Abstract

At 2 years of age, 100% (23/23) of ERβ−/− female mice have developed large pituitary and ovarian tumors. The pituitary tumors are gonadotropin-positive and the ovarian tumors are sex cord (less differentiated) and granulosa cell tumors (differentiated and estrogen secreting). No male mice had pituitary tumors and no pituitary or ovarian tumors developed in ERα−/− mice or in ERαβ−/− double knockout mice. The tumors have high proliferation indices, are ERα-positive, ERβ-negative, and express high levels of nuclear phospho-SMAD3. Mice with granulosa cell tumors also had hyperproliferative endometria. The cause of the pituitary tumors appeared to be excessive secretion of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus resulting from high expression of NPY. The ovarian phenotype is similar to that seen in mice where inhibin is ablated. The data indicate that ERβ plays an important role in regulating GnRH secretion. We suggest that in the absence of ERβ, the proliferative action of FSH/SMAD3 is unopposed and the high proliferation leads to the development of ovarian tumors. The absence of tumors in the ERαβ−/− mice suggests that tumor development requires the presence of ERα.

Keywords: estrogen receptor β (ERβ), pituitary, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), TGFβ

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis regulates reproductive function (1). Estrogen plays numerous modulatory roles within all three components of the HPG axis including hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads and is necessary for maintenance of proper function of the HPG axis (2). In mammals, steroid hormones produced in the gonads are responsible for negative feedback on the HPG axis. In the pituitary, estrogen via ERα modulates release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (3–6).

Both estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ (7, 8), are expressed in the HPG axis, but each receptor has a distinct tissue expression pattern (9). Several studies have shown that in the rodent and human hypothalamus, the GnRH neurons express ERβ but not ERα (10, 11). ERβ appears to regulate the amount of GnRH secreted and lack of ERβ might lead to hyperstimulation of the pituitary (12, 13). In the anterior lobe of the pituitary, ERα is the predominant receptor and expression of ERβ is very low (14–16). In the ovary, ERα is the predominant receptor in interstitial and thecal cells, whereas ERβ is localized in the granulosa cells of growing follicles, which are the primary sites of FSH action and estradiol synthesis (17, 18). Studies of ERα and ERβ knockout mice have revealed that ERα, but not ERβ, is indispensable for the negative-feedback effects of estradiol and thus maintenance of proper LH secretion from the pituitary. ERα−/− mice are characterized by hemorrhagic follicles and infertility (19). ERβ-mediated estradiol actions are vital to FSH-induced granulosa cell differentiation, and inactivation of ERβ leads to defects in follicular maturation at the antral stage (20, 21). Thus ERα and ERβ play different roles in modulation of HPG function.

There is growing evidence that ERα and ERβ also affect growth and differentiation: in cell lines ERβ negatively regulates ERα-dependent cell proliferation (22, 23). In many epithelial tissues studied, ERα mediates the proliferative response to estrogen, whereas ERβ represses proliferation and induces differentiation (24). We have shown that there is epithelial hyperproliferation and poor cellular differentiation in the prostate (25), colon (26), uterus (27), and mammary gland (28) of ERβ−/− mice. Furthermore, numerous clinical and in vitro studies suggest that imbalanced ERα and ERβ expression is a common feature and could be a critical step of estrogen-dependent tumor progression. These include the better prognosis of breast cancers, which express ERβ (29–31); the protective role of ERβ in development of colon cancer (32); the tumor suppressor role of ERβ in malignant mesothelioma (33); the proapoptotic role of the vitamin E metabolite tocotrienol, an ERβ ligand in breast cancer cells (34); and the effect of ERβ agonist on expression of TMPRSS2-ERG (a marker of very aggressive prostate cancer) (35). Introduction of ERβ into cancer cell lines reduces their proliferation in cell culture as well as in s.c. implants in immune compromised mice (36).

In the present study, we report that ERβ−/− female mice spontaneously develop pituitary and ovarian tumors. No tumors developed in ERβ−/− male mice and none were detected in ERα−/− or double knockout ERαβ−/− female mice. The ovarian tumors seem to have an overactivity of the TGFβ signaling pathway.

Results

Pituitary and Ovarian Tumors in 2-Year-Old ERβ−/− Female Mice.

