Abstract

Malaria therapy, experimental, and epidemiological studies have shown that erythrocyte Duffy blood group-negative people, largely of African ancestry, are resistant to erythrocyte Plasmodium vivax infection. These findings established a paradigm that the Duffy antigen is required for P. vivax erythrocyte invasion. P. vivax is endemic in Madagascar, where admixture of Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive populations of diverse ethnic backgrounds has occurred over 2 millennia. There, we investigated susceptibility to P. vivax blood-stage infection and disease in association with Duffy blood group polymorphism. Duffy blood group genotyping identified 72% Duffy-negative individuals (FY*BES/*BES) in community surveys conducted at eight sentinel sites. Flow cytometry and adsorption–elution results confirmed the absence of Duffy antigen expression on Duffy-negative erythrocytes. P. vivax PCR positivity was observed in 8.8% (42/476) of asymptomatic Duffy-negative people. Clinical vivax malaria was identified in Duffy-negative subjects with nine P. vivax monoinfections and eight mixed Plasmodium species infections that included P. vivax (4.9 and 4.4% of 183 participants, respectively). Microscopy examination of blood smears confirmed blood-stage development of P. vivax, including gametocytes. Genotyping of polymorphic surface and microsatellite markers suggested that multiple P. vivax strains were infecting Duffy-negative people. In Madagascar, P. vivax has broken through its dependence on the Duffy antigen for establishing human blood-stage infection and disease. Further studies are necessary to identify the parasite and host molecules that enable this Duffy-independent P. vivax invasion of human erythrocytes.

Keywords: erythrocyte, evolution, DARC, Madagascar

During malaria fever therapy trials, performed to treat neurosyphilis (1920s to 1960s) and in experimental field trials, it was consistently demonstrated that Africans and African-Americans were highly resistant to Plasmodium vivax blood-stage malaria when challenged with human blood or mosquitoes infected with limited numbers of P. vivax strains (1–3). Following identification of the Duffy blood group (Fy; reviewed in Zimmerman, 2004) (4), population studies showed that individuals of African ancestry expressed neither Fya nor Fyb antigens and were classified as Duffy negative, Fy(a−b−) (5). Following on observations that vivax malaria was rare in Africa (6), Miller et al. performed definitive in vivo studies to show that Duffy-negative people resisted, whereas Duffy-positive people were susceptible, to experimental P. vivax blood-stage infection following exposure to infected mosquitoes (7). This seminal work, and related Plasmodium knowlesi in vitro studies (7–9), established the paradigm that malaria parasites invade erythrocytes through specific “receptor”-based interactions and that the Duffy blood group was the receptor for P. vivax.

Resolution of molecular genetic factors responsible for Duffy blood group phenotypes has since been achieved. Erythrocyte Duffy negativity is explained by a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in a GATA-1 transcription factor binding site of the gene promoter (−33T → C) that governs erythroid expression (10). Variant antigens Fya, Fyb, and Fybweak are associated with SNPs in the gene’s coding region (11–14). Parallel studies identifying the P. vivax Duffy binding protein (PvDBP) (15–17) have provided the opportunity to dissect further the molecular interactions between parasite and host originally predicted by Miller (18, 19).

With the availability of molecular diagnostics, observations of P. vivax PCR-positive, Duffy-negative individuals have been made (20–22). PCR-positive samples have been reported in Brazil where there is significant admixture of Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive individuals (20, 21). However, the key biological evidence showing erythrocytes infected by P. vivax has not been provided. Indeed, PCR could potentially detect P. vivax merozoites released into the bloodstream by infected hepatocytes that are susceptible to the mosquito-transmitted sporozoites. Positive PCR is therefore not synonymous with presence of intraerythrocytic parasites. A recent Kenya-based study reported P. vivax-positive Anopheles mosquitoes within Duffy-negative populations and low density, microscopically positive blood smears in Duffy-negative children, which could not be confirmed (22). To follow these observations, a survey of >2,500 blood samples from West and central Africans living in nine malaria-endemic countries was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium ovale. Results found only one P. vivax-positive sample from a Duffy-positive individual and the authors concluded that low numbers of Duffy positives in Africa are sufficient to maintain P. vivax transmission (23). Thus, the question of P. vivax blood-stage infection of Duffy-negative individuals in areas where Duffy-positive and -negative populations are established remains open.

