Abstract

The primordium that generates the embryonic posterior lateral line of zebrafish migrates from the head to the tip of the tail along a trail of SDF1-producing cells. This migration critically depends on the presence of the SDF1 receptor CXCR4 in the leading region of the primordium and on the presence of a second SDF1 receptor, CXCR7, in the trailing region of the primordium. Here we show that inactivation of the estrogen receptor ESR1 results in ectopic expression of cxcr4b throughout the primordium, whereas ESR1 overexpression results in a reciprocal reduction in the domain of cxcr4b expression, suggesting that ESR1 acts as a repressor of cxcr4b. This finding could explain why estrogens significantly decrease the metastatic ability of ESR-positive breast cancer cells. ESR1 inactivation also leads to extinction of cxcr7b expression in the trailing cells of the migrating primordium; this effect is indirect, however, and due to the down-regulation of cxcr7b by ectopic SDF1/CXCR4 signaling in the trailing region. Both ESR1 inactivation and overexpression result in aborted migration, confirming the importance of this receptor in the control of SDF1-dependent migration.

Keywords: collective cell migration, CXCR7, FGF, SDF1, Wnt

Programmed cell migration plays a major role in normal development, as well as in various pathological conditions. The development of the posterior lateral line system (PLL) has recently emerged as a useful in vivo system to study collective cell migration and to elucidate the genetic network that underlies it (1). The embryonic PLL of the zebrafish comprises seven to eight sensory organs, the neuromasts, which are sequentially deposited between head and tail tip by a migrating primordium (2, 3). Primordium migration depends on interactions between the chemokine SDF1 (CXCL12), which is expressed along the pathway of migration, and its two receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7, which are expressed in the primordium (4 –8). The same three molecules have also been implicated in the migration of zebrafish germ cells (9) and facial motoneurons (10). In mammals, SDF1/CXCR4 signaling plays a major role in the migration of several types of cancer cells, notably breast and ovary cancers.

The domains of expression of cxcr7b and of cxcr4b in the migrating PLL primordium are largely complementary, cxcr4b being expressed most intensely in the leading region, whereas cxcr7b is expressed exclusively in the trailing region (7, 8). We have proposed that this asymmetry depends on an antagonistic interaction between the two receptors, whereby CXCR4 signaling leads to repression of cxcr7b in the leading cells, whereas CXCR7 sequestering of their common ligand, SDF1, prevents CXCR4 activation in the trailing region. This interaction would result in a gradient of CXCR4 signaling across the primordium and confer directionality to the migration (7).

Recent studies have revealed another asymmetry in the migrating primordium. Wnt signaling takes place in the leading region and activates FGF signaling in the medial and trailing regions (11). FGF signaling, in turn, organizes the primordium cells in rosettes that prefigure future neuromasts (12, 13) and restricts Wnt signaling to the leading cells (11). Wnt signaling in the leading cells represses cxcr7b and has been hypothesized to activate indirectly cxcr4b in the leading region by antagonizing a putative repressor of cxcr4b (11). Here we show that the estrogen receptor ESR1 is a repressor of cxcr4b, we confirm our previous proposal that SDF1/CXCR4 signaling represses cxcr7b, and we reexamine the relation between the CXCR4/CXCR7 and the Wnt/FGF systems.

Results

To identify elements that may contribute to the control of cxcr4b expression, we studied the cxcr4b promoter region. Starting with a 6.6-kb promoter region, including the first exon and intron, that drives expression in the PLL primordium, we have been able to trim it down to a 139-bp domain, including the initiation ATG, that still allows expression in the primordium or in neuromasts in transient assays (Fig. 1 A and B), albeit at a relatively low level compared to the 6.6-kb promoter. A stable transgenic line expressing a membrane-bound RFP under the control of this 139-bp minimal promoter shows strong red fluorescence (Fig. 1C) nearly superimposed on the green fluorescence of the reporter line cldnb:gfp (Fig. 1D), where all cells of the lateral line and otic systems express a membrane-bound GFP (6). Expression of RFP is confined to the PLL, however (Fig. 1E), showing that PLL specificity of cxcr4b expression is maintained in the 139-bp promoter. Bioinformatic analysis revealed a number of presumptive binding sites in this minimal promoter, including a putative binding site for ESR1 coupled to a Specificity Protein 1 (SP1) binding site (Fig. 1F), a frequently found combination (14). Comparison with the human cxcr4 promoter revealed a similar arrangement within a sequence of 157 bp just upstream of the initiation ATG (Fig. 1F), a sequence that has been shown to allow the expression of a reporter gene in cxcr4-expressing cells (15). Interestingly, no ESR1 binding site is present in the corresponding region of the other zebrafish CXCR4 gene, cxcr4a (Fig. 1F), which is not expressed in the PLL primordium (16). These data prompted us to examine whether ESR1 plays any role in controlling the migration of the primordium.

