Abstract

Kinesin is a two-headed motor protein that powers organelle transport along microtubules1. Many ATP molecules are hydrolysed by kinesin for each diffusional encounter with the microtubule2,3. Here we report the development of a new assay in which the processive movement of individual fluorescently labelled kinesin molecules along a microtubule can be visualized directly; this observation is achieved by low-background total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy4 in the absence of attachment of the motor to a cargo (for example, an organelle or bead). The average distance travelled after a binding encounter with a microtubule is 600 nm, which reflects a ~ 1% probability of detachment per mechanical cycle. Surprisingly, processive movement could still be observed at salt concentrations as high as 0.3 M NaCl. Truncated kinesin molecules having only a single motor domain do not show detectable processive movement, which is consistent with a model in which kinesin’s two force-generating heads operate by a hand-over-hand mechanism.

Kinesin is composed of two heavy chains, each consisting of a 340-amino-acid, N-terminal force-generating domain, a long α-helical coiled coil interrupted in the middle by a proline–glycine-rich hinge, and a small globular C-terminal domain that interacts with light chains5,6. To add a fluorescent label to kinesin in a manner that does not interfere with motor function, the ubiquitous human kinesin gene7 was truncated just before the hinge at amino-acid residue 560 and a short peptide containing a reactive cysteine8 was introduced at the C terminus (uhK560cys). uhK560cys was expressed in bacteria, purified, and reacted at its C-terminal cysteine with a maleimide-Cy3 fluorescent dye (Fig. 1 legend).

FIG. 1.

Movement of a single fluorescently labelled kinesin molecule along an axoneme. a, Kinesin (uhK560cys) labelled at the C-terminal cysteine residue with Cy3 fluorescent dye was combined with Cy5-labelled axonemes in the presence of ATP. The specimen was illuminated by the evanescent field resulting from total internal reflection of a laser beam at the boundary between the fused silica slide and the aqueous solution4. b, Cy5-axoneme. c, uhK560-Cy3. The caret (^) marks a stationary fluorescent spot, and the arrows track a moving fluorescence spot (time in seconds). Other spots visible in individual panels are ones that associated briefly (< 2 s) with the axoneme. Bar, 5 µm.

METHODS. uhK560 with an additional C-terminal peptide containing a reactive cysteine (PSIVHRKCF)8 was expressed in Escherichia coli21 and purified by phosphocellulose followed by mono-Q chromatography. uhK560-Cy3 (concentration determined from absorbance at 280 nm, A280; ref. 22) was labelled to a stoichiometry of 0.1 to 0.5 dyes per polypeptide chain as described4. The uhK560-Cy3 preparation was centrifuged at 100,000 r.p.m. for 10 min in a table-top ultracentrifuge to remove any aggregates; additional microtubule-affinity purification19 was sometimes performed to improve motility. Analysis of low concentrations of uhK560-Cy3 by sucrose gradient velocity sedimentation16 (5 S) and Superose-6 gel filtration chromatography indicates that it is dimeric. The concentrations used in the sucrose gradient (5 nM) suggest that uhK560-Cy3 remains dimerized under the conditions of the assay. The microtubule-stimulated ATPase23 properties of uhK560 labelled with Cy3 at a 0.43 molar ratio of dye to polypeptide (kcat = 22.2 ± 1.0 s−1/site; K0.5,MT = 1.1 ± 0.2 µM) and at 0.96 stoichiometry (kcat = 19.2 ± 0.2 s−1/site; K0.5,MT = 1.6 ± 0.06 µM) were similar to that of the unlabelled protein (kcat = 25.8 ± 0.8 s−1/site; K0.5,MT = 0.7 ± 0.08 µM) (measured in the motility buffer: 12 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA). Cy5-labelled axonemes24 were combined with 0.5–1.5 nM uhK560-Cy3 in motility buffer containing 1 mM ATP, 7.5 mg ml−1 BSA, 0.5% mercaptoethanol and an oxygen scavenger system20 at 25 °C. BSA inhibited nonspecific adsorption of kinesin but did not prevent axonemes from attaching to the slide. Details of low-background total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy are described elsewhere4. In these experiments, 5.8 ± 1.0 association events per min per µm axoneme (n = 8 axonemes; 5-min observation for each axoneme) were observed when the uhK560-Cy3 concentration was 0.6 nM, whereas only 0.05 ± 0.01 events per min were scored on glass without an axoneme. Kinesin spots moving on an axoneme disappeared at 0.42 ± 0.03 s−1, which was significantly faster than the rate of photobleaching of glass-attached kinesin (0.02 ± 0.0005 s−1).