In the present study, there were pituitary tumors in 23/23 of the female ERβ−/− mice 20 to 24 months of age. Spontaneous tumorigenesis was not observed in WT or ERα−/− age-matched male mice or in ERα−/− or ERαβ−/− female mice (Table 1). Four of the 23 WT female mice developed pituitary tumors. The absence of tumors in both ERα−/− and ERαβ−/− mice suggests that tumor development requires the presence of ERα. In most cases, visual examination of tumors revealed enlargement of the anterior lobe. In ERβ−/−female mice, the pituitary tumors were large (diameter > 3 mm), whereas four pituitary tumors formed in WT female mice were small-size tumors (diameter <3 mm) (Fig. 1 A and B).

Table 1.

Pituitary tumors in 2-year-old ERβ−/− mice

| Pituitary tumors/animals |

||

| Genotype | Female | Male |

| WT | 4/23 | 0/12 |

| ERβ−/− | 23/23 | 0/17 |

| ERα−/− | 0/6 | ND/ND |

| ERαβ−/− | 0/7 | ND/ND |

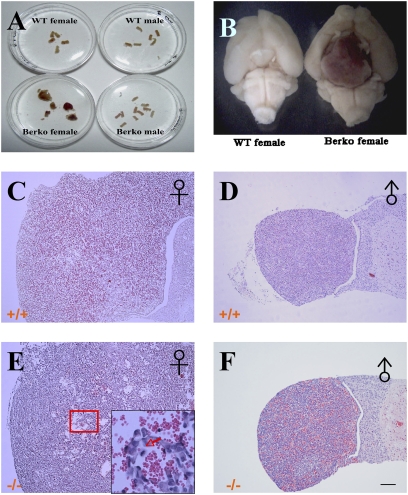

Fig. 1.

Gross morphology and histology of pituitaries of 2-year-old female WT mice and ERβ−/− mice. Large pituitary tumors were found in 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice, whereas there were none in 2-year-old WT or in male mice (A). (B) A ventral view of the brain of an ERβ−/− mouse with a macropituitary adenoma. Sections from WT male (D) and ERβ−/− male (F) were apparently normal, containing mostly acidophilic cells. (C) In WT female mice, the anterior lobe contained mostly acidophilic cells with few mitotic and apoptotic cells. (E) Anterior pituitaries of ERβ−/− female mice were markedly enlarged and contained mostly basophilic cells with clear mitotic figures. (Scale bars: 500 μm in C–F.)

Histological staining showed that pituitary sections from WT (Fig. 1D) and ERβ−/− (Fig. 1F) males were apparently normal, containing mostly acidophilic cells (including somatotropes and lactotropes), typical sinusoid vasculature features and the rare occurrence of either mitotic and apoptotic cells. Pituitary sections from aging WT female mice (Fig. 1C) showed enlarged anterior lobes containing mostly acidophilic cells with few mitotic and apoptotic cells. In pituitary sections from ERβ−/− female mice (Fig. 1E), the anterior pituitary was very enlarged with mostly basophilic cells. Both mitotic figures and apoptotic cells were abundant in pituitary tumors.

Ovarian tumors were found in ERβ−/− female mice with macropituitary tumors (Fig. 2B). No ovarian tumors and no hyperplasia were found in any of the WT female mice (Fig. 2A).

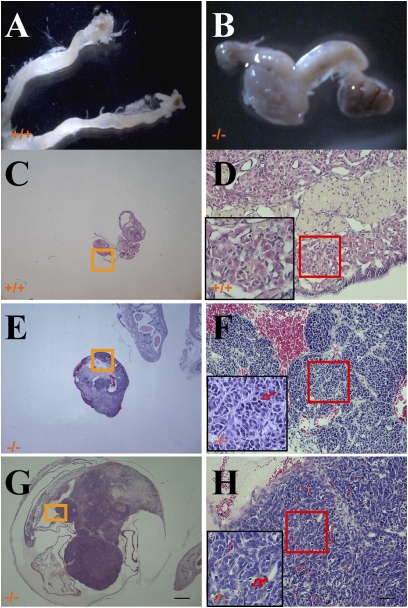

Fig. 2.

Ovarian tumors in 2-year-old ERβ−/− mice. Ovaries and uterine horns from WT mice appear to be of normal size and appearance (A). Bilateral ovarian tumors were present in ERβ−/− mice (B). Normal histological structure of the ovary of a 2-year-old WT female mouse (C). (D) A higher magnification showing absence of mitotic cells. Example of a granulosa cell tumor in ERβ−/− female mice (E). A higher magnification is shown (F), demonstrating evident mitotic cells (red arrow). (G) Example of an undifferentiated sex cord cell ovarian tumor in ERβ−/− female mice. (H) A higher magnification showing evident mitotic cells and apoptotic cells (red arrow). (Scale bars: 0.5 mm in C, E, and G; 50 μm in D, F, and H.)

