline factors—age, sex, duration of Parkinson’s disease, disability before treatment, year of entry to trial—the hazard ratio was 1.30 (0.99 to 1.72). Analysis based on patients receiving treatment (“on treatment analysis”) gave a hazard ratio of 1.39 (0.94 to 2.05).

Table 1.

Numbers of deaths (person years) and hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) in patients treated with levodopa and selegiline (arm 2) and levodopa alone (arm 1)

| Variable |

Deaths (person years)

|

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 | Arm 2 | ||

| Deaths before 1994 (previously reported)1 | 44 (1372.6) | 76 (1500.5) | 1.57 (1.09 to 2.30) |

| Deaths during additional follow up to end of September 1995 | 29 (336.6) | 27 (334.3) | 1.05 (0.60 to 1.86) |

| All deaths to end of September 1995 | 73 (1709.2) | 103 (1834.8) | 1.32 (0.98 to 1.79) |

| Patients randomised from arm 3 | 21 (368.0) | 21 (280.5) | 1.54 (0.83 to 2,87) |

| All patients including those rerandomised | 94 (2077.2) | 124 (2115.3) | 1.33 (1.02 to 1.74) |

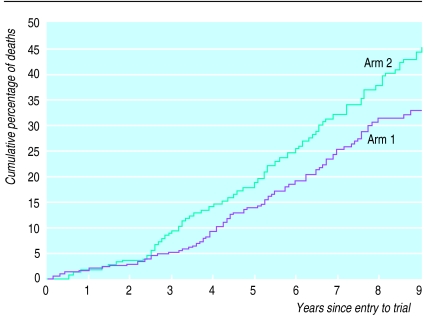

Figure 2 shows the updated Kaplan-Meier curve. Although a test of departure from the assumption of proportional hazards was not significant, the excess mortality was greatest in the third and fourth years of follow up and was more apparent for the on treatment analysis (table 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative percentage of deaths by treatment arm (Kaplan-Meier estimate). All patients randomly allocated to arms 1 and 2, including those randomised from arm 3. Numbers of patients surviving from years 1 to 9 were 294, 290, 282, 270, 254, 200, 146, 98, and 73 (arm 1); 317, 310, 291, 274, 258, 210, 140, 98, and 66 (arm 2)

Table 2.

Hazard ratios by duration of follow up in on treatment and intention to treat analyses

| Months after randomisation | Treatment arm | On treatment analysis

|

Intention to treat analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of deaths | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | No of deaths | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| -24 | 1 | 9 | 1.09 (0.45 to 2.69) | 9 | 1.35 (0.58 to 3.15) |

| 2 | 10 | 13 | |||

| 25-48 | 1 | 10 | 2.36 (1.14 to 4.92) | 21 | 1.79 (1.06 to 3.05) |

| 2 | 25 | 39 | |||

| >48 | 1 | 23 | 1.09 (0.63 to 1.88) | 64 | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.64) |

| 2 | 30 | 72 | |||

| All | 1 | 42 | 1.39 (0.94 to 2.05) | 94 | 1.33 (1.02 to 1.74) |

| 2 | 65 | 124 | |||

All patients randomly allocated to arms 1 and 2, including those randomised from arm 3.

As entry to the trial stopped in September 1990, information on mortality was complete for the first 5 years of follow up, so the results for the first 5 years were unaffected by the early termination of arm 2. The hazard ratio for the first 5 years for arm 2 compared with arm 1 was 1.38 (0.95 to 2.04).

Cause of death

Up to December 1993, 120 patients died (44/249 (17.7%) in arm 1 and 76/271 (28.0%) in arm 2). Twenty four cases had information from a postmortem examination. As information was not available for 21 cases because notes had been destroyed or lost, we relied only on information from the trial assessments, which may not have had information about the terminal event. The kappa coefficient15 for the 20 cases classified by the panel on the two occasions was 0.76 for the underlying cause of death, 0.73 for the confidence rating, and 1.0 for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (kappa >0.75, excellent; 0.40 to 0.75, fair to good; >0.40, poor). The panel reached a diagnosis in 90 cases. It decided that information was insufficient for the remaining 30 cases to be certain of the cause of death. The pattern of cause specific mortality based on the panel’s classification was similar to that previously reported (table 3). Only Parkinson’s disease showed an excess of deaths (hazard ratio 2.50 (1.32 to 4.73), whereas for other causes combined the hazard ratio was 1.21 (0.76 to 1.93).