Fig. 1.

The minimal promoter of cxcr4b. (A and B) transient expression of RFP under the control of the 139-bp cxcr4b promoter fragment in a migrating primordium (A) and in a deposited neuromast (B) in cldnb:gfp embryos. (Left) RFP fluorescence, (Right) RFP in red, merged with GFP in green. (C) Stable expression of RFP driven by the 139-bp promoter in a line doubly transgenic for cxcr4b:rfp and cldnb:gfp. (D) Coexpression of RFP (red) and GFP (green) in the same embryo. (C and D) Assembled from four consecutive frames of a Z-stack; the slight mismatch between green and red, in some cells, is due to migration during the imaging process. In this and all other figures anterior is to the left, and the primordium is migrating to the right. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) (E) Low-scale view of an embryo doubly transgenic for cxcr4b:rfp and cldnb:gfp, illustrating the complete absence of RFP expression in anterior lateral line neuromasts (ALL) and in the infraorbital anterior lateral line primordium (ALL io) as well as in the otic system (arrowheads). Faint RFP fluorescence can be detected in the PLL ganglion (PLLg). (F) Comparison of the sequences upstream of the TATA box in Danio cxcr4b, Homo cxcr4, and Danio cxcr4a promoters. The 139-bp cxcr4b minimal promoter defined by us begins one base upstream of the ESR1 putative binding site and includes the initiation ATG; the 157-bp minimal promoter defined in Homo (15) begins 10 bases upstream of the ESR1 binding site and does not include the initiation ATG. The corresponding sequence in the promoter of cxcr4a is also shown. Putative binding sites according the TESS software are colored. The ESR1 binding sites in cxcr4b and human cxcr4 (red) are both followed by a C, consistent with the presence of a pyrimidine at this position in the consensus binding site. The binding sites for SP1 and TATA Binding Protein have been shown to be instrumental for cxcr4 expression in the minimal human promoter (26).

We first assessed the functional importance of ESR1 activity in PLL development by morpholino oligonucleotide inactivation of the esr1 gene. In untreated cldnb:gfp embryos, the primordium is reaching the tip of the body (somite 29/30, n = 25) at 48-hours postfertilization (hpf). In 70% of the esr1-morpholino oligonucleotides (MO) injected embryos, the primordium is much delayed and has only reached somite 17 ± 4 at the same age (n = 54); 48 hpf, embryos injected with a control, mismatched morpholino are negligibly different from untreated embryos (somite 29 ± 2, n = 106). To better characterize the migration defect, we followed the primordium by time lapse imaging in esr1-MO embryos. In 20 out of 28 morphant embryos, the primordium migrated at a reduced speed (1.1 somite/h in untreated cldnb:gfp embryos; Fig. 2A and Movie S1, vs 0.6 somite/h on average in morpholino-injected embryos; Fig. 2B and Movie S2). At about 40 hpf, the morphant primordium further slowed down, and eventually formed two neuromasts (Fig. 2C and Movie S2). We conclude that esr1 is required for normal migration of the primordium.

Fig. 2.

Migration of the PLL primordium is altered in esr1-MO embryos. (A) Three frames of a time-lapse movie of primordium migration in a cldnb:gfp embryo at 35 (t = 0), 38, and 41 hpf, respectively. At 41 hpf, the primordium has just migrated out of the field. (B) Five frames of a time-lapse movie of the primordium in an esr1-MO1 injected embryo at 35 (t = 0), 38, 41, 44, and 48 hpf, respectively. Migration is two to three times slower than in untreated cldnb:gfp embryos and eventually comes to a halt around 45 hpf. (C) In the same embryo, the immobile primordium has fragmented into two neuromasts at 51 hpf. (Scale bar in A: 50 μm.)