When uhK560-Cy3 (0.6 nM) was combined with 1 mM ATP and Cy5-labelled flagellar axonemes, fluorescent kinesin molecules could be seen binding to and moving unidirectionally along axonemal microtubules (Fig. 1). The velocity of movement was 300 ± 70 nm s−1 (mean ± s.d.; n = 60), which was similar to the gliding velocity of axonemes on uhK560-Cy3-coated glass surfaces (370 ± 40 nm s−1; n = 28).

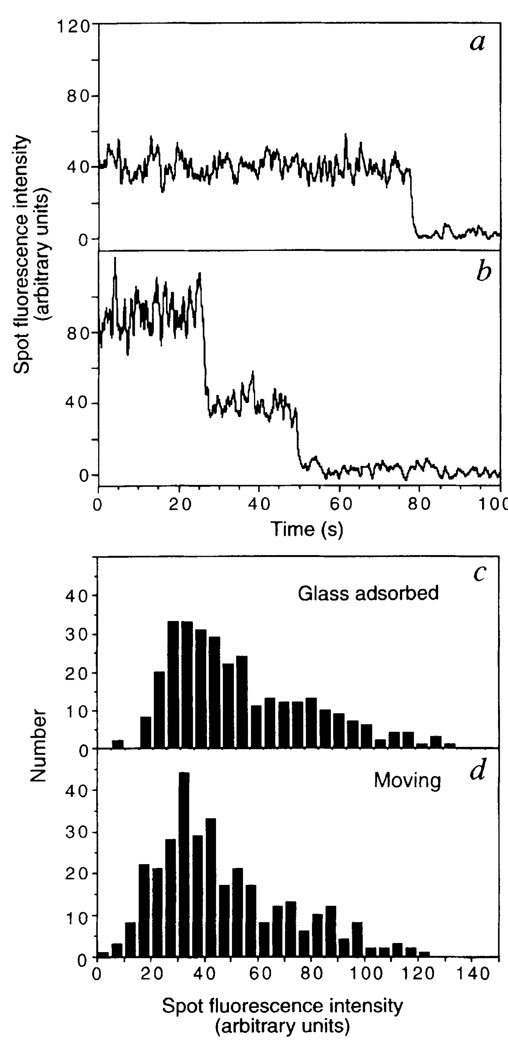

To verify that the translocating objects were single kinesin molecules, the photobleaching characteristics and intensities of fluorescent spots were examined. The fluorescence of surface-adsorbed kinesin disappeared primarily in either a one-step (Fig. 2a) or a two-step process (Fig. 2b), as expected for photobleaching reactions of one or two dye molecules, respectively, bound to the uhK560cys dimer. The percentage of one-step, two-step, three-step and more-than-three-step photobleaching events was 74, 25, 2 and 0%, respectively (n = 355). Assuming labelling of only the C-terminal cysteine and random dimerization of two chains, these values agree with the percentages expected of single-dye (72.6%) and double-dye (27.4%) labelled kinesin molecules predicted from the labelling stoichiometry (0.43 dye/polypeptide). The fluorescence intensities of kinesin molecules randomly adsorbed onto a glass slide (Fig. 2c) were also similar to those of moving spots (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these results are consistent with the idea that single kinesin molecules can move along microtubules.

FIG. 2.