Madagascar, the world’s fourth largest island 250 miles off the East African coast, has been peopled by successive Austronesian and African migrations over the past 2,300 years (24, 25) (SI Appendix A, Figs. S1 and S2). There, potential exists for significant admixture among Duffy blood group phenotypes [Fy(a+b+), Fy(a+b−), Fy(a−b+), Fy(a−b−), Fy(a+bweak); nomenclature described in SI Appendix B, Table S1], providing Duffy-negative individuals consistent natural exposure to infection by P. vivax. In this island biogeographical context, where species are subjected to unique selective pressures, we investigated the relationship between Duffy blood group polymorphism and P. vivax blood-stage infection and clinical malaria.

Results

Duffy Genotyping and Plasmodium Species Diagnosis.

Among 2,112 asymptomatic school children seen at eight sites (February–April 2007), 709 were randomly selected. Of these, 382 (53.8%) children were self-identified to be of Asian origin, and 327 indicated they were of African origin. Both Duffy genotyping and Plasmodium species diagnostic assays were performed successfully for 661 children (Table S2). Overall, 72.0% (476/661) were genotyped as Duffy negative (FY*BES/*BES) and 28% (185/661) were Duffy positive (17.7% FY*A/*BES, 4.7% FY*B/*BES, 3.8% FY*A/*A, 1.7% FY*A/*B, and 0.1% FY*B/*B). Prevalence of each Plasmodium species was 16.2% P. falciparum, 13.0% P. vivax, 3.6% P. ovale, and 1.8% P. malariae; 5.2% of participants were infected with multiple species. Among Duffy-negative individuals 42 (8.8%) were P. vivax PCR positive based on the small subunit (SSU) rDNA assay, 32 of which were characterized as P. vivax monoinfections. All 42 P. vivax infections were confirmed by additional Plasmodium species PCR assays based on cytochrome oxidase I (COI) and/or PvDBP (SI Appendix C). P. vivax infection and Duffy genotype distribution among the school-age children are summarized in Fig. 1. Results show that the highest number of Duffy-negative individuals PCR positive for P. vivax were observed at Tsiroanomandidy (n = 30) and Miandrivazo (n = 9), study sites with the highest frequencies of Duffy-positive study participants (47.2 and 31.8%, respectively). Interestingly, in individual study sites with sufficient numbers of PCR-positive P. vivax infections to enable comparisons, prevalence ratios were not significantly different between Duffy-positive and -negative children (Tsiroanomandidy χ2, 1 df = 2.87, P = 0.09; Miandrivazo χ2, 1 df = 0.116, P = 0.733; Maevatanana χ2, 1 df = 1.18, P = 0.278). In contrast to these village-specific findings, when considering all 661 school children surveyed, Duffy-negatives were still 3-fold less likely to experience a P. vivax blood stage infection compared to Duffy-positive children (Odds ratio = 0.310, 95% confidence interval 0.195–0.493; P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of P. vivax infections and clinical cases identified in Duffy-positive and -negative Malagasy people. Pie graphs show the prevalence of Duffy-positive (dark/light green) and Duffy-negative (red/pink quadrants) phenotypes in the eight Madagascar study sites. Prevalence of P. vivax infection observed in the survey of school-age children is shown in red and dark green; population subsets not infected with P. vivax are pink and light green. Study sites identified by a red star indicate that clinical vivax malaria was observed in Duffy-negative individuals (additional data classify clinical cases as numbers of people diagnosed with monoinfection P. vivax/mixed P. vivax + P. falciparum). A green star indicates that vivax malaria was observed in Duffy-positive individuals only (Ejeda). In Ihosy clinical malaria was observed in one individual with a mixed P. vivax/P. falciparum infection. P. vivax malaria was not observed in Andapa and Farafangana (black star). Malaria transmission strata are identified as tropical (lightest gray), subdesert (light gray), equatorial (middle gray), and highlands (dark gray).

Intraerythrocytic P. vivax Infection and Clinical Malaria in Duffy Negatives.

One hundred eighty-three P. vivax-infected samples were collected in 2006/2007 from febrile individuals seeking malaria treatment from health facilities (26). Among these, 153 carried P. vivax monoinfections and 30 were P. vivax/P. falciparum mixed infections. Of the patients experiencing clinical malaria, 17 Duffy-negative individuals from five of the study sites (Fig. 1, red stars; Table S3) were P. vivax infected. Whereas 8 of these malaria patients were infected with P. vivax in the context of a mixture of Plasmodium species, 9 were judged to be infected with only P. vivax by combined conventional blood smear and PCR-based Plasmodium species diagnoses. With 5.9% (9/153) of clinical P. vivax monoinfection malaria experienced by Duffy negatives vs. 94.1% (144/153) by Duffy positives, Duffy negativity conferred a >15-fold reduction in prevalence to P. vivax malaria.