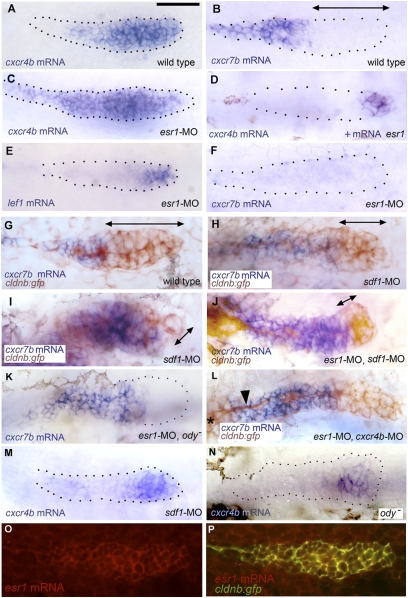

Given the presence of a putative ESR1-binding site in the promoter region of cxcr4b, we asked whether the defective migration in esr1-MO embryos might be due to a change in the expression of cxcr4b. In control embryos, cxcr4b is expressed at a high level in the leading two-thirds of the primordium and at a much lower level in the trailing region (3) (Fig. 3A). In 56% of esr1-MO injected embryos (n = 43), cxcr4b is clearly expressed throughout the primordium, as well as in the deposited cells (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the expression of cxcr4b is derepressed in the trailing region.

Fig. 3.

Patterns of gene expression in the PLL primordium. (A and B) Expression of cxcr4b and cxcr7b in 32-hpf control embryos. (C and D) Expression of cxcr4b in conditions of esr1 loss-of-function (C) and gain-of-function (D). The change in expression between A and C was observed in 75% of the injected embryos, respectively, the change between A and D in 30% of the injected embryos. (E and F) Expression of lef1 and cxcr7b in esr1 loss-of-function conditions. (G and H) Expression of cxcr7b (blue) and of gfp (brown) in a 32-hpf control cldnb:gfp embryo (G), in an sdf1-MO embryo (H; an extreme case of cxcr7b domain expansion is shown in I). (J–L) Rescue of cxcr7b expression in esr1-MO embryos that are also sdf1-MO (J), mutant for ody (K), or morphant for cxcr4b (L; note the nerve, arrowhead, extending from the ganglion, asterisk at the left of the figure, under the stalled primordium). (M and N) Expression of cxcr4b in 32-hpf sdf1-MO injected (M) or ody − (N) homozygous embryos; the photograph in N was taken under Nomarski optics to illustrate the extent of the primordium. (O and P) Expression of esr1 in a 32-hpf migrating primordium as revealed by fluorescent in situ hybridization using a rhodamine-coupled antidioxygenin antibody (O) and coexpression of esr1 and cldnb:gfp in the same embryo (P; confocal imaging). (A–F, K, and M) are bright-field pictures without Nomarski optics, to facilitate the detection of expression patterns. The primordia are outlined by dotted lines, based on images taken under Nomarski optics as illustrated in N. Double-headed arrows indicate the extent of the region where cxcr7b expression is not detectable.

It has been shown that constitutive activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway results in an extended expression of cxcr4b (11). It could be, therefore, that the derepression of cxcr4b in esr1-MO embryos (Fig. 3C) is indirect and results from an ectopic activation of the Wnt/β-catenin in the trailing region of the primordium. We observed, however, that the expression of lef1 (a target of Wnt signaling) (11) remains restricted to the leading third of the primordium in esr1 morphant embryos, much as in untreated embryos (Fig. 3E). We conclude that ESR1 controls cxcr4b expression independently of Wnt activity.

We confirmed that ESR1 acts as a repressor of cxcr4b expression by a gain-of-function approach. We injected mRNA coding for ESR1 in one-cell stage cldnb:gfp embryos zygotes and looked for abnormalities of primordium migration. Out of 27 injected embryos, migration was reduced by more than 50% in 23/54 sides (43%). Among the defective primordia, 16 (69%) showed severely reduced (Fig. 3D and Fig. S1A) or absent (Fig S1B) cxcr4b expression. Fifteen of the 16 primordia with markedly reduced cxcr4b expression had reached somite 2.1 ± 2, whereas the 31 primordia with mildly reduced or unimpaired migration had reached somite 10.0 ± 2.3 on average.

We wondered whether ESR1 is also involved in the control of cxcr7b. The expression of cxcr7b in control embryos is dynamic and may extend over the trailing one fifth of the primordium, just after neuromast deposition, to its trailing two fifths, just before deposition (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, cxcr7b expression is not detectable in the primordium, nor in the deposited cells, in a vast majority of 30-hpf esr1-MO embryos (73%, n = 44; Fig. 3F), showing that ESR1 is required for the proper expression of cxcr7b in the trailing cells. The absence of cxcr7b expression in esr1-MO embryos may reflect a direct requirement for ESR1, or may be a consequence of cxcr4b ectopic expression in the trailing cells. We proposed previously that SDF1/CXCR4 signaling represses cxcr7b, thereby confining the presence of CXCR7 to the trailing region of the primordium (7). As this result has been questioned (8), we reexamined this question in cldnb:gfp embryos where the primordium can be unequivocally delimited by anti-GFP immunolabeling.