Photobleaching properties and fluorescence intensities of fluorescently labelled kinesin. uhK560-Cy3 was adsorbed onto a fused-silica slide, and the intensities of individual fluorescent spots plotted against time. Typical examples of one-step (a) or two-step (b) photobleaching events are shown, reflecting one or two Cy3 dye molecules attached to kinesin, respectively. The distribution of the fluorescence intensities of isolated uhK560-Cy3 spots adsorbed onto the slide (c) or moving along the axoneme (d) are comparable, which suggests that moving fluorescent spots are single molecules and not higher-order aggregates. Intensities were measured using a rolling 8-frame average to reduce fluctuations, summing intensities from a 7 × 7 pixel window, and subtracting the background intensity from an adjacent region on the slide. The intensities of two dye molecules (b) and three dye molecules (not shown) are in the linear range of the camera, as photobleaching caused approximately equal decreases in intensity.

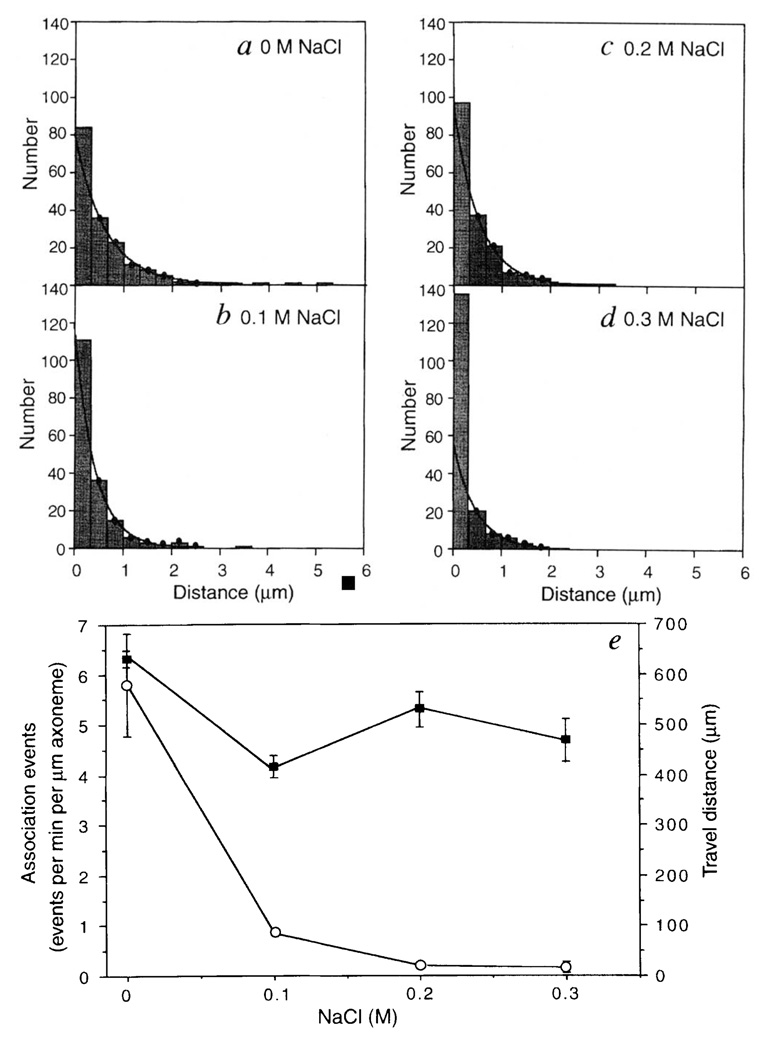

The distance travelled by single kinesin molecules was distributed exponentially (Fig. 3a), as described for bead motility assays9. Based upon the mean travel distance of 630 ± 30 nm and an 8-nm step per cycle for kinesin10, the probability of remaining bound to the microtubule per mechanical cycle is ~ 99% (e(−8/630)). If one ATP is hydrolysed per 8-nm step (which is consistent with uhK560 ATPase rates), then 40 ATP molecules on average would be hydrolysed by each kinesin motor domain per diffusional encounter with the microtubule, which is intermediate between two previous estimates2,3.

FIG. 3.