Table 3.

Causes of death and death rates as classed by panel in comparison with cause given on death certificate

| Cause of death on certificate

|

Mortality per 1000 patients years (No of deaths)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same | Different | Arm 1 | Arm 2 | |

| Panel’s opinion | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | 30* | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 13 | 6 | 9.5 (13) | 6.7 (10) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 | 3 | 2.2 (3) | 6.0 (9) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 1 | 3 | 2.2 (3) | 3.3 (5) |

| Cancer | 11 | 0 | 4.4 (6) | 6.0 (9) |

| Parkinsonian syndrome | 19 | 15 | 9.5 (13) | 23.3 (35) |

| Respiratory disease | 2 | 2 | 2.2 (3) | 1.3 (2) |

| Other | 2 | 6 | 2.2 (3) | 4.0 (6) |

| All causes | 55 | 35 | 32.1 (44) | 50.7 (76) |

When panel could not reach diagnosis, cause from death certificate was used for calculating mortality.

When arms 1 and 2 were compared there were no significant differences between any of the clinical features and the mode of death (table 4). Patients in arm 2 were more likely to have possible dementia, and within three months of death they were more likely to have falls, postural dizziness, and shortness of breath. However, the proportion of cases with a revised diagnosis—for example, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and cerebrovascular disease—was slightly greater in arm 1.

Table 4.

Results from the cause of death inquiry study on clinical features before and at the time of death

| Clinical feature | No (%) of patients Arm 1 (n=44) | Arm 2 (n=76) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Probable Parkinson’s disease | 37 (84.1) | 68 (89.5) | –5.4 (–18.2 to 7.4) |

| Features 1 month before death | |||

| Angina, myocardial infarction | 6 (13.6) | 8 (10.5) | 3.1 (–9.2 to 14.4) |

| Heart failure | 7 (15.9) | 12 (15.8) | 0.1 (–13.4 to 13.7) |

| Bedbound | 11 (25.0) | 22 (28.9) | –4.0 (–20.3 to 12.4) |

| Faints | 4 (9.1) | 4 (5.3) | 3.8 (–6.0 to 13.7) |

| Postural dizziness | 2 (4.6) | 8 (10.5) | –6.0 (–15.2 to 3.3) |

| Postural hypotension | 4 (9.1) | 9 (11.8) | –2.3 (–13.9 to 8.4) |

| Supine hypotension | 7 (15.9) | 12 (15.8) | 0.1 (–13.4 to 13.7) |

| Shortness of breath | 6 (13.6) | 17 (22.4) | –8.7 (–22.5 to 5.1) |

| Falls* | 7 (15.9) | 19 (25.0) | –9.1 (–23.6 to 5.5) |

| Other drug treatment 3 months before death | |||

| Cardiac drugs | 22 (50.0) | 34 (44.7) | 5.3 (–13.3 to 23.8) |

| Antidepressants | 13 (29.5) | 17 (22.4) | 7.2 (–9.2 to 23.6) |

| Features at time of death | |||

| Died during day | 13 (29.5) | 22 (28.9) | 0.6 (–16.3 to 17.5) |

| Died at home | 8 (18.2) | 11 (14.5) | 3.7 (–10.2 to 17.6) |

| Sudden death | 7 (15.9) | 18 (23.7) | –7.8 (–22.2 to 6.7) |

| Unexpected death | 7 (15.9) | 11 (14.5) | 1.4 (–12 to 14.8) |

| Postmortem examination | 10 (22.7) | 14 (18.4) | 4.3 (–10.8 to 19.4) |

| Witnessed | 24 (54.5) | 42 (55.3) | –0.7 (–19.2 to 17.8) |

| Panel coding | |||

| Possible dementia | 9 (20.5) | 23 (30.3) | –9.8 (–25.6 to 6.0) |

| Uncertain cause | 11 (25.0) | 18 (23.7) | 1.3 (–14.7 to 17.3) |

Within 3 months of death.