The ovaries of WT female mice were of small size without detectable mitotic cells (Fig. 2 C and D). In 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice, the commonest ovarian tumors were of granulosa cell (Fig. 2 E and F) and undifferentiated sex cord cell types (Fig. 2 G and H) with abundant mitotic cells and apoptotic cells.

Immunohistological Analyses of Pituitary Tumors.

To characterize pituitary hormone expression in the tumors, histological analyses were performed on pituitary tumors. We analyzed the expression patterns of the markers of the mature pituitary gonadotropes (FSH/LH), corticotropes [adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)] and lactotropes (prolactin) (Fig. 3 A–F). Immunohistochemical analysis of pituitary sections with specific markers revealed that 21/23 of pituitary tumors of ERβ−/− female mice contained mostly FSH/LH-positive cells (Table 2). In the very large pituitary tumors, tissue structure was markedly disorganized and immunoreactivity for pituitary hormones diminished. Two macropituitary tumors were positive for gonadotropes, as well as for corticotropes and thyrotropes. Gonadotropes were observed only at the periphery of the tissue, with no staining detected in the core of the gland where the structure was completely destroyed. Two macropituitary tumors were negative for all three different markers. One small ERβ−/− pituitary tumor was positive for both FSH/LH and ACTH, whereas in the four pituitary tumors found in WT female mice, two tumors were positive for prolactin and two other tumors were positive for FSH/LH.

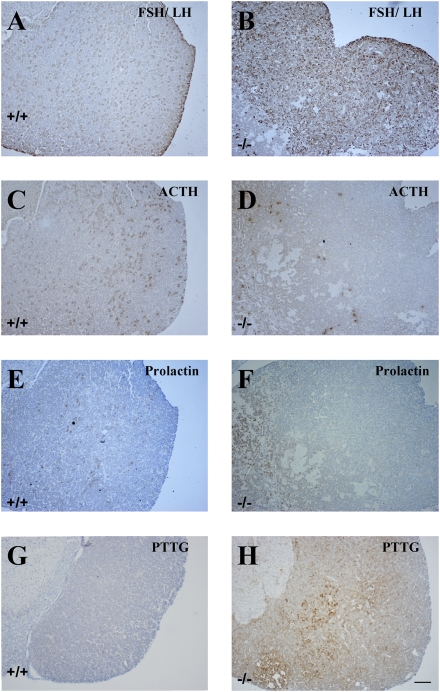

Fig. 3.

Immunohistological analysis of pituitary tumors. Serial sections of pituitary from WT (A, C, and E) and ERβ−/− (B, D, and F) female mice were stained using gonadotrope marker (FSH/LH), and nongonadotrope markers (ACTH and prolactin). In ERβ−/− female mice, specific staining shows that anterior pituitary tumor was of composed of gonadotropes, whereas the three markers were expressed equally in WT female mice. PTTG expression was high in ERβ−/− female mice (H); in contrast, few PTTG-positive cells were found in WT female mice (G). (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

Table 2.

Immunohistological analyses of pituitary tumors of 2-year old ERβ−/− female mice

| Pituitary tumor |

IHC analysis |

||

| Number | Diameter | Pituitary hormone | PTTC |

| ERβ−/− | |||

| 11 | >3 mm | FSH | +++ |

| 9 | <3 mm | FSH | ++ |

| 2 | >3 mm | − | − |

| 1 | <3 mm | FSH, ACTH | − |

| WT | |||

| 2 | <3 mm | Prolactin | − |

| 2 | <3 mm | FSH | − |

Pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) is known to induce angiogenesis during pituitary tumorigenesis. PTTG regulates βFGF secretion and is under the control of estrogen (37). It is expressed at low levels in normal human tissues but is abundant in cancer cell lines and in pituitary tumors. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that PTTG was localized in the cytoplasm of cells in the mouse pituitary tumors. In ERβ−/− female mice, the 11 macropituitary tumors were strongly stained for PTTG, whereas the nine micro pituitary tumors were less stained. No PTTG was detected in WT female mouse pituitaries (Fig. 3 G and H).