Effects of ionic strength on the travel distance and association frequencies of uhK560-Cy3. The distances travelled by single uhK560-Cy3 molecules in motility buffer containing 0 M (a), 0.1 M (b), 0.2 M (c) or 0.3 M NaCl (d) are shown. The dots indicate the bins that were used for exponential fitting. In e, the travel distances (filled squares) in a–d are compared with that of uhK560-Cy3 association events with the axoneme (open circles). Mean and standard deviations of association events were scored from 5–12 different axonemes (5–40 associations per axoneme). The velocities of uhK560–Cy3 that travelled for > 0.5 µm were 300 ± 60, 380 ± 120, 310 ± 80 and 250 ± 60 nm s−1 at 0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 M NaCl, respectively (n = 60, 41, 52 and 20).

METHODS. Measurements of solitary uhK560-Cy3 molecules were made by tracking fluorescent spots that were positioned over the axoneme for at least 5 video frames. Static associations of > 3 s were rare, and were excluded as they probably represented nonspecific associations. Although travel distances of < 0.3 µm could not be measured accurately, all measurable associations, including those with < 0.3 µm translocations, are included in these histograms. As the first bin may contain nonspecific associations with the axoneme, it was excluded from the two-parameter exponential fits. The means determined from the decay constants (630, 415, 520 and 470 nm at 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 M NaCl, respectively) were in general agreement with the distribution averages (620, 430, 500 and 300 nm).

The effect of ionic strength on single kinesin molecule motility is shown in Fig. 3. Although the number of measurable associations events decreased dramatically with increasing salt concentration, the average travel distance and velocity (Fig. 3 legend) of kinesin molecules that had initiated movement were much less affected. The number of ATP molecules hydrolysed per microtubule encounter, however, was reported to decrease 10-fold when salt was raised from 0.05 to 0.15 M (ref. 3). This apparent discrepancy may reflect a difference between bulk ATPase measurement and observation of single molecule behaviour in a microscopic assay. At higher salt, kinesin may undergo transient microtubule interactions (too fast to be detected in our assay) that result in ATP hydrolysis or product release, but not processive movement. Once kinesin is bound in a manner that allows processive movement to begin, then the travel distance appears to be only modestly affected by ionic strength.

The mechanism by which kinesin moves for long distances on a microtubule without dissociating remains unresolved, although it has been suggested that the two heads of kinesin may operate in a hand-over-hand manner3,11–13. To explore this idea, we prepared a series of truncated, monomeric Drosophila kinesin proteins12,14,15, as well as a longer kinesin molecule (dK440) that forms a dimer15,16 (Table 1). Consistent with previous studies12,17, even the monomeric motors generated movement in a gliding assay in which many motors interact simultaneously with the microtubule, although the velocity of dK340 was very slow. In the single-molecule fluorescence motility assay, dK440-Cy3 molecules moved along microtubules with a velocity and travel distance comparable to that described for uhK560-Cy3. In contrast to observations for dK440-Cy3, unidirectional movement by dK340-Cy3, dK350-Cy3 or dK365-Cy3 was not observed. Furthermore, association–dissociation reactions of these monomeric kinesins with the axoneme were seen less frequently than for dK440, suggesting that their association–dissociation cycle may be faster than can be detected by video analysis.

TABLE 1.

Motility of monomeric and dimeric kinesin

| Microtubule gliding |

Single molecule fluorescence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin | Velocity (nm s−1) |

Velocity (nm s−1) |

Travel distance (nm) |

Association events (events per min per µm MT) |

| dK340 | 7 ± 2 | – | – | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| dK350 | 120 ± 10 | – | – | 0.22 ± 0.07 |

| dK365 | 110 ± 10 | – | – | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| dK440 | 570 ± 70 | 340 ± 90 | 400 ± 40 | 2.48 ± 0.40 |