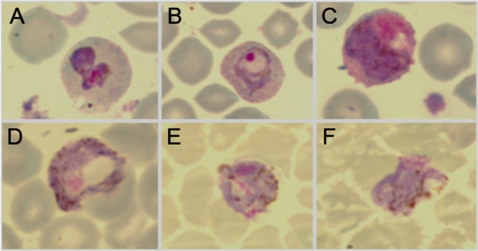

Standard blood smear microscopy showed evidence of intraerythrocytic infection in four individuals by examining Giemsa-stained slides (Fig. 2). Classic morphological features of P. vivax trophozoites (Fig. 2 A and B) and P. vivax gametocytes (Fig. 2 C–F) were observed. Results showing both male and female gametocytes within the same infection suggest that P. vivax transmission from Duffy-negative people is possible.

Fig. 2.

Standard Giemsa-stained thin smear preparations of P. vivax infection and development in human Duffy-negative erythrocytes. A–C originated from a 4-year-old female, genotyped as Duffy negative (FY*BES/*BES), who presented at the Tsiroanomandidy health center (June 26, 2006) with fever (37.8 °C), headache, and sweating without previous antimalarial treatment. Standard blood smear diagnosis revealed a mixed infection with P. vivax [parasitemia = 3,040 parasitized red blood cells (pRBC)/μL] and P. falciparum (parasitemia = 980 pRBC/μL). PCR-based Plasmodium species diagnosis confirmed the blood smear result; P. malariae and P. ovale were not detected. A shows an undifferentiated P. vivax trophozoite with enlarged erythrocyte volume, clear evidence of Schüffner stippling, and amoeboid morphology. B shows a P. vivax early stage trophozoite with condensed chromatin, enlarged erythrocyte volume, Schüffner stippling, and irregular ring-shaped cytoplasm. C shows a P. vivax gametocyte: Lavender parasite, larger pink chromatin mass, and brown pigment scattered throughout the cytoplasm are characteristics of microgametocytes (male). D originated from a 12-year-old Duffy-negative (FY*BES/*BES) male, who presented at the Miandrivazo health center (June 27, 2006) with fever (37.5 °C) and shivering without previous antimalarial treatment. Standard blood smear diagnosis and light microscopy revealed infection with only P. vivax (parasitemia = 3,000 pRBC/μL). PCR-based Plasmodium species diagnosis confirmed this blood smear result; P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale were not detected. The parasite featured shows evidence of a P. vivax gametocyte: Large blue parasite, smaller pink chromatin mass, and brown pigment scattered throughout the cytoplasm are characteristics of macrogametocytes (female). E and F originated from a 3-year-old Duffy-negative (FY*BES/*BES) female, who presented at the Moramanga health center (April 11, 2006) with fever (37.8 °C) without previous antimalarial treatment. Standard blood smear diagnosis and light microscopy revealed infection with only P. vivax (parasitemia = 3,368 pRBC/μL). PCR-based Plasmodium species diagnosis confirmed this blood smear result; P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale were not detected. The parasites featured show additional evidence of P. vivax gametocytes.

Erythrocyte Duffy-Negative Genotype and Phenotype Concordance.