The mean confidence score was slightly worse in arm 2 (3.00 v 2.59, P=0.19) and the postmortem rate was slightly lower. In arm 2 more deaths were classified as sudden, but the proportion of unexpected deaths and the proportion of deaths that occurred at home were similar. There was no evidence that patients in arm 2 had greater cardiovascular comorbidity as assessed by clinical disease or cardiac drugs, and patients in arm 2 were less likely to be taking antidepressants before death.

Disability subscales

Previous analyses showed that progression of disability was similar in the two treatment groups. As this contrasts with the excess mortality from Parkinson’s disease seen in arm 2, we examined this further by analysing the disability rating before death (table 5). There were no significant differences in any of the subscales between the two arms. Fifty two per cent of the disability ratings (91/176) were made within the year preceding death, 20% (35/176) within 1-2 years before death, and 28% (50/176) more than 2 years before death. This distribution was similar for arms 1 and 2.

Table 5.

Average disability scores by treatment arm based on last disability rating before death for 176 patients who died among those originally randomised to arms 1 and 2

| Arm 1 (n=73) | Arm 2 (n=103) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hoehn and Yahr score | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| North Western University disability subscales* | ||

| Walking | 6.2 | 6.9 |

| Dressing | 6.7 | 6.9 |

| Hygiene | 6.2 | 6.8 |

| Eating and feeding | 7.3 | 7.5 |

| Speech | 7.4 | 7.8 |

| Total | 33.8 | 35.8 |

| Webster subscales‡ | ||

| Bradykinesia of hands | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Rigidity | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Posture | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Upper extremity swing | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Gait | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| Tremor | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Facies | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Seborrhoea | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Speech | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Self care | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Balance | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Rising from chair | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Total | 16.4 | 15.5 |

Scored from 0 to 10, where 10=normal.

Scored from 0 to 3, where 0=normal.

Drugs

Ascertainment of the type of drugs taken around the time of death is important if the excess mortality observed with selegiline and levodopa is due to some acute toxic mechanism. We obtained drug information on 91 of the 120 patients who died, which was similar for arm 1 (31/44 (71%)) and arm 2 (60/76 (79%)) Almost all of the patients were taking levodopa 3 months before death (arm 1, 30/31 (97%); arm 2, 59/60 (98%)). In contrast, 23% (7/31) of the patients in arm 1 were no longer in the arm of treatment to which they had been randomised compared with 87% (52/60) taking selegiline in arm 2.

Discussion

The updated results show a relatively increased mortality for the combined levodopa and selegiline treatment compared with treatment with levodopa alone of around 35%, equivalent to one excess death per 75 patients treated for 1 year. The mortality ratios were remarkably consistent regardless of whether all deaths, deaths of patients who were rerandomised, or deaths in the first 5 years were considered. These estimates are lower than previously reported1 and are more realistic, as the previous result was based on an interim analysis. Although our confidence intervals are comparatively narrow, they are all around unity so that some results are significant while others are not. Had arm 2 of the trial continued, it is possible that the mortality would have diminished further, and both previous and current results could simply reflect chance. However, the similarity of the size of the effect in patients rerandomised from arm 3 provides an independent replication of the findings seen for the main group allocated to arms 1 and 2. Whereas subjects withdrawn from arm 3 may be unrepresentative, the randomisation process ensures that the internal comparison is valid and can be viewed as a separate trial. In addition, the complete mortality results based on the first 5 years of follow up were not affected by the decision to terminate arm 2 of the trial and so are less likely to represent a random high value.

We emphasise that this trial fails to support the hope that combined treatment might be associated with reduced mortality or improvement in disability rating scales. Unfortunately, no data were collected on quality of life or mood, so we cannot comment on whether combined treatment may have benefited these measures.