Overexpression of ERα and Ki67 in Pituitary, Uterus, and Ovary of 2-Year-Old ERβ−/− Female Mice.

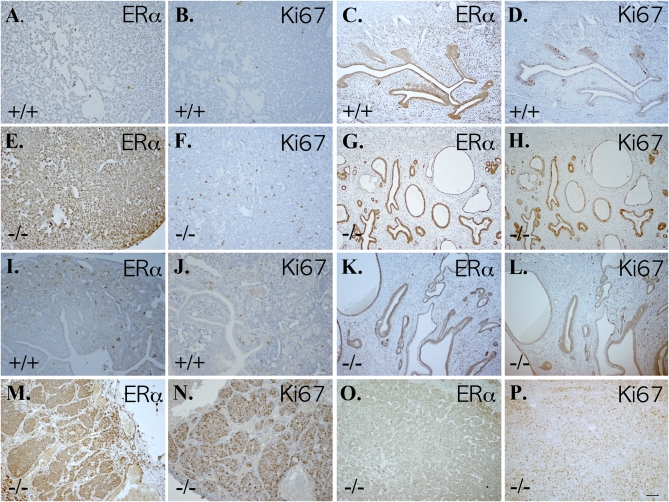

With the aim of evaluating the relationship between presence of ERα and cell proliferation, we checked ERα and Ki67 on sequential sections of pituitary tumors, uteri, and ovaries. In 2-year-old WT female mice, expression of both ERα and Ki67 was very low in pituitary glands (Fig. 4 A and B) and ovaries (Fig. 4 I and J). As expected, ERα expression was high in the uterus (Fig. 4C), but there were very few Ki67-positive cells (Fig. 4D). In ERβ−/− female mice, expression of ERα and Ki67 was high in the anterior pituitary lobe and most of Ki67-positive cells localized in the ERα-positive regions (Fig. 4 E and F). In the uterus (Fig. 4 G, H, K, and L) and ovary (Fig. 4 M–P), both ERα and Ki67 were highly expressed in ERβ−/− female mice with granulosa cell and undifferentiated sex cord cell ovarian tumors.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of ERα and Ki67 in pituitary, uterus, and ovary of 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice. Pituitary (A and B), uterus (C and D), and ovary (I and J) of WT female mice expressed very low levels of ERα (A, C, and I) and Ki67 (B, D, and J). In contrast, high expression levels of ERα (E) and Ki67 (F) were seen in pituitaries of ERβ−/− female mice. Granulosa cell ovarian tumors in ERβ−/− female mice expressed high levels of ERα (M) and Ki67 (N). The uteri of these mice also expressed high levels of ERα (G) and Ki67 (H). In mice with undifferentiated sex cord tumors there was low level of ERα (K) and Ki67 (L) in uterus, but high expression of ERα (O) and Ki67 (P) in the ovary. (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

TGFβ Signaling in ERβ−/− Mouse Ovaries.

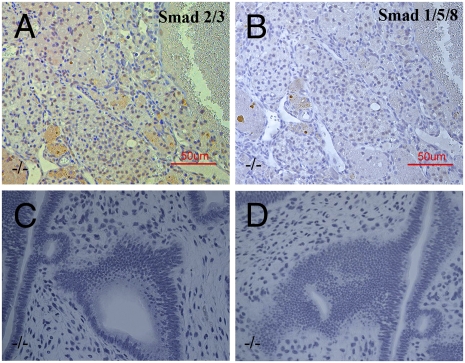

PhosphoSMAD2/3, a marker for the TGFβ pathway was highly expressed in the nuclei of ovarian tumor cells (Fig. 5A), although there was no positive staining for phosphoSMAD1/5/8, a marker for BMP activation (Fig.5B).

Fig. 5.

Ovarian tumors in ERβ−/− mouse and endometrial hyperplasia. PhosphoSMAD2/3 was highly expressed in the granulosa cell tumors from 2-year-old ERβ−/− mice (A). There was no positive staining for PhosphoSMAD1/5/8 in the granulosa cell tumors in ERβ−/− mouse ovary (B). There was extreme endometrial hyperplasia with epithelial invasion of the stroma in ERβ−/− mice at 18 months of age (C and D). (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

Age at Which Ovarian Tumors Develop.