Further evaluation of 43 Tsiroanomandidy school children was performed to confirm concordance between Duffy genotypes and phenotypes using conventional serology, flow cytometry, and adsorption–elution methods. Comparison of Duffy genotyping with serology was 100% concordant for all Duffy positive/negative and Fya/Fyb antigenic classifications. Fig. 3 illustrates flow cytometry phenotypes comparing control donors and field samples. Fig. 3A shows mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) that reflect binding of the Duffy antigen-specific anti-Fy6 antibody (NaM185-2C3) for well-characterized control donors who were FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)], FY*BES/*X [Fy(a−bweak)], FY*X/*X [Fy(a−bweak)], FY*A/*BES [Fy(a+b−)], and FY*A/*B [Fy(a+b+)], respectively. Additionally, Fig. 3A shows that flow cytometry results for one FY*BES/*BES Malagasy donor were identical to the West African FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)] control and the isotype background control, confirming no erythrocyte surface expression of the extracellular amino terminus of the protein known to mediate invasion of vivax merozoites. Fig. 3B shows results for 40 Malagasy individuals, with 30 samples genotyped FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)], 6 genotyped FY*A/*BES [Fy(a+b−)], 2 genotyped FY*A/*A [Fy(a+b−)], and 2 genotyped FY*A/*B [Fy(a+b+)]. Results show that Duffy antigen expression was uniformly absent from erythrocyte surfaces of all FY*BES/*BES individuals; flow cytometry phenotypes for the Duffy-positive donors showed expected patterns of anti-Fy6 antibody binding. To ascertain that ablated serological detection of Duffy was not due to a mutation in the epitope-coding sequence, >2,550 bp of the Duffy gene were sequenced for 14 Duffy-negative Malagasy study participants who had experienced P. vivax clinical malaria (included proximal promoter and full coding sequence; GenBank accession nos. GU130196 and GU130197). This sequencing showed identity between Duffy-negative Malagasy alleles and three West African FY*BES alleles and the FY*BES GenBank reference sequence (X85785) (10) and verified that failure to detect the Duffy antigen by serology resulted from the −33 T → C GATA-1 promoter mutation of the otherwise unaltered Duffy gene.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry and serological correlation of Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive phenotypes with respective genotypes in Malagasy school children from Tsiroanomandidy, Madagascar. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of Duffy blood group genotypes. Flow cytometry histograms show MFI that reflect binding of the Duffy antigen-specific anti-Fy6 antibody (NaM185-2C3) for one Malagasy genotyped as FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)] (red) and five well-characterized control donors who are FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)] (solid black), FY*BES/*X [Fy(a−bweak)] (light green), FY*X/*X [Fy(a−bweak)] (green), FY*A/*BES [Fy(a+b−)] (light blue), and FY*A/*B [Fy(a+b+)] (blue), respectively. Results include fluorescence of a Duffy-positive blood sample incubated with an isotype control antibody (dotted black line). (B) Flow cytometry of Duffy antigen expression on erythrocytes from 40 Malagasy study participants. Flow cytometry results show MFI that reflect binding of the Duffy antigen-specific anti-Fy6 antibody for 30 FY*BES/*BES [Fy(a−b−)] Malagasy samples (mean = 48, SD = 1.2), 6 FY*A/*BES [Fy(a+b−)] Malagasy samples (mean = 1,025, SD = 22.4), 2 FY*A/*A [Fy(a+b−)] Malagasy samples (mean = 1,937, SD = 54) and 2 FY*A/*B [Fy(a+b+)] Malagasy samples (mean = 1,896, SD = 8).

P. vivax Strains Infecting Duffy-Negative Malagasies.

To evaluate the diversity of P. vivax strains we analyzed the circumsporozoite protein (PvCSP) and P. vivax-specific microsatellites (27). Positive genotyping of 16 isolates for PvCSP showed the presence of both VK210 and VK247 variants (VK210, n = 6; VK247, n = 1; VK210 and VK247, n = 9). The mean Nei’s unbiased expected heterozygosity (He) estimated with microsatellite loci (6–13 alleles identified per infection) did not differ significantly between Duffy-positive (n = 45) and Duffy-negative (n = 11) patients (0.67 ± 0.17 vs. 0.74 ± 0.15, n = 11, P > 0.05); Wright’s fixation index analysis showed an absence of genetic differentiation between the two populations (Fst = 0.0094, P = 0.20). Results suggest that numerous strains are able to infect both Duffy-negative and -positive individuals.

Discussion

We studied P. vivax infection in Madagascar in an admixed human population that included Duffy-positive and -negative people to test whether consistent natural exposure may have provided P. vivax with sufficient opportunity to break through the Duffy-negative barrier thought to confer human resistance to P. vivax blood-stage infection. We observed eight different Duffy genotypes in the study population, including a high frequency of Duffy negativity (72%), and discovered that a considerable number of Duffy-negative Malagasies were susceptible to P. vivax blood-stage infection and clinical vivax malaria. Vivax malaria was most common in study sites where the prevalence of Duffy positivity was highest. Whereas we found that P. vivax PCR positivity did not differ between Duffy-positive and -negative people in high prevalence villages (Tsiroanomandidy and Miandrivazo), we observed a significant 3-fold reduction in P. vivax infection in Madagascar overall, and a substantial reduction in prevalence of clinical P. vivax malaria among Duffy negatives compared to Duffy positives. These findings suggest that P. vivax invasion of Duffy-negative erythrocytes may be somewhat impaired relative to invasion of Duffy-positive individuals, preventing development of higher parasitemia associated with clinical disease in many individuals.