Possible explanations

One problem with the observed excess mortality is the lack of a clear reason for this observation. Other conditions which mimic Parkinson’s disease are difficult to diagnose as atypical features often develop only after several years16 and they have a worse prognosis than Parkinson’s disease.17,18 We did not, however, find a higher rate of revised diagnosis in arm 2 compared with arm 1 (11% v 15%). Another criticism was that an intention to treat analysis was inappropriate because of the comparatively large number of patients who withdrew.9 Ideally, we would like to have had accurate drug data on all of the patients, including those who withdrew at the time arm 2 was terminated. For the subgroup of patients who died for whom data were available, most patients in arm 2 were still receiving combined treatment while only a fifth of patients in arm 1 had selegiline added to their drug regimen before they died.

Since the original publication two studies have shown that selegiline diminishes autonomic responsiveness and increases risk of orthostatic hypotension.19,20 We postulated that if this mechanism was clinically important we should observe more sudden or unexpected deaths, hypotensive episodes, falls, and possibly a higher postmortem rate in arm 2. Our findings provide limited support for this hypothesis, though none of the differences were significant. However, retrospective analysis of clinical notes is likely to significantly underestimate the true rate of any hypotensive effect of selegiline and levodopa. The most marked difference in clinical characteristics between the two arms was for falls before death and possible dementia. Falls commonly occur among patients with severe Parkinson’s disease because of postural instability and akinesia as well as any autonomic effect. A randomised controlled trial of selegiline, α tocopherol, or placebo for Alzheimer’s disease noted a significant increase in falls and syncope in patients receiving selegiline in combination with α tocopherol.21

Dementia is not uncommon in association with Parkinson’s disease and is a poor prognostic factor.22,23 Selegiline and levodopa treatment may directly result in increased confusion. Alternatively, dementia may be a marker for general frailty and increased risk of adverse drug effects.24

One explanation could be that selegiline and levodopa contribute to hypotensive episodes which increase the risk of either a heart attack or stroke, especially in elderly patients with pre-existing atherosclerotic disease. However, both our analyses of cause specific mortality and of comorbidity did not support this notion. If combined treatment actually accelerated disease progression, and hence death from Parkinson’s disease, subjects in arm 2 would be expected to have worse disability scores and to be more disabled or bedbound before death. The data do not, however, support this hypothesis either. The use of cardiac or antidepressant drugs was no greater in arm 2 than arm 1, although we cannot rule out the possibility of a drug interaction because some of the patients’ records were destroyed.

One remaining possibility is that combined treatment is harmful to a subgroup of patients. This might explain why the greatest comparative mortality ratio was seen for the analysis of patients on allocated treatment between 2 and 4 years. If susceptible subjects are selectively removed from arm 2 the mortality ratios would be expected to return to unity with further follow up because only non-susceptible subjects would then remain in the study.

Clinical implications

Despite uncertainties there are some clear clinical implications from these results. There is no evidence that combined treatment with levodopa and selegiline confers advantages over levodopa treatment alone in terms of mortality or morbidity in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease. There seems little logic in giving patients with newly diagnosed disease combined treatment, although treatment might be started with selegiline alone and then withdrawn if levodopa treatment was indicated. Clinicians should determine whether the addition of selegiline for severely disabled patientd provides additional symptomatic benefit. In these patients quality of life is generally more important than quantity of life, and each case should be reviewed on its merits. However, if patients have clinically significant orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, confusional states, hallucinations, or deteriorating cognitive function, gradual and slow withdrawal of selegiline over 4 to 6 weeks should be seriously considered.

Acknowledgments

Members of the Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom who recruited subjects and followed up patients for the trial: R Abbott, N Banerji, M Barrie, G Boddie, P Bradbury, C Clarke, R Clifford-Jones, R Corston, E Critchley, P Critchley, R Cull, J Dick, I Draper, C Ellis, G Elrington, L Findley, T Fowler, J Frankel, A Gale, C Gardner-Thorpe, W Gibb, J D Gibson, J M Gibson, R Godwin-Austen, R Greenwood, R Hardie, D Harley, C Hawkes, S Hawkins, M Hildick-Smith, R Hughes, L Illis, J Jestico, K Kafetz, R Kapoor, C Kennard, R Knight, R Kocen, A Lees, N Leigh, L Loizou, R Lenton, D MacMahon, C D Marsden, W Michael, J Mitchell, P Monro, P Murdoch, W Mutch, P Overstall, D Park, J D Parkes, B Pentland, G D Perkin, R Ponsford, N Quinn, M Rawson, J Rees, M Rice-Oxley, D Riddoch, F Schon, A Schapira, D Shepherd, G Stern, B Summers, C Turnbull, A Turner, S Vakil, C Ward, A Whiteley, A Williams.