Because of the high mitotic indices in the ovarian tumors in 2-year-old mice, we anticipated that these were very rapidly growing tumors and were initiated after the mice were one-year-old. We therefore examined female ERβ−/− mice at 15, 17, and 18 months of age to determine when the ovarian and pituitary tumors became evident. There were four mice in each age group, and all of these mice had ovarian and pituitary tumors but they were much smaller than those found in 2-year-old mice. Ovarian hyperplasia was observed in ERβ−/− female mice with micropituitary tumors. All of the ovarian tumors were granulosa cell tumors, and they appeared to be secreting estrogen because there was hyperplasia and a high proliferation index in the endometrium of these mice. In some mice, there was extreme endometrial hyperplasia with epithelial invasion of the stroma (Fig. 5 C and D). This observation is compatible with our previous finding that in ERβ−/− mice the proliferative response of the uterus to estrogen is exaggerated (27).

Overexpression of GnRH (LHRH-Positive) and NPY in the Hypothalamus of ERβ−/− Female Mice.

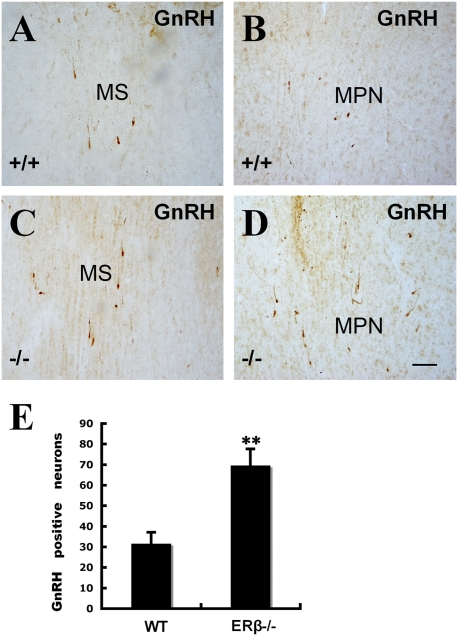

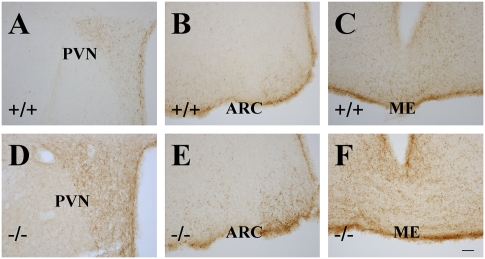

Recent identification of ERβ within GnRH neurons of the rodent and human brain suggests that estrogens may exert direct actions upon GnRH neurons through ERβ. Using immunohistochemistry to identify GnRH-positive cells, we found that the expression pattern of GnRH in the hypothalamus was similar in ERβ−/− and WT female mouse brains. There was a twofold increase (Fig.6E) in the number of GnRH-positive cells in medial septal nucleus and medial preoptic nucleus of ERβ−/− female mouse hypothalami (Fig. 6 C and D) compared to WT (Fig. 6 A and B) female mouse hypothalami. There is evidence that estrogens can affect NPY synthesis in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and increase release of NPY in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) through receptors localized in NPY neurons (38). NPY colocalized with GnRH in neurons in the median eminence (ME), PVN, and ARC of the hypothalamus. NPY expression was higher in ERβ−/− (Fig. 7 D–F) female mice than in WT (Fig. 7 A–C) female mice. These data suggest that NPY overexpression contributes to a high level of GnRH in the hypothalamus of 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice.

Fig. 6.

GnRH (LHRH)-expressing neurons in the hypothalami of 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice. The number of cells expressing GnRH (LHRH) in the medial septal nucleus (C) and medial preoptic nucleus (D) of ERβ−/− female mice was higher than that seen in WT controls (A and B). The total number of GnRH (LHRH)-positive neurons in the medial septal nucleus and medial preoptic nucleus was counted in 10 sections from each mouse (E). There was a more than twofold increase in the number of GnRH (LHRH)-positive neurons in the hypothalami of ERβ−/− female mice. (MS: medial septal; MPN: medial preoptic nucleus) (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

Fig. 7.