We observed that inactivation of SDF1 signaling by sdf1-MO injection results in a marked expansion of the domain of cxcr7b expression in 84% (n = 45) of the injected embryos, consistent with our previous observations (compare Fig. 3 G and H; an extreme case is shown in Fig. 3I and the case of a primordium migrating along an ectopic path, and therefore in complete absence of SDF1, is shown Fig. S2B). In all cases, the change in cxcr7b expression was accompanied by severe impairment of migration. The expanded domain of cxcr7b expression never included the anteriormost cells of the primordium, however, suggesting that some other factor, possibly Wnt signaling, can repress cxcr7b independently of SDF1/CXCR4 signaling.

We then examined whether the effect of esr1 inactivation on cxcr7b expression is due to cxcr4b ectopic expression. If the down-regulation of cxcr7b in the trailing region of esr1-MO embryos results from ectopic SDF1/CXCR4 signaling, inactivation of sdf1 or cxcr4b should reverse the effect of esr1 inactivation. One would therefore expect to see a rescue of cxcr7b expression in esr1-MO, sdf1-MO and in esr1-MO, cxcr4b-MO3 double morphant embryos, or in esr1-MO, ody – embryos, where cxcr4b is mutated (17). If, on the other hand, ESR1 were directly required for cxcr7b expression, then embryos that lack both ESR1 and SDF1, or ESR1 and CXCR4 activity should lack cxcr7b expression, much like in the single esr1-MO condition. To ensure that the results were not biased by the presence of nonmorphant embryos, we assessed the expression domain of cxcr7b only in embryos that showed an altered migration.

We observed a rescue of cxcr7b expression in 81% of esr1-MO, sdf1-MO embryos (n = 42) that showed altered migration of the primordium (compare Fig. 3 J to F). This rescue demonstrates that the absence of ESR1 indirectly represses cxcr7b. The expression of cxcr7b reached the anterior half of the primordium in 38% of the embryos (Fig. 3J). A similar rescue was obtained in 87% of esr1-MO, ody− embryos (n = 28; Fig. 3K), with an expanded domain of cxcr7b expression in 14% of the embryos. Rescue of cxcr7b expression was also observed in 36% of esr1-MO, cxcr4b-MO3 embryos (n = 32; Fig. 3L), with an expanded cxcr7b domain in 16% of the embryos. Altogether, the results clearly show that ectopic SDF1/CXCR4 signaling is responsible for the extinction of cxcr7b expression in the trailing region of esr1-MO primordia.

We examined whether the asymmetry in the expression of cxcr4b and cxcr7b may be further enhanced by positive feedback of SDF1/CXCR4 signaling on cxcr4b expression. We observed in 69% of the cases (n = 45) a marked reduction of the domain of cxcr4b expression in sdf1-MO embryos (compare Fig. 3 M to A). A decrease in the expression of cxcr4b was also observed in ody− mutant embryos, where cxcr4b is mutationally inactivated (Fig. 3N). Interestingly, even when the primordium migrates away from its normal path in sdf1-MO embryos, ensuring that no residual SDF1 activity can be invoked, cxcr4b is still expressed in a leading domain where cxcr7b expression is prevented (Fig. S2A). The leading domain, where the expression of cxcr4b is maintained in the absence of SDF1/CXCR4 signaling (Fig. 3 M and N), and where cxcr7b expression is prevented even in the absence of SDF1/CXCR4 (Fig. 3 H–J), appears similar to the domain of lef1 expression (Fig. 3E), suggesting that expression of cxcr4b in the leading cells (and repression of cxcr7b in the same cells) may be under direct control of Wnt signaling.

The down-regulation of cxcr4b in the trailing region, but not in the leading two-thirds of the primordium, could reflect a localized expression of esr1 in the trailing cells. This is not the case: in situ hybridization reveals that esr1 is weakly but homogeneously expressed throughout the primordium (Fig. 3 O and P). Two alternative mechanisms can account for the coexpression of the repressor gene esr1 and of its target cxcr4b in the leading cells: either ESR1 needs a corepressor, which itself is only present, or active, in the trailing region, or else the repression by ESR1 is counteracted by an activating mechanism in the leading region.