Microtubule translocation induced by monomeric and dimeric Drosophila kinesin proteins (number of amino acids indicated) in multiple motor gliding or single fluorescent molecule motility assays. Velocities are the means and s.d. of > 20 measurements (microtubules in the case of the gliding assay, and axonemes in the case of the single molecule fluorescence assay), and the association events are the means and s.d. from > 3 axonemes (5–20 min of observation per axoneme (a minimum of 10 events were scored)). The dK440 travel distance and error were determined as shown in Fig. 3. Dashes signify that no movement was detected. dK340cys, dK350cys, dK365cys, and dK440cys were generated by polymerase chain reaction using the Drosophila kinesin gene, expressed in bacteria and purified by phosphocellulose followed by mono-Q chromatography. Hydrodynamic studies indicated that, consistent with previous work12,14,15, dK440 is a dimer and that dK365, dK350 and dK340 are monomers. Sucrose gradient velocity sedimentation indicates that dK440-Cy3 (5 S) remains a dimer at 3 nM. For microtubule gliding assays, the kinesin reactive cysteine was modified with long-chain biotin–maleimide8, streptavidin was added in an 8:1 ratio, and the kinesin–biotin–streptavidin complexes were isolated by microtubule affinity18,19. For the motility assay, 0.5 mg ml−1 biotinylated BSA was introduced into a microscopic flow chamber. After washing, streptavidin-modified kinesin motor (1–5 µM) was introduced in motility buffer with 3 mg ml−1 casein. Next, rhodamine-labelled microtubules18 (~10 µg ml−1) were introduced in the above buffer with 1 mM ATP and an oxygen scavenger system20 and examined by fluorescence microscopy. For the single molecule fluorescence assay, Drosophila kinesin proteins were labelled with Cy3 and assayed for motility as described for Fig. 1.

In conclusion, these results provide definitive evidence for the ability of a single kinesin molecule at physiological ionic strength to move along a microtubule even in the absence of attachment to a cargo. The travel distance reported here is only slightly lower than that of kinesin moving a bead of diameter 0.2 µm (1.4 µm)9, which probably reflects the smaller diffusion coefficient of a bead compared with a protein. Furthermore, kinesin molecules containing a single motor domain showed no detectable processive movement, although higher spatial resolution techniques10 will determine whether they undergo very short movements. In any event, these results and others12 argue that two kinesin force-generating heads are required for long-distance movements along a microtubule. Assays similar to those described here could be applied to other processive enzymes such as polymerases and helicases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH. We thank C. McGee for discussion, T. Yagi for preparation of axonemes, N. Hom-Booher for technical assistance and C. Coppin and R. Cooke for comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bloom G, Endow S. Motor Proteins 1: Kinesin. London: Academic; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hackney DD. Nature. 1995;377:448–450. doi: 10.1038/377448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert SP, Webb MR, Brune M, Johnson KA. Nature. 1995;373:671–676. doi: 10.1038/373671a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funatsu T, Harada Y, Tokunaga M, Saito K, Yanagida T. Nature. 1995;374:555–559. doi: 10.1038/374555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JT, Laymon RA, Goldstein LS. Cell. 1989;56:879–889. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirokawa N, et al. Cell. 1989;56:867–878. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navone F, et al. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:1263–1275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itakura S, et al. Biochem. biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;196:1504–1510. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Block SM, Goldstein LS, Schnapp BJ. Nature. 1990;348:348–352. doi: 10.1038/348348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svoboda K, Schmidt CF, Schnapp BJ, Block SM. Nature. 1993;365:721–727. doi: 10.1038/365721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hackney DD. Proc. natn. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:6865–6869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berliner E, Young EC, Anderson K, Mahtani H, Gelles J. Nature. 1995;373:718–721. doi: 10.1038/373718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnapp BJ, Crise B, Sheetz MP, Reese TS, Kahn S. Proc. natn. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:10053–10057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang T, Hackney DD. J. biol. Chem. 1994;269:16493–16501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correia JJ, Gilbert SP, Moyer ML, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4898–4907. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang T, Suhan J, Hackney DD. J. biol. Chem. 1994;269:16502–16507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart RJ, Thaler JP, Goldstein LS. Proc. natn. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:5209–5213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyman A, et al. Meth. Enzym. 1990;196:303–319. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Cell. 1985;41:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harada Y, Sakurada K, Aoki T, Thomas DD, Yanagida T. J. molec. Biol. 1990;216:49–68. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu T, et al. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13259–13266. doi: 10.1021/bi00040a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert SP, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4677–4684. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vale RD, Coppin CM, Malik F, Kull FJ, Milligan RA. J. biol. Chem. 1994;269:23769–23775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamiya R, Kurimoto E, Muto E. J. Cell Biol. 1991;112:441–447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.3.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]