NPY expression in the hypothalami of ERβ−/− mice. NPY expression in paraventricular nucleus (D), arcuate nucleus (E), and medial eminence (F) was higher in 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice than in WT female mice (A–C). (PVN, paraventricular nucleus; ARC, arcuate nucleus; ME, medial eminence) (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

Discussion

ERα and ERβ are differently regulated in estrogen-sensitive tissues. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the ERα/ERβ ratio can affect cell proliferation (39). In agreement with this, loss of ERβ has been found to increase susceptibility of tissues to estrogen-induced carcinogenesis in several animal models: ERβ deficiency enhances small intestinal tumorigenesis (40) and down-regulation of ERβ and the coregulator SNURF/RNF4 genes contributes to testicular tumorigenesis (41). The question still remains as to whether loss of ERβ alone can lead to spontaneous tumorigenesis. In the present study, we report that loss of ERβ leads to spontaneous tumorigenesis in both the pituitary and ovary in female mice 15 to 24 months of age. Because there is no spontaneous tumorigenesis in ERα−/− or ERαβ−/− female mice, it appears that tumor development requires the presence of ERα. Our study showed that levels of ERα in the pituitary, ovary, and uterus were significantly higher in ERβ−/− mice than in WT mice. Staining of sequential sections showed that high expression of ERα was accompanied by a high level of proliferation measured with Ki67-specific antibodies. We conclude that a change in ERα/ERβ ratio in favor of ERα can lead to spontaneous tumorigenesis in both the pituitary and ovary.

Histological staining showed a markedly enlarged anterior pituitary containing mostly basophilic cells in ERβ−/− female mice. Immunohistochemical analysis with specific markers revealed that most of pituitary tumors in ERβ−/− female mice were FSH/LH positive. Little is known about the molecular pathogenesis of gonadotrope-specific pituitary tumors. Development of pituitary adenoma is considered to be a multistep process including genetic alterations and hormone-induced proliferation (42). The effect of hormone stimulation on the formation of pituitary adenoma is supported by evidence that pregnancy and hypothyroidism lead to pituitary hyperplasia. Moreover, a recent study reported one case of gonadotrope macroadenoma and two cases of gonadotrope cell hyperplasia in patients with Klinefelter syndrome probably due to continuous stimulation of gonadotropes because of lack of androgen feedback (43). In the hypothalamus, there were more GnRH-positive neurons in 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice than in age-matched WT mice suggesting that increased GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus may contribute to gonadotrope macroadenoma.

Neuropeptide Y has been reported to be involved in the regulation of GnRH neuronal function (44). In the rat, NPY stimulates GnRH release from the hypothalamus in the presence of estrogen, whereas it inhibits GnRH during estrogen deprivation (45). In the present study, NPY expression in the PVN, ARC, and ME of hypothalamus was increased significantly compared to WT female mice. This indicates that NPY overexpression in the hypothalamus of 2-year-old ERβ−/− female mice mediates GnRH release, leading to pituitary hyperplasia.

Recent identification of ERβ within GnRH neurons of the rodent and human brains indicates that estrogens may exert direct actions upon GnRH neurons exclusively through ERβ. Loss of ERβ may also directly affect GnRH neurons, but further studies are needed to explore the biological significance of this pathway.

In ERβ−/− mice gonadotropin-positive pituitary tumors were accompanied by ovarian sex cord tumors. They are characterized by high levels of proliferation and apoptosis. In the present study, we found that in the sex cord ovarian tumors there is increased LH receptor and SMAD3 expression. This is similar to mice in which inhibin has been inactivated (46). We conclude that in the absence of ERβ, there is a defect in the inhibitory wing of the TGFβ signaling pathway and the proliferative actions of FSH/SMAD3 continue unopposed. In addition, high expression of ERα contributes to the malignancy of the tumors by increasing estrogen-stimulated proliferation.

The marked hyperplasia seen in the endometrium of the mice bearing granulosa cell tumors is supportive evidence for a role of ERβ in the uterus. The uterus is thought of as an ERα-regulated tissue. We have shown an exaggerated proliferative response of the uterus to estrogen in our ERβ−/− mice (27).

There is some argument as to why the phenotype of the ERβ−/− mice produced in the laboratory of Oliver Smithies (47) is different from the phenotype of those produced by the Chambon Lab in Strasbourg (48). The Strasbourg mice are reported to be completely normal except for infertility in the female mice. The Smithies female mice are also infertile and, as reported in the present study, have abnormalities in GnRH secretion. The big difference between the two knockout strains is that in the Smithies mouse, the neo cassette remains in the ERβ gene but has been removed in the Strasbourg mouse. So unless the Strasbourg mice are infertile for a completely different reason than are the Smithies mice, it is difficult to understand why they do not develop the abnormalities, which we have described in the present study.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a role for ERβ in pituitary and ovarian tumorigenesis in aging mice and indicates that ERβ directly modulates proliferation in estrogen sensitive tissues. The data are supportive evidence for other studies, which show that the ERα/ERβ ratio is important for controlling cellular proliferation. Further studies are needed to explore the mechanism behind the increase in ERα expression when ERβ is inactivated because this is a pattern seen in most cancers.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue Preparation.