Finally, we examined whether the effect of ESR1 on cxcr4b expression is direct or indirect, by examining the expression of rfp driven by the cxcr4b promoter in the presence of an excess of ESR1. One of three stable transgenic lines for the 139-bp-rfp construct shows fluorescence in the entire primordium and in deposited cells (Fig. 1C), and we verified by in situ hybridization that rfp is also expressed throughout the primordium in this line. Another two stable transgenic lines only produced weak fluorescence and no mRNA detectable by in situ hybridization, making it impossible to decide whether the ubiquitous expression shown Fig. 1C is due to an inefficient ESR1 binding site (presumably due to the lack of all 5′ flanking sequences) (Fig. 1F) or to overexpression induced by surrounding sequences. Because the putative ESR1 binding site of the 139-bp promoter may not be fully functional, we decided to use the 250-bp promoter (same 3′ end as the 139-bp minimal promoter) to drive rfp expression in transient assays.

We first determined whether the coinjection of esr1 mRNA with the 250-bp-rfp construct would affect rfp expression. We found that, whereas 50% (n = 140) of the embryos injected with the construct alone express rfp in the migrating primordium (Fig. S3A), the proportion of cases where rfp is not expressed increases from 50 to 84% (n = 70) in embryos coinjected with the construct and with esr1 mRNA (Fig. S3B). This difference is highly significant (P = 0.003, X2 test) and indicates that ESR1 does repress transcription controlled by the 250-bp cxcr4b promoter. We then repeated the experiment using a 250-bp promoter that had been mutated for the putative recognition site of ESR1. In this case, the proportion of positive primordia was 46% (n = 128) in embryos injected with the plasmid alone and 34% (n = 80) when the construct was coinjected with esr1 mRNA, a marginal difference (P = 0.52, X2 test). Because the marked repression of the 250-bp promoter by ubiquitous ESR1 activity is largely if not fully reversed when the putative ESR1 binding site within the 250-bp promoter is mutated, we conclude that ESR1 acts directly on this promoter.

Discussion

We showed that a fragment of 139 bp upstream of and including the cxcr4b initiation ATG specifically directs the expression of a reporter gene in the migrating PLL primordium but not in anterior lateral line components. This sequence comprises at its 3′ end a binding site for the estrogen receptor ESR1. This binding site may not be sufficient for full repression of cxcr4b because we observed in a stable transgenic line, that the reporter gene keeps being expressed in the trailing cells where endogenous cxcr4b is turned off. Nevertheless we showed that the addition of ESR1 mRNA decreases the expression of a reporter gene driven by a slightly larger (250 bp) fragment and that this effect is reversed when the ESR1 binding sequence is mutated. The relative inefficiency of this binding site in the stable transgenic line could be due either to the position of the binding site at the 3′ end of the 139-bp promoter sequence, or else to the existence of additional factors that bind to sites not included in this 139-bp fragment and contribute to repression of cxcr4b. In either case, the high levels of ESR1 provided by mRNA injection may be sufficient to bring suppression in spite of the absence of additional sequences or factors.

The existence of antagonistic interactions between CXCR4 and CXCR7 (7) has been questioned based on an analysis of ody − embryos, where the cxcr4b gene is inactivated (8). The present results establish beyond doubt that the ectopic expression of cxcr4b in the trailing region of the PLL primordium, in esr1-MO embryos, is accompanied by a complete repression of cxcr7b in this region, and that this repression is due to SDF1/CXCR4 signaling. The most obvious explanation for the difference between our previous results and those of Valentin et al. (8) would be the presence of residual CXCR4 activity in their mutant or morphant conditions either because the ody − mutation is not an amorph, or because of some compensatory mechanism, possibly involving the cxcr4a gene. CXCR4 activity is required for targeting the germ cells to the gonads (18), yet homozygous ody − adults are fertile, although at a low level, suggesting that the ody − mutation does not behave as an amorph. The cxcr4b morpholino that Valentin et al. (8) used, and the one we used previously (4), both directed against the initiation codon, have irregular effects in our hands, possibly depending on differences in genetic background. The morpholino that we used in the present study (antisplice) gives us more consistent results. Whatever the reason for previous differences in results, we believe that the present study demonstrates that CXCR4 activity can repress cxcr7b.