Human settlement of Madagascar from populations participating in the Indian Ocean trade network beginning ≈2,000 years ago may have been responsible for introducing P. vivax into Madagascar by infected immigrants from Southeast Asia (SI Appendix A). Increase in human population density would have provided conditions to sustain P. vivax transmission. It is unlikely that P. vivax would cause blood-stage infection in Duffy negatives initially. However, a consistent supply of parasites available from infected Duffy-positive Malayo-Indonesians would have provided ample opportunity for infection of hepatocytes of Duffy negatives and selection of P. vivax strains with a new capacity for erythrocyte invasion. A report that the so-called Madagascar P. vivax strain (28) caused blood-stage infection in one Liberian individual (2) may provide evidence of unique P. vivax evolution in Madagascar consistent with our findings, although the Duffy phenotype of the susceptible Liberian was not established.

Whereas new combinations of mutations or altered gene expression could have resulted from population admixture and subsequent recombination between Duffy-negative and -positive alleles in the study participants, Duffy gene sequence analysis and flow cytometry results provide no evidence that a Duffy receptor is available on erythrocyte surfaces of genotypically Duffy-negative (FY*BES/*BES) Malagasies. Thus P. vivax strains infecting Duffy negatives in this study would have required a Duffy-independent mechanism for erythrocyte invasion.

Interestingly, observations of P. vivax infection of nonhuman primate erythrocytes and human infection by the related P. knowlesi may provide insight regarding an alternative invasion mechanism. P. vivax readily infects erythrocytes of the squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis) (29, 30). Whereas squirrel monkeys express an Fy6-positive Duffy antigen (29–31), the P. vivax DBP binds poorly, if at all, to squirrel monkey erythrocytes (32), suggesting a PvDBP-independent invasion mechanism. In vitro studies showing that P. knowlesi invades Duffy-negative erythrocytes treated with trypsin and neuraminidase (33) suggest that P. knowlesi possess additional erythrocyte invasion ligands enabling Duffy-independent blood-stage infection. Whether our results signal local evolution of a new P. vivax erythrocyte invasion pathway, or indicate the existence of yet-uncharacterized erythrocyte invasion mechanisms involving DBPs and/or reticulocyte binding proteins (34, 35), remains to be clarified.

With accumulating reports on severe P. vivax morbidity and mortality there is a growing appreciation that this parasite exerts considerable selective pressure on human health (36). Meanwhile, debate persists regarding the evolutionary relationship between P. vivax and Duffy negativity. Observations of P. vivax PCR positivity in Duffy-negative people add support for alternative receptors (20–22). In contrast, the observation that carriers of the Papua New Guinea Duffy-negative allele (FY*AES) (37) experience reduced P. vivax blood-stage infection (38) underscores the strong dependence this parasite displays on Duffy-dependent invasion.

Our observations in Madagascar showing conclusive evidence that P. vivax is capable of causing blood-stage infection and disease in Duffy-negative people illustrate that in some conditions P. vivax exhibits a capacity for infecting human erythrocytes without the Duffy antigen. The data assembled in this study suggest that conditions needed to clear the barrier of Duffy negativity may include an optimal human admixture. In Madagascar with significant numbers of Duffy-positive people and full susceptibility of hepatocytes in Duffy negatives, P. vivax may have sufficient exposure to Duffy-negative erythrocytes, allowing more opportunities for de novo selection or optimization of an otherwise cryptic invasion pathway that nevertheless seems less efficient than the Duffy-dependent pathway.

Finally, given our observations in Madagascar and those from South America and Kenya, a better understanding of the alternative pathways P. vivax uses to invade human erythrocytes should become a priority. As current P. vivax vaccine strategies focused on PvDBP attempt to exploit Duffy-dependent invasion (39), these collected findings emphasize the importance of a multivalent vaccine strategy that can reduce the potential for parasite strains to escape immunologic control focused on a single protein and a single erythrocyte invasion pathway.

Materials and Methods

Populations and Conventional Parasite Diagnosis.