ERβ−/− mice were generated as described (47). Heterozygous mice were used for breeding. All animals were housed in the Karolinska University Hospital animal facility (Huddinge, Sweden) in a controlled environment on a 12-h light/12-h dark illumination schedule and fed a standard pellet diet with water provided ad libitum. To obtain tissues, mice were anesthetized deeply with CO2 and perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4). Tissues were collected and postfixed in the same fixative overnight at 4 °C. After fixation, tissues were processed into either paraffin (6 μm) or frozen (30 μm) sections. All animal experiments were approved by Stockholm's Södra Försöksdjursetiska Nämnd.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded alcohol, and processed for antigen retrieval by boiling in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 5 min. The sections were incubated in 0.5% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase and then were incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. To block nonspecific binding, sections were incubated in 3% BSA for 1 h at 4 °C. Sections were then incubated with anti-phosphoSMAD 2/3 (Chemicon), anti-phosphoSMAD 1/5/8 (Chemicon), anti-LHRH (GnRH) (Chemicon), anti-FSH/LH (Chemicon), anti-ACTH (Chemicon), anti-PTTG (Zymed Lab), anti-prolactin (DAKO), anti-ERα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Ki67 (Novocastra), and anti-NPY (Peninsular Laboratories) in 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 overnight at room temperature. BSA replaced primary antibodies in negative controls. After washing, sections were incubated with the corresponding secondary biotinylated antibodies in 1:200 dilutions for 2 h at room temperature. The Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) was used for the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method according to the manufacturer's instructions. Peroxidase activity was visualized with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAKO). The sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through an ethanol series to xylene, and mounted.

Data Analysis.