Based on our results, we propose a dual control for cxcr4b expression and subsequently for cxcr7b expression and primordium migration (Fig. 4). One level of control of primordium migration is the direct repression of cxcr4b by ESR1 in the trailing cells, resulting in cxcr7b expression in these cells, primordium asymmetry and directional migration. The stability of this level of control is reinforced by the positive feedback that SDF1/CXCR4 signaling exerts on cxcr4b expression. The second level of control depends on the Wnt/FGF polarization of the primordium. Wnt activity in the leading cells results in repression of cxcr7b (11) and possibly in activation of cxcr4b (as suggested by the similarity between the domains of Wnt activity/lef1 expression and the domains where cxcr4b remains expressed and cxcr7b remains repressed in the absence of CXCR4 signaling). Whether ESR1, or a cofactor, are themselves under the control of Wnt signaling, and therefore correspond to the “trailing repressor” hypothesized by Aman and Piotrowski (11), remains to be determined.

Fig. 4.

Control of expression of cxcr4b and cxcr7b in the leading (Right) and trailing (Left) regions of the migrating primordium. The expression of cxcr4b, which is homogeneous before the onset of migration (7), is repressed in the trailing third by ESR1, and maintained in the leading two-thirds by positive feedback through SDF1/CXCR4 signaling. An additional activating mechanism, possibly under direct control of Wnt signaling, ensures expression of cxcr4b in the leading cells even in the absence of CXCR4 signaling. The complementary pattern of expression for cxcr7b reflects repression by SDF1/CXCR4 signaling and an additional repression by Wnt signaling in the leading cells (11). Single lines: controls at the level of gene expression; double lines: controls at the level of gene product activity. Black and gray indicate components that are active and inactive, respectively, in the leading and trailing regions. Dotted line indicates diffusion of FGF ligands induced in the leading cells by Wnt signaling (11). Altering FGF signaling also affects cxcr4b and cxcr7b expression (12), although it is not clear whether this effect is direct or is due to changes in Wnt signaling, and this level of control has therefore not been included in this tentative diagram. Question marks indicate plausible, but undemonstrated, interactions.

The observation that ESR1 acts as a repressor of cxcr4b is intriguing, as it is well established that CXCR4 is involved in breast cancer metastasis (19). The paradoxical finding that estrogens stimulate the growth of ESR-positive breast cancer cells and at the same time significantly decrease their metastatic ability (20) would be explained if ESR1 acts as a repressor of cxcr4 in humans, as it does in zebrafish. Another estrogen receptor, ESR2b (Erβ2), plays a role in the development of the lateral line system at a later step, the formation of hair cells within the neuromasts. ESR2b is present in the cells that surround the hair cells, but not in the latter, and seems to down-regulate Notch, thereby allowing the formation of hair cells progenitor cells (21). We do not know if the implication of two estrogen receptors at different stages of lateral line development is a simple coincidence or has some historical or physiological explanation.

The control of primordium organization and migration by two self-maintained, connected systems, Wnt/FGF on one hand and CXCR4/CXCR7 on the other hand, would ensure a remarkable stability of the migration process and may explain the extreme conservation of embryonic PLL patterns across all teleosts, from the relatively basal zebrafish to highly derived flatfish embryos (22). This duality may also explain why, whereas the inactivation of SDF1, CXCR4, or CXCR7 prevents migration altogether, interfering with the other components of this control system (Wnt, FGF, ESR1) only leads to reduced migration, which eventually comes to a halt after several hours (11 –13).

Materials and Methods

Fish Strain.

All experiments were performed in the cldnb:gfp reporter line, except for the analysis of cxcr4b and cxcr7b expression in the ody − line. Both the cldnb:gfp and the homozygous ody − line were provided by D. Gilmour, EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany. Although the migration of the primordium is always altered in ody− embryos, we observed in pair matings that the severity of the phenotype (position of the primordium before it stops) varies from pair to pair. We selected for the experiments the pair that gave the highest proportion of nonmigrating primordia. Ages are expressed as hpf.

Identification of a Minimal cxcr4b Promoter.

A 6.6-kb promoter fragment, including the first exon with the ATG start codon and the first intron, was amplified by PCR using primers zCXP2 (AAGGCCTGTCACAGCTCATTGCATGTT) and zCXE2N (TTATAGCGGCCGCGTCTAAAATGATGCTCTGCAGAA), phosphorylated, digested with NotI, and inserted in a Tol-2 derived vector ahead of an ORF encoding a membrane version of mCherry (RFP) (23) and shown to drive RFP expression in the migrating primordium (GenBank accession no. Nb GU394077). Smaller fragments including the ATG of, respectively, 4.7 and 4 kb, and 600, 250 (GenBank accession no. Nb GU394078), and 139 bp (GenBank accession no. Nb GU394080) were treated in the same way and analyzed by transient transgenesis; 5 nL of a mix containing each construct (5 ng/μL) and the RNA encoding the Tol-2 transposase (5 ng/μL; synthetized from the pCS-TP plasmid with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit; Ambion) was injected at the one cell stage. Embryos were examined under fluorescence microscopy at 30–35 hpf. A Tol-2 derived vector with the 250-bp fragment harboring a mutated ESR1 binding site (250 mut), where the TGACC consensus sequence was replaced by AATAA, was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis (GenBank accession no. Nb GU394079).