Human subjects protocols (007/SANPF/2007 and 156/SANPFPS/2007) were approved by the Madagascar Ministry of Health, National Ethics Committee; genotyping was performed following a University Hospitals Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board protocol (08-03-33). A cross-sectional survey to evaluate erythrocyte polymorphisms associated with malaria susceptibility was conducted among Malagasy school children in 2007 (40). Children (3–13 years) were recruited at eight study sites, representing the four malaria epidemiological strata of Madagascar (SI Appendix A), using a two-level cluster random sampling method (school and classroom). After obtaining informed consent from parents/guardians, whole blood (5 mL) was collected (K+-EDTA Vacutainers) by venipuncture from each child. In March 2009 additional blood samples were collected from the same Tsiroanomandidy study population.

In vivo efficacy studies on antimalarial drugs were conducted in 2006 and 2007 at the eight study sites (registration no. ISRCTN36517335) (26, 27). P. vivax clinical samples, collected on filter paper, were selected from all patients screened by a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) (OptiMAL-IT; Diamed AG). Giemsa-stained thin/thick blood films were prepared for each RDT-positive patient to check both Plasmodium species identification and parasite densities. All patients enrolled in these studies were >6 months old, judged to be P. vivax positive with parasite densities ≥250/μL, and had a history of fever (axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C) 48 h before recruitment. Patients displaying mixed infections with P. vivax and P. falciparum were treated according to the new National Malaria Policy, with a combination of artesunate and amodiaquine (Arsucam) (41). An enrollment questionnaire administered to each patient included history of fever, prior treatment, age, gender, location of habitation, and ethnicity.

DNA Extraction.

DNA was extracted from blood spots with Instagene Matrix resin (BioRad) or directly from whole blood (100 μL) using proteinase K/phenol-chloroform.

Molecular Diagnosis.

Molecular diagnosis evaluating SNP (Duffy −33, promoter ±; codon 42, FY*A vs. FY*B) was performed using a post-PCR ligase detection reaction–fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) or direct sequencing of PCR products (SI Appendix C).

Plasmodium species identification from school children was performed using a PCR-based SSU rRNA assay (42). Asymptomatic P. vivax infections were confirmed for each Duffy-negative sample using PCR-based assays for COI and PvDBP. P. vivax population diversity was evaluated using PvCSP and microsatellite markers (27). Plasmodium species identification from clinical samples was performed using real-time (43) and classical PCR (44).

Duffy Phenotyping.

Duffy phenotyping was performed using fresh blood samples collected in March 2009. Duffy antigens (Fya/Fyb) were phenotyped using a microtyping kit and antisera (DiaMed-ID Microtyping System), following manufacturer’s instructions. Expression of Duffy antigen on erythrocytes was evaluated by flow cytometry (BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer; Becton Dickinson) using monoclonal antibodies: F655 antibody (Fya specific), Hiro31 antibody (Fyb specific), and anti-Fy6 antibody (NaM185-2C3 clone, Duffy specific) (45). Briefly, erythrocytes from EDTA-anticoagulated field and control samples [Fy(a+b−), Fy(a−b+), Fy(a+b+), and Fy(a−bweak); obtained from the Centre National de Reference pour les Groupes Sanguins, Paris] were washed twice in phosphate buffer solution (PBS). Cells were then resuspended with isotype controls IgG/IgM (5 μg/mL; BD) or monoclonal antibodies (anti-Fy6 diluted at 1:8, Hiro31 and F655 diluted at 1:4) at room temperature for 1 h in PBS/0.1% BSA solution. After primary incubation, cells were washed twice in PBS and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h with secondary phycoerythrin (PE) antibody (Beckman Coulter) at a concentration of 5 μg/mL in PBS/0.1% BSA solution. After a final wash in PBS, cells were acquired by a digital high speed analytical flow cytometer. Erythrocytes were identified on the basis of forward/side scatter characteristics, using logarithmic amplification. After excitation at 488 nm, PE signal was collected with a 585/42 band pass filter. Data were acquired by BD FACS Diva software (v6.1.2) and analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar) software v7.2.5. Final controls of erythrocyte Duffy antigen expression were performed using adsorption–elution experiments (14).

Population Genetic Analyses.

Genetic diversity was assessed by Nei's unbiased expected heterozygosity (He) from haploid data and calculated as He = [n/(n − 1)][1 −  ] (n is the number of isolates sampled; pi2 is the frequency of the ith allele) (46). Population genetic differentiation between symptomatic Duffy negatives and positives was measured using Wright's F statistics (47); population genetic parameters were computed with FSTAT software, v2.9.4 (48).