Stained brain sections (10–12 sections per area for each mouse) were examined under a light microscope, and images were captured under 20× magnification. GnRH-positive neurons were visualized with GnRH antibody and counted manually on the captured images. Estimates of the number of GnRH-positive neurons were made based on the counts of the 10 images showing the highest number of GnRH-labeled neurons. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Shupnik MA, Chin WW. Molecular biology of the pituitary gonadotropins. Endocr Rev. 1990;11:177–199. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-1-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen SL, Ottem EN, Carpenter CD. Direct and indirect regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by estradiol. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1771–1778. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.019745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shupnik MA, Gharib SD, Chin WW. Estrogen suppresses rat gonadotropin gene transcription in vivo. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1842–1846. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-5-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. Regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:559–584. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Badger TM, Chin WW. Sex steroid hormone regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone subunit messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:294–299. doi: 10.1172/JCI113072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shupnik MA, Gharib SD, Chin WW. Divergent effects of estradiol on gonadotropin gene transcription in pituitary fragments. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:474–480. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-3-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter P, et al. Cloning of the human estrogen receptor cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7889–7893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatoya S, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta genes in the mediobasal hypothalamus, pituitary and ovary during the canine estrous cycle. Neurosci Lett. 2003;347:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hrabovszky E, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons express estrogen receptor-beta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2827–2830. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner DCDL, Dufourny L. Oestrogen receptor beta-immunoreactive neurones in the ovine hypothalamus: Distribution and colocalisation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchenthaler I. Estrogen stimulates galanin expression within luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-immunoreactive (LHRH-i) neurons via estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) in the female rat brain. Neuropeptides. 2005;39:341–343. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchenthaler I, Hoffman GE, Lane MV. Estrogen and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta)-selective ligands induce galanin expression within gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone-immunoreactive neurons in the female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2760–2765. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuiper GG, et al. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–870. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchner NA, Garlick C, Ben-Jonathan N. Cellular distribution and gene regulation of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the rat pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3976–3983. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scully KM, et al. Role of estrogen receptor-alpha in the anterior pituitary gland. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:674–681. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sar M, Welsch F. Differential expression of estrogen receptor-beta and estrogen receptor-alpha in the rat ovary. Endocrinology. 1999;140:963–971. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelletier G, Labrie C, Labrie F. Localization of oestrogen receptor alpha, oestrogen receptor beta and androgen receptors in the rat reproductive organs. J Endocrinol. 2000;165:359–370. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmen JM, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor knockout mice: Phenotypes in the female reproductive tract. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2003;17:169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glidewell-Kenney C, et al. Nonclassical estrogen receptor alpha signaling mediates negative feedback in the female mouse reproductive axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8173–8177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drummond AE, Baillie AJ, Findlay JK. Ovarian estrogen receptor alpha and beta mRNA expression: Impact of development and estrogen. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;149:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu MM, et al. Opposing action of estrogen receptors alpha and beta on cyclin D1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24353–24360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews J, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen signaling: A subtle balance between ER alpha and ER beta. Mol Interv. 2003;3:281–292. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.5.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heldring N, et al. Estrogen receptors: How do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imamov O, et al. Estrogen receptor beta regulates epithelial cellular differentiation in the mouse ventral prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9375–9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wada-Hiraike O, et al. Role of estrogen receptor beta in colonic epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2959–2964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511271103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada-Hiraike O, et al. Role of estrogen receptor beta in uterine stroma and epithelium: Insights from estrogen receptor beta-/- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18350–18355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608861103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng G, Weihua Z, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors ER alpha and ER beta in proliferation in the rodent mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3739–3746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwao K, Miyoshi Y, Egawa C, Ikeda N, Noguchi S. Quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-beta mRNA and its variants in human breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:733–736. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001201)88:5<733::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaaban AM, et al. Declining estrogen receptor-beta expression defines malignant progression of human breast neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1502–1512. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roger P, et al. Decreased expression of estrogen receptor beta protein in proliferative preinvasive mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2537–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostafaie N, et al. Correlated downregulation of estrogen receptor beta and the circadian clock gene Per1 in human colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:642–647. doi: 10.1002/mc.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinton G, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta affects the prognosis of human malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4598–4604. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Comitato R, et al. A novel mechanism of natural vitamin E tocotrienol activity: Involvement of ERbeta signal transduction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E427–E437. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00187.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonkhoff H, Berges R. The evolving role of oestrogens and their receptors in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartman J, et al. Tumor repressive functions of estrogen receptor beta in SW480 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6100–6106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chesnokova V, Melmed S. Pituitary tumour-transforming gene (PTTG) and pituitary senescence. Horm Res. 2009;71(Suppl 2):82–87. doi: 10.1159/000192443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hilke S, Holm L, Man K, Hökfelt T, Theodorsson E. Rapid change of neuropeptide Y levels and gene-expression in the brain of ovariectomized mice after administration of 17beta-estradiol. Neuropeptides. 2009;43:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews J, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER) beta modulates ERalpha-mediated transcriptional activation by altering the recruitment of c-Fos and c-Jun to estrogen-responsive promoters. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:534–543. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weyant MJ, et al. Reciprocal expression of ERalpha and ERbeta is associated with estrogen-mediated modulation of intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2547–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirvonen-Santti SJ, et al. Down-regulation of estrogen receptor beta and transcriptional coregulator SNURF/RNF4 in testicular germ cell cancer. Eur Urol. 2003;44:742–747, discussion 747. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kastelan D, Korsic M. High prevalence rate of pituitary incidentaloma: Is it associated with the age-related decline of the sex hormones levels? Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:307–309. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheithauer BW, et al. The pituitary in klinefelter syndrome. Endocr Pathol. 2005;16:133–138. doi: 10.1385/ep:16:2:133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaikwad A, Biju KC, Muthal PL, Saha S, Subhedar N. Role of neuropeptide Y in the regulation of gonadotropin releasing hormone system in the forebrain of Clarias batrachus (Linn.): Immunocytochemistry and high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometric analysis. Neuroscience. 2005;133:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woller MJ, Campbell GT, Liu L, Steigerwalt RW, Blake CA. Estrogen alters the effects of neuropeptide-Y on luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone release in female rats at the level of the anterior pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2675–2681. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q, Graff JM, O'Connor AE, Loveland KL, Matzuk MM. SMAD3 regulates gonadal tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2472–2486. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krege JH, et al. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antal MC, Krust A, Chambon P, Mark M. Sterility and absence of histopathological defects in nonreproductive organs of a mouse ERbeta-null mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2433–2438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712029105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]