Identification of Putative ESR1 Binding Sites.

The 139-bp cxcr4b minimal promoter was analyzed for binding sites of known transcriptional factors with the TESS software (http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess). This analysis revealed a composite site containing half the palindromic ESR1 binding sequence (ERE), TGACC, and a SP1 binding motif, CCCCGCCT. Such composite binding sites are found in a large number of estrogen responsive promoters (14).

esr1 Overexpression.

The ESR1 ORF was amplified from a reverse transcription of RNA extracted from 30-hpf embryos, using esr1.50 (TTACTCGAGCCACCTGCCGCCCACAAACT) and esr1.30 (AGCTCTAGAGCTTCCACAAAAACCGAGCGA) primers. The amplified fragment was digested by XhoI and XbaI and inserted in the similarly digested pCS2+ vector to yield the pCS2+zesr1 plasmid (GenBank accession no. Nb GU394081). The KpnI digested pCS2+zesr1 was used for SP6 in vitro transcription of esr1. esr1 mRNA was coinjected at a concentration of 200 ng/μL with either 250-bp-RFP or 250-mut-RFP plasmid and with Tol-2 transposase mRNA at a concentration of 25 ng/μL each. The results were analyzed with the PAST software (http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/).

Morpholino Injection.

Antisense MO were obtained from Gene Tools, diluted in water containing 5% phenol red, and injected in one-cell stage embryos. For the knockdown of esr1, a 5′UTR morpholino (5′GGAAGGTTCCTCCAGGGCTTCTCTC3′) was injected at a concentration of 0.35 mM to provide the best combination of survival (90%) and phenotype. sdf1-MO was used at a concentration of 1.25 mM instead of 0.5 mM as described previously (4). The two cxcr4b-MO oligonucleotides published previously (4, 8), both directed against the initiation ATG, gave inconsistent results in the two lines used for the present work, possibly related to differences in genetic background with the commercially available golden line used previously (4). We designed a third morpholino, cxcr4b-MO3, against the splice site, 5-TTAATCACAAGCCAACTTACATCGT-3′. When used at 3 mM, this morpholino induces low lethality (11%) and a reliable PLL phenotype. When two morpholinos were injected simultaneously, each was injected at its working concentration. The esr1 control morpholino had five mismatches: 5′GCAAGCTTCCTGCAGGCCTTCTGTC3′.

Time-Lapse Imaging.

cldnb:gfp embryos were anesthetized in 0.01% tricaine methanesulfonate (Sigma) and embedded in 0.5% agar. Time-lapse analyses were performed on an Axioimager M1 Zeiss Microscope equipped with a 20× long distance, water-immersion objective, and a CoolSnap camera. Embryos were maintained at 26 °C by a stage heating device (Pecon Gmbh), and Z stacks of 10 frames 10-μm apart, to allow for changes in focal plane due to fish development, were collected at intervals of 10 min.

Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization.

The 32-hpf embryos were processed for in situ hybridization as described by Westerfield (24). The hybridized probe was detected using an alkaline phosphatase-coupled antidioxygenin antibody (1:2,000; Roche). The esr1 probe was prepared as follows: the primers AGAATCGAGTGCCGCTGTAT and GAGGAAATCAGAGCAGCGTT were used to amplify part of the 3′ untranslated region of the esr1 cDNA. The PCR product was cloned in the pZERO-2 vector (Invitrogen) and used as a template to generate the RNA probes. Both antisense and sense digoxygenin-labeled probes were synthesized using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase (Roche), respectively, and purified with a RNA purification kit (Macherey-Nagel). The sense probe showed no specific labeling. We also used digoxygenin-labeled riboprobes for the detection of cxcr4b and cxcr7b (7), and of lef1 (25). The esr1 probe was used at a concentration of 150–200 ng/500 μL, the other probes were used at 500 ng/500 μL. Stained embryos were mounted in 100% glycerol and photographed on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a Canon G5 camera.