Editorials by Beteler and Abrams

Footnotes

Funding: Continued support from the Parkinson’s Disease Society of the United Kingdom, which also provided additional funding for the cause of death study, and Roche Products. Unconditional sponsorship from Britannia Pharmaceuticals and Sandoz Products.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Lees AJ.on behalf of the Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom. Comparison of therapeutic effects and mortality data of levodopa and levodopa combined with selegiline in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease BMJ 19953111602–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom. Comparisons of therapeutic effects of levodopa, levodopa and selegiline, and bromocriptine in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease: three years interim report. BMJ. 1993;307:469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6902.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tatton WG, Greenwood CE. Rescue of dying neurones: a new action for deprenyl in MPTP parkinsonism. J Neurol Sci. 1991;30:666–672. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkinson Study Group. Effect of deprenyl on the progression of disability in early Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1364–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911163212004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkmayer W, Knoll J, Riederer P, Youdim MBH, Hars V, Marton J. Increased life expectancy resulting from addition of l-deprenyl to Madopar treatment in Parkinson’s disease: a long-term study. J Neural Transm. 1985;64:113–127. doi: 10.1007/BF01245973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olanow CW, Fahn S, Langston JW, Godbold J. Selegiline and mortality in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:841–845. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva M, Watts P, Jenner P. Effect of adding selegiline to levodopa in early, mild Parkinson’s disease: Parkinson’s disease is rarely a primary cause of death. BMJ. 1996;312:703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7032.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jellinger KA. Effect of adding selegiline to levodopa in early, mild Parkinson’s disease: causes of death need confirmation. BMJ. 1996;312:704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7032.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerlach M, Riederer P, Vogt H. Effect of adding selegiline to levodopa in early, mild Parkinson’s disease: ‘on treatment’ rather than intention to treat analysis should have been used. BMJ. 1996;312:704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lees AJ, Head J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Effect of adding selegiline to levodopa in early, mild Parkinson’s disease. BMJ. 1996;312:704–705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7032.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees AJ, Head J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Selegiline and mortality in Parkinson’s disease: another view. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:282–283. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation. Manual of the international classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death, 9th revision. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alderson MR, Meade TW. Accuracy of diagnosis on death certificates compared with that in hospital records. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1967;21:22–29. doi: 10.1136/jech.21.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleiss JL. The measurement of interrater agreement. In: Fleiss JL, editor. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, 1st ed. New York: Wiley; 1981. pp. 212–236. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajput AH, Rozdilsky B, Rajput A. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis in parkinsonism—a prospective study. Can J Neurol Sci. 1991;18:275–278. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100031814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenning GK, Ben-Shlomo Y, Magalhes M, Daniel SE, Quinn NP. Clinical features and natural history of multiple system atrophy: an analysis of 100 cases. Brain. 1994;117:835–845. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvan I, Mangone CA, McKee A, Verny M, Parsa A, Jellinger K, et al. Natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) and clinical predictors of survival: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1996;60:615–620. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.6.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkka J, Suominen K, Tolonen U, Sotaniemi K, Myllyla VV. Selegiline diminishes cardiovascular autonomic responses in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48:662–667. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Churchyard A, Matthias CJ, Boonhongchuen P, Lees AJ. Autonomic effects of selegiline: possible cardiovascular toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:228–234. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, Klauber MR, Schafer K, Grundman M, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RG, Marsden CD. How common is dementia in Parkinson’s disease? Lancet. 1984;1:1262–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92807-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Shlomo Y, Whitehead AS, Davey Smith G. Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and motor neurone disease: clinical and pathological overlap may suggest common genetic and environmental factors. BMJ. 1996;312:724. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7033.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell AJ, Buchner DM. Unstable disability and the fluctuations of frailty. Age Ageing. 1997;26:315. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]