] (n is the number of isolates sampled; pi2 is the frequency of the ith allele) (46). Population genetic differentiation between symptomatic Duffy negatives and positives was measured using Wright's F statistics (47); population genetic parameters were computed with FSTAT software, v2.9.4 (48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the school children and their parents/guardians for participating in the study, administrative staff and teachers, and Circonscription Scolaire chiefs who helped us with study organization. We thank the patients and health care workers involved in the national network for malaria resistance surveillance in Madagascar (Réseau d'Etude de la Résistance) and staff of the Madagascar Ministry of Health. We thank L. Randrianasolo, R. Raherinjafy, A. Randriamanantena, H. Ranaivosoa, D. Ralaizandry, D. Raveloariseheno, V. Rabekotorina, R. Razakandrainibe, E. Rakotomalala, H. Andrianantenaina, O. Voahanginirina, T. Eugénie Rahasana, A. Contamin, and L. Fanazava for helping with field work. We especially thank B. Contamin (Fondation Mérieux, Lyon) and M. Noelle Ungeheuer (Clinical Investigation and Biomedical Research Support Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris). We thank Dr. B. N. Pham and E. Vera (Centre National de Référence pour les Groupes Sanguins) for frozen blood sample management and fixation/elution experiments and M. Tichit (Institut Pasteur, Paris) for DNA sequencing. This study was supported by the BioMalPar European Network of Excellence (LSHP-CT-2004-503578) from the Priority 1 “Life Sciences, Genomics and Biotechnology for Health” in the 6th Framework Programme, from Plate-forme Génomique (Génopôle, Institut Pasteur, Paris); by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AI46919 and TW007872); and by the Global Fund (MDG-304-G05-M) and Veterans' Affairs Research Service. C. Barnadas received postdoctoral fellowship support from Fondation Mérieux (Lyon, France). V. Thonier was supported by an “année-recherche” grant from the Direction des Affaires Sanitaires et Sociales of the Rhone Alpes.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. GU130196 and GU130197).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0912496107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boyd MF, Stratman-Thomas WK. Studies on benign tertian malaria. 4. On the refractoriness of negroes to inoculation with Plasmodium vivax. Am J Hyg. 1933;18:485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray RS. The susceptibility of Liberians to the Madagascar strain of Plasmodium vivax. J Parasitol. 1958;44(4, Sect 1):371–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Leary PA. Treatment of neurosyphilis by malaria: Report on the three years’ observation of the first one hundred patients treated. J Am Med Assoc. 1927;89:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman PA. In: Infectious Disease and Host-Pathogen Evolution. Dronamraju KR, editor. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2004. pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roychoudhury AK, Nei M. Human Polymorphic Genes: World Distribution. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escudie A, Hamon J. Malaria in French West Africa. Med Trop (Mars) 1961;21(Special):661–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller LH, et al. Evidence for differences in erythrocyte surface receptors for the malarial parasites, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium knowlesi. J Exp Med. 1977;146:277–281. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH, Rothman IK. Erythrocyte receptors for (Plasmodium knowlesi) malaria: Duffy blood group determinants. Science. 1975;189:561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1145213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tournamille C, Colin Y, Cartron JP, Le Van Kim C. Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;10:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwamoto S, Omi T, Kajii E, Ikemoto S. Genomic organization of the glycoprotein D gene: Duffy blood group Fya/Fyb alloantigen system is associated with a polymorphism at the 44-amino acid residue. Blood. 1995;85:622–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsson ML, et al. The Fy(x) phenotype is associated with a missense mutation in the Fy(b) allele predicting Arg89Cys in the Duffy glycoprotein. Br J Haematol. 1998;103:1184–1191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tournamille C, Le Van Kim C, Gane P, Cartron JP, Colin Y. Molecular basis and PCR-DNA typing of the Fya/fyb blood group polymorphism. Hum Genet. 1995;95:407–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00208965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tournamille C, et al. Arg89Cys substitution results in very low membrane expression of the Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines in Fy(x) individuals. Blood. 1998;92:2147–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams JH, et al. A family of erythrocyte binding proteins of malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7085–7089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang XD, Kaslow DC, Adams JH, Miller LH. Cloning of the Plasmodium vivax Duffy receptor. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;44:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wertheimer SP, Barnwell JW. Plasmodium vivax interaction with the human Duffy blood group glycoprotein: Identification of a parasite receptor-like protein. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:340–350. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hans D, et al. Mapping binding residues in the Plasmodium vivax domain that binds Duffy antigen during red cell invasion. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1423–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh SK, Hora R, Belrhali H, Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Structural basis for Duffy recognition by the malaria parasite Duffy-binding-like domain. Nature. 2006;439:741–744. doi: 10.1038/nature04443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavasini CE, et al. Duffy blood group gene polymorphisms among malaria vivax patients in four areas of the Brazilian Amazon region. Malar J. 2007;6:167. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavasini CE, et al. Plasmodium vivax infection among Duffy antigen-negative individuals from the Brazilian Amazon region: An exception? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1042–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan JR, et al. Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a duffy antigen negative population in Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Culleton RL, et al. Failure to detect Plasmodium vivax in West and Central Africa by PCR species typing. Malar J. 2008;7:174. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burney DA, et al. A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar. J Hum Evol. 2004;47:25–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurles ME, Sykes BC, Jobling MA, Forster P. The dual origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: Evidence from maternal and paternal lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:894–901. doi: 10.1086/430051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnadas C, et al. Plasmodium vivax resistance to chloroquine in Madagascar: Clinical efficacy and polymorphisms in pvmdr1 and pvcrt-o genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4233–4240. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00578-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnadas C, et al. Plasmodium vivax dhfr and dhps mutations in isolates from Madagascar and therapeutic response to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. Malar J. 2008;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shute PG, Garnham PCC, Maryon M. The Madagascar strain of Plasmodium vivax. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1980;47:173–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnwell JW, Nichols ME, Rubinstein P. In vitro evaluation of the role of the Duffy blood group in erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium vivax. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1795–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols ME, Rubinstein P, Barnwell J, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Rosenfield RE. A new human Duffy blood group specificity defined by a murine monoclonal antibody. Immunogenetics and association with susceptibility to Plasmodium vivax. J Exp Med. 1987;166:776–785. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.3.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tournamille C, et al. Sequence, evolution and ligand binding properties of mammalian Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:682–694. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0633-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran TM, et al. Detection of a Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte binding protein by flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2005;63:59–66. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason SJ, Miller LH, Shiroishi T, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH. The Duffy blood group determinants: Their role in the susceptibility of human and animal erythrocytes to Plasmodium knowlesi malaria. Br J Haematol. 1977;36:327–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1977.tb00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galinski MR, Medina CC, Ingravallo P, Barnwell JW. A reticulocyte-binding protein complex of Plasmodium vivax merozoites. Cell. 1992;69:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90642-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlton JM, et al. Comparative genomics of the neglected human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nature. 2008;455:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nature07327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baird JK. Resistance to therapies for infection by Plasmodium vivax. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:508–534. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmerman PA, et al. Emergence of FY*A(null) in a Plasmodium vivax-endemic region of Papua New Guinea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13973–13977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasehagen LJ, et al. Reduced Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte infection in PNG Duffy-negative heterozygotes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galinski MR, Barnwell JW. Plasmodium vivax: Who cares? Malar J. 2008;7(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Razakandrainibe R, et al. Epidemiological situation of malaria in Madagascar: Baseline data for monitoring the impact of malaria control programmes using serological markers. Acta Trop. 2009;111:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Programme National de Lutte contre le Paludisme . Politique Nationale de Lutte contre le Paludisme a Madagascar. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Ministère de la Santé et du Planning Familial; 2005. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNamara DT, Thomson JM, Kasehagen LJ, Zimmerman PA. Development of a multiplex PCR-ligase detection reaction assay for diagnosis of infection by the four parasite species causing malaria in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2403–2410. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2403-2410.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Monbrison F, Angei C, Staal A, Kaiser K, Picot S. Simultaneous identification of the four human Plasmodium species and quantification of Plasmodium DNA load in human blood by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:387–390. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh B, et al. A genus- and species-specific nested polymerase chain reaction malaria detection assay for epidemiologic studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:687–692. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasniowska K, et al. Structural characterization of the epitope recognized by the new anti-Fy6 monoclonal antibody NaM 185-2C3. Transfus Med. 2002;12:205–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2002.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89:583–590. doi: 10.1093/genetics/89.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright S. The interpretation of population structure by F-statistics with special regard to systems of mating. Evolution. 1965;19:395–420. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goudet J. Fstat (Version 2.9.4), a Program to Estimate and Test Population Genetics Parameters. 2003 Updated from Goudet (1995). Available from http://www.unil.ch/izea/softwares/fstat.html. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.