Combined in Situ Hybridization and Immunolabeling.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization used a rhodamine-coupled antidioxygenin antibody (1:2,000; Boehringer Mannheim). GFP was revealed with rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000; Invitrogen), followed by anti-rabbit Alexa488-coupled secondary antibody (1:200; Molecular Probes). In nonfluorescent in situ hybridization/immunolabeling experiments, in situ hybridization was revealed by alkaline phosphatase-coupled antidioxygenin antibody (1:2,000; Roche), giving a blue precipitate, and GFP was revealed by rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000; Invitrogen), followed by anti-rabbit HRP-coupled secondary antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch), forming a brown precipitate. Fluorescent embryos were examined with a Leica TSP confocal microscope; nonfluorescent embryos were mounted in 100% glycerol and photographed on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a Canon G5 camera. The domain of expression of cxcr7b was considered to be markedly expanded when it extended beyond the posterior half of the primordium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Raible for suggesting significant improvements to an earlier version of this paper, D. Gilmour for the gift of the cldnb:gfp reporter and ody− mutant lines, K. Kawakami for the gift of the Tol-2 system, T. Piotrowski for comments on the manuscript, N. König for help with the statistical analysis, T. Maudelonde for bringing to our attention the paper by Garcia et al. (20), and the Montpellier RIO Imaging technical facility for the use of confocal microscope. This work was supported by Institut National pour la Santé et la Recherche Médicale, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and Agence Nationale pour la Recherche contracts Neurogen and zebravirus. L.G. was supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. GU394077, GU394078, GU394079, GU394080, and GU394081).

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0909998107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudière C. The lateral line microcosmos. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2118–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.1568407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalfe WK. Sensory neuron growth cones comigrate with posterior lateral line primordial cells in zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:218–224. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gompel N, et al. Pattern formation in the lateral line of zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2001;105:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David NB, et al. Molecular basis of cell migration in the fish lateral line: Role of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and of its ligand, SDF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16297–16302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252339399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q, Shirabe K, Kuwada JY. Chemokine signaling regulates sensory cell migration in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2004;269:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas P, Gilmour D. Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line. Dev Cell. 2006;10:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dambly-Chaudière C, Cubedo N, Ghysen A. Control of cell migration in the development of the posterior lateral line: Antagonistic interactions between the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7/RDC1. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boldajipour B, et al. Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration. Cell. 2008;132:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cubedo N, Cerdan E, Sapède D, Rossel M. CXCR4 and CXCR7 cooperate during tangential migration of facial motoneurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aman A, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Dev Cell. 2008;15:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nechiporuk A, Raible DW. FGF-dependent mechanosensory organ patterning in zebrafish. Science. 2008;320:1774–1777. doi: 10.1126/science.1156547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecaudey V, Cakan-Akdogan G, Norton WHJ, Gilmour D. Dynamic Fgf signaling couples morphogenesis and migration in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development. 2008;135:2695–2705. doi: 10.1242/dev.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez R, Nguyen D, Rocha W, White JH, Mader S. Diversity in the mechanisms of gene regulation by estrogen receptors. Bioessays. 2002;24:244–254. doi: 10.1002/bies.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegner SA, et al. Genomic organization and functional characterization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, a major entry co-receptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4754–4760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chong SW, Emelyanov A, Gong Z, Korzh V. Expression pattern of two zebrafish genes, cxcr4a and cxcr4b . Mech Dev. 2001;109:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knaut H, Werz C, Geisler R, Nüsslein-Volhard C, Tübingen 2000 Screen Consortium A zebrafish homologue of the chemokine receptor Cxcr4 is a germ-cell guidance receptor. Nature. 2003;421:279–282. doi: 10.1038/nature01338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doitsidou M, et al. Guidance of primordial germ cell migration by the chemokine SDF-1. Cell. 2002;111:647–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller A, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia M, Derocq D, Freiss G, Rochefort H. Activation of estrogen receptor transfected into a receptor-negative breast cancer cell line decreases the metastatic and invasive potential of the cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11538–11542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Froehlicher M, et al. Estrogen receptor subtype beta2 is involved in neuromast development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Dev Biol. 2009;330:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pichon F, Ghysen A. Evolution of posterior lateral line development in fish and amphibians. Evol Dev. 2004;3:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2004.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaner NC, et al. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westerfield M. The zebrafish book. Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorsky RI, Itoh M, Moon RT, Chitnis A. Two tcf3 genes cooperate to pattern the zebrafish brain. Development. 2003;130:1937–1947. doi: 10.1242/dev.00402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriuchi M, Moriuchi H, Turner W, Fauci AS. Cloning and analysis of the promoter region of CXCR4, a coreceptor for HIV-1 entry. J Immunol. 1997;159:4322–4329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.